by DGR News Service | Aug 8, 2020 | Climate Change, Human Supremacy, The Problem: Civilization

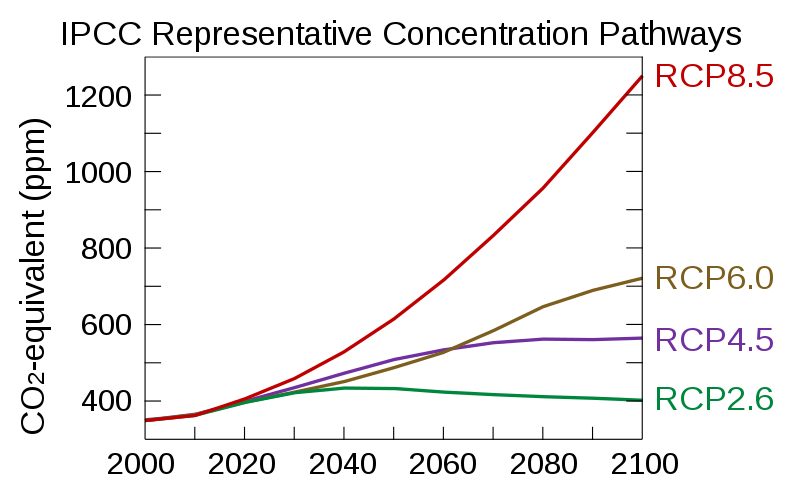

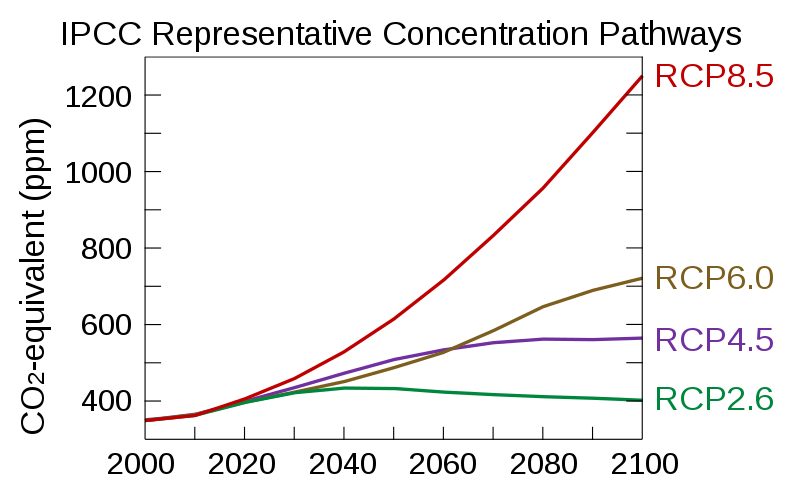

This article, originally posted by the Woods Hole Research Centre on August 3rd 2020, states that the “Worst case” for CO2 emissions scenario is actually the best match for assessing the climate risk, impact by 2050.

The RCP 8.5 CO2 emissions pathway, long considered a “worst case scenario” by the international science community, is the most appropriate for conducting assessments of climate change impacts by 2050, according to a new article published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The work was authored by Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC) Risk Program Director Dr. Christopher Schwalm, Dr. Spencer Glendon, a Senior Fellow at WHRC and founder of Probable Futures, and by WHRC President Dr. Philip Duffy.

Long dismissed as alarmist or misleading, the paper argues that is actually the closest approximation of both historical emissions and anticipated outcomes of current global climate policies, tracking within 1% of actual emissions. “Not only are the emissions consistent with RCP 8.5 in close agreement with historical total cumulative CO2 emissions (within 1%), but RCP8.5 is also the best match out to mid-century under current and stated policies with still highly plausible levels of CO2 emissions in 2100,” the authors wrote. “…Not using RCP8.5 to describe the previous 15 years assumes a level of mitigation that did not occur, thereby skewing subsequent assessments by lessening the severity of warming and associated physical climate risk.”

Four scenarios known as Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) were developed in 2005 for the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Report (AR5). The RCP scenarios are used in global climate models, and include historical greenhouse gas emissions until 2005, and projected emissions subsequently. RCP 8.5 assumes the greatest fossil fuel use, and a resulting additional 8.5 watts per square meter of radiative forcing by 2100. The commentary also emphasizes that while there are signs of progress on bending the global emissions curve and that our emissions picture may change significantly by 2100, focusing on the unknowable, distant future may distort the current debate on these issues. “For purposes of informing societal decisions, shorter time horizons are highly relevant, and it is important to have scenarios which are useful on those horizons. Looking at mid-century and sooner, RCP8.5 is clearly the most useful choice,” they wrote.The article also notes that RCP 8.5 would not be significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, adding that “we note that the usefulness of RCP 8.5 is not changed due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Assuming pandemic restrictions remain in place until the end of 2020 would entail a reduction in emissions of -4.7 Gt CO2. This represents less than 1% of total cumulative CO2 emissions since 2005 for all RCPs and observations.”

“Given the agreement of 2005-2020 historical and RCP8.5 total CO2 emissions and the congruence between current policies and RCP8.5 emission levels to mid-century, RCP8.5 has continued utility, both as an instrument to explore mean outcomes as well as risk,” they concluded. “Indeed, if RCP8.5 did not exist, we’d have to create it.”

You can access the original article here:

https://whrc.org/worst-case-co2-emissions-scenario-is-best-match-for-assessing-climate-risk-impact-by-2050/

Featured image: Efbrazil / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

by DGR News Service | Jun 26, 2019 | Climate Change

by Kollibri terre Sonnenblume / Macska Moksha Press, republished with permission

A June 15th headline elicited feelings in me of both shock and déjà vu: “Climate change: Arctic permafrost now melting at levels not expected until 2090” [Independent, June 15, 2019]. Shock because that’s quite a bit ahead of time. Déjà vu because how often does a climate change headline or story use a phrase like that? “At levels not expected until” or “faster than expected” or “sooner than predicted”? I opened a search engine and started plugging in these and other variants to find out. It didn’t take long to answer my question: regularly, as it turns out.

Here are a few examples, from 2014 to the present [all emphasis is mine]:

- “As the Climate Council has reported, hot days have doubled in Australia over the past half-century. During the decade from 2000 to 2009, heatwaves reached levels not expected until the 2030s. The anticipated impacts from climate change are arriving more than two decades ahead of schedule.” [“‘It’s been hot before’: faulty logic skews the climate debate,” The Conversation, February 20, 2014]

- “Climate change will reduce crop yields sooner than thought” (University of Leeds study) [Science Daily, March 16, 2014]

- “New research shows climate change will reduce crop yields sooner than expected” (different study) [Arizona State University, March 25, 2014]

- “Dangerous global warming will happen sooner than thought – study: Australian researchers say a global tracker monitoring energy use per person points to 2C warming by 2030″ [The Guardian, 9 March 2016]

- “Scientists Warn Drastic Climate Impacts Coming Much Sooner Than Expected: Former NASA scientist James Hansen argues the new study requires much faster action reducing greenhouse gases.” [Inside Climate News, Mar 22, 2016]

- “Florida Reefs Are Dissolving Much Sooner Than Expected” [ClimateCentral, May 3, 2016]

- “Scientists caught off-guard by record temperatures linked to climate change:” “We predicted moderate warmth for 2016, but nothing like the temperature rises we’ve seen” [Thomson Reuters Foundation, July 26, 2016]

- “Ice-free Arctic may happen much sooner than predicted so far: study” [DownToEarth, 16 August 2018]

- “Ground that is not freezing in the Arctic winter could be a sign the region is warming faster than believed” [“Scientists surprised to find some Arctic soil may not be freezing at all even in winter,” CNBC, Aug 22 2018]

- “Paris global warming targets could be exceeded sooner than expected because of melting permafrost, study finds” [Independent, 17 September 2018]

- “Climate change impacts worse than expected, global report warns” [National Geographic, October 7, 2018]

- “Ocean Warming is Accelerating Faster Than Thought, New Research Finds” [NY Times, Jan 10th, 2019]

- “Scientists warn climate change could reach a ‘tipping point’ sooner than predicted as global emissions outpace Earth’s ability to soak up carbon” [Daily Mail, 23 January 2019]

- “Scientists who study the northern Bering Sea say they’re seeing changed ocean conditions that were projected by climate models – but not until 2050.” [“Bering Sea changes startle scientists, worry residents,” AP, Apr 13, 2019]

- “New Climate Report Suggests NYC Could Be Under Water Sooner Than Predicted” [Gothamist, May 21, 2019]

- “Antarctic Ice Sheet Is Melting Way Faster Than Expected, Scientists Warn” [Huffington Post, 06/14/2018]

- “Arctic Permafrost Melting 70 Years Sooner Than Expected, Study Finds” (The original source for the Independent article) [Weather.com, June 14th, 2019]

So why does this keep happening? There are several reasons:

#1: IPCC as standard-setter

In the contrast between reality and predictions, the conventional baseline for predictions is set by the IPCC, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. For governments, NGOs and media, the IPCC reports are the institutional yardstick.

However, the bureaucratic process that produces IPCC reports is not exclusively scientific. Final documents are created by consensus among all the participants, some of whom are policy-makers without scientific backgrounds or knowledge. Political concerns come into play, such as how the recommendations will affect their home industries and what kind of story they’re trying to sell to their populace. Additionally, because this process is slow, the data is not current. When an IPCC report is released, the numbers in it are often at least five years old.

In describing how the IPCC operates, Meteorologist Nick Humphrey said: “Essentially making sure it’s not too dire [and] shows economic paths to success.” Clearly, such methodology has been giving us a picture that underestimates the true situation, and that is not in anybody’s interest.

#2: The Situation is Complex

Though the over-arching term is “global warming,” the situation isn’t as simple as consistently increasing temperatures in all areas all the time. For example, a warming Arctic has destabilized the jet stream, and in some cases this has sent polar air south, chilling regions to below their normal ranges. Such local cold snaps are not the proof that global warming isn’t real, as some claim when they happen, but rather a demonstration of how real it is.

Further, multiple feedback loops are in effect which are not fully understood or easily predictable individually, let alone in the aggregate. For example, less ice in the Arctic Sea leads to more heat being absorbed by the ocean (since open water is darker in color than ice), which in turn leads to higher temperatures. Higher temperatures in the region lead to more permafrost thawing, which releases methane into the atmosphere, increasing temperatures further. Which leads to more ice melting… (For more, see Dahr Jamail’s “How Feedback Loops Are Driving Runaway Climate Change.”)

Those are only two of many, many factors—all interrelated in ways we don’t understand—that all have their own “tipping points,” which are events when runaway change strikes, leading to rapid transformations. We have yet to experience one of those in modern times, but paleoclimatologists have found evidence of these events in the past. (The last such period, the Younger Dryas—12,900 to 11,700 years ago—corresponds to the rise of agriculture in the Mideast, which—ironically—established both civilization and ecocide, leading us directly to our sorry situation today.)

A little-discussed and poorly-understood factor in all these trends is climate sensitivity, and the difference between short and long term sensitivity. For a brief explanation, I quote Peter Wadhams, Professor of Ocean Physics, and Head of the Polar Ocean Physics Group in the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge, who commented:

“There is a big difference between the short term sensitivity, which is used to calculate warming over a few years, and the long term sensitivity which represents how much warming the earth is going to be subjected to if you don’t add more CO2 but let the effects of the present levels work their way fully through the climate system. Short term sensitivity is 2-4.5 C, but long term is more like 10C. The crime of IPCC and other modelling outfits is that they are aware of this difference between short and long term, but still use the short term value even when they are doing hand-waving studies of what is going to happen over the next century or two.”

#3: Lack of Big Picture Perspective

“Climate change is an interdisciplinary problem,” is how Humphrey puts it. “Marine biologists, conservation biologists, sociologists, political scientists, geologists, meteorologists, glaciologists, etc, really fill the gap where the climate scientists do not go because it simply isn’t their specialization or have the time to go in their research.”

The increasing specialization of the sciences and the isolation of its many branches from each other is a trend that has been happening for over a century, and has become extreme at this point. There is a tendency not merely to miss the forest for the trees, but the trees for the leaves.

In order to fully comprehend, accurately predict, and rationally respond to our situation, we must look at the big picture—how the leaves make up the forest—but very few people are doing that. This is a job for generalists capable of integrating seemingly disparate but—in actuality—intimately connected threads, and of clearly conveying what they see. However, neither academia nor the employing world encourage generalists at this time; quite the opposite, in fact. Virtually the only way to find your place and make your way in the sciences is by establishing a niche. This is not serving us.

#4: No Money for Predicting Undesirable Outcomes

Researchers require resources to do their thing, which nearly 100% of the time entails pleasing an institution, whether that’s an employer or a grantor. Such funders have their own agendas, and few (if any) are interested in hearing about unhappy endings.

#5: Scientists Hit the Hopium Pipe Too

Finally, scientists are products of our culture just like everybody else, and our culture is primarily one of denial, whether that’s about the reality of our past (genocide and slavery) or our present (brutal military and economic hegemony, inverted fascism). Most scientists not only don’t want to deliver a dire message, but they don’t want to believe it themselves either, even if that’s what their findings show. This is understandable on a personal level. Scientifically, though, it is fundamentally dishonest.

Okay, so then what?

It’s increasingly clear that our situation is worse than we’ve been told, perhaps far, far worse. One can choose to scoff at those predicting drastic outcomes like near-term human extinction, but how does one support that kind of skepticism when “reasonable” projections have so far proven to be woeful underestimates?

But when it comes to making accurate predictions, maybe it’s no longer important. Perhaps the lesson here is just that it’s worse than we think and worse than we want and—we must consider this possibility—worse than we can fix. So then our challenge is to accept that and to take responsible action.

If you hit someone on the road, the responsible action is to go back and see how s/he is. It’s fair to describe US culture as a high speed vehicle striking one innocent creature after another without ever looking back, individually or collectively. This is untenable in a host of ways, and always has been.

Acting with malice takes a toll on both perpetrator and victim. In our case, the victim is the planet and she’s turning the tables on us, on her own schedule, whether we see it coming or not. Heads up!

—

Kollibri terre Sonnenblume is a writer, photographer, tree hugger, animal lover, and dissident. Kollibri’s past experiences include urban bike farmer, Indymedia activist, and music critic. Kollibri holds a BA in “Writing Fiction & Non-fiction” from the St. Olaf Paracollege in Northfield, Minnesota.

Follow Kollibri at: Facebook | Instagram

—

Editor’s Note: this is why we believe the DEW strategy is fully justified, and, perhaps, our only hope.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 4, 2018 | Lobbying

Spokane Judge Allows Necessity Defense; Washington State Appeals

Spokane – On March 8, Spokane District Court Judge Debra Hayes issued an order allowing for the necessity defense in a jury trial scheduled to start April 23, 2018, involving a climate change protestor’s alleged delay of oil and coal trains in September 2016. On March 30, the Spokane County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office appealed Judge Hayes’ ruling.

In September 2016, the Reverend George Taylor joined with fellow Veterans for Peace members to block coal and oil trains from passing through Spokane. Their action followed a similar action by the local Raging Grannies. All six protestors were charged with trespass and obstructing a train; five pled guilty for various reasons. Rev. Taylor chose to go forward to trial, and filed a motion asking the judge to allow him to present a “necessity defense,” i.e., that he committed one harm (trespass and blocking a train) to prevent greater harms (climate change and risks of oil train derailments).

After hearings on June 26 and August 21, 2017, Judge Hayes ruled that Taylor may present the necessity defense to the jury to justify his alleged civil disobedience. She noted, “Civil resistance is breaking a law to uphold a higher law when the threat is imminent and every legal means has not resulted in policy change.” (Order at p. 8).

“Climate change is real, and neither government nor industry is taking appropriate action to address it. Citizens therefore must bring their own voices and actions to bear to try to stop destruction of the planet,” said defendant Rev. George Taylor.

In this case, the necessity defense is based on two distinct environmental dangers to the Spokane area posed by transport of fossil fuels by train.

- First, the incineration of rail-transported coal and oil will contribute to climate change, which poses existential threats to the planet and all species, as soaring temperatures cause extreme weather patterns, disrupt ecosystems, and alter and destroy basic resources necessary for human life, including water availability and agricultural production.

- Second, rail transport of Bakken crude oil is extraordinarily dangerous as demonstrated by oil train derailments and explosions throughout North America, including at Mosier, Oregon on June 3, 2016.

Judge Hayes’ necessity order was supported by testimony of two experts: Dr. Steve Running, Professor of Global Ecology at the University of Montana and co-author of the 4th IPCC Report on Climate Change for which he shared the Nobel Peace Prize, and Prof. Tom Hastings, Assistant Professor of Conflict Resolution at Portland State University, and author of several books on civil resistance, including A New Era of Nonviolence (McFarland 2014).

Judge Hayes’ necessity order made numerous findings, including:

- The failure to act more forcefully to abate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will lead to harms that are severe, imminent, and irreparable, both at a global level and regionally in the Inland Northwest (Order at p.6);

- Civil resistance can be effective in bringing about social change; historic victories such as de-segregation and women’s suffrage have resulted from civil resistance and the same result could be accomplished for environmental protections, resulting in institutional, corporate and public policy changes (Order at p. 7); and

- When all other legal means have been taken, and those attempts have not resulted in change, the judicial branch is the last, best hope. (Order at p. 8).

“The judge nailed the problem: climate change is already causing adverse harms to the Inland Northwest ecosystems, which will in turn hurt people. And these harms will worsen. She found that it is reasonable to allow a jury to decide whether these harms outweigh George Taylor’s resistance actions for which he has been charged criminally,” said Rachael Paschal Osborn, Taylor’s attorney.

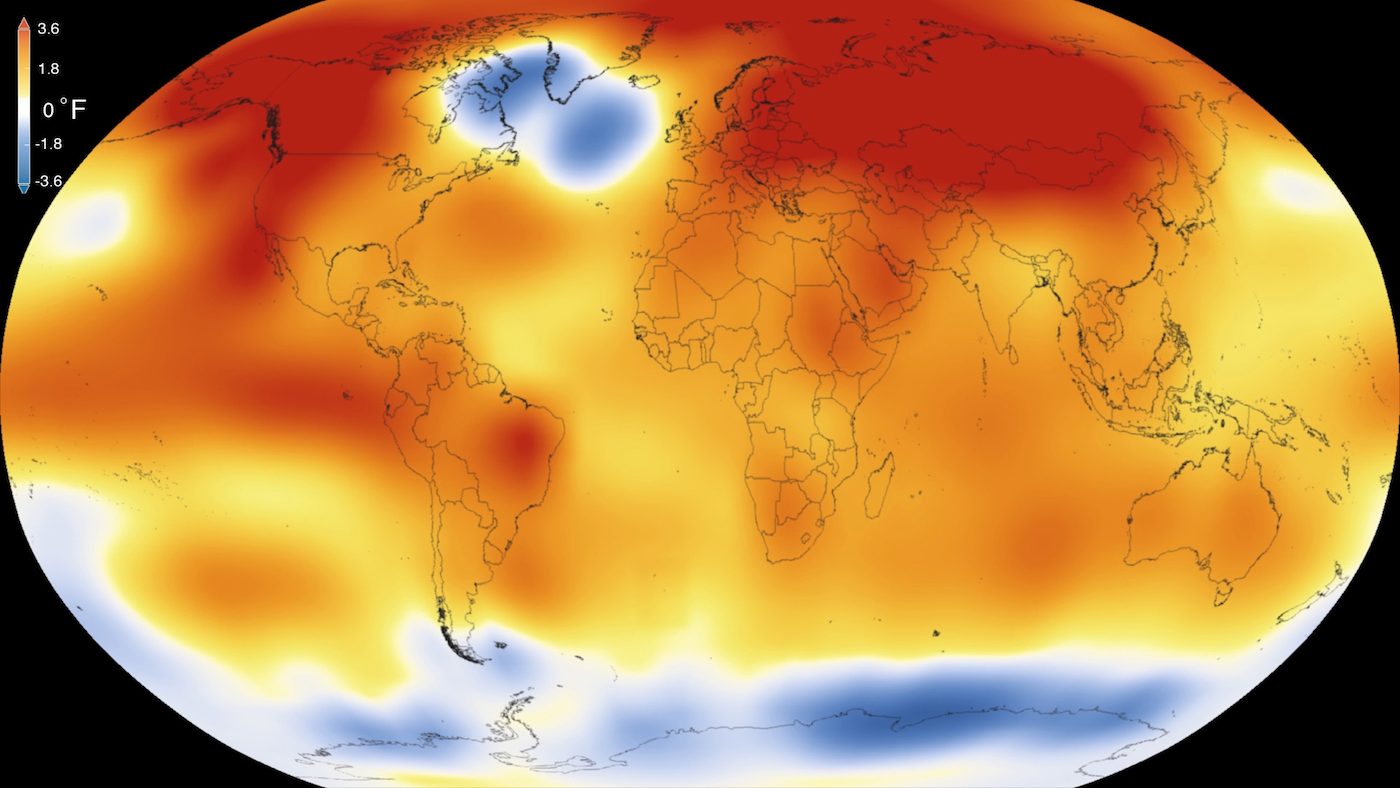

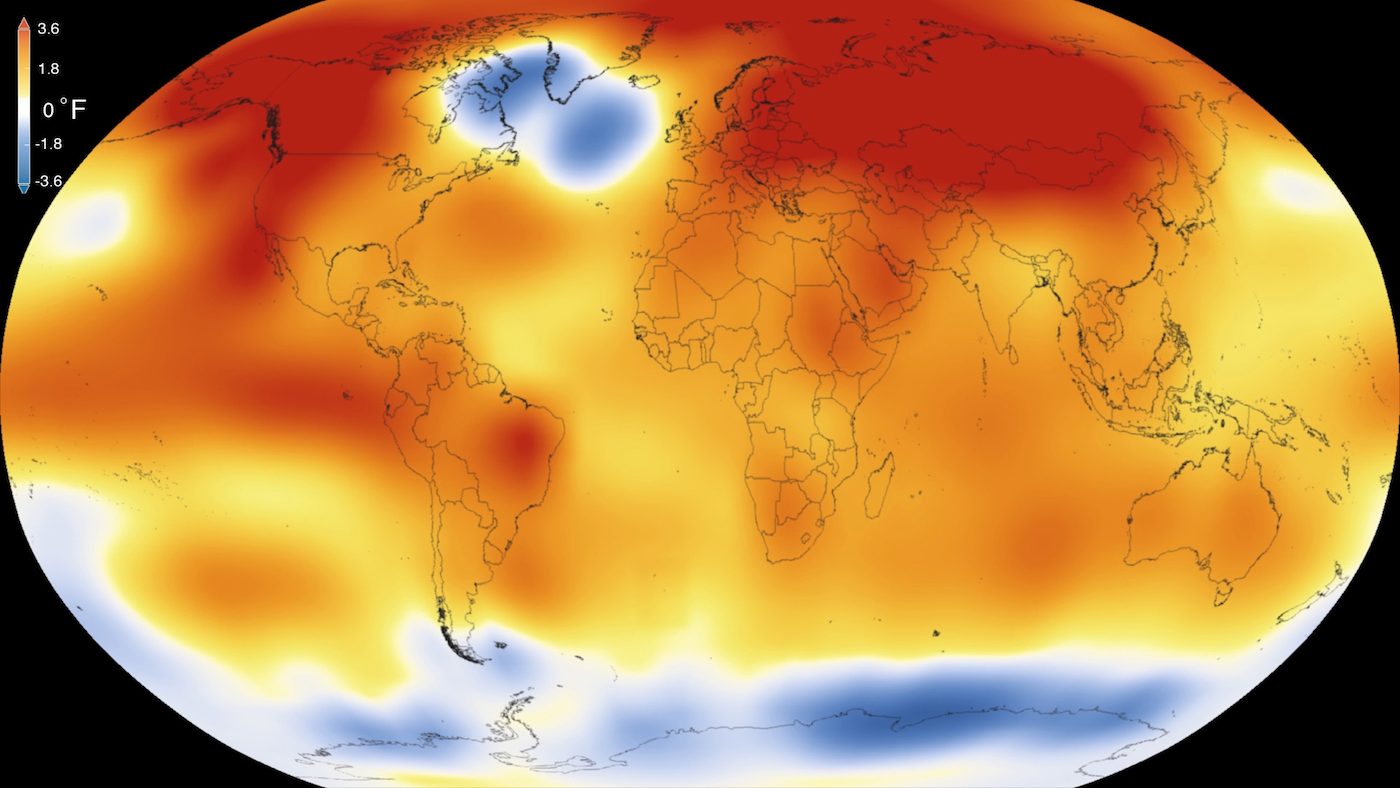

2016 saw the hottest global temperatures ever recorded; 2017, the second hottest year. The 400 parts per million of CO2 barrier has been exceeded – a key indicator of climate change – and the global average temperature continues to climb toward the two-degree Celsius threshold, a level that the international community has agreed should not be breached. This rise is expected to unleash even more erratic and devastating climate events such as the extreme wildfires experienced in the West and the devastating hurricanes that hit Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico. In the U.S., we have long known that climate change is occurring but have failed to take action. Thirty years ago The New York Times reported that Climate Change Has Begun, Expert Tells Senate, but efforts to head off catastrophe have been continually delayed and thwarted by the fossil fuel industry.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 27, 2017 | Women & Radical Feminism

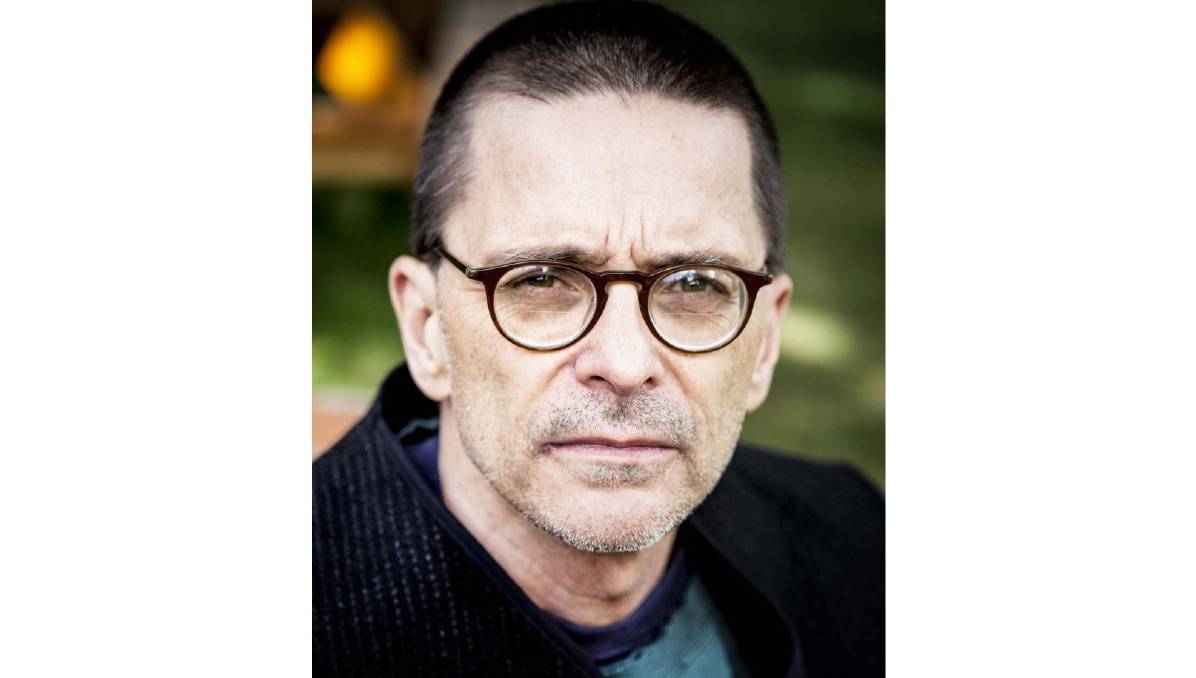

Zoë Goodall interviews Robert Jensen about his most-recent book, “The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men.”

by Zoë Goodall / Feminist Current

This month, I had the fantastic opportunity to speak to Robert Jensen while he was in Australia to launch his new book, The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men (2017, Spinifex Press). As a feminist in my early 20s, I was interested to hear how he thought his book would connect with young men, his thoughts on watering down radical feminism to reach a wider range of people, and how his pro-feminist politics relate to his climate change activism.

~~~

Zoë Goodall: You’ve written extensively about various aspects of feminism and patriarchy. What made you decide to produce a more all-encompassing work that examined patriarchy as a whole?

Robert Jensen: I wrote a book on pornography that was published in 2007 (which has since gone out of print), and the publishers wanted me to do a new edition of it. I didn’t have the emotional energy to go back, specifically, and do new research on pornography, because it’s exhausting to have to look at the misogyny and the racism. I was thinking a lot about how radical feminism has been so marginalized and that there aren’t that many concise explanations of radical feminism in plain language. I also started thinking about how little is written specifically with a male audience in mind.

I’ve always thought that my role in the world is not to tell women what to think about sex/gender/power, but to speak to men, informed by feminism. It just simply seemed to make sense to write, after nearly 30 years of experience, the best plain language account I could of the feminism that helped me to understand the world.

ZG: Did you write The End of Patriarchy for any particular demographic of men, or do you think it’s broadly applicable to all age groups and classes of men?

RJ: I think that the distinctions between men that are important are not primarily among different demographic groups, but internal to them. So, white middle-class men of my age range — some of them are the most sexist human beings I’ve ever met and some of them are the most progressive. The same is true of black urban youth.

Because I teach in a university with a fairly diverse student body, and because I’m out in the world a fair amount, I do see a lot of different men. So I think it’s not that old men are worse than young men, it’s not that white people are worse than black people, that professional men are better than working-class men, you know? I’m sure that there are patterns, but I don’t know enough to know how to describe them. But I’m speaking to anybody within any demographic who wants to think about a radical critique of the sex/gender dynamic, that’s it.

ZG: Over the years, both liberal and radical feminists have expressed sentiments along the lines of “we shouldn’t care what men think — their views aren’t important to us.” Do you think it is important for women in feminism to care about what men think and their viewpoints?

RJ: On one level, the question answers itself. If you were a civil rights activist trying to create an anti-racist society, you should probably think about what white people think, because white people are the source of white supremacy and racism. So in some ways, all women who are feminist and concerned about creating gender justice are thinking about men.

The question is: What role do men have in feminist movements? That is a more difficult question. In the radical feminism that I was exposed to, going back to the late 1980s, rooted in the anti-pornography movement, the understanding was that men had a role in the anti-pornography movement — not to take leadership positions, but to contribute to feminist organizations that were speaking to women as well as to men, specifically about ending the use of pornography, but also about using men’s resources. In terms of contributions to the movement, those resources mean money, time, and energy. That always seemed pretty sensible to me. I was quickly clear that my role was to speak to men and use whatever resources I had, which at this point in my life are a university position which gives me status, some amount of money, and my writing skills.

What I’ve always understood about my own writing is that I’m not the smartest person in the room. I’ve been aware of that for a long, long time. What I also came to understand is that I don’t need to be the smartest person in the room to say something clearly that can be useful, especially to men. And the reason I emphasize that is, in academic life you’re conditioned to always be striving to be the smartest person in the room. In a way, I’m glad I started my academic career in feminism, where clearly my role was not to originate new theory — nobody needed me to start pontificating. My role was to take the existing research, theory, and activism of women — which was considerable — and speak about it in a way that men could understand. And to, where possible, add to research. So I’ve done a lot of interviewing of men, for instance, which is something I can do.

So, instead of, like many academics, trying to figure out how I can get out in front and be the big thinker, I’ve always been comfortable with being an interpreter of the really important ideas of other people, including of all these feminist women who’ve done so much amazing work, and especially Andrea Dworkin. You know, the first feminist work I read was by Andrea Dworkin [pause]. I get really emotional about her, because she had such a huge influence on my life that sometimes when I say her name, I stop and I think, “Oh my god, she’s dead,” you know? And she died so young. But I read Andrea’s work first, and am I going to improve on Andrea Dworkin’s understanding of men and pornography? Not likely. But I can take those insights of hers and ask how I can explore them and how I can talk to men about them. So that’s what I do.

ZG: What are your thoughts on the watering down of radical politics to make them more palatable to more people, versus retaining the ideological purity of the movement? Do you think radical politics are still useful even if they are somewhat defanged?

RJ: I would first of all distinguish between “watering down,” which is always dangerous, and “dejargoning,” if you’ll accept that term. Like any other intellectual, political movement, people can develop an insider language — jargon. And I think jargon is destructive, both to our ability to communicate with others, but also to our own understanding. The minute people start relying on jargon instead of argument, the quality of the intellectual and political position erodes. So I’ve always tried to write without jargon, but to write radically.

I don’t feel a need to water [radical ideas] down, for two reasons. One is I’m an intellectual in the big sense — that society gives me enough money that I don’t have to grow my own food. I get to sit around and think about things. It’s my job, in that sense, to do that. And two, at this point, liberal institutions — capitalism, traditional governance structures, the industrial model for how human beings should operate — aren’t working. At some level, a lot of people know they aren’t working. If you give people only a new version of the same old institutions that people know aren’t working, you’re not going to activate and inspire people. I think what people are looking for, increasingly, is something that is radical. And by that I don’t mean posturing radically — I mean a truly deep critique that goes to the root and speaks to people.

Now, you put a hundred people in a room, a radical analysis is not necessarily going to resonate with [all of them]. But I would rather speak to the percentage of them that are ready for that than to try to create some message that appeals to the broadest possible segment of that room, because that will inevitably lead to a message that doesn’t inspire and won’t be embraced by very many people. At this moment, I’m more convinced than ever that we need to be more radical. But to be radical in plain language.

ZG: Many feminists who are critical of the sex industry refute the accusation that their analysis is based on moralism, most likely because this has been used as a reason to discount their arguments. However, in The End of Patriarchy, you embrace a moral critique of pornography and prostitution, arguing that your position is based, in part, on moral judgments. Were you worried that this statement might create a backlash, not only from defenders of the sex industry, but also from feminists who have rejected claims that their criticisms are based on morals? Why was articulating a moral basis to your objections important to you? Do you think that other men should feel the same?

RJ: I think everybody should feel the same. What I would distinguish is between moral claims and moral principles versus a kind of a moralism used to signify people who assert — with moral certainty — the way you should behave or the way you should use your body, for instance. So I try to avoid being moralistic in that sense — that pejorative sense — but to recognize that we are always, constantly, inextricably moral beings.

Politics is always based on a moral theory of some sort, about what it means to be human. So I use the term “moral” in that larger sense, and I think because the right wing — especially the religious right — has captured the term “morality” and defined it in such narrow ways, many people in the liberal, left, and secular world are afraid of it. I think we need to reclaim it. And the reason is twofold:

1) Principles. Because I don’t think there is a way to develop a politics without basing something on foundationally moral claims.

2) Because everybody really wants moral answers. It’s part of being human.

When the left and the liberals cede that moral turf to the right, the right fills it. And they fill it with what I think are bad answers. So rather than give up that territory and say, “Well we’re not making moral judgments,” I say, “Yes, I’m making moral judgments, and I can articulate them and I can defend them.” Because I think, at some level, people understand there is no decent human community without moral principles. By moral principles I don’t mean, “You can’t use your penis in a certain way,” I mean, “What does it mean to be a human being in relation to other humans? What do we owe ourselves? What do we owe others? How do we understand ourselves in the larger living world?”

All those are profoundly moral questions. Because they have to do with what it means to be a human being. So I embrace that, on both practical and principled grounds.

ZG: Have you noticed men’s attitudes towards women and/or feminism change over the decades? Do you think it’s gotten better or worse?

RJ: I’m going to speak only in the U.S. context, because that’s what I know. In the nearly 30 years I’ve been paying attention to this, the general cultural climate for feminism has gotten better, it’s gotten worse, and it’s stayed the same. Depending on the kinds of issues we’re talking about, all of those things are true.

Let’s take the presence of women in existing institutions: education, government, business. That’s better. We just had an election in which, for the first time, a woman was a major contender for the top political office. That’s an improvement. It doesn’t mean I like Hillary Clinton’s politics, but it’s an improvement — that got better. On some things — take general household relationships, your average heterosexual married couple — I think that’s pretty much the same as it was 30 years ago. I don’t think there have been great improvements in the deepening of a real feminist presence in people’s everyday lives. On the sexual exploitation industries — pornography, prostitution, stripping — it’s far worse, we’ve lost ground. There’s more pornography, there’s more of an acceptance of prostitution than there’s ever been.

So, all of those things are true — that’s the complexity of modern society.

ZG: Do you think young men today have more or less hope of understanding the messages in The End of Patriarchy? Because on the one hand, we’re the generation that’s grown up in a porn culture. But on the other hand, we’re the generation where feminism of a certain kind has become relatively mainstream.

RJ: With experience, there’s the possibility of deeper insight. Yet age and experience can also make it difficult for us to see new ideas. Both things are true. I think my experience suggests that, again, there’s no predicting. Young men who will identify as feminists, but identify with a very kind of weak, liberal, tepid feminism are in some ways as much — maybe even more — of an impediment to making progress than older, lefty guys who may not know how to speak about this so much, but have a more intuitive notion of “justice has to include something around a critique of patriarchy.”

Younger men are growing up in a world that is both more corrosive and also more open to feminism. So how does that balance out? Here’s one way to say it: Are members of fraternities at U.S. universities any more feminist-friendly than they were 40 years ago? Well, they might have learned a certain language. But the fact is, fraternities are still rape factories, and there’s been no significant shift to change that. So, both things are true. Fraternity men know the language, but they don’t care.

ZG: In the concluding chapter of The End of Patriarchy, you talk about the ever-worsening damage to the planet enacted through human activity. Climate change is essentially the definitive crisis of our generation; we’ve been made aware that it’s a problem since we were born, and it’s our generation who needs to fix things before it’s too late. How do you see radical feminism as part of the solution to these ecological crises?

RJ: The connection is twofold: one is intellectual, and the other is more embodied. The two foundational hierarchies in human history, you could say, are the human claim to own the world and men’s claim to own women. After the invention of agriculture, human beings started routinely saying “we own the world”, eventually expanding to “we own every inch of the world and we can do what we want with it”. Patriarchy begins in men’s claims to own women’s bodies, especially reproduction and sexuality. There’s something about this that’s very important, that the two oldest oppressions, in a sense, of patriarchy and human domination of the world, both share this pathological belief that we can own things. And eventually that developed into slavery and believing you can own other humans for labour, and you know, that nation-states can own other territories.

For the last couple of years I’ve really been thinking about how pathological the concept of ownership really is. So if we’re going to deal with reversing the human destruction of our own ecosystem, it’s got to be with rethinking what it means to own. Which to me, among other things, means there is no human future in capitalism, which is premised on the market and the ownership of all.

That’s kind of an analytical answer. There’s always an analytical component to politics, but there’s also an embodied and emotional component, and for me, the feeling is the same. When I listen to women describing their experiences of being prostituted, it’s not just an intellectual response, it’s something deeply human and empathetic in my response in that. I’m from the state of North Dakota, in the U.S., and North Dakota is largely an agricultural state. But in western North Dakota, fracking has opened up an oil industry. I’m not from that part of the state, but it feels like home, in a sense, and when I see pictures of what fracking has done to the land in North Dakota, I cry. There’s a connection, and it’s not because it’s “my land,” it’s because that feels like my part of the world, and there is something being done to destroy that world. It’s a very similar embodied and emotional reaction.

I think there’s something to that. If we are going to deal with the ecological crises, it can’t simply be by analytically deciding we can’t burn fossil fuels anymore, or we need to get solar panels. There’s got to be some way that we transcend our isolation from the larger living world. Modern society keeps you isolated: stay in front of a screen, stay in an air-conditioned house.

We’ve got to deal with that. My first entry into feeling with my own body and understanding my own body was feminism, which told me that all that pornographic culture I had been seduced by was keeping me from myself. There was something profound about that. And I begin the book talking about the bodily experience of coming into feminism.

Zoë Goodall is a student and writer based in Melbourne, Australia. She is currently completing her Honours at RMIT University, examining discussions relating to Indigenous women that occurred during the deliberations on Canada’s Bill C-36. She tweets infrequently at @zcgoodall.