by DGR News Service | Dec 26, 2020 | Repression at Home, White Supremacy

In the first of a three part series this writing lays out the historical context of black and asian movements to reclaim identity and self-worth and a detailed account of the tactics used against them.

By Russell “Maroon” Shoatz/4StruggleMag

“Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission-fulfill it or betray it.” Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

Introduction

Within two generations the youth of this country have come full circle. Starting in 1955, youth were driven by two major motivations: one, the acquiring of enough education or apprenticeships, the use of their unskilled labor or street smarts to land “good” jobs or establish hustles, and to make as much money and obtain as many material trappings as possible. The second was to use the education, apprenticeships, unskilled labor, street smart jobs, hustles and the material trappings provided by them to win a measure of respect and dignity from their peers and society in general.

Simultaneously, they were learning to respect themselves as individuals, and not simply be eating, sleeping, laboring and sexual animals.

The First Wave: circa 1955-1980

The Civil Rights Movement in the South successfully motivated Black, Puerto Rican, Euro-Amerikan, Chicano-Mexicano, Indigenous and Asian youth to use their time, energy, creativity and imagination to discover their true self-worth and earn the respect of the entire world while struggling toward even broader goals that were not measured by one’s material possessions.

Over time each segment cheered on, supported, worked in solidarity with and/or discovered its own common interests and closely linked missions connected to broader people’s goals. Thus, Black youth elevated the Civil Rights Movement to the Black Power and Black Liberation Movements. Puerto Rican youth energized their elders’ ongoing struggle to winindependence for their home island. Euro-Amerikan youth attacked the lies, hypocrisy and oppression that their parents were training them to uphold in the schools, society and overseas. Native Amerikan youth were returning to their suppressed ancestral ways and fighting to regain control over some of their land.

Asian youth were struggling to overcome a system and culture that had always used and abused them. Indeed all of them came to see clearly that neither education, jobs, money, hustles or material trappings could, by themselves, win them the victories they needed, or the new type of dignity and respect they deserved.

Moreover, from 1955 until circa 1975, these youth joined, formulated, led and supported struggles worldwide against racial oppression and bigotry, colonialism, oppression of women and youth. In the process they were winning themselves the respect, admiration and gratitude of the world’s oppressed as well as their peers. Further, in addition to becoming people that societies must take seriously, these youth were positive contributors who had much to give and were willing to sacrifice to achieve their goals. They were youth who were capable of imagining a better world and fighting to realize it while remaining youthful and having a good time doing it. All in all, they earned a much-deserved place in history.

From the Mountain to the Sewer

Yet here we are 30 years later and the youth nowadays have been stripped of that hard-earned freedom, self-respect and dignity. They are being told-over and over-that the only way to regain them is again to acquire education, skills, good jobs, or the right hustle(s). This means, once again, to acquire as much money and material things as one can in order again to win respect and dignity from one’s peers and society-and thereby begin to start loving one’s self, and seeing one’s self as more

than simply an eating, sleeping, working and sexual being.

How the hell did we get back to 1955?

First off, let me make clear that even with all of the glorious strides the youth made within the First Wave, they were not the only ones fighting for radical or revolutionary changes. In fact, more than anything, they were usually only the tip of the spear. They were the shock troops of a global struggle, motivated by

youthful energy and impatience, with no time or temperament for elaborate theories, rushing forward into the fray, ill prepared for the tricks that would eventually overwhelm them.

So to understand what happened, we must examine some of the main “tricks” used to slow down, misdirect, control and defeat them. And without a point, a spear loses all of its advantages.

Strategic Tricks Used Against Them

Understanding these tricks, their various guises and refinements, is the key to everything. You will never really understand what happened to get us to this point, or be able really to move forward, until you recognize and devise ways to defeat them.

They were and remain:

1. Co-option

2. Glamorization of Gangsterism

3. Separation from the most advanced elements

4. Indoctrination in reliance on passive approaches

5. Raw fear

Co-option was used extensively to trick just about all of the First Wave youth into believing that they had won the war. In particular, to every segment of youth, from university students to lower class communities, billions of dollars and resources were made available. This was supposedly for these youth to determine what should be done to carry out far-reaching changes, while in reality they were being expertly monitored and subtly coaxed further and further away from their most radical and advanced elements. This was done mainly through control of the largess, which ultimately was part of the ruling class’ foundation, government and corporate strategy for

defeating the youth with sugar-coated bullets.

In time, consequently, substantial segments of these previously rebellious youth found themselves fully absorbed and neutralized either by directly joining or accepting the foundations’, sub-groups’, corporations’, universities’ or “approved” community groups’ assistance-or by becoming full-fledged junior partners in the system after winning control of thousands of previously out-of-reach political offices. And, for all intents and purposes, that same trick is still being used today.

Glamorization of Gangsterism, however, was then and continues to be the most harmful trick played against the lower class segments.

The males, in particular, were then and continue to be the most susceptible to this gambit, especially when used opposite to prolonged exposure to raw fear! Let me illustrate by briefly describing the histories of two groups that presently enjoy nothing less than “icon” status amongst just about everyone aware of them. These two groups’ “documented histories” clearly show how that trick is played, and continues to be played, throughout this country.

The first of these two groups is the original Black Panther Party, which was bludgeoned and intimidated to the point where its key leader(s) “consciously” steered the group into accepting the Glamorization of Gangsterism. Because this glamorization wasless of a threat to the ruling classes’ interests, it won the Party a temporary respite from the raw fear the ruling circles were levelling against it. In the process the organization was totally destroyed.

The second of the two groups was the Nation of Islam ‘connected’ Black Mafia, which had a different background, but against whom the same tricks were played. It also left in its wake a sordid tale of young Black men who were again turned from seeking to be Liberators into being ruthless oppressors of their own communities.

These men never once engaged their real enemies and oppressors: the ruling class.

Hands down the original Black Panther Party (BPP) won more attention, acclaim, respect, support and sympathy than any other youth group of its time. At the same time the BPP provoked more fear and worry in ruling class circles than any other domestic group since Presidents Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower presided over the neutralization of the working class and the U.S. wing of the Communist Party. The BPP was even more feared than the much larger Civil Rights Movement.

According to the head of the FBI, the Panthers were the “greatest threat to the internal security of the country“. That threat came from the Panthers’ ability to inspire other youth-in the U.S. and globally-to act in similar grassroots political revolutionary ways. Thus, there were separate BPP-style formations amongst Native Amerikans (the American Indian Movement); Puerto Ricans(the Young Lords); Chicano Mexicano Indigenous people (the Brown Berets); Asians (I Wor Kuen); Euro-Amerikan (the Young Patriot and White Panther Parties); and even the elderly (the Gray Panthers). Also, there were literally hundreds of other similar, lesser known groups!

Internationally the BPP had an arm in Algeria that had the only official “Embassy” established amongst all of the other Afrikan, Asian and South Amerikan revolutionary groups seeking refuge in that then-revolutionary country. Astonishingly, the BPP even inspired separate Black Panther Parties in India, the Bahamas, Nova Scotia, Australia and Occupied Palestine/State of Israel!

On the other hand, the Nation of Islam (NOI) had been active since 1930. Yet it also experienced a huge upsurge in membership in the same period. This was mainly due to the charismatic personality of Malcolm X and his aggressive recruitment techniques. Malcolm’s influence carried on after his assassination, fueled by the overall rebellious spirits of the youth looking for groups which would lead them to fight against the system.

Therefore, there’s a mountain of documents which clearly show that the highest powers in this country classified both groups as Class A Threats to be neutralized or destroyed. These powers mused that if that goal could be achieved, they could then use similar methods to defeat the rest of the youth.

So how did they do it?

Against the BPP the powers used a combination of co-option, glamorization of gangsterism, separation from the most advanced elements, indoctrination in reliance on passive approaches and raw fear; that is, every trick in the book. Thus, fully alarmed at the growth and boldness of the BPP and related groups as well as their ability to win a level of global support, the ruling classes’ governmental, intelligence, legal and academic arms devised a strategy to split the BPP and co-opt its more compliant elements. At the same time they moved totally to annihilate its more radical and revolutionary remainders.

They knew they had the upper hand due to the youth and inexperience of the BPP; and they had their own deep well of resources and experiences in using counter-insurgency techniques much earlier against:

- Marcus Garvey’s UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement

Association);

- the Palmer Raids against Euro-Amerikans of an Anarchist

and/or left Socialist bent;

- the crushing of the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World)

and neutralizing of the other Socialists;

- their subsequent destruction of any real Communist power in

Western Europe;

- their total domination and subjugation of the Caribbean

(except Cuba), Central and South Amerika-except for the fledgling guerilla movements;

- and everything they had learned in their wars to replace the

European colonial powers in Africa and Asia.

Still, the BPP had highly motivated cadre, imbued with a

fearlessness little known among domestic groups. The ruling class and its henchmen were stretched thin, especially since the Vietnamese, Laotians and Kampucheans were kicking their ass in Southeast Asia. Moreover, the freedom fighters in Guinea-Bissau and Angola had the U.S.’ European allies-whom the U.S. supplied with the latest military hardware-on the run. So although the BPP was inexperienced, the prospect of neutralizing it was a mixed bag.

The members of the BPP still had a fighting chance.

The co-option depended on them neutralizing the BPP co-founder and by-then icon, Huey P. Newton. Afterward, they used him-along with other methods-to split the BPP and lead his wing along reformist lines. It was hoped that this process would force the still-revolutionary wing into an all-out armed fight before it was ready, either killing, jailing, exiling or breaking its members will to resist or sending them into ineffective hiding-out.

At this time, even with the BPP’s extraordinary global stature, no country seemed to want to risk the U.S. wrath by “openly” allowing the BPP to train guerilla units, something which, given more time, could nevertheless have come to pass. So, surprisingly, Huey was allowed to leave jail with a still-tobe-tried-murder-of-a-policeman charge pending. Thus, the government and courts had him on a short leash, and with it they hoped to control his actions, although probably not through any direct agreements. Sadly, the still politically naive BPP cadre and the other youth who looked up to Newton could imagine “nothing” but that “they”-the people-had forced his release.

Veterans from those times still insist on clinging to such tripe!

Yet it seems Newton thought otherwise, and since he was not prepared to go underground and join his fledgling Black Liberation Army (BLA), he almost immediately began following a reformist script. This was completely at odds with his own earlier theories and writings, as well as at odds with basic principles that were being practiced to good effect by oppressed people throughout the world.

Even further, he used his almost complete control of the BPP Central Committee to expel many, many veteran and combat-tested BPP cadre in an imitation of the Stalinist and Euro-gangster posture he would later become famous for. This included an all-out shooting war to repress any BPP members who would not accept his independently derived-at reformist policies.

At the same time, on a parallel track, U.S. and local police and intelligence agencies were using their now infamous COINTELPRO operations to provoke the split between the wing Huey dominated and other, less compliant BPP members. This finally reached a head in 1971, after Huey’s shooting war and purge forced scores of the most loyal, fearless and dedicated above-ground BPP to go underground and join those other BPP members who were already functioning there as the offensive armed wing. Panther Wolves, AfroAmerican Liberation Army and Black Liberation Army were all names by which these members were known, but the latter is the only one that would stick.

At this time the BLA was a confederation of clandestine guerilla units composed of mostly Black Revolutionary Nationalists from a number of different formations.

Nevertheless, they still accepted the BPP’s leadership and Huey Newton as their Minister of Defense. But obviously Newton didn’t see it that way. Even more telling, it was later learned that Newton’s expensive penthouse apartment-where he and other Central Committee members handled any number of sensitive BPP issues, was under continuous surveillance by intelligence agents who had another apartment down the hall. Thus, Newton and his faction were encapsulated, leaving them unable to follow anything but government sanctioned scripts; unless he/they went underground.

This only occurred when Newton fled to Cuba after his gangster antics threatened the revocation of his release on the pending legal matters which the government held over his head. Add to that, the glamorization of gangsterism was something that various ruling class elements had begun to champion and direct toward the Black lower classes, in particular. This occurred especially after they saw how much attention the Black Arts Movement was able to generate. Indeed, these ruling class elements recognized it could be used to misdirect youthful militancy while still being hugely profitable. They had, in fact, already misdirected Euro-Amerikan and other youth with the James Bond-I Spy-Secret Agent Man and other replacements for the “Old West/Cowboys and Indians” racist crap, so why not a “Black” counterpart? Thus was born the enormously successful counter-insurgency genre collectively known as the

Blacksploitation movies: Shaft, Superfly, Foxxy Brown, Black Caesar and the like, accompanied by wannabe crossovers like Starsky and Hutch, and the notorious Black snitch Huggie Bear.

Psychological warfare!

Follow the psychology: You can be “Black”, cool, rebellious, dangerous, rich, have respect, women, cars, fine clothes, jewelry, an expensive home and even stay high; as long as you don’t fight the system-or the cops! But, if you don’t go along with that script, then get ready to go back to the early days-with its shootouts with the cops, graveyard, prison, on the run and exile! Or you can be cool even as a Huggie Bear-style snitch, and interestingly, like his buddy, the post-modern/futuristic rat Cipher of The Matrix, who tried to betray ZION in return for a fake life as a rich, steak-eating, movie star. And most important: no more fighting with the Agents! Get it?

In addition, the ruling classes bolstered the government’s assault by flooding our neighborhoods with heroin, cocaine, marijuana and “meth”. In the process they saddled the oppressed with a Trojan Horse which would strategically handicap them for decades to come. All of those drugs had earlier been introduced to these areas by organized criminals under local police and political protection. But now the intelligence agencies were using them with the same intentions that alcohol had long ago been introduced to the Native

Amerikans and opium had been trafficked by the ruling classes of Europe and this country: to counter the propensities of oppressed people to rebel against outside control while profiting off their misery.

Against this background Newton began to indulge in drugs to try to relieve the stress of all that he was facing. He became a drug addict, plain and simple. That, however, didn’t upset the newly-constructed gangster/cool that Hollywood, the ruling class and the government were pushing. Although many BPP cadre and other outsiders were very nervous about it, Newton’s control was by then too firmly fixed for anyone to challenge-except for the BLA, whose members were by then in full blown urban guerilla war with the government.

At the same time, the reformist wing of the BPP did manage to make some noteworthy strides under its only female head, Elaine Brown. Newton’s drug addiction/gangster-lifestyle-provoked exile caused him to “appoint”-on his own and without any consultation with the body-Elaine to head the Party in his absence.

An exceptionally gifted woman:

she relied on an inner circle of female BPP cadre, backed up by male enforcers, to introduce some clear and consistent projects that helped the BPP to become a real power locally. It was a reformist paradigm, though, that could not hope to achieve any of the radical/revolutionary changes called for earlier. On the contrary, Newton in his earlier writings had put the cadre on notice of a point when, in order to keep moving forward, the aboveground would have to be supported by an underground. Yet it was Newton who completely rejected that paradigm upon being released from jail, although he still organized and controlled a heavily armed extortion group called “The Squad”, which consisted of BPP cadre who terrorized Oakland’s underworld with a belt-operated machine gun mounted on a truck bed and accompanied by cadre who were ready for war!

In classic Eurogangster fashion, Newton had turned to preying on segments of the community that he had earlier vowed to liberate. But, of course, the police and government were safe from his forces. With no connection to a true undergound-the BLA-there was no rational way to ratchet up the pressure on the police, government and the still fully operational system of ruling class control and oppression. Newton and his followers had been reduced to completely sanctioned methods. Consequently we can see all of the government’s tricks bearing fruit. In a seemingly curious combination of Co-option, Indoctrination in Reliance on Passive Approaches (that is, passive toward the status quo), and Glamorization of Gangsterism, Newton’s faction of the BPP had limited itself both to legal and underworld-sanctioned methods.

They also fell for the trick of Separation from the Most Advanced Elements by severing all relations with their armed underground,the BLA, whose members would lead the BPP if the Party got to the next level of struggle-open armed resistance to the oppressors. Finally, Newton, his faction and activists from all of the other Amerikan radical and revolutionary groups succumbed to the terror and Raw Fear that was being levelled on them. The exception was those who waged armed struggle, who themselves were killed, jailed, exiled, forced into deep hiding or into continuing their activism under the radar.

Epilogue on Huey P. Newton and his BPP faction:

Elaine Brown both guided Newton’s and her faction to support Newton and his family in exile while orchestrating the building up of enough political muscle in Oakland to assure his return on favorable terms. Thus, Newton did return and eventually the charges were dropped. Nevertheless, Newton continued to use his iconic stature and renewed direct control of his faction again to play the cool-political-gangster role; and like any drug addict who refuses to reform, he kept sliding downhill, even turning on old comrades and his main champion, Elaine Brown, who had to flee in fear. Sadly, for all practical purposes, that was the end of the original Black Panther Party.

Check-mate!

Later, as is well-known, Newton’s continued drug addiction cost him his life, a sorry ending for a once great man.

The second part of this series will be published on the 27th December 2020. Original artwork was created for this piece by Siri: thank you!

To learn more about the Black Panther Party:

1. The Wretched of the Earth, by Frantz Fanon

2. We Want Freedom, by Mumia Abu Jamal

3. Assata: An Autobiography, Assata Shakur

4. A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story, by Elaine Brown

5. Blood in My Eye, by George Jackson

6. We Are Our Own Liberators: On The BLA, by J. A. Muntaquim

7. Liberation, Imagination & the Black Panther Party, by Kathleen Cleaver & G. Katificas

by DGR News Service | Oct 4, 2020 | Listening to the Land

This piece is a brief excerpt from Brian Doyle‘s book “The Plover“. Doyle offers the reader a description of the neverending ebb and flow of life in the Pacific Ocean and human hunger for a ‘story’.

Featured image: Big Island, Hawaii via Unsplash

Consider, for a moment, the Pacific Ocean not as a vast waterway, not as a capacious basin for liquid salinity and the uncountable beings therein, nor as a scatter of islands still to this day delightfully not fully and accurately counted, but as a country in and of itself, dressed in bluer clothes than the other illusory entities we call countries, that word being mere epithet and label at best, and occasion and excuse for murder at worst; rather consider the Pacific a tidal continent, some ten thousand miles long and ten thousand miles wide, bordered by ice at its head and feet, by streaming Peru and Palau at its waist; on this continent are the deepest caves, the highest mountains, the loneliest prospects, the emptiest aspects, the densest populations, the most unmarked graves, the least imprint of the greedy primary ape; in this continent are dissolved beings beyond count, their shells and ships and fins and grins; so that the continent, ever in motion, drinks the dead as it sprouts new life; the intimacy of this closer and blunt and naked in Pacifica than anywhere else, by volume; volume being an apt and suitable word to apply to that which is finally neither ocean nor continent but story always in flow, narrative that never pauses, endless ebb and flow, wax and wane, a book with no beginning and no end; from it emerged the first fundament and unto it shall return the shatter of the world that was, the stretch between a page or two of the unimaginable story; but while we are on this page we set forth on journeys, on it and in it, steering by the stars, hoping for something we cannot explain; for thousands of years we said gold and food and land and power and freedom and knowledge and none of those were true even as all were true, as shallow waters; we sail on it and in it because we are starving for story, our greatest hunger, our greatest terror; and we love most what we must have but can never have; and so on we go, west and then west.

You can find and/or buy a copy of the book “The Plover” here:

https://www.indiebound.org/book/9781250062451

by DGR News Service | Sep 15, 2020 | Climate Change, Mining & Drilling, The Problem: Civilization

This is the fourth part in the series. In the previous essays, we have explored the need for a collapse, the relationship between a Dyson sphere and overcomsumption, and our blind pursuit for ‘progress.’ In this piece, Elisabeth describes how the Dyson sphere is an extension of the drive for so-called “green energy.”

By Elisabeth Robson

Techno-utopians imagine the human population on Earth can be saved from collapse using energy collected with a Dyson Sphere–a vast solar array surrounding the sun and funneling energy back to Earth–to build and power space ships. In these ships, we’ll leave the polluted and devastated Earth behind to venture into space and populate the solar system. Such a fantasy is outlined in “Deforestation and world population sustainability: a quantitative analysis” and is a story worthy of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. It says, in so many words: we’ve trashed this planet, so let’s go find another one.

In their report, Mauro Bologna and Gerardo Aquino present a model that shows, with continued population growth and deforestation at current rates, we have a less than 10% chance of avoiding catastrophic collapse of civilization within the next few decades. Some argue that a deliberate and well-managed collapse would be better than the alternatives. Bologna and Aquino present two potential solutions to this situation. One is to develop the Dyson Sphere technology we can use to escape the bonds of our home planet and populate the solar system. The other is to change the way we (that is, those of us living in industrial and consumer society) live on this planet into a ‘cultural society’, one not driven primarily by economy and consumption, in order to sustain the population here on Earth.

The authors acknowledge that the idea of using a Dyson Sphere to provide all the energy we need to populate the solar system is unrealistic, especially in the timeframe to avoid collapse that’s demonstrated by their own work. They suggest that any attempt to develop such technology, whether to “live in extraterrestrial space or develop any other way to sustain population of the planet” will take too long given current rates of deforestation. As Salonika describes in an earlier article in this series, “A Dyson Sphere will not stop collapse“, any attempt to create such a fantastical technology would only increase the exploitation of the environment.

Technology makes things worse

The authors rightly acknowledge this point, noting that “higher technological level leads to growing population and higher forest consumption.” Attempts to develop the more advanced technology humanity believes is required to prevent collapse will simply speed up the timeframe to collapse. However, the authors then contradict themselves and veer back into fantasy land when they suggest that higher technological levels can enable “more effective use of resources” and can therefore lead, in principle, to “technological solutions to prevent the ecological collapse of the planet.”

Techno-utopians often fail to notice that we have the population we do on Earth precisely because we have used technology to increase the effectiveness (and efficiency) of fossil fuels and other resources* (forests, metals, minerals, water, land, fish, etc.). Each time we increase ‘effective use’ of these resources by developing new technology, the result is an increase in resource use that drives an increase in population and development, along with the pollution and ecocide that accompanies that development. The agricultural ‘green revolution’ is a perfect example of this: advances in technology enabled new high-yield cereals as well as new fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, irrigation, and mechanization, all of which prevented widespread famine, but also contributed to an ongoing explosion in population, development, chemical use, deforestation, land degradation and salinization, water pollution, top soil loss, and biodiversity loss around the world.

As economist William Stanley Jevons predicted in 1865, increasing energy efficiency with advances in technology leads to more energy use. Extrapolating from his well-proved prediction, it should be obvious that new technology will not prevent ecological collapse; in fact, such technology is much more likely to exacerbate it.

This mistaken belief that new technology can save us from collapse pervades the policies and projects of governments around the world.

Projects like the Green New Deal, the Democrat Party’s recently published climate plan, and the UN’s sustainable development goals and IPCC recommendations. All these projects advocate for global development and adoption of ‘clean technology’ and ‘clean industry’ (I’m not sure what those terms mean, myself); ’emissions-free’ energy technologies like solar, wind, nuclear and hydropower; and climate change mitigation technologies like carbon capture and storage, smart grids, artificial intelligence, and geo-engineering. They tout massive growth in renewable energy production from wind and solar, and boast about how efficient and inexpensive these technologies have become, implying that all will be well if we just keep innovating new technologies on our well worn path of progress.

Miles and miles of solar panels, twinkling like artificial lakes in the middle of deserts and fields; row upon row of wind turbines, huge white metal beasts turning wind into electricity, and mountain tops and prairies into wasteland; massive concrete dams choking rivers to death to store what we used to call water, now mere embodied energy stored to create electrons when we need them–the techno-utopians claim these so-called clean’ technologies can replace the black gold of our present fantasies–fossil fuels–and save us from ourselves with futuristic electric fantasies instead.

All these visions are equally implausible in their capacity to save us from collapse.

And while solar panels, wind turbines, and dams are real, in the sense that they exist–unlike the Dyson Sphere–all equally embody the utter failure of imagination we humans seem unable to transcend. Some will scoff at my dismissal of these electric visions, and say that imagining and inventing new technologies is the pinnacle of human achievement. With such framing, the techno-utopians have convinced themselves that creating new technologies to solve the problems of old technologies is progress. This time it will be different, they promise.

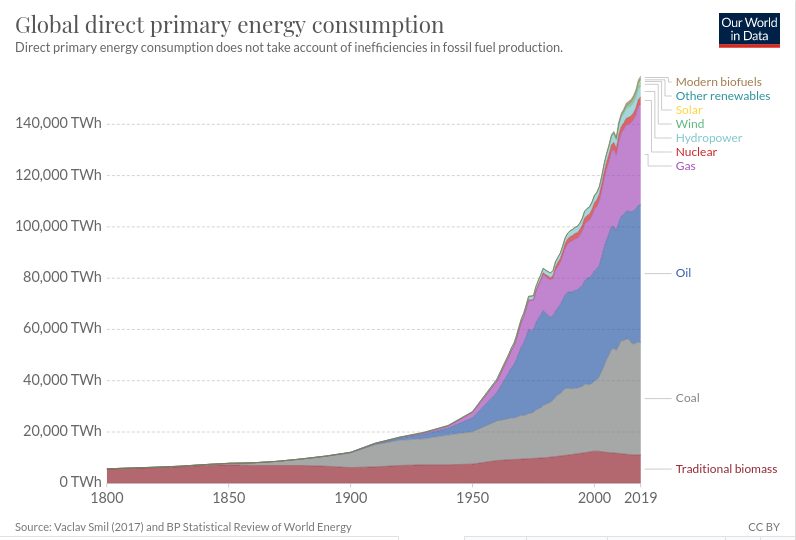

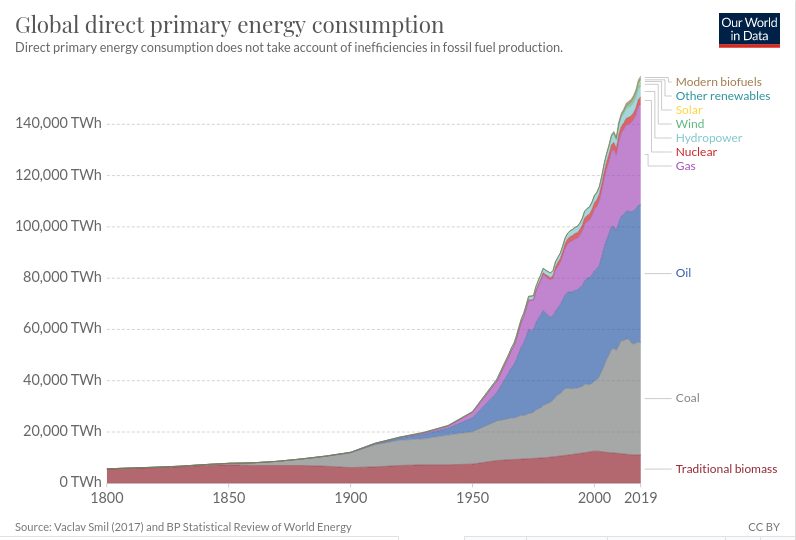

And yet if you look at the graph of global primary energy consumption:

it should be obvious to any sensible person that new, so-called ‘clean’ energy-producing technologies are only adding to that upward curve of the graph, and are not replacing fossil fuels in any meaningful way. Previous research has shown that “total national [US] energy use from non-fossil-fuel sources displaced less than one-quarter of a unit of fossil-fuel energy use and, focussing specifically on electricity, each unit of electricity generated by non-fossil-fuel sources displaced less than one-tenth of a unit of fossil-fuel-generated electricity.”

In part, this is due to the fossil fuel energy required to mine, refine, manufacture, install, maintain, and properly dispose of materials used to make renewable and climate mitigation technologies. Mining is the most destructive human activity on the planet, and a recent University of Queensland study found that mining the minerals and metals required for renewable energy technology could threaten biodiversity more than climate change. However, those who use the word “clean” to describe these technologies conveniently forget to mention these problems.

Wind turbines and solar arrays are getting so cheap; they are being built to reduce the cost of the energy required to frack gas: thus, the black snake eats its own tail. “Solar panels are starting to die, leaving behind toxic trash”, a recent headline blares, above an article that makes no suggestion that perhaps it’s time to cut back a little on energy use. Because they cannot be recycled, most wind turbine blades end up in landfill, where they will contaminate the soil and ground water long after humanity is a distant memory. Forests in the southeast and northwest of the United States are being decimated for high-tech biomass production because of a loophole in EU carbon budget policy that counts biomass as renewable and emissions free. Dams have killed the rivers in the US Pacific Northwest, and salmon populations are collapsing as a result. I could go on.

The lies we tell ourselves

Just like the Dyson Sphere, these and other technologies we fantasize will save our way of life from collapse are delusions on a grand scale. The governor of my own US state of Washington boasts about how this state’s abundant “clean” hydropower energy will help us create a “clean” economy, while at the same time he fusses about the imminent extinction of the salmon-dependent Southern Resident Orca whales. I wonder: does he not see the contradiction, or is he willfully blind to his own hypocrisy?

The face of the Earth is a record of human sins (1), a ledger written in concrete and steel; the Earth twisted into skyscrapers and bridges, plows and combines, solar panels and wind turbines, mines and missing mountains; with ink made from chemical waste and nuclear contamination, plastic and the dead bodies of trees. The skies, too, tell our most recent story. Once source of inspiration and mythic tales, in the skies we now see airplanes and contrails, space junk and satellites we might once have mistaken for shooting stars, but can no longer because there are so many; with vision obscured by layers of too much PM2.5 and CO2 and NOx and SO2 and ozone and benzene. In the dreams of techno-utopians, we see space ships leaving a rotting, smoking Earth behind.

One of many tales of our Earthly sins is deforestation.

As the saying goes, forests precede us, and deserts follow; Mauro Bologna and Gerardo Aquino chose a good metric for understanding and measuring our time left on Earth. Without forests, there is no rain and the middles of continents become deserts. It is said the Middle East, a vast area we now think of as primarily desert, used to be covered in forests so thick and vast the sunlight never touched the ground (2). Without forests, there is no home for species we’ve long since forgotten we are connected to in that web of life we imagine ourselves separate from, looking down from above as techno-gods on that dirty, inconvenient thing we call nature, protected by our bubble of plastic and steel. Without forests, there is no life.

One part of one sentence in the middle of the report gives away man’s original sin: it is when the authors write, “our model does not specify the technological mechanism by which the successful trajectories are able to find an alternative to forests and avoid collapse“. Do they fail to understand that there is no alternative to forests? That no amount of technology, no matter how advanced–no Dyson Sphere; no deserts full of solar panels; no denuded mountain ridges lined with wind turbines; no dam, no matter how wide or high; no amount of chemicals injected into the atmosphere to reflect the sun–will ever serve as an “alternative to forests”? Or are they willfully blind to this fundamental fact of this once fecund and now dying planet that is our only home?

A different vision

I’d like to give the authors the benefit of the doubt, as they end their report with a tantalizing reference to another way of being for humans, when they write, “we suggest that only civilisations capable of a switch from an economical society to a sort of ‘cultural’ society in a timely manner, may survive.” They do not expand on this idea at all. As physicists, perhaps the authors didn’t feel like they had the freedom to do so in a prestigious journal like Nature, where, one presumes, scientists are expected to stay firmly in their own lanes.

Having clearly made their case that civilized humanity can expect a change of life circumstance fairly soon, perhaps they felt it best to leave to others the responsibility and imagination for this vision. Such a vision will require not just remembering who we are: bi-pedal apes utterly dependent on the natural world for our existence. It will require a deep listening to the forests, the rivers, the sky, the rain, the salmon, the frogs, the birds… in short, to all the pulsing, breathing, flowing, speaking communities we live among but ignore in our rush to cover the world with our innovations in new technology.

Paul Kingsnorth wrote: “Spiritual teachers throughout history have all taught that the divine is reached through simplicity, humility, and self-denial: through the negation of the ego and respect for life. To put it mildly, these are not qualities that our culture encourages. But that doesn’t mean they are antiquated; only that we have forgotten why they matter.”

New technologies, real or imagined, and the profits they bring is what our culture reveres.

Building dams, solar arrays, and wind turbines; experimenting with machines to capture CO2 from the air and inject SO2 into the troposphere to reflect the sun; imagining Dyson Spheres powering spaceships carrying humanity to new frontiers–these efforts are all exciting; they appeal to our sense of adventure, and align perfectly with a culture of progress that demands always more. But such pursuits destroy our souls along with the living Earth just a little bit more with each new technology we invent.

This constant push for progress through the development of new technologies and new ways of generating energy is the opposite of simplicity, humility, and self-denial. So, the question becomes: how can we remember the pleasures of a simple, humble, spare life? How can we rewrite our stories to create a cultural society based on those values instead? We have little time left to find an answer.

* I dislike the word resources to refer to the natural world; I’m using it here because it’s a handy word, and it’s how most techno-utopians refer to mountains, rivers, rocks, forests, and life in general.

(1) Susan Griffin, Woman and Nature

(2) Derrick Jensen, Deep Green Resistance

In the final part of this series, we will discuss what the cultural shift (as described by the authors) would look like.

Featured image: e-waste in Bangalore, India at a “recycling” facility. Photo by Victor Grigas, CC BY SA 3.0.

![[The Ohio River Speaks] Can a River Save Your Life?](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2020/06/Can-A-River-Save-Your-Life.jpg)

by DGR News Service | Jun 13, 2020 | Listening to the Land

In this writing, taken from ‘The Ohio River Speaks‘, Will Falk describes the urgency in which he seeks to protect the natural world. Through documenting the journey with the Ohio River he strengthens others fighting to protect what is left of the natural world. Read the first part of the journey here.

By Will Falk/The Ohio River Speaks

Can a River Save Your Life?

The first headwaters of my journey with the Ohio River are located in despair. Despair and I have a long-term, intimate relationship.

Seven years ago, I tried to kill myself. Twice.

Suicidal despair is a failure to envision a livable future. The future never comes, so the future is built with the only materials at hand – experience. At times, my experience is so painful, and the pain lasts so long that, when I peer into the future, I only see more pain. When this happens, I sometimes ask: If life is so painful, if life will only remain so painful, why go on living?

I cling to my reason. I live for my family. I have seen the pain my two suicide attempts have caused my mother, father, and sister. My family also includes the natural world. I have been enchanted by the stories the Colorado River tells. I have watched the stars next to ahinahina (silverswords) on the slopes of Mauna Kea. I have seen a great horned owl dance on setting sunlight filtered through pinyon-pine needles.

This doesn’t mean, however, that I do not experience despair anymore.

Sometime last year, a spark flew from our shared global experience to fall into a tinderbox of my recent personal experiences and ignited the strongest inferno of despair I’ve felt in a long time.

I ended a long-term romantic partnership with a woman who, at one time, I thought was the love of my life. I moved in to my parents’ basement in Castle Rock, CO. And, an environmental organization I love working for almost internally combusted.

These realities are personally painful. But, they’re not unique. It is a global reality – the intensifying destruction of the natural world – that is the deepest source of my despair.

The love I feel for my mother and father, for my sister, for rivers, mountains, and forests, for ahinahina, great-horned owls, and pinyon-pines makes me deeply vulnerable. It wasn’t until I noticed the way people have been obsessively tracking confirmed cases of COVID-19 that I realized most people do not pore over studies about rates of ecological collapse like I do.

While COVID-19 is very scary, I find reports like the one from Living Planet Index and the Zoological Society of London in 2018 documenting a gut-wrenching 60% decline in the size of mammal, bird, fish, reptile, and amphibian populations in just over 40 years to be even scarier.

I am cursed with a profound sense of urgency to stop the destruction of the planet.

If millions of people are killed every year by air pollution, then each passing year is, to me, a heinous disaster. If dozens of species are driven to extinction every day, then each passing day is an unspeakable tragedy. If thousands of acres of forest are cleared every hour, then each passing hour is a horrific loss.

If all these things are true, then each passing moment screams more loudly than the last for the destruction to stop. I haven’t found many others who possess a similar sense of urgency. I haven’t even found many others who possess this sense of urgency among fellow environmentalists. The lack of urgency displayed by environmentalists is especially frustrating because environmentalists are aware of the problems we face. Despite this awareness, most environmentalists are still drinking a stale Kool-Aid brewed with the substanceless sugar of ineffective tactics.

For example, I am a practicing rights of nature attorney. In 2017, I helped to file a first-ever federal lawsuit seeking rights for a major ecosystem, the Colorado River. For the past few years, I’ve worked for a nonprofit law firm, the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), that has developed a strategy for enshrining rights of Nature in American law.

American law defines Nature merely as property. Property is an object that can be consumed and destroyed. CELDF’s strategy, specifically, and rights of Nature, generally, seek to transform the status of Nature from that of property to that of a rights-bearing entity. This is similar to how ending American slavery required transforming the legal definition of African Americans as property into African Americans as rights-bearing citizens. Those with rights have power over those without rights.

And, in a culture based on competition, those with rights oppress those without rights.

A key component of CELDF’s strategy involves helping communities affected by environmental destruction to use their local lawmaking functions to enact laws granting Nature the rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and naturally evolve. These laws also give Nature legal “personhood” which empowers community members to bring lawsuits to enforce Nature’s rights. Currently, under American law, if community members want to sue to stop environmental destruction, they must frame the problem as violating their rights as citizens. It is often more difficult to prove that environmental destruction directly harms humans than it is to prove that an activity harms an ecosystem.

If Nature was recognized as a legal person and communities simply had to prove that an activity violated the rights of Nature, then many destructive activities would become illegal. On the surface this may seem like a great strategy. However, this strategy depends on convincing too many people in power, who directly benefit from the status quo, to embrace and enforce rights of Nature. The powerful derive their power by exploiting Nature. Enforcing Nature’s rights would undermine their power. This is why they react so violently whenever their power is truly threatened. Even if convincing all these people to give up their power is possible, it will likely take decades to change the legal system into one that respects rights of Nature.

In CELDF, we are working hard to reinvent our strategy to reflect the recognition that legal change, by itself, is taking far too long.

Nevertheless, most tactics employed by environmentalists are based on achieving a voluntary transition to a sane and Earth-based culture. But, do we really think this voluntary transition is possible? And, even if we do, don’t we have to admit that this voluntary transition is taking a long time? As time slips away – and so much is destroyed and so many are murdered – shouldn’t we be most concerned with stopping the dominant culture as quickly as possible? When I suggest that we have an open and frank conversation about what it will take to truly stop the destruction, I am often dismissed as being unrealistic and too extreme.

This causes me to despair. When I despair for too long I become depressed and anxious. When I am depressed and anxious I shake, tremble, fidget, and pace. Over the years, I’ve learned that when this happens, my body is telling me to move. Unsurprisingly, one of the best medicines I’ve found for mental illness is exercise. Lately, though, my typical regimen for managing despair hasn’t been working. No matter how much I exercise, no matter how much stress I shed from my day, no matter who I spend time with, the flames of despair keep on licking the edges of my consciousness. The lack of urgency I find reflected around me also causes me to question my perception of reality.

Are things really as bad as I think they are?

It is natural to seek validation from other humans. But, most humans I know would rather not join me in my despair. Psychologist R.D. Laing in The Politics of Experience was correct when he wrote:

“If Jack succeeds in forgetting something, this is of little use if Jill continues to remind him of it. He must induce her not to do so. The safest way would be not just to make her keep quiet about it, but to induce her to forget it also.

Jack may act upon Jill in many ways. He may make her feel guilty for keeping on ‘bringing it up.’ He may invalidate her experience. This can be done more or less radically. He can indicate merely that it is unimportant or trivial, whereas it is important and significant to her. Going further, he can shift the modality of her experience from memory to imagination: ‘It’s all in your imagination.’ Further still, he can invalidate the content: ‘It never happened that way.’ Finally, he can invalidate not only the significance, modality, and content, but her very capacity to remember at all, and make her feel guilty for doing so into the bargain.

This is not unusual. People are doing such things to each other all the time. In order for such transpersonal invalidation to work, however, it is advisable to overlay it with a thick patina of mystification. For instance, by denying that this is what one is doing, and further invalidating any perception that it is being done by ascriptions such as ‘How can you think such a thing?’ ‘You must be paranoid.’ And so on…”

Similarly, it is easy to seek answers from television and computer screens. The internet provides more access to certain forms of information – like graphs, statistics, and written reports – than ever before. However, answers provided by graphs, statistics, and written reports will always be secondhand. I do not want to risk the invalidation of the experience of others that many humans are so adept at. Neither do I want to settle for secondhand answers.

I want to see for myself.

Earth is vast. Ecocide is extensive. I have neither the time nor the resources to rely solely on firsthand knowledge. Fortunately, the Ohio River is vast enough to implicate global reality while remaining small enough for me to witness with my limited budget and finite time. Meanwhile, my body urges me to move. So, why not put that movement to good use? Instead of killing birds, I’ll kill two drones with one stone, by embarking on a journey with the Ohio River. I can write, with eyewitness testimony, about how bad ecocide has become in the Ohio River basin. At the same time, I can ask the Ohio River if her waters can quell this despair burning within me.

I know I am not alone in my despair.

William Styron wrote in his poignant exploration of despair, Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness: “The pain of severe depression is quite unimaginable to those who have not suffered it, and it kills in many in stances because its anguish can no longer be borne. The prevention of many suicides will continue to be hindered until there is general awareness of the nature of this pain.”

As I travel with the Ohio River, witnessing her many wounds, I will describe my pain. If she will help me bear that pain, I hope my story will show how a river can save your life.

Will Falk is the author of How Dams Fall: On Representing the Colorado River in the First-Ever American Lawsuit Seeking Rights for a Major Ecosystem. He is a practicing rights of Nature attorney and a member of DGR.

Photo by Melissa Troutman.

by DGR News Service | May 3, 2020 | Listening to the Land

In A Language Older Than Words, author Derrick Jensen explores the relationship between silencing and clearcutting, between abuse of human beings and abuse of salmon, and offers us a different way to listen. This passage is taken from the opening of the book.

By Derrick Jensen

There is a language older by far and deeper than words. It is the language of bodies, of body on body, wind on snow, rain on trees, wave on stone. It is the language of dream, gesture, symbol, memory. We have forgotten this language. We do not even remember that it exists.

In order for us to maintain our way of living, we must, in a broad sense, tell lies to each other, and especially to ourselves. It is not necessary that the lies be particularly believable. The lies act as barriers to truth. These barriers to truth are necessary because without them many deplorable acts would become impossibilities. Truth must at all costs be avoided. When we do allow self-evident truths to percolate past our defences and into our consciousness, they are treated like so many hand grenades rolling across the dance floor of an improbably macabre party.

We try to stay out of harm’s way, afraid they will go off, shatter our delusions, and leave us exposed to what we have done to the world and to ourselves, exposed as the hollow people we have become. And so we avoid these truths, these self-evident truths, and continue the dance of world destruction.

As is true for most children, when I was young I heard the world speak.

Stars sang. Stones had preferences. Trees had bad days. Toads held lively discussions, crowed over a good day’s catch. Like static on a radio, schooling and other forms of socialization began to interfere with my perception of the animate world, and for a number of years I almost believed that only humans spoke.

The gap between what I experienced and what I almost believed confused me deeply. It wasn’t until later that I began to understand the personal, political, social, ecological, and economic implications of living in a silenced world.

The silencing is central to the workings of our culture.

The staunch refusal to hear the voices of those we exploit is crucial to our domination of them. Religion, science, philosophy, politics, education, psychology, medicine, literature, linguistics, and art have all been pressed into service as tools to rationalize the silencing and degradation of women, children, other races, other cultures, the natural world and its members, our emotions, our consciences, our experiences, and our cultural and personal histories.

Derrick Jensen is a long time environmental campaigner, activist, writer and founding member of Deep Green Resistance. He has published Endgame, The Culture of Make Believe, A Language Older than Words, and many other books.

Featured image by Max Wilbert.

![[The Ohio River Speaks] Can a River Save Your Life?](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2020/06/Can-A-River-Save-Your-Life.jpg)