by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 6, 2013 | Climate Change

By Daniel Whittingstall / Deep Green Resistance Vancouver

The Situation and Our Options

Increased concentrations of atmospheric greenhouse gases (GHG), primarily carbon dioxide emitted from the burning of fossil fuels for cheap energy, have driven global average temperatures to rise. While this in itself is cause for concern, the real distressing predicament lies within the many positive feedbacks that are at or near their tipping points.

One major positive feedback is the arctic permafrost where large amounts of methane (a greenhouse gas) are stored underground. If the temperature continues to rise from the current 0.8C up to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels the permafrost will hit a tipping point and melt, releasing roughly 1,000 giga-tones of methane (which is 22 times more potent a greenhouse gas than C02 over a 100 yr. period, and 150 times more potent over a period of a couple years) into the atmosphere.

Since the global temperature is currently being raised due to Industrial Civilization’s increase of these GHG’s, and there is a time-lag between temperature rise and GHG levels (temperature catching up to where these gases have set the bar, roughly a 30 yr. time-lag), then all we need to do to find out how close we are to this tipping point is to look at current and historic levels of GHG’s and the correlating temperatures, right? Come walk with me for a moment.

Current C02 levels are at 395 ppm (C02 being the main factor in the last 180 yrs. of forcing temperature rise, most of which has increased in the past 30 yrs.). The last time C02 levels were this high was roughly 15 million years ago (mya), with temperatures roughly 3-6C above current levels (or 4-7C above pre-industrial times). It would be good to note here that projected emissions and C02 levels by 2030, if “business as usual” continues, will be around 516-774 ppm; levels closer to those of the Eocene 54-50 mya when temperatures were roughly 5-7C higher than today.

Since there is a time-lag between temperature rise and levels of C02 we can be certain that the temperature will rise 3-6C over the next 30 yrs. solely based on current levels of C02 alone. This of course would be the case without adding in any positive feedbacks like the melting of permafrost, arctic sea ice, ice caps, glaciers, ocean die offs due to acidification and rapid forest die offs due to drought/deforestation etc.

The thing is, the world has changed quite a bit in the last 15 myr. A lot more carbon, and other substances with the potential to turn into GHG’s, have been stored in the earths surface due to the resumption of glacial cycles (since 13 mya the earth has plummeted into glacial cycles-5 mya and rapid glacial cycles-2.5 mya), increasing the potential/possibility with which to warm the globe if they were ever to be fully released.

You see, the other tricky part about this time-lag is that if there was a huge spike in GHG’s over a shorter period of time, lets say 5-10 yrs. (which would definitely be the case if permafrost, ocean and forest die off positive feedbacks were to be pushed over their tipping points, thus releasing massive quantities of methane and C02), the global temperature rise would also increase at an exponential rate. Not to mention the fact that methane has a minute time-lag in comparison to C02.

So, a more realistic picture would be: current GHG levels will undeniably rise temperatures past the 1.5C mark in the next 10-15 yrs., pushing the permafrost over its tipping point and hurling it into a rapid positive feedback loop, drastically escalating the already exponential rate of global temperature rise. During (or even possibly before) this short process, every other positive feedback will come into play (this is because they are all just as sensitive to temperature and/or C02 increases as permafrost is) forcing the global temperature to rise beyond any conservatively or reasonably projected model.

What’s really concerning in all this is that the arctic sea ice, permafrost, glaciers and ice caps have already begun their near rapid melt, and we continue to increase our output of fossil fuel GHG emissions and deforest the earth. Does anyone know what more than a 5-7C temperature rise looks like? Near-term extinction for the majority of biological life, including humans. It means that almost all fresh and drinkable water will dry up. It means that the sea levels will rise by roughly 120 meters (394 ft). It means that the current levels of oxygen in the atmosphere right now will become so low that neither I nor you will be able to breath it. This is the part where most people start formulating rebuttals that usually include the word “alarmist!”. Well, if the bare facts of our current situation are not alarming then I would think we have an even bigger problem.

There are two distinct scenarios here that I feel need to be pointed out (most often they are not). The first one goes like this: if we keep destroying the Earth and continue down this path of “business as usual” then the biosphere will collapse and along with it the global economy and ultimately industrial civilization.

The other scenario goes like this: if the destruction perpetuated by industrial civilization is somehow halted, subsequently averting total biosphere collapse, then the global economy and industrial civilization will collapse.

Basically, in the next 10-15 yrs., it is unequivocal that either way the global economy and industrial civilization (all that we who are living within this structure know and rely on) will collapse.

Kind of makes the worry of a national economic recession seem like a bad joke. The question is then: which scenario would you prefer? The near extinction of all life on earth (including your own species), or the end of a really bad experiment in social organization that has almost, but not quite, destroyed the planet?

The only chance of survival is to immediately end the consumption of fossil fuels (on all levels and in every way, including well-intentioned “green-energy-solutions” that pump huge amounts of C02 into the atmosphere annually during set-up and production), and to quickly begin sequestering GHG’s from the atmosphere. Best way to end this consumption would be to shut down all fossil fuel extractions, and to lock up all ready-to-be-used fossil fuels: gasoline, coal, stored natural gas, and throw away the key. Best way to sequester the GHG’s (semi-naturally) would be to plant native-to-bioregional plants/trees wherever they had been destroyed, and to grow our own food locally in the parks, on roadways, on rooftops, and on the front/back lawns of every suburban home.

These are our only two options, and we need to do both at the same time. Realistically this means we will need to bring down atmospheric C02 levels to where they were in pre-industrial times. In order to have any certainty of success we must be 50% of the way there by about 2016, and 100% there by 2020.

Yes, things look bad. But it all depends on your perspective. One good thing is that civilization does not represent the whole of humanity, nor does it represent any other species of life on earth. So, on the one hand it doesn’t look too good for civilization if people decide to rise up and end this insanity (which would subsequently be a positive effect on the biosphere and the rest of humanity). But, on the other hand, well…not so good for anyone.

Nevertheless be encouraged, we still have a small window of time in which to succeed!

Overview of Data

Below are dates with projected increases of both C02 and global temperature, along with projected tipping points for major positive feedback loops around the world.

Reasonable Estimation of Temperature Correlation With C02 Levels

These calculations are based only on current levels of C02 and historic corresponding

temperature level values, no future increase of C02, no current or future positive feedbacks.

Current level of C02 395 ppm = 4.5C increase above current temp, average between 3-6C

(2013, 0.8C).

35 year time-lag = 2048 at 4.5C increase

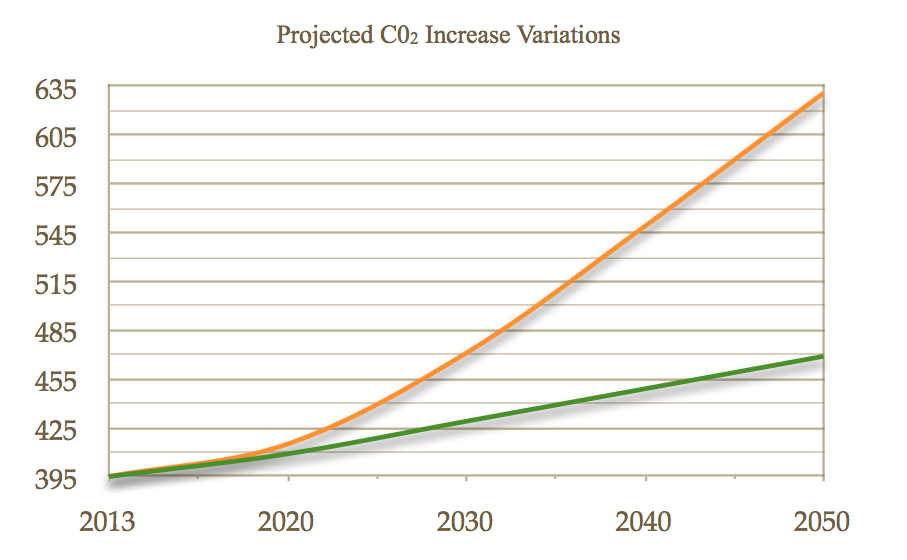

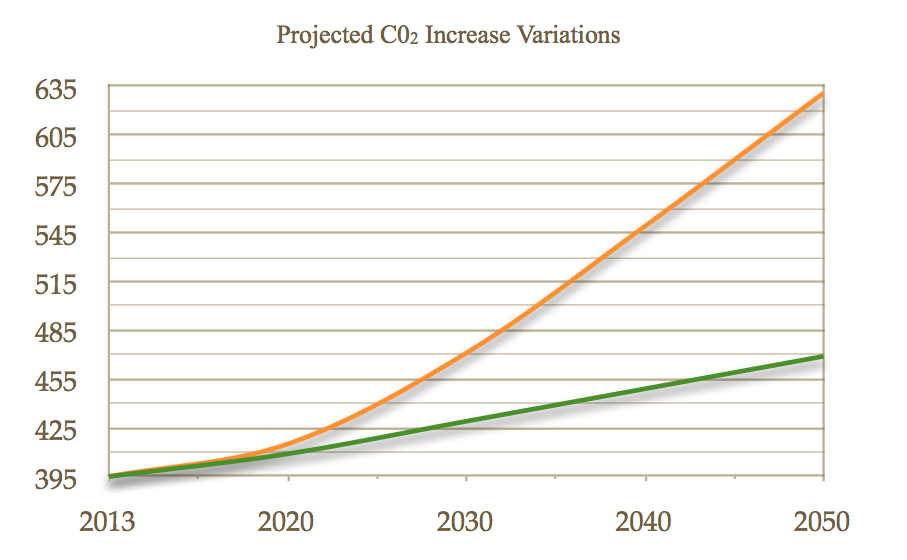

Estimates For C02 Increase

C02 ppm increase at current rate, five year increments

| 2013 |

2018 |

2023 |

2028 |

2033 |

2038 |

2043 |

| 395 |

405 |

415 |

425 |

435 |

445 |

455 |

C02 ppm increase at current rate with increase of fossil fuel consumption and positive feedbacks

| 2013 |

2018 |

2023 |

2028 |

2033 |

2038 |

2043 |

| 395 |

415 |

435 |

455 |

495 |

535 |

575 |

Estimates For Temperature Increase

Temperature based on current trends over past 20 years (without further inputs)

| 2013 |

2020 |

2030 |

2040 |

2050 |

2060 |

| 0.80 |

0.90 |

1.05 |

1.20 |

1.35 |

1.50 |

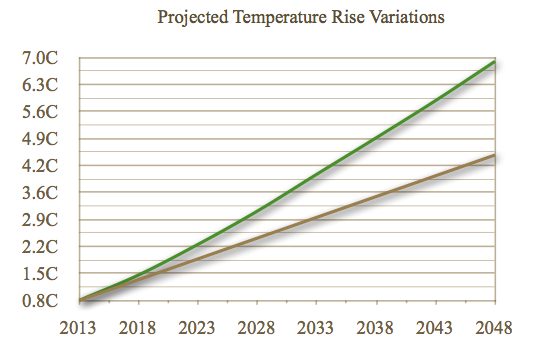

Temperature increase based on C02 correlation/35 year time lag

| 2013 |

2018 |

2023 |

2028 |

2033 |

2038 |

2043 |

2048 |

| 0.80 |

1.33 |

1.86 |

2.39 |

2.92 |

3.45 |

3.98 |

4.51 |

Temperature increase based on C02 correlation and forcing from positive feedbacks

| 2013 |

2018 |

2023 |

2028 |

2033 |

2038 |

2043 |

2048 |

| 0.80 |

1.45 |

2.23 |

3.04 |

4.06 |

4.88 |

5.90 |

6.90 |

Note:

2050 Conservative estimates based on current trends for major tipping points

2018 Reasonable estimates based on C02 and positive feedbacks for major tipping points

2034 Average between both estimates for major tipping points

Individual Tipping Points for Positive Feedbacks

2016 1.11C increase -Arctic sea ice tipping point (warmer oceans)

2018 1.33C increase -Arctic clathrate tipping point (methane release)

2019 1.43C increase -Greenland and Antarctic ice sheet tipping points (sea level rise)

2020 1.54C increase -Permafrost tipping point (methane release)

2028 455ppm C02 -Ocean acidification tipping point (C02 release)

Fig. 1. This shows the variations between projected increases in temperature: bottom line (brown) represents the rate of temperature increase based on the C02 correlation with a 35 year time lag, and top line (green) represents the temperature increase with C02 correlation including forcing from positive feedbacks.

Overview of Concepts in Climate Change

Carbon Dioxide

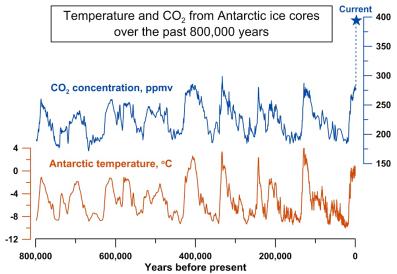

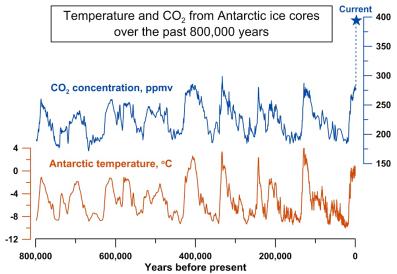

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a naturally occurring chemical compound and is a gas at standard temperature/pressure. CO2 exists in Earth’s atmosphere as part of the carbon cycle, emitted through plant and animal respiration, fermentation of liquids, volcanic eruptions as well as various other means. Levels of CO2 concentrations have risen and fallen over the past 3 billion years but with striking clockwork over the last 800 thousand years, rising and falling on a cycle of 40-100 thousand years (Fig. 2).

Ice core data indicate that CO2 levels varied within a range of 180 to 300 ppm over the last 650 thousand years (Solomon et al. 2007; Petit et al. 1999), corresponding with fluctuations from glacial and interglacial periods, with the last interglacial period nearing levels of 290 ppm (Fischer et al., 1999).

Fig. 2. This is a record of atmospheric CO2 levels over the last 800,000 years from Antarctic ice cores (blue line), and a reconstruction of temperature based on hydrogen isotopes found in the ice (orange line). Concentrations of CO2 in 2012, at 392 parts per million (ppm), from the Mauna Loa Observatory are shown by the blue star at the top (Simple Climate, 2012. Credit to: Jeremy Shakun/Harvard University). https://simpleclimate.wordpress.com/2012/04/04/global-view-answers-ice-age-co2-puzzle/

Near the end of the Last Glacial period, around 13,000 years ago, CO2 levels rose from about 180 ppm to about 260 ppm and leveled off until the Industrial Revolution in the mid 1700’s when it began to climb from 280 ppm (Neftel et al. 1985). While that 260 ppm of CO2 had remained more or less unchanged for the last 10,000 years, roughly since early Civilization, it was the actions of Civilization through the burning of fossil fuels, since the Industrial Revolution, that caused a dramatic increase over the last century (Blunden et al. 2012, S130).

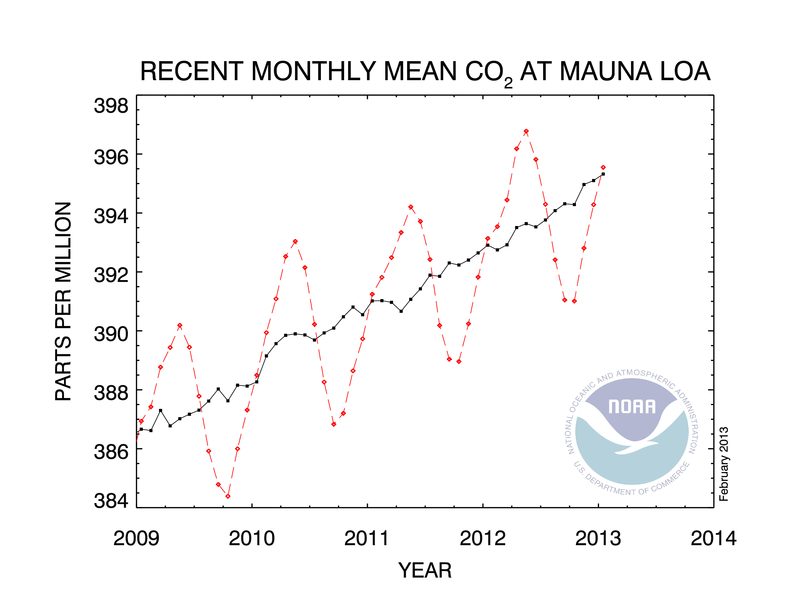

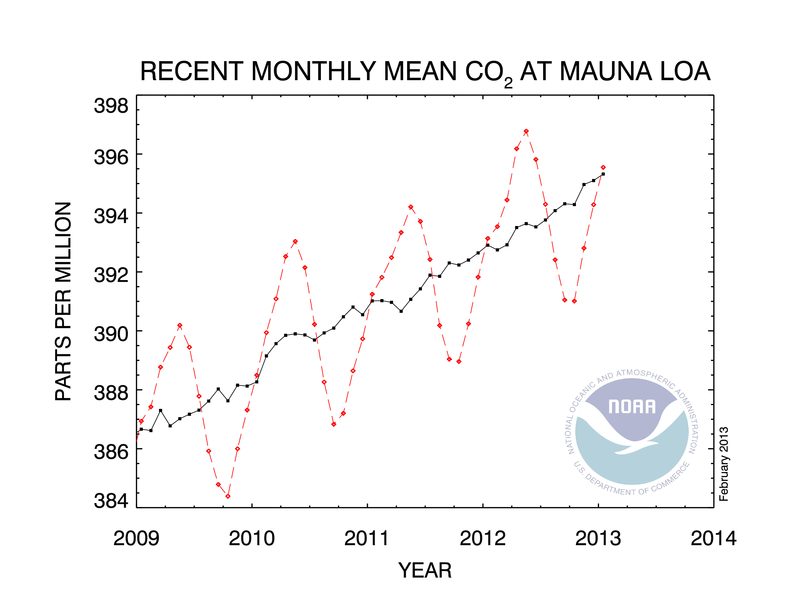

The contribution of Industrial Civilization’s CO2 comes mainly from the combustion of fossil fuels in cars, factories and from the production of electricity and deforestation for timber and agricultural lands. Today the monthly mean concentration levels, (Fig. 3), are around 394 ppm (Recent CO2 readings for 2012 at the Mauna Loa Observatory by the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration), increasing about 100 ppm from pre-industrial times in just the last 100 years and currently rising at a rate of 2 ppm each year.

Fig. 3. This table shows monthly mean CO2 measurements for the years 2008 to 2012 from the Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii. The dashed red line represents monthly mean values, and the black line is representative of monthly mean values with the correction for average seasonal cycles (NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory, 2012). http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/#mlo_full

Carbon dioxide has a long lifespan once emitted into the atmosphere. “About half of a CO2 pulse to the atmosphere is removed over a time scale of 30 years; a further 30% is removed within a few centuries; and the remaining 20% will typically stay in the atmosphere for many thousands of years.” (Solomon et al. 2007).

Therefore, the amount of CO2 currently in the atmosphere will possibly be persisting long enough to mingle with future emissions that are projected to be higher. Based on CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels in the year 2000, the IPCC calculated out the possible future increase of emissions if Civilization continued at that current rate of economic and consumer growth (increased fossil fuel consumption). “The projected emissions of energy-related CO2 in 2030 are 40–110 % higher than in 2000” (Solomon et al. 2007).

This could result in an increase of atmospheric CO2 from levels that were 369 ppm at the time, to 516-774 ppm by 2030 (Fig. 4); levels closer to those of the Eocene, 700-900 ppm roughly 54-50 million years ago (Paul N. Pearson 2000), when temperatures were about 5-7 degrees Celsius warmer than today and sea levels were roughly 120 m higher (Sluijs et al. 2008).

Fig. 4. This table shows the variations between projected C02 increases: bottom line (green) is the current rate of increase at 2ppm/yr. based on previous ten year average, top line (orange) is current rate plus increased Industrial Civilization forcing and positive feedbacks.

Greenhouse Earth

The environmental effects of carbon dioxide are of significant interest. Earth is suitable for life due to its atmosphere that works like a greenhouse. A fairly constant amount of sunlight strikes the planet with roughly 30 percent being reflected away by clouds and ice/snow cover, leaving the uncovered continents, oceans and atmosphere to absorb the remaining 70 percent. Similar to a thermostat, this global control system is set by the amount of solar energy retained by Earth’s atmosphere, allowing enough sunlight to be absorbed by land and water and transforming it into heat, which is then released from the planet’s surface and back into the air as infrared radiation.

Just as in the glass ceiling and walls of a greenhouse, atmospheric gasses, most importantly carbon dioxide, water vapor and methane, trap a fair amount of this released heat in the lower atmosphere then return some of it to the surface. This allows a relatively warm climate where plants, animals and other organisms can exist. Without this natural process the average global temperature would be around -18 degrees Celsius; see more (Solomon et al. 2007).

The current levels of greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations, principally carbon dioxide (Fig. 3), in the Earth’s atmosphere today are higher and have the potential to trap far more radiative heat than has been experienced within the last 15 million years (Tripati 2009), amplifying the greenhouse effect and raising temperatures worldwide. “The total CO2 equivalent (CO2-eq) concentration of all long-lived GHG’s is currently estimated to be about 455 ppm CO2-eq” (Solomon et al. 2007), as of 2005. These other contributors of GHG’s include methane released from landfills, agriculture (especially from the digestive systems of grazing animals), nitrous oxide from fertilizers, gases used for refrigeration and industrial processes, the loss of forests that would otherwise store CO2, and from the melting of permafrost in the arctic.

According to the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report “These gases accumulate in the atmosphere, causing concentrations to increase with time. Significant increases in all of these gases have occurred in the industrial era”, and the increases have all been attributed to Industrial Civilization’s activities (Solomon et al. 2007).

Historically, through the rise and fall of temperatures over the last 800 thousand years, temperatures have risen first, then CO2 would increase, accelerating even more temperature rise until a maximum when both would then drop, creating a glacial period. Though CO2 levels over this period of time have not been the trigger for temperature rise and interglacial periods, they either have occurred at the same time or have led positive feedback global warming during the stages of deglaciation, greatly amplifying climate variations and increasing the global warming capacity due to the greenhouse effect (Shakun et al. 2012), (Solomon et al. 2007).

What makes the present situation unpredictable to some extent is that never before has CO2 climbed so rapidly and so high, far ahead of temperature. Furthermore, this extra heat-trapping gas released into the atmosphere takes time to build up to its full effect, this is due to the delaying effect of the oceans as they catch up with the temperature of the atmosphere; deep bodies of water take longer to warm. There is a twenty-five to thirty-five year time lag between CO2 being released into the atmosphere and its full heat-increasing potential taking effect.

This means that most of the increase of global temperature rise observed thus far has not been caused by current levels of carbon dioxide but by levels that already have been in the atmosphere before the 1980’s. What is troublesome here is that these last three decades since then have seen the levels of greenhouse gases increase dramatically. On top of the current temperature rise we see now there is already

roughly another thirty years of accelerated warming built into the climate system.

There are many other Civilizational factors that contribute to this global rise in temperature outside of GHG’s. While these extra factors do supply further warming and are just as serious a threat to a semi-stable climate, they are not as long lasting.

One of the most notable of these, being the second largest Civilizational contributor to global temperature rise, is black carbon (BC), also called soot (T. C. Bond et al 2013). The greatest sources of BC are the incomplete burning of biomass (forest and savanna burning for agricultural expansion) and unfiltered diesel exhaust for transportation and industrial uses (Ramanathan and Carmichael 2008). There is a two fold warming effect from the BC.

First, the dark particles of this soot absorb incoming heat from solar radiation and directly heat the surrounding air, though only for a short period of time. Secondly, the soot particles in the air, once carried from their point of origin, are increasingly falling on snow and ice changing these reflective surfaces into absorptive ones, decreasing the albedo (reflectivity). Therefore, BC deposits have increased the melting rate of snow and ice.The most alarming of these effects can be seen on glaciers, ice sheets and the arctic sea ice (T. C. Bond et al 2013). While reductions in BC would have immediate but not long lasting effects on temperature rise, it would increase the chances of averting further warming

Nevertheless, the projected rise due to the continued increase in levels of GHG’s will not be prevented without

reducing overall emissions.

Temperature

The Earth is warming and this time the trend is far from natural. The average temperature of the Earth’s surface has risen by 0.8 degrees Celsius since the late 1800s (Fig. 4). On a geologic timescale this swift increase is alarming. When temperatures have risen in the past, warming the planet at several points between ice ages, the average length of time this process has taken is roughly 5,000 years to increase global temperatures by 5 degrees.

In this past century alone the temperature has risen ten times the average rate of ice age recovery warming, a recent trend not only driven by the rise of atmospheric CO2 concentrations, but also amplified by them.

Fig. 4. This table shows global temperature anomaly from 1880 through to 2011. Black lines are representative of annual mean variances and the red line is representative of five year running temperature mean’s. (NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, 2012) http://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/2011/Fig2.gif

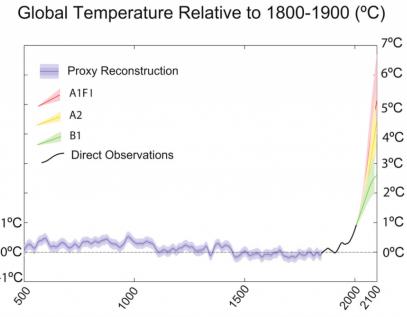

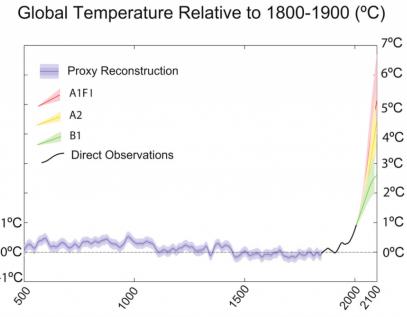

Continued economic, global population and energy consumption growth over the next few decades will consequently increase not only CO2 emissions, but also the rate and quantity with which they accumulate in the atmosphere. This is a business-as-usual scenario where efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, namely CO2, have fallen short of any earnest mitigation, “locking in climate change at a scale that would profoundly and adversely affect all of human Civilization and all of the world’s major ecosystems” (Allison et al. 2009); see scenario A1FI (Fig. 5).

Even if the global mean temperature only rises another 2 degrees before the end of this century, it would be a larger increase in temperature rise than any century-long trend in the last 10,000 years. A one degree global temperature rise is also significant for the reason that it takes a vast amount of heat to warm all the oceans, atmosphere, and land by that much; even more so is the significance of subsequent ecosystem collapse in climate sensitive areas such as the Arctic due to such a rise.

Fig. 5. This is a reconstruction of global average temperatures relative to 1800-1900 (blue), observed global average temperatures since 1880 to 2000 (black), and projected global average temperatures out to 2100 within three scenarios (green, yellow and red), (Allison et al. 2009). Scenario A1FI, adopted from the IPCC AR4 2007 report, represents projections for a continued global economic growth trend, and a continued aggressive exploitation of fossil fuels; the FI stands for “fossil fuel intensive”. http://www.ccrc.unsw.edu.au/Copenhagen/Copenhagen_Diagnosis_HIGH.pdf

Arctic Warming

The greatest changes in temperature over the last hundred years has been in the northern hemisphere, where they have risen 0.5 degrees Celsius higher since 1880 than in the southern hemisphere (Fig. 6). The Arctic is experiencing the fastest rate of warming as its reflective covering of ice and snow shrinks and even more in sensitive polar regions.

One of the main facets that are being affected by the increase of temperature in the Arctic is the potential collapse of Arctic ecosystems that succeed in the region. Ecosystems that are under pressure and that are at their tipping points can be defined as having their thresholds forced beyond what they can cope with. Different components of ecosystems experience diverse changes. In this instance,

“ecosystem tipping features” refers to the components of the ecosystem that show critical transitions when experiencing abrupt change (Duarte et al. 2012).

Fig. 6. This table shows both annual and five year mean temperature variances between 1880 and 2011. Temperature mean averages for the northern hemisphere are in red and southern hemisphere averages are in blue (NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, 2012). http://data.giss.nasa.gov/gistemp/graphs_v3/Fig.A3.gif

Sea Ice Loss

The significance of sea ice loss in the Arctic relates to a serious tipping point in the Arctic marine ecosystem which is given by the temperature at which water changes state from solid to liquid. Ice responds suddenly to changes at this temperature. This causes warming and loss of sea ice to amplify the potential changes to the climate including a reduction in albedo with the declining sea ice. Crossing the tipping point sets in motion many changes that further increases temperature in the Arctic region on top of current global warming (Duarte et al. 2012).

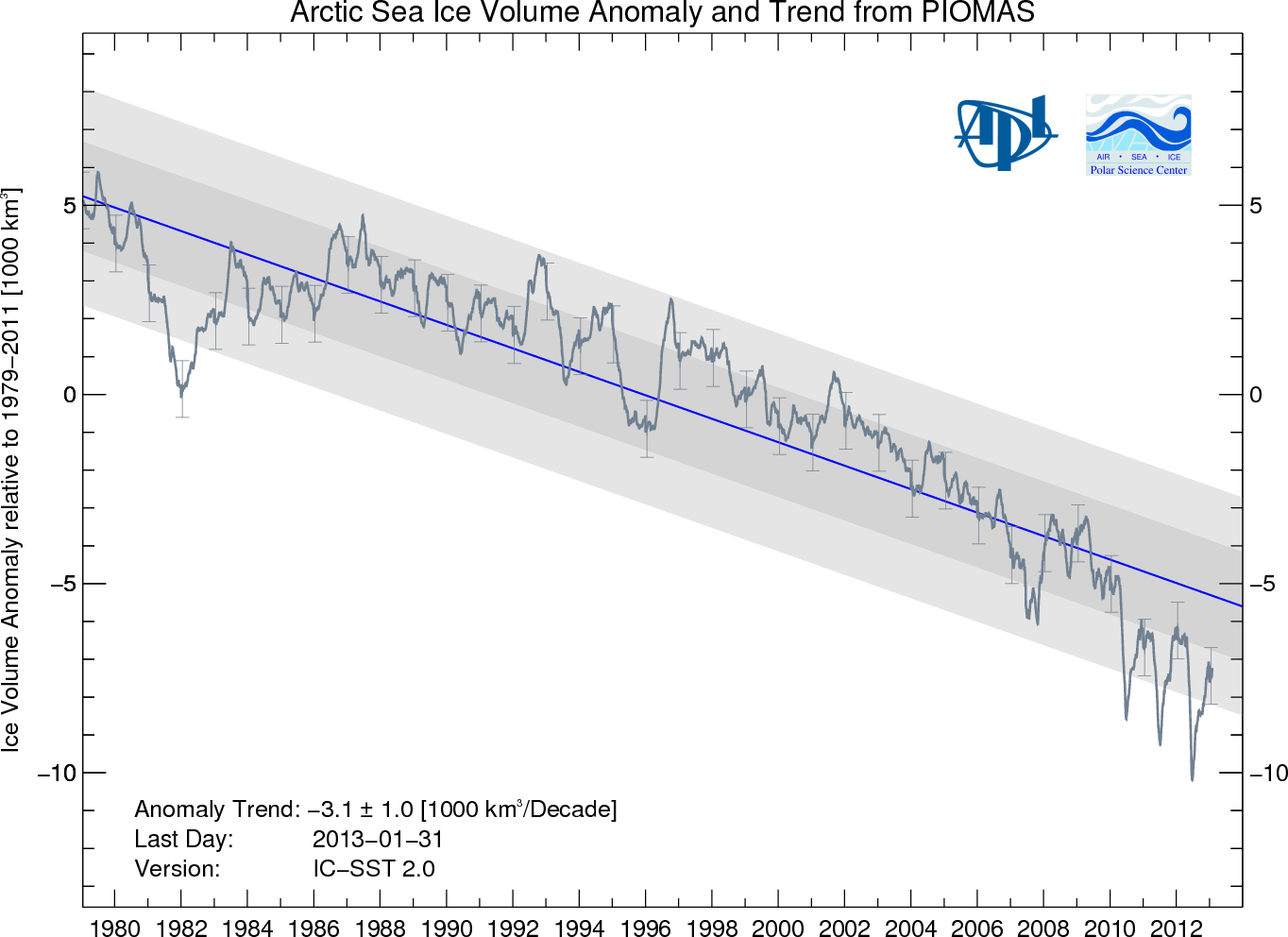

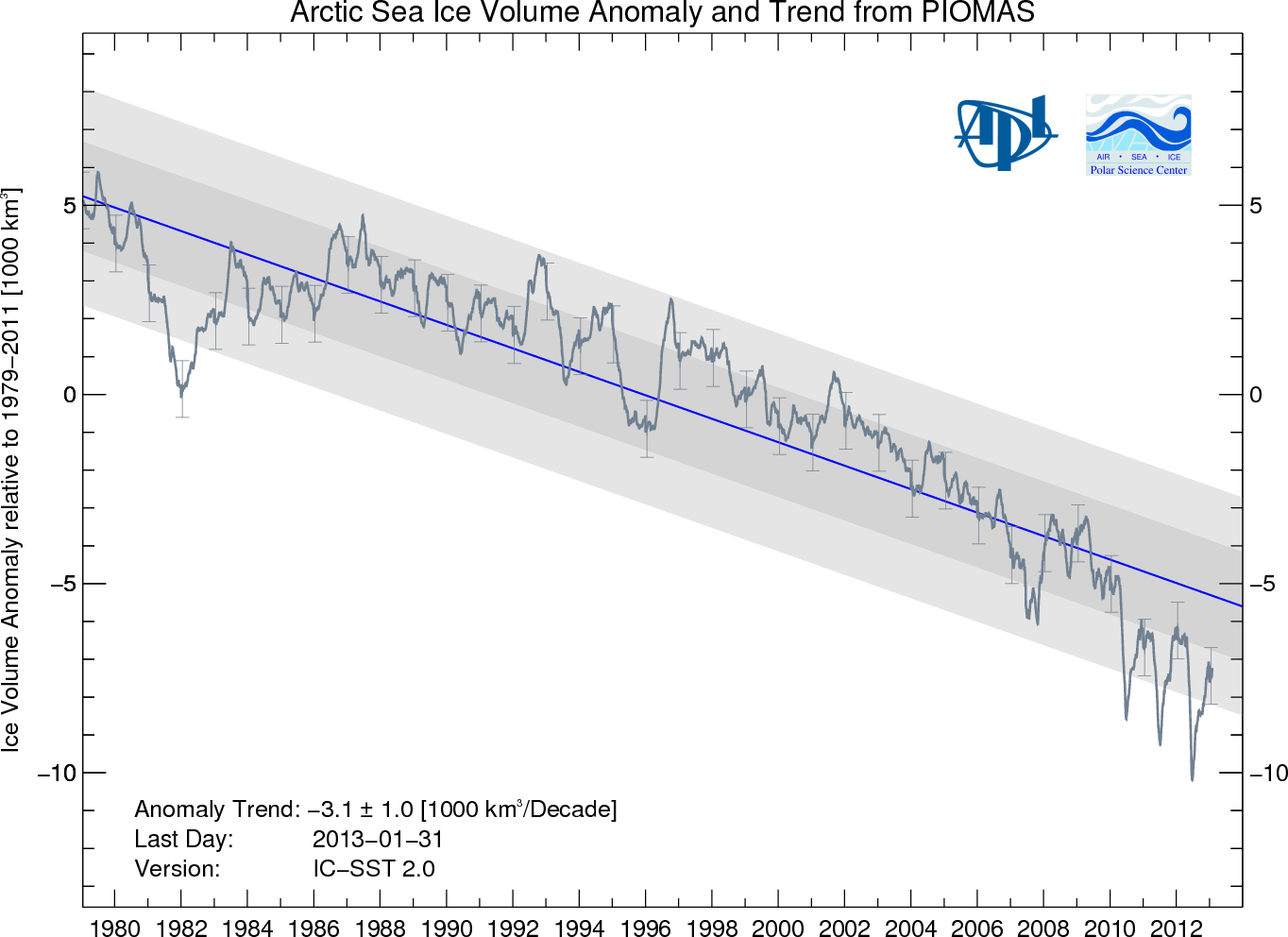

The ice that encompasses the Arctic has slowly been dwindling ever since a catastrophic collapse in the Arctic region in 2007. Since that point, close to two thirds of the ice has vanished compared to a decade earlier when the loss of sea ice was significantly smaller (Anderson, 2009). Scientists had previously predicted that the ice in the Arctic region would not be reduced to the point that it reached in 2007 until at least 2050, and in 2012 it dropped to levels much lower than in 2007 (Fig. 7). It is now predicted that the Arctic summer ice could disappear entirely as early as 2013.

The vulnerable setting of the Arctic region has certainly made it easy for global warming to have significant influences on the natural climate processes. The white ice naturally reflects sunlight back into space, but with the melting of the ice and subsequent open, dark sea water, the reflectivity is reduced and therefore the heat is retained instead. The arctic seas warm up, melting more ice, and then even more is absorbed and melted by the increasing water temperature change. This creates a dangerous feedback loop that intensifies melting and overall temperatures.

Observations and climate models are in agreement that through the 21st century, Arctic sea ice extent will continue to decline in response to fossil fuels being burnt and greenhouse gases being released into the atmosphere. Through the influxes of heat being circulated, temperature for the terrestrial and aquatic systems continues to increase, delaying ice growth during winter and autumn only to increase the temperature on the region.

Fig. 7. This table shows the ice volume anomalies of the Arctic ocean, with respect to the volume of ice over a period between 1979 to 2011. (Polar Science Center, psc.apl.washington.edu. 2011) http://psc.apl.washington.edu/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/schweiger/ice_volume/BPIOMASIceVolumeAnomalyCurrentV2.png?%3C%3Fphp+echo+time%28%29

Permafrost Melt

One of the most worrisome scenarios of a positive feedback is the thawing of huge quantities of organic material locked in frozen soil beneath Arctic landscapes. Vast quantities of carbon and methane from once rotting vegetation are stored in the frozen soil. This frozen soil is called permafrost and it contains significantly more carbon than is currently in the atmosphere.

Permafrost is defined as subsurface Earth materials remaining below 0°C for two consecutive years. It is thoroughly widespread in the Northern Hemisphere where permafrost regions occupy 22% of the land surface (Schuur et al. 2008).

The temperature, thickness and geographic continuity of permafrost are controlled by the surface energy balance. Permafrost thickness geographically ranges from 1 meter to 1450 meters depending on where the permafrost is situated. The layer that thaws in the summer and refreezes in the winter is referred to as the active layer. The thickness of the active layer ranges between 10 centimeters and 2 meters. Beneath the active layer is the transition zone, the buffer between the active layer and the more stable permafrost. The thickness of the active layer is significant because it influences plant rooting depth, hydrological processes, and the quantity of organic soil matter uncovered to the above-freezing seasonal temperatures. The growing concern is that permafrost’s relationship with the Arctic warming could lead to drastic changes for the region.

The processes that involve the transfer of stored carbon into the atmosphere have the potential to significantly increase climate warming in the Arctic region (Schuur et al. 2008). Since it only would take a few more degrees in temperature rise to tip the permafrost into rapid thawing and subsequently release huge amounts of stored carbon and methane, methane being over 20x as potent a greenhouse gas, this would result in a much larger feedback into the global GHG level rise.

A Warmer World

Industrial Civilization is on a path to heat the Earth up by 4 to 7 degrees Celsius before the middle of this century if it fails to end its carbon emissions, triggering a cascade of cataclysmic changes that will include the increase of extreme heat-waves, prolonged droughts, intensified weather patterns, the total loss of Arctic sea ice, rapid decline in global food availability, sea level rise affecting billions of people, and eventually an abrupt extinction of the majority of biological life on earth.

The solution, while not a simple one to execute, is clear: Industrial Civilization must end its reliance on fossil fuels and begin to sequester CO2 from the atmosphere immediately, reducing the atmospheric concentration of CO2 down to a safe level.

A full reference list for this article is available here: http://dgrnewsservice.org/newsservice/2013/03/reference-material1.pdf

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 10, 2013 | Colonialism & Conquest, Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis

The following speech was given as part of the Warrior Up Resistance Tour in January 2013.

Good evening friends, allies, relatives, I hope and pray that I say something tonight that makes you feel uncomfortable. You cannot live in these times—in the thrashing endgame of industrial Civilization, in the thrashing endgame of industrial capitalism, in the thrashing endgame of the so-called American empire—without feeling at least somewhat uncomfortable.

I am part of the radical environmental movement Deep Green Resistance. Our goal is gigantic in scope: “The goal of DGR is to deprive the rich of their ability to steal from the poor and the powerful of their ability to destroy the planet.” We believe lifestyle and consumer choices like recycling, taking shorter showers, or changing light bulbs, will not save us. We believe industrial civilization is destroying the planet and needs to be taken down and turned into rubble. The dams need to be taken out, the cell phone towers need to be knocked to the ground. We believe that, if a culture of resistance forms immediately, we all can help to soften the inevitable crash of this death culture. As a movement, we believe that when it comes to tactics and strategy, we need it all. We need aboveground actions, and we need underground actions. We need people willing to be on the frontlines and countless others supporting them with loyalty and material support. If you come from the occupying invader culture, it is your duty to put your body on the line in defense of Mother Earth and indigenous peoples. That is what makes a good ally.

The state of the planet where we live is this: Over 90% of the large fish in the oceans are gone. There is 10 times as much plastic in the oceans as there is phytoplankton, the small creatures that supply half the oxygen we breathe. 97% percent of native forests have been destroyed. 98% of native grasslands have been destroyed. The water in 89% of U.S. cities is contaminated with carcinogens. If you are under 30 years of age, half of you will get cancer at some point in your lifetime. In the last 24 hours, 200,000 acres of rainforest has been destroyed and 13 million tons of toxic chemicals have been released onto the Earth and into the water. Over 45,000 fellow human beings have died from starvation or lack of water, 38,000 of them children. Between 120-200 species went extinct today never to breathe life on this planet–that’s 73,000 a year. Indigenous cultures and languages are going extinct at an even faster relative rate.

As you know now this death culture is waging war on all life. This is a war and we need to say that. I say it again: this is a war. And I ask you: what the hell are you going to do about it? Those of us on the frontlines are willing to do what is necessary to save and defend the living by any means necessary. Are you willing to do the same?

One of my Lakota allies Chase Iron Eyes wrote: “We owe allegiance to the trees, the four leggeds, the winged ones, the water, the salmon, the buffalo, the deer, the elk, the moose, the caribou, the bears, the corn, the wild rice and all living things which find a way to live together. All of us are making a choice everyday about whether or not we will choose a better path or continue complacently down this path that leads to the death of the planet.”

Again I ask you: are you willing to do the same?

For far too many years, this invader culture has done its best to divide us. What we need desperately is solidarity—solidarity with life and standing in solidarity against this death culture. I stand here a proud traitor to this dominant culture of death and destruction.

Are you willing to say the same?

Where there is death and destruction, there is always life fighting to live; where there is oppression there is always resistance. Let’s be very straight forward and honest about fighting back. Our mother is being tortured right in front of our eyes. Our relatives are being killed and poisoned by this invader death culture. None of us can win this fight alone. We need each other, and it has always been done this way. We need each other and we need it all. Andrea Dworkin said, “I found it was better to fight, always no matter what.” Again I ask: are you willing to do the same? A lesson from her-story shows that it is in the best interest of life to fight back: the Jews that fought back against the Nazi during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising had a higher rate of survivability then those who just went along with the system of death that was in place. We must always fight back. Again I ask: are you willing to do the same?

Real resistance looks like MEND, the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta. The Niger Delta has been destroyed and poisoned by Royal Dutch Shell. The people of that land tried peacefully to petition their government for redress, and to ask that the land be cleaned up and that the bodies of their families not be poisoned. Instead of listening to the people, the military government hung 8 of the leaders of the peaceful nonviolent movement, including Ken Saro Wiwa. After that happened, more than 200 brave human beings took up arms to protect the people and the land. They masked their faces, and wore camouflage clothing, the colors of Earth’s Army. They have sabotaged oil equipment and kidnapped oil workers. They have said to Royal Dutch Shell, “Leave our land while you can or die in it.” Again I ask: are you willing to do the same?

Trans-Canada thinks they will be building a pipeline through my Lakota allies’ territory. I stand before you today unafraid when I say this will happen over my dead body. Only over my diead body will they poison the water, and poison countless children and countless generations. Again I ask you: are you willing to do the same?

I leave you with a quote by author and activist Derrick Jensen: “We need all the courage of which the human heart is capable, forged into both weapon and shield to defend what is left of this planet. And the lifeblood of courage is, of course, love…The songbirds and salmon need your heart, no matter how weary, because even a broken heart is still made of love. They need your heart because they are disappearing, slipping into that longest night of extinction . . . . We will have to build the resistance from whatever comes to hand: whispers and prayers, history and dreams, from our bravest words and braver actions. It will be hard there will be a cost, and in too many dawns it will seem impossible. But we will have to do it anyway.”

This is a war!

Join us!

Thank you.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 23, 2013 | Strategy & Analysis

By Alex Rose / Deep Green Resistance Colorado

We’re up against a lot. With hundreds of species going extinct every day, with the oceans being vacuumed of life, with the last vestiges of wild forests being felled or burned and the heart of the planet being torn up to poison the air, civilization is driving Earth towards biotic collapse. We can’t afford to waste time or energy with so much at stake; dismantling the society that is dismantling the planet is no easy task.

For more than 30 years now, the environmental movement has been working toward that end, yet in few (if any) circumstances have we been able to seriously dislodge the foundations of industrialism. Despite our best efforts, the species count continues to decline as the carbon continues to rise. Those we’re up against are well protected and have immense resources at hand to protect themselves from disruption.

Systems of power—such as patriarchy, white supremacy, capitalism, civilization—safeguard themselves through brute force. They react with overwhelming violence against those who oppose them. However, this isn’t the only tool available to those in power, and rarely is it the first to which they reach when they feel threatened. One of the more sinister and effective techniques is systemic misdirection.

Oppressive and destructive systems protect themselves first and foremost through disguise and deception. They hide their weaknesses and vulnerabilities, coaxing us into attacking dummy targets or symbols of their power, rather than the material structures that support their power. The results are ones we’re all familiar with (or should be): we focus our attention on specific symptoms of the problem rather than the underlying causes, and our efforts for political change are diffuse and uncoordinated, challenging only particular manifestations of larger oppressive power systems, rather than the systems themselves. We wander into a strategic dead-end, and energy is redirected into the system itself.

We are guided into a strategic dead-end, and our energy is redirected to bolster the system itself.

Breaking free of this misdirection-dynamic requires a thorough lifting-back of the veil that’s been draped over our eyes. It means focusing our efforts where they will be most effective, targeting critical nodes and bottlenecks within industrial systems to bring civilization down upon itself.

We need critical and strategic processes of target selection. One powerful tool towards this end is the CARVER Matrix. CARVER is an analytic formula used by militaries and security corporations for the selection of targets (and the identification of weak points). “CARVER” is an acronym for six different criteria: criticality, accessibility, recuperability, vulnerability, effect, and recognizability.

Criticality is an assessment of target value and is the primary consideration in CARVER and target selection. A target is critical if destruction, damage or disruption has significant impact on the operation of an entity; or more bluntly, ‘how important is this target to enemy operations?” Different targets can be critical to different systems in different ways: physically (as in interstate transmission lines), economically (such as a stock exchange), politically, socially, etc.

It’s important to remember that nothing exists in a vacuum; society is made up of inter-related entities and institutions, and our targets will be as well. Thus the criticality of a potential target should be considered in the context of the way that target relates to larger systems. For example, there are thousands of electrical transmission substations all over the world, and hence they may initially seem non-critical. However, some substations carry a much greater load than others and are systemic bottlenecks, whose disabling would have ripple effects across entire regions. Criticality depends on several factors, including:

- Time: How rapidly will the impact of the attack affect operations?

- Quality: What percentage of output, production, or service will be curtailed by the attack?

- Relativity: What will be affected in the systems of which the target is a component?

Accessibility refers to how feasible it is to reach the target with sufficient people and resources to accomplish the goal. What sorts of barriers or deterrents are in place, and how easily they can be overcome? Accessibility includes not only reaching a target, but the ability to get away as well.

Recuperability is a measure of how quickly the damage done to a target will be repaired, replaced or bypassed. Just about anything can be replaced or rebuilt, but some particular things are much more difficult, such as electrical transformers, few of which are manufactured in the U.S. and which take months to produce.

The fourth selection factor is vulnerability. Targets are vulnerable if one has the means to successfully damage, disable, or destroy them. In determining vulnerability, it’s important to compare the scale of what is necessary to disable the target to the capability of the “attacking element” to do so. For example, while an unguarded dam might seem a vulnerable target, if resisters had no means of bringing it down, it wouldn’t be considered vulnerable. Specifically, vulnerability depends on the nature & construction of the target, the amount & quality of damage required to disable it, and the available assets (personnel, funds, equipment, weapons, motivation, expertise, etc.).

Next is effect. Effect considers the secondary and tertiary implications of attacking a target, including political, economic, social, and psychological effects. Put another way, this could be rephrased as “consider all the consequences of your actions.” How will those in power respond? How will the general populace respond? How will this affect future efforts?

Last is recognizability; will the attack be recognized as such, or might it be attributed to other factors (e.g. “It wasn’t arsonists that burned down the facility, it was an electrical fire”). Depending on the particular circumstances, this can cut either way; taking credit for an attack can bolster support and bring more attention to an issue, but it may also make actionists more vulnerable to repression. Recognizability also applies at a more individual level: were fingerprints or other evidence left at the site of the target through which the identity of the attackers can be determined?

Often, numerical values between 1 and 10 are given to each of the target selection criteria in the CARVER Matrix, and then totaled for each potential target. More generally, CARVER presents a critical framework for strategic planning and decision-making, helping us to avoid misdirected action.

It needs to be said that this sort of critical and calculated approach to resistance efforts applies to nonviolent & aboveground groups and operations as well as those that are militant or underground. Nonviolent resistance is too often distorted to fit romanticized ideas of a moral high ground, and is relegated to pure symbolism. But struggle (whether violent or nonviolent) isn’t about symbolic resistance; it’s about facing down the reality of power, identifying its lynchpins, and using force to disable or break them. The particular tactics we use determine the form the force will be applied in, but unless we identify and target the critical lynchpins, the daily destruction wrought upon the earth will continue unabated as we strike at the distractions dangled before us.

For too long our movements have fallen prey to poor target selection or misdirection. When we’re not too busy fighting defensive battles, we focus our energies on those entities which are either entirely non-critical to the function of industrialism or are invulnerable given our capacity for action. And the world burns while we spin our wheels.

In our next Time is Short bulletin, we will take a closer look at several examples of different actions, applying this analytical examination to better understand the importance and relevance of target selection in radical movements.

The forces we’re up against are ruthless and calculated; they’ll do whatever they can to keep us ineffective, and when that fails, they bring down all the repressive force of which they’re capable. If we’re to be successful in stopping industrial civilization, we’ll have to identify and undermine its critical support systems. We don’t have much time, which is why we can’t afford to waste it on actions, targets or strategies that don’t move us tangibly closer to our goals.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a biweekly bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 2, 2013 | Strategy & Analysis

Within the radical environmental movement, it is widely acknowledged and rightly accepted that we have little time left before the earth is driven into catastrophic and runaway biotic collapse. We know that civilization is predicated on the slow dismemberment of the planet’s life support systems—a dismemberment that is increasing in speed as more efficient and devastating technologies are developed. We know that for a healthy, living world to survive, industrial civilization cannot.

It is also acknowledged (although perhaps less widely) that we are incredibly outnumbered and outgunned, so to speak. People aren’t exactly lining up around the block to join the movement, and when was the last time any of our campaigns weren’t starved for funds? We don’t have many people or resources at our disposal, and if we’re honest with ourselves, we know that isn’t changing anytime soon.

Due to these limitations, which should be glaringly (if dishearteningly) obvious to anyone involved with radical organizations or movements, we need to take extra care in devising how we chose to allocate the energy and resources we do have. With so much at stake and so little time to muster decisive action, we cannot afford to put time and effort into strategies and actions that are ineffective.

Additionally, in devising our strategies and tactics, we need to accommodate those personnel and resource limitations: a strategy that requires more people or more resources (or both) than are actually available to us is a recipe for quick failure. As obvious as this should be, these sorts of strategic considerations seem to be mysteriously absent from the radical movement*.

Of course, simply because these conversations aren’t happening doesn’t mean that there isn’t an unspoken strategy, a framework within which we operate by default. While this may not be articulated explicitly, our actions form a collective strategic template.

By and large, the strategy of the environmental movement is one of attrition, a slow battle with the goal of wearing down the institutions & forces of environmental degradation until they cease to function. Whether by default or perceived lack of alternatives, this has been accepted as an unquestioned strategy for the overwhelming majority of those of us in the environmental movement. This is a mistake which could cost us the planet if not revisited and corrected.

A strategy of attrition is one in which you wear down an opponent’s resources, personnel, and will to fight to the point of collapse. As a strategy, it intends one of two outcomes: through the continual depletion of the aforementioned resources, the enemy suffers unacceptable losses and surrenders or capitulates out of hopelessness; or, the enemy is worn down over time to the point that it is incapable of function and operation.

One classic example of attrition and exhaustion strategy being implemented is that of Ulysses Grant’s campaign against the Confederacy in the later part of the American Civil War. Grant attacked and pushed the Confederate army continuously, despite horrific losses, with the theory that the greater manpower and resources of the Union would overwhelm the Confederacy—which would prove correct.

In the context of the modern environmental movement, this strategy looks only slightly different.

Again, there is no articulated grand strategy within the environmental movement—whether we’re talking about the entire spectrum or just the radical side of things, there is no defined plan for success. However, our work, campaigns, initiatives and actions fit rather snugly into the box of attrition strategy: we focus on one atrocity at a time—one timber sale, one power plant, one pipeline, one copper mine—doing our best to eliminate one threat at a time. These targets aren’t selected based on their criticality or importance to the function of civilization or industrialism, but are selected by what might be best described as reactionary opportunism.

And that makes sense: remember we’re vastly outweighed in every way imaginable by those in power, and time is quickly running out. With 200 species going extinct every day, the sense of urgency that drives us to try and win any victory we can is understandable and compelling.

Unfortunately, this mix of passion and earnestness has led the environmental movement into a strategic netherworld. If our goal is to stop the destruction of the planet, we would do well to turn a critical eye toward the systems that are responsible for that destruction, identify the lynchpins within them, and organize to disable and destroy them.

Instead, we wander blindly in every which direction, striking out wildly, hoping that enough of our glancing blows find a target to wear the systems down to the point of collapse. But this strategy fails to account for the power & resource imbalance between “us” and “them”, as well as the time frame for action.

To address the first shortcoming: those in power—those who benefit from and drive industrial extraction & production—have near limitless resources at their disposal to pursue their sadistic goals, whereas things look decidedly different for those of us who fight for life. Every day, millions—billions—of humans go to work within the industrial economy, and in doing so, wage war against the planet. Those of us on the other side of the war don’t have—and can’t compete with—that kind of loyalty or support. China is still building one new coal-fired power plant every week, and worldwide, coal plants are being erected “left and right”1.

How many coal plants did we shut down this week? The week prior?

For a strategy of attrition to be viable or effective, we need to be disrupting, dismantling or retiring industrial infrastructure as quickly or quicker than it can be constructed and repaired. At this point, we’re lucky if we can stop new projects, new developments, new strip mines, timber-harvest-plans, oil & gas fields, etc., much less drawdown those already in operation.

This is true across the whole spectrum of activism and the environmental movement. On the more liberal side of things for example, take Bill McKibben and 350.org’s newest campaign, an initiative to get universities, cites, and churches/synagogues/mosques to divest from fossil fuel companies. The idea is essentially to slowly bleed money away from the fossil fuel industry, modeled after the divestment campaigns of the anti-apartheid movement. Unfortunately, the fossil fuel industry isn’t exactly hurting for investors, and it certainly isn’t reliant upon money from university endowment funds for its survival. Equally problematic, industrial civilization requires fossil fuels to function, and hence these companies already have the support and subsidies of governments around the world—do we think they’ll suddenly abandon their undying support for these companies? And besides, a slow drain on their stock prices must be balanced against the record profits being made in the industry: do we really think that this outweighs the capital available to the industry?

The same is true of many of the most radical actions taken in defense of earth, such as that of the Earth Liberation Front (ELF). Their first (and arguably primary) goal was/is “To cause maximum economic damage to a given entity that is profiting off the destruction of the natural environment.”2 That’s great, and there’s certainly nothing wrong with causing maximum economic damage to those that profit from the degradation of the earth, in and of itself. But what is the realistic extent of “maximum economic damage”, and what is the capacity of those entities to absorb it? For example, although the ELF claims to have caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage, every year companies lose more than that due to employees playing fantasy football at work. Absurdities of industrial capitalism aside, the point should be clear; the capacity of our movement to effect significant change through compounded economic damage is severely outweighed by the damage the system does to itself, and also by its ability to absorb that damage.

All of which is to say that 200 species went extinct today, and there hasn’t been a single peer-reviewed study put out in the last 30 years that showed a living system not in decline: for us to be satisfied with slightly diminished industry profits or anything less than a complete end to the death machine of industrial civilization is unconscionable.

None of this is to say that 350.org or the ELF aren’t worthwhile organizations who’ve done good things. This is not a critique of those groups in particular, because countless other organizations share the same strategic flaws; it’s a critique of the movement as a whole that continues to produces the same strategic inadequacies.

And then there’s the second problem presented by an attrition model: time. Attrition affects the greatest damage over a long period of time. Unfortunately, we don’t have much time. As previously mentioned, 200 species vanish into the endless night of extinction every day; 90 percent of large ocean fish are gone, the old growth forests are gone, the prairies and grasslands are gone, the wetlands and riparian areas are gone, the clean freshwater is gone. Every year, the predictions put out by climatologists and modelers are more severe, and every year they say the previous year’s predictions were underestimates. The Energy Information Administration says we have five years to stop the proliferation of fossil fuel infrastructure if we are to avoid runaway climate change (and some say this is overly optimistic)3. If we had decades or centuries in which to slowly erode and turn the tide against industrialism, then perhaps we could consider a strategy of attrition. But we don’t have that time.

To reiterate, this isn’t a strategic model that holds any real hope for the earth.

Smart strategic planning starts with an honest assessment of the time, people, and resources available to our cause, and moves forward within those constraints. We don’t have much time at all; the priority at this point is to bring down civilization as quickly as possible. We don’t have many people either, and can’t realistically expect many to join us; the rewards and distractions—the bread and roses—provided in exchange for loyalty to the established systems of power mean we will always be few and that we will never persuade the majority. Finally, our resources are also incredibly limited, and hence we need to focus on using them in ways that accrue the greatest lasting impact.

Given these limitations, it should be clear that a strategy of attrition is more than unwise; it’s fatal for both us and the rest of the planet. Working within the framework created by the available time, people and resources, and with the goal of physically dismantling the key infrastructure of civilization, the strategy with the greatest chance of success is one of targeted militant strikes against key industrial bottlenecks. As opposed to the slow grind of attrition, this would be a quick series of attacks at decisive locations; rather than waiting for the building to be eroded away by wind and rain, collapse the structural supports of the building itself; we would opt instead for a strategy of decisive ecological warefare.

Many of us put all the energy and passion we have into our work, and dedicate our lives to the struggle. But that won’t be enough. We’re up against a globalized death machine that is skinning the planet alive and cooking the remains; we will never be successful if we put our efforts into trying to dent their profit margins. Burning SUVs and vandalizing billboards have an important role to play in developing a serious culture of resistance (as does organizing students), but we can’t afford to pretend those sorts actions are meaningful or threatening blows to the industrial superstructure.

Time is short. If we’re to be effective, we need to move beyond half thought-out strategies of attrition that try to compete with the resources of those in power. We need to devise strategies that use the resources available to decisively disable and dismantle the infrastructures that enable their destruction and power.

*This isn’t to say that there is no strategic thinking, planning, or action at all; many organizations are very smart and savvy in undertaking specific actions and campaigns. The issue isn’t a lack of strategy in particular situations or campaigns, but comprehensively of the entire environmental movement as a whole.

1. “China & India Are Building 4 New Coal Power Plants—Every Week.

2. “Earth Liberation Front”. http://www.earthliberationfront.tk/

3. “World headed for irreversible climate change in five years, EIA warms”. http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2011/nov/09/fossil-fuel-infrastructure-climate-change

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a biweekly bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 1, 2012 | Human Supremacy

By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

I’ll tell you, if there is one instinct

I just can’t get with at all

It’s the urge to kill something beautiful

Just to hang it on your wall

—Ani DiFranco

Mangled. Squished flat. The sides of roads are littered with the bodies of unexpecting mothers, brothers, fathers, sisters, nieces, nephews, lovers, and friends. There is nothing but callous disregard in the speeding hunks of metal that hurl down the highway. Lost forever are the stolen lives of too many raccoons, mice, snakes, birds, opossums, skunks, deer, and lizards. Add to this to the unthinkable toll of bees, moths, caterpillars, ants and others whose small bodies are barely noticed unless they are being scraped from a windshield.

The same callous disregard tortures 9 billion animals every year in factory farms around the world. Can you imagine being locked in a filthy cage with so many other bodies that you can’t even turn around or lie down? Can you imagine having your throat slit while you are still conscious? Can you imagine being plunged into scalding-hot water while your body is skinned or hacked apart while you are still conscious? This is the daily reality for so many cows, calves, pigs, chickens, ducks, and geese whose lives are as important to them as ours are to us.

The same callous disregard tortures tens of millions animals every year in vivisection labs on college campuses and research facilities around the world. Can you imagine being dissected, infected, injected, gassed, burned and blinded by doctors? Can you imagine if this was justified as “important research” for the purpose of testing the safety of make-up and dish soap? This is the daily reality for so many primates, dogs, cats, rabbits, and rodents whose lives are as important to them as ours are to us.

The same callous disregard is responsible for other atrocities: poaching (we’ve all seen the pictures of baby seals being clubbed), deep sea trawling (90% of large fish have been decimated), and the turning of whole habitats into buildings or fields of agriculture (the North American Prairie, once home to millions of bison, is now 2% of its original size).

Most of us in industrial society can go through our days relatively shielded from the real processes of life. And many of us are shielded too from the reality of suffering that this way of life—industrial civilization—forces so many nonhumans to endure. This, combined with the war on empathy perpetrated by the dominant culture, makes it easy for most people to ignore the suffering or dismiss it as something insignificant. How many times have you heard it said that other animals simply cannot feel as much or in the same ways as human beings can? You’ve seen the pain yourself; it was clear in the eyes of the furred and feathered as they slipped away from this world as surely as any human being. But the ruling religion of this culture is human supremacy (however, you may also call it Christianity or Science). And human supremacy demands that you are wrong, that your empathy is but misplaced and silly.

Roadkill is more difficult to ignore. There they lay; not behind the doors of a slaughterhouse or vivisection lab, nor in the remote regions of the oceans and forests. On the sides of the roads, they are murdered, left motionless with a frightened look on a deformed face, guts spilling from the chest. Not so different from you, really. I mean, let’s say it’s you who lives in the forest; the one which roads now slice through like so many knives. You crossed the road for hunting early in the day, but now you want to come home. As you step from the soil onto the pavement, you are swimming in thoughts of your loved ones, your resting place, your life waiting for you just steps ahead. But you never make it there. No. In a flash, your body is torn from its path, destined now only to rot on the road’s shoulder. There you lay.

Within the clumps of mangled fur and feathers is a history, a family, a community, a wisdom, a life more rich and beautiful than most any vehicular passerby cares to pay a thought to.

Industrial capitalism functions by devaluing life. It couldn’t survive any other way. The system is based on production, a euphemism for the transformation of living creatures into dead commodities. Mountaintops become soda cans. Old-growth forests become 2x4s. Alligators become handbags.

If the dominant narrative fails to see, or more likely actively ignores, the sacredness of life, then roadkill isn’t a subject worth a moment’s consideration. It’s just part of having roads and cars, the narrative says, as if roads are more real than living, breathing creatures, as if any human being is entitled to decide the fate of whole other populations. Can we not imagine living without roads and cars, but so easily accelerate towards a future without the two hundred species of plants and animals that go extinct every day?

I want to ask how someone can simply not grieve death. But, then I’d have to ask how a whole culture has been built on the systematic destruction of the place it relies on. There is no rational answer for a phenomenon so insane.

In his book, Columbus and Other Cannibals, Jack Forbes argues that the death urge of the dominant culture can only be truly explained as a very real disease, one which he calls the wetiko (or cannibal) psychosis. This disease, Forbes says, is the “greatest epidemic sickness known to [humans].” He goes on, “Imperialists, rapists, and exploiters are not just people who have strayed down a wrong path. They are insane (unclean) in the true sense of that word. They are mentally ill and, tragically, the form of soul-sickness that they carry is catching.” The sadism of torturing nonhumans is a perfect example of the wetiko. Those who run factory farms and vivisection labs carry the disease and spread it throughout the culture until it seems just part of life.

Experiencing the sight of roadkill was a major step in my own reclamation of the empathy that is my birthright as a human animal. It helped to kick-start the decolonization of my heart and mind, the endless process of rooting out the wetiko sickness from my being. The injustice is just too glaring to ignore. I remember distinctly one day when I was sitting in the passenger seat of a car and I spotted up ahead a dead raccoon in the middle of the road. A half-mile up the road were her two children, also dead. My heart burned, instinctively. Were those tears in my eyes?

Since then, I’ve seen the flames of so much life needlessly extinguished. It never ceases to hurt, nor to motivate a spirit of resistance.

Here’s one story, this one from just the other day: I’m walking in the small forest near my home. From ten yards, I see the unmistakable white face of an opossum. She’s lying still on her side in the middle of the trail. I approach and see her glassy eyes looking straight ahead. I’ve heard of opossums “playing dead,” whereby they may feign death for up to four hours when scared. But, I’m pretty sure that this one is truly dead. This is affirmed when I return to the grave site a few days later.

I don’t know how this opossum died. There were no predator marks on the body, and the middle of a highly frequented trail seems a peculiar place to make a death bed. Something forced this situation. Maybe it’s the poisons put on lawns, or the fact that this half-acre of trees is surrounded on all sides by cars and roads and houses. Opossums are indigenous to this land and under assault as surely as indigenous human cultures are. In the native Powhatan language, opossum is derived from the word apasum, which means “white animal.” They’ve long been the largest population of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere. But now, civilization encroaches upon the homes of all nonhumans, and opossums, despite adapting as scavengers, now struggle against a massive decrease in food and habitat.

Inexperienced urbanite that I am, I don’t know what to do with the body. Should I just leave and let someone else deal with it? But, if not me, whoever finds the opossum will call animal control services to dispose of the body, meaning it will ultimately end up in a landfill or incinerator. I know this creature would prefer to stay in the forest. Like all place-based beings, she would want to fulfill her sacred task of giving back her body to the land which has always given her the sustenance of life.

Pressed to move quickly enough to avoid the concern of trail-goers sure to show up at any moment, I contemplate my options. Seeing some large maple leaves on the forest floor, I have an idea. I stop to pick them up and, with a leaf covering each hand like a raggedy glove, I pick up the opossum. With a slight strain, I’m able to move her to the side of the trail. There, I pile leaves on top of her and make a small enclave around the mound with fallen branches. Here is a grave, however feeble my attempt.

After the opossum’s body was sufficiently hidden from human passerby, I was moved to say a few words of respect. In my exasperated state, I thought only to say something simple like, “rest easy, friend.”

The opossum deserved more. The passing of life into death deserves a deep respect and commemoration. There’s nothing so humbling. This is what is missing in the dominant culture, and what we all need to learn once again. If I could go back in time, and if I had the words, this is what I wish I had said.

Your life is not in vain. In all your time of living, you’ve contributed to the health and diversity of this place, and thus, to the health and diversity of the world. There are those of my species who not only fail to give back in this way, but actively destroy the world which gives them life. They are insane. They must be stopped. Your life, and all life, is sacred and infinitely more important than industrial civilization. I’m sorry that you had to live your final moments surrounded by this unnatural and immoral construct. I’m sorry that you did not get to properly say goodbye to this world. Your life is not in vain.

I’d like to extend my humble prayer to all victims of highways, factory farms, vivisection labs, and industrial extraction. Life requires death, but none so ruthless. This culture is a project sustained only by death. It thrives by never allowing the renewal of life. These are sadistic murders caused by human hubris rather than the natural deaths simply part of life.

I’ll say it again: Death is part of life. All beings go through the motions of being first predators, then prey. Everyone has to eat. Death is necessary to complete the cycle that renews life. That is, death in a world in balance. Industrial civilization, by design, ruins that balance. It preys not just on individuals, but on whole landbases, and not for the necessary sustenance required by living beings, but because it is driven by a death urge, by the wetiko psychosis.

And does it require saying that life wants to live? I know the people who think up vivisection and factory farms have become so deadened as to have forgotten this, or believe it true only when applied to humans (but even then, how alive can a human really be when daily life consists of being a torturer?). You, however, should know better. You should know that, as Derrick Jensen eloquently writes, “Life so completely wants to live. And to the degree that we ourselves are alive, and to the degree that we consider ourselves among and allied with the living, our task is clear: to help life live.”

Here’s another story. My friend saw a deer who was hit so hard that he flew into another oncoming car. The impact literally tore his legs from his body. And yet another story: A doe stood on the side of the road mourning the body of her friend who had just been struck. This is their land. The roads and this civilization are ever-expanding—it’s a war, plain and simple. Just look on the side of the road. You’ll see.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance.