by Boris Forkel / Deep Green Resistance Germany

Call me crazy, but I spent the last evening sitting in my garden and telling the first toad I met this year what I do and why. I told her about Deep Green Resistance, about the destruction of the natural world by our culture, and I asked her to tell me how she and her kind perceive all this.

I don’t know if I understood her correctly, but what I heard was: “Well, too many of us are dying. We know that some of you are trying to help us. That’s not enough. It has to stop.“

It doesn‘t matter if I‘m projecting or not. The toad is right.

She wasn’t shy, she sat quietly right next to me, moved a little bit every now and then and looked at me with beautiful red, serious eyes.

I do this regularly, I go to the wildest places that still exist here and listen to nature. I see different kinds of insects, wild bees, bumblebees, mosquitos, beetles, a few dragonflies. I see – mostly hear – birds, but I can only distinguish about five or six species. I love the call of the codger when it gets dark.

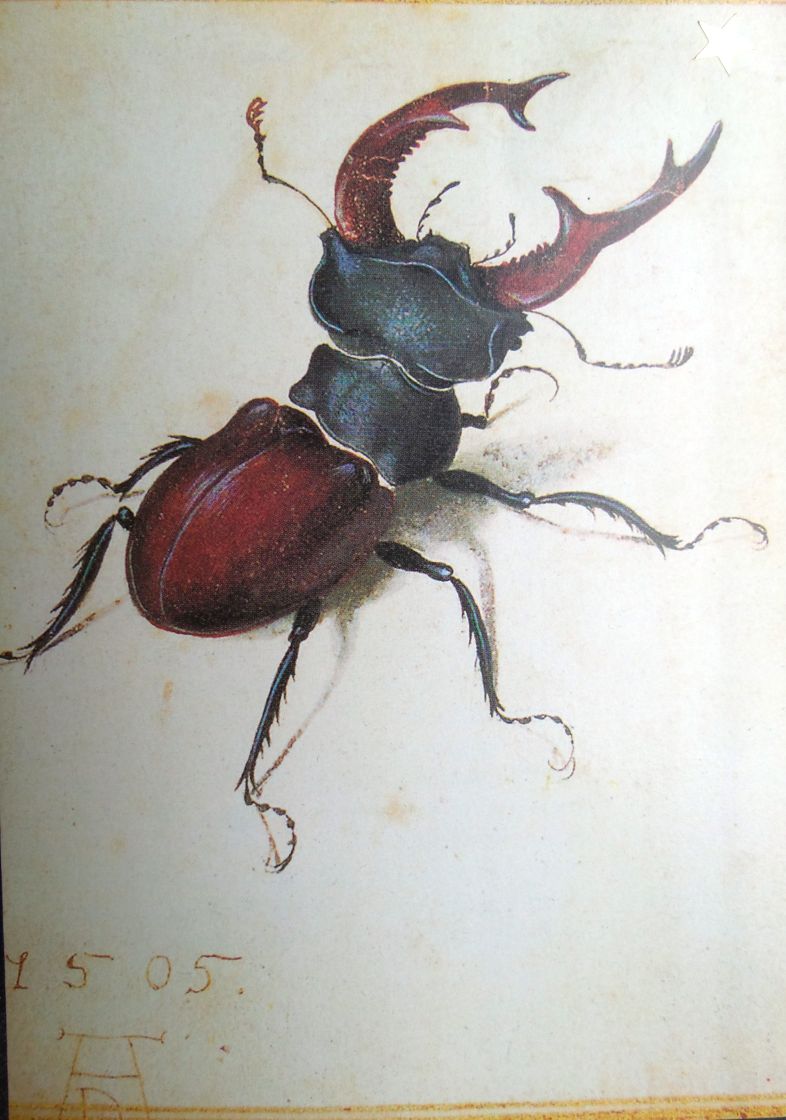

I know that the stag beetles come out of the ground at the beginning of June, where they have lived for three years as increasingly fattening grubs, to fly with a huge hum into the summer forest, where they will live exclusively from the sap of the rare old oaks their females prepare, since the males cannot bite the bark because of their huge antlers. Every June, I wait in my garden to welcome them. Towards the end of the summer they carry out their ecstatic fights and mating rituals, until after spending only three months as Europe‘s most giant beetles, they die and serve hungry birds as autumn delicacy.

I see squirrels, bats, toads, grass frogs and spotted salamanders. Sometimes I meet bigger animals: Wild boars, badgers, foxes, deer, but these are still scared of me and usually flee quickly.

The European bison, or wisent, that used to inhabit this forest, I only know from the zoo. But even the ones that are forced to live in captivity are gigantic, beautiful, trusting and kind. They look at me with loving eyes, each of them asking the same question:

Why?

Twice in my life I‘ve seen a snake. The first encounter was a European adder, many years ago in a village in the Odenwald (the forest where I live), when I was a school kid. The second one was a giant garter snake in my garden a few months ago. She (or he) was enjoying the sun, lying on a large oak tree that recently had been killed by a storm.

After this encounter, I wanted to learn more about them. I read that garter snakes used to be treated as house snakes and were considered holy animals that bring happiness and blessing. The garter snake was worshipped by numerous European peoples until the late Middle Ages, and appears in many myths. People fed garter snakes milk, just as the Indian villagers do in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book with their holy village cobra.

Today, you are very lucky if you see a garter snake once in your life.

It’s getting dark. I look at the stars and the full moon. I speak to them and all the animals, plants and living beings that surround me. I tell them what I do and why, and I say prayers. I declare my loyalty. I tell them that I am one of them, and that I will do everything in my power to help them. They’re my relatives.

I’m asking them to tell me the most important things I can do for them. I tell them that I love them.

The toad is still sitting next to me. She (or he) looks at me, lets me take a foto and politely waits until I’m done talking to her. Then she slowly trots towards the pond I have build for her kind to inhabit.

Like thousands of times before, I walk the way from my garden to my small apartment in the city. Like thousands of times before, I look down over the Neckar River to see Babylon. I fear Babylon. I’m terrified of Babylon.

The Neckar River once was called Germany’s wildest river, but it has been raped for at least 2000 years, since the Roman invaders drained parts of it to build the old bridge that is still in place today. Nowadays, the River essentially serves as a road for the many freighters that are desperately trying to satisfy the insatiable hunger of Babylon. Like the Rhine, it had been full of salmon in the past, but this was so long ago that no human people can remember. I’m sure the trees still know.

During the last two years beavers return, after being absent for about 150 years. There are supposed to be about three thousand of them again in Baden-Württemberg. The state government is considering to kill about half of them because they are allegedly damaging trees.

The natural world is full of wisdom. So often I‘ve sat here or there, listening, speaking, praying. The river, the forest and all the creatures who still live here spreak different languages and have different messages. They have taught me a lot, and I have a lot more to learn. But in one thing they all agree:

It has to stop. Babylon Apocalypse.

Awesome

Should have never left the garden.