Featured image: Maasai women on a conservation project in Kenya. Joan de la Malla, Author provided by Stephen Garnett, Charles Darwin University; Álvaro Fernández-Llamazares, University of Helsinki; Catherine Robinson, CSIRO; Erle C. Ellis, University of Maryland, Baltimore County; Hayley Geyle, Charles Darwin University; Ian Leiper, Charles Darwin University; James Watson, The University of Queensland; John E. Fa, Manchester Metropolitan University; Kerstin Zander, Charles Darwin University; Micha Victoria Jackson, The University of Queensland; Pernilla Malmer, Stockholm University; Tom Duncan, Charles Darwin University, and Zsolt Molnár, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest / The Conversation

Indigenous peoples have a deep and unique connection to the lands they inhabit. This connection has persisted throughout the world, despite centuries of colonisation, displacement and suppression of their cultural identities.

What has never been appreciated is the contemporary spatial extent of Indigenous influence – just how much of Earth’s surface do Indigenous peoples still own or manage?

Read more: Remote Indigenous communities are vital for our fragile ecosystems

Given that Indigenous peoples now make up less than 5% of the global population, you might imagine the answer to be “very little”. But you would be wrong.

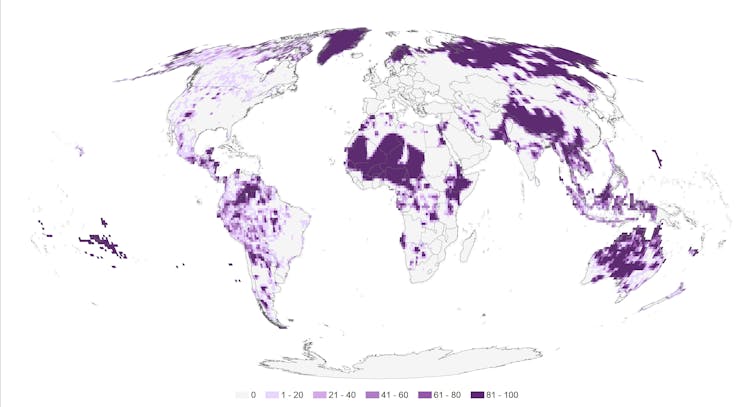

In our new research, published in Nature Sustainability, we mapped Indigenous lands throughout the world, country by country. We found that these covered 38 million square kilometres – about a quarter of all land outside Antarctica.

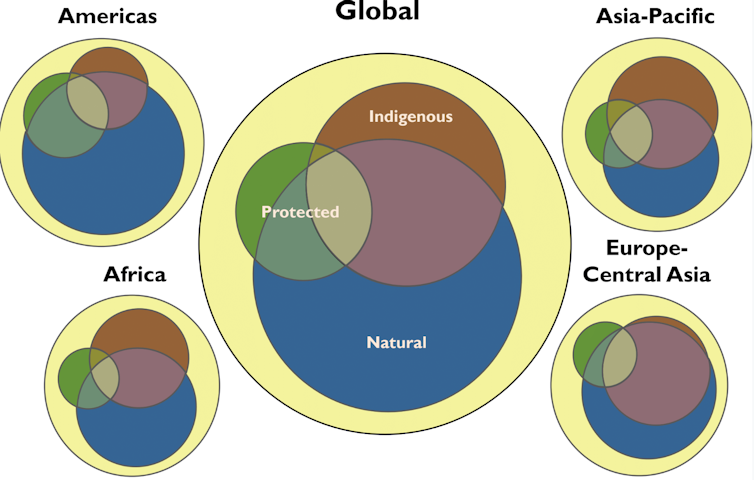

These areas are very valuable for conservation. About 65% of Indigenous lands have not been intensively developed, compared with 44% of other lands. Similarly, just 10% of the world’s urban areas, villages and non-remote croplands are on Indigenous peoples’ lands.

By contrast, Indigenous lands encompass nearly two-thirds of the world’s most remote and least-inhabited regions. These are the places with the lowest levels of built environments, crop land, pasture land, human population density, night-time lights, railways, roads and navigable waterways.

An incredible 40% of lands listed by national governments around the world as being managed for conservation are Indigenous lands. Some of this has official recognition. For instance, Australia would never meet its promises under the Convention on Biological Diversity if its Indigenous peoples had not been prepared to allocate more than 27 million hectares of their land to conservation.

A great contribution

This highlights the great contribution that Indigenous peoples are making to conservation. Many groups have instituted land-management regimes that are already delivering significant conservation benefits.

Yet there is danger in making assumptions about the aspirations of Indigenous peoples for managing their lands. Without proper consultation, conservation projects based on Indigenous stewardship may be unsuccessful at best and risk perpetuating colonial legacies at worst.

Conservation partnerships will only be successful if the rights, knowledge systems and practices of Indigenous peoples are fully acknowledged. Many Indigenous peoples have acknowledged this fact, by calling for partnerships that respect, understand and follow local processes. There is no one size that fits all – Indigenous peoples are hugely diverse.

Indeed, so important are local perspectives to Indigenous relationships with land that we pondered for a year on the ethics of creating a global map. However, we also felt that the story of enduring Indigenous influence needs to be told. Our final map shows that broad swathes of Asia, Africa, the Americas, Australia and the far north of Europe are Indigenous lands.

Our results are particularly important at this time when goals for sustainable development after 2020 are being developed. The results also feed into assessments by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the international body that assesses the health of the world’s wildlife diversity and ecosystems. It is much more than biodiversity that relies on Indigenous management of land. So too do many of the ecosystem services that allow humans to thrive.

Read more: Friday essay: caring for country and telling its stories

Finally, we should note that, for many countries, the areas we have mapped are the minimum – further work will almost certainly discover that Indigenous influence extends far further than is currently acknowledged.

Yet our crucial message remains the same: that Indigenous peoples hold the future of much of the world’s wilderness in their hands.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Beau Austin, Benjamin McGowan, Eduardo S. Brondizio and Neil Burgess to this article and the research that underpins it. Stephen Garnett, Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University; Álvaro Fernández-Llamazares, Researcher, University of Helsinki; Catherine Robinson, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO; Erle C. Ellis, Professor of Geography and Environmental Systems, University of Maryland, Baltimore County; Hayley Geyle, Research Assistant, Charles Darwin University; Ian Leiper, Geospatial Scientist, Charles Darwin University; James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland; John E. Fa, Professor of Biodiversity and Human Development, Manchester Metropolitan University; Kerstin Zander, Senior Research Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Micha Victoria Jackson, PhD candidate, The University of Queensland; Pernilla Malmer, Senior Advisor, Stockholm University; Tom Duncan, , Charles Darwin University, and Zsolt Molnár, Scientific Advisor, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Beau Austin, Benjamin McGowan, Eduardo S. Brondizio and Neil Burgess to this article and the research that underpins it. Stephen Garnett, Professor of Conservation and Sustainable Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University; Álvaro Fernández-Llamazares, Researcher, University of Helsinki; Catherine Robinson, Principal Research Scientist, CSIRO; Erle C. Ellis, Professor of Geography and Environmental Systems, University of Maryland, Baltimore County; Hayley Geyle, Research Assistant, Charles Darwin University; Ian Leiper, Geospatial Scientist, Charles Darwin University; James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland; John E. Fa, Professor of Biodiversity and Human Development, Manchester Metropolitan University; Kerstin Zander, Senior Research Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Micha Victoria Jackson, PhD candidate, The University of Queensland; Pernilla Malmer, Senior Advisor, Stockholm University; Tom Duncan, , Charles Darwin University, and Zsolt Molnár, Scientific Advisor, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.