Editor’s note: The following is the complete text of Larry Engelmann’s “The Woman Who Remembered Paradise,” which first appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, on July 10, 1988. The “Westerners,” whom the Spaniards called the “San Juan Indians,” are elsewhere identified as the Amah Mutsun people, who lived and hunted in what are today’s San Mateo, Santa Clara, Santa Cruz, Monterey, and San Benito Counties. Anyone who finds this article as moving as we do is encouraged to visit the Amah Mutsun website. The tribe’s statements about themselves, their past and their future are equally educational and moving, and make it clear that while Ascención Solórsano may have been the last person fluent in the Mutsun language, the tribe itself is far from dead. Further reading has confirmed that Popeloutchom was NOT in Santa Clara Valley, but in the Pajaro River valley, around the present day town of San Juan Bautista, in San Benito County, just northeast of Monterey. At that time, the tribe’s range was roughly from there to Santa Cruz, and was the reason for the establishment of the missions at San Juan Bautista and Santa Cruz. This article does, in some ways, reflects the prejudices and simplistic understandings of anthropologists and of civilized attitudes towards the indigenous. However, it nonetheless gives valuable insight in the life of indigenous people of what is now central California. Thank you to Mark Behrend for providing this article, and for the above research.

The Last San Juan Indian in Silicon Valley

By Larry Engelmann

Long, long ago, before Silicon Valley was settled and suburbanized, before it was leveled and developed, subdivided and paved, tract-homed and condoed, malled and gridlocked, and long before the air was browned and seasoned, the streams and well waters shellacked with chemical solvents, before it was high-teched and silicon-chipped, mainframed and PC’ed, before it was airported, theme-parked and fast-fooded, before the rude snorting of the first automobile shattered the pristine silence on the narrow rutted trails that passed through miles and miles of gorgeous orchards, before Leland Stanford built his university, before the silver mines were chiseled out of the hills or the missions constructed, before Sir Francis Drake peered from the deck of the Golden Hinde at the Golden Gate, long before any European ever heard the word America, another race of people inhabited the place we call Silicon Valley. They believed they were living in an earthly paradise. They called it Popeloutchom.

The people of Popeloutchom were gentle. As gentle, it was said, as the climate and the cool breezes that slipped over the mountains to the west and whispered through the fruit trees and caressed all the living things in the valley each evening. They believed this valley was the most beautiful place in the world.

Because of that conviction they had no desire at all to travel far and look upon what must surely be lesser lands given by the gods to lesser men. In this garden of Popeloutchom, where the air was clear and the water pure and the Earth naturally fruitful and abundant, they were happy.

When the first Franciscan missionaries arrived and told the stories of their God and the Eden he had created for his first man and woman, the people of Popeloutchom were fascinated and flattered. Obviously, they felt, the God of the Franciscans had once seen this valley, and had tried to copy it for his people far away.

The important difference, of course, between his Eden and this place was that no one had ever been expelled from this paradise. Here there was no evil serpent and no fall from grace, no paradise lost. Popeloutchom was paradise preserved. In the English translation of their own language – a language long since lost – the people of Popeloutchom called themselves “the Westerners,” because they were the westernmost group of several loosely related tribes. Over the years, though, they had lost contact with their Eastern cousins, who had simply melted away, like snow before the summer sun. Yet the gods had preserved and sustained the Westerners in Popeloutchom.

The Westerners were an indigenous people, who knew neither treachery nor deceit nor war. They welcomed the befuddled strangers who sometimes stumbled upon their settlements. Such lost travelers were regarded as honored guests who would, when treated warmly, tell unusual stories about distant places and strange gods, before moving on.

And so the Westerners welcomed the first white men who “discovered” their valley. Unlike earlier travelers, however, these intruders came to stay. They constructed missions, put up walls and worshiped the God who created Eden. And they brought with them also their deadly trinity of cholera, smallpox and measles. The Westerners, with no immunity to the European diseases, began to die by the hundreds. Those few who survived were brought within the discipline of the missions. They lost their old faith and their old lands. They were given a new name by the missionairies. They became the San Juans.

And gradually, like their Eastern relatives, they melted away.

Early in the twentieth century, when historians and ethnologists tried to record the story of the Westerners, they found that those gentle people of Popeloutchom had become extinct. And they concluded, after careful research, that sometime around 1850, the last member of that kindly and tolerant race had vanished.

It came, then, as a substantial surprise when word was relayed to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., in late 1929, that all of the Westerners had not died. There remained, in fact, a single surviving full-blooded member of that tribe. And she wanted the story of her life and of her people recorded for posterity.

John Harrington, the Smithsonian’s leading ethnologist, rushed to California in order to transcribe that final testament of this rare survivor of a lost race, this last Westerner.

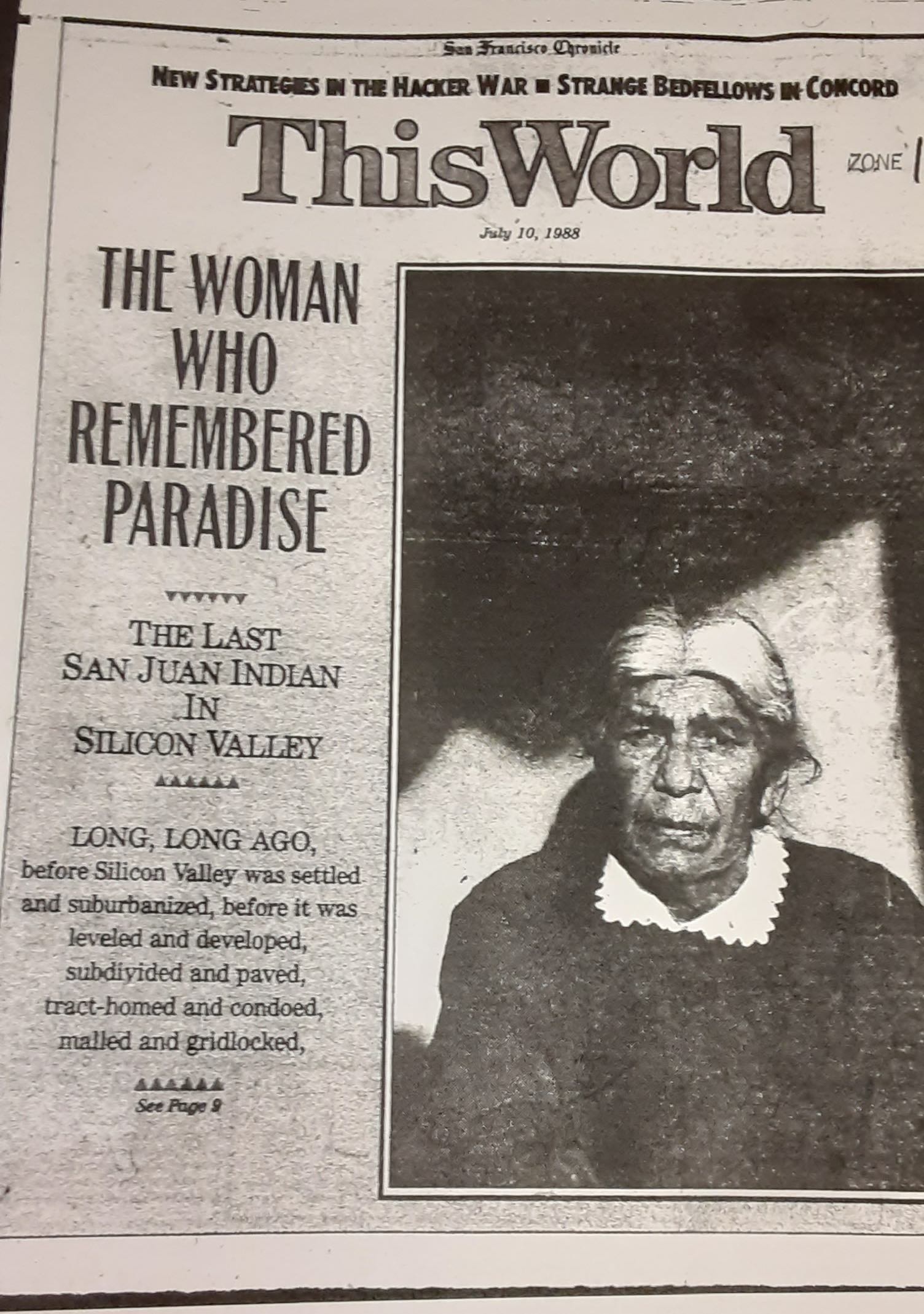

She called herself Ascención Solórsano, and for as long as anyone could remember, she had lived in Gilroy. There she was known, because of her curative powers, as a great and generous “doctora.” For several decades, the few remaining Indians of the region had known of the miracles performed by the doctora. Her wisdom, they believed, was the accumulation of learning of a hundred generations of Westerners.

Each day, the sick and the lame and the afflicted came to her from hundreds of miles away. They lined up in the doorway to her tiny house, and camped at night in her yard, transforming her property into a humble pastoral version of Lourdes. Inside, the doctora listened carefully to their tales of physical woe. Then she mixed tonics and ointments from local herbs and roots and dispensed them to the afflicted. It was rumored that the remedies of the doctora were always successful. She restored the health of anyone who sought her help. Those who could, paid for her miracles. Those who could not pay brought food or small articles of some value. And those who could pay with nothing material were reminded simply to remember the doctora in their prayers.

For many years the doctora tirelessly carried on her practice. The local press ignored her and the local authorities overlooked her. She practiced medicine without a license, to be sure. But those who were supposed to enforce laws forbidding such activities either never heard of her or never believed she existed. No complaints for malpractice were ever filed against the doctora.

Then, one night in the late summer of 1929, a light evening breeze whispered a prophetic message to the doctora. For all of her life, Ascención had read such portents and premonitory signs in the wind and rain, and in the lost language of the birds. She could read the messages from nature as easily as one today might read the headlines in a newspaper.

The wind told Ascención that she was going to die in three days. And so now at last the things that remained to be done must be done quickly.

She took out the black silk dress she had sewn years earlier to wear when she confronted death. She then said goodbye to her friends in Gilroy and went to the home of her daughter – who was half Indian – in Monterey. There, in her daughter’s tiny two-room frame house, she waited for death. A bed was set up in one room and several pillows were placed on it so that Ascención might sit up comfortably. Neighbors and friends were summoned to see her. And she shared with them all the stories and the collective memories of the Westerners. It was, she believed, the final gift of her lost race to the children of the despoilers of Popeloutchom.

Then, through her narrative, Ascención apparently assuaged the gods of the Westerners and aroused their compassion. As she spoke, day after day, her strength was restored and death was postponed.

When Harrington arrived from Washington, Ascención looked at him in silence for a long time. Then she pronounced her evaluation of the enthusiastic scholar. “You are a vehicle of God,” she said, “that comes to see me in the 11th hour to save my knowledge from being lost. I will teach you up to the last day that I can, and see if I can tell you all that I know.” This is what she told him.

“I have lived for 83 years. My mother, Barbara Sierra, lived for 84 years. And my father, Miguel Solórsano, lived for 82 years. One week after the death of Barbara Sierra, my father died of grief at the loss of his lifelong companion.”

Ascención, their only child, was taught the language and the legends of the Westerners by her parents. But with their deaths, the dialogue in the native tongue was relegated forever to the world of the spirits.

She said that the Westerners traced themselves back hundreds of generations to a time when men had descended from the gods and had been placed in Popeloutchom. This was followed by a great flood that caused the ocean waters to rise to the top of the Gabilan Mountains. Following the flood, the founder of the Westerners taught his children how to live on Earth, how to heal illnesses, how to prepare food, build homes and worship the gods. This father and teacher had then departed to the world of the afterlife in the west, beyond the mountains and the sea and the sunset. And there, after death, every Westerner would in his turn be welcomed by the father and teacher. Yet, after death, the Westerners might still visit their children and friends in Popeloutchom in dreams.

Among the Westerners, Ascención said, age was respected and venerated. It was not, as among the white people, considered simply a purgatory prior to death. With age, the Westerners realized, came wisdom and magical powers. Aged women, it was believed, had the power to control the growth of plants.

And death was not something that the Westerners feared. When death came, relatives of the deceased covered themselves with ashes and mourned openly. Some even removed themselves from other members of the tribe for several days and fasted and chanted songs of death.

In Popeloutchom, Ascención said, “nature provided such an abundance of food that the Westerners always had an oversupply of wild fruits, greens and seeds.” Consequently, they did not practice agriculture, nor did they ever cultivate the land. And except for the simple process of gathering food each day, work was completely unknown to the Westerners. They lived like Adam and Eve in Eden. Daily life was organized around leisure and play, and there was neither worry nor care about tomorrow.

The men and boys of the Westerners wore no clothing. And the women wore only a simple brief buckskin skirt. Yet, Ascención asserted, their skin did not burn in the summer sun, nor did they catch colds, even in the most severe winters.

The secret of their health, she believed, was the daily immersion in cold water. Each morning, as soon as they had risen from their sleep, every Westerner walked to the nearest river or stream. Even the tiniest infants were borne along. Then the Westerners jumped into the water and washed themselves. The practice was pursued every day of the year, regardless of the weather. When they left the water the Westerners returned to their dwellings for the morning meal.

The basic food of the Westerners was a gruel consisting of acorn kernels that were crushed and then bleached with water to remove the bitterness, then boiled with meat, fish or greens.

After breakfast each day, the Westerners began their daily activities. The gathering of food and fuel – the most important tasks – were considered an adventure and were carried out in both a communal and a leisurely way.

The men and boys hunted in small groups, leaving the camp each morning and returning late in the afternoon. They roamed the hillsides and the valley floor of Popeloutchom in search of game, especially deer. They were informal during the hunt, always making it more sport than work. When other local bands were sighted, the groups would stop to talk and exchange stories. If game had already been taken, part of it was cooked and eaten by both groups. Athletic competitions – running, wrestling and archery – were also common at these informal encounters.

The Western hunters had learned, through centuries of observation, the habits of their prey, Ascención recalled. They could, therefore, cover themselves with deerskin, walk on all fours like a deer, and approach their prey very closely. A small bird in flight could commonly be hit by most Western archers with a single arrow, so well did they understand the speed and flight patterns of the winged game of Popeloutchom.

In the rivers and streams of Popeloutchom, the men trapped fish in the shallows and then shot them with arrows. Sometimes, when hunting parties traveled as far as the western ocean, they took sea otter, seals and sea lions. And sometimes the hunting parties came upon a small whale that had been trapped in a tidepool or had washed ashore – a magnificent gift from the gods that might feed a single village for weeks.

While the men and boys hunted, the women and girls gathered acorns, roots, nuts, greens, fruits and other foods. In the quest for these, Ascención remembered, they blended conversation, laughter and singing. Like the men, they went out to their decidedly unstrenuous activity in small groups. Collecting firewood meant greater effort and travel, so there was seldom more than a single day’s supply of wood in any village in the valley – even when heavy rain clouds threatened.

The women also provided water for every household in a village. Water was carried from the streams in baskets woven by hand. The baskets were made from the roots of “cut grass,” and when they were filled with water they swelled and did not leak – not one drop, Ascención said.

The Westerners mastered countless crafts and passed the pride of workmanship on to each succeeding generation. The men made beautiful and powerful bows, reinforced with layers of sinew. They were master archers and could string and fire arrows with almost blinding speed. Their arrows, guided in flight by eagle feathers, slipped easily through the body of a deer or a bear.

The women were the weavers of baskets. They sat in a large circle out of doors and constructed baskets while they talked and sang. Each woman’s baskets carried a distinct design that reflected her individual creativity. The patterns were never repeated or copied. And at a woman’s death, her baskets were burned or given away to strangers.

More for sociability than protection, the Westerners lived in small villages. Each home resembled a beehive. They were constructed by driving willow poles into the ground in a circle, bending the tops together and then binding them. Horizontal poles were then laced through the verticals, and deer grass was applied as a cover. A few small holes were left as windows. The door was small and low and faced away from the prevailing winds. The ground served as the floor of the house. Sleeping mats were woven from bullrushes. Robes from deer and bear hides served as blankets.

Fifty years before Ascención was born, the first white men arrived in Popeloutchom, she said. They examined the countryside and named the land San Benito. They then built a mission and named it after a man who paid great deference to the practice of immersion in water – John the Baptist. They called the mission San Juan Bautista; the inhabitants of the 23 villages in the area near the mission were called simply San Juans, referring to their traditional practice of immersion in water. Then they taught the Westerners how to cultivate fields and work and how to pray and how to live. And how to die.

Not long after the first white men had arrived in the region, the gods of the Westerners had demonstrated their grave displeasure with the intruders. The gods, Ascención said, stamped their feet upon the valley floor and caused buildings to fall and great cracks to open in the ground. The white men, of course, were utterly terrified by the quaking of the Earth. They lived outside their homes for several days and nervously questioned the Westerners about the earthquake. But the white men remained. And in the years that followed, again and again the displeased gods of Popeloutchom pounded on the Earth in protest, but in vain. The white people poured in and disregarded the warnings.

John Harrington listened to Ascención’s tales of the Westerners and scribbled down page after page of notes. He was amazed at the comprehensiveness and vividness of her memory.

He was, however, only one of many witnesses to Ascención’s long narrative. Chairs were set up facing the bed in small, even rows, and dozens of local people came daily to sit silently for hours on end and hear this last Westerner sing and chant and whisper the ageless stories of her people one last time.

And as Ascención spoke of a world that was no more and that would never be again, she drew, day after day, untapped reserves of strength. Through October, November and December, she talked and Harrington wrote. Her audiences increased as word of the wise woman’s stories spread. And many of those she had cured traveled great distances to pay their last respects and to hear her last words.

But in January her strength suddenly started to slip away. And as the end neared, she began to hear and see the spirits of the Westerners in the room and outside the house, reminding her of stories she had not yet told and beckoning her to finish her work. As she spoke, more slowly now and almost in a whisper, she would suddenly point to someone sitting at her bedside and say, “The spirit of my father, Miguel, is sitting beside you!” Then she would speak to Miguel in a language no one in the room had ever heard before and would never hear again.

Finally, she heard the spirits of her race tapping at the door, summoning her. She had told John Harrington all she remembered of Paradise, a place once called “Popeloutchom.” Now she gazed at Harrington once more in silence for a long time. It was a sad, piteous look. But the sadness and the pity were not for herself, but for Harrington and for those of us who would read what she had whispered and he had written, and who would never ever look upon a place in this world as beautiful as her Eden, her Popeloutchom.

She closed her eyes and began very gently picking imaginary flowers from the blanket. Then, peacefully and without any struggle, she stopped breathing.

It was January 1930 when the last Westerner left Popeloutchom. The next morning some of the baskets she had woven were burned, and the others were given away to strangers.