By Ben Barker / Deep Green Resistance Wisconsin

There’s no such thing as a functioning group of human beings existing without leadership or structure. That sentiment, while exalted by many on the radical Left, is a fallacy. Whether or not we want it to be true, human beings are by nature social creatures and we learn by the example of others, which is to say we learn from those we look up to and from the customs of the culture we live in. Leadership and structure are inevitable. The only questions are by who? and how?

Sure, radicals can reject this notion and operate as if it didn’t exist—it’s what many are already doing. But, all the while, our groups still move in particular directions, and it’s the members that take them there. Those who wish to prohibit leadership and formal structure are really just spawning informal versions of both, with themselves at the helm of control.

There’s a long history of this. From the anti-war movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s to the anarchists and Occupy movement of today, “leaderlessness” is almost taken as a given; it’s praised as an obvious first step in challenging power inside and out. Again and again, however, we see this paradox’s predictable outcome: when structure is not explicit, it takes its own form—one usually shaped by those most willing to dominate the group.

This was the lesson of the classic Leftist essay, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” in which author Jo Freeman argues that, as movements “move from criticizing society to changing society,” they need to honestly and openly address how they will organize themselves. “[T]he idea of ‘structurelessness,’” she writes, “does not prevent the formation of informal structures, but only formal ones.” So in all the backlash against formality, activists are only serving to undermine their own supposed ethics by contributing to unspoken rules and hierarchy.

Intentional organization may or may not lead to the egalitarian, functioning movements we desire—there are clear cases of both the success and failure of formally structured groups. Done well, however, structure can provide a means of accountability between members that their structureless counterparts inherently lack. In the best case scenario, the group’s expectations and rules (I hear the shrieking of purists already) are explicit and accessible to everyone, allowing leaders and followers alike to keep each other in check.

“A ‘laissez-faire’ group is about as realistic as a ‘laissez-faire’ society,” Freeman writes. “The idea becomes a smokescreen for the strong or lucky to establish unquestioned hegemony over others.” Too frequently the backlash against group structure is a deliberate attempt on the part of a few to maintain invisible and unquestioned authority over a group’s ideas and direction. So begins elitism.

Jo Freeman claims that elitism was possibly the most “abused word” in the movements of her time and I’d say the same is true today. The term is too often thrown out thoughtlessly and on any occasion of mere disagreement. It becomes a tool for those who want to destroy potential for leadership; public attention of any kind is in this case conflated with power-grabbing and exclusivity, with elitism.

Still, elitism is very real and has very real consequences. Freeman writes, “Correctly, an elite refers to a small group of people who have power over a larger group of which they are part, usually without the direct responsibility to that larger group, and often without their knowledge or consent.”

There are numerous myths about what constitutes elitism: public notoriety, social popularity, the inclination to lead. But none of these are sufficient descriptors of the phenomenon. More than anything, accusing one of being an elite based on such qualities speaks to the paranoid and destructive tendencies of the accuser. As Freeman writes, “Elites are not conspiracies. Seldom does a small group of people get together and try to take over a larger group for its own ends.” She continues, “Elites are nothing more and nothing less than a group of friends who also happen to participate in the same political activities.”

Not surprisingly, these friends will—sometimes unthinkingly, sometimes intentionally—maintain a hegemony within the group they are part of by agreeing with and defending each other’s ideas almost automatically. Those on the outside of the elite group are simply ignored if unable to be persuaded. Their approval, says Freeman, “is not necessary for making a decision; however it is necessary for the ‘outs’ to stay on good terms with thin ‘ins’.” She continues, “Of course the lines are not as sharp . . . . But they are discernible, and they do have their effect. Once one knows with whom it is important to check before a decision is made, and whose approval is the stamp of acceptance, one knows who is running things.”

Unspoken standards define who is or is not entitled to elite status. And they have changed only slightly since Jo Freeman brought activist elitism under the spotlight; most have endured the test of time, destroying our movements and inflicting pain on many genuine individuals. Such standards include: middle-to-upper-class background, being Queer, being straight, being college-educated, being “hip”, not being too “hip”, being nice, not being too nice, holding a certain political line, dressing traditionally, dressing anti-traditionally, not being too young, not being too old and of course, being a heterosexual white male. As Freeman notes, these standards have nothing to do with one’s “competence, dedication . . . . talents or potential contribution to the movement.” They are all about selecting friends and contribute little to building functioning community.

Of course friendships are crucial to resistance; they represent trust and perseverance between freedom fighters, an absolutely necessary quality for the high-pressure nature of taking on systems of power. But basing our activist relationships on who we pick as friends—those who pass the test of those arbitrary standards—creates circumstances ripe for nasty division and social competition. And, writes Jo Freeman, “[O]nly unstructured groups are totally governed by them. When informal elites are combined with a myth of ‘structurelessness,’ there can be no attempt to put limits on the use of power.” Friend groups must confront this potential disaster by being honest and upfront about their relationship to one another. Further, they should advocate for transparency and processes of accountability. It is up to such friend groups to ensure that they do not succumb to elitism.

The same transparency and accountability must apply to leaders and spokespeople. It is not entirely the fault of those who fill those roles when they are viewed as insular gate-keepers of the movement. Without a forthright decision-making process, there’s no way for other members to formally ask to take the lead on a project or to publicly represent the group at any given time. Yet, some are naturally inclined to take initiative, and because they are not explicitly selected by their comrades to do so, they become resented and, too often, ousted.

And what does this accomplish? The group is left without energy to move it forward and the activists kicked out are now even less accountable to the movement of which they were once part. This purging has no future. Instead, our movements should be open and honest about what we want to convey to the public, who will say it, and when. If anyone is to be ejected, it should be because they consciously betrayed the trust of their comrades, not because they took initiative.

Unstructured groups may prove very effective in encouraging people to talk about their lives; not so much for getting things done. This is true from the micro to the macro; whether we’re talking about facilitating meetings, getting food to frontline warriors, or planning a revolution. Says Freeman, “Unless their mode of operation changes, groups flounder at the point where people tire of ‘just talking’ and want to do something more . . . . The informal structure is rarely together enough or in touch enough with the people to be able to operate effectively. So the movement generates much emotion and few results.”

Much emotion and few results. This is the standard mode of radical subcultures.

Structurelessness may be a romantic idea, but it does not work. The floors still need sweeping, the food still needs cooking, and if tasks aren’t explicitly assigned, they will, without fail, implicitly fall on the shoulders of a couple tired leaders. Frontline combatants cannot afford that sort of confusion; they need a detailed plan of action. Going with the flow might work fine for a potluck, but in a serious movement the flow will only lead activists into dangerous situations, wasted time, and compromised actions.

Jo Freeman continues: “When a group has no specific task . . . . the people in it turn their energies to controlling others in the group.” She goes on, “Able people with time on their hands and a need to justify their coming together put their efforts into personal control, and spend their time criticising the personalities of other members in the group. Infighting and personal power games rule the day.” The forecast was dead-on.

What can we do to save our communities and movements (or even build them in the first place)? The answer seems crazy, but really it’s simple: work together. In this age of immense individualism and pettiness, it may sound impossible, but I truly believe that, despite a few (often insignificant) differences, activists really can find common ground and tolerate one another long enough to make some tangible political gains. Sometimes, all it takes is having something to do. As Freeman notes, “When a group is involved in a task, people learn to get along with others as they are and to subsume dislikes for the sake of the larger goals. There are limits placed on the compulsion to remould every person into our image of what they should be.”

By adhering to an ethic (or is it non-ethic?) of leaderlessness and structurelessness, we set our movements up for failure. The longer groups continue on such a basis (or is it non-basis?), the less likely the pieces will be able to be picked up after the project inevitably collapses. And, as Freeman points out, “It is those groups which are in greatest need of structure that are often least capable of creating it.” Tedious and unglamorous as the work may be, we desperately need to learn to develop structure from the beginning, rather than hoping and praying it will come together organically. The fact is it almost never does and the result is a take-over by elitists who only run movements into the ground.

Structuring groups is hard work. Without structure, our energy is diffuse and largely ineffective. But bad structure almost always leads to crisis and, like a building that grows and grows until it all comes crumbling down, it often does more damage to those involved than it would have had there been no structure from the outset. And yet, the resistance movements this world needs require a means to stay organized and effective.

Here’s a story from just this week: “[Britain’s] largest revolutionary organization has been shaken by the most severe crisis in its history, stemming from the failure of its leadership to properly respond to rape and sexual harassment allegations made against a leading member, and, in turn, from attempts to stifle discussion of this failure and its consequences.” One leading member noted that “the party’s internal structures don’t have the capacity to judge cases of rape.” Need I say that radical groups desperately need this capacity? If we don’t know how to handle sexual assault—or any sexism, for that matter—when it arises, if we don’t know how to kick out rapists from our groups, how are we supposed to have the capacity to work together in dismantling vast systems of power?

What’s the alternative? In “The Tyranny of Structurelessness,” Jo Freeman offers seven “principles of democratic structuring as solutions that are just as applicable now was they were then. The first is delegation: it should be explicit who is responsible for what and how and when they will do the task. Further, such delegates must remain responsible to the larger group. Accountability ensures that the group’s will is being carried out by individual members.

Next is the distribution of decision-making power among as many members as is reasonably possible. Following that, rotating the tasks prevents certain responsibilities from being solely in the domain of an individual or small group who may come to see it as their “property.” Allocation of these tasks should be based on logical and fair criteria; not because someone is or is not liked, but because they display the ability, interest, and responsibility necessary to do the job well. Next, information should be diffused and accessible to everyone as frequently as possible. And lastly, everyone should have equal access to group resources, and individuals should be willing and ready to share their skills with one another.

Such principles are easy to write or speak about, but much harder to put into practice. People without much power over this society are prone to grasp for it when they get a taste, but too often they are just stealing from yet another powerless person. Writes Florynce Kennedy: “They know best two positions. Somebody’s foot on their neck or their foot on somebody’s neck.” So, it is imperative that we safeguard against the pitfalls of horizontal hostility, especially as we work to create fair and effective structure. Leaders must be held accountable for the power they have. At the same token, we can no longer allow leadership to be systematically stomped out. We can no longer allow the tyranny of structurelessness.

Beautiful Justice is a monthly column by Ben Barker, a writer and community organizer from West Bend, Wisconsin. Ben is a member of Deep Green Resistance and is currently writing a book about toxic qualities of radical subcultures and the need to build a vibrant culture of resistance.

Were you here for the Vietnam war? Ben. Did you see the atrocities of a well-led US war machine halted by a leaderless movement of people bound by the draft? It was the first time in history that a conquering hierarchy of idiotic generals and political leaders was stopped by the people ordered to destroy another country. The threat of leaderless democracy during the Vietnam war so frightened corporatists that they immediately quit using the democratic draft and began undermining the security of their own population so it could not happen again. It is no mistake of chance that my minimum wage at the age of fourteen was sufficient to buy 11 candy bars plus 11 sodas per hour. Leaderless non hierarchy is the opposite direction of what we have, it is the way to bring forward the consciousness of nine billion people living in the huge metro regions of modern civilization. You may author long statements to deny modern information-age concepts of civilization as a living being and you will then wonder what you are seeing unfold, a human meadow flowering with now more leadership then a meadow in a mountain valley during spring.

Great article Ben, thank you! I have posted an abridged version on a page used for internal discussion in a large permaculture organisation I am part of:

http://www.facebook.com/notes/at-the-farm-nscf/tyranny-of-structurelessness/303225816446753

Murray: Thank you!

Garrett: From what I understood of what you said, we have differing opinions about leadership. I understand that movements have strategically not publicly named their leaders, and this is fine and great when it works, but that doesn’t mean no one is pushing the efforts forward from the inside.

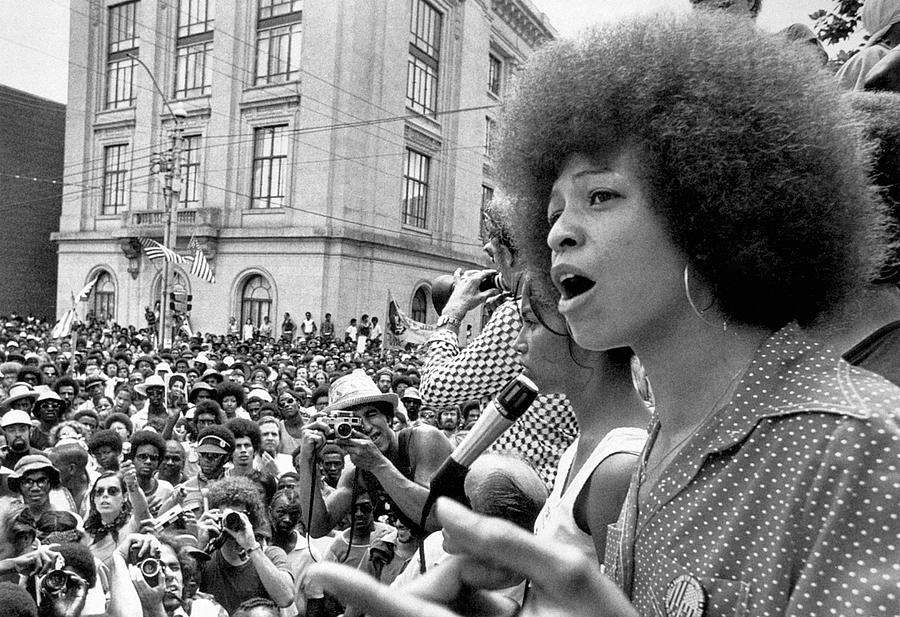

Ben, I am thinking more of a future information-age government that grows parallel to the existing representative democracy, a participatory democracy where voting is around ideas and proposed actions. Leaders end up being like Obama, Clinton, Bush or Holder etc, anti-life propagandists who obscure the human spirit for personal power. It is the people at large who are the vessel of civilization and hold a vision broad enough to include respect for the planet. Though there will always be wonderful people like Dr. Cornell West, Martin Luther King and Angela Davis, great teachers who prod us to be better, humanity as a specie is too easily lulled into thinking authors, movie stars and great orators with high energy have the answer. When the people are talked at they go home and let the famous leaders handle the job. And when those leaders become corrupted by power the people become cynical and withdraw further. Leaders have been attempting to take over since civilization began, the modern world needs a new story, one that sees average humans as cosmic powered beings surfing Big Bang at life speed, far faster than light. Human beings are powerful enough to be humble and live in peace with Mother earth yet are easily confused and distracted by leaders that perhaps see a tiny bit more on their best days. When all humans are leaders then the power hungry cannot succeed.

Garrett: I fully agree that we need need leader-ful movements; one where everyone is encouraged to take initiative.

Great thoughts here, Ben!

I wonder to what extent the structure of groups is a microcosm of the structure of society in general, and how looking at societal structures might inform this inquiry into group structure. There seems (some have said) to be a part of society that is concerned with the ways in which all parts of the whole are equal, with the common good, and with the responsibilities that each part has to the whole (you might call this the “We” part). There also seems to be a separate part of society that is concerned with the parts themselves, with the rights of each individual (the “I” part). These two parts interact in a third and separate part, the realm of the economy.

Such an understanding of societal organization (if taken to be valid) might be helpful to group organization. For one can hopefully begin to see the necessity of balance: The group, or “We,” is out of line when it asks the individual “I” to sacrifice its interests to the totality. “We” exists FOR individuals, for “Is” — groups are meant to support individual development. But, on the other side of the equation, “Is” are out of line when they safeguard only their own interests or rights, “Is” exist FOR, are responsible to, the whole group, to “We.” Hence, (and this is not my quote): “The healthy social life is found when in the mirror of each human being the whole community finds its reflection, and when in the community the virtue of each one is living.”

Take these ideas further and you can begin to tease out living structures or guidance for groups along the lines of Jo Freeman’s. For instance, the group should create structures or arrangements that do not permit individuals to claim the fruits of their own work for personal use. The individual needs of individuals should be met by others in the group. Individual motivation to work will decrease the less one consciously experiences the reality of the common task of the group, and the less the individual is active in the formation of concrete common goals. Individuals must be free to apply their unique capabilities, and equality is the fundamental impulse in the realm of the “We” (also called the “government”). Etc.

Thank you, Ben. I have been reading “Changing Venezuela by Taking Power.” Interesting points here are the writing of a new constitution that becomes a goal for society, an interesting method of leadership, and establishing five branches of government by adding the people’s branch to ensure laws are forged in the heart of justice, and the information-age branch the battles the drift to secrecy and misinformation in the media and education system.

Write on, Jeff. You are looking at the group, nation and specie as a living being dependent upon the health of each individual?

Just a quick response to Garrett’s initial comment:

“Were you here for the Vietnam war? Ben. Did you see the atrocities of a well-led US war machine halted by a leaderless movement of people bound by the draft?” —

The US war machine was actually stopped because it was militarily defeated by the National Liberation Front — very highly organized (by communists btw), and in general the Vietnamese people. The protests and various forms of resistance in the US were positive but supplementary.

Stephenie, you weren’t born yet either?

One reason as to why so many groups have this huge problem with leadership is because of the dominant cultures take on authority. Its pretty nailed into us all that leadership is the same as being an authority and authority is, at least to me, something I don’t look upon with happy eyes its someone that tells you what kind of moral is right and wrong and what you can’t and cannot do without having to listen to anything you have to say. To work under the notion of “the ways things are”.

But reality is of course that being a leader does not mean you have to be an authority at all. A good leader acts on the behalf of the group and has a healthy non-hierchical relation to individuals in the group.

Thank you, Sundazed. Each person is a leader at one time or another. Now we evolve to a democratic civilization that focuses the wisdom of seven billion and enrolls them in medicare, at the same time, everywhere on Earth. A good leader hears the ring of truth and works to help the good in humanity blossom. We know we are children of the cosmos and mother Earth. Humanity is a river of knowledge, consciousness manifest in a vibration of sub atomic waves stretching back to the first moment surfing Big Bang, and adding to each individual and civilization now. Another world is possible, it will occur when a new story we all like is accepted by most of us as reality. Leaders tell stories and hope a good one catches on.

The 60s failed to fundamentally redefine the political authorities of government. We left it to the political parties. We disenfranchised and marginalized the very 99% Occupy claims to speak for today. It was NOT leaderless. But it also faced repression. It is time to debate Federalism and the authority of the Federal government, particularly, but not exclusively, the Executive Branch. I recommend a bioregional model. see http://www.newclearvision.com/2011/03/07/water-as-a-human-right/#more-335 As things stand today, political elites game and script discourse and define “change” as it suits their interests. Advocacy groups have a vested interest, as potential contractors, to maintain the status quo. Policy debates are kabuki theatre. There have been no movements because there is no fundamental proposal to restructure government. We continue to make the proposition that a new face means a new start, when it simply means “business as usual”.

“Those who wish to prohibit leadership and formal structure are really just spawning informal versions of both, with themselves at the helm of control.”

Perfectly said: most people I knew who greatly criticised leadership and formal structure and any form of domination, had themselves the most dominating of personalities really. When I told them they had leadership qualities, they would staunchly deny it and wind up being overly controlling sub-consciously. It is as though by resisting their own natural selves, to lead, by denying it in others, they are projecting on others their discontent with themselves, and wind up doing exactly what they dislike in others. Rather like a psychological repression of the self.