This excerpt is from Derrick Jensen’s unpublished book “The Politics of Violation.” It has been edited slightly for publication here. The book is in need of a publisher. Please contact us if you wish to speak with Derrick about this.

For more than two thousand years, a war has been waged over the soul and direction of anarchism.

On one hand, there are those who understand the straightforward and obvious premises that at least to me form the foundation of anarchism: that governments exist in great measure to serve the interests of the governors and others of their class; and that we in our communities are capable of governing ourselves.

And on the other hand, there are those who argue that all constraints on their own behavior are oppressive, and so for whom the point of anarchism is to remove all of these constraints.

I researched and wrote this book in an attempt to understand this war, in the hope that understanding this war can help us understand how and why anarchism has become a haven for so much behavior that is community- and movement-destroying; how and why a movement claiming to show that humans are capable of self-governance so often seems to do everything it can to show the opposite; how and why a movement that claims to be about ending all forms of oppression can be so full of bullying, abuse, and misogyny.

If we all understand this, might we as a society move both anarchism and the larger culture away from these behaviors and toward more sane and sustainable communities?

It became clear to me, however, that the book is about more than anarchism. In part it’s about differences between understanding and learning from a political philosophy—any political philosophy—and turning that philosophy into an identity; what happens when the former ossifies into the latter. This is a problem not just in anarchism but in more or less all philosophies.

When Harm is Left Unchecked

A strength of anarchism is that many anarchists are willing to struggle for their beliefs, and to fight power head on. A weakness is that too many anarchists are too often not strategic, tactical, or moral in choosing their fights, including how they will fight, and in choosing the targets of their attacks.

Severino di Giovanni provides a great example from the 1930s. He was an anarchist in Argentina who started a bombing campaign targeting fascists and also, because of the killings of Sacco and Vanzetti, bombing targets associated with the United States. We can argue over whether his actions were appropriate. And the anarchists in Argentina certainly did argue over it, which leads to why I bring him up: one of the anarchists who spoke against his bombing campaign (saying it would lead to a right wing coup, which in fact happened soon after) was murdered.

Guess who was the prime suspect in his murder?

…

I could provide hundreds of examples of atrocious behavior that have become normalized among too many anarchists. For that matter I could provide hundreds of examples that have happened to me, from threats of death and other physical violence to the posting to the internet of pictures of me Photoshopped to simulate bestiality. Probably the most telling action has been that anarchists arranged for my elderly, disabled, functionally-blind mother to receive harassing phone calls every fifteen minutes from 6:30 a.m. to 10:30 p.m. for weeks on end.

The point isn’t that they did this to me (and my mother): I’ve known too many people who’ve received their own version of this treatment.

Part of the point is that some people are terrible human beings. Change a few details, and anyone could tell similar stories from most other movements or organizations. And so this book becomes a case study of some of the harm terrible human beings can, if left unchecked, do to movements.

So, generically: What sorts of terrible people does your movement/organization support? And what harms do these people cause? Ecofeminist Charlene Spretnak has written extensively on social change movements, and has talked about how abusive behavior drives away people, especially women, in “huge numbers. That’s a brain- and talent-drain these movements cannot afford.”

What can we do about that?

An Insult to One is Injury To All

Here’s another example of the sort of community-destroying behavior that has come to characterize too much anarchism. A few years ago, I was discovered by the Glenn Beck arm of the right wing. Within two weeks I’d received literally hundreds of death threats from them, many of which were highly detailed in what was to be done to me (e.g., photos of castration) and in information about where I live, my schedule, and so on. In response to these threats I bought a gun and installed bars over my doors and windows. I also called the police and the FBI. I didn’t believe the police and FBI would be particularly helpful (they weren’t), but I wanted for there to be an official record of the threats for two reasons. The first is that on the remote chance someone did kill or injure me, people would at least have an idea where to start looking for the perpetrators. The second is that if someone attempted to harm me and I had to use lethal force to protect myself, it would already be a matter of public record that I had reason to fear for my life. I could imagine a court scene playing out after I was charged with murder for killing someone who had attempted to kill me.[1]

The prosecuting attorney asks, “Were you afraid for your life?”

“Yes.”

“Did you call the police?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

A long silence while I consider that it wouldn’t be particularly useful to say I didn’t call the police because to do so is evidently against anarchist ideology.

The prosecuting attorney continues, “Then I guess you weren’t very afraid, were you?”

Trial over. I lose.

The point is that when I told my neighbors I’d received death threats, they responded as you’d expect decent human beings to respond—with sympathy and expressions of concern for my safety. Some took tangible steps to help guarantee this safety. For crying out loud, a member of the local Tea Party helped me install the bars. This is what members of a community do. An insult to one is an injury to all, remember?

On the other hand, with few exceptions I received little positive support from anarchists, who instead accused me of making up the threats, called me a coward for paying attention to them (many of these particular comments were, ironically enough, anonymous), threatened to kill me themselves, or excoriated me for calling the police.[2] Anarchists quickly labeled me a “cop lover,” then “pig fucker,” then “snitch,” then “someone who rats out comrades.” Soon, anarchists were accusing me of “regularly working with the FBI and the police,” and of being a “paid police informer.” It wasn’t long before some were saying, “Word on the street is that he’s been a fed from the beginning. They wrote all his books.”

To Distort is To Control

How does a political philosophy that leads people to act as did those young men I described who became bodyguards for the victim of a sexual assault lead others to act so despicably? How can anarchism be so easily and forcefully used, as it has been, as an excuse for men to sexually or otherwise physically assault women? How can anarchism be so easily and forcefully used to support, as we’ll see, the sexual abuse of children? And how can we prevent all of this from happening in the future?

Can anarchism be fixed?

We should ask these questions of every social movement. This questioning is especially important for those who are inside these movements.

Change a few words, and this book could have been written about almost any social movement or group. I know female Christians (now former Christians) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male Christians, and then pressured by the Christian community not to go to the police because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

I know female soldiers (now ex-military) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male soldiers, and then pressured by the military community not to go to the police because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

I know female athletes (now former athletes) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male athletes, and then pressured by the local athletic community not to go to the police because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

I know female police officers (now former ones) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male police officers, and then pressured by the local police community not to go to the police (!!) because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

Substitute the words musicians, teachers, loggers, environmental activists, actors, writers, and the story is the same.

So this book provides an exploration of what rape culture does to movements, and how movements are deformed or destroyed by the imperative to violate that is central to patriarchy, central to the dominant culture.

I’ve long been a critic of Christianity, but I can’t tell you how many times, especially when I used to drive beaters (I bought four cars in a row for one dollar each, and considered these good deals since the cars must have been worth at least twice that much), that I’ve been stuck by a road, and the person who stops to help fix my car has been a Christian stranger, motivated by a calling to do good in the name of their belief system. Yet, Christianity has been and still is used to justify—and leads to—atrocious behavior such as gynocide, genocide, ecocide. When I think of Christians, I think of a wonderfully kind man and woman who invited me into their home when I was living in my truck in my twenties. And when I think of Christians I think of misogynistic, racist, pro-imperialist buffoons. I think of Christians rationalizing slavery, rationalizing capitalism. I think of Christians burning women they considered witches, burning Native Americans, burning the world. I think of Christians burning other Christians. How does a religion that leads to wonderful people like the couple who gave me a place to stay also lead to such routinely atrocious behavior?

Likewise, when I think of the American Indian Movement, I think of brave women and men standing up to the United States government and to corrupt tribal governments. And I think of misogynist murdering assholes raping and killing Anna Mae Aquash, among others.

When I think of the Black Panthers I think of free breakfast programs for children and black pride and protecting neighborhoods from police violence. And I think of systematic programs of rape by male Panthers against women both black and white.

I’m sure you can find your own examples.

What is wrong with these movements?

Justifying Oppression

Obviously, anarchism is not the only philosophy that has been used to rationalize or facilitate the sexual exploitation of women. We’d be hard-pressed to find philosophies within patriarchy that haven’t. And certainly, groups other than anarchists have facilitated this exploitation. Organizations from the police to the courts to the military to churches to universities to professional sports organizations to the NCAA to the music industry to the Boy Scouts to pretty much you-name-it have facilitated or covered up sexual assaults by men on women or children.

Those of us who care about stopping atrocities need to ask: How does any particular philosophy justify or otherwise facilitate atrocious behavior? And what are we going to do to stop these atrocities?

Panem et Circenses

I became interested in anarchism when I first became politicized—that is, when I began to understand that, as economists are so fond of saying and even more fond of then ignoring, there is no free lunch. In other words, all rhetoric and rationalization aside, the wealth of some comes at the expense of others.

In other words, empires require colonies.

It immediately became clear to me that while much of how a state disperses resources (e.g., time and money) could be perceived as citizen maintenance,[3]—or, with thanks to Juvenal, providing enough “bread and circuses” to keep the exploited from tearing out the throats of the rich—the state’s most important function by far, and the primary reason for its existence, is to take care of business; that is, to take care of the interests of those in power.

Burden of Proof

So there’s a sense in which the bad behavior of too many anarchists is not only appalling but tragic, Bad behavior among anarchists represents thousands of years of lost opportunity for meaningful social change, because while some anarchist analysis makes sense, the behavior of too many of those who call themselves anarchists can get in the way of people wanting to share a movement with them.

The sensible analysis begins with this: The state isn’t necessary for human survival, and in fact the state primarily serves the interests of the governors and others of their class.

If you don’t believe governments primarily serve the interests of the governing class, ask yourself if you believe governments take better care of human beings, or of corporations. If governments had as their primary function the protection of human and nonhuman communities, would they devise a tool—the corporation—that exists explicitly to privatize profits and externalize costs, that is, to funnel wealth to the already wealthy at the expense of others? I’ve asked tens of thousands of people all over the United States and Canada if they believe governments better serve humans or corporations, and no one ever says humans.

Let’s throw in a couple more common-sense comments about anarchism. The first is by the American linguist, philosopher, scientist and activist Noam Chomsky (who, by the way, is also hated by many of the anarchists on the wrong side of the war for the soul of anarchism, who call him “a pussy” and “the old turd”): “That is what I have always understood to be the essence of anarchism: the conviction that the burden of proof has to be placed on authority, and that it should be dismantled if that burden cannot be met. Sometimes the burden can be met. If I’m taking a walk with my grandchildren and they dart out into a busy street, I will use not only authority but also physical coercion to stop them. The act should be challenged, but I think it can readily meet the challenge. And there are other cases; life is a complex affair, we understand very little about humans and society, and grand pronouncements are generally more a source of harm than of benefit. But the perspective is a valid one, I think, and can lead us quite a long way.”[4]

Makes sense, right?

Now let’s throw in another, by Edward Abbey: “Anarchism is not a romantic fable but the hardheaded realization, based on five thousand years of experience, that we cannot entrust the management of our lives to kings, priests, politicians, generals, and county commissioners.”[5]

This all seems pretty obvious, and leads to the question, why aren’t more people anarchists?

[1] And most of us have read accounts of this sort of thing, for example, so many of the women in prison for killing their abusive husbands. In the town where I live a woman is right now being charged with murder for shooting her husband in front of witnesses who all swear that he routinely beat her, that this night he was punching and kicking her, and just before she shot him he yanked her by her hair out of a car as she was attempting to escape. Even the dead man’s mother is begging prosecutors to drop the charges.

[2] This whole question of never speaking to the police cuts to the heart of one of the problems with too much anarchism. Just as with any rigidified ideology, the ideology itself comes to supplant circumstance and common sense. For example, when attorneys advise you never to talk to the police, they mean when you’re under suspicion, not under every circumstance. If anarchists saw Ted Bundy knock out a woman, load her into his car, then drive off, they wouldn’t call the cops? What are they going to do, hop on their bikes and pedal after him?

[3] Such as providing water and waste disposal for the people. But the fact is agriculture and industry account for more than 90 percent of human water usage and 97 percent of waste production. Governments “take care of” big business under the guise of “citizen maintenance.”

[4] Doyle, Kevin, “Noam Chomsky on Anarchism, Marxism, and Hope for the Future,” Red and Black Review, 1995, http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/rbr/noamrbr2.html – Site visited 6/20/2016.

[5] Abbey, Edward, A Voice Crying in the Wilderness, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1990.

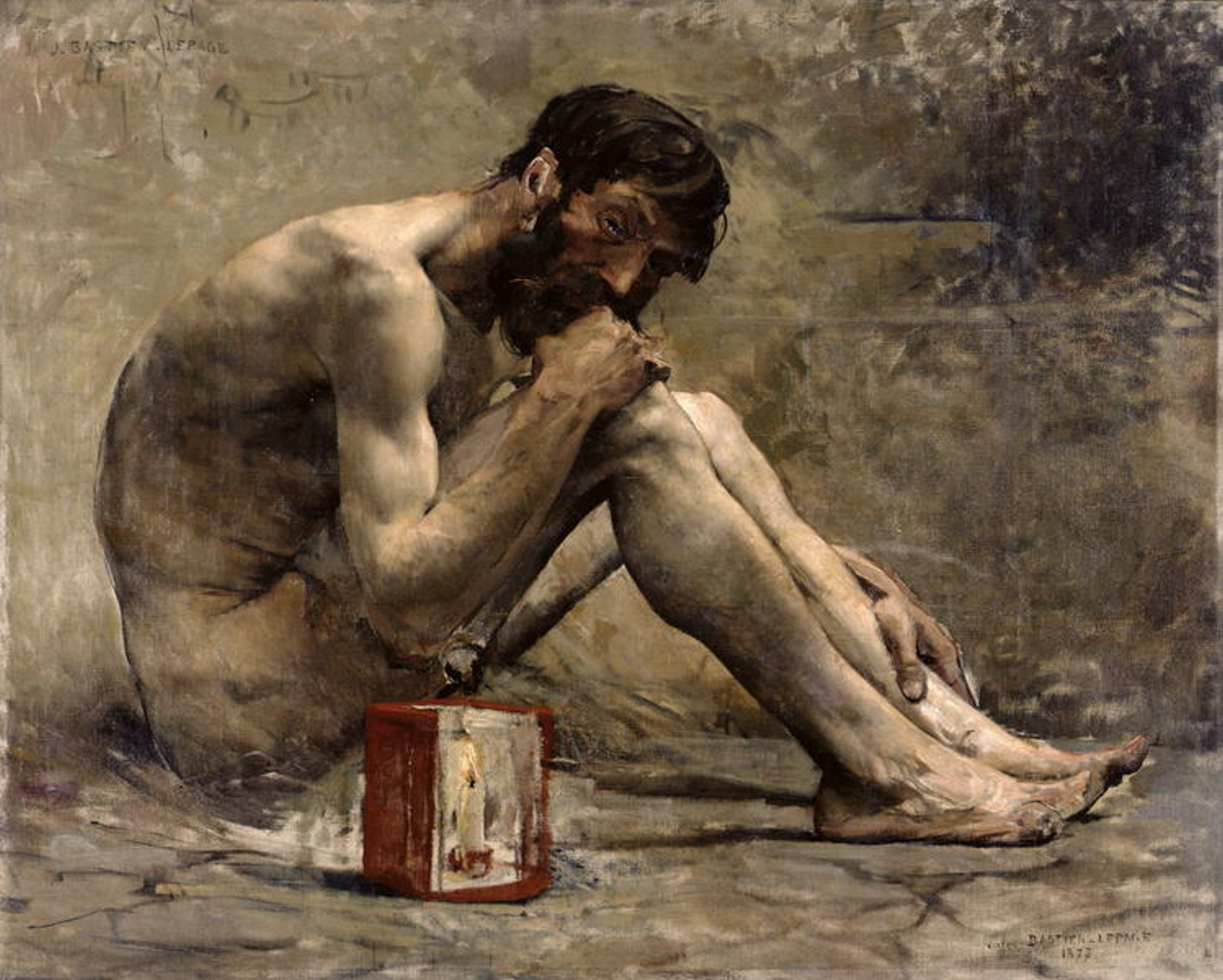

Featured image: 1873 painting of Diogenes, an ancient Greek Cynic and prominent figure in proto-anarchism. By Jules Bastien-Lepage.

About the Author

Derrick Jensen is a co-author of Deep Green Resistance, and the author of Endgame, The Culture of Make Believe, A Language Older than Words, and many other books. He was named one of Utne Reader’s “50 Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World” and won the Eric Hoffer Award in 2008. He has written for Orion, Audubon, and The Sun Magazine, among many others.

Derek,

Thank you for this needed, very coherent, treatise.

There are legitimate reasons to be skeptical of Chomsky as he defended US military presence in Rojava to “protect the Kurds” or something. (Source: https://theintercept.com/2018/09/26/trump-united-nations-noam-chomsky/)

I’m not defending abusive anarchists – I despise them as much as you guys do – but this shouldn’t become a reason to defend Chomsky either. Like Bernie Sanders, he’s an empire propagandist posing as a leftist.

The problem with anarchism is the problem with all “isms,” which is the problem with humans: We all have beliefs, and we all believe something different. Most of us live within some sort of social organization or community, which we support enthusiastically until we discover that others within that group disagree with us. In other words, we’re antisocial socialists.

That’s why I’ve never quite identified as an anarchist. Almost all anarchists believe something that I don’t believe. Most of us, I suspect, could come up with a simple program for solving the world’s problems. And most of those solutions would boil down to, “Do things my way and we’ll all be okay.” Except that my way isn’t your way. The joke Jews tell on themselves is pretty close to a universal truth: In any group of three Jews, you’ll get at least four different opinions. We all disagree. And given enough discussion, we’ll disagree with ourselves, too.

Indigenous communities overcome this only by being too busy surviving to philosophize, and by not having a written language. So long as no one can write, disagreements die pretty quickly. And so long as your social organization doesn’t far exceed 200 people, most people can go along with the basic rules of survival. And to prevent disagreements even at that level, someone comes up with a few myths or superstitions, declares them to be handed down from a higher power, and the group adheres to them out of fear of karma, divine retribution, or the Great Spirit.

The Great Spirit myth, hoeever, works pretty well — not because it’s true, per se, but because it’s based on natural law. Nature sometimes appears to be and IS brutal (predation is murder, no matter how you rationalize it; and volcanic eruptions can be genocidal, whether there’s a god in the mountain or not). But it has allowed life to continue for a billion years or so, which beats the hell out of any other ism’s record.

As for calling the police, I’ve only done it once, which was to report that a drunken neighbor had threatened to shoot me if I complained about his drunken screaming anymore. I told them I didn’t know if he had a gun, but that I do, and would use it if he came to my door again, based on his previous threat. And the one time a neighbor called the police on me, they came out and listened to his complaint, and then arrested him on an outstanding warrant.

We all want a police force as long as it’s on our side. But when we advocate destroying civilization, that’s rarely going to be the case.

The right generally wants as little government as possible, because they like to believe they can take care of themselves. Unfortunately, that often means taking more than their share –whether it’s in the form of fencing land, or running a global extraction corporation.

The left tends to like more government, because leftists tend to be victims of power grabs by the right. Leftists also tend to live in cities — not because cities are inherently good, but because exceeding the village limit of 200 or so increasingly creates needs that can’t be met without government.

As for Chomsky, he is widely acknowledged to be one of the great minds of our time. And as a product of civilization, he is also a part of it, and a frequent target of both its supporters and its detractors. He preferred Roosevelt to Nixon, for instance, despite the military draft, the Manhattan Project, and the incarceration of every Japanese American on the West Coast — all of which were war crimes. And he made that decision not because Roosevelt was a war criminal, but because Roosevelt was a war criminal with more integrity and generally better intentions than Nixon.

Similarly, we’re all hypocrites here, too. We’re using the highest products of technology (computers, the Internet, and electricity produced by raping the Earth, for instance) to make various arguments against civilization and all its products.

Such is the nature of humanity. Our brains are too big for our institutions. Or, as my mother used to complain of me, “You think too much.”

(Note to anyone else out there who has or aspires to have unpublished books: A first-time novelist was interviewed on NPR’s “Fresh Air” awhile back. After more than 100 rejection slips, she decided to self-publish online. She spent $2700 for someone to do the layout and promotions for her, and was told that online books generally sell for around $10 — or $3, if you’ve never published before. Desperate for readers, she priced hers at $1, and sold 130,000 copies in three months. After that, mainstream publishers were soliciting her for work.)

@Mark Behrend: a fine account of why I’m not quite an anarchist either. I can’t envision a practical means for large numbers of humans to govern ourselves individually. Anarchist writings I’ve glanced over seem vague on the details that matter.

“The right generally wants as little government as possible…” only insofar as governments who would regulate their profitmaking. They love big, state militaries and paramilitary, unaccountable police forces to protect their interests. And they love big governments creating bailout funds when capitalism undergoes its frequent crises, as now.

It’s always difficult to be reminded that even those who are presumably putting up a fight against empire are not morally superior to and are even more despicable than the psychopaths who are destroying our environment. It leaves the average person in a state of despair as to whom s/he can trust to follow since nobody can face the juggernaut of industrial civilization alone.

Deep Green Resistance is not immune to the kind of misogyny and silence for the sake of the community that has been described here. I believe there are a few people who know why I am no longer a member of the organization even though I have pretty much kept the story to myself.

I walked away partly out of (misplaced) shame and partly to protect “the cause”. I will never know why everyone else who was present sat on their hands and looked at the ground rather than standing up with me and for the ideals expressed by the organization.

I do know that any organization will have a hidden hierarchy and unspoken set of rules. I suspect that many people are unaware of how well their behavior matches that which they claim to be fighting. I believe that much of the time people are not “bad” but the organization will always be the overlord even if it is disguised and/or denied. I also know that in any hierarchy someone has to be at the bottom of the heap. Acknowledging the realities that are a part of any group would go a long way towards alleviating the functional hypocrisy that “…drives away people, especially women …..”.

“Anarchy” is a utopian ideal, not a practical form of governance with anywhere near this number of people on the planet (another of the countless reasons why overpopulation is the biggest and most important issue on Earth, even though this is a rather minor reason). “Anarchy” is taking greater responsibility in order to have greater freedom, to the point where everyone is totally responsible and government & laws are no longer needed and are therefore abolished. Without major mental and spiritual evolution of the human species, this would be impossible even in small hunter-gatherer societies, and is obviously totally impossible in this one. But it’s a good ideal that should be striven for nonetheless.

As to bad human behavior in otherwise good groups — and I don’t count Christianity as one of the “good” groups, monotheistic religions are totally evil for reasons I won’t get into here — it’s not an issue with the group, it’s an issue with humans in general. If that weren’t true, bad behavior as described here wouldn’t exist in groups that purport to oppose that behavior. So looking at the groups is the wrong focus, this problem is much bigger and deeper than that.

@Heidi Hall

I’m sorry to hear what happened to you. While all groups have some amount of hierarchy, Earth First! avoided most of these problems by being a non-membership group. So you couldn’t join, you could just participate and/or campaign. There were no officers or anyone else with titles who were in charge, except that if you did the work to organize and/or run a campaign or event, you’d have more to say about what went on in that event or campaign. This doesn’t totally solve these types of problems, but it’s a large step in the right direction. And it has aspects of anarchism as an additional bonus.

@Mark Behrend

I don’t agree that members of indigenous communities are too busy to philosophize. In fact, quite the opposite is true. Hunter-gatherers only “work” about 20 hours/week, which is at most half of the time that people in agricultural societies work.

Furthermore, traditional indigenous people certainly have philosophies, even if they’re not formalized in the manner that makes them recognizable to you. I know this from direct experience, I have indigenous friends who identify as traditional even though they don’t live on the reservations and live traditionally. And I also know it from other sources. The Aboriginal “dream time” philosophy from what is now Australia and the “spider grandmother” philosophy of the Hopi are as complex as any philosophy in this society, to name just two off the top of my head.

As to calling the cops, I have no problem siccing one thug or group of thugs on another one if I need help. The only other alternatives would be to ignore the harms caused by the thug or to fight back myself. Ignoring people doing or attempting to do harm to me or mine is not the way I relate to or deal with these situations, so that’s not going to happen. Nor am I going to risk going to prison because I shot a thug or thugs. I hate cops too, they’re the army of the rich more than anything and are racist oppressors on top of that, but I’ve called them when necessary because the only other options were not acceptable.

Finally, I don’t agree that those of us fighting for humans living a lot more simply and naturally are “hypocrites.” We didn’t get into this mess overnight and we’re not getting out of it overnight either. We could stop living industrially in 150-200 years if we tried and if we lowered global human population to one billion in that time, but all individuals can be expected to do now is make an effort (I gave up my car over 20 years ago, for example, and mainly use walking, biking, and public transit). These changes will need to come incrementally, because people are not martyrs who are willing to give up all the unnatural conveniences that we were born enjoying and that we therefore expect with all of our consciousness. If you advocate for radical changes like we do, you have to take a very long view and look at the big picture. Calling everyone “hypocrites” doesn’t accomplish anything positive or advance our cause.