“Bring Down the Culture”: An Interview with Kourtney Mitchell

By Vincent Emanuele for Counterpunch

Kourtney Mitchell is a writer and activist currently living in northeast Georgia, United States. He sits on the steering committee for Deep Green Resistance and the national board of directors for Veterans for Peace. Co-author of The Enemy in Blue: The Renatta Frazier Story, he has been involved in social justice activism for eight years. Kourtney is currently AWOL from the Georgia Army National Guard.

***

Vincent Emanuele: Let’s talk a little bit about your background. I know you were born in Illinois and now live in Georgia. What was your childhood like? Was your family politically active?

Kourtney Mitchell: Yes, I was born and spent the first part of my childhood on Chicago’s west side, right in the heart of the inner city. I remember huge gang fights and gun shots carrying on while I was trying to sleep as a kid, and always worrying about getting into fights with neighborhood kids while playing outside with my family. In Chicago, I lived in a three story home where each floor was like its own apartment. I lived with not just my parents and siblings, but also cousins, aunts, uncles, their spouses and my great grandmother, who to this day continues to keep the family together as the virtual matriarch. This is why my family always has and forever will have strong family bonds. Loyalty is natural for us.

We would cross the street to get Chicago-style polish sausages and Italian beef sandwiches, and fries smothered in mild sauce. This was back in the day of corner stores—real corner stores that weren’t attached to gas stations and pharmacies. Up the street the other way was a city park with a basketball court and jungle gym. Even though there was a lot of gang violence in my neighborhood, my family was well-established in the community and for the most part we got along just fine.

In Chicago, we were bussed out of the inner city to a magnet school instead of attending the schools closer to home. Of course I realized the problems with this, but I loved that school as a kid. I can still remember some of my friends, including the sweet little girl who wanted to be my girlfriend after I roughed up a bully who hit her during recess.

As a matter of fact, my grandfather is a former Black Panther in the Chicago chapter. That’s the only thing I know of the political activity of my family. We’ve visited him several times while I was a kid. However, he’s currently in prison in Illinois for charges dating back to his time with the Panthers.

When my mom moved us to Springfield, IL to finish her undergraduate degree, it was a different world. There in the state capitol, we attended mostly white schools where we surprisingly got along just fine and made a whole lot of friends. Schools with enough computers and television screens in the classroom, and decent textbooks. It was in those schools that I was able to write a full romance novel manuscript started when I was ten years old, almost get it published, and appear on Black Entertainment Television for an interview about it. Our middle and high schools were a bit more integrated, and those were the most formative years of my life.

It was in high school that my mother joined the Springfield, IL police department and experienced a lot of racism and sexism, for which she filed a civil suit against the city and settled out-of-court. That whole fiasco was extremely traumatic for my family—we had to move out of the state, and then back to Illinois within a single year. Constant media coverage and negative publicity for my mother and family until it was all settled. Continued harassment from the police department, including an eviction where cops threw all of our belongings out onto the street on my brother and I’s birthday. But we made the most of it. My mother and I wrote and self-published a creative nonfiction book about her experiences.

Vincent Emanuele: The last time we spoke, you were AWOL from the U.S. Army. I remember wanting to escape my unit, but being reluctant because I didn’t have politicized friends or comrades in the military or outside the military. Why did you join the military? And what’s your current status?

Kourtney Mitchell: Technically my status is still AWOL, though I’m working closely with my unit leadership to get the discharge once and for all. The unit was very good to me actually, so I believe them when they say they won’t pursue legal recourse. Answering why I joined the military is tricky. I want to admit right away that I knew better, but… I never should have enlisted.

Okay, so I had returned to Georgia from living and going to school in Missouri, which I still to this day view as a mistake because I had a great community in Missouri and it was hard leaving them. I didn’t like living at home, and I was having a very hard time finding decent work. My family urged me to enlist, so originally I was going to enlist with the Marines, even signed the contract and received a ship date for boot camp. But then I backed out, and went with the National Guard instead. The 68W MOS (combat medic) had a ship date that was too far in the future for my liking, so I decided to join as infantry so I could ship-off ASAP. That was an even bigger mistake than enlisting. Basically, I did it so I could get out on my own again and develop some job skills that may lead to career opportunities. I attended OSUT infantry training at Fort Benning, where WHINSEC (formerly the School of the Americas) trains death squads to squash the resistance in South America.

Vincent Emanuele: Let’s backtrack. At what point did you become radicalized? And who were some of your initial influences?

Kourtney Mitchell: My radicalization started when I was in college. It’s a long but interesting story. I’ll try to keep it somewhat short. My first experience with any kind of radical thought was when I decided to take a writing-intensive course in college that was focused on black female writers. We read Patricia Hill Collins, Toni Morrison, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Alice Walker, Zora Neale Hurston, etc. I didn’t take the course because I thought it was something I should learn about. Honestly, I took it because I needed the writing credit, and the class was available. It turned out to be a very good decision, and it contributed to real change in my life. It helped me establish the basics of feminism as it relates to the experiences of black women.

The instructor offered extra credit for attending a campus community discussion at the Black Culture Center on the representation and exploitation of black women in mainstream media. I shared my thoughts at the event based on what I was learning as a journalism student (later changed my major to sociology), and there was a woman there who really liked what I had to say. She was from the campus Women’s Center, and invited me to join the male ally program. I really don’t know why I agreed to do it; I guess there was something about the course I was taking that got me interested in pro-feminist men’s work, even though I wasn’t articulating it at the time.

I began attending the meetings and actions, and from there I joined the campus peer education program that was focused on anti-violence and anti-sexual assault on campus. That was my training ground—a formal, for-credit course that taught the fundamentals of sexual assault, relationship violence, patriarchy and ending male violence on campus. We were trained in how to help a friend in crisis, as well as how to give presentations to our peers.

That program changed my life forever. The course was extremely intense, at least for a starry-eyed undergrad like me. I remember many nights going home crying because I couldn’t understand how men could be so violent and create such a violent world. I struggled with what I could do as an individual, but I knew that I had no choice but to make pro-feminism my life’s work. I got so many good opportunities—giving presentations to fraternities, football teams, teenagers, college kids, so many different communities. We hosted spoken work events and open-mic nights. It was a fantastic program.

Once I switched my major to sociology, I began learning a bit about Marxist theory, which lead me to anarchism eventually, and then I began reading Derrick Jensen, John Zerzan and Layla Abdel Rahim. Anti-civilization thought revolutionized my thinking of social justice. Now it all made sense. All of the converging crises of racism, patriarchy, and human supremacism now became the overall problem I was trying to name—civilization, namely industrial civilization.

Not long after I returned to Georgia, the Deep Green Resistance book was published, and I began reading voraciously and watching all of the DGR videos online. I attended a workshop that early DGR members gave at a community spot in Atlanta, and I knew that I needed to find a way to join the group after that. I was invited to do so, and from then on my understanding of radical feminism and anti-civ thought has grown by leaps and bounds.

While in college, I got to kick it with Fred Hampton Jr (who pointed me out during his speech because he recognized me, and knew my mom and grandfather), and have dinner with Angela Davis. I saw Maya Angelou, Michael Eric Dyson, Jackson Katz and many others speak on campus. A few friends and I traveled to Jena, Louisiana for the huge Jena 6 protest, and I attended and helped organize several protests and marches on campus, including Take Back The Night marches, as well as a march and occupation of the student commons when legislators were threatening to repeal affirmative action programs. There was also well-attended community forum events for different incidents, such as when some white students thought it was funny to dump cotton balls on the lawn of the Black Culture Center.

Vincent Emanuele: In the past year, the intersection of race and policing has become one of the most galvanizing issues of our time. As a black man living in a nation built on the genocide of indigenous peoples, African slavery and white supremacy, how do you understand, process and resist within this culture?

Kourtney Mitchell: Understanding and processing what is happening in this culture is an ongoing process for me. I’m still fairly new to activism; most of my time was spent as an educator, with only a handful of real on-the-ground actions under my belt. But I guess I understand and process by being an avid reader, listening to pretty much every interview, speech and lecture I can find and/or attend in person, and constant conversations with other activists. As far as racism and white supremacy go, well that’s just a daily grind. My family has experienced both overt and covert racism. My family’s living conditions in Chicago were a direct result of racist housing practices. I mentioned the craziness with my mom at the police department in Illinois. And being followed and stopped all the time for just walking here in Georgia is so normal for me that sometimes I forget it’s not how it should be.

The processing part is the hardest, though, even harder than resisting. Processing is an internalization of what is happening, and it affects my very soul. Truthfully, I sometimes sit in my home, contemplating all of the police murders of unarmed people of color, their rape of women and all of the other craziness happening with policing and I just cry. That coupled with the destruction of the natural world, and it’s all just too much sometimes. But it’s a process—eventually I come out of despair even stronger and more determined. I am extremely privileged to be connected to several very large activist communities. I have a lot of allies, so I have it easier than someone who’s trying to navigate this culture alone.

Some people may not know this, but my family is military and police officer heavy. So I get a heavy dose of both perspectives every day, both against and for this culture. Again, I consider it a privilege, because I get to really hone my analysis on a real-world level.

Resisting this culture has become a calling for me, a purpose for living. I’ve attempted to set out on my own, drop all of my responsibilities and live a nomadic anarchist lifestyle, but that didn’t go well, and just thoroughly upset all of my loved ones. I began realizing that collective action, joining together as an oppressed group of people, is how we effectively resist the empire. So joining DGR and Veterans For Peace has become how I am able to leverage my skills, knowledge and passion for more effective actions. I also don’t mind using all of the tools at our disposal, even though many may say we’re hypocrites for using technology or finding ways to work within the system. I think Derrick Jensen is right when he said that we need it all, whatever skills people can bring in whatever capacity. We need it all to resist.

Vincent Emanuele: Right now, I know you’re a member of two organizations: Deep Green Resistance and Veterans for Peace. Can you talk about these organizations? What are you currently working on?

Kourtney Mitchell: DGR is the first activist organization I joined once I left Missouri and joined my family in Georgia. I was feeling isolated as an activist, partly because I wasn’t able to get to Atlanta consistently, which is where the majority of the activism in Georgia happens. So joining DGR was really a saving grace for me.

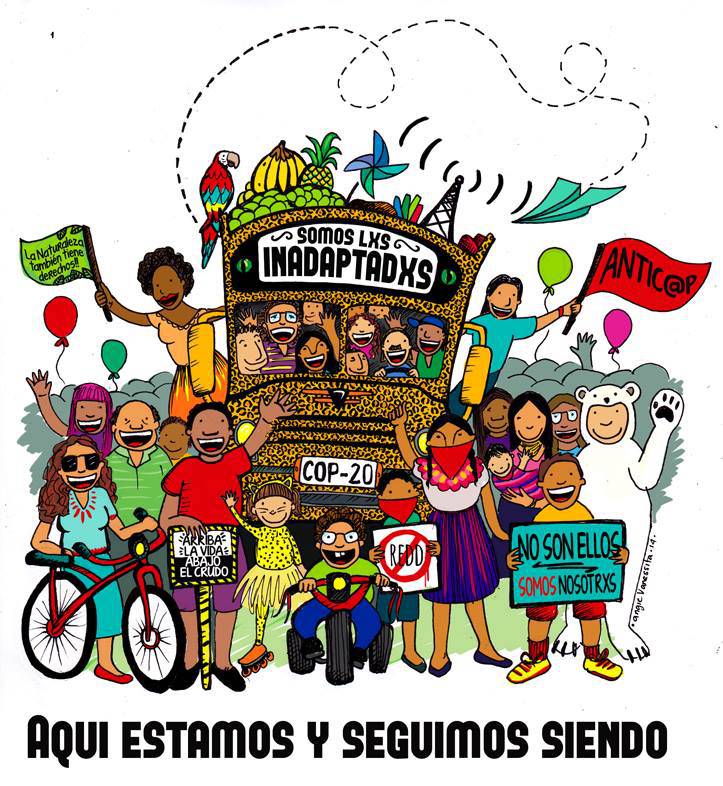

So DGR is a grassroots, volunteer-run social justice organization with chapters all over the world. Our analysis is that industrial civilization is currently killing the planet and oppressing living communities. Unless we bring down this culture—that is, unless we stop all extractive processes and dismantle all oppressive institutions, then the culture will keep going until it has literally killed every living being on the planet. So our strategy is Decisive Ecological Warfare, in which we advocate for the formation of a hypothetical underground militant movement that can attack industrial infrastructure and thus lead to the collapse of industrial civilization. We are not a part of, and do not ever wish to be a part of any kind of underground that may form to this effect. But we loudly and vocally speak in favor of such actions, because we believe it’s the only hope our planet has for survival. Our members engage in nonviolent civil disobedience, as well as widespread educational and activist campaigns around the world. Those killing the planet will not ever stop by asking them nicely. They will only stop when we force them to do so.

Veterans For Peace is a 501c3 non-profit activist organization composed of hundreds of chapters around the world. We are a military veterans-led organization with non-veteran associate members, and one of just a few veterans-led organizations that loudly and vocally opposes all wars and foreign interventions around the world. Our mission is to expose the true cost of war and militarism, and to advocate for reparations to both civilian communities affected by war and for veterans who carry the scars and moral injuries of war.

With DGR, I currently sit on the Steering Committee, the People of Color Caucus and I am the anti-racist editor for our News Service online. I’m involved with several projects as well, including art and music, pro-radical feminism, and I help direct security for the organization.

I currently sit on the National Board of Directors for Veterans For Peace, and I’ve joined the Nominations Committee to help recruit young veterans to the organization and encourage Post-911 veterans to take leadership positions. I also am hoping to do work with our G.I. Resistance working group to encourage young veterans to consider Conscientious Objection or other forms of resistance to military service, and to offer assistance to those who already have. Being AWOL myself, I understand the importance of having a close, loving community to assist in this struggle.

Vincent Emanuele: How has a “deep green” vision and understanding of patriarchy/male violence influenced your approach to strategies, tactics, and so on?

Kourtney Mitchell: As I mentioned earlier, the anti-civilization perspective revolutionized my understanding of social justice. It brought together all of the social problems that were important to me and put them under a big umbrella of civilization as the cause. The “deep green” perspective is really the foundation of this approach.

So it’s easiest to understand what the deep green perspective is when you contrast it with what we like to call “bright green” environmentalism. Bright green is what you get when capitalism attempts to paint what it is doing to the planet with the brush of consumer choices. So corporations and governments want us to think that it’s our fault that the planet is warming and the oceans are dying, and the top soil is blowing away in the wind. They want us to think that it’s because we aren’t buying the right products—our light bulbs, toilet paper, plastic shopping bags, our vehicle emissions, etc. They want us to believe that if we just buy and use the right products, then we can stop the destruction of the natural world, purely by consumer product choices alone.

To go along with this, so-called environmentalists have completely bought into this elaborate and well-funded lie. Even huge organizations like Greenpeace, The Sierra Club, etc, have touted the good of making better consumer choices. Capitalism has completely co-opted the environmental movement, which used to be about actually protecting the natural and is nowadays more about perpetuating industrial economies.

The bright green perspective has a fatal, fundamental flaw: it’s not the products of industrial civilization that are the problem, it’s the industrial economy itself. As a matter of fact, only as high as 20% of all energy and resource use comes from municipalities, and usually that number is much lower. The other 80-90% of all resource depletion and pollution comes from militaries, governments and corporations. The United States military is the world’s largest polluter, dumping more toxic waste into the environment than the top five corporations combined. Someone please tell me how my buying florescent light bulbs and recycled toilet paper is going to stop the military from committing this atrocity?

The deep green perspective takes this radical approach: Earth is a living, breathing being, which sustains homeostasis and provides the very foundation of life. All extractive processes, regardless of what products result, are detrimental to the health of the planet. The industrial economy is completely at odds with life on the planet, and since this is the case without a doubt, then it is the industrial economy that has to be dismantled. Green technology, such as wind turbines and hydroelectric power and solar power, all require industrial extraction, and thus cannot be considered sustainable.

The deep green analysis recognizes that for 99% of our existence on this planet as human beings, we lived in harmony with the land. We had a close physical and spiritual relationship with the web of life on earth, and our communities were set up to directly provide for real human and animal needs, not the needs of cities and empires. Our only hope for survival on this planet is to bring down the culture that’s killing it and return to our humble, close relationship to the land.

Vincent Emanuele: Since being involved, what are some of the pitfalls you’ve seen within the movement? In other words, how could groups and individuals better organize communities?

Kourtney Mitchell: The most obvious thing to me, at least for the environmental movement, is to give up the idea that so-called green technology will save us from certain destruction.

Other pitfalls include the failure of privileged activists to join in a material way the movements that oppressed people have created. There is too much sidelining by men who call themselves pro-feminist, or by whites who call themselves anti-racist. Oppressed groups need your material solidarity, not just your words. Oppressed groups need folks to join the front-lines of resistance, to put our bodies in between the oppressors and the communities they intend to oppress. In the DGR strategy, we recognize that only very few resistors will do the dirty work of materially dismantling the culture using militant means. The rest of us need to do radical actions including nonviolent civil disobedience and loud, vocal, and public advocation of radical strategy, normalizing resistance in the culture and attempting to counter the hegemonic messages of the empire.

I think there’s a lot of good organizing going on, but I just wish there was more cohesion, more collaboration across movements. This is hard when men in various movements refuse to check their male privilege, and refuse to call out male activists who are sexist or have a history of violence against women. And it’s hard when whites in various movements refuse to undergo the hard transformational process of admitting to and dismantling their own racism. That silence needs to stop right now. We don’t have time for half-assed activism. We need effective actions that can actually challenge power, dismantle capital and overthrow the power structure.

I think we should start adopting a process-oriented approach. What I like so much about the DGR strategy is that it recognizes that each action has a place in the movement, and that each action has to be evaluated on its ability to reach intended goals.

So growing community gardens alone cannot stop pipeline construction, nor can it stop Monsanto. But it can help feed activists. Such an action can sustain the movement. Actions such as hypothetically attacking oil infrastructure can actually lead to the collapse of the system, so that’s considered a decisive action. We have to analyze actions in this way, otherwise we’ll always be fighting a losing battle against an enemy who has vastly more resources and has a monopoly on violence.

Finally, I think activists overall need to understand that our goal should be to dismantle the culture entirely, not simply just to feel good about our actions. Feeling good is not the point when people of color (POC) are still being murdered in the streets; men are still killing and raping women; and indigenous communities are still being wiped off the planet. We need to get over our reliance on nonviolence as an end goal, and speak honestly about what it will actually take to win this war.

Vincent Emanuele: What is your vision for the future? Here, if you would go into some detail, that would be great, as I think people are interested in alternatives.

Kourtney Mitchell: Well, I can’t say that I personally have a vision for what the entire world needs to look like in the future. Personally, I want to possibly raise kids, grow food, tend to animals and live in a loving, supportive community away from industrial infrastructure. I want a sustainable off-the-grid lifestyle for my loved ones. But the way this culture is going, that may not ever be possible.

I can say that since civilization is a monoculture—that is, it is a culture characterized by the growth of cities, and that cities are proliferating all over the world, demolishing other forms of living such as tribes, clans, bands, etc—and that civilization behaves in a way that says only it can exist in the world, I think what could be of value is the proliferation of a diversity of cultures. A diversity of living arrangements tailored to the specific land-base that people find themselves living on. Our social structures, our communities, must be intimately tied to the specifics of the land we live on, so that we can live in such a way that actually contributes to the land, that actually benefits the land, instead of destroying it. Whatever that looks like for different communities, I welcome that future.

I think that inevitably means we must give up on all extractive processes, including agriculture. Many people do not understand just how harmful agriculture is to the land. This method of growing food has been characterized as the worst mistake humans have made in our history. Agriculture relies on annual mono-crops that actually destroy the land. What we need to rediscover is the perennial polycultures that give back to the land, and that cultivate the other lifeforms on the land. Agriculture has lead directly to our skyrocketing human population that is set to crash pretty much any decade now. Agriculture has to grow more food to feed more people, which in turn leads to more people and thus requires more food. It’s a never-ending cycle, and it’s really the most horrific consideration of our future. We need to be smart about how to address the population problem, starting with emancipating women around the world towards autonomy over their bodies and families.

Vincent Emanuele: Who are some of your personal influences?

Kourtney Mitchell: Oh goodness, too many to name them all. Really, my activism has consisted mostly of repeating what a lot of good people have said and done before me.

Some of my most influential comrades are dear close friends of mine, such as the seasoned activists in DGR and VFP. Saba Malik, Derrick Jensen and Lierre Keith have had the most influential impact on my activism. My mother continues to be my biggest inspiration for overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds to become successful and instill her family with a sense of pride and purpose. The work of Gail Dines has been absolutely huge for my understanding of the evils of the sexual exploitation industry. Michael McPherson of VFP is a prime role model of mine, and I greatly admire his work both within the organization as well as his longtime work with some of the nation’s biggest anti-police violence movements. Doug Zachary, who’s a member of both VFP and DGR, is an incredible pro-feminist man and war resistor. He had the biggest impact on my decision to get involved in the anti-war movement.

Vincent Emanuele: What are you currently reading?

Kourtney Mitchell: The Culture of Make Believe by Derrick Jensen, who pulls no punches in his analysis of the dominant culture, and that makes his reading pretty tough to get through. It took me over two years to read both volumes of Endgame, but I’m glad I did. Derrick is a talented writer who has the ability to grab the attention of even his most ardent detractors. If you don’t feel like resisting with all of your might after reading his work, then you really don’t have a pulse.

Also, I’m reading Radical Acceptance by Dr. Tara Brach. I’ve been into Buddhist meditation and spirituality since 2006 and it gives me a good balanced perspective on the human condition and the nature of suffering in this world. I like how Dr. Brach weaves her personal narrative into a transformative program for overcoming our self-loathing. Probably the most practical Buddhist book I’ve ever read, which is saying a lot because I’ve often felt my spirituality and my activism weren’t meshing as well as I would like.

Vincent Emanuele: Any closing remarks or suggestions?

Kourtney Mitchell: In the words of Andrea Dworkin: Resist! Do not comply!

Vincent Emanuele is a writer, activist and radio journalist who writes a weekly column for TeleSUR English. He lives in the Rust Belt and can be reached at vince.emanuele@ivaw.org

From Counterpunch: http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/02/27/a-feminist-radical-environmentalist-and-awol/