by DGR News Service | May 25, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

An upcoming episode of The Green Flame podcast will focus on answering listener questions. Do you have questions for us? Want us to break down an issue that is bothering you, or that you want clarification on? What are you wondering about Deep Green Resistance, our analysis, our work, or how to get involved? This is a good chance to get answers.

Here’s how to submit your questions:

About The Green Flame

The Green Flame is a Deep Green Resistance podcast offering revolutionary analysis, skill sharing, and inspiration for the movement to save the planet by any means necessary. Our hosts are Max Wilbert and Jennifer Murnan.

Subscribe to The Green Flame Podcast

by DGR News Service | May 23, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

This excerpt is from Derrick Jensen’s unpublished book “The Politics of Violation.” It has been edited slightly for publication here. The book is in need of a publisher. Please contact us if you wish to speak with Derrick about this.

By Derrick Jensen

For more than two thousand years, a war has been waged over the soul and direction of anarchism.

On one hand, there are those who understand the straightforward and obvious premises that at least to me form the foundation of anarchism: that governments exist in great measure to serve the interests of the governors and others of their class; and that we in our communities are capable of governing ourselves.

And on the other hand, there are those who argue that all constraints on their own behavior are oppressive, and so for whom the point of anarchism is to remove all of these constraints.

I researched and wrote this book in an attempt to understand this war, in the hope that understanding this war can help us understand how and why anarchism has become a haven for so much behavior that is community- and movement-destroying; how and why a movement claiming to show that humans are capable of self-governance so often seems to do everything it can to show the opposite; how and why a movement that claims to be about ending all forms of oppression can be so full of bullying, abuse, and misogyny.

If we all understand this, might we as a society move both anarchism and the larger culture away from these behaviors and toward more sane and sustainable communities?

It became clear to me, however, that the book is about more than anarchism. In part it’s about differences between understanding and learning from a political philosophy—any political philosophy—and turning that philosophy into an identity; what happens when the former ossifies into the latter. This is a problem not just in anarchism but in more or less all philosophies.

When Harm is Left Unchecked

A strength of anarchism is that many anarchists are willing to struggle for their beliefs, and to fight power head on. A weakness is that too many anarchists are too often not strategic, tactical, or moral in choosing their fights, including how they will fight, and in choosing the targets of their attacks.

Severino di Giovanni provides a great example from the 1930s. He was an anarchist in Argentina who started a bombing campaign targeting fascists and also, because of the killings of Sacco and Vanzetti, bombing targets associated with the United States. We can argue over whether his actions were appropriate. And the anarchists in Argentina certainly did argue over it, which leads to why I bring him up: one of the anarchists who spoke against his bombing campaign (saying it would lead to a right wing coup, which in fact happened soon after) was murdered.

Guess who was the prime suspect in his murder?

…

I could provide hundreds of examples of atrocious behavior that have become normalized among too many anarchists. For that matter I could provide hundreds of examples that have happened to me, from threats of death and other physical violence to the posting to the internet of pictures of me Photoshopped to simulate bestiality. Probably the most telling action has been that anarchists arranged for my elderly, disabled, functionally-blind mother to receive harassing phone calls every fifteen minutes from 6:30 a.m. to 10:30 p.m. for weeks on end.

The point isn’t that they did this to me (and my mother): I’ve known too many people who’ve received their own version of this treatment.

Part of the point is that some people are terrible human beings. Change a few details, and anyone could tell similar stories from most other movements or organizations. And so this book becomes a case study of some of the harm terrible human beings can, if left unchecked, do to movements.

So, generically: What sorts of terrible people does your movement/organization support? And what harms do these people cause? Ecofeminist Charlene Spretnak has written extensively on social change movements, and has talked about how abusive behavior drives away people, especially women, in “huge numbers. That’s a brain- and talent-drain these movements cannot afford.”

What can we do about that?

An Insult to One is Injury To All

Here’s another example of the sort of community-destroying behavior that has come to characterize too much anarchism. A few years ago, I was discovered by the Glenn Beck arm of the right wing. Within two weeks I’d received literally hundreds of death threats from them, many of which were highly detailed in what was to be done to me (e.g., photos of castration) and in information about where I live, my schedule, and so on. In response to these threats I bought a gun and installed bars over my doors and windows. I also called the police and the FBI. I didn’t believe the police and FBI would be particularly helpful (they weren’t), but I wanted for there to be an official record of the threats for two reasons. The first is that on the remote chance someone did kill or injure me, people would at least have an idea where to start looking for the perpetrators. The second is that if someone attempted to harm me and I had to use lethal force to protect myself, it would already be a matter of public record that I had reason to fear for my life. I could imagine a court scene playing out after I was charged with murder for killing someone who had attempted to kill me.[1]

The prosecuting attorney asks, “Were you afraid for your life?”

“Yes.”

“Did you call the police?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

A long silence while I consider that it wouldn’t be particularly useful to say I didn’t call the police because to do so is evidently against anarchist ideology.

The prosecuting attorney continues, “Then I guess you weren’t very afraid, were you?”

Trial over. I lose.

The point is that when I told my neighbors I’d received death threats, they responded as you’d expect decent human beings to respond—with sympathy and expressions of concern for my safety. Some took tangible steps to help guarantee this safety. For crying out loud, a member of the local Tea Party helped me install the bars. This is what members of a community do. An insult to one is an injury to all, remember?

On the other hand, with few exceptions I received little positive support from anarchists, who instead accused me of making up the threats, called me a coward for paying attention to them (many of these particular comments were, ironically enough, anonymous), threatened to kill me themselves, or excoriated me for calling the police.[2] Anarchists quickly labeled me a “cop lover,” then “pig fucker,” then “snitch,” then “someone who rats out comrades.” Soon, anarchists were accusing me of “regularly working with the FBI and the police,” and of being a “paid police informer.” It wasn’t long before some were saying, “Word on the street is that he’s been a fed from the beginning. They wrote all his books.”

To Distort is To Control

How does a political philosophy that leads people to act as did those young men I described who became bodyguards for the victim of a sexual assault lead others to act so despicably? How can anarchism be so easily and forcefully used, as it has been, as an excuse for men to sexually or otherwise physically assault women? How can anarchism be so easily and forcefully used to support, as we’ll see, the sexual abuse of children? And how can we prevent all of this from happening in the future?

Can anarchism be fixed?

We should ask these questions of every social movement. This questioning is especially important for those who are inside these movements.

Change a few words, and this book could have been written about almost any social movement or group. I know female Christians (now former Christians) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male Christians, and then pressured by the Christian community not to go to the police because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

I know female soldiers (now ex-military) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male soldiers, and then pressured by the military community not to go to the police because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

I know female athletes (now former athletes) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male athletes, and then pressured by the local athletic community not to go to the police because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

I know female police officers (now former ones) who’ve been sexually assaulted by male police officers, and then pressured by the local police community not to go to the police (!!) because to do so would supposedly harm their community.

Substitute the words musicians, teachers, loggers, environmental activists, actors, writers, and the story is the same.

So this book provides an exploration of what rape culture does to movements, and how movements are deformed or destroyed by the imperative to violate that is central to patriarchy, central to the dominant culture.

I’ve long been a critic of Christianity, but I can’t tell you how many times, especially when I used to drive beaters (I bought four cars in a row for one dollar each, and considered these good deals since the cars must have been worth at least twice that much), that I’ve been stuck by a road, and the person who stops to help fix my car has been a Christian stranger, motivated by a calling to do good in the name of their belief system. Yet, Christianity has been and still is used to justify—and leads to—atrocious behavior such as gynocide, genocide, ecocide. When I think of Christians, I think of a wonderfully kind man and woman who invited me into their home when I was living in my truck in my twenties. And when I think of Christians I think of misogynistic, racist, pro-imperialist buffoons. I think of Christians rationalizing slavery, rationalizing capitalism. I think of Christians burning women they considered witches, burning Native Americans, burning the world. I think of Christians burning other Christians. How does a religion that leads to wonderful people like the couple who gave me a place to stay also lead to such routinely atrocious behavior?

Likewise, when I think of the American Indian Movement, I think of brave women and men standing up to the United States government and to corrupt tribal governments. And I think of misogynist murdering assholes raping and killing Anna Mae Aquash, among others.

When I think of the Black Panthers I think of free breakfast programs for children and black pride and protecting neighborhoods from police violence. And I think of systematic programs of rape by male Panthers against women both black and white.

I’m sure you can find your own examples.

What is wrong with these movements?

Justifying Oppression

Obviously, anarchism is not the only philosophy that has been used to rationalize or facilitate the sexual exploitation of women. We’d be hard-pressed to find philosophies within patriarchy that haven’t. And certainly, groups other than anarchists have facilitated this exploitation. Organizations from the police to the courts to the military to churches to universities to professional sports organizations to the NCAA to the music industry to the Boy Scouts to pretty much you-name-it have facilitated or covered up sexual assaults by men on women or children.

Those of us who care about stopping atrocities need to ask: How does any particular philosophy justify or otherwise facilitate atrocious behavior? And what are we going to do to stop these atrocities?

Panem et Circenses

I became interested in anarchism when I first became politicized—that is, when I began to understand that, as economists are so fond of saying and even more fond of then ignoring, there is no free lunch. In other words, all rhetoric and rationalization aside, the wealth of some comes at the expense of others.

In other words, empires require colonies.

It immediately became clear to me that while much of how a state disperses resources (e.g., time and money) could be perceived as citizen maintenance,[3]—or, with thanks to Juvenal, providing enough “bread and circuses” to keep the exploited from tearing out the throats of the rich—the state’s most important function by far, and the primary reason for its existence, is to take care of business; that is, to take care of the interests of those in power.

Burden of Proof

So there’s a sense in which the bad behavior of too many anarchists is not only appalling but tragic, Bad behavior among anarchists represents thousands of years of lost opportunity for meaningful social change, because while some anarchist analysis makes sense, the behavior of too many of those who call themselves anarchists can get in the way of people wanting to share a movement with them.

The sensible analysis begins with this: The state isn’t necessary for human survival, and in fact the state primarily serves the interests of the governors and others of their class.

If you don’t believe governments primarily serve the interests of the governing class, ask yourself if you believe governments take better care of human beings, or of corporations. If governments had as their primary function the protection of human and nonhuman communities, would they devise a tool—the corporation—that exists explicitly to privatize profits and externalize costs, that is, to funnel wealth to the already wealthy at the expense of others? I’ve asked tens of thousands of people all over the United States and Canada if they believe governments better serve humans or corporations, and no one ever says humans.

Let’s throw in a couple more common-sense comments about anarchism. The first is by the American linguist, philosopher, scientist and activist Noam Chomsky (who, by the way, is also hated by many of the anarchists on the wrong side of the war for the soul of anarchism, who call him “a pussy” and “the old turd”): “That is what I have always understood to be the essence of anarchism: the conviction that the burden of proof has to be placed on authority, and that it should be dismantled if that burden cannot be met. Sometimes the burden can be met. If I’m taking a walk with my grandchildren and they dart out into a busy street, I will use not only authority but also physical coercion to stop them. The act should be challenged, but I think it can readily meet the challenge. And there are other cases; life is a complex affair, we understand very little about humans and society, and grand pronouncements are generally more a source of harm than of benefit. But the perspective is a valid one, I think, and can lead us quite a long way.”[4]

Makes sense, right?

Now let’s throw in another, by Edward Abbey: “Anarchism is not a romantic fable but the hardheaded realization, based on five thousand years of experience, that we cannot entrust the management of our lives to kings, priests, politicians, generals, and county commissioners.”[5]

This all seems pretty obvious, and leads to the question, why aren’t more people anarchists?

[1] And most of us have read accounts of this sort of thing, for example, so many of the women in prison for killing their abusive husbands. In the town where I live a woman is right now being charged with murder for shooting her husband in front of witnesses who all swear that he routinely beat her, that this night he was punching and kicking her, and just before she shot him he yanked her by her hair out of a car as she was attempting to escape. Even the dead man’s mother is begging prosecutors to drop the charges.

[2] This whole question of never speaking to the police cuts to the heart of one of the problems with too much anarchism. Just as with any rigidified ideology, the ideology itself comes to supplant circumstance and common sense. For example, when attorneys advise you never to talk to the police, they mean when you’re under suspicion, not under every circumstance. If anarchists saw Ted Bundy knock out a woman, load her into his car, then drive off, they wouldn’t call the cops? What are they going to do, hop on their bikes and pedal after him?

[3] Such as providing water and waste disposal for the people. But the fact is agriculture and industry account for more than 90 percent of human water usage and 97 percent of waste production. Governments “take care of” big business under the guise of “citizen maintenance.”

[4] Doyle, Kevin, “Noam Chomsky on Anarchism, Marxism, and Hope for the Future,” Red and Black Review, 1995, http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/rbr/noamrbr2.html – Site visited 6/20/2016.

[5] Abbey, Edward, A Voice Crying in the Wilderness, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1990.

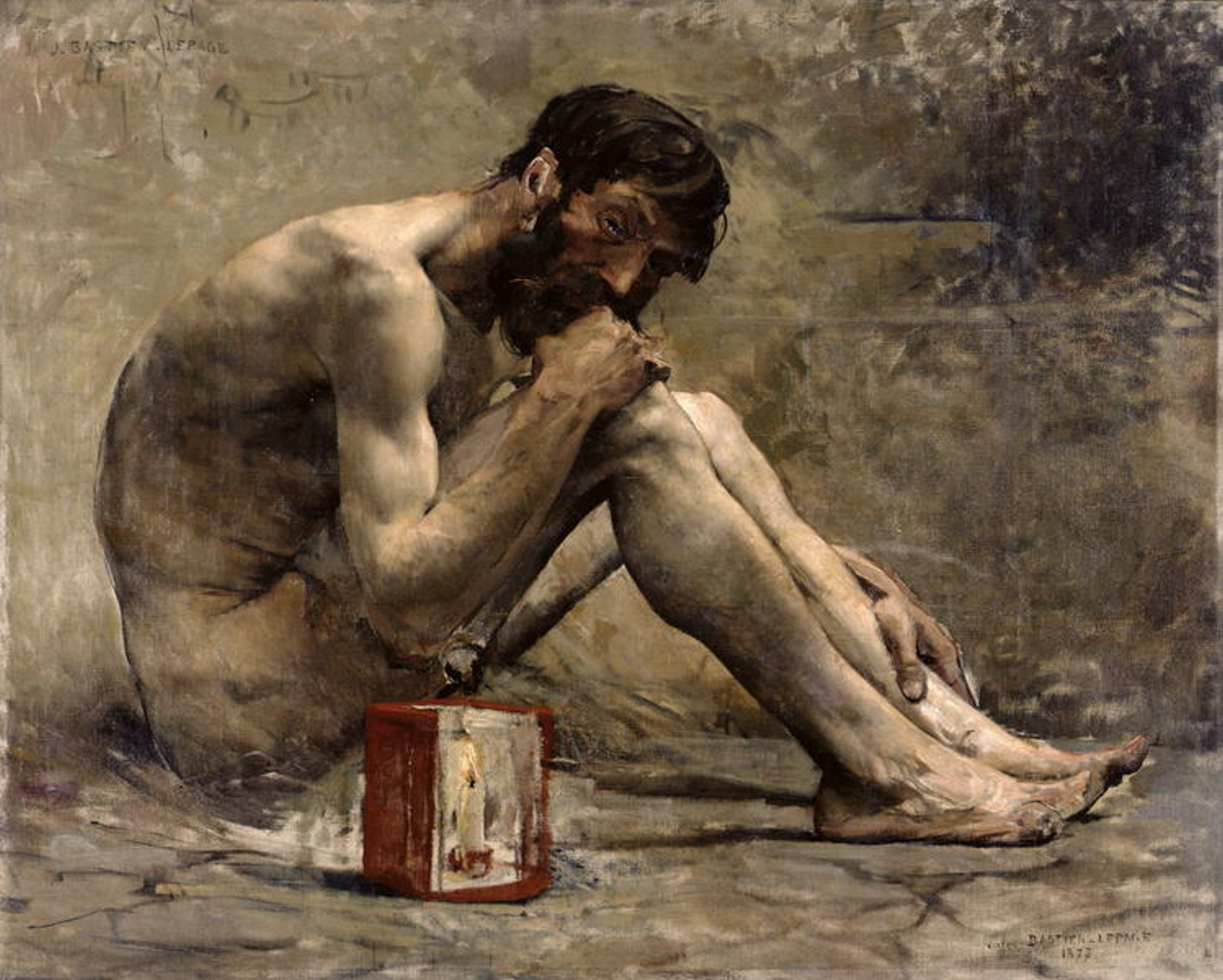

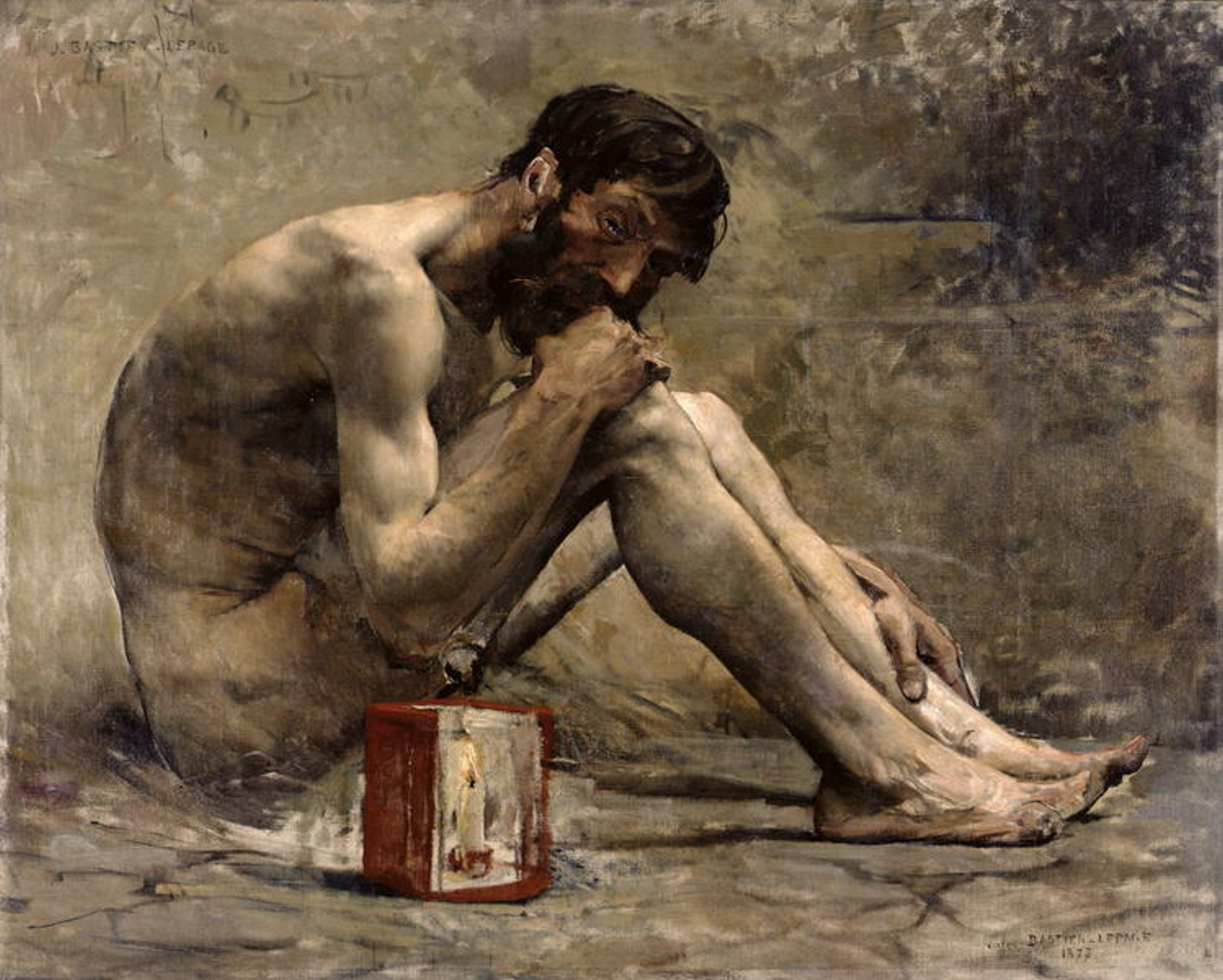

Featured image: 1873 painting of Diogenes, an ancient Greek Cynic and prominent figure in proto-anarchism. By Jules Bastien-Lepage.

About the Author

Derrick Jensen is a co-author of Deep Green Resistance, and the author of Endgame, The Culture of Make Believe, A Language Older than Words, and many other books. He was named one of Utne Reader’s “50 Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World” and won the Eric Hoffer Award in 2008. He has written for Orion, Audubon, and The Sun Magazine, among many others.

by DGR News Service | May 21, 2020 | Male Supremacy, White Supremacy, Women & Radical Feminism

In this excerpt from Ain’t I Woman: Black Women and Feminism, author bell hooks describes the insidious nature of racism and sexism and the links between patriarchy and white supremacy. Understanding this type of analysis is critical to understanding how oppression functions within civilization as a tool of social control. While hooks uses the term “American,” the same analysis applies across much of the world.

Racism and Feminism: The Issue Of Accountability

By bell hooks

American women of all races are socialized to think of racism solely in the context of race hatred.

Specifically in the case of black and white people, the term racism is usually seen as synonymous with discrimination or prejudice against black people by white people.

For most women the first knowledge of racism as institutionalized oppression is engendered either by direct personal experience or through information gleaned from conversations, books, television, or movies. Consequently, the American woman’s understanding of racism as a political tool of colonialism and imperialism is severely limited.

To experience the pain of race hatred or to witness that pain is not to understand its origin, evolution, or impact on world history. The inability of American women to understand racism in the context of American politics is not due to any inherent deficiency in the woman’s psyche. It merely reflects the extent of our victimization.

No history books used in public schools informed us about racial imperialism.

Instead we were given romantic notions of the “new world“ the “American dream.” America as a great melting pot where all races come together as one. We were taught that Columbus discovered America; that “Indians“ was Scalphunters, killers of innocent women and children; that black people were enslaved because of the biblical curse of Ham, that God “himself” had decreed they would be hewers of wood, tillers of the field, and bringers of water.

No one talked of Africa as the cradle of civilization, of the African and Asian people who came to America before Columbus. No one mentioned mass murder of native Americans as genocide, or the rape of native American and African women as terrorism. No one discussed slavery as a foundation for the growth of capitalism. No one describe the forced breeding of white wives to increase the white population as sexist oppression.

I am a black woman. I attended all black public schools. I grew up in the south were all around me was the fact of racial discrimination, hatred, and for segregation. Yet my education to the politics of race in American society was not that different from that of white female students I met in integrated high schools, in college, or in various women’s groups.

The majority of us understood racism as a social evil perpetrated by prejudiced white people that could be overcome through bonding between blacks and liberal whites, through military protest, changing of laws or racial integration. Higher educational institutions did nothing to increase our limited understanding of racism as a political ideology. Instead professors systematically denied us truth, teaching us to accept racial polarity in the form of white supremacy and sexual polarity in the form of male dominance.

American women have been socialized, even brainwashed, to accept a version of American history that was created to uphold and maintain racial imperialism in the form of white supremacy and sexual imperialism in the form of patriarchy. One measure of the success of such indoctrinate indoctrination is that we perpetrate both consciously and unconsciously the very evils that oppress us.

Gloria Jean Watkins, better known by her pen name bell hooks, is an American author, professor, feminist, and social activist.

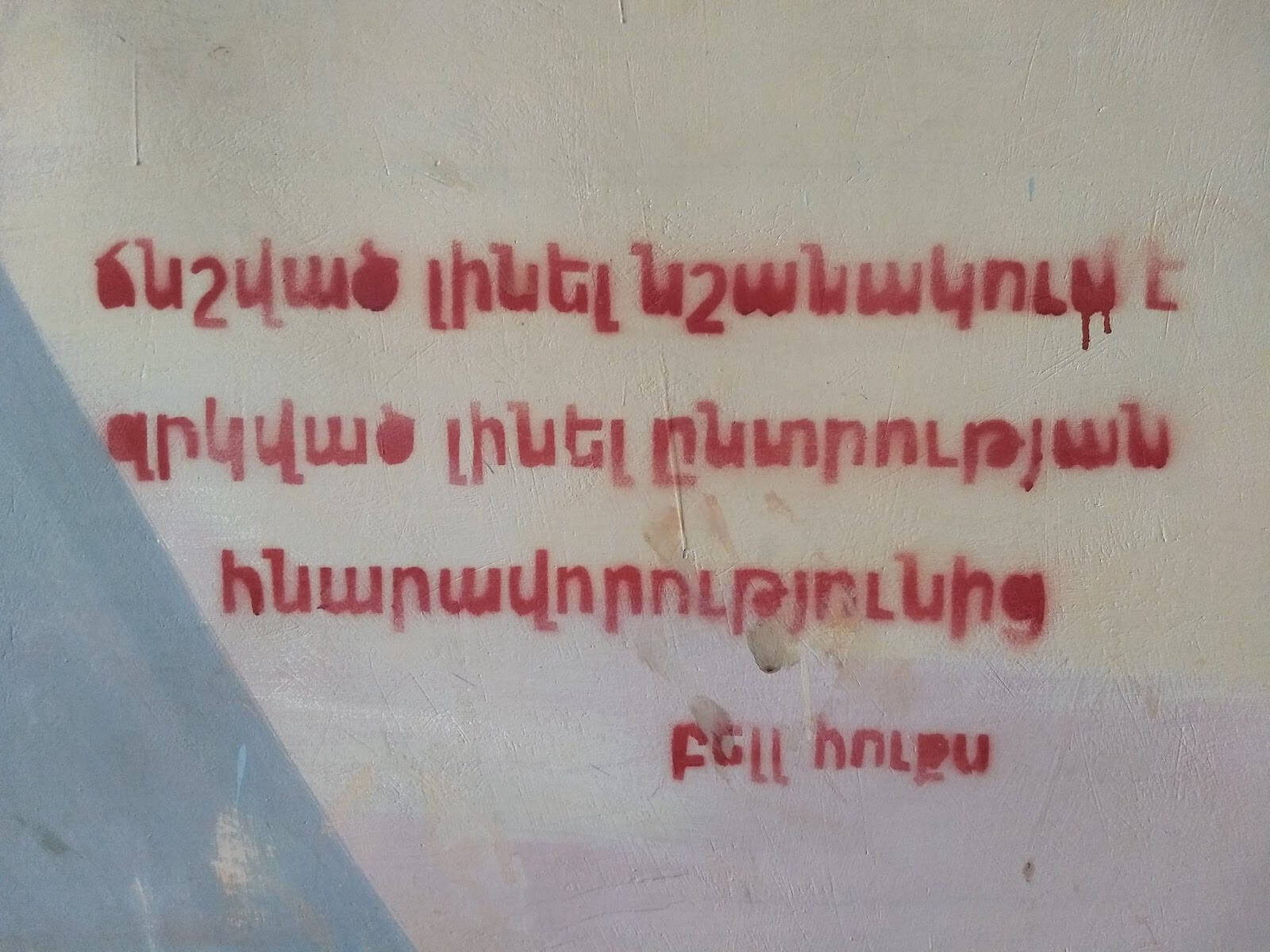

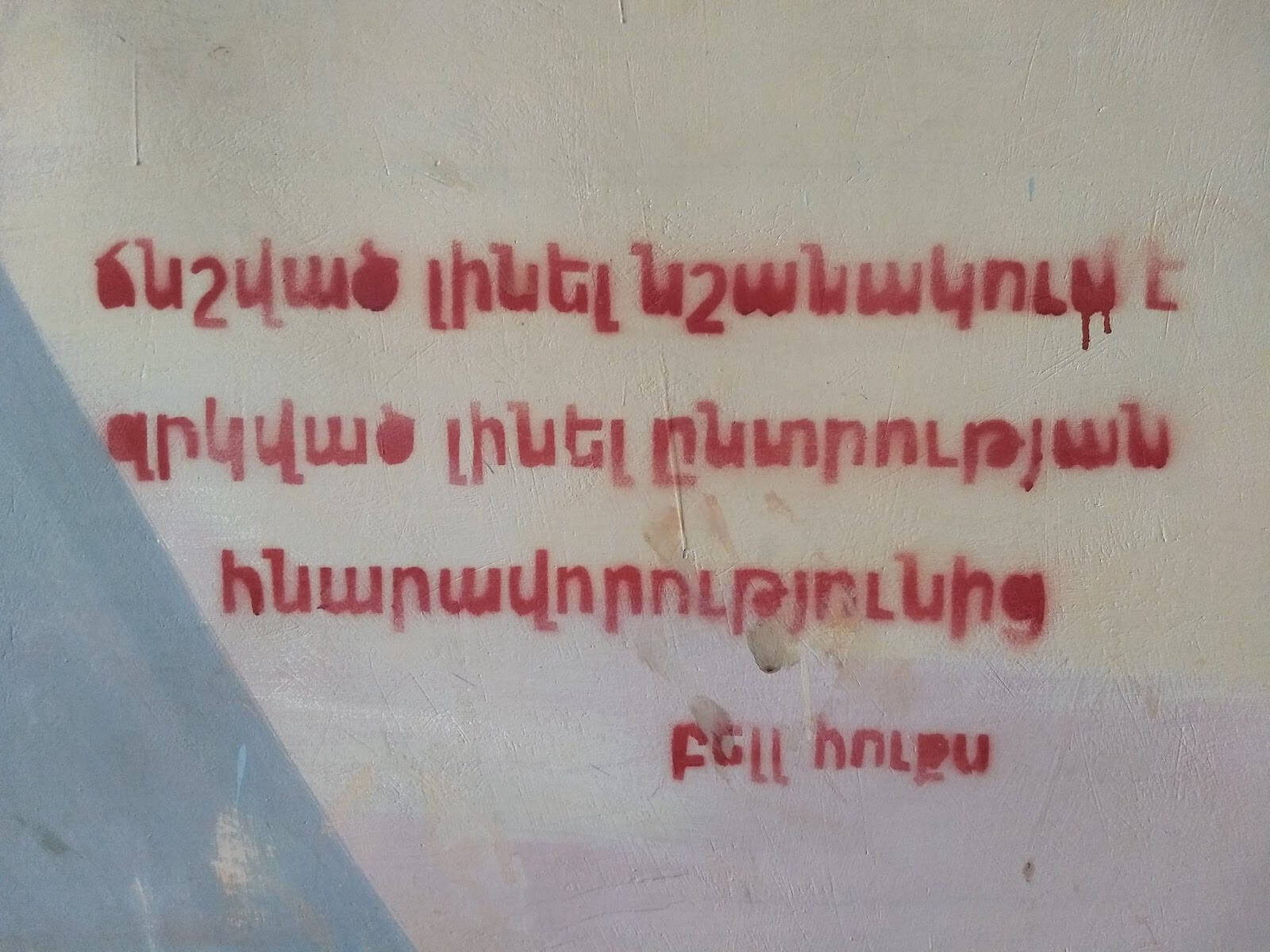

Featured image: Armenian Graffiti in the city of Yerevan. It is a translated quote of the author bell hooks which reads “To be oppressed means to be deprived of your ability to choose.” By RaffiKojian, CC BY SA 4.0.

by DGR News Service | May 19, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

Leadership is incredibly important for resistance movements. Yet many of us mistrust leaders—with good reason. What exactly is a leader? Are there leadership models that align with our ethics? How can one develop resistance leadership skills? This piece, excerpted from internal Deep Green Resistance training materials, explores these topics.

By Fred Gibson

Why Leadership is Important

It’s no secret that resistance to industrial civilization isn’t winning. The planet is still dying, and injustice and oppression are rampant; you might say we’re getting our asses kicked.

In part, our struggles are due to the enormity of the problem, and our small numbers. We have no control over the former, but more over the latter. Consider these issues for a moment:

- Do we have problems with recruitment? Turnover? Commitment?

- Are we all on the same page regarding purpose, direction, and/or strategy?

- Do we experience ‘drama’ / horizontal hostility within our ranks, or across resistance collectives?

- Do you want comrades to struggle with you, to take risks, to actually take direct action, but find the response underwhelming?

It’s not a stretch to suggest that these questions can be addressed by more effective leadership among members of the resistance. It isn’t hyperbole to declare that the planet is crying out for leadership. From John Gardner: “we are anxious but immobilized” by immensely threatening problems. What’s needed is the capacity to focus our energies, and a capability for sustained commitment. This is a call for leadership, of course. We’re at war for the survival of the planet, and we cannot afford not to fight better.

No one has yet figured out how to manage people effectively into battle; they must be led.

— John Kotter

The corporate world and the military invest heavily in leadership development, as they understand the payoff in competitive advantage that leadership capacity brings. They’re organized: we need to be, too. We have to compete and win without traditional leverage (rewards, authority) over others. Comrades need to be led, not managed or coerced.

What is Leadership?

One challenge for us is to choose a conceptualization of leadership with which to work, because embedded in each are assumptions, about: agency with respect to followers or peers; relative worth of comrades vis a vis leaders; acceptability of a hierarchy or power differential; and so on. One conceptualization that fits our requirements comes from Kouzes and Posner:

Leadership is the art [and practice] of mobilizing others to want to struggle for shared aspirations.

This form of leadership fits nicely for us in the resistance. Leadership here is not a position, or about power. This approach also suggests a process of mutual influence, not coercion or manipulation. For resistance members, this ‘egalitarian’ view should be more palatable than management-oriented approaches; at the same time, viewing leadership as a process shared by all avoids a tendency for resistance groups to devolve into cults of personality, which not only limit the existence of the collective to the lifetime of the cult leader, but also tend toward abuse and misogyny.

How then can we practice leadership in this way? By incorporating five “practices” that enable leaders to inspire their comrades to get extraordinary things done.

1. Serve as a Model

(Who are you and what are you all about?)

Effective leaders first “find their voice” – they discover, prioritize, and clarify their values, both personal and organizational. They resolve potential conflicts between their values and those of whatever collective they are part of. Once they have found their voice, leaders ensure they speak in ways consistent with the values of the larger collective, by constantly engaging in dialogue with others concerning what is important, what is not, and why the shared values are necessary for the survival of the collective and realization of its purpose. Clarity and commitment to these values are essential prerequisites for leaders to establish core principles concerning the way comrades, constituents, and allies should be treated and the way goals should be pursued.

Leaders also set the example by behaving in ways that are consistent with shared values. By acting as an exemplar for share values, leaders help comrades see how the values play out in behavioral terms – they teach. By modeling and teaching, leader act to establish and maintain a healthy culture for the group. “Culture work” is a critical leadership function, and all the practices we describe here play some role in influencing the culture of the group.

2. Inspire a Shared Vision

(What do we want our world to be like?)

Resistance leaders need to answer the question, “What are we fighting for?” Collective struggle is fueled by a shared vision of the future – of a realistic, credible, attractive future; an ideal and unique image of the future for a group, organization or larger collective. Leaders envision the future and clearly paint a picture for the group to comprehend.

- Without a vision for a group, little can happen. If a leader is going to take people places they haven’t been before, constituents need to have a sense of direction. This is the function an effective vision provides.

- Leaders look forward to the future. But visions seen only by the leader aren’t enough to make things happen; effective leaders therefore show others how their values and interests will be served by a long-term vision of the future.

The visioning process is enabled by laying the groundwork of shared values.

A vision …doesn’t just reveal itself in a flash of light or a brilliant dream! It evolves from knowledge of ourselves, our values, and our desires.

— Laraine Matusak

The process of creating a shared vision isn’t mystical or forbiddingly charisma-charged; it’s pretty straightforward.

- Know yourself & your organization (or similar groups) – and know the past. Visit the past of your group or your movement to better understand the possible futures.

- Get in touch w/your organizational values. Determine what you want to fight for.

- Let yourself dream/get creative.

- Enlist others in the vision – attract people to a common purpose (discuss it, articulate it, repeat it) by appealing to shared aspirations. Demonstrate your belief and confidence in it, and in the ability of your comrades to achieve it.

Just because your organization has a vision in place doesn’t imply you can’t undertake this important work for whatever part of the organization you’re leading. Your comrades may be hungry for direction and meaning – feed that need.

3. Challenge the process

(What should we do differently?)

We don’t have to tell resistance warriors they need to challenge the status quo (dominant culture), as that’s likely the path that led them to resistance work in the first place. Continue to do that! But it’s less likely these same advocates for fundamental, radical change in the world apply that analysis internally, to their own groups or organizations. Give yourself permission to voice the need for changes, wherever they might be needed. We doubt your group is perfect, so do yourself and them a favor and help them move in the direction of improvement and evolution.

Search for opportunities to change your status quo, because comrades do their best when there’s the chance to transform the way things are. Seek challenging opportunities to test your abilities, and motivate others to exceed their self-perceived limits. We’re not going to make a dent in the dominant culture by doing business as usual, in the larger society or in our respective groups. We must be vigilant for opportunities to change our comrades, our groups, and ourselves. Look for innovative ways to change, grow and improve. To maintain energy and momentum as part of the change process, one thing leaders can do is treat every assignment as an adventure, not just another routine. Even in the resistance world, there are lots of tasks that are less than romantic. Look for ways to keep yourself and comrades engaged as much a possible, and open to suggesting change.

Continue the drive to change and evolve by experimenting and taking risks, by trying new ways of reaching toward the mission and purpose. To that end, constantly generate small wins (incremental successes linked to innovations they or others are trying) and learning from the resulting mistakes, too.

You don’t have to be the creator or innovator – you can recognize and support good ideas, and challenge the system to get them adopted; you can be a champion of risk takers. Create a climate for learning, taking risks, and changing.

4. Enable Others to Act

(How can I help you resist?)

You may need to “decolonize” your mind. Effective resistance efforts won’t be led by the strong loners of our neoliberal movie mythology; they will be led by activists who encourage comrades to thrive in their work. Leaders can’t succeed alone. They create and maintain trustworthy relationships, and build cohesive teams that feel like family. But while good leaders don’t try to do everything by themselves, they don’t just delegate, either; they involve comrades in planning and give them discretion.

Leaders foster collaboration by promoting cooperative goals, facilitating relationships and building trust.

Trust is a core component of collaboration and nurturing effective groups. ’We’ can’t happen without trust. It’s the central issue in human relationships. Without trust you cannot lead. Those who are unable to trust others fail to become leaders, precisely because they can’t bear to be dependent on the words and works of others. From the comrades’ perspective, why should a fellow resistance warrior work hard or take on risk for someone she or he doesn’t trust? Make sure you create a climate of trust – here are some tips:

- Be the first to trust. Model the way!

- Show concern for others (often, by listening)

- Share knowledge and information. Sure, information is power, so share it!

Another best practice for fostering collaboration is to promote joint efforts in staffing tasks or campaigns, and incorporate systems that enable fact-to-face interactions wherever possible. Resistance members are spread far and wide, so it’s difficult to implement these interactions physically, so use what’s available. Technology is evil, but let’s leverage it to build an effective resistance while we can.

Effective leaders continually develop comrades and cultivate their confidence and self-efficacy. They strengthen others by sharing power and discretion, and by delegating with development and challenge in mind. A comrade may not be as good as you in a particular area, but that doesn’t mean you can’t delegate that task to him! Let them do their best and grow from the practice and feedback. Sharing builds competence and confidence as well as trust. It’s a powerful practice.

Generate a learning climate and educate others in other ways, too. Be a coach.

- Give constructive feedback, particularly when a comrade completes something you delegated to her or him.

- Probe a comrade for her understanding, reflection and learning following a challenge. Engage in Socratic questioning to further a comrade’s ability to reason and reflect.

Don’t try to do everything yourself – spoiler: you can’t. Develop others – while sometimes time consuming, it’s an investment in your movement that pays huge dividends. When leaders coach, educate, enhance self-determination and otherwise share power, they demonstrate profound trust in and respect for others’ abilities

5. Encourage and Uplift

(What keeps us going?)

Activist work, particularly direct action, is difficult, isolating, stressful, and fraught with risks. It’s hard to maintain motivation, energy, and a sense of purpose. People need encouragement to function at their best and to persist. They need emotional fuel to replenish their spirits. At the same time, no one is likely to persist for very long when they feel ignored or taken for granted. Often the best, or only, way to keep comrades going is through your demonstrated appreciation, pride, and affection for them and what they’re doing. And when they experience wins small or large, these occasions should be all the more celebrated, given the challenges.

Encouraging leaders recognize contributions individuals make. They communicate that they believe in the abilities of their comrades to help them achieve their purpose. Belief in others is crucial, because positive expectations influence comrades’ efficacy and aspirations. Don’t just tell them you believe in them, either – show them by how you behave toward them. And to do this well, get close to them; be out and about or at least in regular contact.

Celebrate the values and hard-won victories, even if they are small wins. Create a sense of community: celebrations are among the most significant way people display respect and gratitude, renew a sense of community, and recall shared values & traditions. Celebrations are important ways leaders communicate what’s important to them and the organization.

Leaders can also provide social support, and champion systems that enable support for all comrades. Supportive relationships among comrades, characterized by genuine belief in and advocacy for the interests of others, are critical to maintain vitality. Social support networks are essential for sustaining motivation & work as an antidote to burnout. Keep your comrades on the road, as they say, by supporting them.

Invest in fun. In a difficult climate for activists, people need to have a sense of personal well-being (which fun can contribute to) to sustain their commitment. And leaders set the tone. Be yourself, but build fun into the work itself, celebrations, or personal / team recognition.

Leadership as a Role

It’s exceedingly difficult for resistance organizations or the movement writ large to function without a broad spectrum of individual activists taking on leadership roles. Characterizing leadership as a role is important, because such a representation emphasizes that anyone can assume leadership, depending on circumstance, task, and so on. This realization also de-emphasizes the importance of organizational position and hierarchy, to – in fact, our movement is more likely to be effective when leadership is widely dispersed. Then, we better leverage the diverse talents and experiences at our disposal. We also generate better ‘bench strength’ so when a leadership position or new role emerges, we have the capacity on board to meet that challenge.

When we accept that leadership is a role, we free ourselves from the assumption (myth) that some people are ‘gifted’ with leadership ability, while others are not. Everyone possesses leadership potential, and as resistance warriors we are behooved to develop the skills and values to sharpen our capacity to lead. In this way, ‘leadership’ is wholly consistent with our collective identity. Anyone can take on the mantle of leadership, depending on the circumstances and the makeup of the group she or he find himself or herself part of. Depending on your task-relevant skills or passion, you may be asked to take the lead. And if you’re not asked, step up anyway. We need more of you to do just that.

In case you think you can’t use these skills if you’re new to resistance/your group or not a top staff member, think again: You’re likely a member of some team, task force or committee that can benefit from leadership. You’re also part of some community that needs leadership to deepen, evolve, or thrive.

Don’t wait for an invitation to lead.

Becoming a Better Leader

Reading through this entry, and even checking out other resources, will not make you a better leader, any more than reading about becoming a better baseball hitter will get you to the major leagues. So how can you improve your leadership? Same way you get to Carnegie Hall.

We know leadership consists of observable and learnable behaviors. Even if you’re a highly experienced leader, you can improve your ability to lead if you commit to this process:

Adopt a model of leadership to aspire to, with a behavioral basis. Otherwise, you’re just guessing about what to observe and practice. You have that model – the one we introduced here.

- Observe positive models of those behaviors.

- Get feedback on your present use of the desired behaviors based on this model. This can be via written feedback, discussions with peers, or working with a mentor or coach.

- Reflect on the results.

- Set goals for yourself and/or build a development plan.

- Practice the behaviors.

- Ask for and receive updated feedback on your performance.

- Set new goals.

- Repeat.

You don’t need to take this trip alone, and in fact you’ll find it much easier with others. Consider getting a mentor or coach, or joining a leadership support group. You may have to recruit, perhaps with the promise that you are working to improve, but the results can be enriched substantially.

Final Thoughts

If your Mom was dying, you’d do anything to save her. Well, she is and you will. Resistance is risky, and direct action scary, but learning to be a better leader and maybe occasionally being uncomfortable? C’mon! You can do it.

Fred Gibson is an environmental and social justice activist. Living in Colorado off and on since 1970, he’s witnessed the native beauty and biological diversity of the Front Range, as well as its ongoing destruction. He is determined to reverse that trend. An organizational psychologist, Fred offers his experience to build effective leadership and organizational capacity to groups that resist the destruction of the planet. In addition to his DGR membership, Fred is co-founder of Communities that Protect and Resist.

Resources

Reading List

- James M. Kouzes & Barry Z. Posner: The Leadership Challenge. 2012. San Francisco: Wiley. (The basis for the practices. There’s more detail and anecdotes to flesh out the topics we discussed. You may also be able to find the text online.)

- Larraine R. Matusak: Finding Your Voice: Learning to Lead…Anywhere You Want to Make a Difference. 1997. San Francisco: Jossy-Bass. (A good ‘intro’ to leadership: accessible, non-academic, with a practical bent. Has a motivational component, and is pretty short.)

- Richard L. Hughes, Robert C. Ginnett, & Gordon J. Curphy. Leadership: Enhancing the Lessons of Experience. Boston: McGraw-Hill. (Considered by many the gold standard for teaching leadership, especially at the undergrad level. Comprehensive account of the major systems and theories of leadership and its practice. Lots of reflection questions and developmental work, too. )

Other

You can check out Communities that Protect and Resist for a conceptual model and examples of how to build an oppositional community. https://ctpr.home.blog

Contact DGR to sign up our Leadership for Resistance course.

Featured image: Kurdishstruggle, CC BY 2.0

by DGR News Service | May 18, 2020 | Movement Building & Support

Resistance movements need two things: loyalty, and material support.

— Lierre Keith

As you read this, DGR organizers in Manila, Kathmandu, Auckland, Denver, Paris—all over the world—are building a resistance movement to defend the living planet and rebuild sustainable human communities.

To do our work, we need sustainable funding. We need to sign up at least thirty more people to our monthly donor program in the next month. Can you be one of those people? If you can’t donate, no problem. Most of us are poor. But we’re working hard. This weekend, for example, our permaculture wing distributed native trees, seedlings, planter boxes, and revolutionary literature to unhoused people on the West Coast; DGR Asia Pacific held its second-ever organizing meeting; and we planned the next steps in our tactical direct action training curriculum.

If you can’t donate, no problem. Most of us are poor. But we’re working hard. This weekend, for example, our permaculture wing distributed native trees, seedlings, planter boxes, and revolutionary literature to unhoused people on the West Coast; DGR Asia Pacific held its second-ever organizing meeting; and we planned the next steps in our tactical direct action training curriculum.

All this takes money. And our radical, uncompromising stance comes at a price. Liberal foundations and big corporations won’t fund any organization that actually represents a threat to the ruling class.

Instead, we rely on small, grassroots donations – averaging less than $50 per person – and have only one paid staff. Our current funding levels aren’t sustainable in the long-term, and we need to expand our fundraising base significantly to build a stronger movement and take our revolutionary action to the next level.

Can you join us as a monthly donor? For those who are already donating: we cannot thank you enough.

For those who are already donating: we cannot thank you enough.

Sincerely,

Max Wilbert

Organizing Director

Deep Green Resistance

by DGR News Service | May 15, 2020 | Culture of Resistance, Listening to the Land

What will come after industrial capitalism? In this piece, Kara Huntermoon envisions how to begin creating ecological economies through adaptation to place.

Ecological Economies

by Kara Huntermoon

Humans are ‘culture creatures.’ That means we evolve on two levels: biological and cultural.

Biological evolution is physical adaptation to environmental stresses. All life on Earth evolves biologically. A tree growing in a cold area must adapt to the cold or die. Those individual trees in the population with sufficient capacity to tolerate the cold are the ones who reproduce, eventually leading to a population of trees genetically distinct enough from other similar trees to be called a “species.”

Cultural evolution does not require physical adaptation.

A group of humans can build houses, grow or collect foods, make clothing, create tools, and organize waste management in many different ways. These different cultural adaptations also evolve. That means that as we take in information from the environment, we change our culture to adapt to the new information.

This ability makes humans highly adaptable to very extreme differences in climate and ecology.

The Inuit have developed a sustainable culture in the far north, in a place where the sun literally does not rise for two months in the winter, temperatures fall below zero for long periods of time, and the ground never thaws out, even in summer. On the other extreme, Australian aborigines developed a sustainable culture in a place where there is very little rain, summer temperatures regularly exceed 95 degrees Fahrenheit, and soils are so low in nutrients that agriculture―even livestock grazing―cannot be sustainably practiced. The people of the Inuit nations and the people of the Aboriginal nations are not physically distinct enough from each other to be considered separate species. They did not need to speciate because their adaptations happened on a cultural level.

Humans can adapt to things that would not be found in nature.

Driving a car, flying in an airplane, watching television, and using cell phones all seem normal to us, because our cultural adaptations normalize them. When humans live separate from relationships with ecological communities, they evolve cultures that ignore ecological communities. This is what happens in cities, where entire groups of people do not have access to the plant and animal people who support human life. Water comes out of a tap, so we do not have the opportunity to watch how it flows through the rivers as we collect water to drink. Warmth comes from electric heaters, so we do not have the opportunity to collect firewood and notice the health of the forest that warms us. Our cultures evolve a kind of ignorance of life-supporting beings.

When human cultures engage in active conversation with ecological community relationships, they evolve ways to adapt to their ecosystems.

Thus a desert-dwelling people will evolve a culture of nomadic land-tending, where they travel over large distances to avoid having too big an impact on any one fragile area of the ecosystem. People who live in areas with regular summer rain are more likely to practice active agriculture. Mountain people often develop cultures of livestock tending that include moving the herds up the mountains to graze during the summer, and down into barns for protection from the winter. Any of these cultural patterns could be indefinitely sustainable, as long as they are practiced “in place,” enmeshed in their ecology of origin, where they can receive feedback from the generations-long conversations that happen between humans and their communities.

Humans need multiple smaller in-place adapted cultural groups in order to maintain diversity and resilience.

We decry the loss of genetic diversity in food crops, because when you plant only a few genetic lines, the crop becomes really susceptible to destruction. The Irish potato famine is a good example of this. Irish people had access to only a small percentage of the potato genetic diversity available, because their original potato stock was a small amount imported from South America. This small amount was propagated until it became the basis of the entire country’s agriculture. When blight infected the potatoes, all strains being grown were susceptible, and people starved. If more strains had been grown, there would have been some with resistance to blight.

Humans are the same.

When we have a world-wide monoculture, there is less resilience for our species to respond to challenges. US hegemony and colonialism, combined with genocide of native peoples worldwide, has made our species less adaptable. For example, there are many ways to manage human waste, and they are dependent on their local ecology. In some tropical areas, it makes sense to defecate in running rivers, because poisonous snakes are attracted to the insects that gather around human feces on land. Using the river to remove that risk works well as long as the human population is small enough, the river is big enough, and the animals in the river who eat the poop maintain healthy populations.

There are people living in Eugene who refuse to use a humanure sawdust bucket toilet. Their cultural expectation is such that pooping in clean drinking water and flushing it away down a pipe seems normal to them, and other options become unacceptable. For someone from a different culture, even from a different subculture of this culture, that seems strange. Why would you foul your drinking water, and create pollution by combining that slurry with millions of other flushes, and then create a sub-class of people who try to clean it with nasty chemical processes? When handled differently, that “waste” could enrich your soil and help you grow healthy crops.

The cultural aspects of humanure management are relatively easy to change. My favorite way is to use finished humanure compost in the garden while someone is helping me. People will hesitantly follow me up to the pile, and hold the wheelbarrow for me while I fork into the finished compost. Slowly their faces change as the wheelbarrow fills. It looks like finished compost, it smells like fresh soil, and they can tell that it is healthy. “Can I touch it?” asked one. “Of course. It won’t hurt you.” Soon they are raking their hands through the compost, smoothing it out on the top few inches of the garden bed.

We need to be able to experiment like this to find ways to adapt in place.

In the future, we will not be able to depend on large-scale infrastructure like flush toilets, underground sewer systems to transport the flushes, and wastewater treatment plants to process the slurry. This system also relies on electricity, regular paychecks for the workers, and fossil fuels to transport the processed slurry to its next location. There are too many opportunities for this system to break down out of our control, leaving us in the position of needing to safely manage our own feces without spreading disease. The risk of disease transmission after interruptions in waste management systems is really high, as for example in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria.

Recreating ecological economies requires us to stay in place and commit to a single territory.

We cannot begin multi-generation conversations with our ecological communities if we are constantly leaving those communities. Even the difference between the West Eugene wetlands and the South Eugene hills is significant. We must start small, in our own neighborhoods, and then create a bioregional network of knowledge-tenders who can increase understanding of the big-picture patterns of our area. Learn the names and habits of the birds, insects, and mammals in your home. Look up ethnobotany for the plants, and start to use them for medicine, food, and fiber. Rebuild a local culture of dependence on each other (both other humans and other life). Get to know your neighbors and help each other.

The ‘homelessness’ distress pattern of colonialist dominator culture has infected all of us.

What would it take for you to commit to a place? To where would you commit? What would you have to give up in order to make that commitment? How would you cope with the experiences of loss when others are unable or unwilling to make that same commitment, and you lose relationships with neighbors that you have fostered for years? Who will you teach to stay, and how will you teach it? How can you create a local economy that has more resilience than the national one, and entices people to stay in place because “moving for a job” no longer makes sense? How can you love as big as possible?

Keep asking these questions.

Journal about them, talk with others about them, notice your feelings about them. Live with the questions.

Seek answers in all aspects of your life.

Kara Huntermoon is one of seven co-owners of Heart-Culture Farm Community, near Eugene, Oregon. She spends most of her time in unpaid labor in service of community: child-raising, garden-growing, and emotion/relationship management among the community residents. She also teaches Liberation Listening, a personal growth process that focuses on ending oppression.

Featured image by Christian Ziegler, Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license.

We Need Your Help

Right now, Deep Green Resistance organizers are at work building a political resistance resistance movement to defend the living planet and rebuild just, sustainable human communities.

In Manila, Kathmandu, Auckland, Denver, Paris—all over the world—we are building resistance and working towards revolution. We need your help.

Can you become a monthly donor to help make this work possible?

Not all of us can work from the front lines, but we can all contribute. Our radical, uncompromising stance comes at a price. Foundations and corporations won’t fund us because we are too radical. We operate on a shoestring budget (all our funding comes from small, grassroots donations averaging less than $50) and have only one paid staff.

Monthly donors are the backbone of our fundraising because they provide us with reliable, steady income. This allows us to plan ahead. Becoming a monthly donor, or increasing your contribution amount, is the single most important thing we can do to boost our financial base.

Current funding levels aren’t sustainable for the long-term, even with our level of operations now. We need to expand our fundraising base significantly to build stronger resistance and grow our movement.

Click here to become a monthly donor. Thank you.