Editor’s note: Animal abuse is a foundational pillar of the modern industrial food system. We stand against factory farming, vivisection, and other forms of animal testing and abuse. As an organization, however, we do not advocate veganism—and in fact, DGR co-founder Lierre Keith wrote a book called The Vegetarian Myth arguing that vegetarianism and veganism are not a political or ecological solution. However, there are vegans and vegetarians involved in Deep Green Resistance, and we overlap on many goals. This article is the story of the A nimal Liberation Front, a movement well worth learning from.

By Chad Nelson

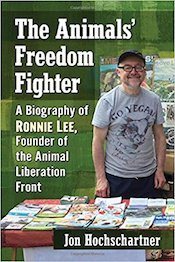

It’s about time. Someone has finally written a biography on the real father of the animal liberation movement – Ronnie Lee. Lee’s lifelong work for animals spans five decades and counting. During this time, he has been involved in just about every form of animal advocacy imaginable – direct action, grassroots vegan outreach, political campaigning, public interest campaigns, and animal fostering, to name a few. Perhaps best known for founding the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and being jailed numerous times for illegal direct actions, Ronnie Lee now focuses exclusively on above-ground animal advocacy, having retired from his earlier, extensive underground career.

Author Jon Hochshartner’s access to Lee (and some of his friends and family) provides us an intimate window into Lee’s life as a freedom fighter for animals. Lee’s childhood and early adult years are shockingly unremarkable in the sense that there is little to indicate he would go on to become a pioneer in the animal liberation movement. Although it is clear Lee grew up with a fondness for animals, an aversion to authority, and a keen sense of justice, the same can be said of many people who neither become vegan nor pursue animal liberation. What specifically led Lee to become The Animals’ Freedom Fighter, one can never know. But this unremarkable childhood makes Lee’s segue into full-fledged warrior all the more startling and exhilarating.

Lee’s come to Jesus moment seems to have instead been a confluence of events – no single one having been definitive. One early turning point appears to have been Lee’s innocuous story of how he became vegan. As a teen, Lee, by then a vegetarian, was introduced to veganism by his older sister’s boyfriend – a healthy, robust, vegan athlete. As with many vegetarians, Lee came to understand the hypocrisy of abstaining from  eating animal flesh while at the same time continuing to consume other animal byproducts. It only took a single vegan role model for Lee to connect the dots and realize veganism is not only just, but healthy too.

eating animal flesh while at the same time continuing to consume other animal byproducts. It only took a single vegan role model for Lee to connect the dots and realize veganism is not only just, but healthy too.

Lee’s subsequent entry into the world of direct action gives us an exciting new window into the early 70s-era radical animal advocacy scene in the United Kingdom. Lee’s involvement with the Hunt Saboteurs Association (HSA) began to blossom into more pointed forms of direct action as time went on. In an effort to refine the efficacy of his hunt sabbing efforts, Lee became more and more motivated to declare full scale war on all animal exploiters. While still “hunting the hunters” with the HSA, Lee felt it more impactful to engage in covert, preemptive forms of hunt sabotage, such as disabling the hunters’ automobiles and ransacking hunt lodges. Lee and some of his more daring saboteur partners eventually leveraged their hunt sab experiences, directing similar attacks against other institutional exploiters like butchers, factory farmers, and vivisectors, whose labs Lee would burn to the ground under the cover of darkness.

Lee’s shift to more aggressive tactics are praiseworthy. If the war against animal exploiters is truly that – a war – no options can be taken off the table no matter what the law has to say about them. In the war for animal liberation, there is a role for everyone to play, from the underground saboteur to the aboveground political actor. Some of these tactics may seem at odds, and activists wedded to one or another tactic may accuse the other of setting the movement back. At various times in history, certain forms of activism may prove more beneficial and strategically sound than others. But in the grand scheme of things, any action for animals is an important brick in the wall, and they will all add up to achieve total liberation for animals in the long run. Lee’s life exemplifies the value of this veritable smorgasbord of tactics.

Lee’s willingness to serve hard time for his involvement in illegal direct actions has given way to his more systemic approach. Lee now prefers to focus his efforts on vegan tabling and leafletting, and taking part in Green Party politics. Having spent a considerable amount of his life behind bars, one cannot blame Lee for the shift. Nevertheless, it is hard not to look at Lee’s hard-edged ALF years with great admiration. Hochschartner paints a picture of a tireless Robinhood-for-animals who threw caution to the wind, never missing an opportunity to put a brick through an animal exploiter’s window, rescue an animal from captivity, or burn down a torture chamber. On more than one occasion, Lee tells Hochshartner that he knew his sprees would end in jail time, but that each time he simply sought to extend them for as long as he could. One has to wonder whether animal exploitation could survive if all vegans became this courageous overnight.

Alas, Lee’s direct action did inspire many to become that courageous. As with many social movements, the actions of one or two brave souls can serve as a greenprint for others to follow. The ALF continues to thrive to this day as an anonymous, leaderless movement, as the baton gets passed from one liberationist to the next through a series of direct actions and communiques describing them. Lee’s ALF actions in the UK quickly encouraged others, uncoordinated and unbeknownst to Lee, in all corners of the globe. These actions continue to flourish today even despite a conservative political climate which punishes them increasingly harshly.

Any student of animal liberation would be well-advised to read The Animals’ Freedom Fighter in order to help them determine what role is appropriate for them. The book is a welcome addition, as both a tactical encyclopedia and an important historical account. Lee’s life as an animal advocate has been full and diverse, and one has to wonder what else Lee might have up his sleeve. Hopefully Hochshartner will have no choice but to update Lee’s biography in the coming years.

Chad Nelson is a peace advocate.

This article was originally published in Counterpunch.