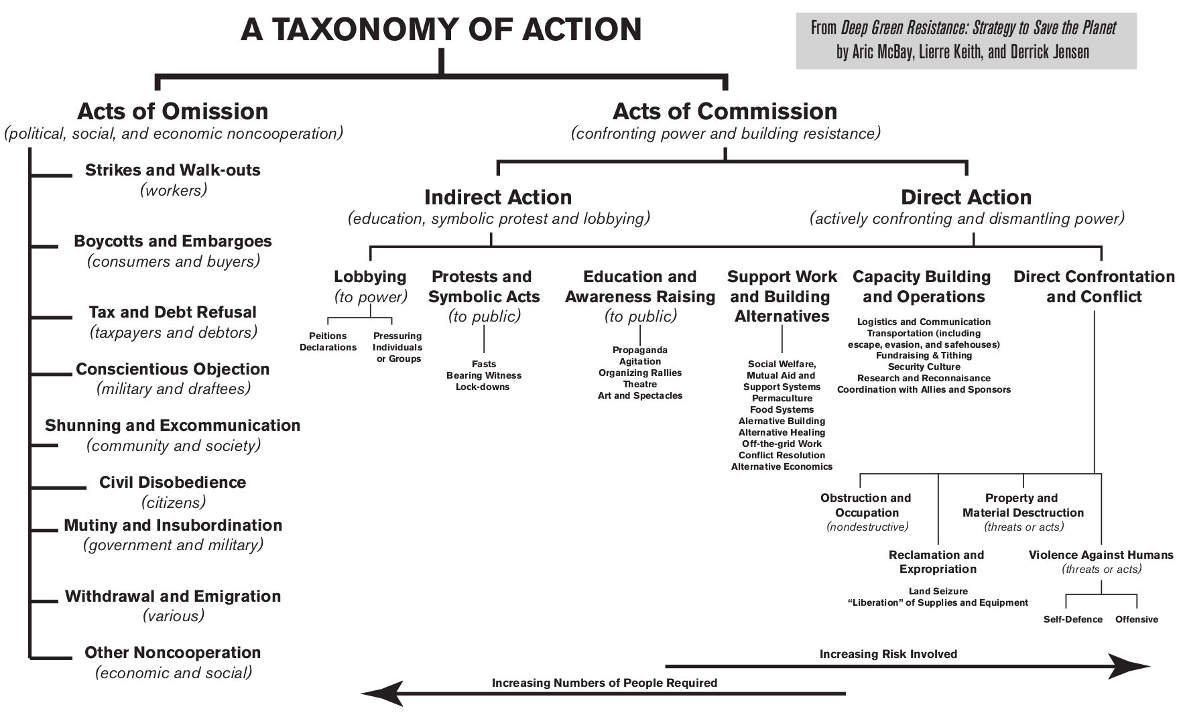

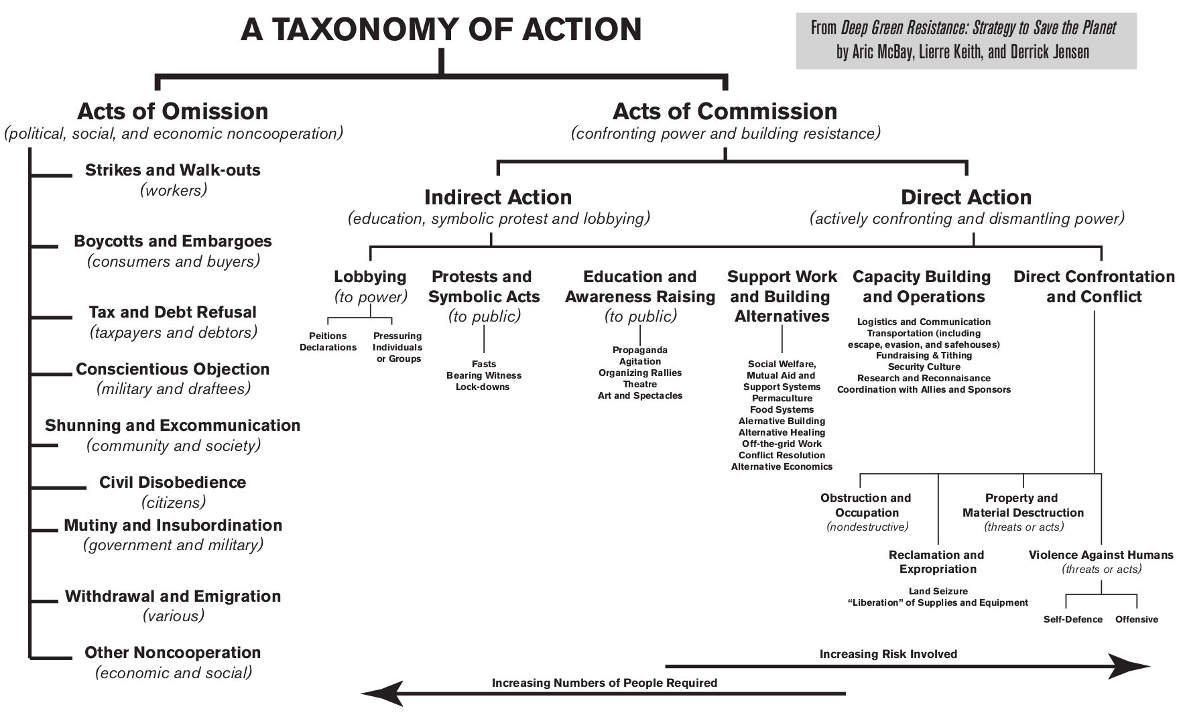

by DGR News Service | Dec 13, 2019 | Direct Action

This post is excerpted from the book, Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. Click here to buy a copy of the book or read it online. The book includes a detailed exploration of the morality of different forms of resistance, and is highly recommended reading. This is part 3 in a series. Part 1 is here, and part 2 is here.

Ultimately, success requires direct confrontation and conflict with power; you can’t win on the defensive. But direct confrontation doesn’t always mean overt confrontation. Disrupting and dismantling systems of power doesn’t require advertising who you are, when and where you are planning to act, or what means you will use.

Back in the heyday of the summit-hopping “anti-globalization” movement, I enjoyed seeing the Black Bloc in action. But I was discomfited when I saw them smash the windows of a Gap storefront, a Starbucks, or even a military recruiting office during a protest. I was not opposed to seeing those windows smashed, just surprised that those in the Black Bloc had deliberately waited until the one day their targets were surrounded by thousands of heavily armed riot police, with countless additional cameras recording their every move and dozens of police buses idling on the corner waiting to take them to jail. It seemed to be the worst possible time and place to act if their objective was to smash windows and escape to smash another day.

Of course, their real aim wasn’t to smash windows—if you wanted to destroy corporate property there are much more effective ways of doing it—but to fight. If they wanted to smash windows, they could have gone out in the middle of the night a few days before the protest and smashed every corporate franchise on the block without anyone stopping them. They wanted to fight power, and they wanted people to see them doing it. But we need to fight to win, and that means fighting smart. Sometimes that means being more covert or oblique, especially if effective resistance is going to trigger a punitive response.

That said, actions can be both effective and draw attention. Anarchist theorist and Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin argued that “we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda.” The intent of the deed is not to commit a symbolic act to get attention, but to carry out a genuinely meaningful action that will serve as an example to others.

Four Methods of Direct Confrontation

There are four basic ways to directly confront those in power. Three deal with land, property, or infrastructure, and one deals specifically with human beings. They include:

- Obstruction and occupation;

- Reclamation and expropriation;

- Property and material destruction (threats or acts); and

- Violence against humans (threats or acts)

In other words, in a physical confrontation, the resistance has three main options for any (nonhuman) target: block it, take it, or break it.

Nondestructive Obstruction or Occupation

Let’s start with nondestructive obstruction or occupation—block it. This includes the blockade of a highway, a tree sit, a lockdown, or the occupation of a building. These acts prevent those in power from using or physically destroying the places in question. Provided you have enough dedicated people, these actions can be very effective.

But there are challenges. Any prolonged obstruction or occupation requires the same larger support structure as any direct action. If the target is important to those in power, they will retaliate. The more important the site, the stronger the response. In order to maintain the occupation, activists must be willing to fight off that response or suffer the consequences.

An example worth studying for many reasons is the Oka crisis of 1990. Mohawk land, including a burial ground, was taken by the town of Oka, Quebec, for—get ready—a golf course. The only deeper insult would have been a garbage dump. After months of legal protests and negotiations, the Mohawk barricaded the roads to keep the land from being destroyed. This defense of their land (“We are the pines,” one defender said) triggered a full-scale military response by the Canadian government. It also inspired acts of solidarity by other First Nations people, including a blockade of the Mercier Bridge. The bridge connects the Island of Montreal with the southern suburbs of the city—and it also runs through the Mohawk territory of Kahnawake. This was a fantastic use of a strategic resource. Enormous lines of traffic backed up, affecting the entire area for days.

At Kanehsatake, the Mohawk town near Oka, the standoff lasted a total of seventy-eight days. The police gave way to RCMP, who were then replaced by the army, complete with tanks, aircraft, and serious weapons. Every road into Oka was turned into a checkpoint. Within two weeks, there were food shortages.

Until your resistance group has participated in a siege or occupation, you may not appreciate that on top of strategy, training, and stalwart courage—a courage that the Mohawk have displayed for hundreds of years—you need basic supplies and a plan for getting more. If an army marches on its stomach, an occupation lasts as long as its stores. Getting food and supplies into Kanehsatake and then to the people behind the barricades was a constant struggle for the support workers, and gave the police and army plenty of opportunity to harass and humiliate resisters. With the whole world watching, the government couldn’t starve the Mohawk outright, but few indigenous groups engaged in land struggles are lucky enough to garner that level of media interest. Food wasn’t hard to collect: the Quebec Native Women’s Association started a food depot and donations poured in. But the supplies had to be arduously hauled through the woods to circumvent the checkpoints. Trucks of food were kept waiting for hours only to be turned away.31 Women were subjected to strip searches by male soldiers. At least one Mohawk man had a burning cigarette put out on his stomach, then dropped down the front of his pants.32 Human rights observers were harassed by both the police and by angry white mobs.33

The overwhelming threat of force eventually got the blockade on the bridge removed. At Kanehsatake, the army pushed the defenders to one building. Inside, thirteen men, sixteen women, and six children tried to withstand the weight of the Canadian military. No amount of spiritual strength or committed courage could have prevailed.

The siege ended when the defenders decided to disengage. In their history of the crisis, People of the Pines, Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera write, “Their negotiating prospects were bleak, they were isolated and powerless, and their living conditions were increasingly stressful . . . tempers were flaring and arguments were breaking out. The psychological warfare and the constant noise of military helicopters had worn down their resistance.”34 Without the presence of the media, they could have been raped, hacked to pieces, gunned down, or incinerated to ash, things that routinely happen to indigenous people who fight back. The film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance documents how viciously they were treated when the military found the retreating group on the road.

One reason small guerilla groups are so effective against larger and better-equipped armies is because they can use their secrecy and mobility to choose when, where, and under what circumstances they fight their enemy. They only engage in it when they reasonably expect to win, and avoid combat the rest of the time. But by engaging in the tactic of obstruction or occupation a resistance group gives up mobility, allowing the enemy to attack when it is favorable to them and giving up the very thing that makes small guerilla groups so effective.

The people at Kanehsatake had no choice but to give up that mobility. They had to defend their land which was under imminent threat. The end was written into the beginning; even 1,000 well-armed warriors could not have held off the Canadian armed forces. The Mohawk should not have been in a position where they had no choice, and the blame here belongs to the white people who claim to be their allies. Why does the defense of the land always fall to the indigenous people? Why do we, with our privileges and resources, leave the dirty and dangerous work of real resistance to the poor and embattled? Some white people did step up, from international observers to local church folks. But the support needs to be overwhelming and it needs to come before a doomed battle is the only option. A Mohawk burial ground should never have been threatened with a golf course. Enough white people standing behind the legal efforts would have stopped this before it escalated into razor wire and strip searches. Oka was ultimately a failure of systematic solidarity.

Reclamation and Expropriation

The second means of direct conflict is reclamation and expropriation—take it. Instead of blocking the use of land or property, the resistance takes it for their own use. For example, the Landless Workers Movement—centered in Brazil, a country renowned for unjust land distribution—occupies “underused” rural farmland (typically owned by wealthy absentee landlords) and sets up farming villages for landless or displaced people. Thanks to a land reform clause in the Brazilian constitution, the occupiers have been able to compel the government to expropriate the land and give them title. The movement has also engaged in direct action like blockades, and has set up its own education and literacy programs, as well as sustainable agriculture initiatives. The Landless Workers Movement is considered the largest social movement in Latin America, with an estimated 1.5 million members.

Expropriation has been a common tactic in various stages of revolution. “Loot the looters!” proclaimed the Bolsheviks during Russia’s October Revolution. Early on, the Bolsheviks staged bank robberies to acquire funds for their cause. Successful revolutionaries, as well as mainstream leftists, have also engaged in more “legitimate” activities, but these are no less likely to trigger reprisals. When the democratically elected government of Iran nationalized an oil company in 1953, the CIA responded by staging a coup. And, of course, guerilla movements commonly “liberate” equipment from occupiers in order to carry out their own activities.

Property and Material Destruction

The third means of direct conflict is property and material destruction—break it. This category includes sabotage. Some say the word sabotage comes from early Luddites tossing wooden shoes (sabots) into machinery, stopping the gears. But the term probably comes from a 1910 French railway strike, when workers destroyed the wooden shoes holding the rails—a good example of moving up the infrastructure. And sabotage can be more than just physical damage to machines; labor activism has long included work slowdowns and deliberate bungling.

Sabotage is an essential part of war and resistance to occupation. This is widely recognized by armed forces, and the US military has published a number of manuals and pamphlets on sabotage for use by occupied people. The Simple Sabotage Field Manual published by the Office of Strategic Services during World War II offers suggestions on how to deploy and motivate saboteurs, and specific means that can be used. “Simple sabotage is more than malicious mischief,” it warns, “and it should always consist of acts whose results will be detrimental to the materials and manpower of the enemy.” It warns that a saboteur should never attack targets beyond his or her capacity, and should try to damage materials in use, or destined for use, by the enemy. “It will be safe for him to assume that almost any product of heavy industry is destined for enemy use, and that the most efficient fuels and lubricants also are destined for enemy use.” It encourages the saboteur to target transportation and communications systems and devices in particular, as well as other critical materials for the functioning of those systems and of the broader occupational apparatus. Its particular instructions range from burning enemy infrastructure to blocking toilets and jamming locks, from working slowly or inefficiently in factories to damaging work tools through deliberate negligence, from spreading false rumors or misleading information to the occupiers to engaging in long and inefficient workplace meetings.

Ever since the industrial revolution, targeting infrastructure has been a highly effective means of engaging in conflict. It may be surprising to some that the end of the American Civil War was brought about in large part by attacks on infrastructure. From its onset in 1861, the Civil War was extremely bloody, killing more American combatants than all other wars before or since, combined. After several years of this, President Lincoln and his chief generals agreed to move from a “limited war” to a “total war” in an attempt to decisively end the war and bring about victory.

Historian Bruce Catton described the 1864 shift, when Union general “[William Tecumseh] Sherman led his army deep into the Confederate heartland of Georgia and South Carolina, destroying their economic infrastructures.” Catton writes that “it was also the nineteenth-century equivalent of the modern bombing raid, a blow at the civilian underpinning of the military machine. Bridges, railroads, machine shops, warehouses—anything of this nature that lay in Sherman’s path was burned or dismantled.” Telegraph lines were targeted as well, but so was the agricultural base. The Union Army selectively burned barns, mills, and cotton gins, and occasionally burned crops or captured livestock. This was partly an attack on agriculture-based slavery, and partly a way of provisioning the Union Army while undermining the Confederates. These attacks did take place with a specific code of conduct, and General Sherman ordered his men to distinguish “between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor or industrious, usually neutral or friendly.”

Catton argues that military engagements were “incidental” to the overall goal of striking the infrastructure, a goal which was successfully carried out. As historian David J. Eicher wrote, “Sherman had accomplished an amazing task. He had defied military principles by operating deep within enemy territory and without lines of supply or communication. He destroyed much of the South’s potential and psychology to wage war.” The strategy was crucial to the northern victory.

Violence Against Humans

The fourth and final means of direct conflict is violence against humans. Here we’re using violence specifically and explicitly to mean harm or injury to living creatures. Smashing a window, of course, is not violence; violence does include psychological harm or injury. The vast majority of resistance movements know the importance of violence in self-defense. Malcolm X was typically direct: “We are nonviolent with people who are nonviolent with us.”

In resistance movements, offensive violence is rare—virtually all violence used by historical resistance groups, from revolting slaves to escaping concentration camp prisoners to women shooting abusive partners, is a response to greater violence from power, and so is both justifiable and defensive. When prisoners in the Sobibór extermination camp quietly SS killed guards in the hours leading up to their planned escape, some might argue that they committed acts of offensive violence. But they were only responding to much more extensive violence already committed by the Nazis, and were acting to avert worse violence in the immediate future.

There have been groups which engaged in systematic offensive violence and attacks directed at people rather than infrastructure. The Red Army Faction (RAF) was a militant leftist group operating in West Germany, mostly in the 1970s and 1980s. They carried out a campaign of bombings and assassination attempts mostly aimed at police, soldiers, and high-ranking government or business officials. Another example would be the Palestinian group Hamas, which has carried out a large number of violent attacks on both civilians and military personnel in Israel. (It is also a political party and holds a legally elected majority in the Palestinian National Authority. It’s often ignored that much of Hamas’s popularity comes from its many social programs, which long predate its election to government. About 90 percent of Hamas’s activities are these social programs, which include medical clinics, soup kitchens, schools and literacy programs, and orphanages.)

It’s sometimes argued that the use of violence is never justifiable strategically, because the state will always have the larger ability to escalate beyond the resistance in a cycle of violence. In a narrow sense that’s true, but in a wider sense it’s misleading. Successful resistance groups almost never attempt to engage in overt armed conflict with those in power (except in late-stage revolutions, when the state has weakened and revolutionary forces are large and well-equipped). Guerilla groups focus on attacking where they are strongest, and those in power are weakest. The mobile, covert, hit-and-run nature of their strategy means that they can cause extensive disruption while (hopefully) avoiding government reprisals.

Furthermore, the state’s violent response isn’t just due to the use of violence by the resistance, it’s a response to the effectiveness of the resistance. We’ve seen that again and again, even where acts of omission have been the primary tactics. Those in power will use force and violence to put down any major threat to their power, regardless of the particular tactics used. So trying to avoid a violent state response is hardly a universal argument against the use of defensive violence by a resistance group.

The purpose of violent resistance isn’t simply to do violence or exact revenge, as some dogmatic critics of violence seem to believe. The purpose is to reduce the capacity of those in power to do further violence. The US guerilla warfare manual explicitly states that a “guerrilla’s objective is to diminish the enemy’s military potential.” (Remember what historian Bruce Catton wrote about the Union Army’s engagements with Confederate soldiers being incidental to their attacks on infrastructure.) To attack those in power without a strategy, simply to inflict indiscriminate damage, would be foolish.

The RAF used offensive violence, but probably not in a way that decreased the capacity of those in power to do violence. Starting in 1971, they shot two police and killed one. They bombed a US barracks, killing one and wounding thirteen. They bombed a police station, wounding five officers. They bombed the car of a judge. They bombed a newspaper headquarters. They bombed an officers’ club, killing three and injuring five. They attacked the West German embassy, killing two and losing two RAF members. They undertook a failed attack against an army base (which held nuclear weapons) and lost several RAF members. They assassinated the federal prosecutor general and the director of a bank in an attempted kidnapping. They hijacked an airliner, and three hijackers were killed. They kidnapped the chairman of a German industry organization (who was also a former SS officer), killing three police and a driver in the attack. When the government refused to give in to their demands to release imprisoned RAF members, they killed the chairman. They shot a policeman in a bar. They attempted to assassinate the head of NATO, blew up a car bomb in an air base parking lot, attempted to assassinate an army commander, attempted to bomb a NATO officer school, and blew up another car bomb in another air base parking lot. They separately assassinated a corporate manager and the head of an East German state trust agency. And as their final militant act, in 1993 they blew up the construction site of a new prison, causing more than one hundred million Deutsche Marks of damage. Throughout this period, they killed a number of secondary targets such as chauffeurs and bodyguards.

Setting aside for the time being the ethical questions of using offensive violence, and the strategic implications of giving up the moral high ground, how many of these acts seem like effective ways to reduce the state’s capacity for violence? In an industrial civilization, most of those in government and business are essentially interchangeable functionaries, people who perform a certain task, who can easily be replaced by another. Sure, there are unique individuals who are especially important driving forces—people like Hitler—but even if you believe Carlyle’s Great Man theory, you have to admit that most individual police, business managers, and so on will be quickly and easily replaced in their respective organizations. How many police and corporate functionaries are there in one country? Conversely, how many primary oil pipelines and electrical transmission lines are there? Which are most heavily guarded and surveilled, bank directors or remote electrical lines? Which will be replaced sooner, bureaucratic functionaries or bus-sized electrical components? And which attack has the greatest “return on investment?” In other words, which offers the most leverage for impact in exchange for the risk undertaken?

As we’ve said many times, the incredible level of day-to-day violence inflicted by this culture on human beings and on the natural world means that to refrain from fighting back will not prevent violence. It simply means that those in power will direct their violence at different people and over a much longer period of time. The question, as ever, is which particular strategy—violent or not—will actually work.

by DGR News Service | Dec 3, 2019 | Defensive Violence, Direct Action

Photo credit: Kinessa Johnson and True Activist

Editor’s Note: DGR does not endorse Kinessa Johnson or VETPAW, and views significant parts of their work as problematic (e.g. pervasive use of nationalistic propaganda, an implicit white saviour narrative, and echoes of imperialism). However, this phenomenon is interesting and worth discussing.

by Liam Campbell

Kinessa Johnson is a heavily tattooed U.S. military veteran, she is also an experienced firearms instructor and mechanic. After completing one tour in Afghanistan she joined VETPAW, an NGO that focuses on providing training and resources for park rangers and anti-poaching groups that protect endangered species. According to Johnson, park rangers in Africa face extreme danger “they lost about 187 guys last year over trying to save rhinos and elephants.” VETPAW’s response is to send U.S. combat veterans to provide specialist training, in hopes that they can help park rangers reduce both poaching and their own casualties.

Framing their mission.

According to Johnson “after the first obvious priority of enforcing existing poaching laws, educating the locals on protecting their country’s natural resources is most important overall.” Although this perspective has an implicitly patronising tone, there is also some validity in it — park rangers are often under resourced, which results in poor training and inadequate equipment. Sending rangers highly-trained specialists makes sense, as does sending them better equipment. What gives me pause about a group like VETPAW is how they’ve framed their mission:

“VETPAW is a group of post 9/11 US veterans with combat skills who are committed to protecting and training Park Rangers to combat poaching on the ground in Africa.

We employ veterans to help fight the increasing unemployment rate of this group in the US but also, and most importantly, because their skills learned on the frontlines in Afghanistan is unrivaled. These highly trained service men and women lead the war against brutality and oppression, for both human beings and the animal kingdom.”

Problematic language.

What stands out to me is the combination of nationalistic buzzwords and the patronising framing. Why specify “post 9/11 US veterans?” Because those are all trigger words for American nationalism. It’s also problematic that their mission frames U.S. veterans as champions who opposed “brutality and oppression.” Last, but not least, is their use of the phrase “animal kingdom” which is a subconscious frame implying an inherent hierarchy (where, presumably, either humans or a christian god presides at the top).

Ecofascism.

To me, this phenomenon is reminiscent of proto ecofascism, the first seed of a new form of fascist movement that wraps itself in nationalistic flags and hides behind the morality of environmentalism. It’s also concerning that groups like VETPAW would have an obvious appeal to combat veterans who are interested in hunting economically desperate Africans, under the guise of charity.

Deep Green Perspective.

From the a Deep Green Resistance analysis perspective, this is a complex issue. It would obviously be better to quietly and respectfully provide resources to indigenously-led groups but, on the other hand, if organisations like this end up resulting in tangible reductions in poaching, that may be better than nothing. What do you think about this issue?

Let us know in the comments.

Join the Resistance

Deep Green Resistance is a political movement for liberation and revolution. We aim for nothing less than total liberation from extractive economics, white supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism, industrialism, and the culture of empire that we call civilization. This is a war for survival, and we’re losing. We aim to turn the tide. We mean to win.