by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 15, 2015 | Listening to the Land, Lobbying

By Center for Biological Diversity

After pressure from the Center for Biological Diversity and allies, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced Wednesday it will release about 10 Mexican gray wolves into the wilds of southwestern New Mexico–a move scientists say is crucial to reduce dangerous inbreeding of the rare creatures.

Just days earlier, the Center and allies sent a letter to Interior Secretary Sally Jewell, signed by 43 groups and scientists, asking her to release at least five packs of endangered Mexican gray wolves into New Mexico’s 3.3-million-acre Gila National Forest.

Back in 1998, after a Center lawsuit, the Service began reintroducing Mexican gray wolves from captive-breeding facilities into their historic U.S. Southwest range, where they had been obliterated by federal poisoning and trapping. But the Service only released wolves into a small part of Arizona’s Apache National Forest, which quickly filled with wolf families.

“Releasing Mexican wolves to the wild is the only way to save these animals from extinction,” the Center’s Michael Robinson told the Santa Fe New Mexican. “It’s vital now that enough wolves get released to diversify their gene pool and ensure they don’t waste away from inbreeding.”

Read more in the Center for Biological Diversity press release and the Santa Fe New Mexican.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 12, 2015 | Strategy & Analysis

Book Review of Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet

By Zoe Blunt

I first heard about Deep Green Resistance in the middle of a grassroots fight to stop a huge vacation-home subdivision at a wilderness park on Vancouver Island. Back then, it hadn’t really occurred to me that a book on environmental strategy was needed. Now I can tell you, it’s urgent.

Deep Green Resistance (DGR) made me a better strategist. If you’re an activist, then this book is for you. But be warned: at 520 pages (plus endnotes), it’s not light reading. Quite the opposite — DGR dares environmental groups to focus on decisive tactics rather than mindless lobbying and silly stunts.

“This book is about fighting back. And this book is about winning,” author Derrick Jensen declares in the preface to this three-way collaboration with Lierre Keith and Aric McBay.

Keith, author of The Vegetarian Myth, opens the discussion with an analysis of why “traditional” environmental action is self-defeating. For those who’ve read Jensen’s Endgame, or who have experienced the frustration of born-to-lose activism, Keith’s analysis hits the nerve.

The DGR philosophy was born from failure. In a recent interview, Jensen recounts a 2007 conversation with fellow activists who asked, “Why is it that we’re doing so much activism, and the world is being killed at an increasing rate?” “This suggests our work is a failure,” Jensen concludes. “The only measure of success is the health of the planet.”

If we keep to this course, as Keith points out, the outcome is extinction: the death of species, of people, and the planet itself. Environmental “solutions” are by now predictable, and totally out of scale with the threat we’re facing. Cloth bags, eco-branded travel mugs, hemp shirts, and recycled flip-flops won’t change the world. Wishful thinking aside, they can’t, because they don’t challenge the industrial machine. It just keeps grinding out tons of waste for every human on the earth, whether they are vegan hempsters who eat local or not. So these “solutions” amount to fiddling while the world burns.

Aric McBay, organic farmer and co-author of What We Leave Behind, says Deep Green Resistance “is about making the environmental movement effective.”

“Up to this point, you know, environmental movements have relied mostly on things like petitions, lobbying, and letter-writing,” McBay says. “That hasn’t worked. That hasn’t stopped the destruction of the planet, that hasn’t stopped the destruction of our future. So the point is if we want to be effective, we have to look at what other social movements, what other resistance movements have done in the past.”

Keith notes that a given tactic can be reformist or radical, depending on how it’s used. For example, we don’t often think of legal strategies as radical, but if it’s a mass campaign with an “or else” component that empowers people and brings a decisive outcome, then it creates fundamental change.

“Don’t be afraid to be radical,” Keith advises in a recent interview. “It’s emotional, yes; this is difficult for people, but we are going to have to name these power structures and fight them. The first step is naming them, then we’ve got to figure out what their weak points are, and then organize where they are weak and we are strong.”

Powerful words. But by then I was desperate for a blueprint, a guidebook, some signposts to help break the deadlock in our campaign to save the park. Two hundred pages into DGR, we get down to brass tacks, and find out what strategic resistance looks like.

I don’t know what I was expecting, but it wasn’t a guerrilla uprising.

To be clear, Deep Green Resistance is an aboveground, nonviolent movement, but with a twist: it calls for the creation of an underground, militant movement. The gift of this book is the revelation that strategies used by successful insurgencies can be used just as successfully by nonviolent campaigns.

McBay argues convincingly that it’s the combination of peaceful and militant action that wins. He emphasizes that people must choose between aboveground tactics and underground tactics, because trying to do both at once will get you caught.

“The cases of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X exemplify how a strong militant faction can enhance the effectiveness of less militant tactics,” McBay writes. “Some presume that Malcolm X’s ‘anger’ was ineffective compared to King’s more ‘reasonable’ and conciliatory position. That couldn’t be further from the truth. It was Malxolm X who made King’s demands seem eminently reasonable, by pushing the boundaries of what the status quo would consider extreme.”

What McBay calls “decisive ecological warfare” starts with guerrilla movements and the Art of War. Guerrilla fighting is all about asymmetric warfare. One side is well-armed, well-funded, and highly disciplined, and the other side is a much smaller group of irregulars. And yet sometimes the underdog wins. It’s not by accident, and it’s not because they are all nonviolent and pure of heart, but because they use their strengths effectively. They hit where it counts. The rebels win the hearts and minds and, crucially, the hands-on support of the civilian populace. That’s what turns the tide.

McBay notes, for example, that land reclamation has proven to be a decisive strategy. He argues that “aboveground organizers [should] learn from groups like the Landless Workers’ Movement in Latin America.” This ongoing movement “has been highly successful at reclaiming ‘underutilized’ land, and political and legal frameworks in Brazil enable their strategy,” McBay adds.

Imagine two million people occupying the Tar Sands. Imagine blocking or disrupting crucial supply lines. Imagine profits nose-diving, investors bailing out, brokers panic-selling, and the whole top-heavy edifice crashing to a halt.

The Landless Workers’ Movement operates openly. Another group, the Underground Railroad, was completely secret. Members risked their lives to help slaves escape to Canada. A similar network could help future resisters flee state persecution. Those underground networks need to form now, McBay says, before the aboveground resistance gets serious, and before the inevitable crackdown comes.

DGR categorizes effective actions as either shaping, sustaining, or decisive. If a given tactic doesn’t fit one of those categories, it is not effective, McBay says. He emphasizes, however, that all good strategies must be adaptable.

To paraphrase a few nuggets of wisdom:

Stay mobile.

Get there first with the most.

Select targets carefully.

Strike and get away.

Use multiple attacks.

Don’t get pinned down.

Keep plans simple.

Seize opportunities.

Play your strengths to their weakness.

Set reachable goals.

Follow through.

Protect each other.

And never give up.

Guerrilla warfare is not a metaphor for what’s happening to the planet. The forests, the oceans, and the rivers are victims of bloody battles that start fresh every day. Here in North America, it’s low-intensity conflict. Tactics to keep the populace in line are usually limited to threats, intimidation, arrests, and so on.

But the “war in the woods” gets real here, too. I’ve been shot at by loggers. In 1999, they burned our forest camp to the ground and put three people in the hospital. In 2008, two dozen of us faced a hundred coked-up construction workers bent on beating our asses.

Elsewhere, it’s a shooting war. Canadian mining companies kill people as well as ecosystems. We are responsible for stopping them. We know what’s happening. Failing to take effective action is criminal collusion.

Wherever we are, whatever we do, they’re murdering us. They’re poisoning us. Enbridge, Deepwater Horizon, Exxon, Shell, Suncor and all their corporate buddies are poisoning the air, the water, and the land. We know it and they know it. Animals are dying and disappearing. There will be no end to the destruction as long as there is profit in it.

This work is scary as hell. That’s why we need to be really brave, really smart and really strategic.

We have strengths our opponents will never match. We’re smarter and more flexible than they are, and we’re compelled by an overwhelming motivation: to save the planet. We’re fighting for our survival and the survival of everyone we love. They just want more money, and the only power they know is force.

As Jensen says, ask a ten-year-old what we should do to stop environmental disasters that are caused in large part by the use of fossil fuels, and you’ll get a straightforward answer: stop using fossil fuels. But what if the companies don’t want to stop? Then make them stop.

Ask a North American climate-justice campaigner, and you’re likely to hear about media stunts, Facebook apps, or people stripping and smearing each other with molasses. Not to diss hard-working activists, but unless they are building strength and unity on the ground, these tactics won’t work. They’re not decisive. They’re just silly.

Of course, if the media stunts are the lead-in to mass, no-compromise, nonviolent action to shut down polluters, I’ll see you there. I’ll even do a striptease to celebrate.

© 2012 Zoe Blunt

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 11, 2015 | Climate Change, Lobbying, Protests & Symbolic Acts, Women & Radical Feminism

SAN FRANCISCO– On Tuesday, September 29th, 2015 women from fifty countries around the world took action for climate justice, gender equality, bold climate policies and transformative solutions as part of the Global Women’s Climate Justice Day of Action organized by the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN International).

From Sudan to the Philippines, from Ecuador to France, women raised their voices collectively to show resistance to social and environmental injustice and to present their solutions and demands for a healthy, livable planet.

In Port Harcourt, Nigeria women organized the ‘African Women Uniting for Energy, Food, & Climate Justice Exchange’, during which they shared struggles and solutions around oil extraction in the Niger delta and led a march through the city. In Swaziland, women united to sign the Women’s Climate Declaration and dialogue about why women experience disproportionate climate impacts and what can be done to address this injustice.

In Scotland, women collected trash from the beach and ocean to create an art installation highlighting the plight of threatened Arctic ecosystems. In Odisha, India, women united to speak out against deforestation fueled by the mining industry, taking direct action by planting trees and writing a memorandum to local government officials calling for communitywide reforestation programs led by women. Many worldwide participants voiced their demands for their governments to keep fossil fuels in the ground and immediately finance a just transition to 100% renewable energy.

Action recaps, photos, and statements from worldwide participants have been compiled on a central Day of Action gallery, from which they are being shared and amplified across the globe.

While women held decentralized actions in their communities, WECAN International convened a September 29th hub event, ‘Women Speak: Climate Justice on the Road to Paris & Beyond’ at the United Nations Church Center in New York City, directly across the street from where world leaders gathered for the annual United Nations General Assembly.

The event featured presentations and declarations of action by outstanding leaders including Indigenous activist and Greenpeace Canada campaigner Melina Laboucan-Massismo, May Boeve of 350.org, Jacqui Patterson of the NAACP, Patricia Gualinga, Kichwa leader of Sarayaku Ecuador, Thilmeeza Hussein of Voice of Women Maldives, and a special video message from Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland and President of the Mary Robinson Foundation-Climate Justice. The event concluded with a historic announcement and presentation of the ‘Indigenous Women of the North and South – Defend Mother Earth Treaty Compact 2015’.

As the day drew to a close, WECAN International and allies united for a direct action outside of the United Nations Headquarters.

“Women around the world are well aware that what is happening in the ‘halls of power’ is not nearly enough given the degree of climate crisis that we face and the injustices and impacts felt by women on the frontlines across the globe,” explained Osprey Orielle Lake, Founder and Executive Director of the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network, “On September 29th, women across the world mobilized for bold, transformative climate change solutions and demonstrated the strength, diversity, and vitality of the women’s movement for climate justice. Women have always been on the frontlines of climate change, and now we are taking action to make sure that our voices and decision-making power are at the forefront as well. The stories, struggles, and solutions shared as part of the Global Women’s Climate Justice Day of Action will be carried forward to COP21 in Paris and beyond.”

***

The Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN International) is a solutions-based, multi-faceted effort established to engage women worldwide as powerful stakeholders in climate change, climate justice, and sustainability solutions. Recent work includes the 2013 International Women’s Earth and Climate Summit, Women’s Climate Declaration, and WECAN Women’s Climate Action Agenda. International climate advocacy is complemented with on-the-ground programs such as the Women’s for Forests and Fossil Fuel/Mining/Mega Dam Resistance, US Women’s Climate Justice Initiative, and Regional Climate Solutions Trainings in the Middle East North Africa region, Latin America, and Democratic Republic of Congo. WECAN International was founded in 2013 as a project of the 501(c)3Women’s Earth and Climate Caucus (WECC) organization and its partner eraGlobal Alliance.

www.wecaninternational.org

@WECAN_INTL

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 9, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling

By Hannibal Rhoades / Intercontinental Cry

After five years of legal contests and uncertainty, the Colombian Constitutional Court has confirmed that Yaigojé Apaporis, an indigenous resguardo (a legally recognized, collectively owned territory), also has legitimate status as a national park.

The decision is cause for celebration for Indigenous Peoples who call the region home. But it is less welcome news for Canadian multinational mining corporation Cosigo Resources, the company contesting the area’s national park status. The court’s ruling immediately and indefinitely suspends all mining activities in the park, including Cosigo’s license to mine gold from one of Yaigojé’s most sacred areas.

In the broader context of Colombia’s push to expand mining activities in the name of development, the court’s decision is seen as a significant precedent.

Since the 1980s, Colombia has protected more than 24 million hectares of the Amazon, placing an area the size of Britain back in the hands of its traditional owners. By choosing the rights of Indigenous Peoples and a new national park over multinational mining interests, the court’s decision safeguards Colombia’s achievements rather than undermining them.

THE BATTLE FOR YUISI’S GOLDEN LENS

Straddling Amazonas and Vaupés states, comprising a million hectares of the Northwestern Colombian Amazon, the pristine forest region of Yaigojé Apaporis is rich in both biological and cultural diversity.

The area hosts endangered mammals such as the giant anteater, jaguar, manatee and pink river dolphin. It is also home to the Makuna, Tanimuka, Letuama, Barasano, Cabiyari, Yahuna and Yujup-Maku Indigenous Peoples, who share a common cosmological system and rich shamanistic traditions. Together these populations act as Yaigojé’s guardians, a role that was strengthened in 1988 when, with the assistance of Colombian NGO Gaia Amazonas, they successfully established the Yaigojé Apaporis resguardo over their traditional territory. But this status has recently been tested.

Under Colombian law, a resguardo recognition grants its inhabitants collective ownership of and rights to the soil, but the subsoil remains in the control of the state and vulnerable to prospecting. With companies seeking to exploit this loophole, the Colombian Amazon has seen a tidal wave of mining interest since the mid-2000s, with the government declaring mining an “engine for development.”

Riding at the crest of this wave, in the late 2000s Canadian mining multinational Cosigo Resources made clear to local communities in Yaigojé its intention to mine for gold at a site within the resguardo known as La Libertad or Yuisi.

Local indigenous leaders say Cosigo became known to them when company representatives visited their malocas (traditional riverside houses). The indigenous leaders allege that officials offered them money in return for assurance of support the company to mine in Yuisi. These offers were rejected.

At Yuisi, a wide stretch of the Apaporis river cascades over rocks, forming roaring rapids. To the people of Yaigojé it is a vital sacred site, inextricably tied to their story of origin, identity and ability to care for the territory and the planet as a whole. Elders say “Yuisi is the crib of our way of thinking, of life and power. Everything is born here in thought: nature, the crops, trees, fruits, everything that exists, exists before in thought.”

Local shaman describe the gold and other minerals that form the bedrock of their territory as ‘lenses’ that allow them to see into the Earth, divine or diagnose any problems and correct them through rituals, prayer and thought. If gold were to be removed from Yuisi, they would lose their ability to cure and manage their territory as they have done for millennia. This is because an integral part of the territory itself would be lost. The notion that territory stops at the soil “as deep as the manioc’s root” is alien.

With negotiation with Cosigo out of the question, the traditional authorities in Yaigojé called an urgent congress of the Asociación de Capitanes Indígenas del Yaigojé Apaporis (ACIYA), an indigenous organization formed of groups living along the Apaporis River, in the area of Yaigojé that lies in Amazonas State. Having discussed the dangers posed by Cosigo’s presence and plans, ACIYA agreed that they must seek help from outside sources to further protect their territory.

“The best way to shield the territory was to call upon the state. In other words: Western disease is cured by Western medicine. If all mining licenses are given by the state, it is necessary to call on the state to defend the territory,” says Gerardo Macuna, a representative of ACIYA.

Advised that achieving national park status would extend protection to the subsoil, ACIYA and its supporters formally requested that the Colombian Government create a national park over their resguardo and traditional territory.

The people’s effort to add a third layer of protection for their territory was successful. In October 2009, Yaigojé Apaporis became Colombia’s 55th national protected area, but celebrations were short lived. Just two days after the area was awarded national park status, Cosigo Resources was granted a mining title for the Yuisi area, catalysing an epic struggle between Colombia’s will to protect the Amazon, with the help of indigenous inhabitants, or exploit it at their expense by prioritizing mining.

DEEP IN THE AMAZON, A SMOKING GUN

Despite having been granted a license, Yaigojé’s new status as a national park remained an obstacle to Cosigo. The national park status, and its accompanying legal protections for the subsoil, would need to be revoked before mining could begin.

Facing stiff opposition from both ACIYA and the Colombian National Parks authorities just as Cosigo appeared to be fighting an uphill battle, the company got what seemed an almost impossible stroke of luck. A few months after Yaigojé was declared a national park, members of indigenous organization ACITAVA from the region of Yaigojé lying in Vaupés State launched a legal challenge to Yaigojé’s status at the Colombian Constitutional Court. Led by a local settler named Benigno Perilla, the challengers said that they had not been fully or adequately consulted in the process of creating the national park and it therefore violated their right to Free Prior and Informed Consent.

With an apparently complex conflict unfolding between Yaigojé’s Indigenous Peoples and the area’s national park status–its ecological and social integrity held in the balance–a legal deadlock ensued. This situation persisted for three years, until January 2014, when in an unprecedented move, three judges from Colombia’s Constitutional Court made the decision to travel to the heart of the Colombian Amazon to hold a hearing and consult with communities first hand.

Jorge Iván Palacio, president of the court, explained the court’s decision to make the journey by stating that “there is no justice unless we know what they think in the communities.” The ensuing hearing thoroughly vindicated his observation.

Before 160 indigenous inhabitants from along the Apaporis River and the judges, Benigno Perilla publicly admitted that his and ACITAVA’s legal strategy was encouraged, organized and paid for by Cosigo Resources. In what would prove the critical turning point in the case, the indigenous members of ACITAVA who had supported the challenge made a public apology, said they had been misled and declared their support for the creation of the national park.

A NEW DAWN FOR INDIGENOUS-LED CONSERVATION

Although it has been more than another year coming, the Colombian Constitutional Court has ousted Cosigo and legitimized the declaration of Yaigojé Apaporis as a national park. The decision recognizes the authority of the area’s Indigenous Peoples and protects their fundamental rights to culture, identity and consultation.

The decision is regarded as a significantly positive precedent for future conflicts between mining operations, protected areas and their indigenous inhabitants, at a time when Colombia has declared mining to be in the national interest.

The judges found sufficient evidence of wrongdoing by Cosigo to ask Colombia’s Justice Minister to open an investigation into the company’s consultation processes and interactions with communities in the Yaigojé area. Recently published revisions to Colombia’s projects of national interest have seen Cosigo’s project removed from the list. The company is said to be reviewing its legal options.

Confirming the compatibility of indigenous resguardos and national parks, the court has also opened up the possibility for others to follow Yaigojé’s example and enhance the protection of their territories from destructive or unwanted “development.”

Since Yaigojé was declared a national park, and in spite of the legal wrangle over its future, ACIYA and local indigenous youths have been pioneering a powerful new conservation paradigm that values indigenous knowledge and places it at the root of national park management.

ACIYA’s work to find a method of conservation that both works for them and allows for close collaboration with Colombia’s national park authorities is the subject of a recent film and won the group the prestigious UNDP Equator Prize in 2014. Their approach stands in stark contrast to technocratic, neo-colonialist conservation norms founded on a misplaced belief in pristine, unmanaged wilderness. These have been criticized by Indigenous Peoples and rights groups for excluding and forcibly displacing indigenous communities, fencing them out of their own lands and so obstructing their right to practice their cultures.

As part of their program, 27 young indigenous leaders from nine communities in Yaigojé have engaged in a deep process of cultural research. Advised by their elders, they have documented, mapped and recorded their peoples’ traditional practices for safeguarding and conserving the forest. In the words of one researcher, the aim has been to “transmit traditional knowledge to the younger generations and protect our ancestral territory.” So far, they have succeeded in doing both.

The research produced by ACIYA will now be used to define the management of the Yaigojé Apaporis National Park, further legitimizing local indigenous knowledge systems that have protected the life-support capacities of this rainforest region for generation after generation.

“Indigenous people are the natural allies of the rainforest and the whole environmental movement,” says former director of Gaia Amazonas Martin Von Hildebrand. “They have the traditional knowledge, they are organized. We just need to support them with what they need to run their own territories.”

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 7, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy, The Solution: Resistance

By Intercontinental Cry

Territories of Life is a video toolkit with a purpose. It’s aim: to bring stories of resistance, resilience and hope to indigenous communities on the frontline of the global rush for land.

Produced by our friends at LifeMosaic, a non-profit based in Scotland, the Territories of Life toolkit consists of ten stories that were filmed in communities across Indonesia, Philippines, Guatemala, Ecuador, Colombia, Paraguay, Tanzania and Cameroon.

“The videos in the Territories of Life toolkit share inspirational stories of communities that are successfully organizing to defend their territories and their futures,” reads a press release from LifeMosaic. They include “The story of Maasai indigenous women in Tanzania who used awareness raising, protests and political pressure to lead a movement in defense of their territory; and the Misak indigenous people in Colombia who have developed and are carrying out their Plan de Vida, a long‐term vision for self-determined development.”

The toolkit also includes a few primers on land rights, land grabs, and common tactics that companies use to convince communities to accept and support their projects.

LifeMosaic goes on to say that, “The video toolkit and accompanying facilitators’ guide are intended to support indigenous peoples as they exercise their right to free, prior and informed consent; advocate for their rights; participate more actively in local spatial planning; and draw up village action plans for self‐determined development and for protecting their territories, forests and resources.”

It’s more than mere lip service. LifeMosaic is actively working with hundreds of local partners to facilitate the free distribution of Territories of Life to indigenous communities and supporting organizations around the world.

To order a copy of the toolkit, visit www.lifemosaic.net. If other groups request a DVD, LifeMosaic recommends a donation of $11 (£10). The videos can also be downloaded online at their website.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Sep 26, 2015 | Direct Action, Strategy & Analysis

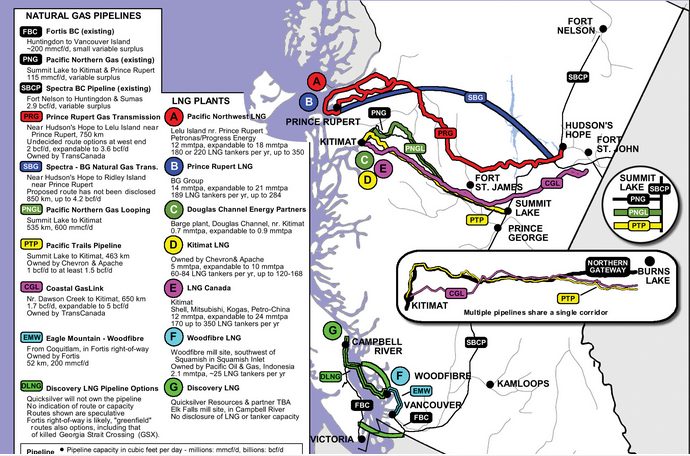

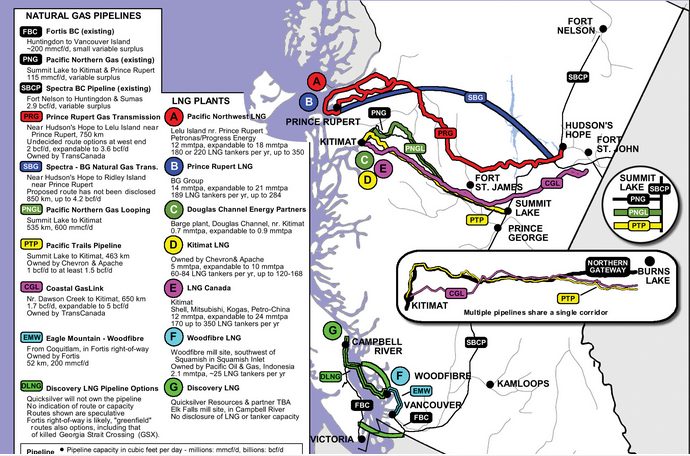

By Zoe Blunt, Vancouver Island Community Forest Action Network

In every part of the province, industry is laying waste to huge areas of wilderness – unceded indigenous land – for mining, fracking, oil, and hydroelectric projects. This frenzy of extraction is funneling down to the port cities of the Pacific and west to China.

Prime Minister Harper has stripped away legal options to stop this pillaging by signing a new resource trade agreement with China that trumps Canadian and local laws and indigenous rights. Not even a new government has the power to change this agreement for 31 years.

For mainstream environmental groups (and my lawyers, who were in the middle of a Supreme Court challenge to the trade agreement when Harper pre-empted them), it is a total rout. We are used to losing, but not like this.

The only light on the horizon is the rise of direct resistance. BC’s long history of large-scale grassroots action (and effective covert sabotage) is the foundation of this radical resurgence.

This time it’s different. This time we can write off the Big Greens. Tzeporah Berman, once the face of the Clayoquot Sound civil disobedience protests and now head of the Tar Sands Solutions Project, is publicly proposing that enviros capitulate in the hopes of a slightly greener pipeline apocalypse.

As usual, Berman and her kind are far behind the people they pretend to lead. Public opinion is hardening against pipelines and resource extraction.

But the question hangs over us like smoke from an approaching wildfire. How to stop it? The courts are hogtied. The law has no power. The people have no agency. This government simply brushes them aside and carries on. We get it. We’ve had our faces rubbed in it.

This is activist failure. The phase of the movement when most of the public is already on side, when we have filed all the lawsuits, taken to the streets in every city, overflowed every public hearing, and uttered every threat we can muster – and the end result is they are bulldozing this province from the tarsands straight to the coast.

This is the moment when we can expect activists, especially mainstream enviros, to become demoralized and quit or capitulate. Or delude themselves. Green groups are casting about for a strategy that will allow their donors to maintain false hope in a democratic solution. Some are still trying to raise money for legal challenges that can simply be overruled by the treaty with China.

But small cadres are preparing the second phase of the resistance. Indigenous groups are reclaiming territory and blocking development at remote river crossings, on strategic access roads, and in crucial mountain passes. Urban cells are locking down to gates, vandalizing corporate offices, and organizing street takeovers.

It’s a good start. But now we have to look at how to be effective against powerful adversaries with the full weight of the law and the police on their side. How will we protect the land and each other, when push comes to shove?

The new rules don’t change our strategy to bring down the enemy: kick them in the bottom line. The resource sector will wind tighter as competition to feed China intensifies. Profits are slim enough to start with – made up in volume – and investors are jittery already.

We urge our allies to heed the lessons of history. We don’t win by giving up. Tenacity, flexibility, and diversity of tactics turn back the invaders.

Celebrate the warriors. Raise that banner now, and we’ll find out soon enough who’s with us, and who’s looking to appease our new dictators.