by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 19, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

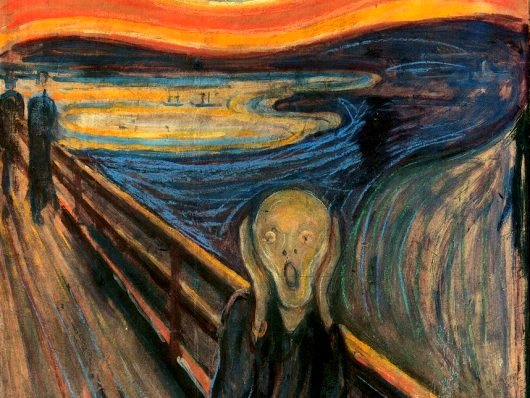

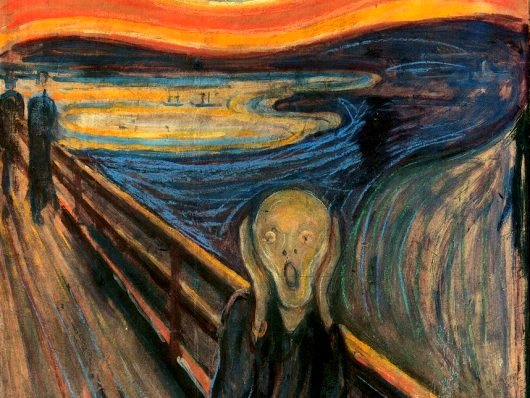

Featured image: animals steal the place of the Wretched of the Earth bloc at the People’s Climate March of Justice and Jobs. By Dominique Z Barron.

This is the twentieth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In this run of five posts, I am assessing the environmental movement using the twelve principles of strategic nonviolence conflict as described by Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler. [1] The principles are designed to address the major factors that contribute to the success or failure of nonviolent campaigns. Read more about the principles in the introductory post here. Read how the environmental movement relates to the first principle here, the second to fifth principles here and the sixth to the tenth here.

- Adjust offensive and defensive operations according to the relative vulnerabilities of protagonists

There are two basic postures taken in conflicts, offensive and defensive. Ackerman and Kruegler explain that the intent of a nonviolent campaign determines if it’s offensive or defensive. If a strike is intended to cripple a country and topple a government, then it is offensive. If the strike is intended to solidify a community and protect valuable resources, then it is defensive.

The mainstream environmental movement fails on this principle. Due to the scale of the issue, it has always been on the defensive. It comes up against industrial civilisation’s need to consume resources to continue functioning. The movement has limited numbers of people and self-limits itself on strategies and tactics. It is more on the defensive each day, and the scale and speed of destruction increases.

- Sustain continuity between sanctions, mechanisms, and objectives

This is based on Gene Sharp’s four mechanisms of change: conversion, accommodation, coercion and disintegration.

- Conversion results in the opponent being convinced of the merits of the campaign.

- Accommodation takes place when an opponent decides that a settlement is preferable to continued conflict.

- The opponent is coerced when they no longer have the ability to fight.

- Disintegration is an extreme form of coercion when the opponent ceases to exist as a political entity.

The mainstream environmental movement conforms to this principle. It varying strategies focus on conversion and accommodation of governments and it has maintained this approach. Unfortunately this is unlikely to be successful to meet the movement’s overall aim of a liveable planet in the medium term. Governments have clearly shown that environmental issues are not a serious concern compared to maintaining power, control and the continuation of capitalism. Any attempts so far at coercion have failed, due to limitations of the movement.

How did the environmental movement fair, based on the twelve principles? The three principles the environmental movement conformed to are securing access to critical material resources, maintaining nonviolent discipline, and sustaining continuity between sanctions, mechanisms, and objectives. The principles that the environmental movement partially met are expanding the repertoire of actions and attacking the opponent’s strategy for consolidating control.

The four it failed to meet are: formulating functional objectives; developing organisation strength; assessing events and options in light of levels of strategic decision making; and adjusting offensive and defensive operations according to the relative vulnerabilities of protagonists.

The principles that I judged were not applicable were cultivating external assistance; muting the impact of the opponents’ violent weapons; and alienating opponents from expected bases of support.

Overall the environmental movement seems capable of conducting a broad range of nonviolent actions and accessing material resources. Where it is weak is in recognising the need for, and developing, organisation strength, and operating strategically as a movement to achieve the overall goals and objectives.

As well as the issues listed above, there are other criticisms of the environmental movement. First, too much reliance on scientists who don’t understand politics and aren’t trusted. Second, the environmental movement has formulated its campaign in purely negative terms, focusing on looming global catastrophes. Third, the current denial that there were any concerns in the 1970’s and 1980’s about an imminent ice age. Fourth, the rise in the movement of a culture of intolerance, where dissent is demonised and asking questions about strategy and tactics is seen as disloyal. A fifth is the desire to be on the inside – those in the movement looking for support primarily from the affluent liberal class so framing messages and picking issues to appeal to a narrow section of the community instead of trying to build a broad base of support.

As well as these criticisms leveled at the mainstream environmental movement, there have also been some recent incidents that show racist and imperialist mentality in the movement. The December 2015 People’s Climate March for Justice and Jobs in London was meant to be led by a bloc made up of Indigenous people and people descended from communities from the Global South, called the Wretched of the Earth. But on the day of the march the march organisers tried to dilute this group’s message and make it palatable; banners made by indigenous people were covered up or removed; the place of indigenous, black and brown people was stolen and given away to people dressed as animals; and the march organisers twice called the police on this group. Read details here, here and here. There were similar issues with the People’s Climate March in Sydney that year.

Another incident was in September 2016 at a training camp at standing rock as part of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protests. A camp participant reported that outside white nonviolent trainers were attempting to teach protestors how to “de-escalate”; pulling young men (warriors) aside and chastising them for their anger; and telling them not to wear bandanas over their faces but to proudly be identified.

So there are issues around the environmental movement’s strategy, tactics, co-oping by corporate environmental organisations and racist and imperialist attitudes. For the movement to have any chance of success, it needs to start thinking more radically about what is needed to get results, rather than what those in the movement are comfortable with. We also need to show solidarity to those communities on the frontline of climate change. I do not believe it’s helpful to frame what’s happening to our world as an environmental or climate crisis. Industrial civilisation and capitalism are at war with life on earth – all life – and life needs a resistance movement with that analysis to respond.

Deep Green Resistance is advocating the use of force in defense of the living world. We believe that nonviolent direct action is an important tactic in our resistance, but it’s not the only tactic. Our movement must be clear on what we’re trying to achieve and what is possible with the limited time and resources available. Once we are clear on this, it will inform which tactics to employ.

This is the twentieth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler lay out twelve principle of strategic nonviolent conflict in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 13, 2017 | Lobbying

by Center for Biological Diversity

TUCSON, Ariz.— The Center for Biological Diversity and Congressman Raúl M. Grijalva, who serves as ranking member of the House Committee on Natural Resources, today sued the Trump administration over the proposed border wall and other border security measures, calling on federal agencies to conduct an in-depth investigation of the proposal’s environmental impacts.

Today’s suit, filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona, is the first targeting the Trump administration’s plan to vastly expand and militarize the U.S.-Mexico border, including construction of a “great wall.”

“Trump’s border wall will divide and destroy the incredible communities and wild landscapes along the border,” said Kierán Suckling, the Center’s executive director.

“Endangered species like jaguars and ocelots don’t observe international boundaries and should not be sacrificed for unnecessary border militarization. Their survival and recovery depends on being able to move long distances across the landscape and repopulate places on both sides of the border where they’ve lived for thousands of years.”

The lawsuit seeks to require the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and U.S. Customs and Border Protection to prepare a supplemental “programmatic environmental impact statement” for the U.S.-Mexico border enforcement program.

The program includes Trump’s proposed wall as well as road construction, off-road vehicle patrols, installation of high-intensity lighting, construction of base camps and checkpoints, and other activities. These actions significantly impact the borderlands environment stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, which is home to millions of people, endangered species like jaguars and Mexican gray wolves, and protected federal lands like Big Bend National Park and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument.

“American environmental laws are some of the oldest and strongest in the world, and they should apply to the borderlands just as they do everywhere else,” Grijalva said. “These laws exist to protect the health and well-being of our people, our wildlife, and the places they live. Trump’s wall — and his fanatical approach to our southern border — will do little more than perpetuate human suffering while irrevocably damaging our public lands and the wildlife that depend on them.”

Congressman Grijalva’s district is the largest Congressional district in Arizona and includes approximately 300 miles of the U.S./Mexico border.

If successful, today’s lawsuit would require the Trump administration to undertake a comprehensive review of the social, economic and environmental costs of the border wall.

Background

The National Environmental Policy Act requires that federal agencies conduct environmental review of a major federal action or program that significantly affects the quality of the human environment.

The Immigration and Naturalization Service — the precursor to the Department of Homeland Security — last updated the “programmatic environmental impact statement” for the U.S.-Mexico border enforcement program in 2001. That review identified the potential impacts of border enforcement operations, including limited border wall construction, on wildlife and endangered species in particular as a significant issue. The 2001 analysis was intended to be effective for five years but has never been updated.

In the 16 years since, the U.S.-Mexico border enforcement program and associated environmental impacts have expanded well beyond the predictions of that document, with deployment of thousands of new border agents, construction of hundreds of miles of border walls and fences, construction and reconstruction of thousands of miles of roads, installation of base camps and other military and security infrastructure, among numerous other actions.

During that same time, scientific understanding of the impacts of border walls and other border enforcement activities on wildlife and endangered species including jaguars, ocelots, Mexican gray wolves and cactus ferruginous pygmy owls has advanced significantly. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has also designated “critical habitat” under the Endangered Species Act within 50 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border for more than 25 species since the outdated 2001 analysis was prepared.

Meanwhile, the number of undocumented migrants moving through the southwestern borderlands is at a historic low, and the border is more secure than it’s ever been.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 9, 2017 | Lobbying

Featured image: The Barro Blanco Dam in the Province of Chiriqui, western Panama. The dam is complete and will begin operation within weeks, according to the government. The Ngäbe-Bugle have been opposed to the project since its inception. Photo by Camilo Mejia Giraldo

by Tracy Barnett / Intercontinental Cry

PANAMA CITY, Panama – The waters were rising again in Weni Bagama’s community when she headed to Panama City to meet with government officials about the flooding from the Barro Blanco hydroelectric dam.

Bagama was one of 10 people scheduled to speak April 4 at the first in a series of meetings on the problem of human rights violations against environmental defenders throughout the country. The meetings were requested by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights at a hearing on that subject last month in Washington, D.C. There are currently more than 90 recorded human rights cases related to environmental issues in Panama, according to the Ministry of the Environment.

Meanwhile, Maryknoll Sister Melinda Roper traveled to the meeting from the opposite end of Panama, the province of Darien, heading to the same April 4 meeting. She was another of the 10 people scheduled to speak.

Roper, whose wide-ranging work in Panama includes participation in a local environmental group called Alianza para un Mejor Darien (Alliance for a Better Darien), was there to speak about the government’s lack of response to the repeated threats to journalist Ligia Arreaga, who was forced to flee the country due to her reporting on the destruction of the wetlands of Matusaragatí.

More Flooding in Ngäbe Territory

The nearly two-decade fight to stop Barro Blanco has led to violent conflicts with the Ngäbe-Buglé people and drawn fire from human rights and environmental advocates internationally as an example of the misuse of carbon offset programs. Despite all of this, the dam was constructed anyway and last year the company began a “test flooding” that inundated parts of three villages.

Bagama, a leader of her native Ngäbe people and the resistance movement against the dam, continues to fight to save the villages and the Tabasará River, which is sacred to the Ngäbe. She had traveled to Washington, D.C., for the IACHR hearing on March 17, where she had taken some heart in the fact that the international commission requested the Panamanian government engage in dialogue with protesters. She attended the first follow-up meeting on April 4 with high hopes.

Sr. Melinda Roper, second from right, attended the meeting with government officials on behalf of Alianza para un Mejor Darien on April 3, where she spoke of the case of journalist Ligia Arreaga and the destruction of the Matusaragatí wetlands. Osvaldo Jordán, executive director of Alianza para Conservation y Desarrollo, is pictured fourth from the right. (Courtesy of Feliciano Santos)

Afterwards, though, she expressed frustration at the lack of a response of government officials to her pointed questions. Earlier, on March 27, some of those officials, including Vice Minister Salvador Sánchez, had traveled to her community of Kiad to begin talks with the three affected communities.

They met, but talks seemed to reach a stalemate, because residents wanted two conditions in order to move forward. First, the reservoir levels need to be lowered below the line of the autonomous territory (comarca) to allow a professional archaeological investigation of the petrogylphs that have been submerged. The petroglyphs are the Ngäbe’s most important ceremonial site and represent a crucial connection to their ancestors.

Second, they repeated their request for representatives of the Dutch and German development banks that financed the project to visit the Ngäbe communities affected by the reservoir. Bagama said she hopes that the investment banks’ presence will contribute to a workable solution. But by March 31, with no warning, the waters in the river again began to rise.

“I asked them [at the April 4 meeting], ‘How we can have a guarantee that this conversation, this approach, will have follow-through and respect when they have not even concretized anything and are filling the reservoir again?”

Bagama was told that the subject of Barro Blanco would be dealt with in a separate process. She then asked when the next meeting would take place and has not yet received an answer.

In Kiad, Panama, Weni Bagama makes her way up a hill that was once verdant, now covered in caked mud since the flooding from Barro Banco dam. (Tracy L. Barnett)

Mónica De León, director of communications for the government’s Office of Foreign Affairs, sent an institutional response to this reporter’s questions via email: “The Government of the Republic of Panama is holding talks with the representatives of the communities impacted by the Barro Blanco Hydroelectric Project, in order to promote actions that address the incompatibilities identified at the dialogue table.”

She referenced the March 27 meeting in Kiad “to agree on options for spaces and points of cultural veneration of communities impacted by the project and follow up on monitoring of water quality studies. It should be noted that the hydro has not entered operations, the test period is nearing completion and water remains at the lowest level.”

During the months-long “test period” for filling the reservoir, the community lost its generations-old food forest and most of the fish and shrimp in their river, the ancient petroglyphs that are an important ceremonial site, their roads to other communities, and several homes. In recent months the waters have dropped due to it being the dry season; the rainy season has not yet begun, so the rising waters have come as a surprise.

Barro Blanco made headlines late last year when it became the first development project to be deregistered under the U.N. Clean Development Mechanism, making the dam ineligible for issuing carbon offset credits. The Clean Development Mechanism is intended to encourage sustainable development in developing countries, but critics of the dam argued that it was anything but sustainable. Besides the fact that it would potentially displace more than 500 people and a cultural center in the comarca, the project would damage an important river ecosystem and a ceremonial and archaeological site that is vital to Ngäbe culture.

Work had continued apace on the dam despite international pressure and continued mass protests by the Ngäbe people, in which several people died and more were badly injured in confrontations with police. Now that the dam is finished and substantial parts of the communities are flooded, they fear what else will be lost in the imminent rainy season, and if the dam becomes fully operational.

There was no answer from the government regarding the request for a visit from the banks.

Paul Hartogsveld, Dutch Development Bank FMO press officer, wrote to this reporter: “FMO continues to emphasize the need for dialogue and consent between all parties involved. We respect the process and are awaiting the outcome. We do not foresee further action as this would possibly interfere with the negotiations between the government and the indigenous representation.”

A Wetlands Destroyed

Although the government has set aside 26,000 hectares of the approximately 68,000-hectare wetlands — the country’s most important — as protected area, a series of irregularities continue to plague the region, including massive land grabs by growers of industrial rice and oil palm.

Illegal canals have been constructed that are draining the wetlands, and the lagoon at its heart is beginning to run dry; 6,000 hectares belonging to the reserve have illegally been sold to private individuals, according to an ongoing lawsuit by the environmental ministry.

Roper considered the strong representation at the meeting by high officials from many government agencies, as well as the U.N.’s high commissioner on human rights, to be a good sign.

“My impression was that the atmosphere was one of clarity and openness on the part of almost all the people there to continue the process of dialog, creating a space perhaps every month for conversation to continue — realizing that there are many, many problems in Panama in terms of human rights violations, especially in relation to environmental problems,” said Roper.

“Of course it’s the type of meeting where you can make recommendations and you can establish context and dialog. It’s not a problem-solving meeting in the sense they would make a resolution to solve a specific problem, but I think it could work toward that.”

Another case presented at the April 4 meeting that continues to deteriorate, said Osvaldo Jordán, executive director of the Panamanian nonprofit Alianza para Conservación y Desarrollo (Alliance for Conservation and Development), is the development of Pedro González Island, where residents of African descent say law enforcement has arbitrarily detained them for opposing a foreign investor’s tourism project on lands they and their ancestors have inhabited for 300 years.

Despite the disappointment that Barro Blanco wasn’t addressed, attendees agreed that the meeting was a positive beginning to a new forum for addressing human rights violations against environmental defenders.

“I think it was positive in the sense that it allowed for a dialog,” said Jordán. “These are groups that were heavily oppressed, and their cases were ignored. So just making those cases visible and raising them to this level of public awareness is a step ahead. Unfortunately no clear answers were given and the danger is that this becomes catharsis — just a time for people to vent their frustrations without getting to any resolution. So we have to fight hard for that not to happen.”

Farah Urrutia, Director of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, responded to this reporter’s questions in an email, referencing the achievements of the meeting: the presence of high-level officials in various government agencies, as well as the Office of the Ombudsman, and an agreement to follow up with site visits to the problem areas and by organizing monthly meetings with environmental defenders.

“Finally, we believe that the climate of the [working group] is conducive to assess the possible presentation of a bill that can protect these groups,” she added.

Jordán agreed. “I think the meeting represented a positive direction, in particular the proposal of the ombudsman’s office to coordinate with the U.N. in trying to get a policy that will protect environmental defenders in Panama,” he said.

Meanwhile, Bagama is hopeful of receiving a phone call soon so that the conversations with the government can continue. Although she clarified — as she did at the April 4 meeting — that in her view, as of yet there is no formal dialog between the communities and the government, and there will be no dialog until their requests are met.

“If the government wants a conversation with the affected communities, they need to stop filling the reservoir,” she said. “If they do not stop the filling it, there is no conversation. It is regrettable and I don’t want it to happen, but that is what will happen if the government does not order to stop filling. They argue that they cannot do it, but I ask, ‘Who is in charge? The government or the companies? Who defends the rights?’ That is what we are seeing.”

[Tracy L. Barnett is an independent writer, editor and photographer specializing in environmental issues, indigenous rights and sustainable travel.]

An earlier version of this story appeared in Global Sisters Report.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 4, 2017 | Building Alternatives, Strategy & Analysis

by Helena Norberg-Hodge / Local Futures

While we mourn the tragedy that fear, prejudice and ignorance “trumped” in the US Presidential election, now is the time to go deeper and broader with our work. There is a growing recognition that the scary situation we find ourselves in today has deep roots.

To better understand what happened—and why—we need to broaden our horizons. If we zoom out a bit, it becomes clear that Trump is not an isolated phenomenon; the forces that elected him are largely borne of rising economic insecurity and discontent with the political process. The resulting confusion and fear, unaddressed by mainstream media and politics, has been capitalized on by the far-right worldwide.

Almost everywhere in the world, unemployment is increasing, the gap between rich and poor is widening, environmental devastation is worsening, and a spiritual crisis—revealed in addiction, domestic assaults, and suicide—is deepening.

From a global perspective it becomes apparent that these many crises—to which the rise of right-wing sentiments is intimately connected—share a common root cause: a globalized economic system that is devastating not only ecosystems, but also the lives of hundreds of millions of people.

How did we end up in this situation?

Over the last three decades, governments have unquestioningly embraced “free trade” treaties that have allowed ever larger corporations to demand lower wages, fewer regulations, more tax breaks and more subsidies. These treaties enable corporations to move operations elsewhere or even to sue governments if their profit-oriented demands are not met. In the quest for “growth,” communities worldwide have had their local economies undermined and have been pulled into dependence on a volatile global economy over which they have no control.

Corporate rule is not only disenfranchising people worldwide, it is fueling climate change, destroying cultural and biological diversity, and replacing community with consumerism. These are undoubtedly scary times. Yet the very fact that the crises we face are linked can be the source of genuine empowerment. Once we understand the systemic nature of our problems, the path towards solving them—simultaneously—becomes clear.

Trade unions, environmentalists and human rights activists formed a powerful anti-trade treaty movement long before Trump came on the scene. And his policies already show that he is about strengthening corporate rule, rather than reversing it.

Re-regulating global businesses and banks is a prerequisite for genuine democracy and sustainability, for a future that is shaped not by distant financial markets but by society. By insisting that business be place-based or localized, we can start to bring the economy home.

Around the world, from the USA to India, from China to Australia, people are reweaving the social and economic fabric at the local level and are beginning to feel the profound environmental, economic, social and even spiritual benefits. Local business alliances, local finance initiatives, locally-based education and energy schemes, and, most importantly, local food movements are springing up at an exponential rate.

As the scale and pace of economic activity are reduced, anonymity gives way to face-to-face relationships, and to a closer connection to Nature. Bonds of local interdependence are strengthened, and a secure sense of personal and cultural identity begins to flourish. All of these efforts are based on the principle of connection and the celebration of diversity, presenting a genuine systemic solution to our global crises as opposed to the fear-mongering and divisiveness of the dominant discourse in the media.

Moreover, localized economies boost employment not by increasing consumption, but by relying more on human labor and creativity and less on energy-intensive technological systems—thereby reducing resource use and pollution. By redistributing economic and political power from corporate monopolies to millions of small businesses, localization revitalizes the democratic process, re-rooting political power in community.

The far-reaching solution of a global to local shift can move us beyond the left-right political theater to link hands in a diverse and united people’s movement for secure, meaningful livelihoods and a healthy planet.

Republished with permission of Local Futures. For permission to repost this or other entries on the Economics of Happiness Blog, please contact info@localfutures.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 3, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the nineteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In this run of five posts, I am assessing the environmental movement using the twelve principles of strategic nonviolence conflict as described by Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler. [1] The principles are designed to address the major factors that contribute to the success or failure of nonviolent campaigns. Read more about the principles in the introductory post here. Read how the environmental movement relates to the first principle here and the second to fifth principles here.

- Attack the opponent’s strategy for consolidating control

This principle relates to Gene Sharp’s idea of undermining a regime’s sources of power (see post 6).

The mainstream environmental movement partially meets this principle. There are a small number of campaigns and groups that attempt to increase the economic costs of extractive industries, through occupation, blocking and sabotage. But with limited numbers of people willing to do this, the impact is minimum.

Fossil fuel divestment campaigns rely on businesses and institutions acting against their reason for being – concentrating wealth. So any company divesting from fossil fuels is going to be so small or marginal it won’t make any difference. Companies are legally obliged to maximise profits for their shareholders. Ninety companies are responsible for two thirds of greenhouse gas emissions since the start of industrial revolution. Coal companies have to produce coal. Oil companies have to produce oil. No matter how much we divest, if there is still demand for these things then they will continue to be extracted. The global economy cannot function without them. Ultimately, the divestment campaigns will only change the ownership of some shares from public institutions to private one.

Power and control over the population is maintained by a lack of access to land, which requires most of us to work jobs we don’t want to do, wasting our time and energy so we can afford food, shelter and heating. It’s hard work to make any money in the capitalist system, even for those who do have land, and it requires the use of industrial equipment, with the negative impacts this has on the land.

The most significant strategy for the state to maintain power and control is its willingness to use violence. Western governments pretend that they run democracies with police forces that are there to serve the public and use legitimate violence (see post 3). The mainstream environmental movement has completely failed to even identify this as a problem, let alone start thinking about how to tackle it.

- Mute the impact of the opponents’ violent weapons

Ackerman and Kruegler suggest a several options here: get out of harm’s way, confuse and fraternise with opponents, disable the weapons, prepare people for the worst effects of violence, and reduce the strategic importance of what may be lost to violence.

This principle is not really applicable in industrialised countries, because so far direct violence against environmental activists has been limited, in an attempt to continue the pretence of democracy. Activists have taken to filming the police at protests and demonstrations, to capture when the police step over the line. Violence against environmental activists is a serious problem in less-industralised countries.

- Alienate opponents from expected bases of support

This principle relates to Gene Sharp’s idea of “Political Jiu-Jitsu,” where violent states exposes what it is capable of and will to do to maintain its power and control (see post 6). For many of those following the conflict but sitting on the sidelines, this may result in them joining the fight against the state.

Governments in industrialised countries have learned that if their repression is too harsh, it radicalises people to a cause. So they now use little or no violence if possible and instead use much more subtle methods to control dissent. Therefore this principle is not applicable, but with repression on the gradual increase, that may soon change.

- Maintain nonviolent discipline

Ackerman and Kruegler argue that maintaining nonviolent discipline is not arbitrary or a moralistic choice, but instead is strategically advantageous. Although, they add that it’s not possible or desirable to morally, politically or strategically rule the use of force out. They recommend avoiding sabotage and demolition, while admitting nonviolent sabotage might be acceptable, if only to be done to prevent greater harms, with no harm to humans.

The mainstream environmental movement does conform to this principle. Nonviolence ideology is very strong across the movement and in most groups. When talking to mainstream environmentalists about the need to use force to defend ourselves and the planet, I generally get the “it won’t be successful as the state is too powerful” argument. Others say that the state uses violence so we shouldn’t, morally. Another argument I hear is concerned that using force may result in the state using heavy repression, which could hurt of kill the movement, people involved or their family and friends.

There are also a number of brave individuals outside the mainstream environmental movement that use sabotage to stop the destruction taking place.

- Assess events and options in light of levels of strategic decision making

Ackerman and Kruegler identify five levels of strategic decision making: policy, operational planning, strategy, tactics and logistics.

- Policy is similar to “grand strategy” – what and how shall we fight, how will we know if we’ve won or lost, what costs are willing to bear and inflict to meet our objective.

- Operation planning lays out how success is expected to occur – what nonviolent methods to use, and a vision of the steps necessary to reach a desired outcome.

- Strategy determines how a group will deploy its human and material assets – it adjusts constantly as things change.

- Tactics inform individual encounters or confrontations with opponents.

- Logistics refer to the whole range of tasks the support the strategy and tactic – including finances, resources, and necessary materials.

The mainstream environmental movement fails at the principle. Due to its broadness it has multiple “grand strategies” that include raising awareness, education, market-based responses such as carbon trading, living in alternative ways outside the system, and divestment campaigns. There is no coherent operational planning across the movement. Some groups and campaigns do follow the practice of developing strategies and tactics but most do not, and are instead reacting to the onslaught of this culture on the living world.

Many say that environmentalists need to frame the cause in a way that engages people. I believe the environmental movement has tried that in a number of ways. Taking fracking as an example: the poisoning of groundwater has motivated a large number of people to protest, but not enough to result in a mass movement.

So how is our movement going to convince a sufficient number of people that the global capitalist economy and industrial society need to end?

This is the nineteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler lay out twelve principle of strategic nonviolent conflict in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 22, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the eighteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In this run of five posts, I am assessing the environmental movement using twelve principles of strategic nonviolence conflict. [1] The principles are designed to address the major factors that contribute to the success or failure of nonviolent campaigns. Read more about the principles in the introductory post here. Read how the environmental movement relates to the first principle here.

- Develop organisation strength

Although some individuals can make a difference, successful resistance is carried out by groups. Nonviolent resistance organisations need to develop certain capabilities. They must adapt to changing situations, make decisions under pressure, and communicate these decisions to mobilisation. They need to be capable of concealments, dispersion and surprise. Ackerman and Kruegler describe three strata of organisation: leadership, operational corps, and the broad civilian population.

The mainstream environmental movement has failed to develop organisation strength. It has a large number of groups, but due to the broadness of the movement and multiple aims there is a distinct lack of organised structure and coordination. Individuals and groups in the mainstream environmental movement are generally left-leaning or follow an anarchist philosophy of decentralised organising. This has resulted in a movement of small groups that avoid structure and hierarchy, all focusing on their specific issue. This can have its advantages if a small local grassroots group is tackling a local problem, but is a serious weakness if trying to build a united movement to stop climate change and the destruction of the global biosphere.

Many in the movement are too busy squabbling over which reformist solution is best or which lifestyle choices and new technologies will allow their comfortable lives to continue. Unlike those on the right, who are very focused on their goal of maximising profits at any cost.

- Secure access to critical material resources

These are needed to ensure the physical survival of resisters and so they can carry out nonviolent actions. This principle is focused on a nonviolent conflict situation where resisters need to ensure they have the basic necessities of life so they can maintain the campaign until success.

The mainstream environmental movement does have access to critical material resources, although it has not been tested in a serious nonviolent conflict. Many in the movement are middle class in paid employment with access to funds and professional skills. Large parts of the environmental movement have also been co-opted by corporations resulting in ineffective Non-Government Organisations (NGOs).

- Cultivate external assistance

This is either direct or indirect support for the campaign from outside the immediate arena of conflict. It may be public acts of support, direct material aid; or third parties may launch sanctions of their own.

I do not think this principle is directly applicable to the mainstream environmental movement due to its international scope. Environmentally minded billionaires could be looked to, to provide this external assistance. Naomi Klein in her a book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate dedicates a chapter to exploring the contributions of Richard Branson, Warren Buffett, Bill Gates etc and find they are basically looking for technology to save the day.

- Expand the repertoire of sanctions

Gene Sharp lists 198 nonviolent methods. Ackerman and Kruegler suggest five questions to ask when choosing which methods to use:

- Which methods will allow the resisters to seize and retain the initiative?

- Are the methods easily replicable?

- Can the methods be performed at different times and places without special training and preparations? And can the methods be dispersed or concentrated at will?

- Do the methods make sense from an economy of force and risk versus return perspective?

- Are the methods being used in a planned sequence that will build momentum and maximize their impact, while also maintaining flexibility?

The mainstream environmental movement partly meets this principle in that it does use a wide range of nonviolent methods, that are replicable. But the movement preference for media stunts results in it failing to seize and retain the initiative or build momentum in any significant way. The environmental movement does not carry out many acts of omission (see the Taxonomy of Action diagram). It mostly focuses on the “Indirect Action” areas of the acts of commission such as lobbying, protests and symbolic actions, education and awareness raising, and support work and building alternatives. Of course it is up against corporate media and disinterested public, but nevertheless does little to actively confront or threaten the current power arrangements.

The number of people in the environmental movement who are willing to use nonviolent methods to challenge power are low, and because there is little focus on collective strategy or coordination, they fail to employ an economy of force. Also, the movement’s “politics of the comfort zone” culture (see post 13) mean that few are even willing to get arrested, let alone anything more serious. The movement certainly doesn’t have the numbers and popular support of, say, the 2010 French pension reform strikes. This movement had 3.5 million people at its height, and sadly that campaign had limited success.

On a positive note, there have been a number of recent mass actions that have had an effect. In 2015, 1500 people from across Europe entered a lignite mine in the Rhineland, Germany and shut it down. In May 2016, 300 people shut down Ffos-y-fran coal mine, the UK’s biggest mass trespass of a mine. Also in May 2016 over 3,500 people shut down Vattenfall’s Ende Gelände lignite coal operations in Germany in a mass action of civil disobedience. Coal trains, diggers, power plants were all disrupted.

This is the eighteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler lay out twelve principle of strategic nonviolent conflict in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century