by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 4, 2017 | Building Alternatives, Strategy & Analysis

by Helena Norberg-Hodge / Local Futures

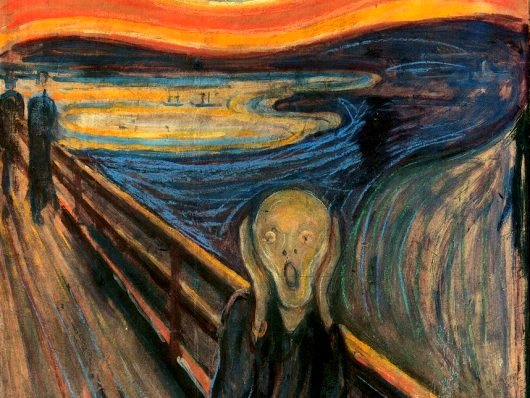

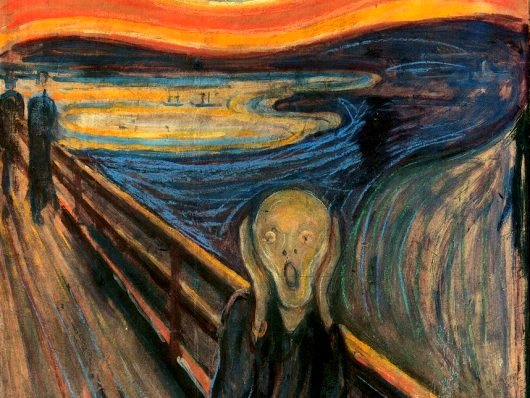

While we mourn the tragedy that fear, prejudice and ignorance “trumped” in the US Presidential election, now is the time to go deeper and broader with our work. There is a growing recognition that the scary situation we find ourselves in today has deep roots.

To better understand what happened—and why—we need to broaden our horizons. If we zoom out a bit, it becomes clear that Trump is not an isolated phenomenon; the forces that elected him are largely borne of rising economic insecurity and discontent with the political process. The resulting confusion and fear, unaddressed by mainstream media and politics, has been capitalized on by the far-right worldwide.

Almost everywhere in the world, unemployment is increasing, the gap between rich and poor is widening, environmental devastation is worsening, and a spiritual crisis—revealed in addiction, domestic assaults, and suicide—is deepening.

From a global perspective it becomes apparent that these many crises—to which the rise of right-wing sentiments is intimately connected—share a common root cause: a globalized economic system that is devastating not only ecosystems, but also the lives of hundreds of millions of people.

How did we end up in this situation?

Over the last three decades, governments have unquestioningly embraced “free trade” treaties that have allowed ever larger corporations to demand lower wages, fewer regulations, more tax breaks and more subsidies. These treaties enable corporations to move operations elsewhere or even to sue governments if their profit-oriented demands are not met. In the quest for “growth,” communities worldwide have had their local economies undermined and have been pulled into dependence on a volatile global economy over which they have no control.

Corporate rule is not only disenfranchising people worldwide, it is fueling climate change, destroying cultural and biological diversity, and replacing community with consumerism. These are undoubtedly scary times. Yet the very fact that the crises we face are linked can be the source of genuine empowerment. Once we understand the systemic nature of our problems, the path towards solving them—simultaneously—becomes clear.

Trade unions, environmentalists and human rights activists formed a powerful anti-trade treaty movement long before Trump came on the scene. And his policies already show that he is about strengthening corporate rule, rather than reversing it.

Re-regulating global businesses and banks is a prerequisite for genuine democracy and sustainability, for a future that is shaped not by distant financial markets but by society. By insisting that business be place-based or localized, we can start to bring the economy home.

Around the world, from the USA to India, from China to Australia, people are reweaving the social and economic fabric at the local level and are beginning to feel the profound environmental, economic, social and even spiritual benefits. Local business alliances, local finance initiatives, locally-based education and energy schemes, and, most importantly, local food movements are springing up at an exponential rate.

As the scale and pace of economic activity are reduced, anonymity gives way to face-to-face relationships, and to a closer connection to Nature. Bonds of local interdependence are strengthened, and a secure sense of personal and cultural identity begins to flourish. All of these efforts are based on the principle of connection and the celebration of diversity, presenting a genuine systemic solution to our global crises as opposed to the fear-mongering and divisiveness of the dominant discourse in the media.

Moreover, localized economies boost employment not by increasing consumption, but by relying more on human labor and creativity and less on energy-intensive technological systems—thereby reducing resource use and pollution. By redistributing economic and political power from corporate monopolies to millions of small businesses, localization revitalizes the democratic process, re-rooting political power in community.

The far-reaching solution of a global to local shift can move us beyond the left-right political theater to link hands in a diverse and united people’s movement for secure, meaningful livelihoods and a healthy planet.

Republished with permission of Local Futures. For permission to repost this or other entries on the Economics of Happiness Blog, please contact info@localfutures.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 3, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the nineteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In this run of five posts, I am assessing the environmental movement using the twelve principles of strategic nonviolence conflict as described by Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler. [1] The principles are designed to address the major factors that contribute to the success or failure of nonviolent campaigns. Read more about the principles in the introductory post here. Read how the environmental movement relates to the first principle here and the second to fifth principles here.

- Attack the opponent’s strategy for consolidating control

This principle relates to Gene Sharp’s idea of undermining a regime’s sources of power (see post 6).

The mainstream environmental movement partially meets this principle. There are a small number of campaigns and groups that attempt to increase the economic costs of extractive industries, through occupation, blocking and sabotage. But with limited numbers of people willing to do this, the impact is minimum.

Fossil fuel divestment campaigns rely on businesses and institutions acting against their reason for being – concentrating wealth. So any company divesting from fossil fuels is going to be so small or marginal it won’t make any difference. Companies are legally obliged to maximise profits for their shareholders. Ninety companies are responsible for two thirds of greenhouse gas emissions since the start of industrial revolution. Coal companies have to produce coal. Oil companies have to produce oil. No matter how much we divest, if there is still demand for these things then they will continue to be extracted. The global economy cannot function without them. Ultimately, the divestment campaigns will only change the ownership of some shares from public institutions to private one.

Power and control over the population is maintained by a lack of access to land, which requires most of us to work jobs we don’t want to do, wasting our time and energy so we can afford food, shelter and heating. It’s hard work to make any money in the capitalist system, even for those who do have land, and it requires the use of industrial equipment, with the negative impacts this has on the land.

The most significant strategy for the state to maintain power and control is its willingness to use violence. Western governments pretend that they run democracies with police forces that are there to serve the public and use legitimate violence (see post 3). The mainstream environmental movement has completely failed to even identify this as a problem, let alone start thinking about how to tackle it.

- Mute the impact of the opponents’ violent weapons

Ackerman and Kruegler suggest a several options here: get out of harm’s way, confuse and fraternise with opponents, disable the weapons, prepare people for the worst effects of violence, and reduce the strategic importance of what may be lost to violence.

This principle is not really applicable in industrialised countries, because so far direct violence against environmental activists has been limited, in an attempt to continue the pretence of democracy. Activists have taken to filming the police at protests and demonstrations, to capture when the police step over the line. Violence against environmental activists is a serious problem in less-industralised countries.

- Alienate opponents from expected bases of support

This principle relates to Gene Sharp’s idea of “Political Jiu-Jitsu,” where violent states exposes what it is capable of and will to do to maintain its power and control (see post 6). For many of those following the conflict but sitting on the sidelines, this may result in them joining the fight against the state.

Governments in industrialised countries have learned that if their repression is too harsh, it radicalises people to a cause. So they now use little or no violence if possible and instead use much more subtle methods to control dissent. Therefore this principle is not applicable, but with repression on the gradual increase, that may soon change.

- Maintain nonviolent discipline

Ackerman and Kruegler argue that maintaining nonviolent discipline is not arbitrary or a moralistic choice, but instead is strategically advantageous. Although, they add that it’s not possible or desirable to morally, politically or strategically rule the use of force out. They recommend avoiding sabotage and demolition, while admitting nonviolent sabotage might be acceptable, if only to be done to prevent greater harms, with no harm to humans.

The mainstream environmental movement does conform to this principle. Nonviolence ideology is very strong across the movement and in most groups. When talking to mainstream environmentalists about the need to use force to defend ourselves and the planet, I generally get the “it won’t be successful as the state is too powerful” argument. Others say that the state uses violence so we shouldn’t, morally. Another argument I hear is concerned that using force may result in the state using heavy repression, which could hurt of kill the movement, people involved or their family and friends.

There are also a number of brave individuals outside the mainstream environmental movement that use sabotage to stop the destruction taking place.

- Assess events and options in light of levels of strategic decision making

Ackerman and Kruegler identify five levels of strategic decision making: policy, operational planning, strategy, tactics and logistics.

- Policy is similar to “grand strategy” – what and how shall we fight, how will we know if we’ve won or lost, what costs are willing to bear and inflict to meet our objective.

- Operation planning lays out how success is expected to occur – what nonviolent methods to use, and a vision of the steps necessary to reach a desired outcome.

- Strategy determines how a group will deploy its human and material assets – it adjusts constantly as things change.

- Tactics inform individual encounters or confrontations with opponents.

- Logistics refer to the whole range of tasks the support the strategy and tactic – including finances, resources, and necessary materials.

The mainstream environmental movement fails at the principle. Due to its broadness it has multiple “grand strategies” that include raising awareness, education, market-based responses such as carbon trading, living in alternative ways outside the system, and divestment campaigns. There is no coherent operational planning across the movement. Some groups and campaigns do follow the practice of developing strategies and tactics but most do not, and are instead reacting to the onslaught of this culture on the living world.

Many say that environmentalists need to frame the cause in a way that engages people. I believe the environmental movement has tried that in a number of ways. Taking fracking as an example: the poisoning of groundwater has motivated a large number of people to protest, but not enough to result in a mass movement.

So how is our movement going to convince a sufficient number of people that the global capitalist economy and industrial society need to end?

This is the nineteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler lay out twelve principle of strategic nonviolent conflict in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 22, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the eighteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In this run of five posts, I am assessing the environmental movement using twelve principles of strategic nonviolence conflict. [1] The principles are designed to address the major factors that contribute to the success or failure of nonviolent campaigns. Read more about the principles in the introductory post here. Read how the environmental movement relates to the first principle here.

- Develop organisation strength

Although some individuals can make a difference, successful resistance is carried out by groups. Nonviolent resistance organisations need to develop certain capabilities. They must adapt to changing situations, make decisions under pressure, and communicate these decisions to mobilisation. They need to be capable of concealments, dispersion and surprise. Ackerman and Kruegler describe three strata of organisation: leadership, operational corps, and the broad civilian population.

The mainstream environmental movement has failed to develop organisation strength. It has a large number of groups, but due to the broadness of the movement and multiple aims there is a distinct lack of organised structure and coordination. Individuals and groups in the mainstream environmental movement are generally left-leaning or follow an anarchist philosophy of decentralised organising. This has resulted in a movement of small groups that avoid structure and hierarchy, all focusing on their specific issue. This can have its advantages if a small local grassroots group is tackling a local problem, but is a serious weakness if trying to build a united movement to stop climate change and the destruction of the global biosphere.

Many in the movement are too busy squabbling over which reformist solution is best or which lifestyle choices and new technologies will allow their comfortable lives to continue. Unlike those on the right, who are very focused on their goal of maximising profits at any cost.

- Secure access to critical material resources

These are needed to ensure the physical survival of resisters and so they can carry out nonviolent actions. This principle is focused on a nonviolent conflict situation where resisters need to ensure they have the basic necessities of life so they can maintain the campaign until success.

The mainstream environmental movement does have access to critical material resources, although it has not been tested in a serious nonviolent conflict. Many in the movement are middle class in paid employment with access to funds and professional skills. Large parts of the environmental movement have also been co-opted by corporations resulting in ineffective Non-Government Organisations (NGOs).

- Cultivate external assistance

This is either direct or indirect support for the campaign from outside the immediate arena of conflict. It may be public acts of support, direct material aid; or third parties may launch sanctions of their own.

I do not think this principle is directly applicable to the mainstream environmental movement due to its international scope. Environmentally minded billionaires could be looked to, to provide this external assistance. Naomi Klein in her a book This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate dedicates a chapter to exploring the contributions of Richard Branson, Warren Buffett, Bill Gates etc and find they are basically looking for technology to save the day.

- Expand the repertoire of sanctions

Gene Sharp lists 198 nonviolent methods. Ackerman and Kruegler suggest five questions to ask when choosing which methods to use:

- Which methods will allow the resisters to seize and retain the initiative?

- Are the methods easily replicable?

- Can the methods be performed at different times and places without special training and preparations? And can the methods be dispersed or concentrated at will?

- Do the methods make sense from an economy of force and risk versus return perspective?

- Are the methods being used in a planned sequence that will build momentum and maximize their impact, while also maintaining flexibility?

The mainstream environmental movement partly meets this principle in that it does use a wide range of nonviolent methods, that are replicable. But the movement preference for media stunts results in it failing to seize and retain the initiative or build momentum in any significant way. The environmental movement does not carry out many acts of omission (see the Taxonomy of Action diagram). It mostly focuses on the “Indirect Action” areas of the acts of commission such as lobbying, protests and symbolic actions, education and awareness raising, and support work and building alternatives. Of course it is up against corporate media and disinterested public, but nevertheless does little to actively confront or threaten the current power arrangements.

The number of people in the environmental movement who are willing to use nonviolent methods to challenge power are low, and because there is little focus on collective strategy or coordination, they fail to employ an economy of force. Also, the movement’s “politics of the comfort zone” culture (see post 13) mean that few are even willing to get arrested, let alone anything more serious. The movement certainly doesn’t have the numbers and popular support of, say, the 2010 French pension reform strikes. This movement had 3.5 million people at its height, and sadly that campaign had limited success.

On a positive note, there have been a number of recent mass actions that have had an effect. In 2015, 1500 people from across Europe entered a lignite mine in the Rhineland, Germany and shut it down. In May 2016, 300 people shut down Ffos-y-fran coal mine, the UK’s biggest mass trespass of a mine. Also in May 2016 over 3,500 people shut down Vattenfall’s Ende Gelände lignite coal operations in Germany in a mass action of civil disobedience. Coal trains, diggers, power plants were all disrupted.

This is the eighteenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler lay out twelve principle of strategic nonviolent conflict in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 15, 2017 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying

Featured image: Salomon Dunu, a Matsés man who survived the trauma of first contact, speaks to a Survival campaigner about the threat of oil exploration to his people. © Survival International

by Survival International

A Canadian oil company has told Survival International it will withdraw from the territory of several uncontacted tribes in the Amazon where it had been intending to explore for oil.

The company, Pacific E&P, had previously been awarded the right to explore for oil in a large area of the Amazon Uncontacted Frontier, a region of immense biodiversity which is home to more uncontacted tribes than anywhere else on Earth. It began its first phase of oil exploration in 2012.

The move follows years of campaigning by Survival International and several Peruvian indigenous organizations, including AIDESEP, ORPIO, and ORAU. ORPIO is suing the government over the threat of oil exploration.

Thousands of Survival supporters had protested by sending emails to the company’s CEO, lobbying the Peruvian government, and contacting the company through social media.

Survival also released an open letter, protesting against the threat of oil exploration, which was signed by Rainforest Foundation Norway and ORPIO. Sustained campaigning helped bring attention to the issue within Peru and around the world.

The Matsés have been dependent on and managed a large area of the Amazon Uncontacted Frontier for generations. © Christopher Pillitz

In a letter, Pacific E&P’s Institutional Relations and Sustainability Manager said that: “[The company] has made the decision to relinquish its exploration rights in Block 135… effective immediately… We wish to reiterate the company’s commitment to conduct its operations under the highest sustainability and human rights guidelines.”

At a tribal meeting in late 2016, a man from the Matsés tribe, which was forced into contact in the late 20th century, said: “I don’t want my children to be destroyed by oil and war. That’s why we’re defending ourselves… and why we Matsés have come together. The oil companies … are insulting us and we won’t stay silent as they exploit us on our homeland. If it’s necessary, we’ll die in the war against oil.”

Oil exploration involves sustained land invasion which can dramatically increase the risk of forced contact with uncontacted tribes. It leaves them vulnerable to violence from outsiders who steal their land and resources, and to diseases like flu and measles to which they have no resistance.

The announcement that it was not going ahead was welcomed by campaigners as significant in the fight to protect uncontacted peoples’ lives, lands and human rights.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said: “This is great news for the global campaign for uncontacted tribes and all those who wish to halt the genocide that has swept across the Americas since the arrival of Columbus. All uncontacted peoples face catastrophe unless their land is protected and we believe they are a vitally important part of humankind’s diversity and deserve their right to life to be upheld. We will continue to lead the fight to let them live.”

The region includes the Sierra del Divisor, or “Watershed Mountains,” a unique and highly biodiverse region known for its cone-shaped peaks. © Diego Perez

Background briefing

▪ Oil block 135 is within the proposed Yavarí Tapiche indigenous reserve. Peru’s national Indian organization AIDESEP has been calling for the creation of the reserve for over 14 years.

▪ Part of the oil concession is within the newly created Sierra del Divisor national park. The Peruvian government had awarded Pacific E&P rights to explore within the park.

▪ The Yavarí Tapiche region is part of the Amazon Uncontacted Frontier. This area straddles the borders of Peru and Brazil and is home to more uncontacted tribes than anywhere else in the world.

▪ Peru has ratified ILO 169, the international law for tribal peoples, which requires it to protect tribal land rights.

▪ We know very little about the uncontacted tribes in the area. Some are presumed to be Matsés, but there are other uncontacted nomadic peoples in the region.

The Amazon Uncontacted Frontier, a large area on the Peru-Brazil border that is home to the highest concentration of uncontacted tribes in the world. © Survival International

Uncontacted tribes are not backward and primitive relics of a remote past. They are our contemporaries and a vitally important part of humankind’s diversity. Where their rights are respected, they continue to thrive.

Their knowledge is irreplaceable and has been developed over thousands of years. They are the best guardians of their environment. And evidence proves that tribal territories are the best barrier to deforestation.

All uncontacted tribal peoples face catastrophe unless their land is protected. Survival International is leading the global fight to secure their land for them, and to give them the chance to determine their own futures.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 13, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the seventeenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

In the next four posts I will assess the environmental movement based on the twelve principles of strategic nonviolent conflict that Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler lay out in their book Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century. The principles are designed to address the major factors that contribute to the success or failure of nonviolent campaigns. The authors stress that the principles are exploratory rather than definitive. Read more about the principles in the introductory post to this run of posts here.

- Formulate functional objectives

Here we are looking for a clear goal and subordinate objectives. Five criteria help formulate functional objectives. They need to be concrete and specific enough to be achievable within a reasonable time frame. They need to include a diverse range of nonviolent methods. They need to maintain the main interests of the protesters rather than the adversary. They must attract the widest possible support within the relevant society. The objectives need to appeal to the values and interests of external parties to gain their support.

The mainstream environmental movement fails on this principle – formulate functional objectives. It does use a wide range of nonviolent methods, but fails to meet the other four criteria. Most critically, because it’s so large and diverse, it has no clear goal or objectives. I have run a number of workshops on this topic and none of the participants can agree on the goal and objectives of the environmental movement, and get confused between the goals and objectives of the whole movement or specific campaigns. Generally they all want a livable planet in the future and they seem to go about this by trying to convince everyone else that they need to take environmental issues seriously. This slow burn, paradigm shift strategy is not proving effective.

The movement also fails to determine its response based on what needs to happen in the material realm; versus, say, the taking-issues-seriously realm–in light of very pessimistic scientific forecasts–so fails to identify functional and appropriate objectives. Building a mass movement to transition to a sustainable society might have been possible if it had happened in the twentieth century, but we are now out of time and need drastic action to leave the fossil fuels in the ground.

The environmental movement also struggles because nature is currently viewed as property. So those that own parts of nature are legally allowed destroy them, with some minimal limitations. The more nature you own the more nature you can destroy. The environmental movement has been urging a more careful use of that property – environmental regulation. Attorney Thomas Linzey explains that successful movements take property like African American slaves or women before suffrage and convert them from the status of property, to a person or rights-bearing entity. There has never been an environmental movement that has focused on this, and anyone who has suggested it has been labeled radical or crazy. [1]

The environmental movement fails to attract wide support because it is telling people about a problem in the future that will mean they have to change their lives dramatically now. Of course there is also the whole issue of how the culture turn living systems into products to make money, but many don’t seem to notice this. This causes people’s denial reflexes to kick in so many find excuses not to think about it or act: “the science is wrong;” “the government will handle it;” “I recycle so I do my bit;” “they’ll find a technology to sort it out.” And because industrialised countries have such atomised societies with no community, then there is no moral code for anyone to answer to, just the made-up laws from the state.

There is much written about the psychological reasons why people fail to engage and act on climate change and environmental destruction, with seven books recently published on the subject.

The American Psychological Association task force identified six barriers to people acting:

- uncertainty about climate change;

- mistrust of scientists/officials;

- denial;

- undervaluing risks so deal with them later;

- lack of control – individual actions too small to make a difference;

- habit – ingrained behaviours are slow to change.

A recent report from ecoAmerica and the Center for Research on Environmental Decisions (CRED) at Columbia University’s Earth Institute — entitled “Connecting on Climate: A Guide to Effective Climate Change Communication,” identified seven psychological reasons that are stopping us from acting on climate change:

- psychological distance – too far in the future;

- finite pool of worry – people can only worry about a certain amount at once;

- emotional numbing – people get emotionally overloaded;

- confirmation bias and motivated reasoning – people seek out and retain information that matches their world view;

- defaults – people are overly biased in favor of the status quo;

- discounting – people value loss of money far in the future as less important that money now;

- ideology – political beliefs are deeply felt and highly emotional, even though it’s not clear how we come to these conclusions.

The phenomenon that psychologists call the “passive bystander effect” is relevant here. If people feel powerless they will deliberately maintain a level of ignorance so that they can claim that they know less than they do and wait for someone else to act first, to protect themselves.

Another recognised strategy to avoid dealing with climate change is to keep it out of your “norms of attention”. Basically people use selective framing so they don’t have to think about climate change most of the time. Opinion polls find that people define it as either a global issue, or far in the future. Others might say it’s only a theory or blame other countries. The fact that climate change is now seen as an environmental issue also resulted in it being excluded from their primary concerns or “norms of attention.” They can say “I’m not an environmentalist” or “The economy and jobs are more important.”

Without a functional, accurate analysis of a situation, there can be no way to formulate functional objectives to confront it. Because most peoples’ norms of attention are not focused on the actual gravity and immediacy of global warming, any organisation formulating functional objectives only accounts for a small number of actively engaged resisters, and what they can realistically accomplish.

More to follow.

Endnotes

- Thomas Linzey interviews with Derrick Jensen http://resistanceradioprn.podbean.com/e/resistance-radio-thomas-linzey-102013/ and http://prn.fm/resistance-radio-thomas-linzey-06-19-16/

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 10, 2017 | Lobbying

Featured image: The Matsés have denounced oil exploration in the proposed Yavarí Tapiche reserve, which is part of their ancestral lands. © Survival International

by Survival International

In an open letter to the Peruvian authorities, Survival International, Rainforest Foundation Norway and Peruvian indigenous organization ORPIO have denounced the Peruvian government’s failure to protect uncontacted tribes.

The organizations are calling for the government to create an indigenous reserve, known as Yavari-Tapiche, for uncontacted tribes along the Peru-Brazil border, and to put a stop to outsiders entering the territory.

In the letter the three organizations state: “Uncontacted tribes are the most vulnerable peoples on the planet. They have made the decision to be isolated and this must be respected…

“The Yavarí Tapiche region is home to uncontacted peoples. Despite knowing of their existence and enormous vulnerability, the government has failed to guarantee their protection…

“These tribal peoples face catastrophe unless their land is protected. Only by creating the proposed Yavarí Tapiche indigenous reserve and implementing effective protection mechanisms that prevent the entry of outsiders, will the indigenous people be given the chance to determine their own futures…

“We are also concerned about the government’s refusal to exclude oil exploration within the proposed reserve…. No exploration or exploitation of oil should ever be carried out on territories inhabited by uncontacted Indians…

“We believe that the oil company Pacific Stratus is poised to begin operations this year in areas where there are uncontacted tribes…

“By failing to both create the reserve and to rule out oil exploration, Peru is violating both domestic and international law…

“If the government does not act urgently to protect the uncontacted peoples of Yavarí Tapiche, we fear that they will not survive. Another tribe will disappear from the face of the earth, before the eyes of the world.”

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said: “We’ve repeatedly called for the Yavarí-Tapiche indigenous reserve to be created and for oil exploration to be ruled out, but the government has dragged its feet. The lives of uncontacted Indians are on the line but once again, economic interests take priority.”

Background Briefing

– The Yavarí Tapiche region is part of the Amazon Uncontacted Frontier. This area straddles the borders of Peru and Brazil and is home to more uncontacted tribes than anywhere else in the world.

– Pacific Stratus, part of Canadian oil company Pacific E&P, began its first phase of oil exploration in 2012, despite protests from indigenous organizations and Survival International. It is believed that the company will begin its second phase soon.

– Oil exploration is devastating for uncontacted tribes. Over 50% of the Nahua tribe died as a result of exploration in the 80s.

– The indigenous organization ORPIO is suing the government over the threat of oil exploration.

– National indigenous organization AIDESEP has been calling for the creation of the reserve for over 14 years.