Editor’s note: Online privacy is an essential layer of self-defense and security in our modern internet-driven world. This issue can be confusing and overwhelming. This article is aimed at beginners, and will provide a starting point for you to consider these issues and improve your security.

Why should I care about online privacy?

“I have nothing to hide. Why should I care about my privacy?”

Much like the right to interracial marriage, woman’s suffrage, and freedom of speech, we didn’t always have the right to privacy. Generations before ours fought for our right to privacy. Privacy is a human right inherent to all of us, that we are entitled to without discrimination.

But despite this, governments and corporations around the world regularly abuse our right to privacy for profit and power.

What should I do?

First, you need to make a plan.

Trying to protect all your data from everyone all the time is impractical, expensive, and exhausting. But, don’t worry! Security is a process, and by thinking ahead you can put together a plan that’s right for you. Security isn’t just about the tools you use or the software you download. Rather, it begins with understanding the unique threats you face, and how you can counter them.

Your Security Plan

Trying to protect all your data from everyone all the time is impractical and exhausting. But, have no fear! Security is a process, and through thoughtful planning, you can put together a plan that’s right for you. Security isn’t just about the tools you use or the software you download. It begins with understanding the unique threats you face and how you can counter those threats.

In computer security, a threat is a potential event that could undermine your efforts to defend your data. You can counter the threats you face by determining what you need to protect and from whom you need to protect it. This is the process of security planning, often referred to as “threat modeling.”

This guide will teach you how to make a security plan for your digital information and how to determine what solutions are best for you.

What does a security plan look like? Let’s say you want to keep your house and possessions safe. Here are a few questions you might ask:

What do I have inside my home that is worth protecting?

- Assets could include: jewelry, electronics, financial documents, passports, or photos

Who do I want to protect it from?

- Adversaries could include: burglars, roommates, or guests — as well as government or corporate agents.

How likely is it that I will need to protect it?

- Does my neighborhood have a history of burglaries? How trustworthy are my roommates/guests? Am I involved in risky political activity? What are the capabilities of my adversaries? What are the risks I should consider?

How bad are the consequences if I fail?

- Do I have anything in my house that I cannot replace? Do I have the time or money to replace these things? Do I have insurance that covers goods stolen from my home? Will our movement be harmed if the information or digital files I have are seized?

How much trouble am I willing to go through to prevent these consequences?

- Am I willing to buy a safe for sensitive documents? Can I afford to buy a high-quality lock? Do I have time to open a security box at my local bank and keep my valuables there? Can I use encryption to protect my files?

Once you have asked yourself these questions, you are in a position to assess what measures to take. If your possessions are valuable, but the probability of a break-in is low, then you may not want to invest too much money in a lock. But, if the probability of a break-in is high, you’ll want to get the best lock on the market, and consider adding a security system.

The risk that something bad might happen, and the potential level of harm should it happen, should both be taken into account.

Making a security plan will help you to understand the threats that are unique to you and to evaluate your assets, your adversaries, and your adversaries’ capabilities, along with the likelihood of risks you face.

How do I make my own security plan? Where do I start?

Security planning helps you to identify what could happen to the things you value and determine from whom you need to protect them. When building a security plan, answer these five questions:

- What do I want to protect?

- Who do I want to protect it from?

- How bad are the consequences if I fail?

- How likely is it that I will need to protect it?

- How much trouble am I willing to go through to try to prevent potential consequences?

Let’s take a closer look at each of these questions.

What do I want to protect?

An “asset” is something you value and want to protect. In the context of digital security, an asset is usually some kind of information. For example, your emails, contact lists, passwords and access to websites, instant messages, discussion forums, notes, plans, location, and files are all possible assets. Your devices may also be assets.

Make a list of your assets: data that you keep, where it’s kept, who has access to it, and what stops others from accessing it.

Who do I want to protect it from?

To answer this question, it’s important to identify who might want to target you or your information. A person or entity that poses a threat to your assets is an “adversary.” Examples of potential adversaries are your boss, your former partner, your business competition, your government, or a hacker on a public network.

Make a list of your adversaries, or those who might want to get ahold of your assets. Your list may include individuals, a government agency, or corporations.

Depending on who your adversaries are, under some circumstances this list might be something you want to destroy after you’re done security planning.

How bad are the consequences if I fail?

There are many ways that an adversary could gain access to your data. For example, an adversary can read your private communications as they pass through the network, or they can delete or corrupt your data.

The motives of adversaries differ widely, as do their tactics. A government trying to prevent the spread of a video showing police violence may be content to simply delete or reduce the availability of that video. In contrast, a political opponent may wish to gain access to secret content and publish that content without you knowing.

Security planning involves understanding how bad the consequences could be if an adversary successfully gains access to one of your assets. To determine this, you should consider the capability of your adversary. For example, your mobile phone provider has access to all your phone records. A hacker on an open Wi-Fi network can access your unencrypted communications. Your government might have stronger capabilities.

Write down what your adversary might want to do with your private data.

How likely is it that I will need to protect it?

Risk is the likelihood that a particular threat against a particular asset will actually occur. It goes hand-in-hand with capability. While your mobile phone provider has the capability to access all of your data, the risk of them posting your private data online to harm your reputation is low.

It is important to distinguish between what might happen and the probability it may happen. For instance, there is a threat that your building might collapse, but the risk of this happening is far greater in San Francisco (where earthquakes are common) than in Stockholm (where they are not).

Assessing risks is both a personal and a subjective process. Many people find certain threats unacceptable no matter the likelihood they will occur because the mere presence of the threat at any likelihood is not worth the cost. In other cases, people disregard high risks because they don’t view the threat as a problem.

Write down which threats you are going to take seriously, and which may be too rare or too harmless (or too difficult to combat) to worry about.

How much trouble am I willing to go through to try to prevent potential consequences?

There is no perfect option for security. Not everyone has the same priorities, concerns, or access to resources. Your risk assessment will allow you to plan the right strategy for you, balancing convenience, cost, and privacy.

For example, an attorney representing a client in a national security case may be willing to go to greater lengths to protect communications about that case, such as using encrypted email, than a family member who regularly emails funny cat videos.

Write down what options you have available to you to help mitigate your unique threats. Note if you have any financial constraints, technical constraints, or social constraints.

Security planning as a regular practice

Keep in mind your security plan can change as your situation changes. Thus, revisiting your security plan frequently is good practice.

Create your own security plan based on your own unique situation. Then mark your calendar for a date in the future. This will prompt you to review your plan and check back in to determine whether it’s still relevant to your situation.

Specific online privacy tools, methods, and apps

From here, you can start to consider and put in place specific protective measures. These might include things like:

- Shredding or burning old notes and files.

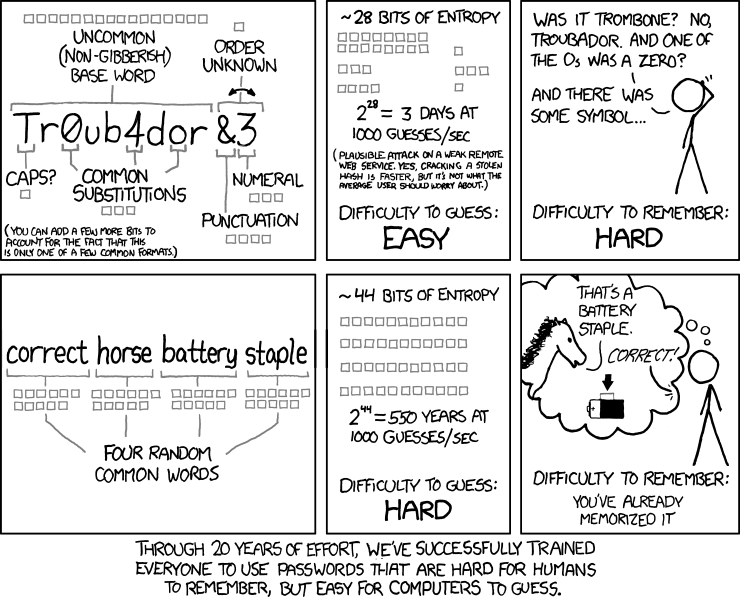

- Using a password manager and ensuring that your passwords are unique and strong.

- Enabling encryption on your phone, tablet, computer, and any other devices you own.

- Removing unused apps from your phone, tablet, or computer, and checking which apps have permission to access which features.

- Using a privacy-oriented web browser, such as Firefox, rather than Google Chrome.

- Use more-secure communication tools such as Signal, Wire, Protonmail, Tutanota, etc. rather than regular email, text messages, and phone calls.

- Enable end-to-end encryption if you use Zoom, or try a Zoom alternative such as Jitsi.

- Stop using non-private services such as Google Drive and Dropbox with end-to-end encrypted alternatives such as Skiff, Tresorit, Sync, and Cryptpad.

This article has been assembled from a mix of sources including the Electronic Frontier Foundation, PrivacyGuides.org, and our own knowledge here at the Deep Green Resistance News Service. We will publish additional guides on this topic in the future. This article is published under the Creative Commons-Share Alike Attribution 4.0 license.