by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Oct 23, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

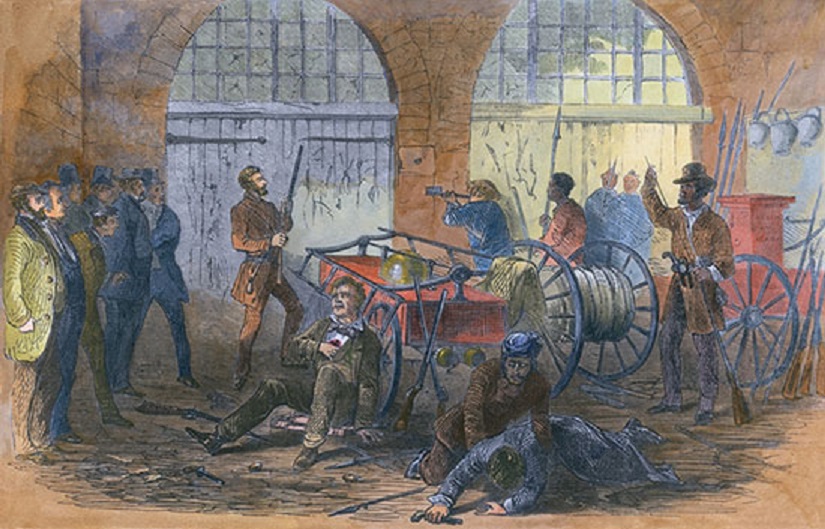

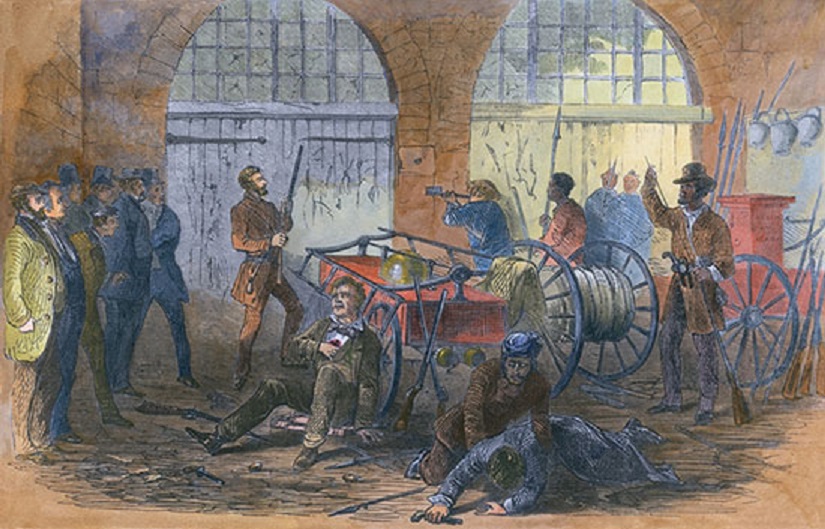

Featured image: the 1774 burning of the cargo ship Peggy Stewart, an escalation of the Boston Tea Party.

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Tactics and Targets” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

For me, nonviolence was not a moral principle but a strategy; there is no moral goodness in using an ineffective weapon.

—Nelson Mandela

Deeds, not words!

—Slogan of the Women’s Social and Political Union

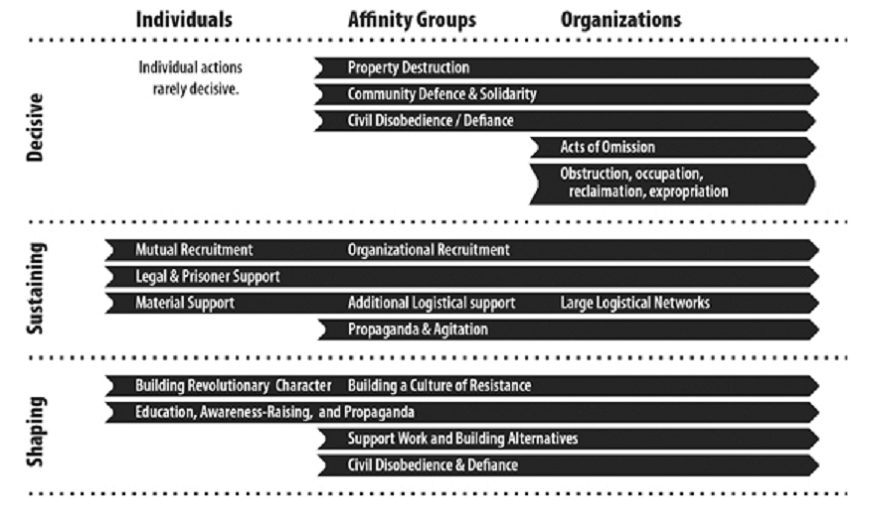

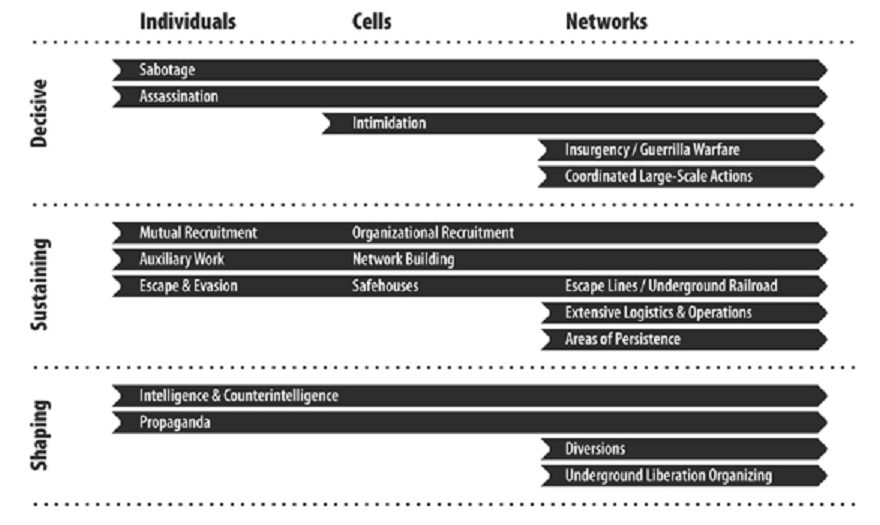

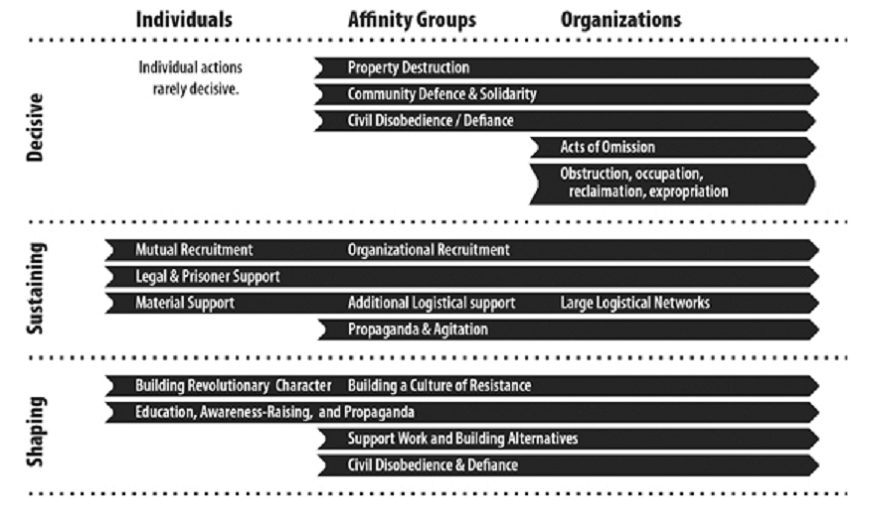

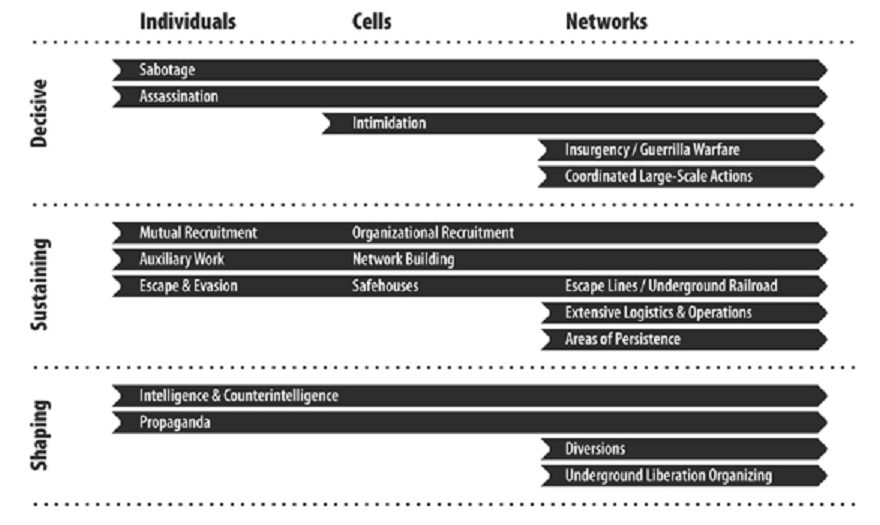

Recall that all operations—and hence all tactics—can be divided into three categories:

- Decisive operations, which directly accomplish the objective.

- Sustaining operations, which directly assist and support those carrying out decisive operations.

- Shaping operations, which help to create the conditions necessary for success.

Where tactics fall depends on the strategic goal. If the strategic goal is to be self-sufficient, then planting a garden may very well be a decisive operation, because it directly accomplishes the objective, or part of it. But if the strategic goal is bigger—say, stopping the destruction of the planet—then planting a garden cannot be considered a decisive operation, because it’s not the absence of gardens that is destroying the planet. It’s the presence of an omnicidal capitalist industrial system.

If one’s strategic goal is to dismantle that system, then one’s tactical categories would reflect that. The only decisive actions are those that directly accomplish that goal. Planting a garden—as wonderful and important as that may be—is not a decisive operation. It may be a shaping or sustaining operation under the right circumstances, but nothing about gardening will directly stop this culture from killing the planet, nor dismantle the hierarchical and exploitative systems that are causing this ecocide. Remember, the world used to be filled with indigenous societies which were sustainable and enduring. Their sustainability did not prevent civilization from decimating them again and again.

In this chapter we’ll break down aboveground and underground tactics into the three operational categories. For each class of operations, we’ll further break tactics down by scale for individuals, affinity groups, and larger organizations. This is summarized in Figures 13-1 and 13-2 below. As a rule, any tactic an individual can carry out can also be accomplished by a larger organization. So the tactics for each scale can nest into the next, like Russian matryoshka dolls.

Figure 13-1

Figure 13-2

Every resistance movement has certain basic activities it must carry out: things like supporting combatants, recruitment, and public education. These activities may be decisive, sustaining, or shaping, as shown in the illustration. And they may be carried out at different scales. Operations like education, awareness raising, and propaganda (shown under aboveground shaping) may occur across the range from the individual to large organizations. The scope of education may change as larger and larger groups take it on, but the basic activities are the same.

Other operations change as they are undertaken by larger groups and networks. Look in the underground tactics under sustaining. Individuals may use escape and evasion themselves, to start with. Once a cell is formed, they can actually run their own safehouse. And once cells form into networks, they can combine their safehouses to form escape lines or an entire Underground Railroad. The basic operation of escape and evasion evolves into a qualitatively different activity when taken on by larger networks. A similar dynamic is at work in recruitment; individuals are limited to mutual recruitment, but established groups can carry out organizational recruitment and training.

And, of course, some resistance units are too small to take on certain tasks, as we shall discuss. Individuals have few options for decisive action aboveground. Underground, they are limited in their sustaining operations, because secrecy demands that they limit contact with other actionists whom they could support. But once organizations become large enough, they can embrace new operations that would otherwise be out of their reach. Aboveground, large movements can use acts of omission like boycotts or they can occupy and reclaim land. And underground networks can use their spread for coordinated large-scale actions or even guerrilla warfare.

ABOVEGROUND TACTICS

Broadly speaking, aboveground tactics are those that can be carried out openly—in other words, where the gain in publicity or networking outweighs the risk of reprisals. Underground tactics, in contrast, are those where secrecy is needed to carry out the actions to avoid repression or simply to do the actions. The dividing line between underground and aboveground can move. Its position depends on two things: the social and political context, and the audacity of the resisters.

There have been times when sabotage and property destruction have been carried out openly. Conversely, there have been times when even basic education and organizing had to happen underground to avoid repression or reprisals. This means, explicitly, that when we use the term underground we do not necessarily mean acts of sabotage or violence: smuggling Jews out of Nazi Germany was an underground activity, and the Underground Railroad was by definition, er, underground. One of the most important jobs of radicals is to push actions across the line from underground to aboveground. That way, more people and larger organizations are able to use what was once a fringe tactic.1

Provoking open defiance of the laws or rules in question also impairs the ability of elites to exercise their power. The South African government, for example, was terrified that people of color in South Africa would simply stop obeying the law of the apartheid government. In even the most openly fascist state, the police force is still a minority of the population. If enough people disobey as part of their daily activities, then the country becomes ungovernable; there aren’t enough police to force everyone to perform their jobs at gunpoint.

When enough serious people have gathered to push a tactic back into the aboveground arena, those in power have few choices. If they continue to insist that the law be obeyed, resistance sympathizers may increasingly disregard any laws as dissidents begin to view the government as generally illegitimate—often a government’s worst nightmare. Or the government may offer concessions or change the law. Any of the above could be considered a victory. Usually governments strive to retain the image of control through selective concessions or legislation because the other road ends with civil unrest, revolution, or anarchy.

The cases of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X exemplifies how a strong militant faction can enhance the effectiveness of less militant tactics. In his book Pure Fire: Self-Defense as Activism in the Civil Rights Era, Christopher B. Strain explains that Martin Luther King Jr. pushed his agenda by using Malcolm X “to illustrate the alternative to legislative reform: chaos.… King would usually present the matter in terms of a choice: ‘We can deal with [the problem of second-class citizenship] now, or we can drive a seething humanity to a desperation it tried, asked, and hoped to avoid.’ … [He] suggested if white leaders failed to heed him ‘millions of Negroes, out of frustration and despair’ will ‘seek solace’ in Malcolm X, a development that ‘will lead inevitably to a frightening racial nightmare.’ ”2 But Strain emphasizes that King and Malcolm X were by no means enemies. “Despite their differing opinions, both men recognized that their brands of activism were complementary, serving to shore up the other’s weaknesses.”3

Some presume that Malcolm X’s “anger” was ineffective compared to King’s more “reasonable” and conciliatory position. That couldn’t be further from the truth. It was Malcolm X who made King’s demands seem eminently reasonable, by pushing the boundaries of what the status quo would consider extreme.

Pushing boundaries doesn’t have to involve underground property destruction or violence. Breaking antisegregation laws through lunch counter sit-ins, for example, pushed the limits of acceptability during the civil rights struggle. The second generation of suffragists, too, got tired of simply asking for what they wanted and started breaking the law. In both cases, the old guard activists were leery at first.

To be perfectly explicit: it isn’t just militants who can push the boundaries; even nonviolent groups can and should be pushing the envelope for militancy—vocally and through their actions—wherever and whenever possible. It’s hard to overstate the importance of this for any grand strategy of resistance. In this way, and many others, aboveground and underground activists are mutually supportive and work in tandem.

DECISIVE OPERATIONS ABOVEGROUND

Open property destruction is not always decisive. Take the Plowshares Movement activists, who break into military installations and use hammers and other tools to attack everything from soldiers’ personal firearms to live nuclear weapons, after which they wait and accept personal legal responsibility for their actions. There’s no doubt that this involves bravery—obviously it requires a lot of guts to take a sledgehammer to a hydrogen bomb—but these acts are not intended to be decisive. They are chiefly symbolic actions; neither the intent nor the effect of the action is to cause a measurable decrease in the military arsenal. (Presumably they could accomplish this if they really wanted to; anyone with the wherewithal to bypass military security and get within arm’s reach of a live nuclear warhead could probably do it more than once.)

In fact, open property destruction as a decisive aboveground tactic is historically rare. Remember, those in power view their property as being more important than the lives of those below them on civilization’s hierarchy. If large amounts of their property are being destroyed openly, they have few qualms about using violent retaliation. Because of this, situations where property can be destroyed openly tend to be very unstable. If those in power retaliate, the resistance movement either falters, shifts underground, or escalates. The Boston Tea Party is an excellent example. After the dumping of tea in December 1773, a boycott was imposed on British tea imports. In October 1774, the ship Peggy Stewart was caught attempting to breach the boycott while landing in Annapolis, Maryland. Protesters burned the ship to the waterline, a considerable escalation from the earlier dumping of tea. Within a year, mere property destruction segued into armed conflict and the Revolutionary War broke out.

Aboveground acts of omission are the more common tactical choice. An individual’s reduced consumption is not decisive, for reasons already discussed; in a society running short of finite resources like petroleum, well-meaning personal conservation may simply make supplies more available to those who would put them to the worst use, like militaries and corporate industry. But large-scale conservation could reduce the rate of damage slightly, and buy us more time to enact decisive operations, or, at least, when civilization does come down, leave us with slightly more of the world intact.

The expropriation or reclamation of land and materiel can be very effective decisive action when the numbers, strategy, and political situation are right. The Landless Workers Movement in Latin America has been highly successful at reclaiming “underutilized” land. Their large numbers (around two million people), proven strategy of reclaiming land, and political and legal framework in Brazil enable their strategy.

Many indigenous communities around the world engage in direct reoccupation and reclamation of land, especially after prolonged legal land claims, with mixed success. There are enough examples of success to suggest that direct reclamation can be successful, especially with wider support from both indigenous and settler communities. The specifics of conflicts like those at Kanehsatake and Oka, Caledonia, Gustafsen Lake, Ipperwash, and Wounded Knee (1973), are too varied to get into here. But it’s clear that indigenous land reclamations attack the root of the legitimacy—even the existence—of colonial states, which is why those in power respond so viciously to them, and why those struggles are so critical and pivotal for broader resistance in general.

SUSTAINING OPERATIONS ABOVEGROUND

Sustaining operations directly support resistance. For individuals aboveground, that means finding comrades through mutual recruitment or offering material or moral support to other groups. But individual mutual recruitment can be difficult (although this is easier if the recruiter in question is strongly driven, charismatic, well organized, persuasive, and so on). Affinity groups, with more people available to prospect, screen, and train new members, are able to recruit and enculturate very effectively. Individual recruiters have personality, but a group, even a small one, has a culture—hopefully a healthy culture of resistance.

Aboveground sustaining operations mostly revolve around solidarity, both moral and material. Legal and prisoner support are important ways of supporting direct action. So are other kinds of material support, fund raising, and logistical aid. The hard part is often building a relationship between supporters and combatants. There can be social and cultural barriers between supporters (say, settler solidarity activists) and those on the front lines (say, indigenous resisters). Indigenous activists may be tired of white people telling them how to defend themselves or perhaps simply wary of people whom they don’t know whether they should trust.

Propaganda and agitation supporting a particular campaign or struggle are other important sustaining actions. Liberation struggles like those in South Africa and Palestine have been defended internationally by vocal activists and organizers over decades. This propaganda has increased support for those struggles (both moral and material) and made it more difficult for those in power to repress resisters.

Larger organizations can undertake sustaining operations like fund raising and recruitment on a larger scale. They may also do a better job of training or enculturation. A single affinity group has many benefits, but can also be a bubble, a cultural fishbowl of people who come together because they believe the same thing. Being part of a larger network can mean that a new member gets a more well-rounded experience. Of course, the opposite can happen—dysfunctional large groups can quash ideological diversity. Often in “legitimate” groups that means quashing more radical, militant, or challenging beliefs in favor of an inoffensive liberal approach.

The converse problem is factionalism. There’s a difference between allowing internal dialogue and dissent, on one hand, and having acrimonious internal conflicts (like in the Black Panthers or the Students for a Democratic Society), on the other. The larger an organization is the harder it is to walk the line between unity and splintering (especially when the COINTELPRO types are trying hard to destroy any effective operation).

Larger organizations have a better capacity for sustaining operations (and decisive operations, for that matter) than individuals and small groups, but they rarely apply it effectively. Internal conflicts limit operations to the lowest common denominator: the lowest risk, the lowest level of internal controversy, and the lowest level of effectiveness. The big green and big leftist organizations will only go as far as holding press conferences and waving signs. Meanwhile, indigenous people who are struggling (often at gunpoint) to defend and reclaim their lands are ignored if they act outside the government land claims process. Tree sitters, even those who are avowedly nonviolent, get ignored by the big green organizations when police and loggers come in to attack them. The big organizations almost always fail to deploy their resources for sustaining operations when and where they are needed most. On a moral level, that’s deeply deplorable. On a strategic level, it’s unspeakably stupid. On a species and planetary level, it’s simply suicidal.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be that way. Effective resistance movements in history are usually composed of a cross section of many different organizations on many different scales, performing the different tasks best suited to them, and larger organizations are an important part of that. History has shown that it’s possible for large organizations to operate in solidarity and with foresight. Even if they don’t actually carry out decisive operations themselves, large aboveground organizations can offer incredibly important support.

SHAPING OPERATIONS ABOVEGROUND

Most day-to-day aboveground resistance actions are shaping operations of one kind or another. But many actions could be sustaining or shaping operations, depending on the context. Building a big straw-bale house out in the country would be considered a shaping operation if the house were built simply for the purpose of building a straw-bale house. But if that building were used as a retreat center for resistance training, it might then become part of sustaining operations. Consider the Black Panthers. A free breakfast program for children that was devoid of political content would have been a charity or perhaps mutual aid. A breakfast program integrated within a larger political strategy of education, agitation, and recruitment became a sustaining operation (as well as a threat to the state).

One of the most important shaping operations is building a culture of resistance. On an individual level, this might mean cultivating the revolutionary character—learning from resisters of the past, and turning their lessons into habits to gain the psychological and analytical tools needed for effective action. Building a culture of resistance goes hand in hand with education, awareness raising, and propaganda. It also ties into support work and building alternatives, especially concrete political and social alternatives to the status quo. As always, every action must be tied into the larger resistance strategy.

Most large organizations focus on shaping operations without making sure they are tied to a larger strategy. They try to raise awareness in the hopes that it will lead indirectly to change. This can be a fine choice if made deliberately and intelligently. But I think that most progressive organizations eschew decisive or sustaining operations because they simply don’t consider themselves to be resistance organizations; they identify strongly with those in power and with the culture that is destroying the planet. They keep trying to convince those in power to please change, and it doesn’t work, and they fail to adjust their tactics accordingly. The planet keeps dying, and people drop out of doing progressive work by the thousands, because it so often doesn’t work. We simply don’t have time for that anymore. We need a livable planet, and at this point a livable planet requires a resistance movement.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Oct 4, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

Resistance is not one-sided. For any strategy resisters can come up with, those in power will do whatever they can to disrupt and undermine it. Any strategic process—for either side—will change the context of the strategy. A strategic objective is a moving target, and there is an intrinsic delay in implementing any strategy. The way to hit a moving target is by “leading” it—by looking slightly ahead of the target. Don’t aim for where the target is; aim for where it’s going to be.

Too often we as activists of whatever stripe don’t do this. We often follow the target, and end up missing badly. This is especially clear when dealing with issues of global ecology, which often involve tremendous lag time. We’re worried about the global warming that’s happening now, but to avert current climate change, we should have acted thirty years ago. Mainstream environmentalism in particular is decades behind the target, and the movement’s priorities show it. The most serious mainstream environmental efforts are for tiny changes that don’t reflect the seriousness of our current situation, let alone the situation thirty years from now. They’ve got us worried about hybrid cars and changing lightbulbs, when we should be trying to head off runaway global warming, cascading ecological collapses, the creation of hundreds of millions of ecological refugees or billions of human casualties, and the social justice disasters that accompany such phenomena. If we can’t avert global ecological collapse, then centuries of social justice gains will go down the toilet.

It’s worth spelling this out. There have been substantial improvements in humans rights in recent decades, along with major social justice concessions in many parts of the world. Much of this progress can be rightly attributed to the tireless work of social justice advocates and extensive organized resistance. But look at, for example, the worsening ratio between the income of the average employee and the average CEO. The economy has become less equitable, even though the middle rungs of income now have a higher “standard of living.” And all of this is based on a system that systematically destroys natural biomes and rapidly draws down finite resources. It’s not that everyone is getting an equal slice of the pie, or even that the pie is bigger now. If we’re getting more pie, it’s largely because we’re eating tomorrow’s pie today. And next week’s pie, and next month’s pie.

For example, the only reason large-scale agriculture even functions is because of cheap oil; without that, large-scale agriculture goes back to depending on slavery and serfdom, as in most of the history of civilization. In the year 1800, at the dawn of the industrial revolution, close to 80 percent of the human population of this planet was in some form of serfdom or slavery.51 And that was with a fraction of the current human population of seven billion. That was with oceans still relatively full of fish, global forests still relatively intact, with prairie and agricultural lands in far better condition than they are now, with water tables practically brimming by modern standards. What do you think is going to happen to social justice concessions when cheap oil—and hence, almost everything else—runs out? Without a broad-based and militant resistance movement that can focus on these urgent threats, the year 1800 is going to look downright cheerful.

If we want to be effective strategists, we must be capable of planning for the long term. We must anticipate changes and trends that affect our struggle. We must plan and prepare for the changing nature of our fight six months down the road, two years down the road, ten years down the road, and beyond.

We need to look ahead of the target, but we also need to plan for setbacks and disruptions. That’s one of the reasons that the strategy of protracted popular warfare was so effective for revolutionaries in China and Vietnam. That strategy consisted of three stages: the first was based on survival and the expansion of revolutionary networks; the second was guerrilla warfare; and the third was a transition to conventional engagements to decisively destroy enemy forces. The intrinsic flexibility of this strategy meant that revolutionaries could seamlessly move along that continuum as necessary to deal with a changing balance of power. It was almost impossible to derail the strategy, since even if the revolutionaries faced massive setbacks, they could simply return to a strategy of survival.

How does anyone evaluate a particular strategy? There are several key characteristics to check, based on everything we’ve covered in this chapter.

Objective. Does the strategy have a well-defined and attainable objective? If there is no clear objective there is no strategy. The objective doesn’t have to be a static end point—it can be a progressive change or a process. However, it should not be a “blank or unrepresentable utopia.”

Feasibility. Can the organization get from A to B? Does the strategy have a clear path from the current context to the desired objective? Does the plan include contingencies to deal with setbacks or upsets? Does the strategy make use of appropriate strategic precepts like the nine principles of war? Is the strategy consonant with the nature of asymmetric conflict?

Resource Limitations. Does the movement or organization have the number of people with adequate skills and competencies required to carry out the strategy? Does it have the organizational capacity? If not, can it scale up in a reasonable time?

Tactics. Are the required tactics available? Are the tactics and operations called for by the plan adequate to the scale, scope, and seriousness of the objective? If the required tactics are not available or not being implemented currently, why not? Is the obstacle organizational or ideological in nature? What would need to happen to make the required tactics available, and how feasible are those requirements?

Risk. Is the level of risk required to carry out the plan acceptable given the importance of the objective? Remember, this goes both ways. It is important to ask, what is the risk of acting? as well as what is the risk of not acting? A strategy that overreaches based on available resources and tactics might be risky. And, although it may seem counterintuitive at first, a strategy that is too hesitant or conservative may be even more risky, because it may be unable to achieve the objective. If the objective of the strategy is to prevent catastrophic global warming, taking serious action may indeed seem risky—but the consequences of insufficient action are far more severe.

Timeliness. Can the plan accomplish its objective within a suitable time frame? Are events to happen in a reasonable sequence? A strategy that takes too long may be completely useless. Indeed, it may be worse than useless, and become actively harmful by drawing people or resources from more effective and timely strategic alternatives.

Simplicity and Consistency. Is the plan simple and consistent? The plan should not depend on a large number of prerequisites or complex chains of events. Only simple plans work in emergencies. The plan itself must be explained in a straightforward manner without the use of weasel words or vague or mystical concepts. The plan must also be internally consistent—it must make sense and be free of serious internal contradictions.

Consequences. What are the other consequences or effects of this strategy beyond the immediate objective and operations? Might there be unintended consequences, reprisals, or effects on bystanders? Can such undesirable effects be limited by adjusting the strategy? Does the value of the objective outweigh the cost of those consequences?

A solid grand strategy is essential, but it’s not enough. Any strategy is made out of smaller tactical building blocks. In the next chapter, “Tactics and Targets,” I outline the tactics that an effective resistance movement to stop this culture from killing the planet might use, and discuss how such a movement might select targets and plan effective actions.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 23, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

This shift toward more militant defiance of slavery was all wonderful, of course. And it certainly increased the success of the Underground Railroad if a slave catcher knew that a trip into strongly abolitionist areas might end with a bullet in his chest. But, again, there was a problem. Even this rapidly growing and increasingly defiant abolitionist movement had not been able to successfully challenge the institution of slavery itself. The situation continued to get worse. Writes Stewart, “More than two decades of peacefully preaching against the sin of slavery had yielded not emancipation but several new slave states and an increase of over half a million held in bondage, trends that seemingly secured a death grip by the ‘slave power’ on American life.”41 Cotton agriculture in the South often destroyed the landbase, and that, combined with a growing slave population, meant that it was profitable—according to some historians, even imperative—that slaveholders expand westward in order to maintain the slave economy. Each new slave state shifted the balance of political power in the Union even more toward slavery.

Enter John Brown, an ardent abolitionist and deeply moral man who had clashed with proslavery militants on several occasions before. Brown, a wool grower by trade, had fought in the struggle to make the new state of Kansas an antislavery state. He was apparently not much interested in making speeches, and thought little of rhetoric alone given the seriousness of the situation. Brown was frustrated with mainstream abolitionists, reportedly exclaiming, “These men are all talk. What we need is action—action!”

And action was exactly what he had in mind. In 1858, Brown ran a series of small raids from Kansas into Missouri, liberating slaves and stealing horses and wagons. He helped bring the liberated slaves to Canada, but his main plan was much more daring. Secretly raising funds from wealthy abolitionist donors, buying arms, and training a small group of paramilitary recruits, Brown planned a raid on the armory at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. The plan was simple. Brown and his troops would raid the armory, which contained tens of thousands of small arms. They would steal as many arms as they could, then liberate and arm the slaves in the area. They would head south, operating as guerrillas, liberating and arming slaves and fighting only in self-defense. Brown hoped for a movement that would grow exponentially as they moved into the Deep South, a cascade of action that would unravel and destroy the institution of slavery itself.

Although some historians—especially those impugning Brown—have considered him an insurrectionist, that’s not an accurate reflection of his intended strategy. Brown’s biographer, Louis A. DeCaro, has discussed this very fact: “Brown nowhere planned insurrection, which is essentially an armed uprising with the intention of eliminating slave masters. Brown planned an armed defensive campaign. His intention was to lead enslaved people away from slavery, arm them to fight defensively while they liberated still more people, fighting in small groups in the mountains, until the economy of slavery collapsed. Brown did not believe in killing unless it was absolutely necessary.”42

Tragically, things were not to go as planned. Part of the problem was numbers. While a draft plan for the Harpers Ferry raid called for thousands of men, on the day of the raid Brown had only twenty-one, both white and black. In an unusual situation for resistance fighters, Brown had far more guns than men. From Northern abolition societies, Brown had received about ten carbines (short rifles) for each fighter available. Nonetheless, Brown, deeply driven, decided to proceed.

At first the raid went smoothly. They easily entered the town of Harpers Ferry, cut the telegraph wires, and captured the armory. But Brown made a tactical error—the worst tactical error a guerrilla can make—by failing to seize the arms and move on as soon as possible. As a result, local militia were soon firing on the armory from the town while the militants remained inside. After continuing exchanges of fire and several deaths, US Marines under the command of Robert E. Lee arrived, surrounding and then storming the armory. Five of Brown’s fighters escaped, ten were killed, and the rest captured. Those captured were imprisoned and stood trial. John Brown and five others were subsequently hanged.

It’s extremely important to understand why the raid failed. The problem was tactical, rather than strategic in nature. Although he was unsuccessful, even his enemies at the time said that “it was among the best planned and executed conspiracies that ever failed.”43 In fact, even on the tactical level Brown’s planning was excellent. But instead of employing the hit-and-run tactics asymmetric forces depend on, Brown got bogged down in the armory. According to biographer Louis A. DeCaro, “The reason the raid did not succeed was because he paid too much concern to his hostages, including some whining slave masters, and undermined himself in trying to negotiate with them.” Furthermore, rather astonishingly, DeCaro notes that Brown even allowed “his prisoners to go home and see their families under guard and send out for their breakfast.”44 Indeed, Brown was in Harpers Ferry for almost two days before the marines arrived. According to DeCaro: “Had he kept to his own plan and schedule, he and his fugitive allies would have almost walked away from Harper’s Ferry without facing any significant opposition, and could have easily retreated to the mountains as planned. Contrary to the notion that he was a crazy man and a killer, it seems that John Brown was actually too tender-hearted and still hoped to resolve some of the issue by negotiation. This was his greatest error.”45

News of the raid spread swiftly. The knee-jerk response among many abolitionists and their sympathizers was one of contempt for Brown’s actions. Even Lincoln (perhaps afraid of offending the South) called him a “misguided fanatic.” Henry David Thoreau, notably, was one of the few who immediately sprang to Brown’s defense. He begged his fellow citizens to listen: “I hear many condemn these men because they were so few. When were the good and the brave ever in a majority?”46 (Now is a good time to ask that question of ourselves and our allies, especially if we are waiting for someone else to act.)

DeCaro notes that Brown’s reputation in history has been consistently attacked and “the ‘facts’ of his case have been mediated from slave masters, pro-slavery people, and pacifists.”47 (Those in the latter category will hopefully find it relevant, if embarrassing, that they are lumped in with such dreadful company.) But not everyone has been so easily convinced that Brown was wrongheaded. Malcolm X, not surprisingly, had great respect for John Brown and little patience for white liberals who criticized his methods. “John Brown … was a white man who went to war against white people to help free slaves. And any white man who is ready and willing to shed blood for your freedom—in the sight of other whites, he’s nuts.” In other words, those who hate Brown do so in large part because he was a “race traitor.”

The raid on Harpers Ferry increased tensions between the North and South. Some historians rank it among the proximal causes of the Civil War. This is ironic, as Brown despised unnecessary bloodshed, and, like many at the time, was aware that a war between North and South was very likely looming. It was his hope that his strategy of guerrilla warfare would end the slave economy while averting a civil war, which could be even bloodier. It’s possible that, had he been more ruthless, he might have succeeded. His hesitation to be ruthless, then, may have resulted in a much greater number of deaths. Brown’s problem, as with many of those who fight injustice, was that he was simply too nice, even when dealing with vicious oppressors. Brown himself realized this too late. On the day he was hanged he wrote the following: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.”48

Outright Civil War

Brown’s failed attack was a flashpoint for the rising strain between North and South, and outright Civil War shortly followed. This is not the place to discuss the full history of the Civil War or all its causes, but there are a few points that are relevant to understanding how outright Civil War impacted resistance. Many people have been taught that the Civil War was “fought to end slavery,” but this is not true. Social justice was not a main driving force behind the Civil War, and prior to the outbreak of hostilities, Abraham Lincoln insisted that slavery was a choice for each state to make. It might be more accurate to say that the Civil War was precipitated by the growth of “slave power” (that is, the power of slaving-holding states) and by the tensions between conflicting economic and political institutions. The immediate cause of the Civil War was the secession of slave-holding states into the Confederacy, which Abraham Lincoln would not allow.

The outbreak of Civil War (and especially the invasion of the Confederacy by Union forces) resulted in two distinct changes for abolitionists. First, slave resistance in the South was vastly increased, and second, many Northerners who were not abolitionists were forced to come face to face with slavery.

The impact of the Civil War on slave resistance was extensive even where armed conflict was not yet occurring. Many slaves attempted escape to get across Union lines where they would be ostensibly free, and many of those escapees joined the Union army to fight for the end of the Confederacy and the end of slavery. But even those slaves who did not run were roused to active resistance—or at least withdrawal of their labor. As in France in 1943, more and more slaves began to resist when it became clear that the slave owners might lose.

Historian Bruce Levine notes that:

The wartime breakdown of slavery became apparent beyond those Southern districts actually penetrated by Union troops. In still-unoccupied parts of the Confederacy, masters, army officers, and government officials clashed repeatedly over which of them had the greater need for and claim to the labor of remaining slaves. This process eroded the real power of Rebel masters—and emboldened those still under their formal control. A South Carolina overseer bemoaned the “goodeal of obstanetry” he faced among “Some of the Peopl” working on his plantation, “mostly amongst the Woman a goodeal of Quarling and disputing and telling lies.” James Alcorn, a Mississippi planter, found that Union raids in his area had “thoroughly demoralized” his slaves. (This phrase was common planter parlance for saying that power over a slave—and a slave’s fear of a master—had faded.) That change, moaned Alcorn, had rendered his human property “no longer of any practical value.” Even among those field laborers who had not fled, a Louisiana overseer reported to his employer, “but very few are faithful—Some of those who remain are worse than those who have gone.” In one district after another, bondspeople began to call for improvements in their conditions as well as implicit but no less momentous alterations in their status—and they withheld their labor until such demands were met.… “Their condition is one of perfect anarchy and rebellion,” Georgia plantation mistress Mary Jones confided in her journal. “They have placed themselves in perfect antagonism to their owners and to all government and control. We dare not predict the end of all this.”49

The nature of slave resistance changed as well, with organizers shifting from the survival-orientated operations of the Underground Railroad to decisive military operations. Many former slaves worked with the Union forces, including Harriet Tubman, who worked as a scout and led raids and mass liberations of slaves.

The war also forced nonabolitionist northerners to confront the nature of slavery head-on. Writes Levine, “The wartime crisis of slavery left a deep imprint not only on southern whites but also on Union troops. As Lincoln and others had feared, and as the 1862 elections made clear, the decision to add the destruction of slavery to the North’s war aims at first provoked fierce opposition in parts of the Union. Few Union soldiers had gone to war committed to abolition … the Union soldier’s firsthand exposure to the real nature of slavery did much, however, to change minds and soften hearts.”50

When a destructive system is deeply entrenched, and when average people are isolated from the costs of that system, real change doesn’t come just from speeches. Real change happens—and only can happen—when that system is broken down by force. Then the oppressed gain the breathing room needed to fight back, and the apathetic can get their first look at that system’s real face.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 13, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

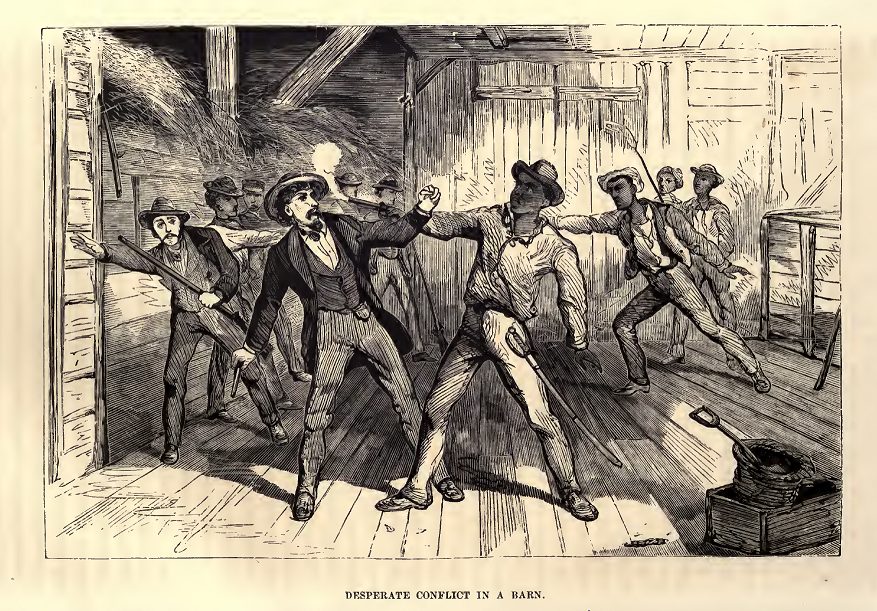

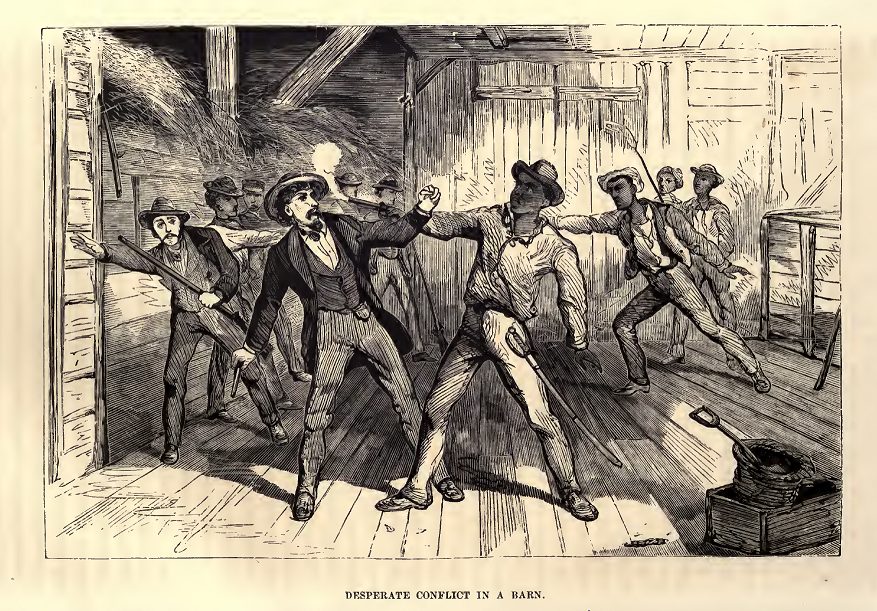

Featured image: Struggle for freedom in a Maryland barn. Engraving from William Still’s The Underground Rail Road

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

The Weather Underground was far from the only group that had difficulty implementing necessary tactics. The story of abolitionists prior to the Civil War gives us one of the best examples of this, in part because of the length and breadth of their struggle. Starting from a marginalized position in society, the struggle over slavery eventually inflamed an entire culture and provoked the bloodiest war in American history.

We’ll begin the story in the 1830s when several different currents of antislavery activism were growing rapidly. One of these currents was the Underground Railroad, run by both black and white people. Another current consisted of what you might call liberal abolitionists, predominantly white with a few black participants as well.

The general story of the Underground Railroad has become well-known, but there are many common misconceptions. Black slave escapes date back to the 1500s (when escapes south to Spanish Florida were rather more common), although some aspects of the nineteenth century Railroad were more systematically organized. One common but incorrect belief about the Underground Railroad is that it was run by magnanimous whites in order to aid black people otherwise unable to help themselves. In fact, this revisionist mythology is quite far from the truth.32 Until the 1840s, it was primarily run by and for black people who distrusted the involvement of whites. Escaped blacks were always in much greater danger than whites, and had to possess a great deal of skill, knowledge, and bravery in order to escape. The great majority of escapes were orchestrated by the slaves themselves, who spent months or years planning and reconnoitering escape routes and hiding places. Indeed, some historians have calculated that by the 1850s about 95 percent of escaping slaves were alone or with one or two companions.33

Furthermore, although the Underground Railroad is now recognized as a heroic and important part of the history of slave resistance, not all abolitionists of the time participated. In fact, some actually opposed the Underground Railroad. According to one history, “Abolitionists were divided over strategy and tactics, but they were very active and very visible. Many of them were part of the organized Underground Railroad that flourished between 1830 and 1861. Not all abolitionists favored aiding fugitive slaves, and some believed that money and energy should go to political action.”34

There’s no question that those who participated in the Underground Railroad were very brave, regardless of the color of their skin, and the importance of the Railroad to escaped slaves and their families cannot be overstated. The problem was that the Railroad just wasn’t enough to pose a threat to the institution of slavery itself. In 1830, there were around two million slaves in the United States. But at its peak, the Underground Railroad freed fewer than 2,000 slaves each year, less than one in one thousand. This escape rate was much lower than the rate of increase of the enslaved population through birth. Of course, many fugitive slaves worked to save money and buy their families out of slavery, which meant that the Railroad freed more people than just those who physically travelled it.

Tactical Development: From Moral Suasion to Political Confrontation35

While the Underground Railroad was growing in the 1830s, another antislavery current was growing as well. This one consisted mostly of white abolitionists, driven by Christian principles and a desire to convince slave owners to stop sinning and release their slaves. These early white Christian abolitionists recognized the horrors of slavery, but adopted an approach of pacifist moral exhortation. Historian James Brewer Stewart discusses their approach: “Calling this strategy ‘moral suasion,’ these neophyte abolitionists believed that theirs was a message of healing and reconciliation best delivered by Christian peacemakers, not by divisive insurgents.… They appealed directly to the (presumably) guilty and therefore receptive consciences of slaveholders with cries for immediate emancipation.” They believed, as liberals usually do, that the oppressive horrors perpetrated by those in power were mostly a misunderstanding (rather than an interlocking system of power that rewarded the oppressors for evil). So, of course, they believed that they could correct the mistake by politely arguing their case.

Stewart continues: “This would inspire masters to release their slaves voluntarily and thereby lead the nation into a redemptive new era of Christian reconciliation and moral harmony.… immediate abolitionists saw themselves as harmonizers, not insurgents, because the vast majority of them forswore violent resistance.… ‘Immediatists,’ in short, saw themselves not as resisting slavery by responding to it reactively, but instead as uprooting it by spiritually revolutionizing the corrupted values of its practitioners and supporters.” In other words, they fell prey to four of the strategic failings we’ve discussed so far. They didn’t use asymmetric strategic principles, largely because they weren’t using a resistance strategy at all. They were essentially lobbying, and their “morally superior” approach meant that, as a minority faction, they had no political force to bring to bear on those whom they lobbied. Furthermore, they were hopelessly naïve (or to state the problem more precisely, they were hopefully naïve) about the nature of power and the slave economy. As a result, they were unable to concoct a reasonable A to B strategy. Their so-called strategy, though well-meaning and moral, was more akin to a collective fantasy that overlooked the nature and extent of violence that slave culture would bring to bear on its adversaries.

Stewart recognizes this problem as well. “By adopting Christian pacifism and regarding themselves as revolutionary peacemakers, these earliest white immediatists woefully underestimated the power of the forces opposing them. Well before they launched their crusade, slavery had secured formidable dominance in the nation’s economy and political culture. To challenge so deeply entrenched and powerful an institution meant adopting postures of intransigence for which these abolitionists were, initially, wholly unprepared.”36

Need I spell out the parallels to our current situation? Pick any liberal or mainstream environmental or social justice movement. Mainstream environmentalism has been particularly naïve in this regard, largely ignoring the deeply entrenched nature of ecocidal activities in the capitalist economy, in industry, in daily life, and in the psychology of the civilized. Furthermore, mainstream environmentalists—who often do not come out of a long tradition of resistance—utterly ignore the force that those in power will bring to bear on any threat to that power. By assuming that society will adopt a sustainable way of life if only individual people can be persuaded, mainstream environmentalists ignore the rewards offered for unsustainability, and too often ignore those who pay the costs for such rewards.

Of course, mainstream environmentalism is hardly unique in this. Indeed, this basic trajectory is so common that it is nearly archetypal. Again and again, whenever privileged people have tried to ally themselves with oppressed people, we have seen this phenomenon at work. Seemingly ignorant of the daily violence perpetrated by the dominant culture, many people of privilege have wandered off into a strategic and tactical Neverland, which is based on their own personal wishes about how resistance ought to be, rather than a hard strategy that is designed to be effective and that draws on the experience of oppressed peoples and their long history of resistance. Sometimes the people of privilege listen and learn, and sometimes they don’t.

Of course, these early white abolitionists were on the right side, and, of course, their response to slavery was, morally speaking, far above that of the majority of white people’s. But, writes Stewart: “With the nation’s most powerful institutions so tightly aligned in support of slavery and white supremacy, it is clear that young white abolitionists were profoundly self-deceived when they characterized their work as ‘the destruction of error by the potency of truth—the overthrow of prejudice by the power of love—the abolition of slavery by the spirit of repentance.’ When so contending, they were deeply sincere and grievously wrong. To crusade for slavery’s rapid obliteration was, in truth, to stimulate not ‘the power of love’ and ‘repentance,’ but instead to promote the opposition of not only an overwhelming number of powerful enemies—the entire political system—but also the nation’s most potent economic interests—society’s most influential elites—and a popular political culture in the North that was more deeply suffused with racial bigotry than at previous times in the nation’s history.” This is a lesson we must remember.

They were highly optimistic about their chances. After increasing racial tensions and a series of violent uprisings in the early 1830s, one immediatist predicted that “the whole system of slavery will fall to pieces with a rapidity that will astonish.”37 This attitude is again reminiscent of the excess of hope we discussed earlier.

We should note that it was not just white abolitionists who were opposed to serious resistance at this stage, but some people of color as well. Historian Lois E. Horton writes that one black editor of a newspaper “penned an article addressed ‘To the Thoughtless part of our Colored Citizens,’ in which he admonished readers to act with more dignity and self-restraint when fugitive slaves were captured. [The editor] urged African Americans to leave the defense of fugitives to the lawyers … Public protest, even public assembly, [he] warned, would risk the loss of support from respectable allies. He was especially shocked by the involvement of Black women in this protest, singling them out for ‘everlasting shame’ and charging that they ‘degraded’ themselves by their participation.”38

But more militant abolitionists continued to gain prominence. Former fugitive slave Henry Highland Garnet rejected the pacifism of both white and black abolitionists, saying “There is not much hope of Redemption without the shedding of blood.”

Many white abolitionists retained their pacifist beliefs and practices, but as the abolition movement grew, it was increasingly perceived as a threat by slaveholders and those in power. An escalating wave of violent repression occurred, in which abolitionists and their allies were attacked, and their mailings and offices were burned. Many white abolitionists abandoned pacifism after white newspaper editor and abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy was gunned down in his office by proslavery thugs. William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of the foundational abolitionist paper the Liberator, wrote: “When we first unfurled the banner of the Liberator … we did not anticipate that, in order to protect southern slavery, the free states would voluntarily trample under foot all law and order, and government, or brand the advocates of universal liberty as incendiaries and outlaws.… It did not occur to us that almost every religious sect, and every political party would side with the oppressor.”39 Of course, they did not consider and dismiss the idea—it simply didn’t occur to them. This repression did, however, induce increasing numbers of Northerners to join with the abolitionists out of concern for the violations of law by the government and antiabolitionists.

The good news was that by the 1850s, more and more abolitionists were defying fugitive slave laws and even taking up arms to aid escaped slaves inside and outside of the Underground Railroad. Violent confrontations began to occur in a scattershot fashion or, to be more precise, defensive violence carried out by abolitionists became more common, since slavery had been based on violent confrontations since the beginning, and none of that was new to black people. It was soon not unheard of in the North for slaveholders or slave catchers to be shot—on one occasion in Boston in 1854, a crowd even stormed a courthouse where a fugitive slave was being held and overpowered the guards. Writes Stewart, “And even when physical violence did not result … oratorical militants increasingly urged their audiences to resort to physical destruction if more peaceable methods failed to stop federal slave catchers. On several occasions well-organized groups of abolitionists overwhelmed the marshals and spirited fugitives to safety. At other times they stored weapons, planned harassing manoeuvres, and massed as intimidating mobs.”40 Though only a decade earlier they were taking oaths never to use force, white abolitionists came to agree that use of lethal force against slave catchers, in self-defense, was morally justified. Armed defiance of slave catchers was a long tradition for black activists at that time, but a considerable change for white abolitionists. Many Christian abolitionists changed their tactics, arguing that not only was pacifism not required by God, but that it was a Christian’s duty and the “Law of God” to shoot a slave catcher.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 8, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Weather Underground, 1969

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

The key problem with identifying successful strategies is that the context of historical resistance is different from the present. Their goals were often different as well. There’s a difference between destroying or expelling a foreign power, and forcing a power to negotiate or offer concessions, and dismantling a domestic system of power or economics. Such differences are the reason we’ve used relatively few anticolonial movements as case studies; their context and strategy are too different.

Resistance groups often fall prey to several major strategic failures. We’ll discuss five big ones here:

- A failure to adhere to the principles of asymmetric struggle.

- A failure to devise a consistent strategy and goal.

- An inappropriate excess of hope; ignoring the scope of the problem.

- A failure to adequately negotiate the relationship between aboveground and underground operations.

- An unwillingness or inability to use the required tactics.

The first of these is a failure to adhere to the principles of asymmetric struggle. Yes, most resisters want to fight the good fight, and an out-and-out fight can be tempting. But that can only happen where resisters have superior forces on their side, which is almost never. The original IRA engaged in and lost pitched battles on more than one occasion.

In occupied Europe, writes M. R. D. Foot, “whenever there was a prospect that a large partisan force could be set up, people started asking for heavy weapons” instead of the submachine guns they were usually delivered. But artillery was always short on the front lines of conventional conflict, its presence drastically cut the mobility of a resistance group, and ammunition was hard to come by. “Bodies of resisters who clamoured for artillery were victims of the fallacy of the national redoubt … and of the old-fashioned idea that a soldier should stand and fight. The irregular soldier is usually much more use to his cause if he runs away, and fights in some other time and place of his own choosing.”16

Former Black Panthers have identified a similar problem with BPP strategy, specifically with their habit of equipping offices and houses to use as pseudofortresses. Explains Curtis Austin, “Using offices inside the ghetto as bases of operations was also a mistake. As a paramilitary organization, it should not have made defending clearly vulnerable offices a matter of policy. Sundiata Acoli echoed these sentiments when he noted this policy ‘sucked the BPP into taking the unwinnable position of making stationary defenses of BPP offices.… small military forces should never adopt as a general action the position of making stationary defences of offices, homes, buildings, etc.’ The frequency and quickness with which they were surrounded and attacked should have led them to develop a policy that would have allowed them to move from one headquarters to another with speed and stealth. Instead, the fledgling group constantly found itself defending sandbagged and otherwise well-fortified offices until their limited supplies of ammunition expired.”17

Early Weather Underground and SDS strategy similarly ignored the importance of surprise in planning actions by advertising and promoting open conflicts with the state and police in advance. This was criticized by other groups at the time. Writes Ron Jacobs, “From the Yippies’ vantage point, the idea of setting a date for a battle with the state was ridiculous: it provided the police with a greater capacity to counter-attack, and it also took away the element of surprise, the activists’ only advantage.… Pointing out the differences between the planned, offensive violence of Weatherman and Yippie’s spontaneous, defensive version, Abbie Hoffman termed Weatherman’s confrontations ‘Gandhian violence for the element of purging guilt through moral witness.’ ”18 (This analysis is interesting, if perhaps surprising and a little ironic, given the Yippies’ propensity for symbolic and theatrical actions.)

A most notable example of this problem was the “Days of Rage” gathering in Chicago in 1969. According to Weatherman John Jacobs, the intent of the Days of Rage was to confront the forces of the state and “shove the war down their dumb, fascist throats and show them, while we were at it, how much better we were than them, both tactically and strategically, as a people.”19 Jacobs told the Black Panthers that 25,000 protesters would be present.20 However, only about 200 showed up, met by more than a 1,000 trained and well-equipped police. In a speech the day of the event, Jacobs changed tack and argued for the importance of fighting for righteous and moral (rather than tactical or strategic) reasons: “We’ll probably lose people today … We don’t really have to win here … just the fact that we are willing to fight the police is a political victory.”21 The protesters then started something of a riot, smashing some police cars and luxury businesses, but also miscellaneous cars, a barbershop, and the windows of lower- and middle-class homes22—not a great argument for superior strategy and tactics. The police quickly dispatched the protesters with tear gas, batons, and bullets. In the following days, almost 300 people were arrested, including most of the Weather Underground and SDS leadership. The Black Panthers—who were not afraid of political violence or of fighting the police—denounced the action as foolish and counterproductive. The Weather Underground, at least, did seem to learn from this when they went underground and used tactics better suited to an asymmetric conflict. (How effective their tactics were while underground is another question.)

All of this brings us to the second common strategic problem of resistance groups. Although their drive and values may be laudable—and although their revolutionary commitment is not in question—many resistance groups have simply failed to devise a consistent strategy and goal. In order for a strategy to be verifiably feasible, it has to have an endpoint that can be described as well as a clear and reasonable path or steps that connect the implementation of the strategy to the endpoint.

Some people call this the “A to B” factor. Does a proposed strategy actually lay out a reasonable path between point A and point B? If you can’t explain how the strategy might work or how you can implement it, you certainly can’t evaluate the strategy effectively.

It seems dead obvious when put in these terms, but a real A to B strategy is often missing in resistance groups. The problems may seem so insurmountable, the risk of group schisms so concerning, that many movements just stagger along, driven by a deep desire for justice and in some cases a need to fight back. But this leads to short-term, small-scale thinking, and soon the resisters can’t see the strategic forest for the tactical trees.

This problem is not a new one. M. R. D. Foot describes it in his writings about resistance against the Nazis in Occupied Europe. “Less well-trained clandestines were more liable to lose sight of their goal in the turmoil of subversive work, and to pursue whatever was most easy to do, and obviously exasperating to the enemy, without making sure where that most easy course would lead them.”23

It’s good and courageous to want to fight injustice, but resisters who only fight back on a piecemeal basis without a long-term strategy will lose. Often the question of real strategy doesn’t even enter into discussion. Jeremy Varon wrote in his book on the Weather Underground and the German Red Army Faction that “1960s radicals were driven by an apocalyptic impulse resting on a chain of assumptions: that the existing order was thoroughly corrupt and had to be destroyed; that its destruction would give birth to something radically new and better; and that the transcendent nature of this leap rendered the future a largely blank or unrepresentable utopia.”24 Certainly they were correct that the existing order was (and still is) thoroughly corrupt and deeply destructive. The idea that destroying it would inevitably lead to something better by conventional human standards is more slippery. But the main problem is the profound gap in terms of their strategy and objective. They had virtually no plan beyond their choice of tactics which, in the case of the Weather Underground, became largely symbolic in nature despite their use of explosives. Their uncritical “apocalyptic” beliefs about the nature of revolution—something shared by many other militant groups—almost guaranteed that they would fail to develop an effective long-term strategy, a problem to which we’ll return later on.

It’s very interesting—and hopefully illuminating—that a group like the Weather Underground did so many things right but completely fell down strategically. We keep coming back to them and criticizing them not because their actions were necessarily wrong, but because they were on the right track in so many ways. The internal organization of the Weather Underground as a clandestine group was highly developed and effective, for example. And their desire to bring the war home, their commitment to action, far surpassed that of most leftists agitating against the Vietnam War.

But as Varon observed, “The optimism of American and West German radicals about revolution was based in part on their reading of events, which seemed to portend dramatic change. They debated revolutionary strategy, and their activism in a general way suggested the nature of the liberated society to come. But they never specified how turmoil would lead to radical change, how they would actually seize power, or how they would reorganize politics, culture, and the economy after a revolution. Instead, they mostly rode a strong sense of outrage and an unelaborated faith that chaos bred crisis, and that from crisis a new society would emerge. In this way, they translated their belief that revolution was politically and morally necessary into the mistaken sense that revolution was therefore likely or even inevitable.”25

All of this brings us to a third common flaw in resistance strategy—an excess of hope. Obviously, we now know that a 1960s American revolution was far from inevitable. So why did the Weather Underground and others believe that it was? To some degree, this sort of anchorless optimism is a coping mechanism. Resistance groups are up against powerful foes, and believing that your desired victory is somehow inevitable can help morale. It can also be wrong. We should remember former prisoner of war James Stockdale’s “very important lesson”: “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”26

Another factor is what you might call the bubble or silo effect. People tend to self-sort into groups of people they have something in common with. This can lead to activists being surrounded by people with similar beliefs, and even becoming socially isolated from those who don’t share their ideas. Eventually, groupthink occurs, and people start to believe that far more people share their perspective than actually do. It’s only a short step to feeling that vast change is imminent. This is especially true if the goal is nebulous and difficult to evaluate.

The false belief that “the revolution is nigh” is hardly limited to ’60s or leftist groups, of course. Even World War II German dissidents like Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, a conservative but anti-Nazi politician, fell prey to the same misapprehension. Writes Allen Dulles: “Despite Goerdeler’s realization of the Nazi peril, he greatly overestimated the strength of the relatively feeble forces in Germany which were opposing it. Optimistic by temperament, he was often led to believe that plans were realities, that good intentions were hard facts. As a revolutionary he was possibly naïve in putting too much confidence in the ability of others to act.”27

Significantly, but perhaps not surprisingly, his naïveté extended not just to potential resisters but even to Hitler. Prior to the July 20 plot, he firmly believed that if only he could sit down and meet with Hitler, he could rationally convince him to admit the error of his ways and to resign. His friends were barely able to stop him from trying on more than one occasion, which would have obviously been foolish and dangerous to the resistance because of their planned assassination.28 Of course, Nazi Germany was not just a big misunderstanding, and after the failed putsch, Goerdeler was arrested, tortured for months by the Gestapo, and then executed.

The fourth common strategic flaw is a failure to adequately negotiate the relationship between aboveground and underground operations. We touched on this on a number of occasions in the organization section. Many groups—notably the Black Panthers—failed to implement an adequate firewall between the aboveground and underground. But we aren’t just talking about organizational partitions and separation; the history of resistance has showed again and again the larger strategic challenge of coordinating cooperative aboveground and underground action.

This has a lot to do with building mutual support and solidarity. The Weather Undeground in its early years was notably abysmal at this. Their attitude and rhetoric was aggressively militant. The organization, in the words of its own members (written after the fact), had a “tendency to consider only bombings or picking up the gun as revolutionary, with the glorification of the heavier the better,” an attitude which even alienated other armed revolutionary organizations like the BPP.29 Indeed, the Weather Underground would deliberately seek confrontation for the sake of confrontation even with people with whom it professed alignment. For example, in one action during the Vietnam War, Weather Underground members went to a working-class beach in Boston and erected a Vietcong flag, knowing that many on the beach had family in the US armed forces. When encircled, instead of discussing the war, they aggressively ratcheted up the tension, idealistically believing that after a brawl both sides could head over to the bar for a serious chat. Instead, the Weather Underground got their asses kicked.30

Now, there’s something to be said for pushing the limits of “legitimate” resistance. There’s something to be said for giving hesitant resisters a kick in the pants—or at least a good example—when they should be doing better. But that’s not what the Weather Underground did. In part the problem was their lack of a clear and articulable strategy. In his memoir, anarchist Michael Albert relates a story about being asked to attend an early Weather Underground action so that he could see what they do. “About ten of us, or thereabouts, piled into a subway car heading for the stop nearest a large dorm at Boston University. While in the subway, trundling along underground, one of the Weathermen, according to prearranged agreement, stood up on his seat to give a speech to his captive audience of other subway riders. He nervously yelled out ‘Country Sucks, Kick Ass,’ and promptly sat down. That was their entire case. It was their whole damn enchilada.”31 What are people supposed to get from that? By contrast, no one reading the Black Panther Party’s Ten Point Plan would be confused about their strategy and goals.

But the Weather Underground’s most ineffective actions in the aboveground vs. underground department were those that actually harmed aboveground organizations. Their actions in Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) are a prime example. SDS was a broad-based organization with wide support, which focused on participatory democracy, direct action, and nonviolent civil disobedience for civil rights and against the war. Before the formation of the Weather Underground, a group called the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM), led by Bernardine Dohrn, later a leader of the Weather Underground, essentially hijacked SDS. They gained power at a 1969 national SDS convention and expelled members of a rival faction (the Progressive Labor Party and Worker Student Alliance). They hoped to push the entire organization into more militant action, but their coup caused a split in the organization, which rapidly disintegrated in the following years. In the decades since, no leftist student organization has managed to even approach the scale of SDS.

The bottom line is that RYM took a highly functional aboveground group and destroyed it. The Weather Underground’s exaltation of militancy got in the way of radical change and caused a permanent setback in popular leftist organizing. What the Weather Underground members failed to realize is that not everyone is going to participate in underground or armed resistance, and that everyone does not need to participate in those things. The civil rights and antiwar movements were appropriate places for actionists to try to build nonviolent mass movements, where very important work was being done, and SDS was a crucial group doing that work. Aboveground and underground groups need each other, and they must work in tandem, both organizationally and strategically. It’s a major strategic error for any faction—aboveground or underground—to dismiss the other half of their movement. To arrogantly destroy a functioning organization is even worse.

There is a fifth common strategic failure, which in some ways is the most important of them all: the unwillingness or inability to apply appropriate tactics to carry out the strategy. Is your resistance movement using its entire tool chest? A resistance movement that is fighting to win considers every operation and every tactic it can possibly employ. That doesn’t mean that it actually uses every tool or tactic. But nothing is simply dismissed without consideration.

The Weather Underground, to return again to their example, was a group which began with an earnest desire to fight back, to “bring the war home,” and express genuine solidarity with the people of Vietnam and other countries under American attack by taking up arms. Initially, this was meant to include attacks on human beings in key positions in the military-industrial complex. Indeed, before they went underground, as we’ve already discussed, the Weather Underground was eager to attack even low-level representatives of the state hierarchy, specifically police. Shortly after going underground, they changed their strategy.

The turning point in the Weather Underground’s strategy of violence versus nonviolence was the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion. In the spring of 1970, an underground cell there was building bombs in preparation for a planned attack on a social event for noncommissioned officers at a nearby army base. However, a bomb detonated prematurely in the basement, killing three people, injuring two others (who fled), and destroying the house. After the explosion, the Weather Underground took what you could call a nonviolent approach to bombings—they attacked symbols of power like the Pentagon and the Capitol building, but went out of their way to case the scenes before detonation to ensure that there were no human casualties.

Rather ironically, their post–Greenwich Village tactical approach again became largely symbolic and nonviolent, much like the aboveground groups they criticized. Lacking connections to other movements and organizations, and lacking a clear strategic goal, the Weather Underground’s efforts were doomed to be ineffective.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 4, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Introduction to Strategy” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Aric McBay

There’s one nagging thought that always returns to me when I’m studying WWII resistance strategy: resisters in Occupied Europe were brave, even heroic, but their actions alone did not bring down the Nazis. Resisters weakened the Nazis, hampered their actions, disrupted their logistics, and destroyed materiel. But they lacked the resources and organization to decisively engage and defeat Hitler’s forces. It took a conventional military assault by the Allies to finish the job. And the overwhelming majority of this was done by the Russians, with their large army relying heavily on infantry tactics. We can speculate about whether guerrilla uprisings in occupied countries would have eventually developed and ended Nazi rule, but that’s not what happened during the actual years of occupation.

For those of us who want to stop this culture from killing the planet, there are no capital “A” Allies with vast resources and armies. That’s the nature of our predicament. We may be able to ally ourselves with powers of lesser evil, the way that Spanish Anarchists allied themselves with Spanish Republicans and Soviets in Spain, or the way antebellum abolitionists allied themselves with Union Republicans against the Confederate South. But that will only get us so far, and joining the lesser evil can be dangerous.

How, then, would a successful resistance movement expand its actions beyond resistance that merely hampers to that which decisively dismantles civilization’s centralized systems of power, those that are allowing it to steal from the poor and destroy the planet? We’ll return to this in the Core Strategy chapter, but there are three main answers in terms of any theoretical deep green resistance movement’s “allies.” One is that the depletion of finite resources, along with the dead-ending of that pyramid scheme called industrial capitalism, will provoke a cascading industrial and economic collapse. Indeed, just during the time we’ve been writing this book, we’ve seen a banking crisis turn into a major credit crisis, which has cascaded into a recession and simmering global economic crisis. That disruption will undermine the ability of those in power to exercise their influence and concentrate wealth, and generally throw industrial civilization into a state of disarray.

A second answer is ecological and climate collapse. Cheap oil has so far insulated urban industrial people from most effects of increasing and catastrophic damage to the biosphere. But industrial collapse will mean the end of that insulation, and will mean that thousands of years of civilization’s “ecological debt” will come due. Furthermore, the earth is not just a passive battlefield—it’s alive, and it’s fighting on the side of the living.

A third, more tentative answer is that as all of this transpires, less overtly militant aboveground forces may fight against those in power out of self-interest. Once those in power no longer have the “energy slaves” offered by cheap oil and industry, they will (once again) increasingly try to extract that labor from human beings, from literal slaves. Hopefully people in the minority world, where the rich and powerful minority live, will have the good sense to see that and fight back against this enslavement, as so many people in the majority world, where the impoverished minority live, have already been doing for so long. But this is a more tenuous proposition. Popular resentment may be quick to build against a particular head of state or particular political party. Developing a mass culture of resistance against an entire economic or political system, however, can take decades. People who are privileged and entitled take a long time to change, if they change at all. More likely they will side with someone who makes big but ultimately empty promises.