by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 6, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the eleventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

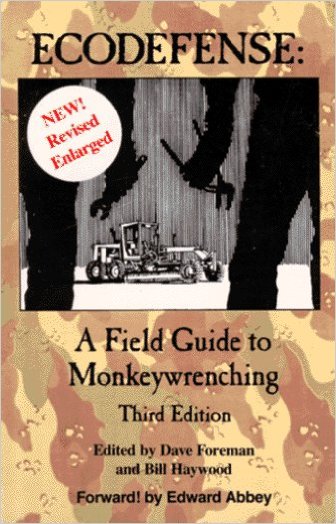

Deep Green Resistance advocates for the sabotage of infrastructure. Some nonviolent advocates discuss the use of sabotage in relation to nonviolence.

In The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp does not classify the sabotage of property as violent, but states that sabotage could become violent if it causes injury or death. He considers that certain actions (including removal of key components, vehicle fuel, records or files) can fall somewhere between sabotage and nonviolent action. He describes that when nonviolent action has not been successful, sabotage has sometimes followed. Sharp does not describe any instances of sabotage being used by a disciplined nonviolent movement. In his view, sabotage is more closely related to violence than nonviolence, in terms of principles, strategy, and mechanisms of operation. [1]

Sharp also lists nine reasons why sabotage will seriously weaken a nonviolent movement:

- it risks unintentional physical injury;

- it may result in the use of “violence” or the use of force against those who discover plans of sabotage;

- it requires secrecy in planning and carrying out missions, which also may result in “violence” or the use of force if discovered;

- it only requires a few resisters, which reduces large scale participation;

- it demonstrates a lack of confidence in nonviolent actions;

- it relies on physical destruction rather than people challenging each other directly;

- sabotage and nonviolence are rooted in very different strategies—nonviolence in withdrawal of consent, sabotage in destroying property;

- if any physical injury or death happens, even if by accident, it will result in a loss of support for the nonviolent cause;

- sabotage may cause increased repression. [2]

Ackerman and Kruegler agree with Sharp and recommend avoiding sabotage and demolition, but they do identify “nonviolent sabotage” as a form of economic subversion that renders resources for repression inoperative by removing components, overloading systems and jamming electronics. [3]

Branagan differentiates nonviolent property damage and sabotage. Property damage that occurs during a nonviolent action may involve, for example, a hole in the road that has minimum impact, especially compared to ecological, structural, cultural or physical violence. In his model, sabotage is defined by conducting sustained systematic attacks on property, and then getting away with it. [4]

Bill Meyers describes that sabotage was the primary tactics used by Earth First! in the US in 1989. However, during this period nonviolence activists joined the group, arguing that sabotage is a form of violence that feeds a cycle by giving those sabotaged the excuse for their own violence. They also conflated property destruction with violence against persons. Meyers explains that by 1990, this shift in participants’ ideological stances regarding violence resulted in the transition of Earth First! from a revolutionary group that was a genuine threat to the corporations destroying the earth into a much less physically threatening group.

Bill Meyers describes that sabotage was the primary tactics used by Earth First! in the US in 1989. However, during this period nonviolence activists joined the group, arguing that sabotage is a form of violence that feeds a cycle by giving those sabotaged the excuse for their own violence. They also conflated property destruction with violence against persons. Meyers explains that by 1990, this shift in participants’ ideological stances regarding violence resulted in the transition of Earth First! from a revolutionary group that was a genuine threat to the corporations destroying the earth into a much less physically threatening group.

To conclude this run of articles, over the last seven posts I’ve attempted to: define nonviolence and pacifism; explain what nonviolent resistance is; describe its advantages; signpost you to where you can learn more about struggles and who is advocating for nonviolent resistance; and finally how nonviolence and sabotage fit together.

Pacifism is clearly based on good intentions and an understandable desire for a world at peace. Nonviolent resistance is a very important tactic in our struggle. But crucially, it can not be the only tactic if the movement for environmental and social justice ever hopes to be effective. If the planet is to remain livable in the medium term then the movement needs to determine which tactics are most likely to succeed. Regardless of the differences of opinion and focus within the movement, the movement as well as the planet are losing. Being wedded to mostly nonviolent tactics is a major cause of this failure.

Strategic nonviolence has an important part to play in our resistance but the need for some nonviolent advocates to only advocate pacifism or nonviolent resistance in any circumstances and try to mandate it across whole movements, is counterproductive and causing the movement to be less effective.

An act of sabotage or property destruction is violent or nonviolent depending on the intentions and the way they are carried out (see post 4). I don’t think that sabotage or property destruction of nonliving things such as buildings, vehicles, and infrastructure in the defence of life can ever be considered violent.

In the next run of posts I will explore the problems with nonviolence and pacifism.

This is the eleventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp, 1973, page 608/9

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, page 609/10

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century, Peter Ackerman and Chris Kruegler, 1993, page 39

- Global Warming: Militarism and Nonviolence,The Art of Active Resistance, Marty Branagan, 2013, page 124

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 28, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the tenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

The aim of this post is to inform those interested in researching how to strategically confront the state using nonviolent direct action or force; and how this information might be applied to their situation.

Two books describe and analyse a number of struggles. In Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, [1] Ackerman and Kruegler analyse a number of nonviolent conflicts based on their Twelve Principles of Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, which I described in a previous post. The conflicts include: the First Russian Revolution 1904-1906; Ruhrkampf regional defense against occupation, 1923; the Indian Independence Movement, 1930-1931; Denmark occupation and resistance, 1940-1945; El Salvador civic strike, 1944; Resistance against the Polish Communist Party, 1980-1981.

In The Failure of Nonviolence, [2] Gelderloos describes and analyses over thirty nonviolent and militant struggles, which have occurred since the end of the cold war. He uses a four point criteria: whether a movement seized space for new social relations; whether it spread an awareness of new ideas (and secondarily if this awareness was passive or whether it inspired others to fight); whether it had elite support; whether it achieved any concrete gains in improving people’s lives.

The struggles he lists are: The Oka Crisis, The Zapatistas, The Pro-Democracy Movement in Indonesia, The Second Intifada, The Black Spring in Kabylie, The Corralito (in Argentina), the Day the World Said No to War, The Colour Revolution, Kuwait’s “Blue Revolution” and Lebanon’s “Cedar Revolution,” The 2005 Banlieue Uprisings, Bolivia’s Water War and Gas War, Kyrgyzstan’s Tulip Revolution, The Oaxaca Rebellion, The 2006 CPE Protests, 2007 Saffron Revolution, The 2008 insurrection in Greece, Bersih Rallies, Guadeloupe General Strike, UK Student Movement, Tunisian Revolution, The Egyptian Revolution of 2011, The Libyan Civil War, The Syrian Civil War, 15M Movement and General Strikes, 2001 United Kingdom Anti-Austerity Protests, 2011 England riots, Occupy, The 2011-2013 Chile student protests, The Quebec Student Movement, and The Mapuche struggle.

The Global Nonviolent Action Database is also an online resources with some 1,000 examples of nonviolent actions.

Gelderloos also offers a very comprehensive list of those individuals advocating for pacifism and nonviolence. [3] Other organizations active in this realm include: the Albert Einstein Institution; the International Centre on Nonviolent Conflict, the Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies, Waging Nonviolence and Campaign Nonviolence.

The Radical Think Tank in London has been researching the ways in which nonviolent direct action could be used in the UK. Its members have identified three key mechanisms to enhance political participation and mobilisation to increase the campaign’s likelihood of success: (1) the conditional commitment or pledges; (2) dilemma actions, a lose-lose situation for the authorities; and (3) fostering open space, where people can talk freely about what’s bothering them, which is empowering and motivates them to act. They have also mapped out a number of hypothetical campaign progressions which combine all three mechanisms in order to show how much more effective they can be when combined.

This is the tenth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century, Peter Ackerman and Chris Kruegler, 1993

- Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 48-97

- Failure of Nonviolence, page 160-215

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 17, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the eighth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Srdja Popovic, one of the organisers of Otpor, the nonviolent group that challenged Slobodon Milosevic in Serbia, now offers nonviolence training through the The Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS). Popovic views a nonviolent campaign as a war, but one which is fought with different kinds of weapons or sanctions. [1] He argues that a successful nonviolent struggle requires nonviolent discipline, unity, and planning. [2] He points out that the state employs fear and the threat of arrest or more terrifying repercussions to make the people obey:

All oppression relies on fear in order to be effective…the ultimate point of all this fear is not merely to make you afraid. A dictator isn’t interested in running a haunted house. Instead, he wants to make you obey. And when it comes down to it, whether or not you obey is always your choice. Let’s say that you wake up in some nightmare scenario out of a mafia movie, where some wacko tries to force you to dig a ditch. They put a gun to your head and threaten to kill you if you don’t start shoveling. Now, they certainly have the power to scare you, and it’s certainly not easy to argue with someone who has a pistol pointed right at your temple. But can anybody really make you do something? Nope. Only you can decide whether or not to dig that ditch. You are totally free to say no. The punishment will certainly be severe, but it’s still your choice to decline. And, if you absolutely refuse to pick up that shovel and they shoot you dead, you still haven’t dug them a ditch. So the point of oppression and fear isn’t to force you to do something against your will – which is impossible – but rather to make you obey. That’s where they get you. [3]

Popovic then explains that once those involved with Otpor moved past the fear of the unknown—and of being arrested—they were able to blunt the state’s oppressive power:

The best way to overcome the fear of the unknown is with knowledge. From the earliest days of Otpor!, one of the most effective tools the police had against us was the threat of arrest. Notice I didn’t say arrest but just the threat of it. The threat was much more effective than the thing itself, because before we actually started getting arrested by Milošević’s police, we didn’t know what jails were like, and because people are normally much more afraid of the unknown, we imagined Milošević’s prisons to be the worst kind of hell…But then when things started getting heated, a lot of us actually were arrested, and when we got back we told the others all about it. We left out none of the details. We wrote down and shared with our fellow revolutionaries every bit of what had happened in the jails. We wanted those about to get arrested themselves – we knew there were bound to be many, many more of us picked up by the dictator’s goons – to understand every step of what was going to happen to them. [4]

While this reasoning may not be appropriate in all socio-political contexts (such as for survivors of rape, assault, domestic abuse, and hate crime), it’s useful as a real world example of the power of knowledge in organizing a movement.

He explains that in order for the average citizen to really engage with an issue, they need to believe something to be unfair or wrong. [5] Like Sharp, Popovic believes that “in a nonviolent struggle, the only weapon that you’re going to have is numbers.” [6] Nonviolent struggles try to win by converting people to the cause. Following this reasoning, Popovic advocates that a nonviolent campaign be relatable to arouse the sympathy of the masses. [7]

Author Tim Gee writes in Counterpower: Making Change Happen, that power is “the ability for A to get B to do something that B would not otherwise have done,” and that “if the interests of those in power are not threatened…the likelihood of rulers voluntarily giving up power altogether is small.” [8] Gee proposes a strategic approach he calls “counterpower, which turns traditional notions of power on their head. Counterpower is the ability of B to remove the power of A.”

The concept of counterpower involves challenging accepted truths or refusing to obey. Economic counterpower can be exercised through strikes and boycotts. Physical counterpower can mean fighting back or nonviolently utilizing human bodies to disrupt, stall, or permanently end the perpetration of injustices. [9] Gee goes on to describe four stages to a successful campaign: consciousness, coordination, confrontation, and consolidation. [10]

Mike Ryan makes the astute observation in Pacifism as Pathology that writers from the 1800s did not state that nonviolence means the “absolute, constant and permanent absence of force or violence.” Doug Man’s “The Movement” and Pat James’ “Physical Resistance to Attack: The Pacifist’s Dilemma, the Feminist’s Hope” argue that it’s important to use the least forceful response that is appropriate to that situation, rather than not using force under any circumstances.

If Man’s and James’ view on the acceptable level of violence were adopted by nonviolence movements today, then the ideological distance between nonviolent resisters and advocates of violent resistance would stem more from differences in analysis and choice of tactics, rather than the current focus on what’s moral or strategic. [11]

This is the eighth installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men, and Other Non-Violent Techniques to Galvanise Communities, Overthrow Dictators, or Simply Change the World, Srdja Popovic, Matthew Miller, 2015, page 88

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 213

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 130

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 131

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 143

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp, 1973, page 52

- Blueprint for Revolution, page 204

- Counterpower Why Movements Succeed and Fail, Gee, Tim, 2011, page 200

- Counterpower, page 13

- Counterpower, page 130

- Pacifism as Pathology, Ward Churchill, 1998, page 136

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 14, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the seventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Lierre Keith, author of Deep Green Resistance, has very clear views on

using nonviolent direct action. These views have been strongly influenced by Gene Sharp’s work. She states that the first question activists must answer is whether the political system they seek to change needs to be adjusted inside a basically sound institutional framework, or whether it requires more fundamental change. If the political system requires fundamental change, such change cannot be achieved by compromise or persuasion; it necessitates some kind of struggle that inherently involves conflict. Those who believe such institutions to be sound will “keep banging their head[s] against these institutions but the institutions will not yield to their fundamental principles.”

Keith points out that neither engagement in a struggle nor the use of force necessitates violence. At this stage the question of whether to use force or nonviolent tactics is premature; decisions about tactics come later.

Keith is critical of the liberal notion of consent, as she does not consider consent to be freely given. Consent is extracted from the ruled either ideologically or by terror and force. Therefore, the whole function of power is to extract consent. In Keith’s view, consent is actually a euphemism for submission. She explains how most of us don’t want to be forced to consent or submit, we want to be fully informed people who have actual choices to control the material conditions of our lives. We do not want to be given choices within such limited conditions; we want to actually control the conditions, so that our choices are choices in a meaningful sense. Keith states that, as a group, we can choose to remove our consent from the systems of power or not. If it is agreed that we wish to remove our consent, the question becomes: how best to do that? How best to get people to understand that they can remove their consent, and then, how to organise that withdrawal so the systems crumble?

Keith describes how nonviolent direct action impinges on the state’s power more directly than using force, because their power comes from the population. For Keith this is the important insight into why this technique works. When the population takes back their political, economic, and social power from the state then “the state is left with nothing.” Withdrawing power does not work if just done emotionally, and that this is where many on the left have gone wrong.

Another important point Keith makes is that nonviolent resistance to power makes visible the repression and structural violence of the system. Therefore, for a nonviolent campaign to work, those involved must maintain nonviolent discipline. Keith explains that such commitment is crucial to the success of this strategy because it reveals the violent overreaction of those in power. If the movement reacts with force, it will look like a riot to those observing (or those sitting on the sidelines trying to work out which side to join), and it will be difficult to distinguish between the violence of the state and the self-defense of the activists. Such a situation demonstrates how a diversity of tactics can be problematic – it can cause the movement to be viewed negatively and therefore make it less effective. Diversity of tactics does have a part to play in our struggle, but timing is important. I will discuss this topic more in a future post.

Keith is clear that verbally appealing to or begging the powerful for some kind of conciliation is not nonviolent direct action; it is a verbal appeal or a conciliatory effort. She states that these actions do not actually confront power but are merely a rational or emotional appeal. Nonviolent direct action doesn’t work because it is morally or spiritually superior, it works because it:

- exposes the violence of the state and demystifies power

- breaks through the psychology of the oppressed

- ultimately removes the support on which the powerful depend

Keith concludes that nonviolent direct action can work, but when determining our tactics we must always ask these key questions: is it going to work for the struggle we are in? Do we have enough people and time? It takes a lot of people and time to learn from the mistakes of initially using nonviolent direct action to get to a point when a movement can use it effectively. [1]

In Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, Ackerman and Kruegler argue that having a strategy and applying it properly are the most important factors determining the outcome of a nonviolent conflict.

They define strategy in this overarching sense as “a process by which one analyses a given conflict and determines how to gain objectives at minimum expense and risk.” [2] They also explain that “strategic performance is likely to be a significant, possibly the dominant, factor in the outcome of nonviolent struggle.” [3]

Ackerman and Kruegler also state the need to distinguish between policy, strategy, and tactics when addressing a conflict. Within this framework, “policy” consists of the objectives that define an acceptable outcome, and will therefore determine when the activists stop fighting. Strategy, in this more focused sense, is the plan for achieving the objectives, which may need to adapt to the group circumstances. Tactical decisions are related to how to initiate or respond to interactions with the opponent. [4] Ackerman and Kruegler identify twelve principles of strategic nonviolent conflict. [5]

Twelve Principles of Strategic Nonviolent Conflict

Principles of Development

1. Formulate functional objectives.

2. Develop organizational strength.

3. Secure access to critical material resources.

4. Cultivate external assistance.

5. Expand the repertoire of sanctions.

Principles of Engagement

6. Attack the opponent’s strategy for consolidating control.

7. Mute the impact of the opponents’ violent weapons.

8. Alienate opponents from expected bases of support.

9. Maintain nonviolent discipline.

Principles of Conception

10. Assess events and options in light of levels of strategic

decision making.

11. Adjust offensive and defensive operations according to the relative vulnerabilities of the protagonists.

12. Sustain continuity between sanctions, mechanisms, and objectives.

This is the seventh installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G2gRtXp3qp8

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century, Peter Ackerman and Chris Kruegler, 1993, page 6

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, page 2

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, page 7

- Strategic Nonviolent Conflict, page 21 and read online

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 8, 2016 | Human Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis

by Alex Jensen / Local Futures

In 2015, a major study of 24 indicators of human activity and environmental decline titled “The Great Acceleration” concluded that, “The last 60 years have without doubt seen the most profound transformation of the human relationship with the natural world in the history of humankind”.[1] We have all seen aspects of these trends, but to look at the study’s 24 graphs together is to apprehend, at a glance, the totality of the monstrous scale and speed of modern economic activity. According to lead author W. Steffen, “It is difficult to overestimate the scale and speed of change. In a single lifetime humanity has become a planetary-scale geological force.”[2]

Every indicator of intensity and scale of economic activity — from global trade and investment to water and fertilizer use, from pollution of every sort to destruction of environments and biodiversity — has shot up, precipitously, beginning around 1950. The graphs for every such trend point skyward still.

The Great Acceleration is manifest everywhere, including many areas not covered in the study. It is impossible to directly, humanly appreciate the ghastly scale of change. Only statistics can do that. For example:

- Humans now extract and move more physical material than all natural processes combined. Global material extraction has grown by more than 90 percent over the past 30 years, reaching almost 70 billion tons today.[3]

- In this century “global economic output expanded roughly 20-fold, resulting in a jump in demand for different resources of anywhere between 600 and 2,000 percent”.[4]

- For more than 50 years, global production of plastic has continued to rise.[5] Today, around 300 million tons of plastic are produced globally each year. “About two thirds of this is for packaging; globally, this translates to 170 million tons of plastic largely created to be disposed of after one use.”[6]

- The global sale of packaged foods has jumped more than 90 percent over the last decade, with 2012 sales topping $2.2 trillion.[7]

- “In the last 50 years, a staggering 140 million hectares… has been taken over by four industrial crops: soya bean, oil palm, rapeseed and sugar cane. These crops don’t feed people. They are grown to feed the agro-industrial complex.”[8]

Not only are the scale and speed of materials extraction, production, consumption and waste ballooning, but so too the scale and pace of the movement of materials through global trade. For instance, trade volumes in physical terms have increased by a factor of 2.5 over the past 30 years. In 2009, 2.3 billion tons of raw materials and products were traded around the globe.[9] Maritime traffic on the world’s oceans has increased four-fold over the past 20 years, causing more water, air and noise pollution on the open seas.[10]

Not only are the scale and speed of materials extraction, production, consumption and waste ballooning, but so too the scale and pace of the movement of materials through global trade. For instance, trade volumes in physical terms have increased by a factor of 2.5 over the past 30 years. In 2009, 2.3 billion tons of raw materials and products were traded around the globe.[9] Maritime traffic on the world’s oceans has increased four-fold over the past 20 years, causing more water, air and noise pollution on the open seas.[10]

While it may be correct, generically, to ascribe all these signs of the Great Acceleration to “humanity” or “human activity” as a whole, this ascription is also flawed. Indeed, the study concludes that the global economic system in particular has been a primary driver of the Great Acceleration. The graphs of economic activity (such as the amount of foreign direct investment or the number of McDonald’s restaurants) and environmental decline (such as biodiversity loss, forest loss, percentage of fisheries “fully exploited,” etc.) look identical from a distance — both shooting dizzyingly upward since 1950. The resemblance is not coincidental. The latter are a consequence of the former.

This expansion of global economic activity has been driven forward by the dynamics of capitalism and the pursuit of endless profits: by marketing and advertising; by subsidies and sops to industry of every stripe; and by the concomitant destruction of local, self-reliant communities around the world. In the process, much of “humanity” has been swept into the jetsam of the overall economic system. While this system may be the product of some human designs, to confuse it with humanity at large is to get the story backward.

One incontrovertible conclusion of all this, it seems to me, is that it is precisely the increasing scale of economic activity – of “the economy” – that is the heart of the multiple interlocking crises that beset societies and the earth today. The relentlessly expansionist logic of the system is inimical to life, to the world, even to genuine well-being. If we wish to instead honor, defend, and respect life and the world, we must upend that logic, and begin the urgent task of down-scaling economic activity and the system that drives it. We must embark upon the “Great Deceleration.”

Nevertheless, from every organ of the establishment, where the commercial mind reigns, we hear that the challenge before us is not deceleration, but making the great acceleration even greater by ramping up production and consumption still further. Even as governments expound solemnly on the need to arrest climate change and promote Sustainable Development Goals, they are handing over nearly boundless subsidies to industry, pushing for the expansion of global trade, and otherwise facilitating the acceleration of the acceleration.

Projections based on the assumption that the great acceleration will continue ad infinitum show, for example, that the number of cars will nearly double from 1.1 billion today, to 2 billion by 2040; that seaborne trade will increase from 54 to 286 trillion ton-miles; that global GDP will climb from $69 trillion to $164 trillion; and so on. As a news article reporting the projections declares, “If there’s a common theme, it’s that there’s going to be more of everything in the years ahead”.[11] By 2025, the output of solid waste is expected to grow 70 percent, from 3.5 to more than 6 million tons per day.[12] Leaving aside the actual feasibility of such growth – given biophysical limits that are already well-surpassed – the very fact that the political and economic establishment takes such growth for granted and will continue to pursue it heedlessly is cause for grave concern.

In India, chemical and physical pollution occasioned by the frenzied rush of industrial development has become so treacherous that it is deforming air and water into poisons to be avoided at the risk of health and life itself. Mephitic mountains of plastic waste choke every town and city, clog drains, suffocate rivers and shores, fill the stomachs of animals. Pesticides have killed soil and farmers alike across the country. Despite these and so many other manifestations of ecocide, industry and the government — central and state-level alike — clamor for more of it, faster. Because it is a ‘developing’ country, we are told, the average Indian vastly underconsumes plastic, energy, cars, et al. Cultural traditions of thrift and sharing, wherever they still hang on, are seen as nettlesome but surmountable barriers to keeping the growth machine growing, faster. Replacing each and every one of those traditional practices with packaged, often disposable, commodities is an explicit goal of industry. Relentlessly generating novel needs is another. The current government’s “Make In India” program, marketed to attract foreign investors and businesses, is the latest campaign to fuel this process.[13]

In India, chemical and physical pollution occasioned by the frenzied rush of industrial development has become so treacherous that it is deforming air and water into poisons to be avoided at the risk of health and life itself. Mephitic mountains of plastic waste choke every town and city, clog drains, suffocate rivers and shores, fill the stomachs of animals. Pesticides have killed soil and farmers alike across the country. Despite these and so many other manifestations of ecocide, industry and the government — central and state-level alike — clamor for more of it, faster. Because it is a ‘developing’ country, we are told, the average Indian vastly underconsumes plastic, energy, cars, et al. Cultural traditions of thrift and sharing, wherever they still hang on, are seen as nettlesome but surmountable barriers to keeping the growth machine growing, faster. Replacing each and every one of those traditional practices with packaged, often disposable, commodities is an explicit goal of industry. Relentlessly generating novel needs is another. The current government’s “Make In India” program, marketed to attract foreign investors and businesses, is the latest campaign to fuel this process.[13]

No matter how polluting, how much land and water are required, how many communities will be displaced and livelihoods destroyed, the formula is basically the same: more mines, more coal and power plants, more tourism. More and more of everything. For every industry, every product, every process that has swelled to become a planetary-scale abscess, the normal prescription that should obtain — “stop the swelling!” — is inverted. The out-of-control global economic system needs more and more growth just to feed and maintain itself.

In defense of this system one may hear some version of the refrain: “These are the unfortunate costs we must pay to alleviate poverty, improve human well-being, and provide enough for all.” This argument has become embarrassingly spurious. It is now widely known that not only has the great up-scaling bequeathed the planet and its inhabitants a legacy of destruction, ugliness, and waste, but its prodigious production and profit has failed to make a dent in the hunger and privation suffered by hundreds of millions. At the same time, it has unleashed a storm of junk food and diet-related diseases across the planet, which has persecuted the poor the worst. The menacing pollution attendant to the great acceleration also harms the poor the worst. It exacerbates poverty even as it churns the planet into money. Meanwhile, those most enriched in the process amount to a conference-room-sized group of individuals. The statistics will likely have grown even more outlandish by the time this is read: the world’s 62 richest people own as much wealth as the poorest half of humanity.[14]

This system of plunder and inequality has, unsurprisingly, left in its wake demoralized human souls. The great acceleration and loneliness, depression, anxiety and estrangement are two sides of the same sinister coin; paralyzed and tyrannized by a surfeit of superficial ‘choice’, by loss of meaning and connection, even the supposed beneficiaries of this system have been made miserable by it.[15]

So the increasing scale and speed of the economy is, for the vast majority, the enemy of prosperity. This fact offers some hope, for reducing the scale and speed of the economy provides the possibility of relief and reclamation of contentment for those afflicted by affluence, while at the same time providing not “growth” — which the poor have never and will never be able to eat — but the actual material needs that are being trampled beneath the very stampede of growth that is supposed to deliver those needs. The great up-scaling is a sybaritic saturnalia for an infinitesimally small and incomprehensibly moneyed elite. It is everyone else’s curse.

Downscaling the economy, therefore, is not only necessary to save and perhaps enable regeneration of our beleaguered earthly home; it is also a genuinely humane, anti-poverty agenda. This may sound counter-intuitive to those marinading in trickle-down theory.

Upsetting the great acceleration juggernaut will require innumerable, profound systemic shifts. Since the regnant system is not the consequence but rather the cause of consumerism, acquisitiveness, separation, alienation, etc., it will require first and foremost resistance to the forces that relentlessly propagate it — stopping corporate plunder of all sorts (from mines to minds); stopping and revoking neoliberal ‘free trade’ agreements; breaking up and dismantling corporate-state power and the legal frameworks that underpin it; and, challenging the fundamentalist logic of unlimited growth. It will simultaneously require the (re)construction of radical alternative systems, rooted in environmental ethics, ecological integrity, social justice, decentralization and deep democracy, beauty, simplicity, cooperation, sharing, slowness, and a constellation of related eco-social-ethical values.

But where will the motive to act either in resistance or in regeneration come from, if the values of commercialized growth societies — competition, individualism, narcissism, nihilism, avarice — are so deeply indoctrinated? How can the opposite values be resuscitated after decades or centuries of anesthetization and repression? The fact is that all over the world, there has always been and continues to be tremendous push-back against the system, along with nurturance of countless alternatives. This is testament not only to human resilience and common sense, but to the utter asynchrony of this system with the genuine well-being of people.

To acknowledge and celebrate this spirited and widespread push-back is not to be complacent or naïve about the terrifying hegemony and momentum of the great acceleration. It is, rather, precisely to disrupt the complacency and debilitation of “inevitablism.”

Thankfully, all over the world, vibrant movements of resistance-(re)construction both new and ancient are saying loudly, “we are ready to stop being trickled-down upon.” The Degrowth movement is assailing the status quo assumption of a cozy positive relationship between economic growth and well-being and even (weirdly) environmental “improvement.” Its many exponents and activists are broadcasting the reality of the obvious-to-all-but-economists inverse relationship between growth and well-being. Given that the economy today is vastly exceeding what the planet and its denizens can give and take, degrowth — as its name announces — promotes not merely slowing and stopping growth, but reversing it.

At centers like Can Decreix on the Mediterranean coast, the main argument of degrowth – that well-being improves and life becomes richer through sufficiency, commoning and technological-material downscaling – is practiced, demonstrated and shared. Human muscle and craft skill reclaim from machines simple, pleasurable subsistence work, done communally. Heat energy of the sun is used to bake bread and warm water. Music and fun become not something that must purchased on weekends, but part of the fabric of everyday. But it is not merely an escapist, “live your values while the world burns” sort of experiment; on the contrary, its members are deeply involved in the broader political struggles (e.g. against “free trade” treaties) that are a necessary corollary to living alternatively.

There are also many sister concepts and movements to degrowth, that, despite their differences, share some basic, fundamental values and perspectives. There is Buen Vivir/Sumak Kawsay emerging out of indigenous, eco-centric Andean cosmovisions, calling not for alternative development but alternatives to development, for affirmation and strengthening of traditional practices, knowledge systems, processes and relationships (human and non-human alike) that since time immemorial have embodied many of the qualities that movements (like degrowth) in industrialized locales are striving to re-create.[16]

There are also many sister concepts and movements to degrowth, that, despite their differences, share some basic, fundamental values and perspectives. There is Buen Vivir/Sumak Kawsay emerging out of indigenous, eco-centric Andean cosmovisions, calling not for alternative development but alternatives to development, for affirmation and strengthening of traditional practices, knowledge systems, processes and relationships (human and non-human alike) that since time immemorial have embodied many of the qualities that movements (like degrowth) in industrialized locales are striving to re-create.[16]

On the Andean altiplano, most Aymara and Quechua farming families still nurture, process and eat a spectacular varietal diversity of tubers, grains, legumes and other foods. One farmer I stayed with near Lake Titicaca grew 109 varieties of potato, plus dozens more of oca, olluco, mashua, quinoa, edible lupine, fava, wheat, barley, maize, and much more. He and his family, like the majority of other farming families there, provide most of their own milk, cheese, meat and wool from livestock like cows, alpacas, goats and sheep. They live in houses fashioned from adobe bricks of local clay, roofed with local grass thatch. Their young children know dozens of wild medicinal plants. They do all this not as heroic, isolated survivalists, but in webs of community and earthly relationships of community, mutual aid, sharing and care. These communities have met their needs through local-regional economies – many based in barter – for centuries.[17] Are they thus perfect and free of all troubles? Of course not. But many of their worst troubles are imposed by capitalist industrialism and other forces of “progress.”

Perhaps the signal movement synthesizing resistance and (re)construction, ancient and contemporary, South and North, is the food sovereignty movement. This movement turns on its head 500 years of colonialist food policy, which would have everyone give up their food autonomy and diverse traditions and have peasants moved off the land into cities to become factory proletarians or, if remaining in the countryside, to become plantation proletarians exporting food calories, water and labor power – receiving in exchange paltry wages with which to shop for packaged “food-like stuff” in a global agribusiness supermarket. The movement inveighs against the political-economic forces that continue the war against peasants and subsistence economies, and demonstrates again and again the superiority (health, nutrition, productivity, ecological, social) of diverse, small, localized, cooperatively-worked, integrated polycultures of the sort that characterized food systems before the logic of the factory was imposed onto the land.[18]

These and many other movements are pointing the way back from the abyss into which the great acceleration has hurled us, directing us towards the Great Deceleration necessary to live again with affection and beauty on this earth.

This essay originally appeared in In Praise of Downscaling: 21st Century Conversations on How Small is Still Beautiful.

Photo credits: Indian trash heap: Juan del Rio; Andes grain winnowing: Alex Jensen.

Endnotes:

[1] Steffen, W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O., and Ludwig, C. (2015) ‘The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration’, The Anthropocene Review, 16 January. http://anr.sagepub.com/content/early/2015/01/08/2053019614564785.abstract.

[2] http://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2015-01-15-new-planetary-dashboard-shows-increasing-human-impact.html

[3] Giljum, S., Dittrich, M., Lieber, M., and Lutter, S. (2014) ‘Global Patterns of Material Flows and their Socio-Economic and Environmental Implications: A MFA Study on All Countries World-Wide from 1980 to 2009’, Resources 3, 319-339. www.mdpi.com/2079-9276/3/1/319/pdf.

[4] Dobbs, R., Oppenheim, J., Thompson, F., Brinkman, M., and Zornes, M. (2011) ‘Resource Revolution: Meeting the world’s energy, materials, food, and water needs’, McKinsey Global Institute.

[5] Worldwatch, 2015.

[6] Jowit, J. (2011) ‘Global hunger for plastic packaging leaves waste solution a long way off’, The Guardian, 29 December.http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/dec/29/plastic-packaging-waste-solution.

[7] Norris, J. (2013) ‘Make Them Eat Cake: How America is Exporting Its Obesity Epidemic’, Foreign Policy, 3 September. http://foreignpolicy.com/2013/09/03/make-them-eat-cake/.

[8] GRAIN (2014) ‘Hungry for Land: Small farmers feed the world with less than a quarter of all farmland’, GRAIN 28 May. http://www.grain.org/article/entries/4929-hungry-for-land-small-farmers-feed-the-world-with-less-than-a-quarter-of-all-farmland

[9] Giljum, S. et al, op. cit.

[10] American Geophysical Union (2014) ‘Worldwide ship traffic up 300 percent since 1992’, ScienceDaily, 17 November. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/11/141117130826.htm.

[11] Scutt, D. (2016) ‘This chart shows an insane forecast for worldwide growth of ships, cars, and people’, Business Insider Australia, 19 April.http://www.businessinsider.com.au/global-crude-oil-demand-emerging-markets-india-china-april-bernstein-2016-4.

[12] Hoornweg, D., and Bhada-Tata, P. (2012) ‘What a waste? A global review of solid waste management’, Urban development series knowledge papers; no. 15, Washington, DC: World Bank Group.http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/302341468126264791/What-a-waste-a-global-review-of-solid-waste-management.

[13] Make In India

[14] Oxfam (2016) ‘An economy for the 1%’, Oxfam Briefing Paper 210, 18 January.https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/bp210-economy-one-percent-tax-havens-180116-en_0.pdf.

[15] Monbiot, G. (2013) ‘One Rolex Short of Contentment’, The Guardian, 10 December. http://www.monbiot.com/2013/12/09/one-rolex-short-of-contentment/.

[16] Gudynas, E. (2011) ‘Buen Vivir: Today’s Tomorrow’, Development 54(4).http://www.gudynas.com/publicaciones/GudynasBuenVivirTomorrowDevelopment11.pdf.

[17] cf. Marti, N. and Pimbert, M. (2006) ‘Barter Markets: Sustaining people and nature in the Andes’, IIED. http://pubs.iied.org/14518IIED/, and Argumedo, A. and Pimbert, M. (2010) ‘Bypassing Globalization: Barter markets as a new indigenous economy in Peru’, Development 53(3). http://link.springer.com/article/10.1057%2Fdev.2010.43.

[18] Fitzgerald, D. (2003) Every Farm a Factory: The Industrial Ideal in American Agriculture, New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

Bill Meyers describes that sabotage was the primary tactics used by Earth First! in the US in 1989. However, during this period nonviolence activists joined the group, arguing that sabotage is a form of violence that feeds a cycle by giving those sabotaged the excuse for their own violence. They also conflated property destruction with violence against persons. Meyers explains that by 1990, this shift in participants’ ideological stances regarding violence resulted in the transition of Earth First! from a revolutionary group that was a genuine threat to the corporations destroying the earth into a much less physically threatening group.

Bill Meyers describes that sabotage was the primary tactics used by Earth First! in the US in 1989. However, during this period nonviolence activists joined the group, arguing that sabotage is a form of violence that feeds a cycle by giving those sabotaged the excuse for their own violence. They also conflated property destruction with violence against persons. Meyers explains that by 1990, this shift in participants’ ideological stances regarding violence resulted in the transition of Earth First! from a revolutionary group that was a genuine threat to the corporations destroying the earth into a much less physically threatening group.