by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 26, 2012 | Climate Change, Obstruction & Occupation

By Candice Bernd / TruthOut

The deadline for the review of TransCanada’s permits for the Gulf Coast portion of the Keystone XL pipeline was Monday, June 25, 2012. At the Texas Army Corp of Engineers Galveston office and without any finalization of review, those permits will be automatically granted to the corporation – thanks to President Obama’s announcement that he would expedite the southern leg of the pipeline in Cushing, Oklahoma, back in March.

That’s why Texas climate justice activists, including myself, are officially announcing the Tar Sands Blockade, an epic action that we have been organizing since the beginning of the year. We’re mostly associated with Rising Tide North Texas, and we’re 100 percent prepared to use nonviolent, direct action to block the pipeline’s construction to protect our home.

Bring it, TransCanada

The Tar Sands Blockade will be coordinating nonviolent, direct actions along the pipeline route to stop this zombie pipeline once and for all. We are working with national allies as well as local communities to coordinate a road show that will travel throughout Texas and Oklahoma as well as a regional training effort for activists interested in getting involved in the blockade movement against the Keystone XL.

“Our action is giving a new meaning to ‘Don’t Mess with Texas,'” said Tar Sands Blockade Collective member Benjamin Kessler. Kessler is also a member of Iraq Veterans Against the War.

The permits for the pipeline’s construction are being automatically granted under the Nationwide Permit 12 protocol, or NWP 12. The permits do not need an environmental impact statement to accompany them, according to this process. That very fact alone endangers more than 631 streams and wetlands that the pipeline will cross in our state. Not only that, but the entire Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer, which supplies drinking water for ten to 12 million homes across 60 counties in East Texas, along the pipeline’s path, is threatened with contamination.

The Keystone XL remains key to the expansion of the Alberta tar sands and leading NASA climate scientist James Hansen has called the pipeline “a fuse to the largest carbon bomb on the planet.” According to Hansen, if the carbon stored in the tar sands is released into the atmosphere, it would mean “game over for the climate.”

350.org founder Bill McKibben has worked hard to get Hansen’s message out to the public and to lawmakers in Washington. After more than 1,200 were arrested during the onset of the Tar Sands Action last fall, another 12,000 turned out to surround the White House to tell President Obama that the Keystone XL is not in the nation’s best interest.

McKibben was elated to hear that the Tar Sands Blockade is continuing to foster the spirit of resistance against the pipeline in the South with the use of nonviolent, direct action.

“Let’s be clear what the drama is here: human bodies and spirits up against the unlimited cash and political influence of the fossil fuel industry. We all should be grateful for this peaceful witness,” McKibben said.

Landowners living along the pipeline’s path say they have been intimidated by TransCanada to sign away the rights to their land, and it’s not just landowners that will lose. The pipeline is expected to destroy indigenous archeological and historical sites – including grave sites – in Oklahoma and Texas.

Read more from TruthOut: http://truth-out.org/news/item/9997-its-time-for-a-texas-tar-sands-blockade

by DGR News Service | Jan 8, 2024 | ANALYSIS, Alienation & Mental Health, Human Supremacy, Listening to the Land, Movement Building & Support

Editor’s Note: The Earth wants to live. And she wants us to stop destroying her. It is a simple answer, but one with many complex processes. How do we get there? Shall I leave my attachments with the industrial world and being off-the-grid living, like we were supposed to? Will that help Earth?

Yes, we need to leave this way of life and live more sustainably. But what the Earth needs is more than that. It is not one person who should give up on this industrial way of life, rather it is the entire industrial civilization that should stop existing. This requires a massive cultural shift from this globalized culture to a more localized one. In this article, Katie Singer explores the harms of this globalized system and a need to shift to a more local one. You can find her at katiesinger@substack.com

What Does the Earth Want From Us?

By Katie Singer/Substack

Last Fall, I took an online course with the philosopher Bayo Akomolafe to explore creativity and reverence while we collapse. He called the course We Will Dance with Mountains, and I loved it. I loved the warm welcome and libations given by elders at each meeting’s start. I loved discussing juicy questions with people from different continents in the breakout rooms. I loved the phenomenal music, the celebration of differently-abled thinking, the idea of Blackness as a creative way of being. When people shared tears about the 75+-year-old Palestinian-Israeli conflict, I felt humanly connected.

By engaging about 500 mountain dancers from a half dozen continents, the ten-session course displayed technology’s wonders.

I could not delete my awareness that online conferencing starts with a global super-factory that ravages the Earth. It extracts petroleum coke from places like the Tar Sands to smelt quartz gravel for every computer’s silicon transistors. It uses fossil fuels to power smelters and refineries. It takes water from farmers to make transistors electrically conductive. Its copper and nickel mining generates toxic tailings. Its ships (that transport computers’ raw materials to assembly plants and final products to consumers) guzzle ocean-polluting bunker fuel.

Doing anything online requires access networks that consume energy during manufacturing and operation. Wireless ones transmit electro-magnetic radiation 24/7.

More than a decade before AI put data demands on steroids, Greenpeace calculated that if data storage centers were a country, they’d rank fifth in use of energy.

Then, dumpsites (in Africa, in India) fill with dead-and-hazardous computers and batteries. To buy schooling, children scour them for copper wires.

Bayo says, “in order to find your way, you must lose it.”

Call me lost. I want to reduce my digital footprint.

A local dancer volunteered to organize an in-person meeting for New Mexicans. She invited us to consider the question, “What does the land want from me?”

Such a worthwhile question.

It stymied me.

I’ve lived in New Mexico 33 years. When new technologies like wireless Internet access in schools, 5G cell sites on public rights-of-way, smart meters or an 800-acre solar facility with 39 flammable batteries (each 40 feet long), I’ve advocated for professional engineering due diligence to ensure fire safety, traffic safety and reduced impacts to wildlife and public health. I’ve attended more judicial hearings, city council meetings and state public regulatory cases and written more letters to the editor than I can count.

In nearly every case, my efforts have failed. I’ve seen the National Environmental Protection Act disregarded. I’ve seen Section 704 of the 1996 Telecom Act applied. (It prohibits legislators faced with a permit application for transmitting cellular antennas from considering the antennas’ environmental or public health impacts.) Corporate aims have prevailed. New tech has gone up.

What does this land want from me?

The late ecological economist Herman Daly said, “Don’t take from the Earth faster than it can replenish; don’t waste faster than it can absorb.” Alas, it’s not possible to email, watch a video, drive a car, run a fridge—or attend an online conference—and abide by these principles. While we ravage the Earth for unsustainable technologies, we also lose know-how about growing and preserving food, communicating, educating, providing health care, banking and traveling with limited electricity and web access. (Given what solar PVs, industrial wind, batteries and e-vehicles take from the Earth to manufacture, operate and discard, we cannot rightly call them sustainable.)

What does the land want from me?

If I want accurate answers to this question, I need first to know what I take from the land. Because my tools are made with internationally-mined-and-processed materials, I need to know what they demand not just from New Mexico, but also from the Democratic Republic of Congo, from Chile, China, the Tar Sands, the deep sea and the sky.

Once soil or water or living creatures have PFAS in them, for example, the chemicals will stay there forever. Once a child has been buried alive while mining for cobalt, they’re dead. Once corporations mine lithium in an ecosystem that took thousands of years to form, on land with sacred burial grounds, it cannot be restored.

One hundred years ago, Rudolf Steiner observed that because flicking a switch can light a room (and the wiring remains invisible), people would eventually lose the need to think.

Indeed, technologies have outpaced our awareness of how they’re made and how they work. Technologies have outpaced our regulations for safety, environmental health and public health.

Calling for awareness of tech’s consequences—and calling for limits—have become unwelcome.

In the last session of We Will Dance with Mountains, a host invited us to share what we’d not had a chance to discuss. AI put me in a breakout room with another New Mexican. I said that we’ve not discussed how our online conferences ravage the Earth. I said that I don’t know how to share this info creatively or playfully. I want to transition—not toward online living and “renewables” (a marketing term for goods that use fossil fuels, water and plenty of mining for their manufacture and operation and discard)—but toward local food, local health care, local school curricula, local banking, local manufacturing, local community.

I also don’t want to lose my international connections.

Bayo Akomolafe says he’s learning to live “with confusion and make do with partial answers.”

My New Mexican friend aptly called what I know a burden. When he encouraged me to say more, I wrote this piece.

What does the land want from us? Does the Earth want federal agencies to create and monitor regulations that decrease our digital footprint? Does the Earth want users aware of the petroleum coke, wood, nickel, tin, gold, copper and water that every computer requires—or does it want these things invisible?

Does the Earth want us to decrease mining, manufacturing, consumption—and dependence on international corporations? Does it want children to dream that we live in a world with no limits—or to learn how to limit web access?

Popular reports from 2023

Telecommunications

“A longer-lasting Internet starts with knowing our region’s mineral deposits”

“Digital enlightenment: an invitation”

“Calming Behavior in Children with Autism and ADHD”

Solar PVs

“Call Me a Nimby” (a response to Bill McKibben’s Santa Fe talk)

“Do I report what I’ve learned about solar PVs—or live with it, privately?”

E-vehicles

“Transportation within our means: initiating the conversation overdue”

“Who’s in charge of EV chargers—and other power grid additions?”

“When Land I Love Holds Lithium: Max Wilbert on Thacker Pass, Nevada”

Photo by Noah Buscher on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Jun 16, 2023 | Colonialism & Conquest, Mining & Drilling, NEWS, Obstruction & Occupation, Repression at Home

Editor’s Note: The following are two press releases by Ox Sam Camp. As communities get more radical against corporations, corporations use their power against them. This is not the first time that this has happened and it will not be the last. As activists, it is necessary for us to understand the risk associated with any action against the system. The earlier we understand this, the better we can strategize.

The article is followed by a short reflection piece by Elisabeth Robson on the need for the environmental movement to put our allegiance with the natural world, as is demonstrated in this fight to protect Thacker Pass.

Ox Sam Camp Raided by Police at Thacker Pass

One Arrested as Prayer Tipis Are Dismantled and Ceremonial Items Confiscated

6/8/23

Contact: Ox Sam Camp

OxSam.org

THACKER PASS, NV — On Wednesday morning, the Humboldt County Sheriff’s department on behalf of Lithium Nevada Corporation, raided the Ox Sam Newe Momokonee Nokutun (Ox Sam Indigenous Women’s Camp), destroying the two ceremonial tipi lodges, mishandling and confiscating ceremonial instruments and objects, and extinguishing the sacred fire that has been lit since May 11th when the Paiute/Shoshone Grandma-led prayer action began.

One arrest took place on Wednesday at the direction of Lithium Nevada security. During breakfast, law enforcement arrived. Almost immediately without warning, a young Diné female water protector was singled out by Lithium Nevada security and arrested, not given the option to leave the camp. Two non-natives were allowed to “move” in order to avoid arrest. The Diné woman was quickly handcuffed and subsequently loaded into a sheriff’s SUV for transport to Winnemucca for processing.

While on the highway, again without warning or explanation, she was transferred into a windowless, pitch-black holding box in the back of a pickup truck. “I was really scared for my life,” the woman said. “I didn’t know where I was or where I was going. I know that MMIW is a real thing, and I didn’t want to be the next one.” She was transported to Humboldt County Jail, where she was charged with criminal trespass and resisting arrest, then released on bail.

Just hours before the raid, Ox Sam water protectors could be seen for the second time this week bravely standing in the way of large excavation equipment and shutting down construction at the base of Sentinel Rock.

To many Paiute and Shoshone, Sentinel Rock is a “center of the universe,” integral to many Nevada Tribes’ way of life and ceremony, as well as a site for traditional medicines, tools, and food supply for thousands of years. Thacker Pass is also the site of two massacres of Paiute and Shoshone people. The remains of the massacred ancestors have remained unidentified and unburied since 1865, and are now being bulldozed and crushed by Lithium Nevada for the mineral known as “the new white gold.”

Since May 11th, despite numerous requests by Lithium Nevada workers, the Humboldt County Sheriff Department has been reticent and even unwilling to arrest members of the prayer camp, even after issuing three warnings for blocking Pole Creek Road access to Lithium Nevada workers and sub-contractors, while allowing the public to pass through.

“We absolutely respect your guys’ right to peacefully protest,” explained Humboldt County Sheriff Sean Wilkin on May 12th. “We have zero issues with [the tipi] whatsoever… We respect your right to be out here.”

On March 19th the Sheriff arrived again, serving individual fourteen-day Temporary Protection Orders against several individuals at camp. The protection orders were granted by the Humboldt County Court on behalf of Lithium Nevada based on sworn statements loaded with misrepresentations, false claims, and, according to those targeted, outright false accusations by their employees. Still, Ox Sam Camp continued for another week. The tipis, the sacred fire, and the prayers remained unchallenged for a total of twenty-seven days of ceremony and resistance.

The scene at Thacker Pass this week looked like Standing Rock, Line 3, or Oak Flat. As Lithium Nevada’s workers and heavy equipment tried to bulldoze and trench their way through the ceremonial grounds surrounding the tipi at Sentinel Rock, the water protectors put their bodies in the way of the destruction, forcing work stoppage on two occasions.

Lithium Nevada’s ownership and control of Thacker Pass only exists because of the flawed permitting and questionable administrative approvals issued by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). BLM officials have refused to acknowledge that Peehee Mu’huh is a sacred site to regional Tribal Nations and have continued to downplay and question the significance of the double massacre through two years of court battles.

Three tribes — the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, Summit Lake Paiute Tribe, and Burns Paiute Tribe — remain locked in litigation with the Federal Government, challenging the BLM’s permit process from the beginning. The tribes filed their latest response to the BLM’s Motion to Dismiss on Monday. BLM is part of the Department of the Interior, which is led by Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo).

On Wednesday, at least five Sheriff’s vehicles, several Lithium Nevada worker vehicles, and two security trucks arrived at the original tipi site that contained the ceremonial fire, immediately adjacent to Pole Creek Road. The one native water protector was arrested without warning, while others were issued with trespass warnings and allowed to leave the area. Once the main camp was secured, law enforcement then moved up to secure and dismantle the tipi site at Sentinel Rock, a mile away.

There is a proper way to take down a tipi and ceremonial camp, and then there is the way Humboldt County Sheriffs proceeded on behalf of Lithium Nevada Corporation. Tipis were knocked down, tipi poles were snapped, and ceremonial objects and instruments were rummaged through, mishandled, and impounded. Empty tents were approached and secured in classic SWAT-raid fashion. One car was towed. As is often the case when lost profits lead to government assaults on peaceful water protectors, Lithium Nevada Corporation and the Humboldt County Sheriffs have begun to claim that the raid was done for the safety of the camp members and for public health.

Josephine Dick (Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone), who is a descendent of Ox Sam and one of the matriarchs of Ox Sam Newe Momokonee Nokutun, made the following statement in response to the raid:

“As Vice Chair of the Native American Indian Church of the State of Nevada, and as a Paiute-Shoshone Tribal Nation elder and member, I am requesting the immediate access to and release of my ceremonial instruments and objects, including my Eagle Feathers and staff which have held the prayers of my ancestors and now those of Ox Sam camp since the beginning. There was also a ceremonial hand drum and medicines such as cedar and tobacco, which are protected by the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

In addition, my understanding is that Humboldt County Sherriff Department along with Lithium Nevada security desecrated two ceremonial tipi lodges, which include canvasses, poles, and ropes. The Ox Sam Newe Momokonee Nokutun has been conducting prayers and ceremony in these tipis, also protected by the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. When our ceremonial belongings are brought together around the sacred fire, this is our Church. Our Native American Church is a sacred ceremony. I am demanding the immediate access to our prayer site at Peehee Mu’huh and the return of our confiscated ceremonial objects.

The desecration that Humboldt County Sherriffs and Lithium Nevada conducted by knocking the tipis down and rummaging through sacred objects is equivalent to destroying a bible, breaking The Cross, knocking down a cathedral, disrespecting the sacrament, and denying deacons and pastors access to their places of worship. It is in direct violation of my American Indian Religious Freedom rights. This violation of access to our ceremonial church and the ground on which it sits is a violation of Presidential Executive Order 13007.

The location of the tipi lodge that was pushed over and destroyed is at the base of Sentinel Rock, a place our Paiute-Shoshone have been praying since time immemorial. After two years of our people explaining that Peehee Mu’huh is sacred, BLM Winnemucca finally acknowledged that Thacker Pass is a Traditional Cultural District, but they are still allowing it to be destroyed.”

Josephine and others plan to make a statement on live stream outside the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office in Winnemucca on the afternoon of Friday, June 9th around 1pm.

Another spiritual leader on the front lines has been Dean Barlese from the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe. Despite being confined to a wheelchair, Barlese led prayers at the site on April 25th which led to Lithium Nevada shutting down construction for a day, and returned on May 11th to pray over the new sacred fire as Ox Sam camp was established.

“This is not a protest, it’s a prayer,” said Barlese. “But they’re still scared of me. They’re scared of all of us elders, because they know we’re right and they’re wrong.”

Land Defenders Arrested, Camp Raided After Blocking Excavator

First arrests are underway and camp is being raided after land defenders halted an excavator this morning at Thacker Pass.

6/7/23

OROVADA, NV — This morning, a group of Native American water protectors and allies used their bodies to non-violently block construction of the controversial Thacker Pass lithium mine in Nevada, turning back bulldozers and heavy equipment.

The dramatic scene unfolded this morning as workers attempting to dig trenches near Sentinel Rock were turned back by land defenders who ran and put their bodies between heavy equipment and the land.

Now they are being arrested and camp is being raided.

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone people consider Thacker Pass to be sacred. So when they learned that the area was slated to become the biggest open-pit lithium mine in North America, they filed lawsuits, organized rallies, spoke at regulatory hearings, and organized in the community. But despite all efforts over the last three years, construction of the mine began in March.

That’s what led Native American elders, friends and family, water protectors, and their allies to establish what they call a “prayer camp and ceremonial fire” at Thacker Pass on May 11th, when they setup a tipi at dawn blocking construction of a water pipeline for the mine. A second tipi was erected several days later two miles east, where Lithium Nevada’s construction is defacing Sentinel Rock, one of their most important sacred sites.

Sentinel Rock is integral to many Nevada Tribes’ worldview and ceremony. The area was the site of two massacres of Paiute and Shoshone people. The first was an inter-tribal conflict that gave the area it’s Paiute name: Peehee Mu’huh, or rotten moon. The second was a surprise attack by the US Cavalry on September 12th, 1865, during which the US Army slaughtered dozens. One of the only survivors of the attack was a man named Ox Sam. It is some of Ox Sam’s descendants, the Grandmas, that formed Ox Sam Newe Momokonee Nokotun (Indigenous Women’s Camp) to protect this sacred land for the unborn, to honor and protect the remains of their ancestors, and to conduct ceremonies. Water protectors have been on-site in prayer for nearly a month.

On Monday, Lithium Nevada Corporation also attempted to breach the space occupied by the water protectors. As workers maneuvered trenching equipment into a valley between the two tipis, water protectors approached the attempted work site and peacefully forced workers and their excavator to back up and leave the area. According to one anonymous land defender, Lithium Nevada’s action was “an attempted show of force to fully do away with our tipi and prayer camp around Sentinel Rock.”

Ranchers, recreationists, and members of the public have been allowed to pass without incident and water protectors maintain friendly relationships with locals. Opposition to the mine is widespread in the area, and despite repeated warnings from the local Sheriff, there have been no arrests. Four people, including Dorece Sam Antonio of the Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone Tribe (an Ox sam descendant) and Max Wilbert of Protect Thacker Pass, have been targeted by court orders barring them from the area. They await a court hearing in Humboldt County Justice Court.

“Lithium Nevada is fencing around the sacred site Sentinel Rock to disrupt our access and yesterday was an escalation to justify removal of our peaceful prayer camps,” said one anonymous water protector at Ox Sam Camp. “Lithium Nevada intends to desecrate and bulldoze the remains of the ancestors here. We are calling out to all water protectors, land defenders, attorneys, human rights experts, and representatives of Tribal Nations to come and stand with us.”

“I’m being threatened with arrest for protecting the graves of my ancestors,” says Dorece Sam Antonio. “My great-great Grandfather Ox Sam was one of the survivors of the 1865 Thacker Pass massacre that took place here. His family was killed right here as they ran away from the U.S. Army. They were never buried. They’re still here. And now these bulldozers are tearing up this place.”

Another spiritual leader on the front lines has been Dean Barlese, a spiritual leader from the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe. Despite being confined to a wheelchair, Barlese led prayers at the site on April 25th (shutting down construction for a day) and returned on May 11th.

“I’m asking people to come to Peehee Mu’huh,” Barlese said. “We need more prayerful people. I’m here because I have connections to these places. My great-great-great grandfathers fought and shed blood in these lands. We’re defending the sacred. Water is sacred. Without water, there is no life. And one day, you’ll find out you can’t eat money.”

The 1865 Thacker Pass massacre is well documented in historical sources, books, newspapers, and oral histories. Despite the evidence but unsurprisingly, the Federal Government has not protected Thacker Pass or even slowed construction of the mine to allow for consultation to take place with Tribes. In late February, the Federal Government recognized tribal arguments that Thacker Pass is a “Traditional Cultural District” eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. But that didn’t stop construction from commencing.

“This is not a protest, it’s a prayer,” said Barlese. “But they’re still scared of me. They’re scared of all of us elders, because they know we’re right and they’re wrong.”

For more, go to Ox Sam Camp.

Hug Trees Not Pylons

By Elizabeth Robson

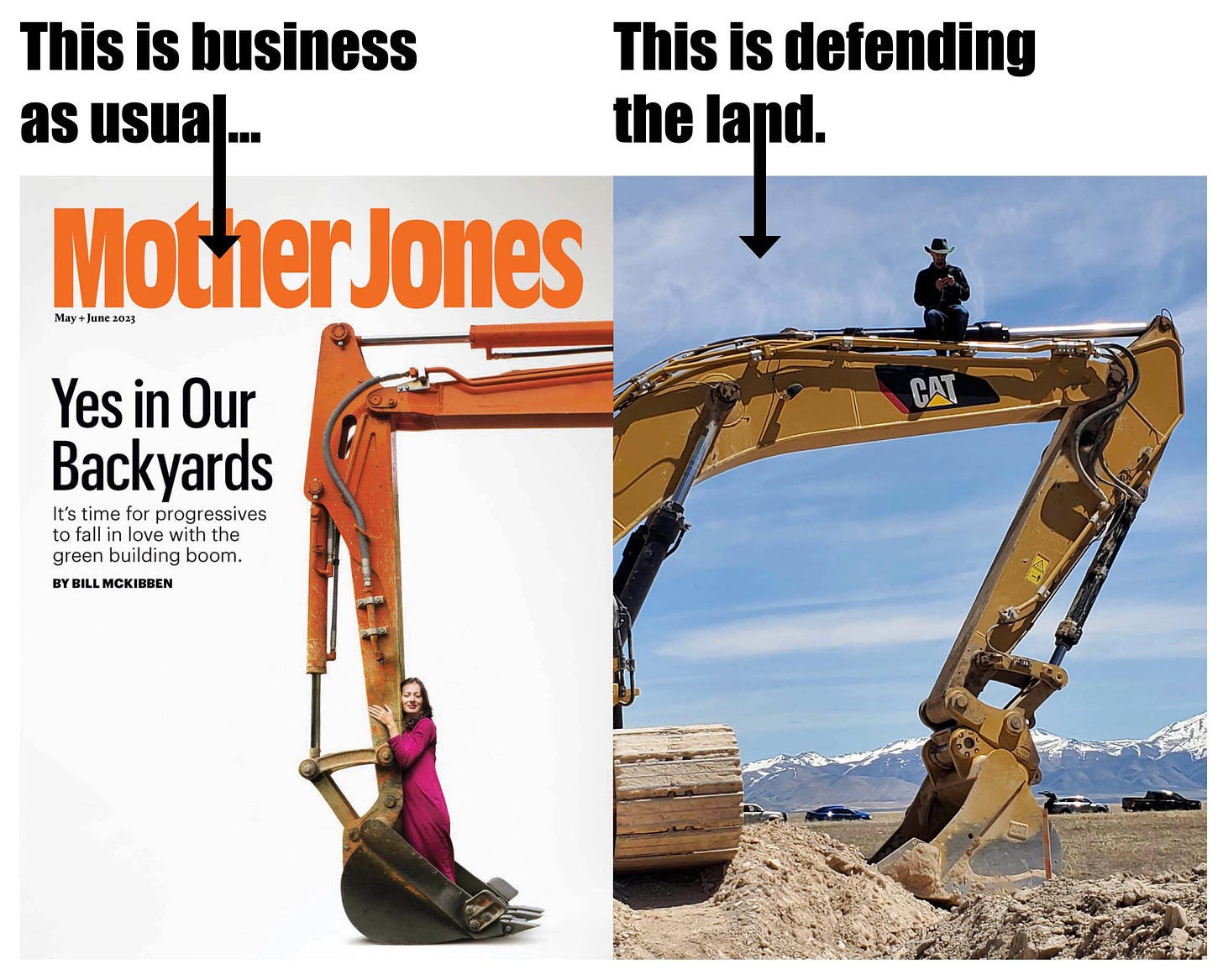

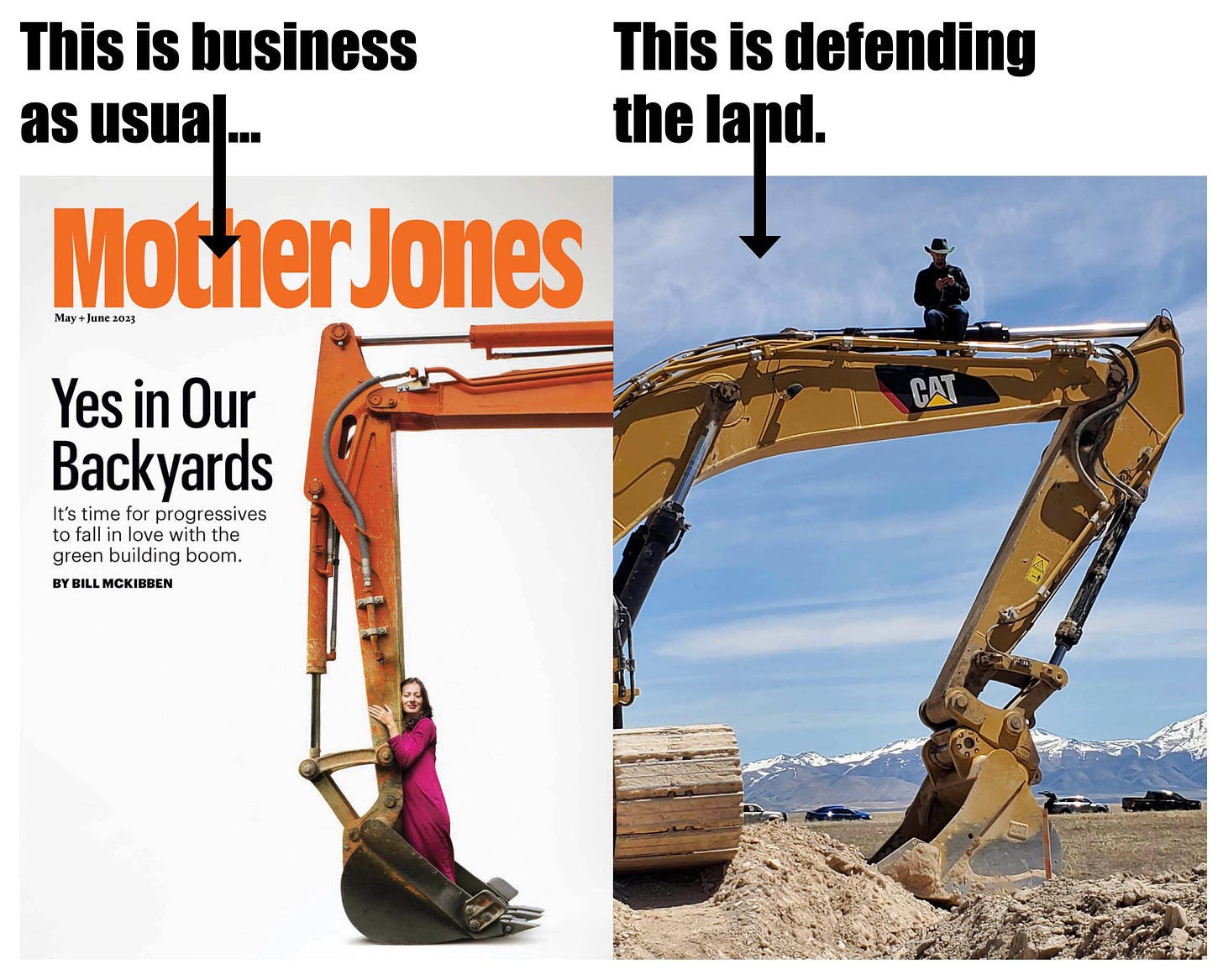

In the past couple of weeks both The Economist and Mother Jones have published covers showing people embracing industrial objects and exhorting “environmentalists” to get on board with the green building boom.

The Economist cover shows a man hugging a massive steel electric grid pylon and says “Hug Pylons Not Trees: The Growth Environmentalism Needs.” The Mother Jones cover shows a woman hugging an excavator, and says “Yes in Our Backyards: It’s time for progressives to fall in love with the green building boom.”

The latter is made even worse by the fact that it is Bill McKibben saying this. We expect relentless pro-industry, pro-growth propaganda from The Economist. But Mother Jones? Bill McKibben? McKibben begins his article in Mother Jones, Getting to Yes, by saying “I’m an environmentalist” and then proceeds to spend multiple pages telling us exactly how he is not an environmentalist but rather a pro-technology industrialist. To solve our “biggest problems” he pleads with us to “say yes” to “solar panels, wind turbines, and factories to make batteries and mines to extract lithium.”

Max Wilbert, co-founder of Protect Thacker Pass, climbed on top of an excavator on April 25, 2023 to protest the Thacker Pass Lithium Mine, currently being constructed in northern Nevada by Lithium Nevada Corporation. He was there with about 25 other people including Northern Paiute Native Americans Dorece Sam and Dean Barlese, who spent the day blocking mine construction and saying prayers to this land considered sacred by their people.

In Max’s book, Bright Green Lies, he describes “environmentalists” like McKibben as “bright greens”. These “environmentalists” understand that environmental problems exist and are serious, but believe that green technology and consumerism will allow us to continue our current lifestyles indefinitely. As Max writes: “The bright greens’ attitude amounts to: ‘It’s less about nature, and more about us.’”

In his Mother Jones article, McKibben illustrates how he’s less about nature, and all about us (meaning humans, our technologies, and our lifestyles). “Emergencies demand urgency,” he writes, and what he urges us is not to stop destroying nature, the source of all life on planet Earth, but rather to destroy more of it, by building more industry and mining more, for “electrons… a crop we badly need.”

McKibben acknowledges that “repeating the mistakes of our history” by building “a lithium mine on sacred territory in Nevada” is “truly unforgivable,” but then immediately dismisses the concerns of regional tribes by saying that “if we can’t make a quick energy transition, then the impact of that will be felt most by the poorest.” Does he not understand that for many traditional cultures and traditional spiritual practitioners, everywhere is sacred? Does he not understand that everywhere not already destroyed by industry is home to someone — sage-grouse, pronghorn, endangered spring snails, swallows, endangered trout, old growth sagebrush, and so many more? Apparently he does not, or perhaps he doesn’t care, because his article is all about promoting industry, nature be damned.

“So there’s one general rule you could derive: If something makes climate change worse, then we shouldn’t do it,” McKibben writes. I agree. Does McKibben think the 150,000 tons of CO2 the Thacker Pass lithium mine will emit per year don’t count? Clearly those emissions will make climate change worse. Does he think that the carbon emissions caused by digging up thousands of acres of ancient soil at Thacker Pass don’t count either? And what about the 700,000 tons per year of molten sulfur trucked into Thacker Pass from oil refineries; where will that molten sulfur come from if it doesn’t come from oil refineries, and do those oil refineries and their CO2 emissions not count? If we use McKibben’s rule, then clearly the Thacker Pass lithium mine should not be built, and yet he urges us to support more lithium mining.

McKibben and those pursuing the “electrify everything” agenda promoted by The Economist and Mother Jones are stuck in blinders about climate change. McKibben exposes these blinders when he writes: “slowing down lithium mining likely means extending the years we keep on mining coal.” He believes that this is our choice: lithium mining and batteries and electric vehicles, or coal and CO2 emissions. To him and the “electrify everything” crowd those are the only two options.

But there is another option: we can resist industrial culture and work to end it. We can block construction equipment rather than embracing it. We can dramatically lower our profligate energy use — no matter how it’s powered. We can protect the land and the natural communities, including human communities, that depend on unspoiled land, unpolluted soil, clean air, and clean water. We can be real environmentalists, deep green environmentalists, who understand that we must live within the limits of the natural world, and work to transform ourselves, our culture, our economy and our politics to put the health and well-being of the natural world first.

We can be more like Max and Dorece and Dean and the other activists who stood their ground to protect the land at Thacker Pass. We can block excavators, not hug them. Our very lives depend on it.

by DGR News Service | Sep 19, 2022 | ANALYSIS, Human Supremacy

By Max Wilbert

David Roberts — a journalist who has written for Vox and Grist and now runs a popular green-tech newsletter — recently shared this on Twitter:

This idea is not new to Mr. Roberts. It actually reflects a decades-long push to make environmentalism mainstream by sacrificing its foundational biocentric values in favor of anthropocentrism.

The organization 350, for example, has released a ‘style guide’ advising activists to “Focus on people. Whenever possible, use visuals to emphasize that climate is a real, tangible human problem—not an abstract [sic] ecological issue.” A later version of the same guide edited the statement to read: “People are the heart of the climate movement … avoid photos of polar bears, icebergs or other images that obscure the real people behind the climate crisis.”

Some see this sort of thing as pragmatic thinking to address a crisis. Others — including me, and despite my love of people — see it as at best a profoundly dangerous mistake, and at worst as enabling colonization of the environmental movement by profit-driven interests.

Last year, me and my co-authors Derrick Jensen and Lierre Keith released our book “Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost Its Way and What to Do About It” (thanks to the wonderful folks at Monkfish Book Publishing Company) which we bookend with this topic. This is an excerpt from Chapter 2, which is titled “Solving for the Wrong Variable,” and from the conclusion of the book:

Once upon a time, environmentalism was about saving wild beings and wild places from destruction. “The beauty of the living world I was trying to save has always been uppermost in my mind,” Rachel Carson wrote to a friend as she finished the manuscript that would become Silent Spring. “That, and anger at the senseless, brutish things that were being done.” She wrote with unapologetic reverence of “the oak and maple and birch” in autumn, the foxes in the morning mist, the cool streams and the shady ponds, and, of course, the birds: “In the mornings, which had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, and wrens, and scores of other bird voices, there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marshes.” Her editor noted that Silent Spring required a “sense of almost religious dedication” as well as “extraordinary courage.” Carson knew the chemical industry would come after her, and come it did, in attacks as “bitter and unscrupulous as anything of the sort since the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species a century before.” Seriously ill with the cancer that would kill her, Carson fought back in defense of the living world, testifying with calm fortitude before President John F. Kennedy’s Science Advisory Committee and the U.S. Senate. She did these things because she had to. “There would be no peace for me,” she wrote to a friend, “if I kept silent.”

Carson’s work inspired the grassroots environmental movement; the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA); and the passage of the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act. Silent Spring was more than a critique of pesticides—it was a clarion call against “the basic irresponsibility of an industrialized, technological society toward the natural world.”

Today’s environmental movement stands upon the shoulders of giants, but something has gone terribly wrong. Carson didn’t save the birds from DDT so that her legatees could blithely offer them up to wind turbines. We are writing this book because we want our environmental movement back.

Mainstream environmentalists now overwhelmingly prioritize saving industrial civilization over saving life on the planet. The how and the why of this institutional capture is the subject for another book, but the capture is near total. For example, Lester Brown, founder of the Worldwatch Institute and Earth Policy Institute—someone who has been labeled as “one of the world’s most influential thinkers” and “the guru of the environmental movement”—routinely makes comments like, “We talk about saving the planet…. But the planet’s going to be around for a while. The question is, can we save civilization? That’s what’s at stake now, and I don’t think we’ve yet realized it.” Brown wrote this in an article entitled “The Race to Save Civilization.”

The world is being killed because of civilization, yet what Brown says is at stake, and what he’s racing to save, is precisely the social structure causing the harm: civilization. Not saving salmon. Not monarch butterflies. Not oceans. Not the planet. Saving civilization.

Brown is not alone. Peter Kareiva, chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy, more or less constantly pushes the line that “Instead of pursuing the protection of biodiversity for biodiversity’s sake, a new conservation should seek to enhance those natural systems that benefit the widest number of people…. Conservation will measure its achievement in large part by its relevance to people.”

Bill McKibben, who works tirelessly and selflessly to raise awareness about global warming, and who has been called “probably America’s most important environmentalist,” constantly stresses his work is about saving civilization, with articles like “Civilization’s Last Chance,”11 or with quotes like, “We’re losing the fight, badly and quickly—losing it because, most of all, we remain in denial about the peril that human civilization is in.”

We’ll bet you that polar bears, walruses, and glaciers would

have preferred that sentence ended a different way.

In 2014 the Environmental Laureates’ Declaration on Climate Change was signed by “160 leading environmentalists from 44 countries” who were “calling on the world’s foundations and philanthropies to take a stand against global warming.” Why did they take this stand? Because global warming “threatens to

cause the very fabric of civilization to crash.” The declaration concludes: “We, 160 winners of the world’s environmental prizes, call on foundations and philanthropists everywhere to deploy their endowments urgently in the effort to save civilization.” Coral reefs, emperor penguins, and Joshua trees probably wish that sentence would have ended differently. The entire declaration, signed by “160 winners of the world’s environmental prizes,” never once mentions harm to the natural world. In fact, it never mentions the natural world at all.

Are leatherback turtles, American pikas, and flying foxes “abstract ecological issues,” or are they our kin, each imbued with their own “wild and precious life”?

Wes Stephenson, yet another climate activist, has this to say: “I’m not an environmentalist. Most of the people in the climate movement that I know are not environmentalists. They are young people who didn’t necessarily come up through the environmental movement, so they don’t think of themselves as environmentalists. They think of themselves as climate activists and as human rights activists. The terms ‘environment’ and ‘environmentalism’ carry baggage historically and culturally. It has been more about protecting the natural world, protecting other species, and conservation of wild places than it has been about the welfare of human beings. I come at it from the opposite direction. It’s first and fore- most about human beings.”

Note that Stephenson calls “protecting the natural world, protecting other species, and conservation of wild places” baggage.

Naomi Klein states explicitly in the film This Changes Everything: “I’ve been to more climate rallies than I can count, but the polar bears? They still don’t do it for me. I wish them well, but if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that stopping climate change isn’t really about them, it’s about us.”

And finally, Kumi Naidoo, former head of Greenpeace International, says: “The struggle has never been about saving the planet. The planet does not need saving.”

When Naidoo said that, in December 2015, it was 50 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than normal at the North Pole, above freezing in the winter.

##

I (Derrick) wrote this for a friend’s wedding.

> Each night the frogs sing outside my window. “Come to me,” they sing. “Come.” This morning the rains came, each drop meeting this particular leaf on this particular tree, then pooling together to join the ground. Love. The bright green of this year’s growth of redwood trees against the dark of shadows, other trees, tree trunks, foliage, all these plants, reaching out, reaching up. I am in love. With you. With you. With the world. With this place. With each other. Redwoods cannot stand alone. Roots burrow through the soil, reaching out to each other, to intertwine, to hold up these tallest of trees, so they may stand together, each root, each tree, saying to each other, “Come to me. Come.” What I want to know is this: What do those roots feel at first touch, first embrace? Do they find this same homecoming I find each time in you, in your eyes, the pale skin of your cheek, your neck, your belly, the backs of your hands? And the water. It is evening now, and the rain has stopped. Yet the water still falls, drop by drop from the outstretched arms of trees. I want to know, as each drop let’s go its hold, does it say, and does the ground say to it, as I say to you now, “Come to me. Come.”

In the 15 years since that wedding, the frogs in my pond have suffered reproductive failure, which is science-speak for their off- spring dying, baby after baby, year after year. Their songs began to lessen. At first their songs were so loud you could not hold a (human) conversation outside at night, and then you could. The first spring this happened I thought it might just be a bad year. The second spring I sensed a pattern. The third spring I knew something was wrong. I’d also noticed the eggs in their sacs were no longer small black dots, as before, but were covered in what looked like white fur. A little internet research and a few phone calls to herpetologists revealed the problem to me. The egg sacs were being killed by a mold called saprolegnia. It wasn’t the mold’s fault. Saprolegnia is ubiquitous, and eats weak egg sacs, acting as part of a clean-up crew in ponds. The problem is that this culture has depleted the ozone layer, which has allowed more UV-B to come through: UV-B weakens egg sacs in some species.

What do you do when someone you love is being killed? And what do you do when the whole world you love is being killed? I’m known for saying we should use any means necessary to stop the murder of the planet. People often think this is code language for using violence. It’s not. It means just what it says: any means necessary.

UV-B doesn’t go through glass, so about once a week between December and June, I get into the pond to collect egg sacs to put in big jars of water on my kitchen table. When the egg sacs hatch, I put the babies back in the pond. If I bring in about five egg sacs per week for 20 weeks, and if each sac has 15 eggs in it, and if there’s a 10 percent mortality on the eggs instead of a 90 percent mortality, that’s 2,400 more tadpoles per year. If one percent of these survive their first year, that’s 24 more tadpoles per year who survive. I fully recognize that this doesn’t do anything for frogs in other ponds. It doesn’t help the newts who are also disappearing from this same pond, or the mergansers, dragonflies, or caddisflies. It doesn’t do anything for the 200 species this culture causes to go extinct each and every day. But it does help these.

I don’t mean to make too big a deal of this.

One of my earliest memories is from when I was five years old, crying in the locker room of a YMCA where I was taking swimming lessons, because the water was so cold. I really don’t like cold water. So, I have to admit I don’t get all the way into the water when I go into my pond to help the frogs. I only get in as far as my thighs. But this isn’t, surprisingly enough, entirely because of my cold-water phobia. It’s because of a creature I’ve seen in the pond a few times, a giant water bug, which is nicknamed Toe-Biter. My bug book says they’re about an inch and a half long, but every time I get in the pond, I’m sure they are five or six inches. And I can’t stop thinking about the deflated frog-skin sacks I’ve seen (the giant water bug injects a substance that liquefies the frog’s insides, so they can be sucked out as through a straw). I’ve read that the bugs sometimes catch small birds. So, you’ll note I only go into the pond as deep as my thighs—and no deeper. Second, I have to admit that sometimes I’m not very smart. It took me several years of this weekly cold-water therapy to think of what I now perceive as one of the most important phrases in the English language—“waterproof chest waders”—and to get some.

What do you do when someone you love is being killed? It’s pretty straightforward. You defend your beloved. Using any means necessary.

##

We get it. We, too, like hot showers and freezing cold ice cream, and we like them 24/7. We like music at the touch of a button or, now, a verbal command. We like the conveniences this way of life brings us. And it’s more than conveniences. We know that. We three co-authors would be dead without modern medicine. But we all recognize that there is a terrible trade-off for all this: life on the planet. And no individual’s conveniences—or, indeed, life—is worth that price.

The price, though, is now invisible. This is the willful blindness of modern environmentalism. Like Naomi Klein and the polar bears, the real world just “doesn’t do it” for too many of us. To many people, including even some of those who consider themselves environmentalists, the real world doesn’t need our help. It’s about us. It’s always “about us.”

##

Decades ago, I (Derrick) was one of a group of grassroots environmental activists planning a campaign. As the meeting started, we went around the table saying why we were doing this work. The answers were consistent, and exemplified by one person who said, simply, “For the critters,” and by another person who got up from the table, walked to her desk, and brought back a picture. At first, the picture looked like a high-up part of the trunk of an old-growth Douglas fir tree, but when I looked more closely, I saw a small spotted owl sticking her camouflaged head out of a hole in the center of the tree’s trunk. The activist said, “I’m doing it for her.”

##

The goal has been shifted, slowly and silently, and no one seems to have noticed. Environmentalists tell the world and their organi- zations that “it’s about us.” But some of us refuse to forget the last spotted owls in the last scrap of forest, the wild beings and wild places. Like Rachel Carson before us, there will be no peace for us if we keep silent while the critters, one by one, are disappeared. Our once and future movement was for them, not us. We refuse to solve for the wrong variable. We are not saving civilization; we are trying to save the world.

[And this part comes from the conclusion of the book:]

… throughout this book, we’ve repeated Naomi Klein’s comments about polar bears not doing it for her. Not to be snarky, but instead because that’s the single most important passage in this book.

Although we’ve spent hundreds of pages laying out facts, ultimately this book is about values. We value something different than do bright greens. And our loyalty is to something different. We are fighting for the living planet. The bright greens are fighting to continue this culture—the culture that is killing the planet. Seems like the planet doesn’t do it for them.

Early in this book we quoted some of the bright greens, including Lester Brown: “The question is, can we save civilization? That’s what’s at stake now, and I don’t think we’ve yet realized it.” And Peter Kareiva, chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy: “Instead of pursuing the protection of biodiversity for biodiversity’s sake, a new conservation should seek to enhance those natural systems that benefit the widest number of people.” And climate scientist Wen Stephenson: “The terms ‘environment’ and ‘environmental- ism’ carry baggage historically and culturally. It has been more about protecting the natural world, protecting other species, and conservation of wild places than it has been about the welfare of human beings. I come at it from the opposite direction. It’s first and foremost about human beings.” And Bill McKibben: “We’re losing the fight, badly and quickly—losing it because, most of all, we remain in denial about the peril that human civilization is in.”

Do we yet see the pattern?

And no, we’re not losing that fight because “we remain in denial about the peril that human civilization is in.” We’re losing that fight because we’re trying to save industrial civilization, which is inherently unsustainable.

We, the authors of this book, also like the conveniences this culture brings to us. But we don’t like them more than we like life on the planet.

We should be trying to save the planet—this beautiful, creative, unique planet—the planet that is the source of all life, the planet without whom we all die.

We are in the midst of a battle for the soul of the environmental movement, and I, for one, will not forget the forests, the birds, the fish, the antelope, the bears, the spiders, the plankton — all those beings who hold the world together in their weaving, who share common ancestry with us. Nor will I forget the mountains whose minerals make up our bones, the rivers whose waters flow in our veins, the Earth itself who is our mother. These beings are family, and I will not turn away from them.

David happens to live in my hometown, Seattle. David – if you read this, I’d like to invite you to get a cup of coffee next time I’m in town. I’ll give you a copy of #BrightGreenLies and we can talk.

Postscript: The type of thinking being promoted by David Roberts has profound consequences for the living world. For the past two years, I’ve been fighting to “Protect Thacker Pass” — a beautiful, biodiverse sagebrush-steppe in the northern Great Basin of Nevada — from destruction for a lithium mine.

The Bright Green worldview sees lithium as a necessary resource to transition away from fossil fuels and save civilization from global warming, and so Bright Greens promote lithium mining, vast solar arrays in desert tortoise habitat, and offshore wind energy development in the last breeding ground of the Atlantic Right Whale. And if some endangered wildlife has to be killed, some water poisoned, and some Native American sacred sites destroyed, well, that’s just an acceptable cost to save civilization. And so vast subsidies (see the inflation Reduction Act, for example) are being mobilized to convert yet more wild land into industrial energy and mining sacrifice zones.

Around the world, nature retreats and civilization grows.

Featured image by Max Wilbert: a spring gushing from the rock high in the western mountains.

by DGR News Service | Nov 2, 2021 | Climate Change, Education, Human Supremacy, Indirect Action, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

This is an excerpt from the book Bright Green Lies, P. 20 ff

By Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith and Max Wilbert

What this adds up to should be clear enough, yet many people who should know better choose not to see it. This is business-as- usual: the expansive, colonizing, progressive human narrative, shorn only of the carbon. It is the latest phase of our careless, self-absorbed, ambition-addled destruction of the wild, the unpolluted, and the nonhuman. It is the mass destruction of the world’s remaining wild places in order to feed the human economy. And without any sense of irony, people are calling this “environmentalism.”1 —PAUL KINGSNORTH

Once upon a time, environmentalism was about saving wild beings and wild places from destruction. “The beauty of the living world I was trying to save has always been uppermost in my mind,” Rachel Carson wrote to a friend as she finished the manuscript that would become Silent Spring. “That, and anger at the senseless, brutish things that were being done.”2 She wrote with unapologetic reverence of “the oak and maple and birch” in autumn, the foxes in the morning mist, the cool streams and the shady ponds, and, of course, the birds: “In the mornings, which had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, and wrens, and scores of other bird voices, there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marshes.”3 Her editor noted that Silent Spring required a “sense of almost religious dedication” as well as “extraordinary courage.”4 Carson knew the chemical industry would come after her, and come it did, in attacks as “bitter and unscrupulous as anything of the sort since the publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species a century before.”5 Seriously ill with the cancer that would kill her, Carson fought back in defense of the living world, testifying with calm fortitude before President John F. Kennedy’s Science Advisory Committee and the U.S. Senate. She did these things because she had to. “There would be no peace for me,” she wrote to a friend, “if I kept silent.”6

Carson’s work inspired the grassroots environmental movement; the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA); and the passage of the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act. Silent Spring was more than a critique of pesticides—it was a clarion call against “the basic irresponsibility of an industrialized, technological society toward the natural world.”7 Today’s environmental movement stands upon the shoulders of giants, but something has gone terribly wrong with it. Carson didn’t save the birds from DDT so that her legatees could blithely offer them up to wind turbines. We are writing this book because we want our environmental movement back.

Mainstream environmentalists now overwhelmingly prioritize saving industrial civilization over saving life on the planet. The how and the why of this institutional capture is the subject for another book, but the capture is near total. For example, Lester Brown, founder of the Worldwatch Institute and Earth Policy Institute—someone who has been labeled as “one of the world’s most influential thinkers” and “the guru of the environmental movement”8—routinely makes comments like, “We talk about saving the planet.… But the planet’s going to be around for a while. The question is, can we save civilization? That’s what’s at stake now, and I don’t think we’ve yet realized it.” Brown wrote this in an article entitled “The Race to Save Civilization.”9

The world is being killed because of civilization, yet what Brown says is at stake, and what he’s racing to save, is precisely the social structure causing the harm: civilization. Not saving salmon. Not monarch butterflies. Not oceans. Not the planet. Saving civilization. Brown is not alone. Peter Kareiva, chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy, more or less constantly pushes the line that “Instead of pursuing the protection of biodiversity for biodiversity’s sake, a new conservation should seek to enhance those natural systems that benefit the widest number of [human] people…. Conservation will measure its achievement in large part by its relevance to [human] people.”10 Bill McKibben, who works tirelessly and selflessly to raise awareness about global warming, and who has been called “probably America’s most important environmentalist,” constantly stresses his work is about saving civilization, with articles like “Civilization’s Last Chance,”11 or with quotes like, “We’re losing the fight, badly and quickly—losing it because, most of all, we remain in denial about the peril that human civilization is in.”12

We’ll bet you that polar bears, walruses, and glaciers would have preferred that sentence ended a different way.

In 2014 the Environmental Laureates’ Declaration on Climate Change was signed by “160 leading environmentalists from 44 countries” who were “calling on the world’s foundations and philanthropies to take a stand against global warming.” Why did they take this stand? Because global warming “threatens to cause the very fabric of civilization to crash.” The declaration con- cludes: “We, 160 winners of the world’s environmental prizes, call on foundations and philanthropists everywhere to deploy their endowments urgently in the effort to save civilization.”13

Coral reefs, emperor penguins, and Joshua trees probably wish that sentence would have ended differently. The entire declaration, signed by “160 winners of the world’s environmental prizes,” never once mentions harm to the natural world. In fact, it never mentions the natural world at all.

Are leatherback turtles, American pikas, and flying foxes “abstract ecological issues,” or are they our kin, each imbued with their own “wild and precious life”?14 Wes Stephenson, yet another climate activist, has this to say: “I’m not an environmentalist. Most of the people in the climate movement that I know are not environmentalists. They are young people who didn’t necessarily come up through the environmental movement, so they don’t think of themselves as environmentalists. They think of themselves as climate activists and as human rights activists. The terms ‘environment’ and ‘environmentalism’ carry baggage historically and culturally. It has been more about protecting the natural world, protecting other species, and conservation of wild places than it has been about the welfare of human beings. I come at from the opposite direction. It’s first and foremost about human beings.”15

Note that Stephenson calls “protecting the natural world, protecting other species, and conservation of wild places” baggage. Naomi Klein states explicitly in the film This Changes Everything: “I’ve been to more climate rallies than I can count, but the polar bears? They still don’t do it for me. I wish them well, but if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that stopping climate change isn’t really about them, it’s about us.”

And finally, Kumi Naidoo, former head of Greenpeace International, says: “The struggle has never been about saving the planet. The planet does not need saving.”16 When Naidoo said that, in December 2015, it was 50 degrees Fahrenheit at the North Pole, much warmer than normal, far above freezing in the middle of winter.

1 Paul Kingsnorth, “Confessions of a recovering environmentalist,” Orion Magazine, December 23, 2011.

2 Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (Greenwich, CT: Fawcett Publishing, 1962), 9.

3 Ibid, 10.

4 Ibid, 8.

5 Ibid, 8.

6 Ibid, 8.

7 Ibid, 8.

8 “Biography of Lester Brown,” Earth Policy Institute.

9 Lester Brown, “The Race to Save Civilization,” Tikkun, September/October 2010, 25(5): 58.

10 Peter Kareiva, Michelle Marvier, and Robert Lalasz, “Conservation in the Anthropocene: Beyond Solitude and Fragility,” Breakthrough Journal, Winter 2012.

11 Bill McKibben, “Civilization’s Last Chance,” Los Angeles Times, May 11, 2008.

12 Bill McKibben, “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math,” Rolling Stone, August 2, 2012.

13 “Environmental Laureates’ Declaration on Climate Change,” European Environment Foundation, September 15, 2014. It shouldn’t surprise us that the person behind this declaration is a solar energy entrepreneur. It probably also shouldn’t surprise us that he’s begging for money.

14 “Wild and precious life” is from Mary Oliver’s poem “The Summer Day.” House of Light (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1992).

15 Gabrielle Gurley, “From journalist to climate crusader: Wen Stephenson moves to the front lines of climate movement,” Commonwealth: Politics, Ideas & Civic Life in Massachusetts, November 10, 2015.

16 Emma Howard and John Vidal, “Kumi Naidoo: The Struggle Has Never Been About Saving the Planet,” The Guardian, December 30, 2015.