by DGR News Service | Apr 17, 2020 | The Problem: Civilization

Whether by war, famine, resource depletion, socioeconomic failure, or destruction of the natural environment, all empires eventually crumble. What will happen when the collapse of the American empire culminates?

By Max Wilbert

History is a graveyard of civilizations: the Western Chou, the Mayan, the Harappan, the Mesopotamian, the Olmec, the Chacoans, the Hohokam, the Mississippian, the Tiahuanaco, the Mycenean, the Roman, and countless others.

These societies were overrun by disease, or war, or famine. In most cases, they undermined their own ecological foundations—a situation that may sound familiar.

“Collapse,” writes archaeologist and historian Joseph Tainter, “is a recurrent feature of human societies.” But there is an important distinction to be made between societies that create an ideology of growth and an economy of ecological imperialism, and those that do not.

To choose two examples, both the San people of the Kalahari and the various Aboriginal Nations, in what is now Australia, existed in a more or less stable-state for tens of thousands of years. But these were not civilizations, according to the definition I am using. In other words, they were not ecological imperialists, but rather ecological participants.

For the average person living today in Washington D.C., Beijing, or London, the collapse of civilization is hard to fathom. Similarly, the people of ancient cities could not imagine their world crumbling around them—until it did.

With the globalization of capitalism and the neoliberal free-trade economy, industrial civilization now dominates the entire planet.

Goods and services are traded around the world. The average dinner plate contains ingredients grown in five different nations. Rather than living in an empire with discrete boundaries, we live within a global civilization. It feels stable, permanent.

At least, it did until recently. The past month has upended many of our preconceptions. And the reality, of course, is that modern civilization is neither stable nor permanent. This society is destroying the ecological foundation that not only allows it to exist, but supports the fabric of life itself.

People living in rich nations are insulated from the reality of this ecological collapse, since our food no longer comes from the land where we live, but is imported from far away. Technology allows us to ignore the collapse of fish populations, of plankton populations, of topsoil. When the cod fisheries collapse, the industrial fishing corporations can simply begin to fish another far-flung corner of the globe, until that ocean too is devoid of fish. When the soil is lifeless, desiccated, and eroded, industrial farmers can simply apply more chemical fertilizers.

Modern life is based on the use of non-renewable resources, and on the over-exploitation of renewable resources. By definition, this cannot last.

The decline and fall of the American empire has already begun.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Chris Hedges, in his book America: The Farewell Tour, estimates that the Chinese will overtake the United States for world hegemony sometime around 2030. Historian of empire Alfred W. McCoy, in his latest book In the Shadows of the American Century, agrees with Hedges.

McCoy estimates that, no later than 2030, the US dollar will cease to the currency of global trade. This “reserve currency” status makes the US the center of the global economy, and directly provides the US economy with more than $100 billion in “free money” per year. As McCoy writes, “One of the prime benefits of global power is being on the winning side of grand imperial bargain: you get to send the nations of the world bundles of brightly colored paper, whether British pound notes or US Treasury bills, and they happily hand over goods of actual value like automobiles, minerals, or oil.” A fall from reserve currency status will lead, McCoy says, to sustained “rising prices, stagnant wages, and fading international competitiveness” in the United States.

“Will there be a soft landing for America thirty or forty years from now?

Don’t bet on it. The demise of the United States as the preeminent global power could come far more quickly than anyone imagines. Despite the aura of omnipotence empires often project, most are surprisingly fragile, lacking the inherent strength of even a modest nation-state.”

As he reminds us, the Portuguese empire collapsed in a year, the Soviet Union in two years, and Great Britain in seventeen.

The mechanics of the decline and fall of the U.S. American empire have been well documented by others. But what hasn’t been discussed, and what I am interested in exploring here, is the implications of this decline and collapse for revolutionaries.

What will the decline of the American empire mean for those of us fighting for justice?

As revolutionaries, we must be “internationalists.” That is, we must understand and design our strategy in a way that confronts capitalism, civilization, and empire as global systems, not merely national ones. So in this sense, a reorientation of global power is nothing more than that—a shifting of polarity.

We need to be prepared for the international impacts, but also the domestic implications of these shifts. As the axis of global power moves away from Washington and towards “the world island”—Beijing, New Delhi, Moscow—we are seeing a rise in imperial impetuousness, racism, and reaction typified by Trump. Author Richard Powers calls this “a tantrum in the face of a crumbling control fantasy.”

How will the collapse of American empire play out?

Will it (ironically) mirror the decline of the USSR, where Russia now has the most billionaires per capita in the world, an ex-KGB dictator, and an economic system dominated by collaborations between organized crime and corporate capitalism? Will it mirror the more gradual, socially moderated collapse of the UK? Will we see a full-on Children of Men or Elysium-style dystopia?

As society becomes more volatile, those who have best prepared themselves will be the most likely to survive and influence the course of the future. As Vince Emanuele has written, “the next recession will be the icing on the cake. Once the economy collapses and the American Empire is forced to retreat from various parts of the globe, immigrants, Muslims, blacks, and poor whites will be the targets of state and non-state violence. The only way we’ll survive is through community and organizing.”

Vince wrote those words months ago. Now, that recession has now arrived. Times have changed faster than minds have changed.

How should we respond to the current situation?

In crisis lies opportunity. Emergencies clarify things. Bullshit gets less important and truth becomes more self-evident. That is the case now, as well. Reality is imposing itself on us. Any faith in capitalism, in globalization—hell, in the grocery store—has been shattered. The ruling class is weakened. And the lessons are clear.

Globalization is dying. Sure, the system might repair itself and reassemble transnational supply chains. Coronavirus is unlikely to end it all. But the fragility and unreliability of just-in-time industrial food delivery is now obvious. We need to build robust local food systems using sustainable, biodiverse and soil-growing methods.

Organizations already exist that are doing this work. They need funding and support to rapidly scale up. Local governments should be pressured to direct funds towards these projects and make land available for urban and peri-urban gardening, and people should begin volunteer brigades to do the labor.

Food is just the beginning. Globalization isn’t a threat just because it will collapse; it is a threat if it continues as well. Local production of water, clothing, housing, healthcare, and other basic necessities must begin as well. There are cooperative and truly sustainable methods with which this could be done.

Mutual aid is the new rallying cry of the 21st century. There will be no individual survival. Our best hope for creating a better world—and for survival—lies in banding together, building small-scale, localized communities based on human rights and sustainability, pressuring local governments to join—or simply replacing them if they cannot respond—and preparing for the challenges to come.

The longer business as usual continues, the worse off we will be. Governments are already descending into fascism in a vain attempt to be “great again.” Expansions of the surveillance state, police powers, and repression will only deepen as ecological collapse undermines stability.

Each day more forests logged, more carbon in the atmosphere, more species driven extinct. More wealth in the hands of the elite and more poverty, disease, and hopelessness for the people. Remember: the air is cleaner now than you have ever seen it. It can only remain that way if these global supply chains do not re-start.

The sooner we dismantle industrial supply chains, the better off the people and the planet will be. Tim Garrett, a climate scientist at the University of Utah, says that “Only complete economic collapse will prevent runaway global climate change.” He bases this conclusion on climate models he designs. Garrett’s calculations show that industrial civilization is a “heat machine,” and only the total collapse of industrial civilization will permit life on Earth to survive the ongoing mass extinction, and global warming.

To borrow Marxist language, we need to not only seize the means of production away from the ruling class, we need to destroy much of the means of production, because what it produces is ecocide.

Collapse Does Not Have to Be Bad

Some people inaccurately view collapse as a state of total lawlessness; in other words, the disintegration of society. More accurately, collapse refers to a rapid, radical simplification in society, such as the breakdown of “normal” economic, social, and political institutions.

Under this definition, a more or less global collapse of industrial civilization within the next 50 or 100 years—possibly much sooner—is almost a certainty. A NASA-commissioned study in the journal of Ecological Economics found a few years ago that “the system is moving towards an impending collapse” due to destruction of the planet and economic stratification. They write that their model, using conditions “closely reflecting the reality of the world today… find[s] that collapse is difficult to avoid.”

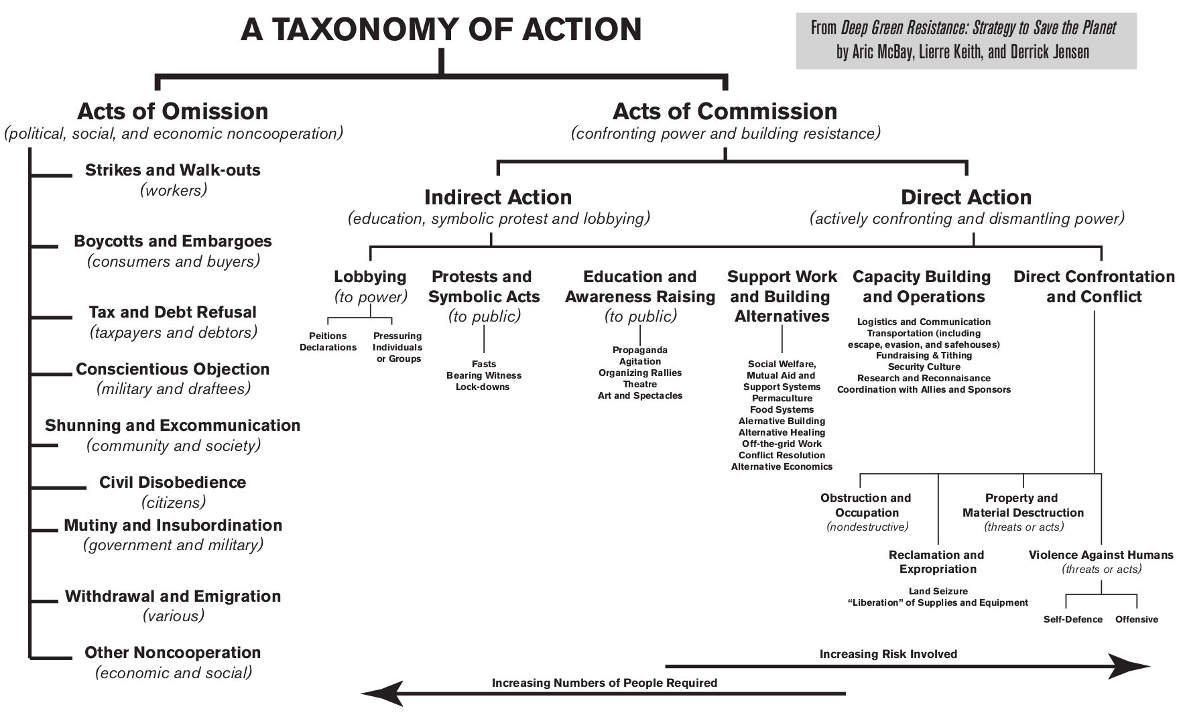

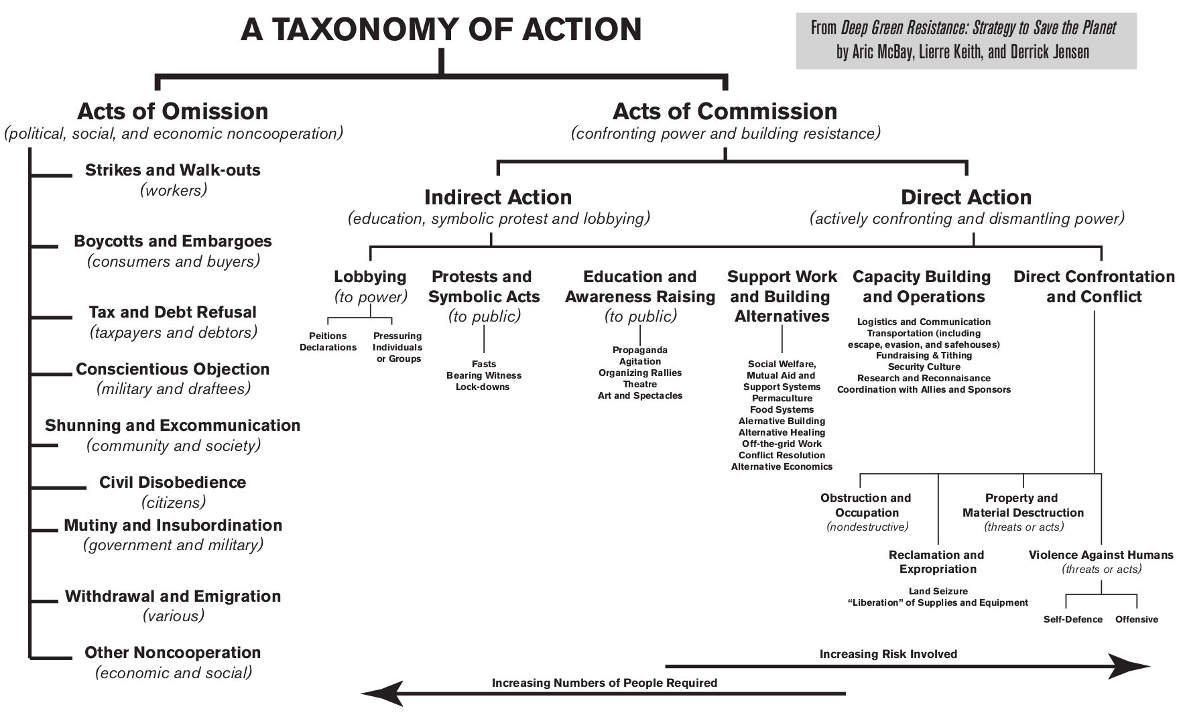

This does not have to be a bad thing. A managed collapse, or reduction in complexity, is the best way to ensure human rights and sustainability moving forward. In the book Deep Green Resistance, the authors advocate for a political movement that could help speed up certain aspects of collapse, while fighting others, to maximize good outcomes. As the book explains:

“Many different mechanisms drive collapse, not all equally desirable. Some [can be] intentionally accelerated and encouraged, while others are slowed or reduced. Energy decline by decreasing consumption of fossil fuels is a mechanism of collapse highly beneficial to the planet and humans, and that mechanism is encouraged. Ecological collapse through habitat destruction and biodiversity crash is also a mechanism of collapse, but is slowed or stopped whenever possible… The collapse of large authoritarian political structures allows small-scale participatory structures. The collapse of global industrial capitalism allows local systems of exchange, cooperation, and mutual aid.”

Uncontrolled collapse is a dire alternative. Even now, local and regional collapses are occurring around the globe. This is especially true in places like Syria, Libya, Pakistan, and Iraq where ecological destruction has combined with war.

But the problems are global. Water shortages, refugee crises, religious extremism, exploding population and consumption, toxification, mass extinction, soil drawdown, desertification, and extreme weather are all driving increased instability. It is emerging first in the poorest countries, but it is spreading fast.

Consider: there may be 1 billion climate refugees by 2050. That’s 30 years from now.

Like revolutions and climate change, collapse is an organic process driven by the interplay of countless human and non-human factors, not a single event.

The world is changing.

We need to plan for tomorrow rather than building strategies purely based on the past. These times call for a two-pronged approach. First, we must build additional resiliency into our communities, relocalizing our food systems and reducing and eliminating reliance on big business and national/state government alike. Second, we must be prepared to take advantage of coming shocks to the economic and political system. We can use these breaks in normality as openings to dismantle oppressive systems of power and the physical infrastructure that is destroying our world.

Max Wilbert is a political organizer and wilderness guide. His essays have been published in Earth Island Journal, Counterpunch, and elsewhere. His second book, Bright Green Lies, is scheduled for release in early 2021.

Featured image by the author.

by DGR News Service | Mar 16, 2020 | Building Alternatives, Culture of Resistance, Defensive Violence, Movement Building & Support, The Problem: Civilization, The Solution: Resistance

This is an edited transcript of the interview Sam Mitchell from Collapse Chronicles conducted with DGR Member Max Wilbert.

Sam Mitchell: It is an absolutely beautiful sunny winter day here in the great state of Texas, and the opening bell of the year 2020 and you have found your way to collapse chronicles.

My name is Sam Mitchell and what we do here obviously, as we chronicle the collapse of global industrial civilization and the planet. And guys, before I get into this I just want to give a little bit of a warning and a disclaimer. I have mentioned many times, because I bring a guest on to the show, it does not necessarily mean that I am advocating everything my guests are getting ready to say. I just want to make that clear to Homeland Security. Anyone else listening to this? I am not necessarily advocating what we’re getting ready to hear, but I do think it is a voice we need to hear. And who we’re going to be hearing is a recommendation I received from none other than Derrick Jensen. And this is this fellow named Max Wilbert, who is a buddy of Derrick’s.

And so for those of you not aware of Max, I have read out some of his stuff in the past here. From his Website:

Max Wilbert is a third-generation dissident who grew up in Seattle’s post-WTO anti-globalization and undoing racism movement. He has been an organizer for more than 15 years. Max is a longtime member of Deep Green Resistance and serves on the board of a small, grassroots non-profit. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Environmental Communication and Advocacy from Huxley College. His first book, a collection of pro-feminist and environmental essays written over a six-year period, was released in 2018. He is co-author of the forthcoming book “Bright Green Lies,” which looks at the problems with mainstream so-called “solutions” to the climate crisis.

And here on his Website, Max says of himself, “I am part of a revolutionary movement rooted in ecology, anti-racism, feminism and human and nonhuman rights that aims to dismantle the global culture of empire — read industrial civilization — by any means necessary.“

Max Wilbert, come on and say hi to the folks, and we’re going to dive right into this rollicking conversation.

Max Wilbert: All right, Sam, thanks for having me on the show. It’s good to be here. And thanks for that intro.

Sam Mitchell: OK. So, guys, anyway, my first thought was I was going to build up to this quote I’m getting ready to read from Max, but I’ve said, what the hell? Let’s just dive right into it. We’re not going to read this. It’s the laundry list of everything that is wrong with the global industrial civilization and the ongoing collapse of a planet. We’re going to dive right into what we need to do about it. And this is what Max Wilbert wrote a while back, and we’re just going to pick up from here. So to kick off this conversation, here’s what Max had to say:

“We need to build legitimate movements to dismantle global capitalism. All work is useful towards this end. However, I see no way this goal will be achieved without force. The best methods I have come across for achieving this rely on a dedicated cadre forming small, highly mobile and trained strike forces. These forces should target key nodes of global industrial infrastructure, such as shipping, communication, finance, energy, etc. and destroy them with the goal of inciting cascading systems failure. The interconnected global economy is vulnerable to this type of attack because of how interdependent it is. If the right targets are chosen and effectively attacked, the entire thing could come crashing down.”

Max Wilbert, that was a mouthful. Amplify and clarify, which you have defined as Decisive Ecological Warfare.

Max Wilbert: Absolutely. Thanks for reading that quote out. That was from an interview I did with a French friend of mine a while ago. I tried to lay it out as straightforwardly as I could in that article. And, you know, it sounds pretty extreme to a lot of people. And it sounds like, I think, what the government would call ecoterrorism, and a lot of people would be very terrified by hearing what you just read. And I’m sure a lot of listeners are sitting back in their seats and thinking, what is this all about? This guy’s a nut job, you know. I guess I want to push back on that a little bit. You know, I don’t feel like an extremist. I don’t think that I am somebody who’s crazy. I think that I’m somebody who’s looking at the political realities and the ecological realities of the situation we find ourselves in as a species, and trying to come up with a reasonable response to that. And to me, that reasonable response, it’s not going to rely on the government. I think a lot of your readers probably are on the same pages as me with this. And I think you probably are as well. But look at the incompetence of governments around the world to address the climate crisis and all kinds of different issues. The idea that they’re going to solve these converging problems that we’re facing in an ecological sense is a pipe dream. It’s just not happening. There’s no evidence that it’s happening.

Everything is getting worse day after day after day. And, you know, emissions continue to rise, year after year. So, if government isn’t going to solve it, then people will need to solve it, right? And what does that look like, given the constraints that we have on our time, given the situation that we find ourselves in? I’ve had sort of some revolutionary leanings in my politics for a long time. You talked in my intro about how I grew up in Seattle in the post WTO, and there was this understanding in the communities that I came of age, and politically looking at, for example, the Zapatistas and all kinds of different revolutionary and people’s movements around the world. Sometimes the movements have to be forceful, sometimes they have to use violence, or what people would term as violence. I don’t consider economic sabotage to necessarily be violence, although, of course, look at economic sanctions against Iraq, for example, which killed a million civilians, that’s more devastating than than any war can be. But I think that we need to be clear eyed about these things.

I say this as somebody whose grandfather was a conscientious objector who refused to fight in World War II. So many people look at World War II and talk about it as being that just war, and the Americans fighting the Nazis and the Italian fascists and the Japanese fascist state. The reality, I think as a lot of people know, anyone who’s read, for example, “A People’s History of the United States” knows that the US government didn’t go into the Second World War with altruistic motivations. The motivations were imperialist, they were economic. And many people in the government and prominent members of our society supported the Nazi regime from the very beginning. One of the biggest examples being Henry Ford. IBM, of course, worked closely with the Nazis. We all know that. This is sort of beside the point. But I say this as somebody, again, whose grandfather was a conscientious objector. I came of age politically in the anti-war movement, trying to stop the invasions of Afghanistan and then Iraq. So I’m not somebody who loves violence. I’m not somebody who wants to go out and cause destruction and impose my will on other people. That’s not my ideology. I’m somebody who values peace and basically wants to just have a good quiet life, live it in a good way and have good relationships with the people around me. And I would be very content if I could just go live in the woods for the rest of my life with my loved ones and not have very much happen. That sounds great to me. But unfortunately, we’re living in this global crisis and we need to come up with some sort of response to it. And all of the things that I look at, the government’s solutions, the corporate solutions, the greenwashing, all this stuff around alternative energy and green technology, the Green New Deal, all of these things. I look at them and they seem vastly disproportionate to the scale of the problems that we face. We need fundamental economic and political change across the whole planet. I don’t think that that is going to happen simply or easily. And frankly, I don’t think that’s going to happen willingly. I don’t think people are willingly going to give up this life.

You know, my nephew, who’s two and a half years old, and I’m hanging out with him recently and reading books and so on, and like most kids, he’s really into trucks, he’s really into the garbage trucks and the cranes and construction sites. It’s fascinating to him. It was fascinating to me when I was his age. And I was writing last night about the sadness, the tragedy that this kid, growing up in an urban area, is not going to be exposed to grizzly bears, to orca whales, to wolf packs. You know, the megafauna of the past have been replaced by what I’m calling in this article I’m working on a mechafauna. Large machines have replaced large animals. And instead of navigating through a landscape of raging rivers and towering mountains and glaciers, we’re navigating through a landscape of towering skyscrapers and freeways and businesses. So, most people are profoundly disconnected from the natural world. And I think because of that, we have all been inculcated into this ideology that looks at civilization and this way of life as… It’s even beyond a good thing, it’s something that’s so fundamental that it cannot be questioned.

Most people literally cannot imagine living a different way of life than the modern industrial, high energy way of life. Most people, at least in the United States where I live, can’t imagine that. Some can, some people obviously have more experience living off the land or living in communities and in more intentional ways and can really imagine a much lower energy, a smaller scale, more localized way of life, which is the only sustainable path for the future. But politically, if we think that that way of life, moving everyone on the planet away from high energy ways of life and dismantling those high energy systems, that’s the only path towards survival we have as a species. And that’s the only way to stop the mass destruction that the dominant culture is perpetuating. And I don’t see that happening willingly. There’s just no signs that that’s going to happen, at least on a large enough scale, on a fast enough timeline.

Sam Mitchell: What was your phrase you mentioned five minutes ago? The disproportionate scale of the response to the level of the crisis. The problem, the predicament. And again, I’m just going to play devil’s advocate here. So, assuming that I agree with everything you say, that what we need to do is target key nodes of global industrial infrastructure, such as shipping, communication, finance, energy, and destroy them with a goal of inciting cascading systems failure. The problem that I would have with that, on the assumption that I agree that was a noble goal, and I’m not saying whether I do or not, my problem, Max, would be the same problem I have with all of the other responses you mentioned, that there is no way in hell that we’re going to marshal the forces necessary. It’s not it’s not even David versus Goliath at this point. Rather, it’s a goldfish vs. a blue whale. What would you say to get me on your team? Assuming as that I agree I’m going to join your team, but this is the reason I’m reluctant to. What would be your response to me?

Max Wilbert: Well, the first thing I would say is if we don’t try, then we’ll never know whether it was possible. I mean, people have achieved plenty of incredible things throughout the history of the world, both for good and bad, that seemed incredibly unlikely in the beginning. And there’s one quote that I like to spread around, it was from Michael McFaul I believe, who is on the National Security Council. And he said “every revolution seems impossible beforehand and inevitable afterwards”. So I don’t think what you just said is a unique feeling. I think, millions of people have felt that way throughout history in all kinds of different difficult and dangerous political situations. And yet people still choose to fight. People still choose to organize. And of course, not everyone does. I don’t expect everyone to join a movement like what I’m talking about. But, we need to find those people who are willing to join, are willing to fight. And, that not only means people doing that work, fighting for that cascading system’s failure, going underground and taking serious action. I think it also means people who are just willing to speak up and talk about this openly, because I don’t think this is anything to be ashamed of, or anything that needs to be discussed in the shadows. You know, I’m willing to go on national television and talk about this. I don’t care because we’re in a desperate situation. And this to me is not any less mainstream. I mean, look at the politicians that you see on TV and these debates around the U.S. presidential election and so on. The stuff they’re talking about is completely out of touch, in most cases, with the realities of what we’re facing. And I look at those people as the extremists. I look at those people as the the people who are insane and out of touch with what’s actually happening in the world. So, I think we need people involved in all kinds of different levels.

And people hear what I’m saying and get scared. You know, this is serious stuff. Obviously I’m talking about revolutionary politics really in a sense, and that is a dangerous thing. It’s dangerous now and it has always been dangerous. And I think one thing that people neglect is the fact that revolutionary movements involve people at all kinds of different levels. I mean, there are people who are part of deep green resistance, the group that I’m in, who are parents of young children, who don’t have any time, who don’t have the ability to be a public face for the movement. People find ways to contribute. You know, people volunteer in all kinds of different ways. People translate articles. People donate. People do all kinds of different things to build a culture of resistance to support these ideas and build them up into a political force, a political movement that can actually influence the course of events. So that’s what we’re trying to do.

And I understand people’s feelings of disempowerment. You look at mass media, you look at the culture that we live in, and that’s one of the main goals of this system, to keep everyone in a position of feeling disempowered, of feeling a sense of total alienation, of feeling disconnection. And one of my experiences in political organizing and doing this work is that not only do I feel like I’m doing the right thing, but, I find this work to be incredibly fulfilling, personally. I find myself with a sense of purpose that didn’t exist before I found these ideas. When I was younger, I felt very swept along in global events. And now I feel like I’m part of an organized force that’s working to change things. And the fact that we are outnumbered and outgunned and have no money and so on, all of these things are realities that many other people throughout history have faced. So, I look at myself and other people in this movement as part of a multi generational struggle, that has frankly been going on for thousands of years against the culture of empire. We need to step up and step into that role. And I think it takes a lot of wisdom and it takes a lot of commitment and it takes a lot of self work to confront those fears, to have real conversations with yourself and your loved ones about what this could mean. And it takes courage. I would rather do this work than sit on a couch and watch Netflix for the rest of my life. So it does that make me crazy? Maybe in the minds of some people in this culture, but I would rather be crazy than working 40 hours a week, slaving away at some job I hate, getting ready to retire into a climate nightmare and leaving nothing, leaving nothing for future generations.

Sam Mitchell: OK, well, there are so many things I was trying to grab hold of out of that response. One word stands out to me and that response, it was outgunned. Max has a fine YouTube channel himself. You can find Max’s YouTube channel, and I’ve noticed that the other YouTube bots have not shut you down. I’m a little bit surprised that you are openly advocating on your YouTube channel to start picking up guns. Talk about that, where literally does arming ourselves fit into your program? I mean, guns have bullets. Where are you talking about those bullets ending up?

Max Wilbert: Well, to be clear: The strategy that you talked about, the Decisive Ecological Warfare strategy, is explicitly designed to minimize civilian casualties. That’s something that has been a part of our ethic from the beginning. We’re not talking about waging open warfare on governments or the industrial system. We’re talking about sabotage. We’re talking about coordinated economic sabotage. Now, I’m not naive enough to say that that may not involve some violence against people, but that’s not a call for me to make because I’m not directly involved in that process.

We talk very clearly about the need for a firewall between people who are above ground and advocating these things, like myself, and people who go underground to actually take those type of actions.

So I can’t actually tell those people what to do, and I don’t know what they will do or what they are doing if they exist. So, in some ways the point is moot. You talked about my YouTube channel and I’ve made some videos, like you said, talking about weapons. And I see two main reasons for this.

The first is self-defense. I think that we’re entering a world that’s getting increasingly chaotic. And people like myself, who advocate for what is seen as radical politics in this culture are at risk, compared to a lot of other people. I receive death threats regularly, I receive all kinds of hateful messages from all kinds of different people. I’ve been doing this for a while, and that has been happening consistently. And it’s only speeding up. We’re seeing increased polarization all around the world. We’re seeing the increased rise of of right wing, ultra nationalist and proto-fascist movement.

And that’s something to be concerned about. That’s a real concern. And I don’t think the police or the state are ever going to protect people like me, or even people who aren’t revolutionaries. Just look at the black community in the United States and all the violence that they have been facing for so long, at the hands of the police and racist vigilantes. I think we need to learn to defend ourselves, and that doesn’t mean we love guns or we build a stupid gun worshiping culture like the NRA.

I think that means that we be adults, and we make reasonable decisions to preserve the safety of ourselves and our communities. And I think as climate crisis intensifies, we’re going to see more and more instability and the potential for violence.

So I want to see communities of resistance, and especially communities that are engaging in on the ground work, defending the land, and building alternative communities, building alternative economies and ways to survive. I want to see those communities making serious decisions about what they’re gonna do, because if you have a great, wonderful, groovy eco village, and some sort of climate disaster knocks out the local government, then you may have to be prepared for a bad situation.

One of my friends is from Pakistan, and she talks about that we should look towards Pakistan as an example of what the U.S. and other more “wealthy” first world nations are moving towards in the future. You’re seeing a lot of conflict, you’re seeing a lot of sectarianism, violence, blackouts and rolling brownouts. Power is only available for certain periods of the day. A lot of desertification, a lot of extreme poverty contrasted with extreme wealth. And I think that’s the future we’re in for. Rebecca Solnit wrote a book about natural disasters, and about how people have this idea that when disaster strikes, everyone becomes rapists and looters and things get really nasty and really bad really quickly. And she writes that’s actually not what happens. That’s much more the exception than the rule. In general, when disaster strikes, people tend to come together and work together and cooperate and help one another. I’m not somebody who looks at human beings as inherently evil and nasty, and it’s gonna get really bad and brutish. But for political organizers, for people who are specifically resisting civilization, capitalism, white supremacy and so on, I think it makes sense to reasonably know how to use and own firearms legally.

The second reason that I talk about is almost, in a sense, more philosophical. In the Second Amendment of the US Constitution was written specifically: In a situation where people rose up to fight against a government, and they use the weapons that they own to do that. And then they wrote into the Constitution protections for people owning weapons. Obviously, the American Revolution was a bourgeois revolution. It was a high class revolution, a ruling class revolution. It was not a grassroots people’s movement, it was not a movement for freedom or progressive ideals. But nonetheless, I think it’s true that preserving independence from the state is incredibly important. And I find it very hypocritical that many people on the left, for example, will critique the administration for building concentration camps and for police brutality and violence, and then will turn around and the same time advocate for taking away people’s weapons, taking away weapons of the public. And of course, mass shootings and all these different issues, there are very serious issues and they are real issues. And at the same time, I think that preserving a population that is armed is a bulwark against tyranny in some ways.

The other part of it is, you look at the United States and there are a huge number of guns in private hands in this country, and the vast, vast majority of them are owned by conservative and far right people. Not many are owned by people with progressive values, who really value ecology and really value feminism and really value anti-racistm. I’m not saying that all conservatives are racist or whatever. That’s an oversimplification. But I think the fact is true, that all the weapons concentrated in the hands of the right is not good. And I think, as we see increasing instability, it makes sense to know how to use weapons. And again, that doesn’t mean you glamorize them. That doesn’t mean you worship them. And that doesn’t mean that you plan some sort of armed attack against whatever. That’s not what I’m talking about. But I do think that thinking about weapons and knowing how to use them can help move people on the left towards a greater sense of seriousness and a greater sense of power. I didn’t grow up in a gun culture at all, I didn’t shoot a gun until I was 21 years old, something like that. I wouldn’t consider myself a gun nut or anything along those lines. I don’t really enjoy shooting guns at all, although I do practice it occasionally and I do hunt, because I like to connect with the land and get my own food and get the best quality possible meat that’s local and organic and has no chemicals in it and was grown on the mountainside, not in some factory farm.

But I think when you critique the power of empire, when you critique U.S. imperialism, when you critique police brutality and you have never touched or fired a weapon, then I think that you perhaps have a skewed understanding or an incomplete understanding of what you’re talking about. And I think this can lead to some dangerous ideas. Many progressive people, leftists and people in the hippie community talk about things like violence doesn’t work, violence never works, which I think is just a stupid idea, frankly, I think the reality is that unfortunately, violence works really well. That’s why the US military uses it. That’s why the police use it. That’s why abusers and wife beaters use it, because it is very effective. And that’s not a good thing. But again, I think we need to be adults and face these realities.

Sam Mitchell: Yeah, well, I know that you of all people are keeping up with the trends, the skyrocketing number of environmental defenders being just flat out murdered by these guys. When I was reading something in the past few months, about one of these tribes in Brazil, these warriors, you know, and actually they need to be defending their land base. I am 100 percent in support of an Amazon indigenous person using violence to defend their land base and their culture. But at the same time, Max, I’m thinking in the back of my head, there is nothing that this Bozo Nero guy, as I call him, there is nothing that Bozo Nero would love more than an Amazon Indian to put an arrow through the throat of a soy farmer or a or a gold miner or someone building a hydro power dam. Are you following me? Then you would see what violence would look like. It would be a bloodbath. And they would say, well, they threw the first punch. That this guy with his bow and arrow killed some guy building a riot rod, driving a bulldozer or building a hydroelectric dam. Do you see where I’m going with this? And I would be cheering the guy with a bow and arrow, but I know what it would turn into, brother. What do you think about that?

Max Wilbert: Well, I think you’re absolutely right. And that’s why I think we can’t get caught up in dogma. I’m not a dogmatic pacifist. I’m also not a dogmatic advocate of violence. I think you need to be situational in the methods that you choose to use to achieve a certain goal. And if you are trying to defend your land, then in many contexts the best way to do that is going to be completely nonviolently. And that’s not a problem for me at all. I’ve participated in countless nonviolent actions and direct action blockades and protests and media events and all kinds of stuff on that spectrum. So, I don’t think that’s a contradiction at all. I think we need to be flexible in the way that we approach these things. But I also think that we need to avoid blaming the victim. And I think we need to recognize that of course what you’re saying is true, that the state will use violence as an excuse whenever it can. The reality is the states can be violent no matter what. The corporations are going to be violent no matter what. Their violence may take different forms depending on the situation, but their modus operandi is violent and whether they are sending in the military or whether they are using international trade agreements and unfair loaning practices. From organizations like the WTO and the World Bank, that force massive infrastructure projects on poor indigenous people and rural people all over the world, or whether we’re talking about banks here in this country and how they function and how they keep the poor poor and exploit people. They are using violence every single day. That is their main tool. And so our choice should not be some moral abstraction – not that morality is abstract – but I think that we need to be looking at what methods are going to be effective to stop them, and not artificially constraining ourselves based on morality. Morality that frankly I think we’ve been taught often. I think there’s a reality that we’re taught, Martin Luther King in schools and we’re not really taught about Malcolm X, and we’re not really taught about the Black Panthers, and we’re not really taught about revolutionary movements around the world, except for, again, the bourgeois American Revolution. And we have all internalized that training. Again, I think there’s a reason that we’re taught so heavily about figures like MLK and Gandhi, and even a figure like Nelson Mandela, who is lionized in the United States and looked at as this amazing figure. Well, very, very few people recognize that he was the leader of an underground military organization that was attacking and assassinating people in the apartheid government, in the apartheid state, and was coordinating sabotage, attacks against the electrical grid, against diamond mines, against power stations. And that side of the apartheid resistance has been completely whitewashed. And instead, we’re talking about Desmond Tutu and nonviolent protest and truth and reconciliation. The reality is that social change and revolutionary change throughout history has always been a messy process with a lot of different pieces and a lot of different people working in different ways. I don’t think that that means that you have to be opposed just because you’re using different tactics. And I think that ideally, the strongest movements do use all kinds of different methods and all kinds of different tactics across the spectrum, and they’re coordinated and they support one another. They’re not going to condemn one another for for using different methods. They’re going to just work in the most effective way that they can.

Sam Mitchell: I would add that they’re very savvy. We’re still on the first paragraph, and I made it exactly one paragraph into this whole list of quotes of yours. I wanted you to expand. So I’m just going to leave my notes behind then.

OK. You mentioned somewhere in the past 10 minutes and you’ve written about this, about whether humans are inherently … you know, I just interviewed this ecologist named William Reas. He should probably go listen to that interview, it was a last one of twenty nineteen. He is based from an ecological perspective, if not from a moral one, saying that humans are a plague on this planet.

I want to draw and find out where your line is. I don’t know whether you’re speaking for Deep Green Resistance, I just want to hear your own line.

I want to make clear that I understand that you draw a big line between global industrial capitalism, civilization, that whole messy thing, and humanity as a species. That you put those in kind of two separate camps. Well, I think a lot of people listening to this podcast probably agree with you 100 percent on that the global industrial civilization is the worst reflection of humanity, and we can all agree it needs to go, at least the people down in this rabbit hole.

But some people would say that even that’s not going far enough, that humans just need to go. What is your comment to the people saying that ending global capitalism still is not enough to save the planet, and we just need to have humans say bye bye and disappear?

Max Wilbert: Well, I think that’s a profoundly civilized thing to say. I think that’s only something that you can say if you grew up in a culture that is destroying the planet, which not every culture has done. You know, I grew up in a culture that’s destroying the planet. I grew up in a city, and grew up with cars and everything. So I can certainly understand the impulse and why people feel that way. But the thing is, people who are saying that are looking at history and interpreting it in a certain way. And the reality is, you can look at the same history and interpret it in a different way, or you can talk to people and look at situations where people are actually living in land based communities and see what’s happening ecologically, see what’s happening to the people. So, there are thousands of examples of cultures that have lived more or less in a balance, over the long term, with the natural world. And I think that this is actually an adaptive trait for human beings, to live in sustainable ways. And I think, for that reason, we are sort of born naturalists.

If humans are just given a little bit of training and a little bit of education and encouragement to learn about the local ecology, and immerse themselves, and exist within a living ecology, then I think that we can do it extremely well. That’s not to say that human beings don’t influence what’s happening around them in ways that could be called destructive. Quite obviously, humans are an apex predator. And apex predators always disrupt and change the world around them and always influence things, especially when they come into a new habitat for the first time. They’re going to upend things. They’re going to make a lot of changes. But that’s no different than if you don’t have wolves in an area, and then they’ll show up. They’re going to cause very similar changes to the ecology on a large scale. Nobody is saying that wolves are inherently destructive, right? I think humans are no different. For example, people look at the wave of extinctions that has followed with some species when indigenous peoples first showed up in certain areas, for example some of the Polynesian cultures, when people first showed up in North America… There is debate about these issues and they’re not well understood, because obviously we’re talking about ancient history. We’re talking about very limited records from archeology here. So we’re just interpreting the past, right? And that’s very limited. But what it appears like happened in these situations is that humans – again, an apex predator – showed up in an area, they caused a lot of change, they may have caused a few extinctions, and then things settled down. People figured out how to live in that area in a way that was balanced, and things more or less stayed the same for thousands of years after that. That is sustainability, and that’s an adaptive trait for human beings. And I think that, again, if you have not lived in that way, then it’s hard to perceive how that can happen. When you have grown up in a completely growth based culture, in a Judeo-Christian, Abrahamic religion, a world view of growth and patriarchy and as many children as possible and no relationship to the local ecology, then you’re going to look at that with skepticism. But the reality is that our natural state is an animistic state, where we are in real everyday relationship with the natural world around us, and we develop individual personalized relationships with certain places, a certain creek, a certain river, a certain forest, a certain herd of deer, a certain population of salmon, a certain family of grizzly bears, and we learned their habits and their ways, and we watched them not just for days or hours, but for years and generations. And we tell stories about them and we communicate about them with each other. We pass information down over time, and we develop ways to live, while not destroying these beings who are around us, who we love. That is so alien to most people in this culture today. Most people literally cannot comprehend that, because of the human supremacism that we’re inculcated with from birth. It seems completely unthinkable. So I would disagree that humans are inherently destructive. I think that is completely wrong. We can be incredibly destructive, but I think that essentially, when it comes to the nature versus nurture argument on this, it’s all about nurture. Humans are a very flexible species, and when we are raised in a destructive civilization that has no respect for the natural world and has this growth imperative, then things are going to go downhill fast. And that’s not just modern culture. That’s the story of the last 10,000 years, that’s civilization as a whole.

Going back to the Fertile Crescent, the so-called Fertile Crescent, that’s no longer fertile anymore because – I think Derrick said this on your show – the first written story of civilization is about Gilgamesh cutting down the forest, to build a city and to build an empire, an army and to become wealthy and powerful. That is the first written story of civilization. That’s the first written story. Civilization had existed for quite a while before this. This story was written from what we understand. And archeology tells us that indigenous peoples, people living outside of civilization, people living outside of mass mono crop agriculture, lived in balance for hundreds of thousands of years around the world, before civilization came. And when that transition to civilization happened, then you start seeing massive destruction. So, for example, global warming. A lot of people think it began with the industrial revolution and with the burning of coal and steam engines and so on.

That’s not actually true. Global warming actually began with civilization and the beginnings of widespread agriculture. For example, if you look in the ice core data, I think about thirty eight hundred years ago – something in that range, don’t quote me on that number – you see a big spike in methane emissions, and that corresponds with the beginning of rice paddy agriculture in Southeast Asia. There is a climate scientist named William Ruddiman, who argues and demonstrates from the data that the amount of greenhouse gases released by agriculture, and the destruction of habitat through the rise of civilization, the amount of carbon released is roughly equivalent to everything that has been released during the entire industrial period. It just happened over 10,000 years instead of over two hundred and fifty years. So these problems are not new. And for that reason, I think it’s easy for people to look back at ten thousand years of history and say, look at how destructive we’ve been. But the point is, you have to go outside history. You have to go into pre-history, because these indigenous communities, before civilization, did not have written records. And indigenous cultures, today and during the last 10,000 years, that have existed and have remained intact, have lived in profoundly different ways.

This isn’t to lionize or sort of falsely idolize indigenous peoples, because I think a lot of indigenous communities can be critiqued on all kinds of different issues. We all have disagreements about the best way to live, and not all communities that people call indigenous live sustainably or have lived sustainably at all times. I think that’s, of course, a vast oversimplification. We’re talking about thousands of cultures over thousands of years of history. We we can make some broad generalizations, but it’s dangerous to say that it’s always this way. You know what I mean?

Sam Mitchell: One of the things that I found missing in your work, you do not seem to talk about the issue of overpopulation very much. And I just want to say, sure, I know that you understand, if global industrial civilization comes down, that is going to mean the population of this planet is going to come down with it. Is that a good thing? A bad thing? Have you ever thought about what a sustainable human population living in balance with nature looks like on planet Earth?

Max Wilbert: Of course, that’s a huge issue, and I thought about it a lot. In terms of your last question, don’t have a number and I don’t think I could. That’s not something that I can dictate, it’s something that obviously will change, depending on the ecological circumstances that people find themselves in. I think the leading writer on this topic was William Catton, whose book “Overshoot” is one of the most important books that’s ever been written.

Sam Mitchell: Derrick Jensen’s “Endgame” and William Catton’s “Overshoot”, those are the ones I put at the top of my list.

This house of cards is coming down, you and I both know that, Max, whether we bring it down or it comes down itself. Do you believe that we’re going to be living on a planet of 10 billion people in 40, 50 years from now, or is that number going to be a whole hell of a lot less?

Max Wilbert: Well, that’s actually an interesting question. I think I may actually differ from a lot of the collapse people on this, because I don’t actually think that collapse of this culture is a given in the short term, and that sort of timeframe. I don’t think that’s a given. I think it could happen, but it does not seem faded at all to me. And I say that as somebody who traveled to the Arctic in a climate science expedition and has walked on thawing permafrost. I’m very familiar with all the feedback loops and the methane burp potential, and all these different issues. We don’t know what’s happening. We don’t know how fast these changes are gonna happen. But I think, this culture continuing to sail along and grow and grow and grow is the worst possible outcome.

And I think that even if nothing changes and nothing gets worse, we are already have enough reason to resist now. I don’t know what the future is going to look like. And I think that you are right, that the human population is not sustainable and it’s going to be lower at some point in the future. And there are a lot of ways that that could play out. It could be really bad, and just a ton of people all die very violent, horrible deaths. Or it could be achieved in a sort of more planned, humane way, by simply reducing the birth rate and letting natural deaths reduce population. Maybe the reality or how it will play out will be somewhere in the middle. I don’t know. But this issue is one of the reasons why I think feminism is such an important topic, because I think that the whole issue of overpopulation is incredibly tied up with agriculture and with patriarchy. And I would say the most important writer on this topic is Lierre Keith with her book “The Vegetarian Myth”. It’s sort of focused around the idea of diet, but it’s really about patriarchy and agriculture and civilization.

She points out rightly that within agriculture, within civilization, maximizing the number of births is the best way to increase growth. That’s the best way to make workers available for the workforce, to work in the fields, in the factories and to serve in the army. And the coordinated culture of control and domination, male domination, that is patriarchy, is something that has existed for a long time at this point.

All around the world, when you have examples of women actually gaining some level of political control and autonomy and pushing back the powers of the Abrahamic religions and pushing back the powers of patriarchal society, you see birthrates just plummet. The human population is unsustainable and it’s going to be lower, and I would prefer that to happen in a way as humane as possible.

Sam Mitchell: And I really hate to break in here, brother, but I am glad to say I’m going to be interviewing Lierre in a few weeks. I guess I’ll pick up with her on the book Bright Green Lies, since we did not have time to get to, we’re going to collapse here in a few minutes.

So Max Wilbert, if you’ve ever heard one of my interviews, you know how I always end them:

If you where not speaking with Sam Mitchell at Collapse Chronicles, where you had free reign for an hour, but you actually have the mainstream media with a microphone in your face saying “Max Wilbert, give us your 60 second sound bite to humanity and the opening bell of 2020”, what would those 60 seconds sound like?

Max Wilbert: Well, the problems that we’re facing are massive, and the political systems incapable of addressing them. So many of the solutions that we’re seeing, such as green energy, are turning out to be false solutions. We’re seeing a huge explosion in green technology and yet at the same time, emissions continue to climb and pollution continues to climb. So what do you do with that? I think we need fundamental change. We need broad economic change. And I think that looks like a complete restructuring of the global economy. How this could happen?

There are many different ways, and I want to support people who are working for these type of goals, working for deep growth, working for relocalization, working for permaculture. I want to support people who are working in all kinds of different ways. For myself, I have chosen a revolutionary path because I think that not only do we need to build up those alternatives, but I think we need to be prepared to dismantle the dominant systems of power that are destroying the planet. I don’t think they’re going to stop willingly. So, I would invite people who are interested in learning more about that or getting involved in that to reach out to me. Let’s get connected, so you can become part of this culture of resistance, because it’s our only chance. And I think that we are the inheritors of a beautiful tradition and we are living in perhaps the most important moment in the history of the human species. And what happens in the future is completely dependent on what we do now.

Sam Mitchell: Okay. And with that, Max Wilbert, we’re gonna have to wrap it up. Max Wilbert, thank you very much for taking an hour out of your schedule to come talk to us on collapsible chronicles, but more importantly, thank you for your work and keep up the good fight.

by DGR News Service | Jan 31, 2020 | Colonialism & Conquest, Direct Action, Human Supremacy, Listening to the Land, Rape Culture, Women & Radical Feminism

By Rebecca Wildbear

Cottonwood trees shaded the little river, while the rising sun brightened the blue sky and lit up the expansive slopes of the Sonoran Desert, dotted with prickly pear, saguaro, and cholla cactuses. I was in Aravaipa Canyon, a gorge in the Pinal Mountains of Southern Arizona, where I would prepare thirteen people to be in ceremonial conversation with the land for three days and nights. Aravaipa is an Apache name which means “laughing waters,” and the name fits. The river was brisk and clear as it churned its way around boulders and rippled over gravel bars in a playful, bubbling chorus.

On that first morning in the desert, I’d awakened with a dream.

I see a woman about to be raped. She’s yanked out of the driver’s seat of her car by a man who holds her captive while undoing his pants. A male friend turns to me and asks if he should try to stop it.

“Yes, absolutely!” I respond in haste.

My friend picks up a club that resembles a baseball bat and moves toward the rapist. My stomach knots; what if I’ve just sent my friend into a dangerous situation and he gets killed or hurt? I decide to join him and approach the rapist from behind, while my friend approaches him from the side. As we get closer, the rapist stops, and I feel surprised when he turns around with his hands held up in surrender.

Although our dominant culture marginalizes dreams, we must learn to pay attention to the wisdom and direction they offer. The Tz’utujil Mayan culture elected officials based on the number of villagers who dreamed of that person occupying the position.[1] The dreamwork of the Iroquois preceded the dreamwork of Freud and Jung. The Iroquois knew dreams were sacred and that to ignore them was to invite disaster;[2] they understood that the human soul makes its desires known through dreams.[3] Founder of Dream Tending, Stephen Aizenstat says dreams arise from the “World Dream;” they offer us a glimpse of the desires of the world so we may “act in the world, on behalf of the world…in Archetypal Activism.”[4] When the wisdom of our dreams guides our direct action, we’re able to bring together our visionary and revolutionary natures in a radical dreamwork. With the earth dreaming through us, we’re guided to take the actions that matter most.

Dreams hold a multiplicity of meaning and, like trees, rivers, and birds, each dream element has intelligence; it usually understands more than our waking ego. I guide others to recount their dreams in present tense, inviting them to be in the dream so its visceral impact has an opportunity to arise or burst forth.

On that morning in Aravaipa Canyon, I closed my eyes, returning to the dream about the rape. What was it asking me to experience and how could I steep myself in its mystery? The edgiest part of my dream was asking my friend to risk his life. I felt afraid that he could get hurt or die. I feel similarly when I send questers on a 3-day solo fast. Although I’ve taught them ways to be safe in the backcountry, anything could happen.

On a vision quest, each quester is invited to let go of their identity and listen for a deeper call—in this way, we discover who we really are and how we may serve the world. Questers are invited to undertake a psycho-spiritual death, an initiatory dismemberment, which can lead to a mature adulthood. Such a journey is inherently risky, even beyond the solo days.

Founder of Animas Valley Institute, Bill Plotkin writes that the great crises of our time stem from breakdowns in natural human development. He says that healthy, mature cultures have always emerged from nature: “from the depths of our individual and collective psyches, from the Earth’s imagination acting through us, from the mythic realm of dreams or the Dreamtime, from Soul, from the Soul of the world, from Mystery.” We can’t think our way into maturity; we cultivate our wholeness through allowing the natural world and our dreams to guide us.[5] Yet we can only become whole within a healthy Earth community. So what about the clear-cut forests, drained wetlands, and plowed prairies?

As mountains are mined, rivers are dammed and poisoned, and hundreds more species become extinct each day, my heart breaks at our human failure to protect our nonhuman relatives on whom we depend; they’re dying because they depend on us too. As the oceans fill with plastic, the ice melts, and greenhouse gas emissions grow higher each year, I feel the rape of the Earth alive in my body and psyche. Perhaps this dream invites me beyond myself. What if this dream is asking me to seek assistance in stopping the rape of Earth?

Rape is Acceptable

I had a lot of dreams about rape in my early thirties; it felt unstoppable. How surprising that this dream ends with my friend and I stopping the rape.

I remember guiding women survivors of violence on Women of Courage Outward Bound courses in my twenties. We’d listen to the women’s stories, the other two female guides and I, and then one night, to our surprise, we shared our stories in hushed voices, confessing that we too were survivors. The line between heroine and victim, wilderness guide and survivor, blurred.

It’s hard to perceive rape when you’re raised in a culture where rape is acceptable. As the most under-reported crime, rape[6] is notoriously under-investigated, largely unpunished, and rarely spoken about; less than one percent of rapes end in a felony conviction. Even then, a perpetrator does not often receive jail time, especially if they knew their victim; this sends a message that it’s acceptable to rape someone you know.[7] In eight out of ten cases of rape, the victim knew the person who sexually assaulted them,[8] and ninety-three percent of perpetrators of child sexual abuse are known to the victim.[9] Our culture barely acknowledges rape happens and nearly condones it. The rape of women, the abuse of children, and the destruction of land is our norm.[10]

Sister Carl, my junior high school teacher, repeated daily: “Silence gives consent, girls.” Perhaps she was trying to help us avoid some trauma she’d suffered. But what did the boys in the room hear? What if there wasn’t an opportunity to speak, or we were too young to understand? And what of the Earth? If we are deaf and dumb to her language, does our lack of hearing exempt us from the harm we cause? Perhaps the memory of Sister Carl’s words is echoed in the message of this dream: speak, act, stop the rape.

Rape is Legal

American law is orchestrated to protect abusers,[11] and it legalizes the right to exploit land and water, while simultaneously making it illegal to protect them. “Sustainability itself has been rendered illegal under our system of law,” said Thomas Linzey, Executive Director of the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund.[12] Our dominant culture, global industrial empire, does not acknowledge the rape of the Earth. Instead, it talks about acquiring resources and the right to exploit. While the Earth suffers massive environmental devastation, many call it climate change and focus on human survival, but dealing with climate change within the values of our dominant culture will only allow the rape to continue.[13]

Our ecological crisis is sourced in a “collective perceptual disorder,”[14] a “collective myopia”[15] that misses our innate connection to Earth. Our culture is founded on the misperception that nonhumans aren’t alive and have no feelings or consciousness; this allows us to perpetuate the lie that no rape is happening at all. To stop a rape, we have to perceive that one is happening, and to do that, we must recognize that we live embedded in relationship with all of life on the planet.

How will I ask people to help me stop the rape if they don’t see it? Dissociation, denial, and silencing perpetuate trauma; to heal, the truth must be told. Although the “ordinary response to atrocities is to banish them from consciousness,” remembering terrible events is part of restoring justice.[16]

How would you respond if someone you love was threatened? When we see our earthly relatives being harmed, aren’t we equally responsible to act fiercely and lovingly to protect them, like a mother grizzly looking out for her cubs? Fighting back isn’t wrong; it’s relative to the situation in which we find ourselves. It is just as wrong and harmful “to not fight back when one should as it is to fight when one should not.”[17]

The Love of Trees

I know how it feels when others don’t see the rape. My neighbor friend and I were four years old when we had our first sleepover. When I returned the next day, sick with a fever of 103, no one guessed that my neighbor’s father, Jack, might have hurt me, even though his wife sometimes came over to our home when he was drunk to avoid being hit. No one found it odd when I said my vagina hurt and suddenly refused to attend nursery school. I screamed and cried until I was allowed to stay home. No one wondered why my friend, Jack’s daughter, was so troubled. I still remember when she stabbed me in the belly button with a needle. After playing with her, I often returned home with bite marks and bruises up and down my arms.

When I kept insisting that my vagina hurt, my mom took me to the doctor. She stayed in the room while the white-haired man examined me. I asked her later what he had said, and she told me that he said I needed to use less soap.

Being told everything was fine was confusing when my body knew a different truth—one that my mind didn’t know how to hold, let alone put into words. Although in the dream my friend could see the rape, no one saw it when I was four.

But I wasn’t alone; I lived in trees. The thick, ancient trunk of a giant ash tree that rose well over 100 feet in my backyard was the center of my world. Down the hill in a grove of pines, I played in needles, sometimes climbing to the tippy top, arms and body wrapped around the thin tip, the weight of my body gently swaying from side to side. In summer, I crawled to the far reaches of the cherry tree’s branches, eating more berries than made it into my basket for mom’s cherry pie. The maple tree grew in the front yard; I went there to hide, high behind walls of green leaves, where I could see all and no one could find me.

I sensed the trees had feelings, lives; they were living beings with whom to be in relationship. Did the trees know my secret? Is that, in part, why it felt like they looked after me? All trees know rape; ninety-seven percent of North America’s native forests have been cut down.[18] I didn’t know why my young body returned again and again to be held in the branches of these elders who surrounded my suburban home. Or why I turned to the smell of pine and bark instead of human skin or voice when I hurt. Now, I imagine that something in my cells trusted their love and wisdom; they nurtured me.

The Rape of Earth

The Apache who named Aravaipa Canyon no longer live here. Sitting at the edge of the river, I marvel at the joyful laughter of its flowing waters. During the 19th century, the Aravaipa band of Apaches living here fought many battles with the U.S. Cavalry. Hispanic and Anglo settlers began grazing stock and developing copper mines in the watershed. In the infamous Camp Grant Massacre, a death squad of American pioneers—including Tohono O’odham Indians, as well as Mexican Americans and Anglo-Americans from Tucson—descended upon an Apache camp before dawn on April 28, 1871. Those sleeping were clubbed to death, while those awake were shot by men stationed in the bluffs above. [19]

Arvaipa Canyon wilderness

In less than an hour, the raiders had claimed the lives of nearly 150 Apaches, mostly women and children; the men were away hunting. With no casualties to themselves, they sold twenty-nine children into slavery in Mexico. This is neither the largest nor the most brutal of attacks on Native Americans, but it came at a time when a “peace policy” had been promised by the federal government. President Grant expressed outrage and sought to punish the attackers. Although a trial was held for 100 alleged participants, no justice was had; a jury of twelve Anglos and Mexican Americans from Tucson took only nineteen minutes to find the accused not guilty.[20] The remaining Apache were relocated to White Mountain Reservation to the northeast.[21]

The rape has been happening for the last 6,000 years as “indigenous people and their tribal societies have been targeted” by the predatory expansions of civilization.[22] Species disappear by the hour.[23] Capitalism is a war against the planet—operating off the slave labor of poor people and countries, poisoning our waters, air, and lands, and destroying ecosystems through mining and agriculture. With patriarchy, “men become real men by breaking boundaries—the sexual boundaries of women and children, the cultural and political boundaries of indigenous peoples, the biological boundaries of rivers and forests, the genetic boundaries of other species, and the physical boundaries of the atom itself.”[24]

Civilization is brutal and unsustainable; agriculture is dependent upon imperialism and genocide. As feminist and environmentalist Lierre Keith said, “You pull down the forest, you plow up the prairie, you drain the wetland. Especially, you destroy the soil.”[25] Shifting from fossil fuels to green energy is a false solution. Green technology markets solutions while denuding the planet; corporations and government profit.[26] Ecosystems are devastated by solar and wind projects, and the increased mining and consumption they entail. Our political system is bankrupt, and violence against women and the Earth are “legitimated and promoted by both patriarchal religion and science” and “rooted in the eroticization of domination.”[27]

The Earth Created Us This Way

Three saguaro cactuses surrounded us in Aravaipa Canyon; each one about thirty feet tall with barrel appendages on each side that look like arms. I shared my dream with the questers in our opening council. “Will you help me stop the rape?” I said. “Put your body between the rape and the rapist?” I raised my voice, uncomfortable with the ferocity of my words. The rim across from us was some distance away, but several moving dots caught my eye. I slowly deciphered them as five bighorn sheep moving causally along the mountainside.

Harrison[28], a young man in his late twenties in graduate school, later shared his view over dinner.

“There’s not a problem,” he said. “The Earth is dreaming us; she created us this way.”

“It’s not a problem that 200 species go extinct each day?” I responded, feeling stunned.

“Extinctions have happened throughout history,” he answered. “It’s all part of her plan.”

“Extinctions have never occurred at this level. This isn’t a passive geological event, it’s extermination by capitalism,”[29] I said. “Yes, the Earth is dreaming us, but we’re sick and disconnected. This isn’t her plan.”

“We shouldn’t treat the Earth like a victim,” he responded. “She’s whole. She doesn’t need us to rescue her. She can take care of herself. She’s more powerful than we know.”

“Isn’t it possible for someone to be both whole and harmed by another?” I asked. “Life is far more complex than a drama triangle—victim, rescuer, perpetrator. This is about honoring the Earth and all of life as Sacred, regardless how powerful she is.”

“Activists are too angry, and protesting doesn’t change anything,” Harrison stated. “Tapping into the imaginative powers of Earth and soul is more powerful—shifting our consciousness.”

“Listening to dreams and perceiving our larger mythic potentialities is imperative, but so is direct action; there are forests, prairies, and animals alive today because of activists and revolutionaries,” I responded. “Perhaps it’s not either-or, but both-and. Each perspective, dream, and revolution are relevant. The mythic is happening, and the rape is happening too. It seems necessary we attend to both. Why are you opposed to seeing the rape?”

A Morsel of Empathic Resonance

While apprenticing on a women’s quest in my early thirties, I asked the dream-maker to help me remember what happened when I was four. Sleeping on the edge of a red rock cliff, I awoke to roaring thunder and the grove of ponderosa pines lit up in the lightning’s glow. Jack was in my dream. “I’m the one who abused you,” he said.

In the months that followed, I remembered the grey streak that ran through his curly black hair, and the disturbing way he looked at me in later years when we both found ourselves at the curb taking out the trash. With the support of trees and humans, my body re-experienced and integrated the memories that arose. It took years to trust what came and even longer to speak about it; it’s not a story I often share.

Those victimized in our culture are invalidated and stigmatized, but my story is only a small thread in the tapestry of violence that pervades and envelopes our culture. My trauma has gifted me with a small morsel of empathic resonance for what most other living beings on this planet endure far more often than I.

By the age of five, I wasn’t allowed to play with my neighbor; my mother had grown concerned about the reoccurring bites and bruises. The giant ash, the grove of pines, and the cherry and maple trees with whom I grew up were far less fortunate; all have since been chopped down. Although my parents had moved, I returned to pay my respects for the lives and deaths of those loving trees who raised me and were my family. I remember them often in my imagination.

The Questions of Displaced Descendants of Slaves

I remember weeping in love and loss while huddled in the crowded adobe hall with over 100 people; Martin Prechtel was sharing the rare and forgotten history of indigenous peoples worldwide. We listened to their music and heard about their creation stories, animals, and daily life. We wept over the rape, the slavery, the injustice, and so much beauty already lost. We asked questions: How did we get here from there? What birthed the original destructive culture that grew to destroy all others? How can we, the displaced descendants of slaves, live and die in a way that feeds life?

Bolad’s Kitchen is a never-before-seen school which aimed to help us remember an intact human approach to living in sacred relationship with Earth. I returned there for seventy days over four years, in my mid-thirties. Martin had grown up on a Pueblo reservation and apprenticed to a Tz’utujil shaman. He taught us an ancient economics. Fellow participants and I made beads, and later repaid our debt to the Earth for the obsidian rocks and shells we borrowed. We made pottery, moccasins, and felt, always offering the best back to the Holy Earth. She is starving and grieving, because she has not been given the ritual food and gifts she needs to live.

Martin shared stories of indigenous cultures who responded to attack in two ways. Some acted directly, fighting to protect their land, animals, and people; they were often killed or enslaved. Others acted mythically, returning to the “origination” place of their creation stories; there they waited to die intact, so their death would send out an echo that feeds all of life. But what if it isn’t either-or but both-and? What if we could act both mythically and directly? What if our revolution to stop the rape was sourced in both our ability to attune to our dreams and our willingness to resist our dominant culture?

Stopping the Rape

My dream seems to imply that we can stop the rape. I write to weave the world of dreams with direct action, so that our dreams can guide us. The weaving of mythos with revolution can support us in stopping the rape. Dreams are “willful, living beings”[30] that can re-align us with earth’s wishes. Through dream incubation, artists ask for a dream to guide their creation, and the dream that comes is “for the work of art, which uses us to birth itself.”[31] Similarly, we can invite the Earth to dream through us, and guide us toward the actions that matter most. When we act on our dreams, more dreams come to guide us further. In this way, dreams can come to guide our life. Dreams have led me to heal and discover my soul; they direct me now to guide and write; they urged me to write this piece.