by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 23, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

This is the second installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

via Deep Green Resistance UK

Before looking at nonviolence, it’s important to define what violence is, as it is often understood in varied and misleading terms. The aim of the next three posts on violence is to move away from the binary thinking of violence versus nonviolence and to appreciate the complexity of this topic.

In Endgame I: The Problem with Civilization, [1] Derrick Jensen maintains that many words and contexts are needed to approach a more complex understanding of what violence means and entails. He lists the following categories of violence in a discussion meant to provoke readers into (re)considering what forms of violence they oppose:

- unintentional and intentional violence

- unintentional but fully expected violence (when you drive you can fully expect to kill insects)

- distinction between direct violence and violence that is ordered to be done by others

- systemic (and hidden) violence

- violence by omission – by not acting leading to harm

- violence by silence – witnessing violence and not acting

- violence by lying – supporting those that carry out violence

Peter Gelderloos, author of The Failure of Nonviolence, writes critically of a typical human mindset, particularly by humans who occupy positions of institutionally maintained privilege: “If it’s done to me it’s violence. If it is done by me or for my benefit, it is justified, acceptable, or even invisible.” [2] He argues that violence doesn’t exist as an act but rather as a category; and that it is a concept regularly redefined by the state for the purpose of protecting and perpetuating systems of oppressive power. Gelderloos also asserts how common it is for people to describe things that they do not like as violent.

In Anarchy Alive! Anti-authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory, Uri Gordon suggests that “an act is violent if its recipient experiences it as an attack or as deliberate endangerment.” [3] He offers a comprehensive review of the thinking on violence in relation to activism by asking two fundamental questions: what is violence, and can violence be justified?

Gordon makes a useful distinction between the violence of the anarchist movement in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the violence of today. The political violence of past centuries often involved mass armed insurrection and the assassination of heads of state and business leaders. Today, it tends to involve non-lethal violence during protests, property destruction, and clashes with law enforcement. [4]

Gene Sharp, known as the “father of the nonviolent revolution,” argues that violence is a way to influence behavior by intimidating people. His list of what constitutes violent actions includes conventional military action, guerrilla warfare, regicide (the killing of a king), rioting, police action, private armed offensive and defence, civil war, terrorism, conventional aerial bombing, and nuclear attacks. [5]

Bill Meyers argues that the corporate state intentionally confuses language used to discuss issues of violence in order to neutralise opposition: “It is important to distinguish exactly what is meant by violence, not being violent, and the ideology of Nonviolence. Most people have a pretty clear idea of what violence is: hitting people, stabbing them, shooting them, on up to incinerating people with napalm or atomic weapons. Not being violent is simply not causing physical harm to someone. But gray areas abound. What about stabbing an animal? What about allowing someone to starve because they cannot find means to pay for food? What about coercing behavior through the threat of violence? Through the threat of losing a job? Violence as a dichotomy, with the only choices being Violence or Non-violence, is not a very useful basis for political discussion, unless you want to confuse people.”

A good place to start is the Oxford dictionary definition of violence: “behavior involving physical force intended to hurt, damage, or kill someone or something.”

In Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, Mark Boyle seriously considers if inaction can be considered violent. He asks whether there is a definition or understanding of violence that can take into account the idea of inaction, the act of witnessing gross injustice and doing nothing within one’s power to effectively combat it. [6]

Boyle argues that when asking if an action is violent or an appropriate use of force, the intention of those that carry out the action needs to be considered. He offers the example of a tooth being pulled out either as an act of care by a friend if the tooth is causing a lot of pain, or by a torturer to inflict pain.

Boyle’s ultimate definition of violence is the “unjustified use of force in ways that are intentionally or culpably injurious to another entity, or insensitive to that entity’s own needs or The Whole of which it is one part. It encompasses actions that, through willful neglect, indirect conscious complicity, or the imposition of a set of conditions, contribute to the injury of another entity.” [7]

For Pattrice Jones, both concepts and context must be considered when defining violence. When many people say “violence,” they often mean some sort of violation that involves actual or the threatening of physical force. Following this logic, both force and violation must be present for an act to be considered violence. She observes that in law there is a distinction between violence and justifiable use of force, and between violent and nonviolent crime.

With regard to context, she notes that “if we understand violence to be injurious and unjustified use of force then we can never discern whether or not an act is violent apart from its context.” Thus, there is no need to waste time arguing about abstractions; justifiable use of force isn’t violence. We can move on to consider the more important question of how much force is justifiable in defence of human and non-human life and the earth. The line between force and violence can only be determined based on the context of the situation.

Jones poses intriguing questions when contemplating the use of force in any given situation: is the action likely to result in a desired outcome; is the same outcome likely to be achieved as quickly or certainly by some other means; and is the level of force being contemplated proportional to the level of harm that is trying to be prevented? [8]

This is the second installment in a multi-part series. Browse the Protective Use of Force index to read more.

Endnotes

- Endgame Volume 1, Derrick Jensen, 2006 page 399-400

- The Failure of Nonviolence, Peter Gelderloos, 2013, page 20/21

- Anarchy Alive! Anti-authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory, Uri Gordon, 2007, page 78-95 https://libcom.org/files/anarchy_alive.pdf

- Anarchy Alive! Anti-authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory, Uri Gordon, 2007, page 79-80, read online

- Politics of Nonviolent Action, Gene Sharp, 1973, page 3

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, Mark Boyle, 2015, page 38-43

- Drinking Molotov Cocktails with Gandhi, Mark Boyle, 2015, page 45/6

- Igniting a Revolution, Steven Best, Anthony J. Nocella, 2006, page 323

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 1, 2016 | Repression at Home

by Steve Horn / Desmog

TigerSwan is one of several security firms under investigation for its work guarding the Dakota Access pipeline in North Dakota while potentially without a permit. Besides this recent work on the Standing Rock Sioux protests in North Dakota, this company has offices in Iraq and Afghanistan and is run by a special forces Army veteran.

According to a summary of the investigation, TigerSwan “is in charge of Dakota Access intelligence and supervises the overall security.”

The Morton County, North Dakota, Sheriff’s Department also recently concluded that another security company, Frost Kennels, operated in the state while unlicensed to do so and could face criminal charges. The firm’s attack dogs bit protesters at a heated Labor Day weekend protest.

Law enforcement and private security at the North Dakota pipeline protests have faced criticism for maintaining a militarized presence in the area. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and National Lawyer’s Guild have filed multiple open records requests to learn more about the extent of this militarization, and over 133,000 citizens have signed a petition calling for the U.S. Department of Justice to intervene and quell the backlash.

The Federal Aviation Administration has also implemented a no-fly zone, which bars anyone but law enforcement from flying within a 4-mile radius and 3500 feet above the ground in the protest area. Dallas Goldtooth, an organizer on the scenes in North Dakota with the Indigenous Environmental Network, said on Facebook that “DAPL private security planes and choppers were flying all day” within the designated no-fly zone.

Donnell Hushka, the designated public information officer for the North Dakota Tactical Operation Center, which is tasked with overseeing the no-fly zone, did not respond to repeated queries about designated private entities allowed to fly in no-fly zone airspace.

What is TigerSwan?

TigerSwan has offices in Iraq, Afghanistan, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, India, and Latin America and has headquarters in North Carolina. In the past year, TigerSwan won two U.S. Department of State contracts worth over $7 million to operate in Afghanistan, according to USASpending.gov.

TigerSwan, however, claims on its website that the contract is worth $25 million, and said in a press release that the State Department contract called for the company to “monitor, assess, and advise current and future nation building and stability initiatives in Afghanistan.” Since 2008, TigerSwan has won about $57.7 million worth of U.S. government contracts and subcontracts for security services.

Company founder and CEO James Reese, a veteran of the elite Army Delta Force, served as the “lead advisor for Special Operations to the Director of the CIA for planning, operations and integration for the invasion of Afghanistan and Operation Enduring Freedom” in Iraq, according to his company biography. Army Delta partakes in mostly covert and high-stakes missions and is part of the U.S. Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), the latter well known for killing Osama Bin Laden.

One of TigerSwan’s advisory board members, Charles Pittman, has direct ties to the oil and gas industry. Pittman “served as President of Amoco Egypt Oil Company, Amoco Eurasia Petroleum Company, and Regional President BP Amoco plc. (covering the Middle East, the Caspian Sea region, Egypt, and India),” according to his company biography.

“Sad, But Not Surprising”

Investigative journalist Jeremy Scahill told Democracy Now! in a 2009 interview that TigerSwan did some covert operations work with Blackwater USA, dubbed the “world’s most powerful mercenary army” in his book by the same name. Blackwater has also guarded oil pipelines in central Asia, according to Scahill’s book.

Reese advised Blackwater and took a leave of absence from TigerSwan in 2008 in the aftermath of the Nisour Square Massacre, a shooting in Iraq conducted by Blackwater officers which saw 17 Iraqi civilians killed. TigerSwan has a business relationship with Babylon Eagles Security Company, a private security firm headquartered in Iraq which also has had business ties with Blackwater.

“It is sad, but not surprising, that this firm has ties to the US interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq,” Medea Benjamin, co-founder of the women-led peace group CODEPINK and the co-founder of the human rights group Global Exchange, told DeSmog. “It is another terrifying example of how our violent interventions abroad come home to haunt us in the form of repression and violation of our civil rights.”

The North Dakota Bureau of Criminal Investigation and the Private Investigation and Security Board are also conducting parallel investigations to the one recently completed by Morton County. TigerSwan did not comment on questions posed about their contract.

Featured image credit: Flickr / Chuck Holton

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 21, 2016 | Indigenous Autonomy, Reclamation & Expropriation

Featured image: The Wixárika community of San Sebastian Teponahuaxtlán or Wuaut+a is preparing to send 1,000 members to the remote Nayarit community of Huajimic to take back from the ranchers lands that the courts have ruled belong to the Wixárika. Photo from Facebook/San Sebastian Teponahuaxtlán.

by Tracy Barnett / Intercontinental Cry

A contingent of at least 1,000 indigenous Wixárika (Huichol) people in the Western Sierra Madre are gearing up to take back their lands after a legal decision in a decade-long land dispute with neighboring ranchers who have held the land for more than a century.

Ranchers who have been in possession of the 10,000 hectares in question for generations say the seizure is unlawful and that they will not hand over the land — setting the scene for a showdown that observers fear may end in violence.

Leaders of the Wixárika community of San Sebastian Teponahuaxtlán have announced their plans to accompany the authorities of the federal agricultural tribunal to carry out an enforcement action on the first parcel, a 184-hectare ranch in the state of Nayarit, on Sept. 22, and called on state and federal law enforcement officials to send police forces to prevent a conflict. Until the time of publication, neither the Nayarit nor the federal authorities had agreed to send police to maintain order, so both parties are hoping for the best but preparing for the worst.

The Nayarit community of Huajimic in the municipality of La Yesca has a long tradition of ranching. Ranchers of Huajimic have titles to their land that date to 1906, but the courts have ruled that the Wixarika land claims go back to the Spanish land grant of 1717. Photo from Facebook/Huajmic, Nayarit.

“We’re hoping they’ll accept the decision which is now law: that they lost the trial. They had the opportunity to legally prove that they really had the documentation and they didn’t have it,” said Miguel Vázquez Torres, president of the communal lands commission of San Sebastian. He is aware of the potential for violence, he said, “but the community is not going to sit with its hands crossed. We are prepared.”

Ranchers have titles to the land that go back to the early 1900s — but San Sebastian has the original grant from the Spanish crown that dates to 1717, and is backed by a 1953 presidential resolution. In all, 10,000 hectares is at stake, for a total of 47 different claims. The agrarian court has ruled in favor of San Sebastian in 13 of those cases; the remainder are still in process.

Rosa Carmen Dominguez Macarty, an attorney representing some of the ranchers of Huajimic, disputes the version presented by Wixarika attorneys, saying that only two of the sentences are definitive, and that all the rest are still under appeal. The ranchers are appealing the 1953 presidential resolution, saying it is based on a document that is invalid.

“It’s a social injustice,” she said. “These are very simple people; they are fathers, they are mothers who work the land themselves, and that’s how they support their families. It would be really sad if through the government’s disregard, something unpleasant were to happen.”

Vázquez said that two families who have no land have already been granted permission by the community assembly to establish homesteads on the parcel and that the assembly plans to send a rotating contingent of community residents to stand guard for several months — “as long as it’s necessary so that the families can feel safe and comfortable.” The long-term plan, he said, is to establish another settlement in the area, as San Sebastian’s existing towns are becoming overcrowded.

Dominguez argued that the local inhabitants have worked the land for generations and turned it into a highly productive area. Local residents suspect the Huicholes have another ulterior motive for taking back the land, which they have never worked: to exploit the mineral deposits that supposedly lie beneath.

Members of the Wixarika community of San Sebastian Teponahuaxtlán protesting for land reform in Guadalajara in 2014. Photo from the Facebook/San Sebastian(Wuaut+a).

Complicating matters is that San Sebastian lies in the state of Jalisco, while the contested land lies in Nayarit, where the ranchers have been outspoken in their opposition to the court decision and have been organizing in resistance to the return of the land to the Wixárika.

“Jalisco vs. Nayarit: Blood will run,” screamed one headline in a Nayarit newspaper. Meanwhile, Nayarit Gov. Roberto Sandoval reportedly has sent messages of support to ranchers.

“The governor promised us that while he is in office, we would not have to turn over a single meter of land to the Huichols,” one of the landowners told local reporter Agustín Del Castillo of Milenio newspaper.

Indeed, it’s no accident that the conflict crosses state lines, according to anthropologist Paul Liffman, author of the book Huichol Territory and the Mexican Nation.

“In fact that’s the deep history of Jalisco and Nayarit,” Liffman said in a recent interview. “Nayarit was part of Jalisco, and it separated in 1917, in part for the ranchers who wanted more political autonomy and also wanted to kick out the Indians.”

During the early years of the 20th century, the government encouraged settlers to make land claims on apparently abandoned land. It was during that period that major encroachment began to occur on Wixárika land, and the courts granted titles based on the erroneous assumption (or pretext, as Liffman says) that the land was unoccupied.

Tensions have flared periodically since the land was taken but the Wixárika had no legal recourse until the government created an agrarian court system in the 1990s, said Ruben Avila Tena, the attorney representing the community of San Sebastian. Soon afterwards that community began a legal process of reclaiming its land.

Jalisco law enforcement has agreed to be present, but only up to the state line; thus far the Wixárika leadership has received no such assurances from the Nayarit authorities, nor from the federal government.

“I’m not sure what the Jalisco police can do, besides cheering them on from the other side of the border,” commented Avila Tena. “It’s actually a very worrisome situation.”

Avila said sources in the Agrarian Tribunal have told them that the Nayarit police have no intention of supporting the Wixárika on Sept. 22. Agrarian Magistrate Aldo Saul Muñoz López spoke to this reporter by telephone but said he could not grant an interview by telephone, only in person in the Tribunal regional offices in Tepic, Nayarit.

“We did what corresponds to us as a federal tribunal, we notified all of the relevant authorities of Nayarit. If they don’t respond, it’s something that escapes my authority,” said Muñoz López, but would not give further information by phone.

Liffman likened the current conflict in San Sebastian with one that arose in the 1950s under the Huichol leader Pedro de Haro. Haro built a movement that ultimately procured the 1953 presidential resolution confirming that San Sebastian was the legal owner of the land. But as in the present case, the government didn’t provide any enforcement mechanism, and the local residents refused to give up the land. A band of armed Huichols took the matter into their own hands and marched to the Canyon of Camotlán, where they reportedly burned down a farm, drove out local residents and reclaimed the land.

Photo from the Facebook pages of the community of San Sebastian (Wuaut+a).

Santos de la Cruz Carrillo, a Wixárika leader and also an attorney on San Sebastian’s legal team, said the community has been urging the federal authorities to attend to this case for five years under a program that would offer financial compensation to the current landholders.

“It’s been five years since the community of San Sebastian asked the federal government to attend to this situation, to support the landholders with compensation”, said de la Cruz. “But the ranchers showed no interest in the compensation; they always said they want the land, so the community chose to take possession.”

Finally, in a meeting in March of this year, an official with that program told San Sebastian authorities that there was no money to pay restitution to the ranchers. That’s when they made the decision to move ahead with the process of retaking the lands, said Avila.

The Wixárika authorities have done everything in their power to seek compensation for the ranchers in the hope that a conflict could be avoided, said Avila. “This case was decided in their favor more than two years ago,” he stressed. “The community didn’t want it to be enforced like this, they were trying to get the federal government to indemnify the landholders. When they couldn’t do that anymore, they said, it can’t be helped, we will have to ask the tribunal to enforce the law.”

Liffman warned that the situation was not to be taken lightly; the area has changed radically since the times of Pedro de Haro, he said, with a significant amount of drug production now occurring throughout the territory.

“The region has become much more heavily armed,” he said. “San Sebastian has been the most violently disputed area in the sierra over the past several years…. it’s big-scale transnational narcos now, it’s not just some ranchers with pistols on their belts. So if it does come to that, it could be a bloodbath.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 15, 2016 | Obstruction & Occupation

by Red Warrior Camp

Mandan, ND… Water protectors stopped construction at two Dakota Access Pipeline sites on September 13, northwest of Mandan through nonviolent direct action.

At approximately 10:30 a.m. CST, two water protectors “locked down” to heavy equipment at the first action site. One of the individuals was locked onto the machine for nearly 7 hours.

Trained medics, media, legal observers and police liaisons were on hand to offer support and were also arrested.

Separately, water protectors successfully and peacefully stopped construction at the second site. A worker pepper sprayed one of the water protectors before leaving the scene.

Law enforcement began to arrive within the hour, followed by a large bus load of police dressed in full riot gear. An initial police line was formed with officers toting pellet guns. Filing in behind them was a second line of officers pointing large semi-automatic rifles at the water protectors.

The water protectors were immediately told that they were trespassing and subject to arrest. Morton County Sheriff’s office confirmed that there were 22 water protectors in custody by 4:00 p.m. The majority of those arrested are charged with Criminal Trespass, a Class B Misdemeanor.

The two individuals who locked down to the equipment are charged with Criminal Trespass, Disorderly Conduct, and Obstruction of a Government Function.

The Morton County Jail booking process of the water protectors continued on into the evening hours. Jail officials informed the Camp’s legal team that the ND States Attorney, Al Koppy, had ordered that only a North Dakota licensed attorney could visit the jailed water protectors, which is a violation of their constitutional right to counsel of their choosing for initial consultation.

The volunteer legal team assisting the water protectors called upon Chad Nodland, a local attorney who was also met with resistance by Morton County Jail staff. Although some of the inmates had been processed, the jailers informed Nodland that he would have to wait until all 22 arrested were processed before he could speak to them individually.

Morton County Sheriff’s Office refused to comment at press time. The water protectors’ bond hearing is scheduled for 1 p.m. CST on Wednesday, September 14th at Morton County Court House in Mandan, ND.

To support supplies for the Camp and the ever-increasing legal costs from the Red Warrior Camp please visit our website and click on DONATE.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 12, 2016 | Male Violence, Rape Culture

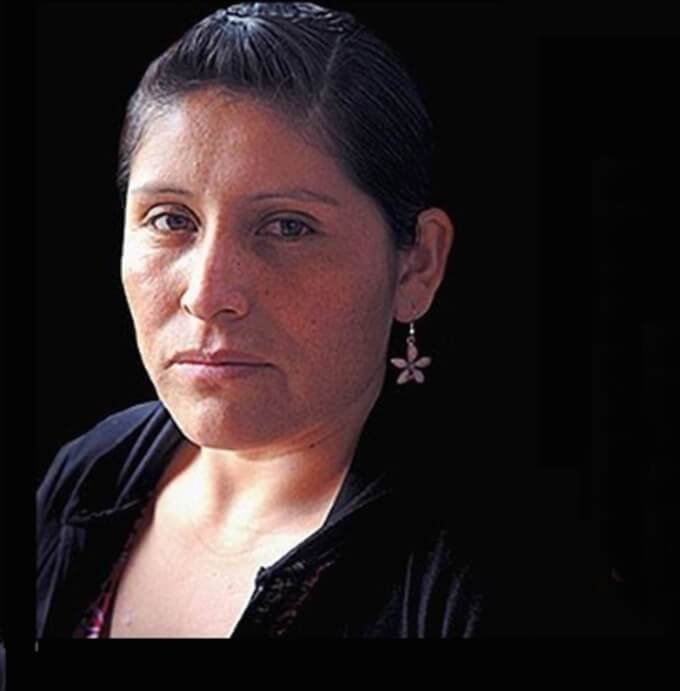

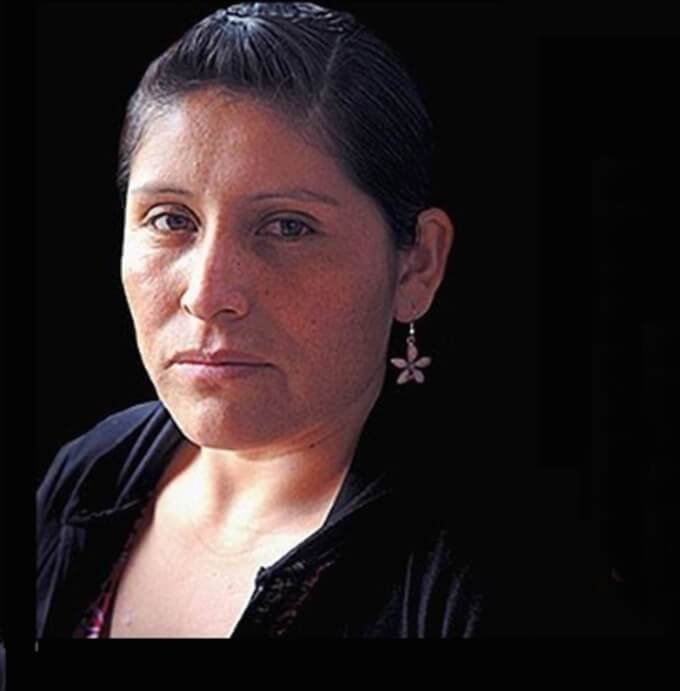

Quechua Bolivian woman unfairly sentenced to life in Argentina

Reina Maraz Bejarano was the last person in the courtroom to understand that she had just been sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly murdering her husband.

Maraz is from an indigenous community in Bolivia. Like many women in rural Bolivian communities, she was raised speaking the local language, not Spanish. On the day she was sentenced by the Argentine justice system, Maraz’s interpreter was translating the judges’ words from Spanish into Quechua so that she could understand. Married at 17 years old, a mother shortly after and subject to a violent marriage, Maraz was 22 when she was arrested for the murder of her husband Limber Santos. She was 26 in November 2014, when her future was determined by three Argentine judges. At that point she had already been imprisoned for four years. Because she couldn’t fully understand Spanish, she spent nearly a year of that jail time without understanding that she was accused of being responsible for her husband’s death.

Maraz’s case is emblematic of the ways in which both the dominant culture and the judicial system abuse women, especially indigenous women. For Maraz, this means being a survivor of physical and psychological violence. Then came the double injustice of being blamed for that violence by the Argentine state. Now she is a victim of a judicial system gone wrong.

A Long Path of Migration and Violence

To tell the story of how Maraz was condemned to life in Argentina’s prisons that day in court in 2014, we have to rewind to 2009, the year Maraz came to Argentina with her husband Limber Santos and their two young boys.

There are more undocumented Bolivian immigrants in Argentina than in any of Bolivia’s major cities. Many migrate from rural areas like Santos’ community in Chuquisaca, Bolivia, and often whole families move. In Maraz’s case she had no choice: her husband threatened to take away their children if she did not accompany him to Argentina.

Maraz testified in court that when they lived together in Bolivia her husband used to get drunk and beat her. Once they were in Argentina, the abuse continued. His family was complicit in the physical violence and took away Maraz’s documents.

After some months in Argentina, the Santos-Maraz family eventually settled in cramped rooms at a brick kiln where they worked in the city of Florencia Varela, in greater Buenos Aires. In a 2013 interview conducted in jail, Maraz’s interpreter translated her words, “Her children never went to school because her husband didn’t want them to. Reina was unhappy, there was never enough money because of Limber’s drinking.”

Santos was going on drinking sessions in the Buenos Aires barrio of Liniers with a man who worked and lived in the kiln also, Tito Vilca Ortiz. Vilca was to play an important role in what happened next.

Reina Maraz – in blue – with her defense lawyer and interpreter in court November 2014. Credit – Agencia ANDAR.

Sexual Violence and ‘that night’

Maraz told in court how one night Limber Santos and Vilca went out drinking. Around 5am, Vilca came back to the kiln and into Maraz’s room, where she was sleeping with the children. He woke her and horrifyingly told her ‘your husband owes me a debt, and he gave me you.’ Then he raped her in front of her children.

The lead judge, Marcela Alejandra Vissio, described the incident as improbable in her verdict because Maraz did not make a police report. But not filing a police report for rape is not unusual for women, who face significant barriers in the legal system such as reliving trauma and being victim-blamed. Data on unreported rape is hard to find in Argentina, as in many countries, but it is likely to be far under-reported. On top of the usual barriers, Maraz has the additional barrier of not fully understanding or speaking Spanish.

The aftermath of Maraz’s rape included a vicious beating at her husband’s hands. It also sparked violent conflict between Vilca and Santos.

On the morning of her husband’s death, 14 November 2010, Maraz got up at 4am to help him prepare for a trip to visit his sister to pay her back a debt. Maraz explained in court that Vilca was also up that morning, drunk. Limber Santos and he started arguing through the window of the room, and then Santos went out. At that moment, Maraz heard the sound of a padlock locking her and the children into the room.

The person who removed the lock and came into the room shortly after was not Maraz’s husband, but Vilca. She asked him where her husband was, and Vilca said Limber Santos had left for his sister’s. Then he raped her again, again in the presence of her two children.

The Aftermath of Limber Santos’ death

Maraz had no idea that her husband was dead at that moment. When there was no sign of him, she went to stay at her father-in-law’s house with her sons. She testified that she was afraid to stay at the brick kiln because of Vilca’s presence. And she went to the police and reported her husband as missing – she was worried he had been robbed when he didn’t appear at his sister’s.

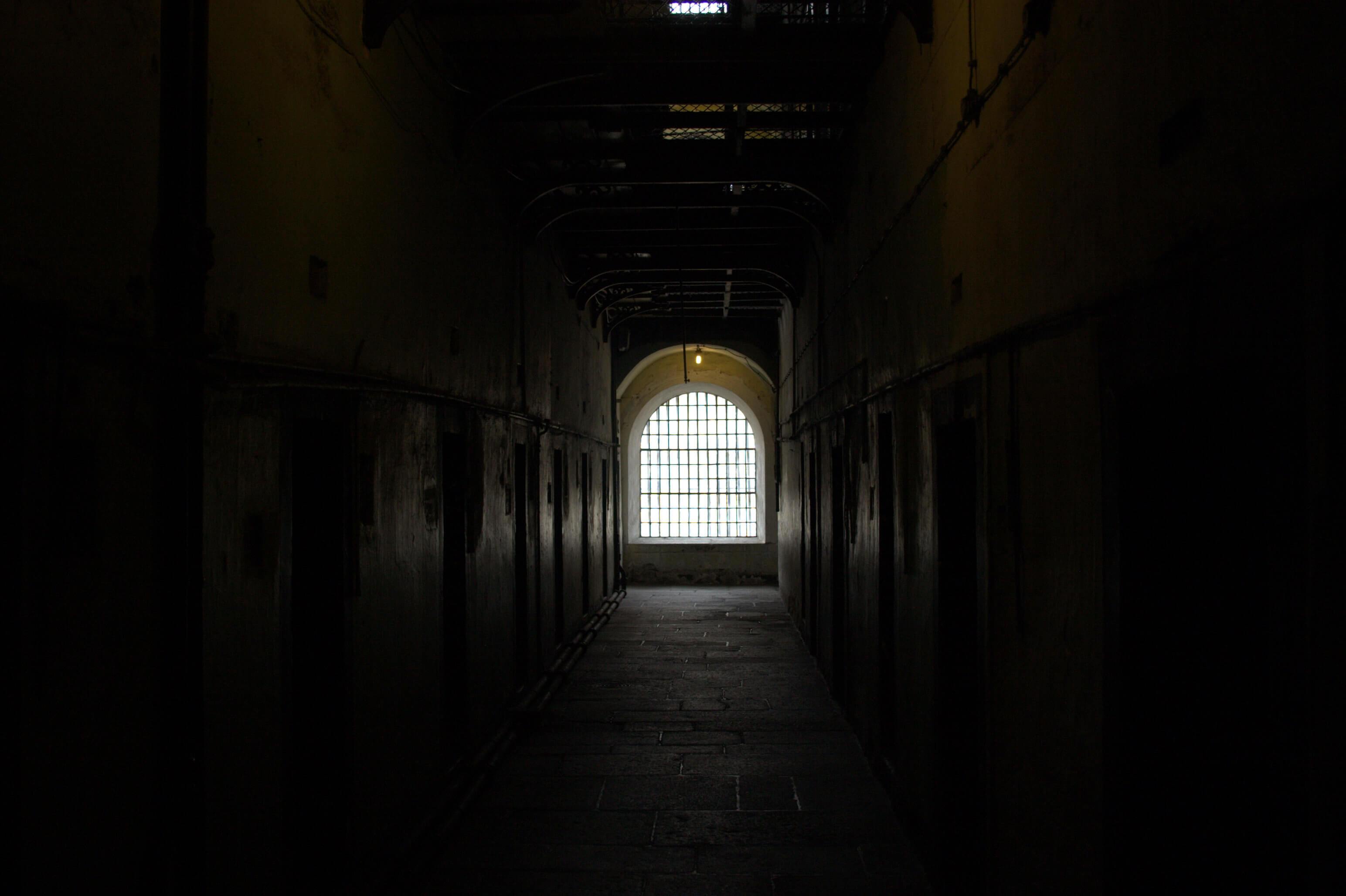

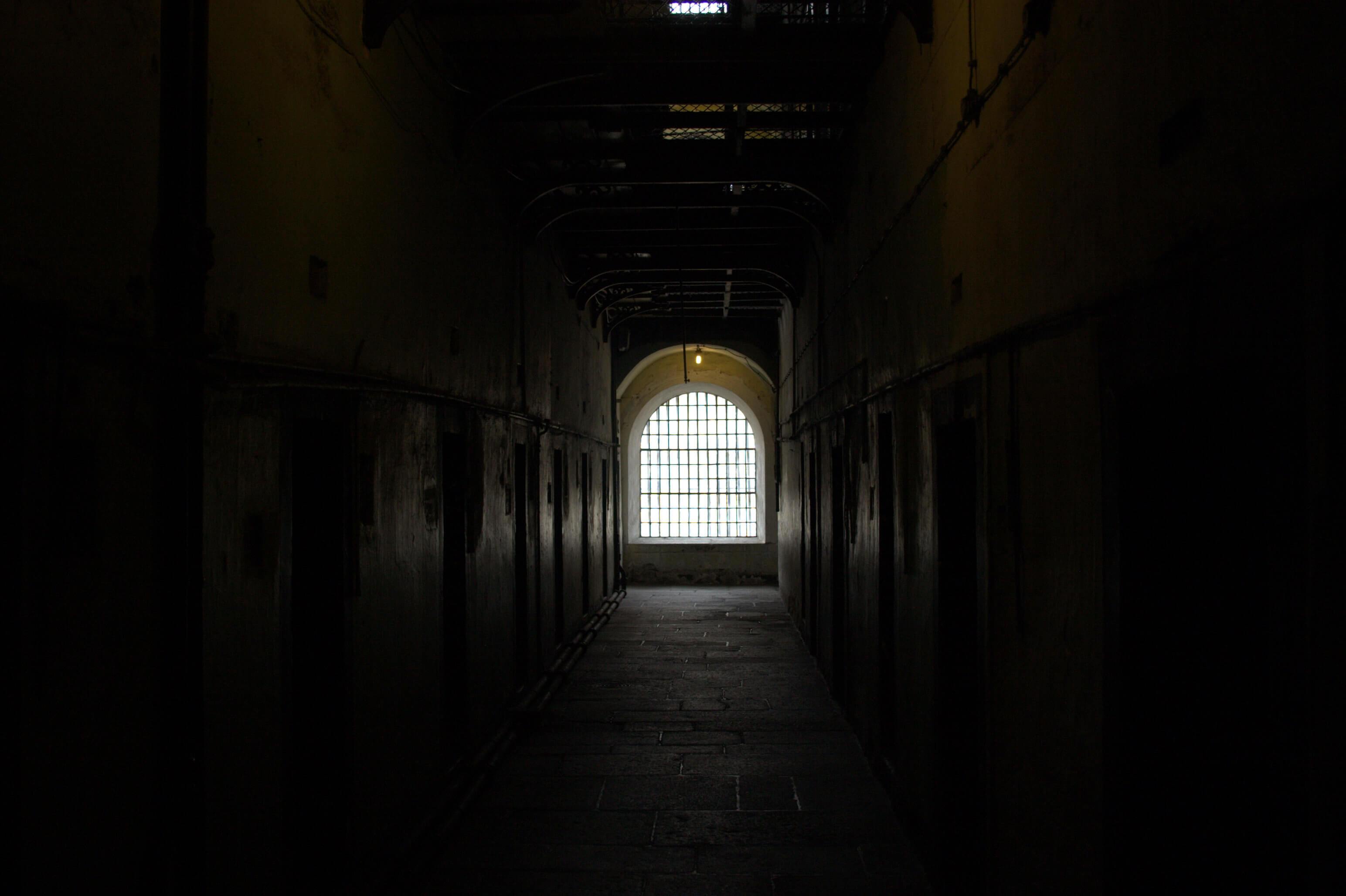

Limber Santos’ body was then found in a rubbish heap on the grounds of the brick kiln. Maraz and Tito Vilca were arrested and jailed as responsible. In jail, Maraz discovered she was pregnant. Her little girl was born in Unit 33 of Prison Los Hornos of Buenos Aires.

It took nearly a full year until Maraz was informed of the charges against her in her own language. The Argentine human rights advocacy organization La Comisión Provincial por la Memoria —‘The Provincial Commission for Memory’ — carried out one of its regular prison inspections in Prison Los Hornos and realized that Maraz was unable to communicate well in Spanish. They brought a Quechua speaker to visit her.

The Battle for an Interpreter

When Maraz faced trial in October 2014, she had Frida Rojas, a Quechua-speaking interpreter, at her side. Accessing this basic right for Maraz took over two years of advocacy and legal formalities, headed by the Commission for Memory.

The battle included a trip to the Supreme Court of Argentina, who ordered the criminal court to provide Maraz with an interpreter. Even so, the Argentine state made the Commission jump through many more hoops to get Maraz the interpreter she had a right to.

Dr. Mariana Katz is in charge of the Commission’s program for Indigenous and Migrant Peoples. Katz is a lawyer, and was an observer at Maraz’s trial. In a recent interview with Intercontinental Cry, Katz said, “In all of these delays and official proceedings, the person who suffers is Reina.”

She went on, “For the Commission, the legal basis [of Maraz’s conviction] is invalid, because from the very first moment [of her arrest] they should have provided her with an interpreter.”

Language Discrimination in Court

In another violation of rights, Maraz’s sister was forbidden by the judges from testifying in her native language, even though the Quechua interpreter was present in court that day.

“When they asked her questions it was clear she didn’t understand, because she was answering something different to the question she was asked,”Katz said. “On top of that, the judges were getting annoyed.”

To convict Maraz, the judges relied on testimony from her 5-year-old son who couldn’t speak Spanish fluidly. “When they brought the boy to declare, he had to be asked the questions several times, because he also has difficulties in Spanish,” explained Katz.

Maraz’s eldest son testified in a Gesell Dome, a one-way mirror system used by law enforcement. Three expert psychologists brought to testify by Maraz’s defense lawyer discredited the Gesell Dome testimony independently of each other. They said it was carried out as an interrogation using leading questions and not as it should be — a psychological test where the child is given time to express themselves through play. Despite all this, the judges did not take into account the three psychologists’ testimony.

The judges also ignored language subtleties that could have led to different interpretations of the boy’s testimony. It was also questionable whether to allow testimony from a 5-year-old who had been subject to traumatic experiences.

More Evidence Dismissed by Judges

Other important evidence was dismissed by the judges. Vilca was also arrested for Santos’ murder. While he was in jail, the Vice Consul of Bolivia to Argentina, Jorge Valentín Herbas Rodriguez, visited him. When Vilca began to tell him the story of what had happened the night of Limber Santos’ death, Herbas stopped him and told him to save it for court. Vilca died in jail before he got a chance to tell his story in court.

Herbas testified at Maraz’s trial. It was clear that Vilca was likely to have made a full confession had he lived. But the judges dismissed the word of the diplomat as “indirect testimony.”

On 11 November 2014, the three judges unanimously declared Maraz guilty of doubly aggravated homicide. The aggravating factors were premeditation and motive of robbery. The judges thought that Maraz and Vilca were lovers and planned to murder Limber Santos for the money he was carrying, which was barely $70US.

For this alleged crime, they condemned Maraz to a life spent in prison.

“They gave Reina the same sentence they give to perpetrators of the genocide [Argentina’s ‘Dirty War’],” Katz said.

Reina Maraz has been condemned to a life in prison. Her appeal is asking for her freedom. Credit -feelsgoodlost on flickr – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Reactions to the Sentence

The gross injustice of the Argentine judicial system did not go unnoticed. Feminist activists from several organizations protested outside the court (and have continued to protest). Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, Nobel prize winner and President of the Commission for Memory, wrote an article entitled The 3 Deadly Sins: Woman, Indigenous and Poor.

Maraz’s defense lodged an appeal in Argentina’s Court of Cassation (a certain type of appeal court that examines the interpretation of the law). The Commission together with feminist and human rights organizations have submitted a briefing to the judges (an Amicus Curiae). They stressed that Maraz did not have a fair trial. The vulnerabilities of a non-Spanish speaking migrant indigenous woman were not taken into account by Maraz’s judges, they said.

The demand is for Reina Maraz’s freedom. Failing that, advocates are calling for her sentence to be transmuted to the most lenient sentence for homicide in Argentina, eight years imprisonment, of which she would have already served six. There is no date set yet for the hearing of the appeal.

The Commission believes fully that Maraz is innocent. “We (the Commission) believe in Reina’s innocence, because for nearly 6 years, when she is asked about the facts, she always tells the same story with no cracks,” Katz said. “If it were invented, she would not be able to tell the same story without some level of error. This gives us the certainty that she is innocent.”

An emblematic case of indigenous discrimination

The lead judge Vissio repeatedly stated in her verdict that Maraz, Maraz’s sister Norma Bejarano, and Maraz’s eldest son were all fluent in Spanish. The court treated their need for interpretation of the Spanish language as no more than a defense tactic. The results of this attitude were rights violations; Maraz’s sister and son were never allowed to testify in Quechua.

By Argentine law, this was illegal, but the country’s courts still don’t have interpreters on file for more languages than English, French and Portuguese — notably, all colonial languages.

It’s a symptom of a deep-seated societal norm. “We have a problem in Argentina where people think that there are very few indigenous people, despite the history of indigenous struggle in the country,” Katz said. “There is a cultural conceptualization that indigenous people don’t exist.”

The judges’ actions and verdict speak to this attitude: migrants or indigenous peoples must speak the host country’s or the colonizer’s language; if they don’t, it’s their own fault. It is deeply unfair and deliberate: they are actions that make Indigenous Peoples invisible.

Reina Maraz, Survivor

Maraz was already a survivor of terrible violence; physical and psychological violence committed by her husband and his family, and sexual violence at the hands of Tito Vilca.

Now she is surviving violence at the hands of the Argentine state. Maraz is currently under house arrest, and suffering health problems. House arrest instead of jail was a small comfort achieved by activists, principally so that she can look after her young daughter. Her other two children are in Bolivia with her parents. She hasn’t seen them in a number of years; another type of punishment.

The hope now is that the judges who hear Maraz’s appeal are subject to enough pressure to drop the charges against her.

The Argentine state not only ignored Maraz’s proven status as a Quechua-speaking migrant and so prevented her from accessing a fair trial; they used her vulnerabilities as a weapon to condemn her. These are deeply misogynist and racist actions. Reina Maraz has already been unjustly imprisoned for six years. To free her now would be the bare minimum of justice.

All references come from the author’s original interview with Dr Mariana Katz; La Comisión Provincial por la Memoria’s full coverage of Reina Maraz’s situation and trial; and the verdict of Reina Maraz’s trial.