by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 7, 2014 | Climate Change, Indigenous Autonomy

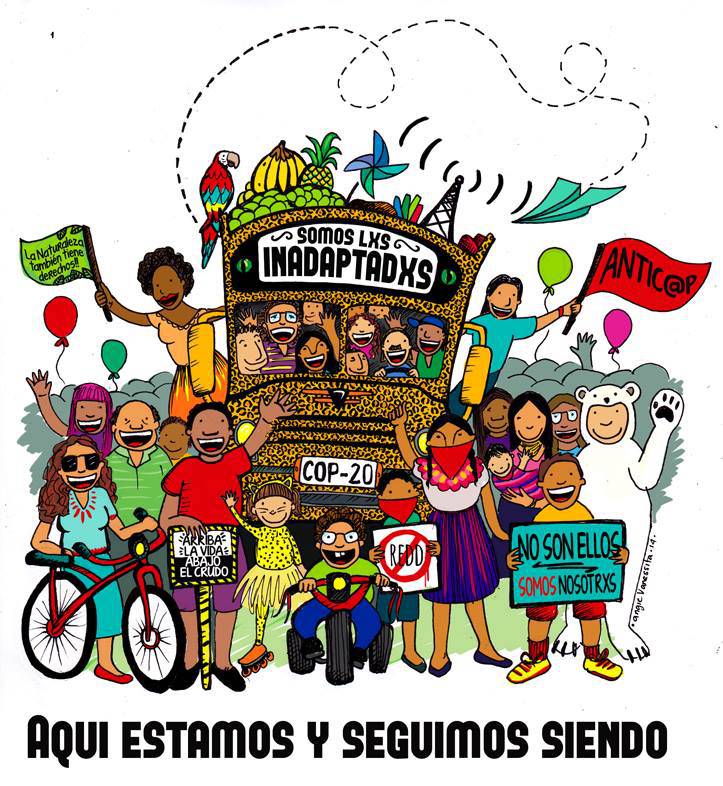

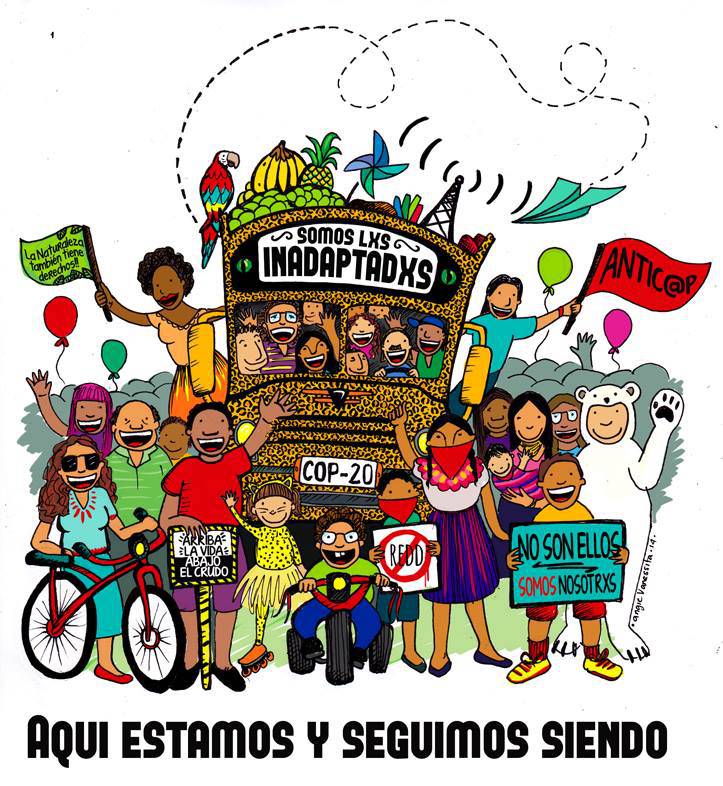

By Lxs inadaptadxs al cambio climático

22 years ago on this very continent was brought to the negotiating table the crisis of climate change. Many evasive proposals, claims to turn the crisis into an opportunity for business, denials, omissions and grand tragedies embody the climate crisis in the territories. A balance of 22 years of indifference and cynicism.

Governments and transnational interests continue to invest in the destruction of forests, rivers, oceans, jungles, mashlands, mountains and deserts; living spaces that end up being sacrificed in the name of “development” and “progress”.

In these 22 years, we are far from believing that the solution will come from governments; that the market will contribute to environmental conservation, or that the commodification of nature will protect the climate.

Our view is the way of indigenous communities that have known to preserved ecosystems, in farming communities who struggle to protect their lands, in women who work caringly in the rivers, in the children that keep alive their capacity of fascination with nature, and in the inhabitants of large cities who know that they have been robbed from nature since birth. Our guardians.

Us, the very ones who we are, have come here to convince you (and convince ourselves of the certainty that the world we want already exists), as there are colors of the earth, the suns that shine us, and the ways of our guardians that defend the territories around the globe.

This is why we call to find ourselves on the road to the COP20, to join our histories, our views, and our ways that demand climate justice under these guiding principles:

1. Maintain the fossil fuels underground is not only a priority to halting environmental devastation, but to end one of the evils that has so hurt and changed the pace of the climate in very few decades.

2. Ban the financialization of forests and the commodification of the functions of nature, as they are not a solutions to reduce emissions of carbon gases into the atmosphere; strategies which represent false solutions that have increased the destruction of ecosystems, the breakdown of communitarian social fabric and organization.

3. Water, as a common good can no longer be conceived as a commodity. Dams and hydroelectric dams are part of the mining and energy industries. The production of hydroelectric power is what keeps widening the gap of environmental devastation.

The aggressiveness with which the occupation of territories intends to expand itself does not depend on the political color of governments, but rather is linked to the perpetuation of the capitalist system under the same logic of accumulation at the expense of nature and communities.

Therefore, it becomes more urgent to find one another, Us.

They are the ones who will find the solutions- It’s us, the unadaptaded, the unadaptable climate change- It is us that can and must contain the war against nature.

From Lxs inadaptadxs al cambio climático

by DGR News Service | Oct 11, 2014 | Education

Our planet is being murdered. Mountains are falling. The oceans are dying. The climate itself is bleeding out and it may be beyond repair. Industrial civilization has entered its thrashing endgame. Technology can’t fix it and shopping—no matter how green—won’t stop it. And we are out of time.

The environmental movement has severely truncated its strategic thinking by insisting on education, consumer choices, and legislative initiatives as the only options for action. None of these can address the scale of the emergency facing our planet.

To save this planet, we need a serious resistance movement that can bring down the industrial economy. Authors Derrick Jensen and Lierre Keith with filmmaker Carson Wright are producing a film that will make the case for that movement. On the Side of the Living starts where the environmental movement leaves off: civilization can never be sustainable and is ultimately incompatible with life. People of courage and conscience are now stranded between moral agony and moral agency: the only certainty is that our one and only home will soon be a bare rock if we do nothing. Within that terrible urgency, the film confronts the possibility—and possible necessity—of principled, militant resistance.

$10,000 will see On the Side of the Living to completion. Go to https://www.indiegogo.com/project/preview/0c27882b to find out more and donate. If you love this planet, please give what you can. Your contributions will help us with film equipment, design, and production costs, as well as transportation expenses so we can deliver aesthetically striking footage with interviews from the movement’s most charismatic leaders.

Those in power are using their control over the culture industry to churn out story after story, book after book, film after film seducing us to forget and encouraging the masses to snuggle back into the warm illusion of civilization. On the Side of the Living combats the lies of those in power. Your support will help us spread our message to a greater audience.

A film supporting principled, militant resistant movement will probably not be overwhelmingly popular with the mainstream population. On the Side of the Living’s message will most likely prevent it from receiving material support from traditional sources of funding like corporations or government grants. But, as so many resistance movements have proven – from the efforts of the women suffragists, to the IRA, and to the Movement for the Emancipation of Niger Delta – a committed group of militant resisters can win.

Funding for On the Side of the Living will be provided by grassroots supporters like you. Support for a serious resistance movement is growing and your support for this film will speed the momentum.

What can you do

– Donate money to make it happen

– share with your networks

– share on social media

– share promotional posters and other media

– organise a fundraiser

Go to https://www.indiegogo.com/project/preview/0c27882b to find out more.

by DGR News Service | Sep 14, 2014 | Climate Change, NEWS

By Tom Bawden / The Independent

Carbon dioxide is being accumulated in the atmosphere at the fastest rate since records began, as scientists warn that the oceans and forests may have absorbed so much CO2 that their crucial function as “carbon sinks” is now severely threatened.

The jump in atmospheric CO2 is partly the result of rising carbon emissions as the world burns ever-more fossil fuels, according to the latest World Meteorological Organisation report, which finds the concentration of carbon increased by nearly three parts per million (ppm) to 396ppm last year.

But, crucially, preliminary data in the report indicates that the jump could also be attributed to “reduced CO2 uptake by the Earth’s biosphere” – the first time the effectiveness of the world’s great carbon sinks has been scientifically called into question.

Scientists said they were puzzled and extremely concerned by prospect of reduced absorption of the world’s oceans and plants, which they cannot explain and which threatens to accelerate the build-up of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere if the trend continues.

“That carbon dioxide concentrations continued to surge upwards last year is worrying news,” said Professor Dave Reay, of the University of Edinburgh.

“Of particular concern is the indication that carbon storage in the world’s forests and oceans may be faltering. So far these ‘carbon sinks’ have been locking away almost half of all the carbon dioxide we emit,” Professor Reay added.

“If they begin to fail in the face of further warming then our chances of avoiding dangerous climate change become very slim indeed.”

The plants and the oceans each typically absorb about a quarter of humanity’s CO2 emissions every year, with the other half going into the atmosphere, where it can remain for hundreds of years.

The last time there was a reduction in the biosphere’s ability to absorb carbon was in 1998, a year in which extensive forest fires and dry weather killed off lots of plants, dealing a blow to the world’s carbon sink.

But Dr Oksana Tarasova, chief of the atmospheric research division at the WMO, said this time it is much more worrying because there have been no obvious impacts on the biosphere this year.

“This problem is very serious. It could be that the biosphere is already at its limit, or it may be close to reaching it. Or it may be that it just becomes less effective at absorbing carbon. But it’s still very concerning,” said Dr Tarasova.

The worst-case scenario in which the carbon sink ceased to function at all would double the rate at which CO2 emissions accumulate in the atmosphere, significantly increasing the fallout of climate change, such as storms, droughts and temperature increases, Dr Tarasova said.

The latest WMO survey packed a second environmental punch – revealing that the oceans are currently acidifying at a rate that is unprecedented in the past 300 million years.

This is because they are absorbing about 4kg of carbon dioxide for every person on the planet, the report says.

The WMO’s findings intensified calls for co-ordinated global action to limit global warming to 2C, beyond which its consequences become increasingly devastating.

“We are running out of time. Past, present and future CO2 emissions will have a cumulative impact on both global warming and ocean acidification. The law of physics are non-negotiable,” said the WMO’s secretary-general Michel Jarraud. He added that, rather than rising, fossil fuel and other emissions badly need to come down.

Read more from The Independent: http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/carbon-dioxide-accumulates-as-seas-and-forests-struggle-to-absorb-it-9722224.html

Photo by Tienko Dima on Unsplash

by DGR News Service | Mar 30, 2014 | Male Supremacy, Strategy & Analysis, White Supremacy

By Kourtney Mitchell / Deep Green Resistance

On June 28, 1964, Malcolm X gave a speech at the Founding Rally of the Organization for Afro-American Unity (OAAU) at the Audubon Ballroom in New York. In the speech, he stated what became his most famous quote:

We declare our right on this earth to be a man, to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.

Interestingly, X was popularizing a line from a play titled Dirty Hands by the French intellectual Jean-Paul Sartre, which debuted in 1948:

I was not the one to invent lies: they were created in a society divided by class and each of us inherited lies when we were born. It is not by refusing to lie that we will abolish lies: it is by eradicating class by any means necessary.

There are some really important ideas presented in both of these quotes. Sartre succinctly summarized the primary struggle for the socially conscious – that society as we know it is divided into classes, and that social change is not achieved merely by refusing to behave like dominant classes, but by ultimately dismantling the power structures upholding this stratification.

X’s spin on this was equally profound. The white power structure of his time enacted brutal and morally reprehensible repression on the masses of black people in the United States, and X was stating the very real yet existential condition: that this repression was a dehumanizing tactic, upheld by violence and enslavement, and that the response to this repression must equal the scope of the problem. Simply put, white supremacism will use any and all means necessary to maintain power, and thus those fighting against it must do the same.

The modern environmental and social justice movement could learn a thing or two from these quotes. Any one who is not meditating in a cave should realize by now that this culture we live in – industrial civilization – is quickly killing the planet. All life support systems on Earth are declining, and have been doing so for several decades. As a matter of fact, since the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, generally considered the birth of the modern environmental movement, there has not been a single peer-reviewed article contradicting that statement.

This should ring some alarms for everyone, but surely for those in the movement, right? One would think so, but unfortunately this does not seem to be the case. Instead, what we are seeing is a continued ignorance of the true scale of environmental destruction, and a refusal to be honest about what it will take to stop it. What we are seeing is a constant faith on popular protest and nonviolence as the end goal of resistance, a hegemonic adherence to pacifism.

At the same time that nearly all native prairies are disappearing, and insect populations are collapsing, and the oceans are being vacuumed, and nearly two hundred species of animals are going extinct every single day, women are also being raped at a rate of one every two minutes. A black male is killed by police or other vigilantes at a rate of one every 28 hours. There are more slaves today than at any time during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. And indigenous cultures and languages are being wiped off the planet.

It is apparently certain that for all of our good intentions – our feelings of loving-kindness, taking the moral high ground and being the change we wish to see in the world – we are failing, and miserably. We are losing.

This must change.

It is time to face the truth, a truth climate scientists, indigenous warriors and anyone who is half awake have been telling us for a really long time – our planet is being killed, and we must fight back to end the destruction before all life on the planet perishes for good.

A starting point for establishing an effective response to environmental destruction and social oppression is to develop a clear understanding of the mechanisms for this arrangement. The dominant classes of people who are enacting this brutality utilize concrete systems of power to do so, namely industrial capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy and human supremacism.

These institutions of power are run by people – human beings, who instead of holding a reverence for life and love of freedom, value privilege and power above all else. This system is based upon, and would quickly collapse without, widespread and pervasive violence. Privilege is upheld by violence, because no one willingly cedes their freedom and autonomy unless forced to do so.

There is a necessary realization one must have when considering all of this, and it is a realization many in the so-called movement are yet to have: as the oppression of human and non-human communities and the destruction of the planet is being enacted by a particular class of people – that is, a group of people sharing a real or perceived identity and having similar goals and the means to achieve those goals – it is also being endured by a particular class of people.

Men, as a class of people whose collective behavior has a very real effect, are oppressing women as a class. This is not to claim that every single man on the planet has some palpable sense of hating women, but it does mean that to be a man in this society is to behave in a socialized manner that oppresses women.

Whites as a class of people are oppressing people of color. This is not to say that every single white-identified person on the planet has some palpable sense of hating people of color, but that to be white in this society is to behave in a manner that oppresses people of color in at least some ways.

If the violence is enacted by classes, the resistance must also exist on the class-level. It has never been enough for the individual to make personal, lifestyle changes so that they can feel better about themselves while the rest of the people in their class suffer. Systems of oppression are not defeated by individuals – they are defeated by organizing with others, a collective struggle.

This is what it means to be radical. As radicals, we aim to get to the root of the problem. Radical anti-racists understand that the white identity is based upon privilege, and that privilege is inherently oppressive to people of color. Radical anti-sexists understand that the concept of gender is built upon male dominance and female submission, which is inherently oppressive to women. And radical environmentalists understand that industrial civilization – based upon extraction, destructive agricultural practices and the genocide of indigenous cultures – is killing the planet.

From there, we draw the line. A radical’s primary goal is not to combat the symptoms of oppression – we do not merely wish to navigate the gender spectrum, toying with it at will as some kind of protest. We wish to abolish gender, recognizing it as the primary basis for women’s oppression. And we do not wish to merely give people of color a bigger slice of the pie in the white supremacist power structure. We wish to abolish white supremacy altogether, and furthermore to overcome the concept of race itself. Radical environmentalists cannot afford to continue to espouse technological fixes for a problem caused by technology and extraction. No, industrial civilization is wholly irredeemable, and no amount of technology can fix it.

What should be apparent is that our movement needs more than nonviolence and good feelings. We need to mount a serious threat to the power structures, one that is forceful and continuous. We need militant action. Those killing the planet will not stop unless forced to do so.

Nonviolence is a powerful tactic when correctly applied, but it alone cannot match the scale of destruction. When coupled with strategic attacks on the infrastructure of oppression, it can result in concrete, lasting change.

And this is the strategy of Deep Green Resistance. As an aboveground movement, we use nonviolent direct action, putting our bodies between life and those who wish to destroy it. Though we have no connection to (and no desire to have a connection with) any underground that may exist, we actively support the formation of an underground, encouraging militant resistance that will bring down oppressive institutions for good.

DGR is also dedicated to the work of helping to rebuild or to build new, sustainable human communities. We are working towards a culture of resistance – where oppression and ecocide are not tolerated, and where people incorporate resistance into their everyday lives. We work to establish solidarity and genuine alliance with oppressed communities, always keeping an eye towards justice, liberating our hearts and minds from the hegemonic tendencies of privileged classes. DGR understands that marginalized communities have been on the front lines of resistance from the very beginning, defending their way of life and reclaiming their autonomy. For too long, pacifists and dogmatic nonviolent activists have left the hard work of actual resistance to those marginalized groups, shying away from the real fight. No more – it is now time for men to combat sexism, for whites to combat racism, and for the civilized of this culture to fight against industrial empire and bring it down.

This analysis and this strategy should be inspiring. But what is more inspiring is that we have the means to achieve our goals. We know how to bring down industrial capitalism, which is controlled by critical nodes of technology and extraction. When these nodes are attacked and brought down in a way preventing their rebuilding, the system begins to collapse. The mechanisms of control – the military, the police and the media – cannot operate without consistent input of fossil fuels and willing agents.

When this system falls, the living world will rejoice. Two hundred species of animals who would have gone extinct will instead live and flourish. Indigenous communities will reclaim their traditional homelands. The salmon will begin to spawn anew with each dam taken down, and the rivers will rush with life.

This is the world for which we fight. And we intend to win.

Let’s Get Free! is a column by Kourtney Mitchell, a writer and activist from Georgia, primarily focusing on anti-oppression and building genuine alliance with oppressed communities. Contact him at kourtney.mitchell@gmail.com.

by DGR News Service | Mar 20, 2014 | Climate Change

By Renee Lewis / Al Jazeera

Climate change may be stunting fish growth, a new study has said. Fish sizes in the North Sea have shrunk dramatically, and scientists believe warmer ocean temperatures and less oxygenated water could be the causes.

The body sizes of several North Sea species have decreased by as much as 29 percent over a period of four decades, according to the report, published in the April issue of Global Change Biology.

The report presents evidence gathered as researchers followed six commercial fish species in the North Sea over 40 years. Their evidence showed that as water temperatures increased by 1 to 2 degrees Celsius, an accompanying reduction in fish size was observed.

It is generally accepted among scientists that decreased body size is a universal response to increasing temperatures, known as the “temperature size rule,” the report said. But before this report, led by scientists at Scotland’s University of Aberdeen, there was no empirical evidence showing this response in marine fish species.

The scientists warned that fish stunting cannot be unequivocally blamed on temperature changes, but they did observe fish stunting across varying species and backgrounds that coincided with a period of increasing ocean temperature.

Other factors that could have influenced fish size include fisheries-induced evolution and intensive commercial fishing — which favors larger specimens. But, the scientists said, these causes would not be likely to affect growth rates across species, which was observed in the North Sea study.

Scientists at the University of Washington have been working on a similar study, looking at many species of fish from Alaska to California. Tim Essington, an associate professor of aquatic and fishery sciences at UW who is working on the study, said he was looking into whether changes in fish body size could be related to environmental parameters.

“We haven’t seen the same strong response,” Essington told Al Jazeera. “But we have seen variation in the sizes of some stocks, like halibut. Its body size has been shrinking sharply over the past 10 years, and has resulted in reduced catch quotas and higher prices at the supermarket.”

He said various factors explain why UW results were different from those of the Scottish team. University of Aberdeen scientists were looking at a much more localized area and a unique data set, and had many more years of data to make comparisons.

Overall, Essington said the Aberdeen findings represented a plausible hypothesis that should be looked at more closely, and that warmer temperatures could explain the stunting.

“Fish aren’t any different than us. It’s all about the difference between how much we eat and how much energy we expend. And they’re arguing that temperature is changing the fishes’ energy versus expension rates,” which could result in smaller sizes, Essington said.

The Aberdeen findings echoed earlier model-derived predictions that fish would shrink in warmer waters. Those projections for future fish size reduction are already being seen in the North Sea, scientists said.

The first global projection of the potential for fish stunting in warmer, less oxygenated oceans was carried out by the University of British Columbia in 2012, and published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The projection said changes in ocean and climate systems by 2050 could result in fish that are 14 to 24 percent smaller globally.

“It’s a constant challenge for fish to get enough oxygen from water to grow, and the situation gets worse as fish get bigger,” said Daniel Pauly, principal investigator with the University of British Columbia’s Sea Around Us Project, and the co-author of the UBC study.

The study warned that strategies must be developed to curb greenhouse-gas emissions or risk disrupting food security, fisheries and the very way ocean ecosystems work.

From Al Jazeera America: http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/3/19/report-climate-changestuntingfish.html