by DGR News Service | Feb 12, 2016 | Culture of Resistance, Strategy & Analysis

Edited transcription of an interview by John Carico for The Fifth Column

How do you feel about Dr. Jill Stein and the Green Party of America?

I’m not a huge fan of the Green Party. I did a talk ten years ago at the Bioneers conference, which is about social change and environmentalism. One year their tagline was “the shift is hitting the fan,” about paradigm shifting. The thing that broke my heart was, so far as I know, I was the only person there who talked about power and psychopathology. I don’t think you can talk about social change without talking about power, and I don’t think you can talk about the destruction of the planet without talking about psychopathology. The Green Party has a lot of really good ideas, but how do you actually put them in place, given that those in power are sociopaths and the entire system rewards sociopathic behavior?

That doesn’t mean we need to give up or do nothing. A doctor friend of mine says the first step to a cure is proper diagnosis. If part of the disease that’s killing the planet is this sociopathological behavior, then fighting that sociopathological behavior needs to be part of our response.

I have voted Green in a couple of elections, and would vote again for a local Green. On the national level, the voting I’ve done was pretty much symbolic. I voted for Nader. I voted for a friend one time. The last time that I voted for any mainstream candidate was against Reagan in ‘84, and you pretty much had to vote against Reagan. But, interestingly, in 1980 I voted for Reagan and then realized I was an idiot, and voted Democrat in ’84. By ’88, I had an awakening and realized the whole system was just full of crap.

I do believe in voting on a local level. Voting on a national level may not change much, but locally, you can protect some things.

What warnings would you give young environmentalists as to how to differentiate green-washing from effective efforts?

The best way we learn is by making mistakes. The advice I give to young activists is to find what they love and defend it. Probably at some point, when they run up against the economic system, they’ll find themselves screwed over. That’s a lesson we all have to learn.

By the mid 1990s, I had already recognized that this culture is inherently destructive, but the “salvage rider” was still a big lesson for me. In ’95, activists all over the country had been able to shut down the Forest Service timber sales using the appeal process. Basically, if you could show the timber sales were breaking the law, you could appeal to have them stopped. Then they would have to produce a new document. Then you would stop them again by showing where they violated the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, etc. We were successful enough that Congress passed the salvage rider, wherein any timber sales that they wanted would be exempt from environmental regulations. The lesson was that any time you win using their rules to stop the injustice and stop the destruction, they will change the rules on you. There is really no substitute for learning this lesson yourself.

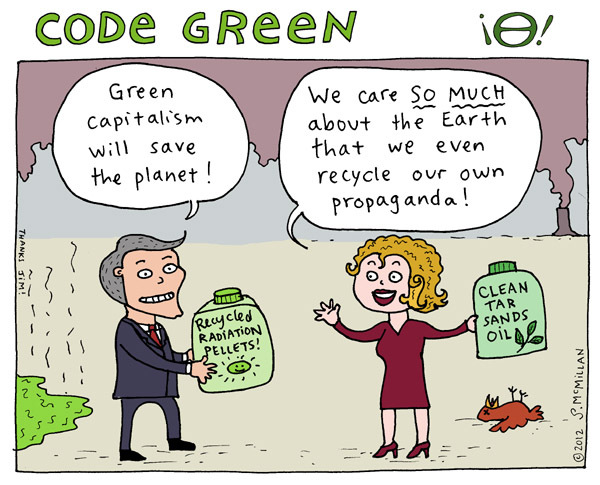

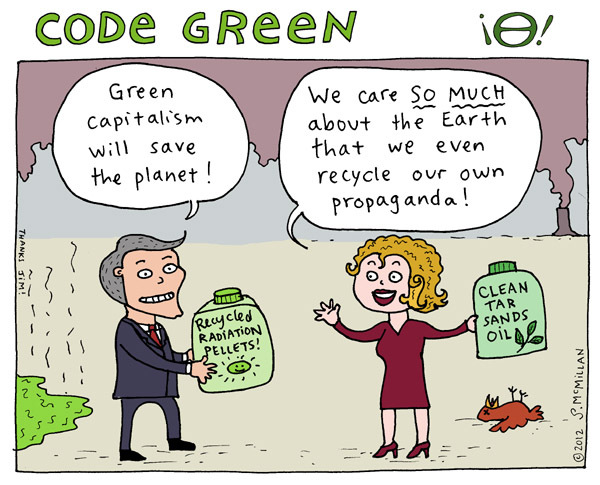

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

Recognizing Greenwashing comes down to what so many indigenous people have said to me: we have to decolonize our hearts and minds. We have to shift our loyalty away from the system and toward the landbase and the natural world. So the central question is: where is the primary loyalty of the people involved? Is it to the natural world, or to the system?

What do all the so-called solutions for global warming have in common? They take industrialization, the economic system, and colonialism as a given; and expect the natural world to conform to industrial capitalism. That’s literally insane, out of touch with physical reality. There has been this terrible coup where sustainability doesn’t mean sustaining the natural ecosystem, but instead means sustaining the economic system.

So when figuring out if something is greenwashing, ask, “Does this thing primarily help sustain the economic system or the natural world?”

That’s one of the problems I have with industrial solar and wind energy. They are primarily aimed at extending the party, not aimed at protecting salmon.

I would also ask young people to think about the linkages. A solar cell may be really groovy and you can power your pot grow but where did the solar cell come from? It required mining. It required global infrastructure. Even climate activists ignore these linkages. I heard one activist say, “Solar power has no costs, only benefits.” Tell that to the lake in Bhatu, China, who is now completely dead as a result of rare earth mining. Tell that to the people, human and nonhuman, who no longer can sustain themselves from the lake or from the land poisoned all around it.

A friend of mine says, “A lot of environmentalists start by wanting to protect one specific piece of land, and move on to questioning the entire culture of western civilization.” Once you start asking the questions, they don’t stop. “Why are they trying to destroy this piece of land?” leads to, “Why do they want to destroy other pieces of land?” Then you ask, “Why do we have an economic system based on destroying land? What is the history of this economic system? What happens when it runs out of frontiers? What happens when you have overshoot?” It’s important for young activists never to stop asking those questions.

Can you name successful revolutions of the past that you think we should look to when forming our own strategies? Where colonizing powers withdrew, and left the economy to its people?

Economy is a really hard word when you have a global economic system. We can talk about the Irish kicking the British out, or the Vietnamese kicking out the United States, but the real winner in Vietnam is Coca Cola, because Vietnam is still tied into the global economic system.

I think it’s great that the Indians and Irish kicked out the British and that the Vietnamese kicked out the U.S., so I’m not attacking revolution when I say this. But one of the problems is that when you defeat a certain mindset, it will often find expression in another way. When the United States illegalized chattel slavery, the underlying entitlement, where white people felt entitled to the lives and labor of the African Americans, was still there and found expression in a new way with the Jim Crow Laws. We see this all the way up to today with mass incarceration of African American males in such shameful ways. Like I said earlier, we need to keep looking at the linkages and, unfortunately, this makes one depressed. Because when you see a victory, oftentimes, you also see a backlash and a reconfiguration and reestablishment of the underlying bigotry.

We see this too with monotheism’s movement toward science, especially mechanistic science, where the world is not alive. The monotheism of the Christian sky-god did the initial heavy lifting by taking meaning out of the world and leaving it up there. Mechanistic science is really just an extension. We can say, “Wow, we really got rid of the superstition and the bigotry that has to do with Christianity,” but this belief in science is even scarier. At least with the Christian sky-god there was someone above humans. Now humans are making themselves into this new god and think they control the whole planet.

Having said that as a preamble, the film The Wind That Shakes the Barley highlights one of the smart things the Irish did. The film starts off with all these Irish guys playing hurling. When I saw this at first, I thought, “What the hell does this have to do with the Irish liberation struggle?” As I mentioned, one of the things we have to do is to decolonize ourselves. They did this in part by playing Irish sports, using Gaelic Language, and reading Gaelic Literature. A successful revolution begins with breaking identification with the dominat system. First comes the emotional part. After that, it’s all strategy and tactics; you look around and ask, “What do we want to do, blow something up, vote, peaceful strikes?”

This ties back into everything we’ve talked about so far. Are we identifying with a system or are we identifying with those we are trying to protect? We can say the civil rights movement was successful in the sense that African Americans now have a provisional right to vote. Of course mass incarceration targets black males and thus takes away their right to vote, but the movement was still successful in that it accomplished some aims. This was done by identifying as black voters. So, identifying is very important.

Several years out from the writing of Decisive Ecological Warfare, is there anything you would change in terms of strategy that you’ve learned since?

We don’t know because no one is doing it. All I know is that there are more than 450 dead zones in the world and only one of those has recovered — in the Black Sea. The Soviet Union collapsed, making agriculture no longer economically feasible there. They stopped agriculture and the dead zone has recovered enough that they now have a commercial fishery. That makes clear to me that the planet will bounce back when this culture stops killing it, presuming there’s anything left.

The image that keeps coming to mind is this body, which is the earth, and it keeps bleeding out because it’s been stabbed 300 times. All these people are trying to heal this body, and they are doing CPR and putting on bandages and everything else. But they’re not stopping the killer who’s still stabbing the person to death. We have to stop that primary damage. We have to recognize that we can’t have it all. We can’t have a way of life that relies on industrial capitalism and continue to have a planet.

Now, I haven’t really answered your question, mostly because of what I said at first: nobody’s doing it, so we don’t know what mistakes there are in the strategy. I’ve been saying for fifteen years that if space aliens came down to earth and were doing what industrial civilization is doing to the planet, we would put in place Decisive Ecological Warfare. We would destroy their infrastructure. This is an important point. We can make a very strong argument that World War II was won by the Allies, primarily in the killing fields of Russia. But I would argue that either first or second most important was the destruction of German industrial capacity. Similarly, the North won the Civil War not just because they had better generals, but because they destroyed the South’s capacity to wage war.

I don’t care how we do it; we can do it by voting, if that works. But we have to find a way to stop this culture from waging war on the planet.

Will Potter’s Green Is the New Red talks about the crackdown against Green movements. Do you have any advice for people who want to speak openly about resistance but are afraid of the repercussions? Where is the line between security culture and the need for movement building? The Invisible Committee says we need to tie the actions that have been done into a narrative. Is the problem that the media never covers the actions of those who, for instance, did direct action against fracking in New Jersey, and that any direct action the media does cover seems to follow the horrible lone wolf narratives? Do you think this stifles our movement?

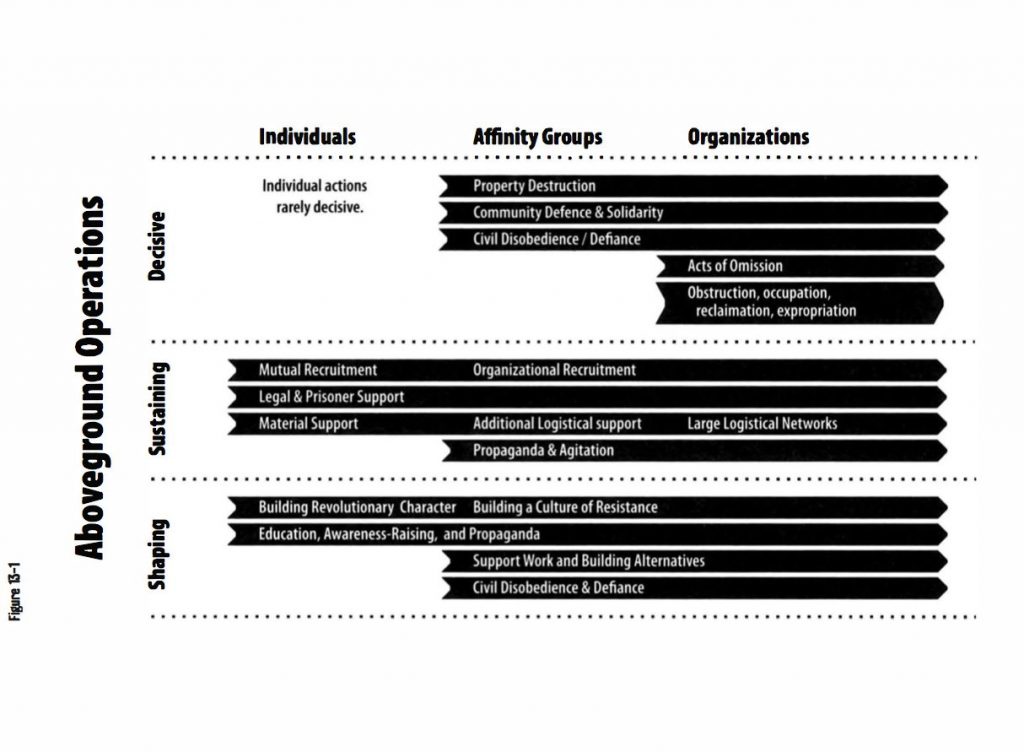

What you say makes a lot of sense. Coverage of direct actions, and the true reasons behind those actions, can’t be left to mainstream media. The movement needs people aboveground who can publish the narrative, and another separate group which is underground, to actually do it. Both roles are critical, but we need a firewall. Many activists have been arrested partly because they tried to do both. We in Deep Green Resistance are trying to fill that aboveground role, as is the North American Animal Liberation Front Press Office.

As for security culture…I think, sometimes, about the whole marijuana legalization movement (I realize this isn’t so much a successful revolutionary movement as a successful social movement). They’ve done a good job pushing an agenda that would have been unthinkable thirty years ago. They’ve done this by using this model, by being below ground with the growers and above ground with NORML. We can say the same thing about the IRA.

You need that firewall when you live in a security state, but we shouldn’t feel unnecessarily paranoid. Although surveillance is everywhere and they pretend they are God, those sitting at the top are not actually omniscient. Living in northern California, where the pot economy basically runs the entire economy, has helped me to a healthy understanding that the Panopticon is not as all seeing as it wants to be. (Again, I know there is a difference between A) growing marijuana, which many cops probably smoke or view with sympathy, and B) ending capitalism, which would freak out all the cops.)

I’m very naive about many things, including drug culture. But I used to teach at Pelican Bay, a Supermax Prison, and students told me that if you dropped them into any city in the world, they could find drugs within 15 minutes. I couldn’t even find a bathroom in 15 minutes! That means the underground economy is surviving the Panopticon very well; it isn’t omniscient.

The Green Scare did not succeed because of the power of the Panopticon, or because of brilliant police work. The cases of sabotage were solved by good old-fashioned stoolie, because Jake Ferguson was an abuser, junkie and a snitch. Basic security culture probably would have defeated the investigations.

Can you give a critique of anarchists and why you see a lot of their work as ineffective?

I had a conversation a couple years ago with a very famous, dedicated anarchist who has some critiques of anarchism, but didn’t want me to use his name because he knows if he says anything critical about anarchism he will get death threats. One of the big problems is that anarchism is open membership, in that anyone can become an anarchist simply by identifying as an anarchist. He says many who call themselves anarchist, aren’t; they are just antisocial and have found an ideological excuse for their bad behavior. He says anarchists have a long tradition of fighting for the eight-hour work day, or fighting againt fascism as in Spain. He says there needs to be a way to kick out people who are simply sociopaths who call themselves anarchists. I mean, here’s a quote by an anarchist/queer theorist: “Smashing the institutions of patriarchal racist capitalism goes hand in hand with being a repulsive perverted freak.” Seriously? We’re supposed to put this person in the same category as Goldman or Kropotkin? Are we going to let that person in, even if they are just a prick? Any group will have nutjobs: Republicans, Democrats, stamp collectors. But anarchism is so small, so vocal, and so open that the nut jobs really stand out and can discredit the larger group.

I’m also concerned about effectiveness. The individualist anarchists (as opposed to collectivist anarchists) have an active hostility toward organization. DGR isn’t alone in getting attacked for this, for being perceived as hierarchical. I’ve seen writing on this going back 40 years, with anybody who believes you can have an organization with a stable schema immediately being attacked as Stalinist. They attack the organization simply because it’s an organization. There is a great line by Samuel Huntington that says “The west won the world, not by the strength of its ideals, but by its application of organized violence.” (He’s actually a supporter of the western empire; he says it’s a good thing.)

I talk about this in Endgame. I have become convinced that the single most important invention of the dominant culture, which has allowed it to destroy the planet, is the top-down bureaucratic military style organization. I’m not saying we need to model our organizations after this, but it is really effective. It is how this culture was able to murder the Native Americans. They had one big army. In my experience, people can generally be very contentious. It’s really hard to get together on the same page.

I had a friend who was trying to start an environmental organization years ago. An indigenous member warned that 95% of the time would be spent dealing with personality conflicts, and the other 5% actually doing the work. It’s an accomplishment, albeit a terrible one, that the U.S. Military gets 5 million people to act toward one aim: killing brown people, or whatever it is they are doing. They have propaganda on TV and in print, they have the capitalist system which rewards bad behavior, they have an organizational schema and, on the other side, we are supposed to defeat them without being organized?

Civil War General McClellan lost against Lee due to piecemeal efforts. McClellan attacked in one place and Lee moved his troops back. McClellan attacked another place, and Lee moved his troops back. The Turkish military had a strategy of attacking in piecemeal, and lost every battle for nearly two hundred years. The Russians would attack en masse and the Turkish army would send in one unit at a time and get slaughtered. Nathan Bedford Forrest, a terrible racist but brilliant Civil War strategist, said, “The way you win a battle is getting there first with the most.” In any conflict you want local superiority.

You asked why I see anarchist strategy as oftentimes ineffective: if you’re fighting an organized force, you should try to be organized as well.

Can you give a definition of Radical Feminism, and a response to some of your detractors who’ve accused DGR of transphobia?

The question I would ask is “Given that we live in a rape culture, do you believe women have the right to bathe, sleep, organize, and gather, free from the presence of males?” If you do believe that women have that right, you will be accused of transphobia; you will receive death threats. If you are a woman, you will receive rape threats. I’ve been de-platformed over this, some trans activists have threatened to kill the children of DGR activists over this. All because I believe that women have the right to gather free from the presence of males.

I want to make clear that no one in DGR is telling anyone how to live. I don’t give a shit! I’m not saying people who identify as trans should get paid less for their work, or that they shouldn’t have whatever sexual partner they want. I’m not suggesting they should be kicked out of their house, or should be de-platformed from a university, or that anything bad should happen to them.

Somebody wrote me and said, “I have a a little five-year-old boy who loves to wear frilly clothes, loves to dance ‘like a girl’, and sing ‘like a girl’; doesn’t this make him transgender?” I wrote back and asked, “Are you saying only little girls can wear frilly clothes? Why can’t we just say ‘this is a little boy who likes to play with dolls, and sing in a high voice?’ Why can’t we just love and accept this child for who he is? What does it even mean to dance ‘like a girl’? ”

Shoddy thinking makes me angry. I know the trans allies are going to get mad when I say, “Women should be able to gather alone” because they will then ask, “Who are women? Aren’t trans who identify as women, in fact women?” My definition of woman is human female, and my definition of female is based on biology. Some species are dimorphic. Just like there are male marijuana plants and female marijuana plants, and male hippopotami and female hippopotami, there are male humans and female humans.

I want to say two things before anyone offers a counter-definition of ‘woman’:

1. A definition cannot be tautological. You cannot use a word to define itself. You cannot say, “A woman is someone who identifies as a woman,” any more than you can say, “A square is something that sort of resembles a square.”

2. A definition must have a clearly defined metric. If I said, “Here is a three sided thing, it’s a square,” you would say, “No, it’s not a square because a square has 4 sides.” You have to be able to verify. I can say I’m a vegetarian but I had great ribs for dinner. This destroys not only the word ‘vegetarian’ but also the word ‘definition.’ I would ask those who disagree with my definition, “What is your better definition that is verifiable, for the word ‘woman’?” and second, “Is the fact that I have a different definition for the word ‘woman’, which is defensible linguistically, so important that you think it’s acceptable for men to threaten to rape women?”

I’ve never publically discussed this point before, but I think this is an important issue to discuss. It’s part of a larger post-modern social movement that values what we think and what we feel over what is real. This takes us right back to the greenwashing, with people saying, “We have to come up with the economy we want.” No, first we have to figure out what the Earth will allow!

This culture has a deep hate for the embodied and for what is natural. Here’s a great example: I have coronary artery disease, and I told my doctor I was feeling better since I had been diagnosed. This was right before Obamacare kicked in, so I didn’t have insurance yet. The pain got less in that time, and I asked why. The doctor said that when the arteries get clogged, the body sends out capillaries all around it to basically do its own version of bypass surgery. I had never heard that before. We all think it’s some miraculous thing when someone cuts open your chest and does bypass surgery, but we don’t even think about it when the body does it itself. There is tremendous wisdom of knowledge in the body, and we have to learn to respect it. This is important, both on a larger global scale and on the personal scale. I think it’s really important to recognize how this culture devalues the body. How I feel is way less important than what is.

Can you talk a bit about left sectarianism?

This goes back to the machine-like organizational structure of the dominant culture, which I am not valorizing, but do recognize as really fucking effective. It’s been able to get people past sectarianism.

Over the years, I’ve gotten thousands of pieces of hate mail, of which only a couple hundred were from right wingers. I’ve gotten hate mail from anti-car activists because I drive a car, vegans because I eat meat, and anarchists because I believe in laws against rape. I’ve never understood why animal rights activists and hunters don’t work together to protect the habitat. I wouldn’t have a problem with that. I do believe in temporary alliances. Once that’s done, animal rights activists can sabotage the hunts.

There’s a great example from 300 or 400 CE. These two sects of Christianity fought, same name but one had an umlaut, and one didn’t. They killed each other — hundreds of people! — over the question “Do you believe the fires of hell are literal or figurative?”

I was talking to a guy about the left always attacking each other. He mentioned that where he lived in West Virginia, there used to be a single KKK chapter consisting of three brothers. Now they have three chapters, because they can’t stand each other. So it’s not just a problem on the left.

Instead of getting mad at sectarianism, which I’ve been doing for the past fifteen years, we need to figure out what to do about it. It’s probably part of the human condition.

My friend Jeanette Armstrong, an indigenous activist and writer, told me once, “We, in our community, have just as many squabbles as white people do. The difference is I know my great-grandchild might marry your great-grandchild, so we figure out how to get along.” I really like that. I think we just have to ask “What are we really trying to do?”

What’s wrong with me having a really strong disagreement with a trans activist, for example, and them having a really strong disagreement with me? We can both continue doing our work and, at worst, ignore each other. There are plenty of people with whom I disagree. Families have different political views all the time and still love each other.

The question I’ve been asked over the years that cracks me up is what it’s like at my house on Thanksgiving. One of my sisters is a petroleum engineer, and she used to be married to a guy who did cyanide heat leaching and owned a gold mine. Now she’s married to a guy who used to work for the NSA and now works for the Israeli Military. What do we talk about? We talk about football. My brother is a huge Seattle Seahawks fan, so go, Hawks! I don’t talk about environmental stuff; it’d just start an argument. So I don’t understand why we activists can’t agree to disagree.

Noam Chomsky, who really disagrees with the anti-industrial perspective, is another great example. I was scheduled to give a talk in Scotland, and they wanted to ask me about Chomsky blasting anti-industrialism. I really disagree with him on this, but I really respect his work, so my agent, a really smart person and also Chomsky’s agent, said just to say “I’m not attacking Chomsky. We just have a disagreement on this.” I don’t understand why we can’t do this more often. There is a limit, of course. Roman Polanski is a rapist, so it makes sense to talk about his personal life.

I can’t stand Richard Dawkins, have critiqued his work a lot, and have heard, individually, that he’s pompous. But I’ve never heard that he’s a rapist or anything so I don’t know why I wouldn’t just keep my critiques focused on his work.

I think film is really detrimental to communication, because it’s so removed from real life and the way we communicate. In order to move a film story forward, you need dramatic tension. So a lot of times you have people fighting who wouldn’t fight in real life, and because we learn to communicate from the stories we take in, we learn to be even more contentious than we otherwise would be.

I know someone who was on Bill Maher and was relatively polite. They got mad and said, “If you are ever on the show again, you have to interrupt people and be contentious, because that’s what makes the show work. We want Jerry Springer, we want people to throw chairs.” We may not really want that, but that’s what works for the spectacle. And then we learn that’s acceptable behavior.

I’m writing a book right now with a coauthor. We had a significant conflict Saturday, but both parties handled it in a mature fashion. We still have a significant disagreement, but we strengthened our friendship because we handled it maturely.

What are your thoughts on Prison Abolition?

When talking about prison abolition, I get a little nervous because I can’t wrap my head around it. Obviously the prison system is horrendous. But I’m not a prison abolitionist, because when I taught at the Supermax, the students agreed that the only way for prison abolition to work is if you’re going to kill a bunch of people. I knew a kid who was put out for prostitution at age four, and really, what chance did this kid have? He was really fucked up by the time he was six. Another kid was living on the streets of Oklahoma at six with his little brother. This guy is now doing life for murder. Probably the first time he knew where his next meal was coming from was when he got to prison.

My creative writing students used to pass around jellybeans, but warned me never to take anything from one inmate. He had tortured a person to death, and since getting to prison, he’d poisoned three people. Something, obviously, had happened to this guy.

A friend had a student who said to her, “I am so broken, I need to be kept out of society.”

Another guy — not sure if he was executed or died on death row — killed his wife and kid and put each heart in a separate pocket because “the blood couldn’t mix.” When he was on trial, he pulled out one of his eyes because “that’s how the feds were putting stuff into his brain.” That didn’t work, so he pulled out his other eye and ate it. I’m not saying he needed to be in prison as it currently exists, but he definitely needed to be separated from society. Or removed. What do you do with Ted Bundy?

I’m not saying that Ted Bundy makes the case for locking up some fifteen year old, and I’m not saying we shouldn’t eliminate for-profit prisons and the prison industrial complex. And I’m mostly against the death penalty — though I think Tony Hayward of BP should be executed, it’s outrageous as it is because it’s racist and classist. But the whole culture is completely messed up, and we can’t simply abolish all prisons without addressing the rest of the problems.

I had a student who said if he could change one thing about society’s perception of drug dealers, he’d destroy the stereotype of the drug dealer in an Armani suit. He said, “You try living in Oakland with three children and working at McDonalds; you can’t do it. Drug dealing puts food on the table.” Now he’s in prison which doesn’t help anybody.

Before I went to work in the prison system, I was completely apolitical on the drug war, because I never thought about it. But I became highly politicized because a lot of my students would have been perfectly fine neighbors as long as you either A) kept them off drugs, or B) made the drug legal like cigarettes. Many of my stdents did terrible things to get money for drugs, but if it had just been like cigarettes, they never would have murdered people.

One student was in because he was a marijuana dealer in the 1970s, and shot dead someone who tried to rob him. If he had been a shoe salesman and shot someone who tried to rob him, he wouldn’t have gone to jail for even one night, much less for the rest of his life.

A friend who was a police abolitionist went into communities known for police brutality, and got push back because the police are only one threat. The communities also have armed drug gangs, sometimes just as organized and just as nasty as the cops. The local people had no interest in police abolition until there was a community defense that made it practical. Similarly, Craig O’Hara said that anarchism is not about the eradication of all laws, but about making society such that you don’t need them. That’s it, exactly. You can’t push theoretical ideals at the expense of what people need for safety right now. I’ve seen anarchists get mad at women for calling the cops for rape!

I talked to Christian Parenti years ago about police. He observed that police have two functions: to stop meth addicts from bashing in the head of Grandma, and to bash in the heads of strikers. Two roles: to protect and serve, and to protect and serve the capitalists. Police like to emphasize the prior, whereas anti-police activists like to emphasize the latter. Parenti said they spend most of their time making sure people don’t drive 80 mph through a school zone. I don’t have a problem with someone getting a ticket for driving 80 mph through a school zone. But their most important social role is to bash in the heads of strikers.

We need to realize that our broad cultural conditions are really really, really terrible, and that something needs to be done about Ted Bundy until we have a society where Ted Bundys aren’t made.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 14, 2016 | Repression at Home

By Mark Hand / CounterPunch

Federal Bureau of Investigation and Department of Homeland Security agents have contacted more than a dozen members of Deep Green Resistance (DGR), a radical environmental group, including one of its leaders, Lierre Keith, who said she has been the subject of two visits from the FBI at her home.

The FBI’s most recent contact with a DGR member occurred Jan. 8 when two FBI agents visited Rachael “Renzy” Neffshade at her home in Pittsburgh, PA. The FBI agents began the visit by asking her questions about a letter she had sent several months earlier to Marius Mason, an environmental activist who was sentenced in 2009 to almost 22 years in prison for arson and property damage.

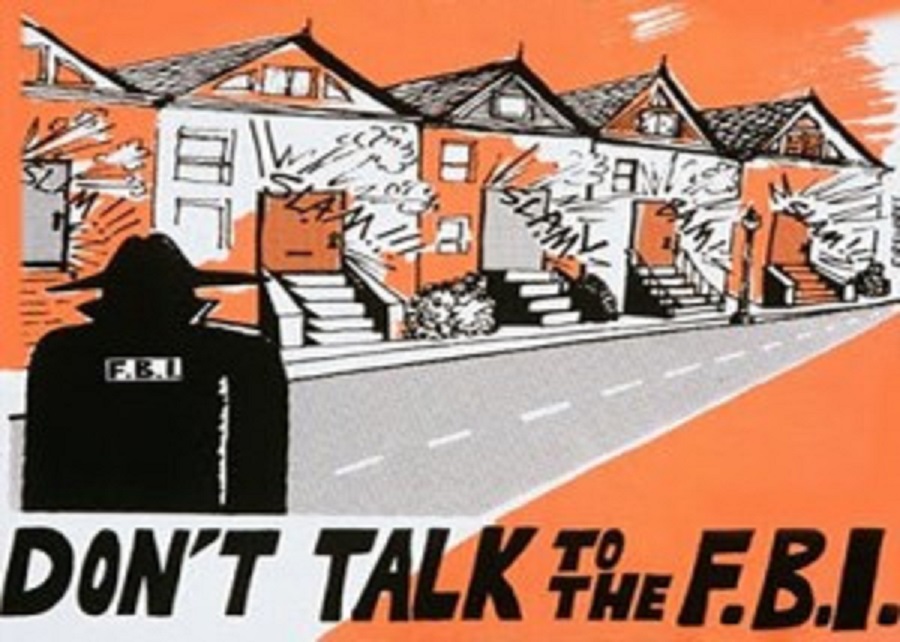

Neffshade told CounterPunch she refused to answer any questions from the FBI agents. Based on the line of inquiry, Neffshade concluded the FBI agents were not necessarily looking into gathering further information about Mason. “It seemed like they were pursuing an investigation into me, but who knows? I didn’t answer any of their questions,” she said. “It’s important to remain silent to law enforcement as an activist. It is a vital part of security culture.”

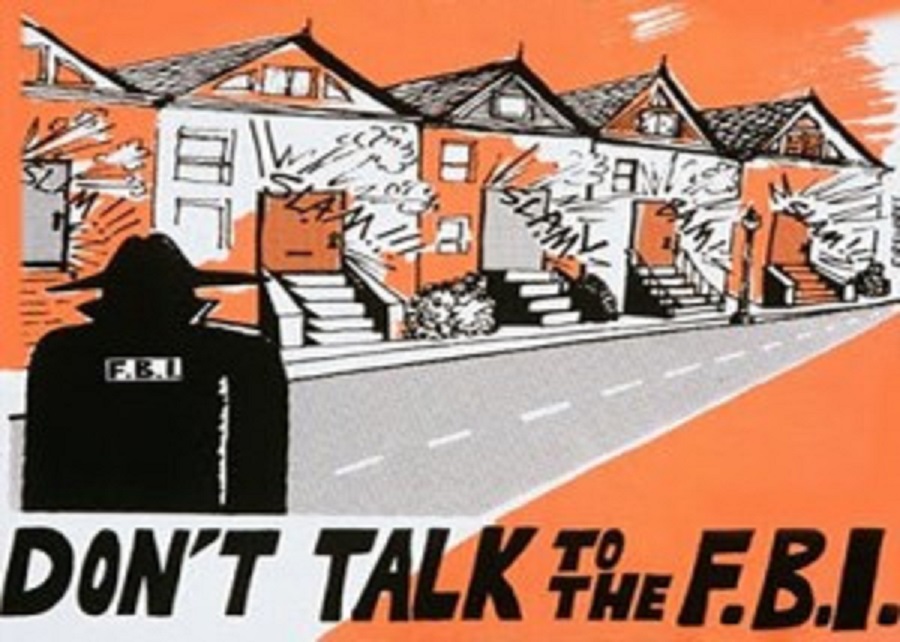

DGR, formed about four years ago, requires its members to adhere to what the group calls a “security culture” in order to reduce the amount of paranoia and fear that often comes with radical activism. On its website, DGR explains why it is important not to talk to police agents: “It doesn’t matter whether you are guilty or innocent. It doesn’t matter how smart you are. Never talk to police officers, FBI agents, Homeland Security, etc. It doesn’t matter if you believe you are telling police officers what they already know. It doesn’t matter if you just chit chat with police officers. Any talking to police officers, FBI agents, etc. will almost certainly harm you or others.”

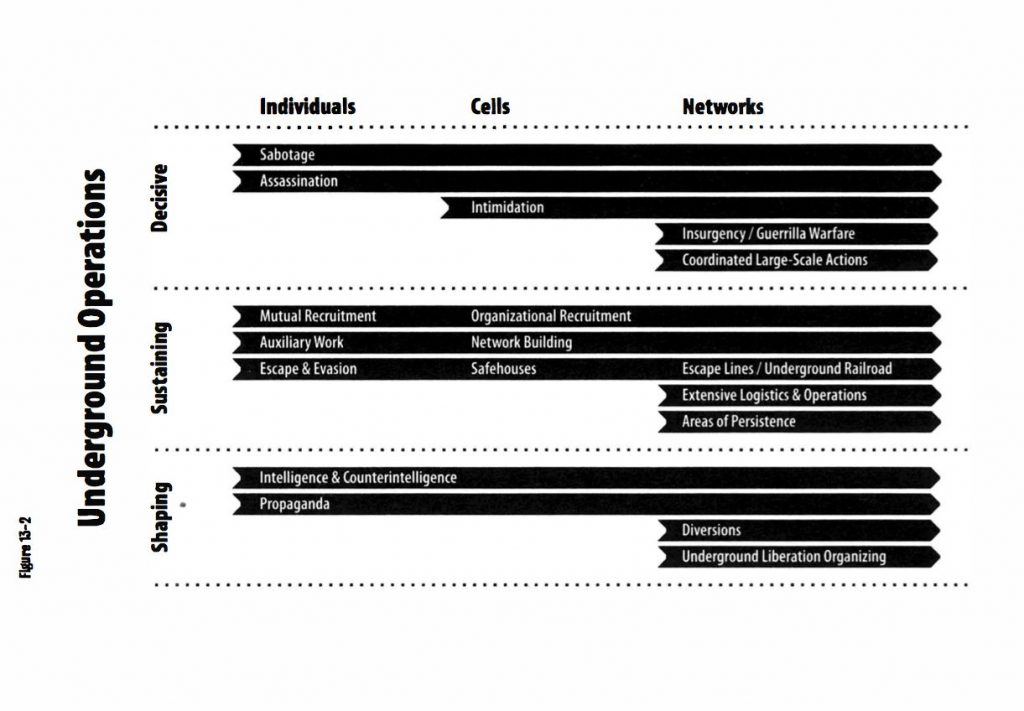

Keith, along with Derrick Jensen and Aric McBay, co-authored a book published in 2011, Deep Green Resistance, on which the DGR group is largely based. DGR describes itself as an “aboveground organization that uses direct action in the fight to save our planet.” On its website, DGR states there is a need for a separate “underground that can target the strategic infrastructure of industrialization.”

In the “Deep Green Resistance” book, the authors ask, “What if there was a serious aboveground resistance movement combined with a small group of underground networks working in tandem?”

“[T]he undergrounders would engage in limited attacks on infrastructure (often in tandem with aboveground struggles), especially energy infrastructure, to try to reduce fossil fuel consumption and overall industrial activity,” the authors write in the book. “The overall thrust of this plan would be to use selective attacks to accelerate collapse in a deliberate way, like shoving a rickety building.”

In speeches and writings, Jensen, a co-leader of DGR, often ponders this question: “Every morning when I wake up I ask myself whether I should write or blow up a dam.” He also has argued about the necessity of using any means necessary “to stop this culture from killing the planet.” Jensen said he has not been questioned by the FBI about his involvement with DGR. He is also unaware of any DGR members who have been arrested for their work with the group.

In late 2014 and early 2015, the FBI contacted about a dozen DGR members either by telephone or through in-person visits. Max Wilbert, a professional photographer and one of the founding members of DGR, said the FBI contacted him on his cell phone during this period. “I immediately said that I wasn’t going to answer any questions and hung up the phone,” Wilbert told CounterPunch. “This is the best way to deal with this sort of government repression. As soon as they know that you will answer questions, they will keep coming after you.” If activists refuse to answer questions, the FBI or other police agencies are more likely to leave the person alone, he said.

In September 2015, Wilbert was among a group of DGR members detained at the U.S.-Canada border as they were on their way to attend a speech by author Chris Hedges in Vancouver, British Columbia. The group was eventually denied entry into Canada.

Wilbert said the Canadian border guards seemed to be searching for a reason to deny the DGR members entry. After focusing on some women’s self-defense gear in the car (some people in the vehicle were planning to offer a free class on self-defense in British Columbia), the border guards’ questions started turning to each person’s activism.

Making sure he was honest with the officers, Wilbert told the Canadian border guards that he had volunteered to take photographs of Hedges’ scheduled speech. “They said that they suspected I was entering the country to work illegally,” he said.

After getting turned back by the Canadian guards, the vehicle’s occupants faced additional scrutiny by U.S. border agents. At the U.S. border, the questions became much more political in nature. The U.S. guards asked Wilbert and his colleagues about the groups they belonged to and the ideas that these groups promoted. “Officers from the Canadian side even came over and spoke with the U.S. officers about us,” he said.

U.S. border guards confiscated Wilbert’s laptop computer. “Under U.S. law, they can legally copy your entire hard drive and keep the contents for something like 30 days,” he said. After a few hours, the border guards returned the computer. But Wilbert chose to get rid of the laptop after the search because he was concerned the government agents had tampered with it.

The Department of Homeland Security also has demonstrated an interest in the environmental group. DGR member Deanna Meyer, who lives in Colorado, was asked by a DHS agent during a visit to her home if she would be interested in “forming a liaison,” according to a July 6, 2015, article in Earth Island Journal. The agent reportedly told Meyer he wanted to “head off any injuries or killing of people that could happen by people you know.” Meyer refused to cooperate with the DHS agent.

Wilbert views the federal police agencies’ ongoing actions against DGR members as harassment and intimidation. “It makes a mockery of free speech and democracy. We may advocate for radical and revolutionary ideas, but our work is legal. We are nonviolent. We are peaceful people,” he said.

The federal government’s treatment of DGR members is similar in some ways to how political activists were treated during the Red Scare era of the 1950s, contended Wilbert. A relative of blacklisted Hollywood screenwriter Dalton Trumbo is a member of DGR and a friend of Wilbert’s. Her childhood was marked by government surveillance, blacklisting and intimidation, he said. Pointing to Dalton Trumbo and other victims of the McCarthyite period, Wilbert emphasized these tactics are not new.

“This government uses intimidation and violence because these tactics are brutally effective. For me and the people I work with, we expect pushback,” Wilbert said. “That doesn’t make it easy, but in a way, this sort of attention validates the fact that our strategy represents a real threat to the system of power in this country. They’re scared of us because we have a plan to hit them where it hurts.”

The police scrutiny of DGR members is continuing at the same time local and federal police agencies maintain a hands-off approach to the takeover of a federal government installation in eastern Oregon by an armed right-wing militia. Some of the militia members claim they would be willing to kill if police attempted to end their occupation of the federal wildlife refuge.

If environmental activists staged an armed occupation of a coal-fired power plant, coal export terminal, or hydroelectric facility in the Western United States, they would be subject to an intense and immediate response by police agencies, Wilbert said. “The federal government doesn’t really give a damn, by and large, about what happens in the open West, at least when it’s wealthy white people doing the occupying,” he said. “But any occupation that actually threatened their power would see swift retribution. That is one of the main jobs of the police: to protect the rich and business interests against the people.”

DGR has learned that the “Deep Green Resistance” book is part of the FBI’s library at the agency’s offices in Quantico, Va. “They’re definitely aware of us. We have filed a Freedom of Information Act request to find out what kind of information the FBI is gathering,” Wilbert said. “But those requests were denied because they involve active investigations.”

When FBI agents visited her home in Pittsburgh, Neffshade said she felt fear during the questioning. She tried to remain calm. “I felt pressure to respond to their questions because, hey, I’ve been taught that it’s rude to just stand in silence when someone is speaking to you,” she explained. “I maintained silence long enough to gather my thoughts about which phrases are appropriate to say to law enforcement. After they left, I felt shaky and had to fight off feelings of paranoia.”

Before they left, the FBI agents handed Neffshade a business card and said, “If you change your mind, here is contact information.” Neffshades immediately contacted members of DGR to let them know the FBI had showed up on her doorstep.

While the FBI visit will make her more careful about what she writes in letters to prisoners, Neffshade said she has no plans to retreat from her involvement with DGR.

Mark Hand has reported on the energy industry for more than 25 years. He can be found on Twitter @MarkFHand.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Jun 22, 2015 | Building Alternatives, Gender, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. The first part of this interview is available here, and the second part here.

Time is Short: You mentioned some problems of radical groups—lack of respect for women and lack of a strategy. Could you expand on that?

Michael Carter: Sure. To begin with, I think both of those issues arise from a lifetime of privilege in the dominant culture. Men in particular seem prone to nihilism; I certainly was. Since we were taught—however unwittingly—that men are entitled to more of everything than women, our tendency is to bring this to all our endeavors.

I will give some credit to the movie “Night Moves” for illustrating that. The men cajole the woman into taking outlandish risks and they get off on the destruction, and that’s all they really do. When an innocent bystander is killed by their action, the woman has an emotional breakdown. She’s angry with the men because they told her no one would get hurt, and she breaches security by talking to other people about it. Their cell unravels and they don’t even explore their next options together. Instead of providing or even offering support, one of the men stalks and ultimately kills the woman to protect himself from getting caught, then vanishes back into mainstream consumer culture. So he’s not only a murderer but ultimately a cowardly hypocrite, as well.

Honestly, it appears to be more of an anti-underground propaganda piece than anything. Or maybe it’s just a vapid film, but it does have one somewhat valid point—that we white Americans, particularly men, are an overprivileged self-centered lot who won’t hesitate to hurt anyone who threatens us.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

That’s a fictional example, but any female activist can tell you the same thing. And of course misogyny isn’t limited to underground or militant groups; I saw all sorts of male self-indulgence and superiority in aboveground circles, moderate and radical both. It took hindsight for me to recognize it, even in myself. That’s a central problem of radical environmentalism, one reason why it’s been so ineffective. Why should any woman invest her time and energy in an immature movement that holds her in such low regard? I’ve heard this complaint about Occupy groups, anarchists, aboveground direct action groups, you name it.

Groups can overcome that by putting women in positions of leadership and creating secure, uncompromised spaces for them to do their work. I like to reflect on the multi-cultural resistance to the Burmese military dictatorship, which is also a good example of a combined above- and underground effort, of militant and non-violent tactics. The indigenous people of Burma traditionally held women in positions of respect within their cultures, so they had an advantage in building that into their resistance movements, but there’s no reason we couldn’t imitate that anywhere. Moreover, if there are going to be sustainable and just cultures in the future, women are going to be playing critical roles in forming and running them, so men should be doing everything possible to advocate for their absolute human rights.

As for strategy, it’s a waste of risk-taking for someone to cut down billboards or burn the paint off bulldozers. It’s important not to equate willingness with strategy, or radicalism and militancy with intelligence. For example, I just noticed an oil exploration subcontractor has opened an office in my town. Bad news, right? I had a fleeting wish to smash their windows, maybe burn the place down. That’ll teach ‘em, they’ll take us seriously then. But it wouldn’t do anything, only net the company an insurance settlement they’d rebuild with and reinforce the image of militant activists as mindless, dangerous thugs.

If I were underground, I’d at least take the time to choose a much more costly and hard-to-replace target. I’d do everything I could to coordinate an attack that would make it harder for the company to recover and continue doing business. And I’d only do these things after I had a better understanding of the industry and its overall effects, and a wider-focused examination of how that industry falls into the mechanism of civilization itself.

By widening the scope further, you see that ending oil and gas development might better be approached from an aboveground stance—by community rights initiatives, for example, that have outlawed fracking from New York to Texas to California. That seems to stand a much better chance of being effective, and can be part of a still wider strategy to end fossil fuel extraction altogether, which would also require militant tactics. You have to make room for everything, any tactic that has a chance of working, and begin your evaluation there.

To use the Oak Flat copper mine example, now the mine is that much closer to happening, and the people working against it have to reappraise what they have available. That particular issue involves indigenous sacred sites, so how might that be respectfully addressed, and employed in fighting the mine aboveground? Might there be enough people to stop it with civil disobedience? Is there any legal recourse? If there isn’t, how might an underground cell appraise it? Are there any transportation bottlenecks to target, any uniquely expensive equipment? How does timing fit in? How about market conditions—hit them when copper prices are down, maybe? Target the parent company or its other subsidiaries? What are the company’s financial resources?

An underground needs a strategy for long-term success and a decision-making mechanism that evaluates other actions. Then they can make more tightly focused decisions about tactics, abilities, resources, timing, and coordinated effort. The French Resistance to the Nazis couldn’t invade Berlin, but they sure could dynamite train tracks. You wouldn’t want to sabotage the first bulldozer you came across in the woods; you’d want to know who it belonged to, if it mattered, and that you weren’t going to get caught. Maybe it belongs to a habitat restoration group, who can say? It doesn’t do any good to put a small logging contractor out of business, and it doesn’t hurt a big corporation to destroy machinery that is inexpensive, so those questions need to be answered beforehand. I think successful underground strikes must be mostly about planning; they should never, never be about impulse.

TS: There are a lot of folks out there who support the use of underground action and sabotage in defense of Earth, but for any number of reasons—family commitments, physical limitations, and so on—can’t undertake that kind of action themselves. What do you think they can do to support those willing and able to engage in militant action?

MC: Aboveground people need to advocate underground action, so those who are able to be underground have some sort of political platform. Not to promote the IRA or its tactics (like bombing nightclubs), but its political wing of Sinn Fein is a good example. I’ve heard a lot of objections to the idea of advocating but not participating in underground actions, that there’s some kind of “do as I say, not as I do” hypocrisy in it, but that reflects a misunderstanding of resistance movements, or the requirements of militancy in general. Any on-the-ground combatant needs backup; it’s just the way it is. And remember that being aboveground doesn’t guarantee you any safety. In fact, if the movement becomes effective, it’s the aboveground people most vulnerable to harm, because they’re going to be well known. In that sense, it’s safer to be underground. Think of the all the outspoken people branded as intellectuals and rounded up by the Nazis.

The next most important support is financial and material, so they can have some security if they’re arrested. When environmentalists were fighting logging in Clayoquot Sound on Vancouver Island in the 1990s, Paul Watson (of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society) offered to pay the legal defense of anyone caught tree spiking. Legal defense funds and on-call pro-bono lawyers come immediately to mind, but I’m sure that could be expanded upon. Knowing that someone is going to help if something horrible happens, combatants can take more initiative, can be more able to engineer effective actions.

We hope there won’t be any prisoners, but if there are, they must be supported too. They can’t just be forgotten after a month. As I mentioned before, even getting letters in jail is a huge morale booster. If prisoners have families, it’s going to make a big difference for them to know that their loved ones aren’t alone and that they will have some sort of aboveground material support. This is part of what we mean when we talk about a culture of resistance.

TS: You’ve participated in a wide range of actions, spanning the spectrum from traditional legal appeals to sabotage. With this unique perspective, what do you see as being the most promising strategy for the environmental movement?

MC: We need more of everything, more of whatever we can assemble. There’s no denying that a lot of perfectly legal mainstream tactics can work well. We can’t litigate our way to sustainability any more than we can sabotage our way to sustainability; but for the people who are able to sue the enemy, that’s what they should be doing. Those who don’t have access to the courts (which is most everyone) need to find other roles. An effective movement will be a well-organized movement, willing to confront power, knowing that everything is at stake.

Decisive Ecological Warfare is the only global strategy that I know of. It lays out clear goals and ways of arranging above- and underground groups based on historical examples of effective movements. If would-be activists are feeling unsure, this might be a way for them to get started, but I’m sure other plans can emerge with time and experience. DEW is just a starting point.

Remember the hardest times are in the beginning, when you’re making inevitable mistakes and going through abrupt learning curves. When I first joined Deep Green Resistance, I was very uneasy about it because I still felt burned out from the ‘90s struggles. What I’ve discovered is that real strength and endurance is founded in humility and respect. I’ve learned a lot from others in the group, some of whom are half my age and younger, and that’s a humbling experience. I never really understood what a struggle it is for women, either, in radical movements or the culture at large; my time in DGR has brought that into focus.

Look at the trans controversy; here are males asking to subordinate women’s experiences and safe spaces so they can feel comfortable. It’s hard for civilized men to imagine relationships that aren’t based on the dominant-submissive model of civilization, and I think that’s what the issue is really about—not phobia, not exclusionary politics, but rather role-playing that’s all about identity. Male strength traditionally comes from arrogance and false pride, which naturally leads to insecurity, fear, and a need to constantly assert an upper hand, a need to be right. A much more secure stance is to recognize the power of the earth, and allow ourselves to serve that power, not to pretend to understand or control it.

TS: We agree that time is not on our side. What do you think is on our side?

TS: We agree that time is not on our side. What do you think is on our side?

MC: Three things: first, the planet wants to live. It wants biological diversity, abundance, and above all topsoil, and that’s what will provide any basis for life in the future. I think humans want to live, too; and more than just live, but be satisfied in living well. Civilization offers only a sorry substitute for living well to only a small minority.

The second is that activists now have a distinct advantage in that it’s easier to get information anonymously. The more that can be safely done with computers, including attacking computer systems, the better—but even if it’s just finding out whose machinery is where, how industrial systems are built and laid out, that’s much easier to come by. On the other hand the enemy has a similar advantage in surveillance and investigation, so security is more crucial than ever.

The third is that the easily accessible resources that empires need to function are all but gone. There will never be another age of cheap oil, iron ore mountains, abundant forest, and continents of topsoil. Once the infrastructure of civilized humanity collapses or is intentionally broken, it can’t really be rebuilt. Then humans will need to learn how to live in much smaller-scale cultures based on what the land can support and how justly they treat one another. That will be no utopia, of course, but it’s still humanity’s best option. The fight we’re now engaged in is over what living material will be available for those new, localized cultures—and more importantly, the larger nonhuman biological communities—to sustain themselves. What polar bears, salmon, and migratory birds need, we will also need. Our futures are forever linked.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Mar 8, 2015 | Property & Material Destruction, Repression at Home, Strategy & Analysis

In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. Due to the length of the interview, we’ve presented it in three installments; go to Part II here, and Part III here.

Time is Short: Can you give a brief description of what it was you did?

Michael Carter: The significant actions were tree spiking—where nails are driven into trees and the timber company warned against cutting them—and sabotaging of road building machinery. We cut down plenty of billboards too, and this got most of the media attention. We did this for about two years in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, about twenty actions. My brother Sean was also indicted. The FBI tried to round up a larger conspiracy, but that didn’t stick.

TS: How did you approach those actions? What was the context?

MC: We didn’t know a lot about environmental issues or political resistance, so we didn’t have much understanding of context. We had an instinctive dislike of clear cuts, and we had the book The Monkey Wrench Gang. Other people were monkeywrenching, that is, sabotaging industry to protect wilderness, so we had some vague ideas about tactics but no manual, no concrete theory. We knew what Earth First! was, although we weren’t members. It was a conspiracy only in the remotest sense. We had little strategy and the actions were impetuous. If we’d been robbing banks instead, we’d have been shot in the act.

Nor did we really understand how bad the problem was. We thought that deforestation was damaging to the land, but we didn’t get the depth of its implications and we didn’t link it to other atrocities. We just thought that we were on the extreme edge of the marginal issue of forestry. This was before many were talking about global warming or ocean acidification or mass extinction. It all seemed much less severe than now, and of course it was. The losses since then, of species and habitat and pollution, are terrible. No monkeywrenching I know of did anything significant to stop that. It was scattered, aimed at minor targets, and had no aboveground political movement behind it.

Clearcuts in the Swan Valley, MT near Loon Lake on the slope of Mission Mountains. Photo by George Wuerthner.

TS: What was the public response to your actions?

MC: They saw them as vandalism, mindlessly criminal, even if they were politically motivated. This was before 9/11, before the Oklahoma City bombing; the idea of terrorism wasn’t so powerful, so our actions weren’t taken nearly as seriously as they would be now.

We were charged by the state of Montana with criminal mischief and criminal endangerment. The state’s evidence was solid enough we thought we couldn’t win a trial, so we pled guilty on the chance the judge wouldn’t send us to prison. Our defense was to say, “We’re sorry we did it, it was motivated by sincerity but it was dumb.” And that was true. We were able to get our charges reduced from criminal endangerment to criminal mischief. I got a 19 year suspended prison sentence, Sean got 9 years suspended. We both had to pay a lot of money, some $40,000, but I only spent three months in county jail and Sean got out of a jail sentence altogether. We were lucky.

TS: As you said, this was before the obsessive fear of terrorism. How do you think that played into your trial and indictment, and how do you think it would be different today?

MC: Had it happened after any big terrorism event, they would have sent us to prison, there’s no doubt about that. States have to maintain a level of constant fear and prove themselves able to protect citizens.

The irony was, I’m not sure I wanted to be serious—there seemed to be something protective in not being all that effective, in being intentionally quixotic, in being a little cute about it. There was a particularly comical aspect to cutting down billboards, and that was helpful only when I was arrested. It made it look less like terrorism and more like reckless things I did when I was drunk, and a lot of people approved of it because they thought billboards were tacky. I want to emphasize that cutting down billboards is nothing I’d advise anyone to consider, only that a little bit of public approval made a surprising difference to my morale, and may have positively influenced sentencing. But the point, of course, is to be effective and not get caught in the first place. These days, if someone gets caught in underground actions, they will be in a lot more trouble than ever before.

TS: How did you get caught?

We left fingerprints and tire tracks, we rented equipment under our own names—like an acetylene torch used to cut down steel billboard posts—and we told people who didn’t need to know about it. We assumed we were safe if they didn’t catch us in the act and because our fingerprints weren’t on file, and we couldn’t have been more wrong. The cops can subpoena anyone’s fingerprints, and use that evidence for something in the past. The importance of security can’t be overstated—and we didn’t have any. Even with a couple rudimentary precautions, we might have saved ourselves the whole ordeal of getting caught. If we’d read the security chapter of Dave Foreman’s book Ecodefense, I don’t think we would have even come under suspicion. Anyone taking any action, above- or underground, needs to take the time to learn security well.

It’s not just saving yourself the anguish of arrest and prison time. If you’re rigorous about security, you might be able to have a real chance at changing how the future of the planet plays out. You can have no impact at all in a jail cell. In our case, we definitely could have stopped timber sales with tree spiking even though that tactic was extremely unpopular politically. It was seen as an act of violence against innocent lumber mill workers instead of a preventative measure to protect forests. The dilemma never got past that stage, though. We had little chance of having any reasoned tactical considerations—let alone making reasoned decisions—because we were always a little too afraid of being caught. With good reason, it turns out.

TS: What have you learned from your experience? Looking back on what you did all those years ago, what’s your perspective on your actions now? Is there anything you would have done differently?

MC: Well I definitely would have taken steps to not get caught. I would have picked my targets more carefully, and I would have entered into an understanding with myself that while my enemy is composed of people, it’s only a system, inhuman and relentless. It can’t be reasoned with; it has no sanity, no sense of morality, no love of anything. Its job is to consume. I would have tried to focus on that guiding fact, and not on the people running it or who were dependent on it. I would have tried to find the weaknesses in the system, and then attacked those.

I’d have tried not to allow my emotions to dictate my strategy or actions. Emotions might get me there in the first place—I don’t think you could get to such a desperate point without a strong emotional response—but once I arrived at the decision to act, I would have done everything I could to think like a soldier, find a competent group to join with, and pick expensive and hard-to-replace targets.

TS: I assume you didn’t just wake up one day and decide to attack bulldozers and billboards. What was your path from being apolitical to having the determination and the passion to do what you did?

MC: When I was struggling with high school, my brother loaned me a stack of Edward Abbey books, which presented the idea that wilderness is the real world, precious above all else. The other part was living in northwest Montana, where you see deforestation anywhere you look. You can’t not notice it, and there’s something about those scalped hills and skid trails and roads that triggers a visceral, angry response. It’s less abstract than atmospheric carbon or drift-net fishing. You don’t see those things the way you see denuded mountainsides. My family heated the house with wood, and we would sometimes get it out of slash piles in the middle of clearcuts. I had lots of firsthand exposure to deforested land. I wondered why the Sierra Club didn’t do something about it, how it could be allowed. We would occasionally go to Canada, and it was even worse up there. No one can feel despair like a teenager, and I had it in spades. If Greenpeace won’t stop this, I reasoned, well then I will.

I started building an identity around this, though, and that’s disastrous for a person choosing underground resistance. You naturally want others to know and appreciate your feelings and accomplishments, especially when you’re young, but the dilemma underground fighters face is that they must present another, blander identity to the world. That’s hard to do.

TS: You were fairly isolated in your actions, and you’ve emphasized the importance of a larger context. Do you see those two ideas connecting? Do you think saboteurs should be acting in a larger movement?

MC: I think saving the planet relies completely on the coordinated actions of underground cells coupled with an aboveground political movement that isn’t directly involved in underground actions. When I was underground, I had no hope of building a network, mostly because of a lack of emotional and political maturity. I also didn’t have the technological or strategic savvy, or a means of communicating with others. The actions themselves were mostly symbolic, and symbolic actions are a huge waste of risk. They’re a waste of political capital too. Most everyone is going to disagree with underground activism and it’s not going to change anyone’s mind about the policy issue—hardly anything will—so it has to count in the material realm. If people are ready and willing to risk their lives and their freedom then they should fight to win, not just to make some sort of abstract point.

TS: After you were arrested, what support—if any—did you receive from folks on the outside, and what support would you have wanted to receive?

MC: The most important support was financial, but there wasn’t a lot of it. Our plea bargain didn’t guarantee we wouldn’t go to prison. We were also worried that the feds would indict us for racketeering, an anti-Mafia charge with serious minimum sentencing. If we’d had more legal defense financing we’d of course have felt a lot more secure, but twenty years of reflection tells me we didn’t really deserve it considering how poorly we executed the actions, what little effect they caused.

That sounds like I’m being awfully hard on myself, and hindsight is always 20/20, but the point is that a legal crisis is exhausting and expensive. Your community will question whether your actions are worthy of the price they’ll have to pay if you’re caught. My actions were not.

Even so, I appreciated any sort of support. Hearing from the outside in jail is better than you’d believe. A lot of Earth First! Journal readers sent me anonymous letters. I wrote back and forth with one of the women who was jailed for noncooperation with a federal grand jury investigating the Animal Liberation Front in Washington. Seeing approving letters to the editor in the papers was also great. Just knowing that the whole world isn’t your enemy, that someone is thinking about you and appreciates what you did, is priceless.

Artwork by Stephanie McMillan

TS: Do you still think militant and illegal forms of direct action and sabotage are justified? Why?

MC: I do, yes. In an ideal world I don’t think violence is the best way to accomplish anything, but obviously this isn’t an ideal world. Our circumstances are getting worse and worse—overpopulation, pollution, oceanic dead zones, you name it—and any options for a decent and dignified future for humanity are dwindling day by day, so what choice does that leave us? Individual attempts at sustainable living won’t work so long as the industrial system is running. The dismantling of infrastructure is the most important missing piece right now. It’s where the system is most vulnerable, so it should be employed right away. It can be effective, but it has to be responsible, careful, and extraordinarily smart.

One of the reasons underground political actions are so unpopular is that they’re always presented as attacks on individuals, rather than on a system. I think it’s important to reframe sabotage as strikes on an unjust, destructive system, and that civilization is not us, and not the highest expression of human endeavor, but only an idea. Civilization is masquerading as humanity, but that’s not what it is. Civilization is only one sort of cultural plan, a way of creating unsustainably large human settlements, based entirely on agriculture which itself is completely unsustainable.

The argument that militant actions are counterproductive has a little bit of merit because the scale they’ve happened on hasn’t been large enough to have any impact. For example, the Earth Liberation Front burning SUV’s. You’re left with the political fallout, the mainstream activists distancing themselves and all the other bad stuff that comes with it, but you don’t have any measurable gain, in reducing carbon emissions, say. Sabotage needs to happen on a larger scale, against more expensive targets, to be impactful. Fighters need to think big. That’s how militaries accomplish their goals—by acting against systems. They blow up bridges, they take out buildings, they disable the enemy arsenal, they kill the enemy—that’s how they function. I agree activists don’t want to identify with militarism, but it’s foolhardy to not consider what’s actually going to get the job done, and militaries know how to do that. No moral code will matter if the biosphere collapses. Doctrinal non-violence isn’t going to have any relevance in a world that’s 20 degrees hotter than it is now.

I wish an effective movement could be nonviolent, but we just don’t have enough social cohesion to orchestrate that kind of thing. There’s so few of us who give a shit, and we’re scattered, isolated, and disenfranchised. We don’t have adequate numbers, influence, or power, and I don’t see that changing. Everywhere we look we’re losing, because we don’t have a movement that can say, “No. You’re not going to do that. We will stop this, whatever it takes,” and back that up. Aboveground activists need to advocate a lesser evil, to continually pose the question of what is worse: that some property was destroyed, or that sea shells are dissolving in acid oceans? Underground activists need to act that out. It’s not a rhetorical question.

We need to remember, too, that small numbers of people can engineer profound changes when their actions are wisely leveraged. Very few took part in the resistance movements of World War II, but they made all the difference to ultimately defeating the Axis.

Interview continues here.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

by DGR News Service | Oct 7, 2014 | Repression at Home

By Deep Green Resistance Steering Committee

Recently, persons working for the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Joint Terrorism Task Force have contacted multiple DGR members by phone and in-person visits to their homes. These agents attempted to get members to talk about their involvement with DGR, have asked for permission to enter members’ homes, and contacted members’ families.

DGR strategy and community rests upon a diligent adherence to security culture – a set of principles and behavior norms meant to help increase the safety of resistance communities in the face of state repression. All members are required to review and agree to our guidelines upon requesting membership, and we routinely hold org-wide refresher calls to remind everyone. We understand that while these guidelines can help increase our safety from state repression, unfortunately we cannot ever guarantee complete protection.

DGR is strictly an aboveground organization. As per our code of conduct, our members do not engage in underground or extra-legal tactics, and any member who violates our code of conduct forfeits their DGR membership. We advocate for a strategy that can effectively address the converging threats to the living world. Such a strategy is a threat to the ruling system, and state repression should be expected. DGR is dedicated to remaining effective while also doing all we can to increase member safety. We will not be intimidated into compromising our work, and we remain committed to amplifying the voice of resistance against injustice and ecocide.

Read our security culture guidelines.