by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 9, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy, Lobbying, Mining & Drilling

By Hannibal Rhoades / Intercontinental Cry

After five years of legal contests and uncertainty, the Colombian Constitutional Court has confirmed that Yaigojé Apaporis, an indigenous resguardo (a legally recognized, collectively owned territory), also has legitimate status as a national park.

The decision is cause for celebration for Indigenous Peoples who call the region home. But it is less welcome news for Canadian multinational mining corporation Cosigo Resources, the company contesting the area’s national park status. The court’s ruling immediately and indefinitely suspends all mining activities in the park, including Cosigo’s license to mine gold from one of Yaigojé’s most sacred areas.

In the broader context of Colombia’s push to expand mining activities in the name of development, the court’s decision is seen as a significant precedent.

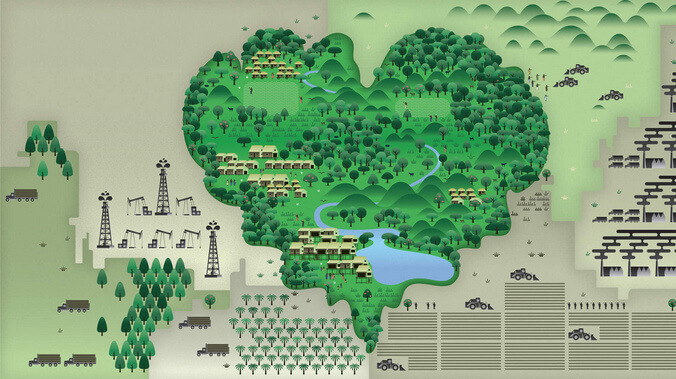

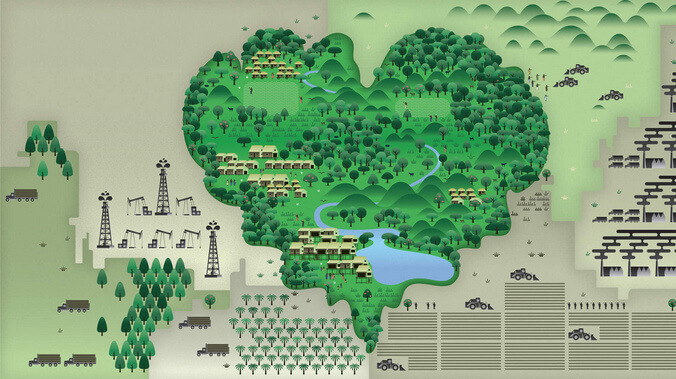

Since the 1980s, Colombia has protected more than 24 million hectares of the Amazon, placing an area the size of Britain back in the hands of its traditional owners. By choosing the rights of Indigenous Peoples and a new national park over multinational mining interests, the court’s decision safeguards Colombia’s achievements rather than undermining them.

THE BATTLE FOR YUISI’S GOLDEN LENS

Straddling Amazonas and Vaupés states, comprising a million hectares of the Northwestern Colombian Amazon, the pristine forest region of Yaigojé Apaporis is rich in both biological and cultural diversity.

The area hosts endangered mammals such as the giant anteater, jaguar, manatee and pink river dolphin. It is also home to the Makuna, Tanimuka, Letuama, Barasano, Cabiyari, Yahuna and Yujup-Maku Indigenous Peoples, who share a common cosmological system and rich shamanistic traditions. Together these populations act as Yaigojé’s guardians, a role that was strengthened in 1988 when, with the assistance of Colombian NGO Gaia Amazonas, they successfully established the Yaigojé Apaporis resguardo over their traditional territory. But this status has recently been tested.

Under Colombian law, a resguardo recognition grants its inhabitants collective ownership of and rights to the soil, but the subsoil remains in the control of the state and vulnerable to prospecting. With companies seeking to exploit this loophole, the Colombian Amazon has seen a tidal wave of mining interest since the mid-2000s, with the government declaring mining an “engine for development.”

Riding at the crest of this wave, in the late 2000s Canadian mining multinational Cosigo Resources made clear to local communities in Yaigojé its intention to mine for gold at a site within the resguardo known as La Libertad or Yuisi.

Local indigenous leaders say Cosigo became known to them when company representatives visited their malocas (traditional riverside houses). The indigenous leaders allege that officials offered them money in return for assurance of support the company to mine in Yuisi. These offers were rejected.

At Yuisi, a wide stretch of the Apaporis river cascades over rocks, forming roaring rapids. To the people of Yaigojé it is a vital sacred site, inextricably tied to their story of origin, identity and ability to care for the territory and the planet as a whole. Elders say “Yuisi is the crib of our way of thinking, of life and power. Everything is born here in thought: nature, the crops, trees, fruits, everything that exists, exists before in thought.”

Local shaman describe the gold and other minerals that form the bedrock of their territory as ‘lenses’ that allow them to see into the Earth, divine or diagnose any problems and correct them through rituals, prayer and thought. If gold were to be removed from Yuisi, they would lose their ability to cure and manage their territory as they have done for millennia. This is because an integral part of the territory itself would be lost. The notion that territory stops at the soil “as deep as the manioc’s root” is alien.

With negotiation with Cosigo out of the question, the traditional authorities in Yaigojé called an urgent congress of the Asociación de Capitanes Indígenas del Yaigojé Apaporis (ACIYA), an indigenous organization formed of groups living along the Apaporis River, in the area of Yaigojé that lies in Amazonas State. Having discussed the dangers posed by Cosigo’s presence and plans, ACIYA agreed that they must seek help from outside sources to further protect their territory.

“The best way to shield the territory was to call upon the state. In other words: Western disease is cured by Western medicine. If all mining licenses are given by the state, it is necessary to call on the state to defend the territory,” says Gerardo Macuna, a representative of ACIYA.

Advised that achieving national park status would extend protection to the subsoil, ACIYA and its supporters formally requested that the Colombian Government create a national park over their resguardo and traditional territory.

The people’s effort to add a third layer of protection for their territory was successful. In October 2009, Yaigojé Apaporis became Colombia’s 55th national protected area, but celebrations were short lived. Just two days after the area was awarded national park status, Cosigo Resources was granted a mining title for the Yuisi area, catalysing an epic struggle between Colombia’s will to protect the Amazon, with the help of indigenous inhabitants, or exploit it at their expense by prioritizing mining.

DEEP IN THE AMAZON, A SMOKING GUN

Despite having been granted a license, Yaigojé’s new status as a national park remained an obstacle to Cosigo. The national park status, and its accompanying legal protections for the subsoil, would need to be revoked before mining could begin.

Facing stiff opposition from both ACIYA and the Colombian National Parks authorities just as Cosigo appeared to be fighting an uphill battle, the company got what seemed an almost impossible stroke of luck. A few months after Yaigojé was declared a national park, members of indigenous organization ACITAVA from the region of Yaigojé lying in Vaupés State launched a legal challenge to Yaigojé’s status at the Colombian Constitutional Court. Led by a local settler named Benigno Perilla, the challengers said that they had not been fully or adequately consulted in the process of creating the national park and it therefore violated their right to Free Prior and Informed Consent.

With an apparently complex conflict unfolding between Yaigojé’s Indigenous Peoples and the area’s national park status–its ecological and social integrity held in the balance–a legal deadlock ensued. This situation persisted for three years, until January 2014, when in an unprecedented move, three judges from Colombia’s Constitutional Court made the decision to travel to the heart of the Colombian Amazon to hold a hearing and consult with communities first hand.

Jorge Iván Palacio, president of the court, explained the court’s decision to make the journey by stating that “there is no justice unless we know what they think in the communities.” The ensuing hearing thoroughly vindicated his observation.

Before 160 indigenous inhabitants from along the Apaporis River and the judges, Benigno Perilla publicly admitted that his and ACITAVA’s legal strategy was encouraged, organized and paid for by Cosigo Resources. In what would prove the critical turning point in the case, the indigenous members of ACITAVA who had supported the challenge made a public apology, said they had been misled and declared their support for the creation of the national park.

A NEW DAWN FOR INDIGENOUS-LED CONSERVATION

Although it has been more than another year coming, the Colombian Constitutional Court has ousted Cosigo and legitimized the declaration of Yaigojé Apaporis as a national park. The decision recognizes the authority of the area’s Indigenous Peoples and protects their fundamental rights to culture, identity and consultation.

The decision is regarded as a significantly positive precedent for future conflicts between mining operations, protected areas and their indigenous inhabitants, at a time when Colombia has declared mining to be in the national interest.

The judges found sufficient evidence of wrongdoing by Cosigo to ask Colombia’s Justice Minister to open an investigation into the company’s consultation processes and interactions with communities in the Yaigojé area. Recently published revisions to Colombia’s projects of national interest have seen Cosigo’s project removed from the list. The company is said to be reviewing its legal options.

Confirming the compatibility of indigenous resguardos and national parks, the court has also opened up the possibility for others to follow Yaigojé’s example and enhance the protection of their territories from destructive or unwanted “development.”

Since Yaigojé was declared a national park, and in spite of the legal wrangle over its future, ACIYA and local indigenous youths have been pioneering a powerful new conservation paradigm that values indigenous knowledge and places it at the root of national park management.

ACIYA’s work to find a method of conservation that both works for them and allows for close collaboration with Colombia’s national park authorities is the subject of a recent film and won the group the prestigious UNDP Equator Prize in 2014. Their approach stands in stark contrast to technocratic, neo-colonialist conservation norms founded on a misplaced belief in pristine, unmanaged wilderness. These have been criticized by Indigenous Peoples and rights groups for excluding and forcibly displacing indigenous communities, fencing them out of their own lands and so obstructing their right to practice their cultures.

As part of their program, 27 young indigenous leaders from nine communities in Yaigojé have engaged in a deep process of cultural research. Advised by their elders, they have documented, mapped and recorded their peoples’ traditional practices for safeguarding and conserving the forest. In the words of one researcher, the aim has been to “transmit traditional knowledge to the younger generations and protect our ancestral territory.” So far, they have succeeded in doing both.

The research produced by ACIYA will now be used to define the management of the Yaigojé Apaporis National Park, further legitimizing local indigenous knowledge systems that have protected the life-support capacities of this rainforest region for generation after generation.

“Indigenous people are the natural allies of the rainforest and the whole environmental movement,” says former director of Gaia Amazonas Martin Von Hildebrand. “They have the traditional knowledge, they are organized. We just need to support them with what they need to run their own territories.”

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 7, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy, The Solution: Resistance

By Intercontinental Cry

Territories of Life is a video toolkit with a purpose. It’s aim: to bring stories of resistance, resilience and hope to indigenous communities on the frontline of the global rush for land.

Produced by our friends at LifeMosaic, a non-profit based in Scotland, the Territories of Life toolkit consists of ten stories that were filmed in communities across Indonesia, Philippines, Guatemala, Ecuador, Colombia, Paraguay, Tanzania and Cameroon.

“The videos in the Territories of Life toolkit share inspirational stories of communities that are successfully organizing to defend their territories and their futures,” reads a press release from LifeMosaic. They include “The story of Maasai indigenous women in Tanzania who used awareness raising, protests and political pressure to lead a movement in defense of their territory; and the Misak indigenous people in Colombia who have developed and are carrying out their Plan de Vida, a long‐term vision for self-determined development.”

The toolkit also includes a few primers on land rights, land grabs, and common tactics that companies use to convince communities to accept and support their projects.

LifeMosaic goes on to say that, “The video toolkit and accompanying facilitators’ guide are intended to support indigenous peoples as they exercise their right to free, prior and informed consent; advocate for their rights; participate more actively in local spatial planning; and draw up village action plans for self‐determined development and for protecting their territories, forests and resources.”

It’s more than mere lip service. LifeMosaic is actively working with hundreds of local partners to facilitate the free distribution of Territories of Life to indigenous communities and supporting organizations around the world.

To order a copy of the toolkit, visit www.lifemosaic.net. If other groups request a DVD, LifeMosaic recommends a donation of $11 (£10). The videos can also be downloaded online at their website.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Sep 18, 2015 | Indigenous Autonomy

By Robin Llewellyn / Intercontinental Cry

Children of the Wounaan People easily find diversion in the abandoned basketball stadium of Buenaventura, the largest city on Colombia’s Pacific coast. Some chase pigeons that try to settle around the highest rows of seats, casually resting to look out over the surrounding rooftops to the islands of mangrove and forest that bar the view to the sea. Others jump skipping ropes as two siblings ride brightly-coloured toy ponies past the plastic sheeting beneath the bleachers that grant each family their privacy.

Displacement from their territory has exacted a cruel cost. Two children have died since their community of Unión Aguas Claras was forced to flee ten months ago: one year-old Neiber Cárdenas Pirza died while suffering diarrhoea and vomiting last December, then in June the community lost a two day-old baby.

According to one of the displaced Wounaan it is “all the chemicals” in their new life that are to blame, coupled with the inadequate diet provided by Colombian authorities that leave them vulnerable to sickness. The concrete structure of the basketball stadium is also less hygienic than the wooden homes in the territory they were forced to abandon, she said.

But to another Wounaan there lies a deeper cause:

It is not just the illnesses of the Occident that have made us so ill. It is because of spiritual sickness; because of the loss of our spirituality.

He claimed that the deadly sickness in June was foreseen by their shaman, who had been unable to predict whether it would kill an adult or a child.

The community was preparing for a ceremony the following day in which they would use their spirits to “see” how affairs stood in their territory that has lain abandoned for nine months.

The pressures against them had been manifesting for years, the Wounaan told IC, through the armed conflict, petrol exploration, and narco-trafficking.

“The area is very strategic: the river marks the frontier of the FARC and the paramilitaries, and is also the means by which the Army moves,” One Wounaan explained. “Now all of the Rio San Juan has become militarized.”

In 2008 there was a massacre of six indigenous people in our territory. By 2014 we realized that we couldn’t resist any longer; we couldn’t move in our territory for all the armed groups passing through, we had to stay in our houses.

By November 2014, the harassment was no longer confined to their wider territory. A Wounaan woman explained that, one day, “Six paramilitaries arrived and asked to sleep in the settlement but the community replied that they could not; we said that we reserve the right to say no to all armed groups.”

That evening the local head of the paramilitaries arrived to threaten the assembled community, warning them that their attitude could only work to turn over their territory to other armed groups. Fearful for their safety, the people of Unión Aguas Claras resolved to leave together. A total of 344 people–63 families–boarded boats before dawn and descended the San Juan River to where it joins the lower Calima River. From there, they reached the estuary and followed the coast to Buenaventura, where Colombian authorities placed them in a stadium that only recently became vacant. Shortly before the Wounaan’s arrival, it sheltered Afro-Colombian and campesino families displaced by clashes in Bajo Calima between the Armed Forces and BACRIM (“bandas criminales” – armed criminal bands mostly born out of officially disbanded right-wing paramilitary groups).

Not a single person from the community stayed back. Describing how the community fished and grew “yucca, bananas, pineapples… everything”, one Wounaan lamented, “Now there will be nothing left of our farms; back there in our territory everything will be destroyed.”

When they were in their territory, all the women would gather every two months to prepare and weave threads extracted from the Werregue Palm into baskets and handicrafts that they would sell. The community would hold meetings to arrange days of minga, collective communal work that could involve tidying the territory or arranging the sewing of seeds in their farms. They also said that they carefully guarded their culture, one person stating unequivocally that, “He who does not speak Wounaan is not a Wounaan.”

The Wounaan language is now spoken in many of Colombia’s biggest cities, including Bogota, Medellin and Cali, where many Wounaan end up after being cleared from their homelands in the Pacific regions of the Valle del Cauca and Choco departments. Throughout 2014, Colombia’s National Victims’ Unit recorded 97,453 cases of forced displacement, with the Pacific region among the most impacted.

Wellington Carneiro of Buenaventura’s UNHCR office says there have been “several displacements of indigenous Wounaan communities [including] Balsalito, Chachajo, Chamapuro, Buenavista, Tio Cirilio, and Agua Clara, and recently the Papayo community. In total more than 1000 people have been displaced from the Lower San Juan River.”

The identity of the groups fighting for control of the San Juan and Calima waterways is unclear. The local authorities in Buenaventura initially responded to the community’s arrival by claiming there had been no need for the Wounaan’s displacement, and their territory was safe for their return.

However, according to Carneiro,

The Lower San Juan river is strategic to armed groups due to the access to the sea and for the trafficking of weapons and drugs. Also, with the tighter security implemented around the port of Buenaventura, the routes through the San Juan delta became more attractive. There are several groups disputing the control of the area apart from the Colombian Navy. This…puts the population under the pressure of armed groups for information and through restrictions to their mobility and other threats in the context of a disputed military control over the area.

Colombia has been wracked by a conflict between two competing drug-trafficking networks – the rising Urabeños and the declining Rastrojos – who each seek to monopolize the transport of cocaine via the Pacific coast. Confronted by a stubborn Rastrojos presence in Cali and Buenaventura, the Calima and San Juan rivers have become more strategic as the San Juan is fed by the Capomá river that provides a route into the Colombian interior.

The area has also seen BACRIM and guerrilla groups diversify their enterprises through illegal mining, timber, and agriculture. According to one of the displaced Wounaan, such activities of illegal armed groups are only one aspect of a broader war against indigenous territories across Colombia. He also warned that this broader conflict will not cease with the possible signing of a peace accord between the government and FARC guerrillas.

We will continue to face war. It may be a war without lead against the indigenous – a psychological war, a cultural war, or possibly also a physical war… We know that the peace process will open the way for megaprojects that will bring international investments into our territory, therefore we know that true peace will not come. For indigenous peoples the violence will not end with the peace process. The peace process will not resolve anything for us.

The peace negotiations have been proceeding in Havana, Cuba, despite the intense opposition of former president Alvaro Uribe and his powerful Centro Democratico party. An agreement is expected to be announced in the coming months, to be followed by a reworking of the country’s 1991 Constitution.

Another Wounaan commented,

Uribe has proposed that constitutional reform should proceed and constitutional reform will likely follow a peace accord. Indigenous people are totally unprepared and un-mobilized to participate in the process of rewriting the Constitution: we need to organize ourselves to shape this process.

The aims of the Centro Democratico are clear in the Septima Dia broadcasts of Caracol, which are so aggressive against indigenous people, because Centro Democratico wants to exterminate the indigenous movement.

Earlier this year, Caracol, one of Colombia’s leading private TV channels, broadcast a series under its Septima Dia weekly format on Colombia’s Indigenous Peoples, called Disharmonization: the Arrow of the Conflict. The controversial series attacked indigenous justice systems and claimed that indigenous authorities took massacre compensation from their intended recipients, an allegation that was debunked. The series also insinuated that indigenous institutions were supportive of FARC guerrillas, something that Colombian journalist Cesar Gaviria described as but one falsehood in a series “plagued by investigative and journalistic failures”.

Indigenous Nasa activists seeking to recover the La Emperatriz sugar plantation “from its rightful owners” were among those targeted by the series which also served as a platform for Centro Democratico’s Paloma Valencia, who advocates dividing the department of Cauca into two: “One for the indigenous for them to do their strikes, their demonstrations, and their invasions. And one directed towards development where we can have roads, promote investment and where there are dignified jobs for the Caucanos.”

Henry Caballero Fula of the Peace Commission of the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC) has written that the four aims of the Septima Dia broadcasts were to spread the views that:

Indigenous autonomy is something negative; it only helps to corruptly enrich some members, while harming the community in general and the non-indigenous sectors.

It was a mistake for the right to prior consultation to be integrated into the Colombian Constitution since it harms national development.

The indigenous justice system is another mistake in the Colombian Constitution: it is applied against the community and is the base of impunity and immunity for indigenous criminals.

Indigenous people receive many benefits and these are generating breakdown and corruption.

The trajectory of such arguments in Colombia’s current political climate are a pressing danger to Indigenous Peoples, according to the displaced Wounaan who are politically active through the Regional Indigenous Organization of Valle del Cauca (ORIVAC).

On Sept. 15, Feliciano Valencia of Cauca’s Nasa people, one of the most visible indigenous leaders in Colombia, who had addressed delegates of the displaced Wounaan at an ORIVAC conference, was abruptly arrested and imprisoned on charges that were previously dismissed in 2011. The charges stemmed from a 2008 controversy in which an undercover soldier–who had been exposed infiltrating a peaceful protest–was held subject to indigenous justice mechanisms. The CRIC argues that indigenous jurisdiction forms part of the 1991 Constitution, and that the imprisonment of Valencia is a “coup by the state against our Constitutional rights, and revokes the peace treaty that the Constitution of ’91 represents in our history.”

These developments hadn’t yet occurred when IC spoke to the Wounaan in Buenaventura, however, one person concluded that “Indigenous people face an emergency situation throughout the country, not just in the Rio San Juan.”

The Wounaan are now changing their strategy over how to return to their territory, turning away from the municipal and departmental authorities and towards the Ministry of the Interior, the Ombudsman, and the international community.

The municipal authorities are not cooperating with the indigenous people; they always tell lies – they always say they will do something ‘mañana.’ We present our willingness to return but we need guarantees of security and dignity in our territory. Because the local level has not achieved anything we go to the national and international level, including to NGOs and the UN.

The UNHCR’s Wellington Carneiro cautions that the government ministries in Bogota lack a presence in the region and don’t have “a clear picture on the problems of the Wounaan,” however, “there is also a very negative stigmatization of the indigenous communities by the local authorities.”

Photo: Robin Llewellyn

One of the Wounaan observed that local officials “always come and talk, and then afterwards [do] nothing.” She said that her emphasis was on maintaining and developing the cultural and political activities of the group: “We need to strengthen our community so we can defend our territory”.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 4, 2014 | Colonialism & Conquest, Property & Material Destruction

By Andrew Wight & Taran Volckhausen / Colombia Reports

Colombia’s second largest rebel group the ELN detonated explosives Wednesday at four crude oil holding pools along the Caño Limon – Coveñas pipeline in the state of North Santander.

A large blaze caused by the attacks created panic in the local population, who were forced to flee their homes, according to local media reports.

Authorities were taking measures to prevent further environmental damage after the attacks as well as reconstruct the damaged holding pools.

The attack marks the first attack by the ELN in 2014, although the rebel group has been coordinating attacks on Colombia’s oil production infrastructure for the past few months, declaring war against multinational oil companies operating in the country in November.

In a statement released on the ELN website Tuesday, Colombia’s second largest guerrilla group declared war on the multinationals and oil companies “plundering” the country’s natural resources.

The ELN’s Eastern War Front Commander, Manuel Vasquez Castaño, confirmed that a slew of recent attacks directed at Colombia’s oil infrastructure have been intended to hurt the pockets of multinationals active in the country.

Once again, we reaffirm our belligerent stance to confront multinationals and their repressive apparatus: the plunderers and exploiters of natural resources,” he said. “Colombia is a colony of North American imperialism — bourgeois elites in power sold to the highest bidder and in the name of democracy deliver natural resources to their Yankee masters.

The statement went on to discuss the high prices of Colombia’s internal combustible market, which lead to nationwide strikes in the trucking sector this past summer and have been sited by farm organizers involved in ongoing negotiations with the government as a reason for the financial insolubility of the agricultural market.

“We are one of the top oil-producing countries worldwide,” said Vasquez, “but Colombia has (some of) the world’s most expensive gasoline.”

The rebel group has asked for broad talks along the lines of the peace deal currently being negotiated in Havana, Cuba between government officials and the FARC, Colombia’s largest rebel group.

But despite agreeing to initiate the process, the Colombian government has yet to reach out to the ELN central command, which has repeatedly called for the start of discussions, and recently launched an offensive against oil and gas pipelines in rural Colombia, in what is believed to be a measure to pressure the Colombian government into talks.

Despite the ELN’s efforts, Colombia’s state-owned Ecopetrol oil company reported a net profit of $2.05 billion in the third quarter of 2013 and record levels of oil production.

The Colombian government has yet to respond to the ELN’s most recent announcement, and hasn’t indicated that any plan to develop talks will be forthcoming.

The ELN, which continues to employ the anti-capitalist rhetoric of its origins as a Catholic-Marxist revolutionary group, has since become dependent on the illicit mining and gold trade, running operations throughout the country that exploit Colombia’s rural poor and generate sizable revenue streams for the group’s other activities.

From Systemic Capital

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 10, 2013 | Defensive Violence, Indigenous Autonomy, Mining & Drilling

By Jorge Barrera / APTN

A Colombia guerilla group is trying to draw Ottawa into its battle with a Toronto-based mining company which is quietly trying to secure the release of one of its executives who has been held hostage since January.

The Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional (ELN) kidnapped Gernot Wober, 47, on Jan. 18, during an attack on the Snow Mine camp in Bolivar state, which sits in the northern part of the country. The guerilla group kidnapped five other people, including three Colombians and two Peruvians, who have all since been released.

The guerilla group says that Wober, the vice-president of Toronto-based Braeval Mining Corp, won’t be released until the company gives up gold mining concessions in the San Lucas mountain range which the ELN claims were initially given to local miners who live in the area.

In a statement issued Wednesday and posted on the guerilla group’s website, the ELN took aim at the Canadian government.

“The Canadian government should at least be concerned about whether its anti-corruption laws are being followed by Canadian companies in their foreign operations,” said the ELN. “Neither the Colombian nor Canadian governments have bothered to investigate our accusations about the dispossession of four mining concessions held by communities in the southern part of Boliver (state) by the Northern American company Braeval Mining Corporation.”

The ELN claimed the Colombian government was increasing military operations against the group to secure Wober’s release.

The ELN is the smaller of Colombia’s main guerilla groups. It’s estimated the ELN has between 2,000 to 3,000 guerilla fighters.

A spokesperson for Braeval said the company has been advised not to comment on the kidnapping.

Foreign Affairs emailed a statement to APTN National News saying federal government “officials continue to work closely with our partners on the ground.” The statement said officials are also in contact with Wober’s family.

“The government of Canada will not comment on efforts to secure the hostage’s release,” said the statement. “Due to privacy considerations, we cannot provide additional information about the situation.”

The ELN has released no evidence to back its claims that Braeval wrongly obtained the mining concessions.

According to his on-line work history, Wober has extensive experience in the mining sector, including involvement in projects in the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, British Columbia and Manitoba.

The activities of foreign mining companies, including those based in Canada, have long been a point of contention among Indigenous and local communities in Colombia.

Under Canada’s free trade agreement with Colombia, Ottawa is required to present an annual report on human rights in Colombia every year. Last year’s report failed to report on human rights in the country.

The National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (NIOC) has called on Canada to pressure the Colombian government to respect Indigenous rights in its mining laws.

In a recent interview with Maria Patricia Tobon Yagari, a lawyer with the NIOC said that mining companies present a bigger threat than the armed groups because the firms fuel the violence.

“The presence of these miners have reinforced (the violence) because they have benefited from it. By using private security they have forced these Indigenous groups and Colombian campesinos to resist and it has increased the violence in the territories,” said Tobon Yagari.

Tobon Yagari was scheduled to appear on Parliament Hill on May 22 but her visa was initially denied by Ottawa.

Tobon Yagari said foreign mining firms have put pressure on the Colombian government to pass mining laws tailored in the interest of development.

“Of course Canadian miners have a large interest in getting legislation in their favour,” she said. “That is what is happening without our mining code and our situation in Colombia.”

Many Indigenous communities in Colombia are clinging precariously on the edge of extinction.

Of the 102 documented Indigenous nations in Colombia, 32 have populations under 500, 18 have populations of 200, while 10 have less than 100.

Tens of thousands of Indigenous people have been displaced from their territories which are often rich in minerals and hydrocarbons eyed by foreign mining firms.

Amnesty International has said it’s concerned about deepening ties between Canada and Colombia’s military as a result of the free trade deal.

“And recent changes to export controls in Canada to allow for the sale of automatic firearms to Colombia,” have added to list of problematic issues, said the international human rights organization.

The situation of Indigenous peoples in Colombia is so dire that the UN Special Rapporteur on Indigenous Peoples James Anaya has called for the UN special advisor on genocide to visit Colombia.

From APTN