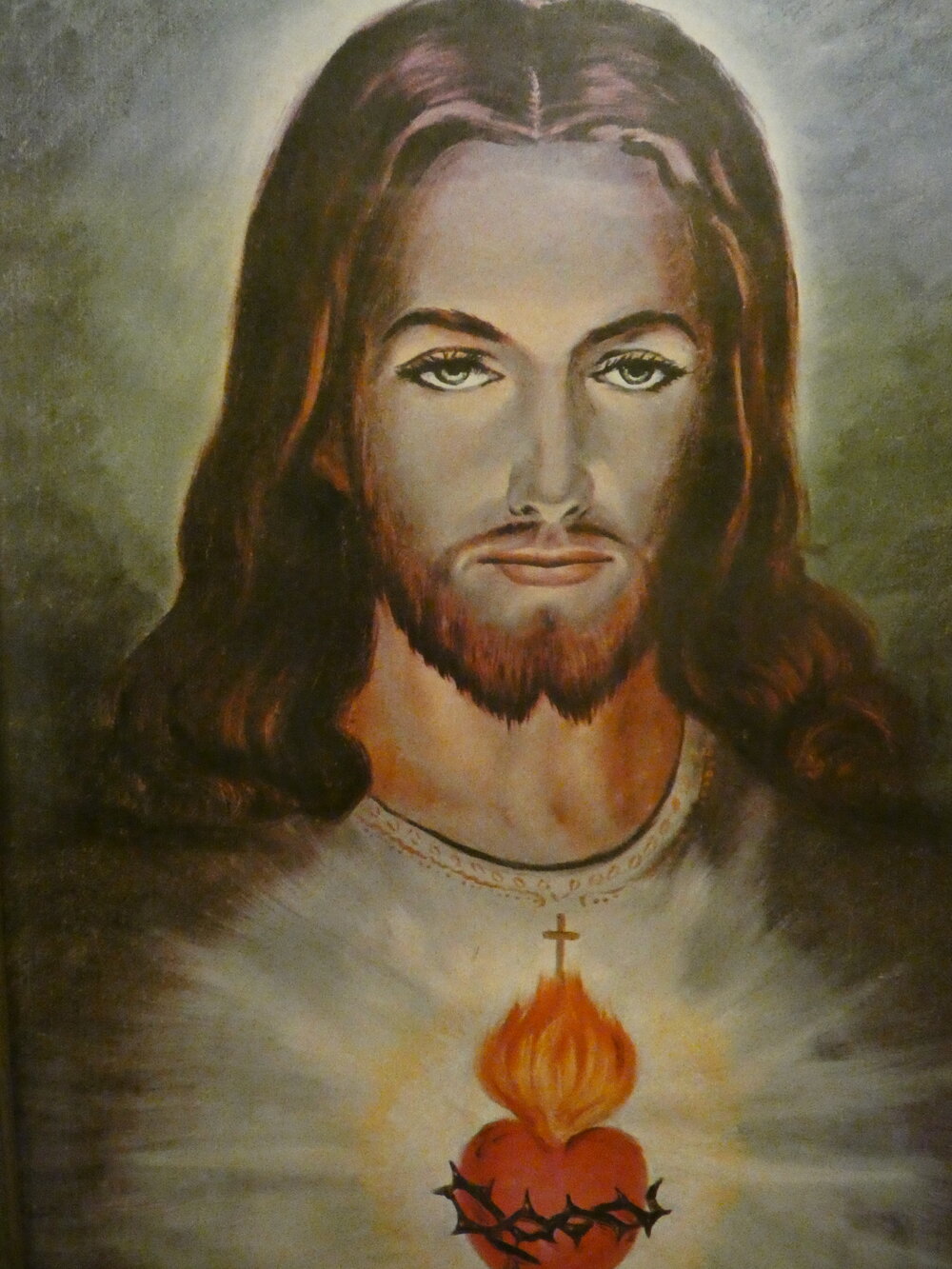

The Ohio River is the most polluted river in the United States. In this series of essays entitled ‘The Ohio River Speaks,‘ Will Falk travels the length of the river and tells her story. Find the rest of Will’s journey with the Ohio River here. Featured image: White Jesus photographed in the home of the author’s grandparents.

by Will Falk

In my grandparents’ house in Owensboro, KY, the Ohio River spoke to me through Jesus.

After the incident with my grandfather in the hospital parking lot, I returned to my grandparents’ home with my mother and grandmother. One step through the front door and I counted no less than six Jesuses staring at me from the wall. Three different crucifixes hung over three different doorways. Dozens of prayer cards and placards my grandmother couldn’t bring herself to get rid of littered table tops and shelves. And, a statue of a blonde, blue-eyed infant Jesus, dressed as a Renaissance princeling, stood guard over the centerpiece of my grandmother’s cluttered little living room: a massive Bible.

These images of Catholic Christianity filled me with a mixture of painful emotions. The depictions of Jesus as white annoyed me with their historical inaccuracy. The prayer cards invoked my wish that more people would spend more time acting to change the real world than praying. The crucifixes, with their classically Catholic goriness, displayed the broken and bloodied body of a man I had been taught was tortured and killed for my personal sins. Shame rushed in until I remembered that the Roman soldiers who murdered Jesus of Nazareth 2000 years ago could not have cared less if I missed Sunday Mass, cussed, or even used a condom while having premarital sex. But, by then, an old, but familiar anger burned within me.

I was angry about how, as a child, adults sought to control my behavior by threatening me with the eternal suffering of hell. I was angry about the guilt Catholic teachings encouraged me to feel when my behavior conflicted with arbitrary Church doctrine. I was angry about the long history of atrocities Christians have inflicted. I was angry about the Crusades, the Inquisition, the Doctrine of Discovery, and the witch hunts. I was angry about the sexual abuse so many priests have perpetrated on so many children.

I felt sorrow, too. I felt sorrow for my great uncle, a priest in his 80s, who told my mother and me about some resentment he felt over the way that his parents took him to the seminary at 13. In other words, my great-grandparents determined their son would take the vow of celibacy required of Catholic priests before their son had even finished puberty.

I felt sorrow for both of my grandmothers who, encouraged by the Catholic Church, stayed nearly permanently pregnant during the prime of their lives. My paternal grandmother gave birth to eight children. And, my maternal grandmother – the one whose house I was currently in – gave birth to seven children. To illustrate this more vividly, my maternal grandmother (93 years old and with slight dementia) recently asked me: “You know how women get periods, Will?” I, wondering where this was going, cautiously answered, “Yes, Granny, I do.” My grandmother then said, “Well, can you believe it? From the time I was pregnant with Clare until after Cecilia was born, I only had one period!” My grandmother burst out laughing, but I almost started crying.

It is funny, of course, but the more I thought about it, the sadder I got. My aunt Clare is my mom’s oldest sibling and my aunt Cecilia is her youngest, so my grandmother became pregnant and gave birth to 7 children – and only experienced one period during that entire time. As a man, I can only imagine what being pregnant and nursing for that long must have felt like. To make matters worse, each time either one of my grandmothers became pregnant, she had one more child to take care of than the time before.

Just a few hours after I had committed to learning how to treat my grandparents more compassionately, confronting the icons and imagery of Catholicism in my grandparents’ home already caused me to question this commitment. I wanted to blame my grandparents for forcing Catholicism on their children. I wanted to blame my parents for attempting to do the same to my sister and me. I wanted to direct my anger for the pain Catholicism has caused me at my grandparents and parents – people within reach. In order to honor my commitment, however, I knew I had to move past blaming my family and had learn to understand. The question was: How?

A prayer card from my grandmother’s collection.

***

Before I could begin to answer this question, I had to justify spending precious time and invaluable energy trying to understand my family’s spirituality while I was supposed to be writing about the needs of the Ohio River. Achieving this understanding would primarily be an internal process, a journey through my memories and emotions, through history books and conversations with my relatives. At a time when more industrial poisons and more agricultural pollution were pumped into the Ohio River with every passing day, could the Ohio River forgive me for taking this personal journey?

Intellectually, the answer seemed obviously no. Instinctually, however, I felt something urging me to begin this journey. I did not yet understand why, but my intuition insisted that this journey would yield answers to this project’s two central questions: Who is the Ohio River? And, what does she need?

There was something deeper contributing to my hesitation: I was afraid of my family’s reaction if I criticized the Catholic Church and their participation in it. If I was not careful, my criticisms might come off as nothing more than immature contrarianism. I could not sugar coat the pain the Catholic Church has caused me or gloss over the history of Church-sponsored genocides, but it would be disingenuous to lay most of that pain at the feet of my family. Their Catholic beliefs were rooted in generations of indoctrination, passed down by well-meaning mothers and fathers. My family’s participation in Catholicism followed a long history involving the destruction, erasure, and cooptation of the traditional cultures of Europe. A true understanding of why my family has practiced, and still practices, Catholicism would have to attend to 2000 years of history.

I faltered under the weight of it all – the battle between my intellect and my instinct, the fear of my family’s reaction, and the enormity of the history of the Catholic Church. For days, I flip-flopped between ignoring my family’s Catholic beliefs and embracing my intuition that there were useful lessons for both the Ohio River and me if I was just brave enough to delve into that history.

***

I retreated to the little cabin the Troutmans had been letting me use in Potter County, PA. With very little writing to show for my confrontation with my Catholic upbringing, I had just about convinced myself to ignore my family history and head down to Pittsburgh to write about how that city has affected the Ohio River when Melissa Troutman invited me to come with her to run a few errands in Olean, NY. (She probably noticed the squirrelly look that had grown over me while I debated my family’s spirituality during my self-imposed isolation and figured I could use some time outside of my own head.)

Olean sits on the river the indigenous Seneca call Ohi:yo’. To the Seneca, the Allegheny and the Ohio Rivers are one and the same. And, as I’ve explained in earlier installments of this project, I follow the Seneca’s lead. Melissa needed to get her oil changed. So, we dropped her car off and took her terrier Runo for a walk in Olean’s Franchot Park, on the banks of Ohi:yo’.

The river is not visible from most of the park because of a massive earthen flood control mound. Runo, proving the wisdom of his species, took off over the mound, forcing Melissa and I to follow. I crested the mound to find the Ohio River flowing from east to west below me, curling through the curves formed by the hills’ shoulders. Despite knowing I would find the Ohio River, I was stunned once again by the realization that no matter how much time I spend thinking about her, there is no substitute for being in her presence. And, I found the clarity that had eluded me while I had contained my search to the round confines of my own skull miles from the main stem of the Ohio River.

The Ohio River turned the gray, October sky into silver. She glittered under the russet leaves of autumnal oaks, the golden bursts of aspens, and the brash crimsons of changing maples. Emerald feathers flashed where mallards, reminded by the chill breeze of the need for winter fat, tipped their tail feathers up and fed on underwater plants and insects. Honking Canada geese carried, once again, the voices of my ancestors.

Ask the river what to do.

So, I did. Out loud. A few moments later a single seagull caught my attention, descending from the clouds. She took her time, making slow, wide circles above the water. On that overcast day, all the colors of the sky – the spectrum of whites and grays – settled in her feathers. When she reached my eye-level, she made three or four circles without making progress towards the river’s surface. I got the impression she wanted me to notice her. The gentle repetitions in her circular flight-paths hypnotized me. Memories flooded through me. This was not the first time a seagull had carried me a message.

***

It’s the fourth day after I tried to kill myself the first time. The St. Francis psyche ward is on the seventh floor of an eight-floor building. For exercise and because there’s nothing else to do, I brave the fluorescent lights outside my room and pace the long hallway that connects most of the seventh floor.

At each end of the hallway are wide windows. One looks west into the rows of old company housing for the Milwaukee Iron Company. The other looks east over the waters of Lake Michigan. Patients are not allowed off the seventh floor and there are rusty bars outside the glass in case we were tempted to take that route to fresh air. I try to open a window facing Lake Michigan anyway. It will not open. A heavy snow begins to fall surrounding the hospital in more white. I press my forehead against the cold glass pane. The cold feels good.

It is not long before I see an old spotted seagull awkwardly wheeling and diving through the falling snow. I am mesmerized by the odd gracefulness in his seemingly drunken turns through the snow. His circles bring him closer and closer to my window. I wonder why he is flying through such treacherous conditions. He is the only bird in the sky. As he flies closer, I am stricken with the beauty of his grayness against the white.

I begin to believe the drunk old gull is braving the snowstorm to speak to me. When he lands on the sill of the window I’m watching from, I know he is. He pauses on the window sill, makes eye contact with me, dips a wing, leaps, and wobbles back toward Lake Michigan. The waves on the lake ripple gray, too. The wet snow falls slowly, gingerly over the waters. They hesitate, hanging a moment in the air, before they are swallowed by the lake. White becomes gray. I drink up the colors following one gray wave after another from their birthplace on the horizon until they wash not far below me onto the shore.

While still in the hospital, I begin trying to write about how the seagull showed me color again. I do not know why. I just feel I should. It is instinctual. There is no articulable rationality that I can come up with. Writing about the seagull is like choosing a path when you are utterly lost. I see a path and go.

While trying to dress the memory in words, the experience cements in my mind. A place – neither completely concrete nor completely abstract, neither completely within me nor completely without me – begins to form. My heart and my memory meet my paper and my pen and the gull’s spotted gray wings flap on. He navigates spiritual planes, physical spaces, the long distances of memory, and fat snowflakes to lead me out over Lake Michigan.

My contemplation intensifies.

While I seek the right words, find them inadequate, scratch them out, and write new ones, the meaning of the gull’s visit grows. Color bleeds from the tip of my pen and begins to trickle to the edges of my memory. Though I cannot make out their tunes, faint songs reach my ears from far away. Voices in strange languages enchant me. I feel hair stir on my head, a twitch in my leg, water collecting on my tongue. I feel small sensations after a long numbness. My memory begins to stretch. The blood returns. It feels good.

The beginnings of a new understanding are planted within me. I sense mystery. I sense possibility. My world was pain, anguish, and the certainty of more pain and anguish. Now, whispers kiss my brow speaking rumors of something new.

***

Runo dropped a stick, his favorite kind of toy, on my feet. The seagull splashed down next to the mallards and geese. And, I came back to the present.

Seven years after the old grey gull led me to writing in the mental hospital, I knew the Ohio River seagull was urging me to write, too. But, was I supposed to write about my family history and Catholicism? I stood watching the river for a few more minutes and no answer seemed apparent. I turned to catch up with Melissa and Runo. And the first thing I saw was two towering church steeples: The Roman Catholic Basilica of St. Mary of the Angels.

![[The Ohio River Speaks] The Veil Of Unreality](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2020/11/OnthebanksoftheWabash.jpg)