From a “critique” of my work on the latest Professor Watchlist, I learned that I’m a threat to my students for contending that we won’t end men’s violence against women “if we do not address the toxic notions about masculinity in patriarchy … rooted in control, conquest, aggression.”

That quote is the “evidence” that I am one of those college professors “who discriminate against conservative students, promote anti-American values, and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom,” according to the watchlist’s mission statement.

This rather thin accusation appears to flow from my published work instead of an evaluation of my teaching, which confuses a teacher’s role in public with the classroom. So, I’ll help out the watchlist and describe how I address these issues at the University of Texas at Austin, where I’m finishing my 25th year of teaching. Readers can judge the threat level for themselves.

I just completed a unit on the feminist critique of the contemporary pornography industry in my course “Freedom: Philosophy, History, Law.” We began the semester with On Liberty by John Stuart Mill (I’ll assume the Professor Watchlist approves of that classic book), examining how various philosophers have conceptualized freedom. We then studied how the term has been defined and deployed politically throughout U.S. history, ending with questions about how living in a society saturated with sexually explicit material affects our understanding of freedom. I provided context about feminist intellectual and political projects of the past half-century, including the feminist critique of men’s violence and of mass media’s role in the sexual abuse and exploitation of women in a society based on institutionalized male dominance (that is, patriarchy).

The revelations about Donald Trump’s sexual behavior during the campaign provided a “teachable moment” that I didn’t think should be ignored. I began that particular lecture, a week after the election, by emphasizing that my job was not to tell students how to act in the world but to help them understand the world in which they make choices.

Toward that goal, I pointed out that we have a president-elect who has bragged about being sexually aggressive and treating women like sexual objects, and that several women have testified about behavior that—depending on one’s evaluation of the evidence—could constitute sexual assault. Does is seem fair, I asked the class, to describe him as a sexual predator? No one disagreed.

Trump sometimes responded by contending that Bill Clinton was even worse. Citing someone else’s bad behavior to avoid accountability is a weak defense (most people learn that as children), and of course Trump wasn’t running against Bill, but we can learn from examining the claim.

As president, Bill Clinton abused his authority by having sex with a younger woman who was first an intern and then a junior employee. He settled a sexual harassment lawsuit out of court, and he has been accused of rape. Does it seem fair to describe Bill Clinton as a sexual predator? No one disagreed.

So, we live in a world in which a former president, a Democrat, has been a sexual predator, yet he continues to be treated as a respected statesman and philanthropist. Our next president, a Republican, was elected with the nearly universal understanding that he has been a sexual predator. How can we make sense of this? A feminist critique of toxic conceptions of masculinity and men’s sexual exploitation of women in patriarchy seems like a good place to start.

In that class, I spent considerable time reminding students that I didn’t expect them all to come to the same conclusions but that they all should consider relevant arguments in forming judgments. I repeated often my favorite phrase in teaching: “Reasonable people can disagree.” Student reactions to this unit of the class varied, but no one suggested that the feminist critique offered nothing of value in understanding our society.

Is presenting a feminist framework to analyze a violent and pornographic culture politicizing the classroom, as the watchlist implies? If that’s the case, then the decision not to present a feminist framework also politicizes the classroom, in a different direction. The question isn’t whether professors will make such choices—that’s inevitable, given the nature of university teaching—but how we defend our intellectual work (with evidence and reasoned argument, I hope) and how we present the material to students (encouraging critical reflection).

If the folks who compiled the watchlist had presented any evidence that I was teaching irresponsibly, I would take the challenge seriously. At least in my case, the watchlist didn’t. But rather than assign a failing grade, I’ll be charitable and give the project an incomplete, with an opportunity to turn in better work in the future.

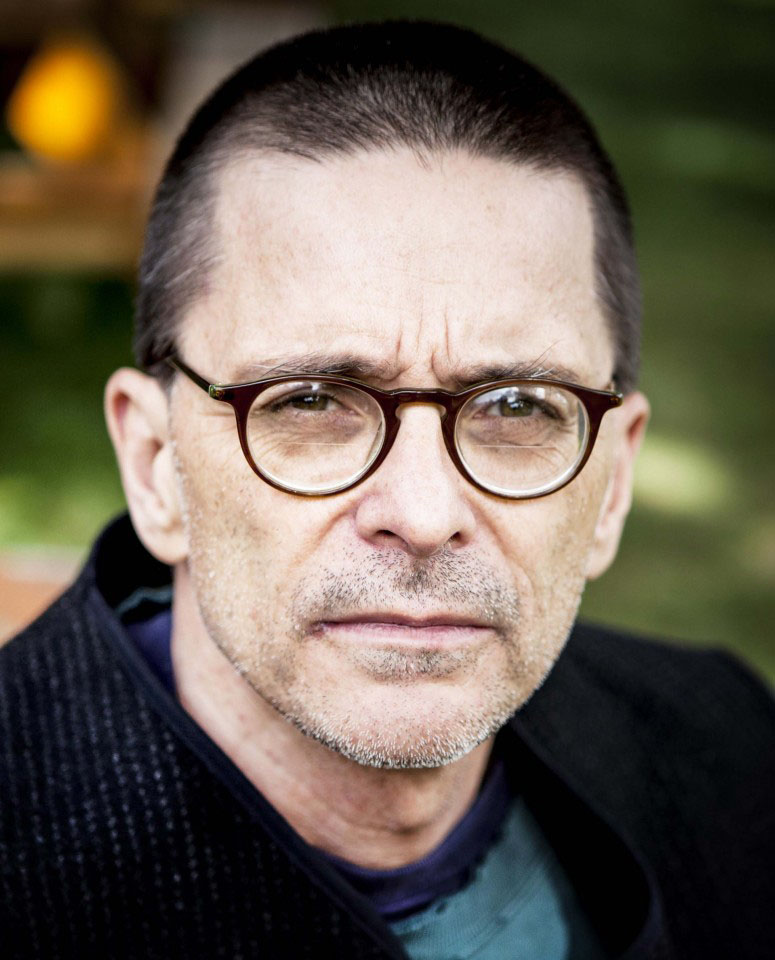

Robert Jensen is a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Texas at Austin, and author of The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men, to be published in January by Spinifex Press. Other articles are online at http://robertwjensen.org/. He can be reached at rjensen@austin.utexas.edu.

heh that watchlist sounds ridiculous.

Sad to hear its happening though.

That there are people out there that are so eager to try and shut down dialogue.

I find this site and mission statement abhorrent. I could talk about many things it offends, but I’ll start and end with academic freedom, a principle that trumps Trump