In 1993 Michael Carter was arrested and indicted for underground environmental activism. Since then he’s worked aboveground, fighting timber sales and oil and gas leasing, protecting endangered species, and more. Today, he’s a member of Deep Green Resistance Colorado Plateau, and author of the memoir Kingfishers’ Song: Memories Against Civilization.

Time is Short spoke with him about his actions, underground resistance, and the prospects and problems facing the environmental movement. The first part of this interview is available here, and the third part here.

Time is Short: Your actions weren’t linked to other issues or framed in a greater perspective. How important do you think having well-framed analysis is in regards to sabotage and other such actions?

Michael Carter: It is the most important thing. Issue framing is one of the ways that dissent gets defeated, as with abortion rights, where the issue is framed as murder versus convenience. Hunger is framed as a technical difficulty—how to get food to poor people—not as an inevitable consequence of agriculture and capitalism. Media consumers want tight little packages like that.

In the early ‘90s, wilderness and biodiversity preservation were framed as aesthetic issues, or as user-group and special interests conflict; between fishermen and loggers, say, or backpackers and ORVers. That’s how policy decisions and compromises were justified, especially legislatively. My biggest aboveground campaign of that time was against a Montana wilderness bill, because of the “release language” that allowed industrial development of roadless federal lands. Yet most of the public debate revolved around an oversimplified comparison of protected versus non-protected acreage numbers. It appeared reasonable—moderate—because the issue was trivialized from the start.

That sort of situation persists to this day, where compromises between industry, government, and corporate environmentalists are based on political framing rather than biological or physical reality—an area that industry or motorized recreationists would agree to protect might have no capacity for sustaining a threatened species, however reasonable the acreage numbers might look. Activists feel obliged to argue in a human-centered context—that the natural world is our possession, whether for amusement or industry—which is a weak psychological and political position to be in, especially for underground fighters.

When I was one of them, I never felt I had a clear stance to work from. Was I risking a decade in prison for a backpacking trail? No. Well then what was I risking it for? I chose not to think that deeply, just to rampage onward. That was my next worst mistake after bad security. Without clear intentions and a solid understanding of the situation, actions can become uncoordinated, and potentially meaningless. No conscientious aboveground movement will support them. You can get entangled in your own uncertainty.

If I were now considering underground action—and of course I’m not, you must choose to be aboveground or underground and stick with it, another mistake I made—I would view it as part of a struggle against a larger power structure, against civilization as a whole. It’s important to understand that this is not the same thing as humanity.

TS: You called civilization a plan based on agriculture. Could you expand on that?

MC: Nothing else that the dominant culture does, industrial forestry and fishing, generating electricity, extracting fossil fuels, is as destructive as agriculture. None of it’s possible without agriculture. There’s some forty years of topsoil left, and agriculture is burning through it as if it will last forever, and it can’t. Topsoil is the sand in civilization’s hourglass, the same as fossil fuels and mineral ores; there is only so much of it. When it comes to physical limits, civilization has no rationality, or even a sense of its own ultimate self-interest; only a hidden-in-plain-sight secret that it’s going to consume everything. In a finite world it can never function for long, and all it’s doing now is grinding through the last frontiers. If civilization is still continuing twenty years from now, it won’t matter how many wilderness areas are designated; civilization is going to consume those wilderness areas.

TS: How is that analysis helpful? If civilization can never be sustained, doesn’t that remove any hope of success?

MC: If we’re serious about protecting life and promoting justice, we have to acknowledge that civilized humanity will never voluntarily take the steps needed for a sustainable way of life, because its history is entirely about war and occupation. That’s what civilization does: wage war and occupy land. It appears as though this is progress, that it’s humanity itself, but it’s not. Civilization will always make power and dominance its priority, and will never allow its priority to be challenged.

For example, production of food could be fairly easily converted from annual grains to perennial grasses, producing milk, eggs, and meat. Polyface Farms in Virginia has demonstrated how eminently possible this is; on a large scale that would do enormous good, sequestering carbon and lowering diabetes, obesity, and pesticide and fertilizer use. But grass can’t be turned into a commodity; it can’t be stored and traded, so it can never serve capitalism’s needs. So that debate will never come up on CNN, because it falls so far outside the issue framing. Hardly anyone is discussing what’s really wrong, only which capitalist or nation state will get to the last remaining resources first and how technology might cope with the resulting crises.

Another example is the proposed copper mine at Oak Flat, near Superior, Arizona. The Eisenhower administration made the land off-limits to mining in 1955, and in December 2014 the US Senate reversed that with a rider to a defense authorization bill, and Obama signed it. Arizona Senator John McCain said, “To maintain the strength of the most technologically-advanced military in the world, America’s armed forces need stable supplies of copper for their equipment, ammunition, and electronics.” See how he justifies mining copper with military need? He’s closed the discussion with an unassailable warrant, since no one in power—and hardly anyone in the public at large—is going to question the military’s needs.

TS: Are you saying there’s no chance of voluntary reform?

MC: I’m saying that it’s going to be a fight. Significant social change is usually involuntary, contrary to popular notions about “being the change you want to see in the world” and “majority rules.” Most southern whites didn’t want the US Civil Rights Movement to exist, much less succeed. In the United States democracy is mostly a fictional theory anyway, because a tiny financial and political elite run the show.

For example, in the somewhat progressive state of Oregon, the agriculture lobby successfully defeated a measure to label foods containing genetically modified organisms. A majority of voters agreed they shouldn’t know what’s in their food, their most intimate need, because those in power had enough money to convince them. There’s little hope in trying to reason with the people who run civilization, or who are otherwise trapped by it, politically or financially or however. So long as the ruling class is able to extract wealth from the land and our labor, they will. If they’ve got the machinery and fuel to run their economy, they will eventually find the political bypasses to make it happen. It will consume lives and land until there’s nothing left to consume. When the soil is gone, that’s essentially it for the human species.

What’s the point of compromising with a political system that’s patently insane? A more sensible way of approaching the planet’s predicament would be to base tactical decisions on a strategy to strip power from those who are destroying the planet. This is the root, what we have to mean when we call it a radical—root-focused—struggle.

Picture a world with no food, rising temperatures, disease epidemics, drought, war. We see it unfolding now. This is what we’re fighting against. Or rather we’re fighting for a world that can live, a world of forests and prairies and free flowing rivers that build and stabilize soil and sustain biological diversity and abundance. Our love of the world must be what guides us.

TS: You’re suggesting a struggle that completely changes how humans have arranged themselves, the end of the capitalist economy, the eventual collapse of the nation-state model of society. That sounds impossibly difficult. How might resisters approach that?

MC: We can begin by building a movement that functions as a cultural replacement for the culture we’re stuck in now. Since civilized culture isn’t going to support anyone trying to take it apart, we need other systems of material, psychological, and emotional support.

This would be particularly important for an underground movement. Ideally they would have a community that knows their secrets and works alongside them, just as militaries do. Building that network will be difficult to do in secret, because if they’re observing tight security, how do they even find others who agree with them? But because there’s little one or two people can do by themselves, they’ll have to find ways to do it. That’s a problem of logistics, however, and it’s important to separate it from personal issues.

When I was doing illegal actions, I wanted people to notice me as a hardcore environmentalist, which under the circumstances was foolish and narcissistic to the point of madness. If you have issues like that—and lots of people do, in our bizarre and hurtful culture—you need to resolve them with self-reflection and therapy, not activism. The most elegant solution would be for your secret community to support and acknowledge you, to help you find the strength and solidarity you need to do hard and necessary work, but there are substitutes available all the same.

TS: You’ve been involved with aboveground environmental work in the years since your underground actions. What have you worked on, and what are you doing now?

MC: I first got involved with forestry issues—writing timber sale appeals and that sort of thing. Later I helped write petitions to protect species under the Endangered Species Act. I burned out on that, though, and it took me a long time to get drawn back in. Aboveground people need the support of a community, too—more than ever. Derrick Jensen’s book A Language Older Than Words clarified the global situation for me, answered many questions I had about why things are so difficult right now. It taught me to be aware that as civilized culture approaches its end, people are getting ever more self-absorbed, apathetic, and cruel. Those who are still able to feel need to stand by each other as well as they can.

When Deep Green Resistance came into being, it was a perfect fit, and I’ve been focused on helping build that movement. Susan Hyatt and I are doing an essay series on the psychology of civilization, and how to cultivate the mental health needed for resistance. I’m also interested in positive underground propaganda. Having stories to support what people are doing and thinking is important. It helps cultivate the confidence and courage that activists need. That’s why governments publish propaganda in wartime; it works.

TS: So you think propaganda can be helpful?

MC: Yes, I do. The word has a negative connotation for some good reasons, but I don’t think that attempting to influence thoughts and actions with media is necessarily bad, so long as it’s honest. Nazi Germany used propaganda, but so did George Orwell and John Steinbeck. If civilization is brought down—that is, if the systems responsible for social injustice and planetary destruction are permanently disabled—it will require a sustained effort for many years by people who choose to act against most everything they’ve been taught to believe, and a willingness to risk their freedom and lives to bring it about. Entirely new resistance cultures will be needed. They will require a lot of new stories to sustain a vision of who humans really are, and what our lives are for, how they relate to other living things. So far as I know there’s little in the way of writing, movies, any sort of media that attempts to do that.

Edward Abbey wrote some fun books, and they were all we had; so we went along hoping we’d have some of that fun and that everything might come out all right in the end. We no longer have that luxury for self-indulgence. I’m not saying humor doesn’t have its place—quite the opposite—but the situation of the planet and social situation of civilization is now far more dire than it was during Abbey’s time. Effective propaganda should reflect that—it should honestly appraise the circumstances and realistically compose a response, so would-be resisters can choose what their role is going to be.

This is important for everyone, but especially important for an underground. In World War II, the Allies distributed Steinbeck’s propaganda novel The Moon is Down throughout occupied Europe. It was a short, simple book about how a small town in Norway fought against the Nazis. It was so mild in tone that Steinbeck was accused by some in the US government of sympathizing with the enemy for his realistic portrayal of German soldiers as mere people in an awful situation, and not superhuman monsters. Yet the occupying forces would shoot anyone on the spot if they caught them with a copy of the book. Compare that to Abbey’s books, and you see how far short The Monkey Wrench Gang falls of the necessary task.

TS: Can you suggest any contemporary propaganda?

Derrick Jensen’s Endgame books are the best I can think of, and the book Deep Green Resistance. There’s some negative-example propaganda worth mentioning, too. The book A Friend of the Earth, by T.C. Boyle. The movies “The East” and “Night Moves” are both about underground activists, and they’re terrible movies, at least as propaganda for effective resistance. “The East” is about a private security firm that infiltrates a cell whose only goals are theater and revenge, and “Night Moves” is even worse, about two swaggering men and one unprepared woman who blow up a hydroelectric dam.

The message is, “Don’t mess with this stuff, or you’ll end up dead.” But these films do point out some common problems of groups with an anarchistic mindset: they tend to belittle women and they operate without a coherent strategy. They’re in it for the identity, for the adrenaline, for the hook-up prospects—all terrible reasons to engage. So I suppose they’re worth a look for how not to behave. So is the documentary film “If a Tree Falls,” about the Earth Liberation Front.

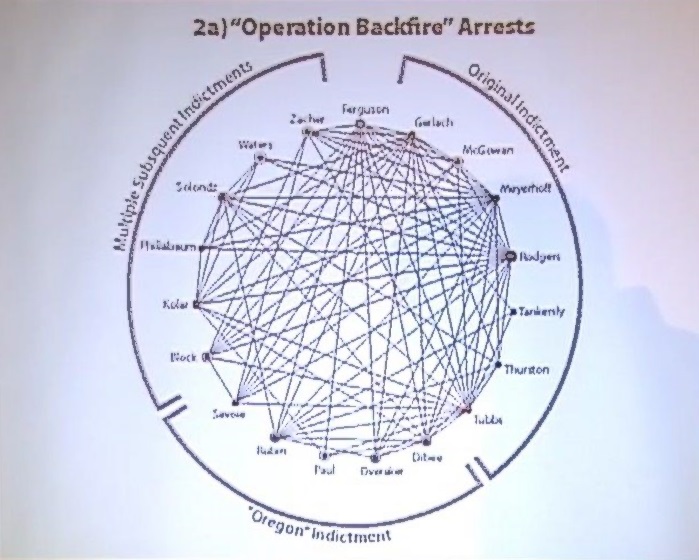

“Operation Backfire” Arrests. Links between defendants illustrate lax security practices, making them far more vulnerable. From Deep Green Resistance – Organizational Structures for Resistance Part 4 of 4

Social change movements can suffer from problems of immaturity and self-infatuation just like individuals can. Radical environmentalism, like so many leftist causes, is rife with it. Most of the Earth First!ers I knew back in the ‘90s were so proud of their partying prowess, you couldn’t spend any time with them without their getting wasted and droning on about it all the next day. One of the reasons I drifted away from that movement was it was so full of arrogant and judgmental people, who seemed to spend most of their time criticizing their colleagues for impure living because they use paper towels or drive an old pickup instead of a bicycle.

This can lead to ridiculous guilt-tripping pissing matches. It’s no wonder environmentalists have such a bad reputation among the working class, when they’re indulging in self-righteous nitpicking that’s really just a reflection of their own circumstantial advantages and lack of focus on effectively defending the land. Tell a working mother to mothball her dishwasher because you heard it’s inefficient, see how far you get. It’s one of the worst things you can say to anyone, especially because it reinforces the collective-burden notion of responsibility for environmental destruction. This is what those in power want us to think. Developers build new golf courses in the desert, and we pretend we’re making a difference by dry-brushing our teeth. Who cares who’s greener than thou? The world is being gutted in front of our eyes.

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org

Trackbacks/Pingbacks