by DGR News Service | May 27, 2022 | ACTION, Direct Action, Property & Material Destruction

Editor’s note: In these dire times, we are glad to see increasing adoption of and advocacy for eco-sabotage. However, when it comes to tactics and strategy, context matters. No tactic can be judged as “effective” or “ineffective” in isolation. Goals, assumptions, and political circumstances must be considered before selecting methods.

In the political context of 2022 Britain, the actions of the eco-sabotage group “Tyre Extinguishers” may be amplifying political pressure to reduce carbon pollution and curtail the hegemony of the automobile and building a cultural acceptance for more drastic illegal actions on behalf of the planet. This type of small-scale act of minor eco-sabotage may also be useful for training and propaganda. This is the best case outcome.

A more pessimistic view is that these actions could lead to an upper-class backlash, further empower surveillance and repression against environmentalists, and put activists at risk within the legal system. However, we largely discount this interpretation, as the upper classes are already hostile to environmental action, this type of illegal action would likely lead to minimal punishments if prosecutions did take place, and police in Britain are already harassing, infiltrating, and disrupting environmental movements.

A more valid critique—made in the spirit of solidarity—is that these actions are hitting the wrong targets and are inadequate to address the crisis we are facing. Halting global warming and reversing ecological decline will likely require massive, coordinated eco-sabotage against industrial infrastructure—not just individual cars. In that sense, these actions may represent a failure of target selection when compared to the Valve Turners or the DAPL eco-saboteurs.

The Tyre Extinguishers chose their targets based on the idea that pressure on governments can halt the climate crisis and the destruction of the planet. We at Deep Green Resistance put no faith in this line of reasoning; the UK government has not defended the planet thus far, and there is no evidence that it will. Based on this divergent analysis, our goal is different. Rather than political-social, our goal is physical-material: we advocate for strategic dismantling of global industrial infrastructure.

Please share your thoughts in the comments.

By Graeme Hayes and Oscar Berglund / The Conversation

A new direct action group calling itself the Tyre Extinguishers recently sabotaged hundreds of sports utility vehicles (SUVs) in various wealthy parts of London and other British cities. Under cover of darkness, activists unscrewed the valve caps on tyres, placed a bean or other pulse on the valve and then returned the cap. The tyres gently deflated.

Why activists are targeting SUVs now can tell us as much about the failures of climate policy in the UK and elsewhere as it can about the shape of environmental protest in the wake of Extinction Rebellion and Insulate Britain.

The “mung bean trick” for deflating tyres is tried and tested. In July 2008, the Oxford Mail reported that up to 32 SUVs were sabotaged in a similar way during nocturnal actions in three areas of the city, with anonymous notes left on the cars’ windscreens.

In Paris in 2005, activists used bicycle pumps to deflate tyres, again at night, again in affluent neighbourhoods, again leaving anonymous notes. In both cases, activists were careful to avoid causing physical damage. Now it’s the Tyre Extinguishers who are deflating SUV tyres.

Though the actions led by the Tyre Extinguishers have numerous precedents, the group’s recent appearance in the UK’s climate movement does mark a change of strategy.

Extinction Rebellion (XR), beginning in 2018, hoped to create an expanding wave of mobilisations to force governments to introduce new processes for democratically deciding the course of climate action. XR attempted to circumvent existing protest networks, with its message (at least initially) aimed at those who did not consider themselves activists.

In contrast, activists in the Tyre Extinguishers have more in common with groups that have appeared after XR, such as Insulate Britain, whose members blockaded motorways in autumn 2021 to demand government action on the country’s energy inefficient housing. These are what we might call pop-up groups, designed to draw short-term media attention to specific issues, rather than develop broad-based, long-lasting campaigns.

After a winter of planning, climate activists are likely to continue grabbing headlines throughout spring 2022. XR, along with its sister group, Just Stop Oil, threaten disruption to UK oil refineries, fuel depots and petrol stations. Their demands are for the government to stop all new investments in fossil fuel extraction.

The Tyre Extinguishers explicitly targeted a specific class of what they consider anti-social individuals. Nevertheless, that the group’s action is covert and (so far at least) sporadic is itself telling.

In his book How to Blow up a Pipeline, Lund University professor of human ecology Andreas Malm asked at what point climate activists will stop fetishising absolute non-violence and start campaigns of sabotage. Perhaps more important is the question that Malm doesn’t ask: at what point will the climate movement be strong enough to be able to carry out such a campaign, should it choose to do so?

Given the mode of action of the Tyre Extinguishers, the answer on both counts is: almost certainly not yet.

The moral economy of SUVs

For now, the Tyre Extinguishers will doubtless be sustained by red meat headlines in the right-wing press. It’s still probable, however, that the group will deflate almost as quickly as it popped up: this is, after all, what has happened with similar groups in the past.

The fact that activists are once again employing these methods speaks to the failure of climate policy. Relatively simple, technical measures taken in the early 2000s would have solved the problem of polluting SUVs before it became an issue. The introduction of more stringent vehicle emissions regulations, congestion charging, or size and weight limits, would have stopped the SUV market in its tracks.

SUVs are important because they are so much more than metal boxes. Matthew Paterson, professor of international politics at the University of Manchester, argues that the connection between freedom and driving a car has long been an ideological component of capitalism.

And Matthew Huber, professor of geography at Syracuse University in the US, reminds readers in his book Lifeblood that oil is not just an energy source. It generates ways of being which become culturally and politically embedded, encouraging individualism and materialism.

Making SUVs a focal point of climate activism advances the argument that material inequality and unfettered individual freedoms are incompatible with any serious attempt to address climate change.

And here lies the crux of the conflict. The freedom of those who can afford to drive what, where and when they want infringes on the freedoms of the majority to safely use public space, enjoy clean air, and live on a sustainable planet.

Graeme Hayes is a reader in Political Sociology at Aston University. Oscar Berglund is a lecturer in International Public and Social Policy at the University of Bristol.

by DGR News Service | May 12, 2022 | ACTION, Property & Material Destruction

Oral arguments for a federal appeal in the high profile case of environmental activist Jessica Reznicek will be heard by the 8th circuit court of appeal on May 13. In a defining moment for the climate justice movement and for all civil rights, the court will decide whether or not to uphold a “domestic terrorist enhancement” that an Iowa court applied to Reznicek’s prison sentence. Reznicek is expected to argue that the terrorism enhancement was both illegally and unjustly applied.

In 2016, Jessica Reznicek took action to stop the construction of Dakota Access Pipeline by dismantling construction equipment and pipeline valves. In 2021 she was sentenced to 8 years in prison with a domestic terrorism enhancement.

Under normal conditions Jess would have been sentenced to 37 months, but the terrorism enhancement resulted in a sentence of 96 months. She was also ordered to pay $3.2 million in restitution to Energy Transfer corporation.

The appeal is supported by the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), National Lawyers Guild, Water Protectors Legal Collective, and the Climate Defense Project. “If Jessica Reznicek’s acts can be punished as terrorism,” says an amicus brief filed by CCR, “the United States will have moved so far past the international consensus as to be operating in a completely different realm.”

- WHAT: Oral arguments for federal appeal, U.S.A. v. Jessica Reznicek. Case # 21-2548

- WHO: United States Court of Appeals- 8th Circuit, DAPL activist Jessica Reznicek

- WHEN: Friday, May 13 at 8:30 CST

- WHERE: St Paul, Minnesota United States Court, Courtroom 5A. Closed to the public in person. Listen in by calling 1-888-363-4749 Code 4423562. Jessica Reznicek is 5th on the docket.

In 2017 Jessica Reznicek and a partner from the Catholic Worker Movement publicly claimed responsibility for acts of vandalism against the Dakota Access Pipeline. In February, 2021 she pled guilty to a single count of Conspiracy to Damage an Energy Facility. In June, 2021 an Iowa judge imposed a “terrorism enhancement” at the prosecution’s request and sentenced Reznicek to 8 years in prison with restitution of over $3 million to be paid to Energy Transfer LLC. No one was injured by Reznicek’s acts of civil disobedience.

Although federal courts have ruled the Dakota Access Pipeline was constructed illegally, excessive punishment for people like Jessica, who tried to stop it, is on the rise – and scrutiny is growing of fossil fuel industry influence in the process. Wrote Jessica in a 2021 statement to the court, “I am not a political person. I am certainly not a terrorist. I am simply a person who cares deeply about an extremely basic human right that is under threat: Water.”

To support Jess’s legal case, visit https://supportjessicareznicek.com/.

Photo: Occupy Des Moines – Day 113: Jess Reznicek Arrested, by Justin Norman. Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

by DGR News Service | May 9, 2022 | ACTION, Movement Building & Support

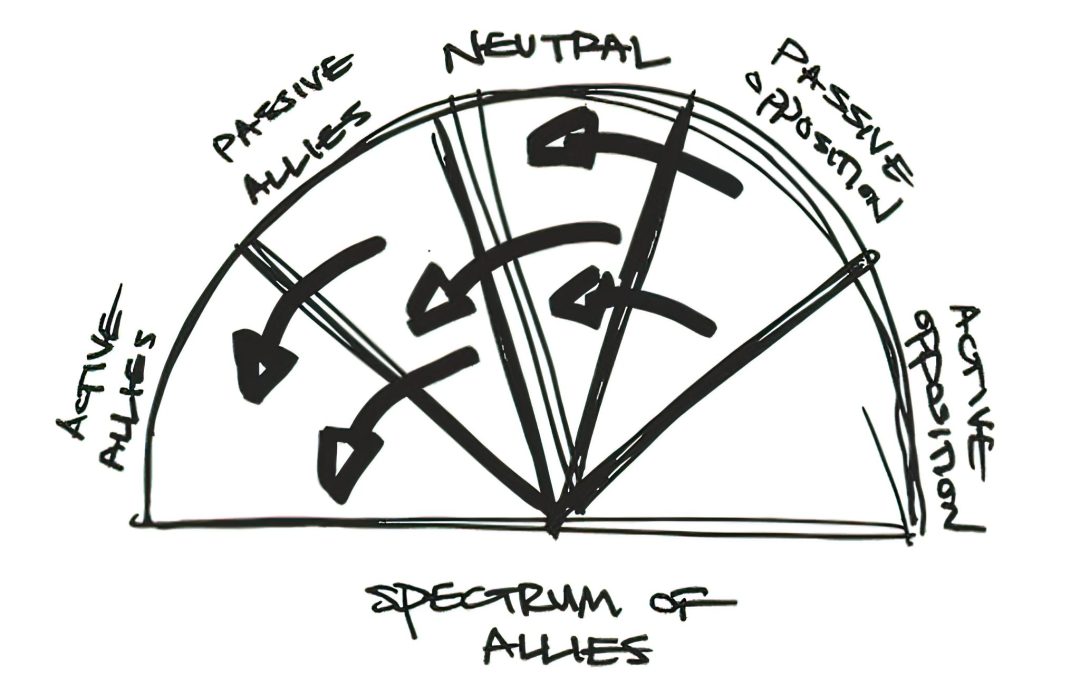

Editor’s note: The following conceptual tool is designed to help community organizers to categorize community groups, businesses, government bodies, and individuals along a “spectrum of allies.” This exercise teaches a fundamental tenet of community organizing: that our goal is not only to find people who agree with us fully, but to gradually shift those who disagree with us into greater political alignment.

We use this tool regularly in Deep Green Resistance training programs and campaigns, and encourage you to do so as well.

By Nadine Bloch

Introduction

Movements seldom win by overpowering the opposition; they win by shifting support out from under it. Use a spectrum-of-allies analysis to identify the social groups (students, workers) that are affected by your issue, and locate those groups along a spectrum, from active opposition to active allies, so you can focus your efforts on shifting those groups closer to your position. Identifying specific stakeholders (e.g. not just students, but students at public colleges; not just workers, but domestic workers) can help you identify the most effective ways of moving different social groups closer to your position, in order to win your campaign.

When mapping out your campaign, it is useful to look at society as a collection of specific communities, blocs, or networks, some of which are institutions (unions, churches, schools), others of which are less visible or cohesive, like youth subcultures or demographic groupings. The more precisely you can identify stakeholders and impacted communities, the better you can prepare to persuade those groups or individuals to move closer to your position. You can then weigh the relative costs and benefits of focusing on different blocs.

Evaluating your spectrum of allies can help you avoid some common pitfalls. Some activist groups, for instance, only concern themselves with their active allies, which runs the risk of “preaching to the choir” — building marginal subcultures that are incomprehensible to everyone else, while ignoring the people you actually need to convince. Others behave as if everyone who disagrees with their position is an active opponent, playing out the “story of the righteous few,” acting as if the whole world is against them. Yet others take a “speak truth to power” approach, figuring that through moral appeal or force of logical argument, they can somehow win over their most entrenched active opponents. All three of these extreme approaches virtually guarantee failure.

Movements and campaigns are won not by overpowering one’s active opposition, but by shifting each group one notch around the spectrum (passive allies into active allies, neutrals into passive allies, and passive opponents into neutrals), thereby increasing people power in favour of change and weakening your opposition.

For example, in 1964 in the U.S., the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), a major driver of the African-American civil rights movement in the racially segregated South, realized that in order to win desegregation and voting rights for African Americans, they needed to make active allies of sympathetic white northerners. Many students in the North were sympathetic, but had no entry point into the movement. They didn’t need to be educated or convinced, they needed an invitation to enter the struggle. (Or in the spectrum-of-allies schema, they needed to be moved from passive allies into active allies.) Moreover, these white students had extended communities of white families and friends who were not directly impacted by the struggles of African-American southerners. As the struggle escalated, these groups could be shifted from neutral to passive allies or even active allies.

Based on this analysis, the SNCC made a strategic decision to focus on reaching neutral white communities in the North by engaging sympathetic white students in their Freedom Summer program. Busloads of students travelled to the South to assist with voter registration, and many were deeply radicalized in the process. They witnessed lynchings, violent police abuse, and angry white mobs, all a response to black Southerners simply trying to exercise their right to vote.

Many wrote letters home to their parents, who suddenly had a personal connection to the struggle. This triggered another desired shift: Their families became passive allies, often bringing their workplaces and social networks with them. The students, meanwhile, returned to school in the fall as active allies, and proceeded to organize their campuses — more shifts in the direction of civil rights. The result: a profound transformation of the political landscape.

This cascading shift of support wasn’t spontaneous; it was part of a deliberate movement strategy that, to this day, carries profound lessons for other movements.

How to use

Use this tool to identify the constituencies that could be moved one notch along the spectrum, as well as to assess the relative costs of reaching, educating, or mobilizing each of these constituencies. Do not use this tool to identify your arch enemies and go after them — it’s the people in the middle you’ll most often want to focus on. The groupings or individuals you identify should be as specific as possible: not just unions, for instance, but specific unions. The more specific you can be, the better this tool will serve you.

Here’s how to do a spectrum-of-allies analysis:

1. Set up a “half-pie” drawing (see diagram).

Label the entire drawing with the name of the specific movement or campaign you are discussing, and put yourself on the left side, with your opposition on the right side.

2. Divide the half-pie into five slices:

- active allies, or people who agree with you and are fighting alongside you;

- passive allies, or people who agree with you but aren’t (yet) doing anything about it;

- neutrals, or the unengaged and uninformed;

- passive opposition, or people who disagree with you but aren’t actively trying to stop you; and

- active opposition, or people who not only disagree with you, but are actively organizing against you.

In the appropriate wedges, place different constituencies, organizations, or individuals. Spend a significant amount of time brainstorming the groups and individuals that belong in each of the sections. Be specific: list them with as many identifying characteristics as possible. And make sure to cover every wedge; neglecting sections will limit your strategic planning and your potential effectiveness.

3. Step back and see if you’re being specific enough

For every group or bloc you listed in the diagram, ask yourself whether you could be more specific — are there more adjectives or qualifiers you could add to give more definition to the description? You might be tempted to say “mothers,” but the reality might be that “wealthy mothers who live in gated communities” might belong in one wedge, and “mothers who work as market vendors” would belong in another. The more specific you can be, the better this tool will serve you.

4. Identify what else you need to know.

When you come up against the limits of your knowledge, make sure to start a list of follow-up questions — and commit to doing the research you’ll need to get the answers.

Combine with other tools

The spectrum of allies can also work well in combination with other methodologies:

- First, use pillars of power to map out the biggest forces at play.

- Combine with a SWOT matrix in order to help you identify all key constituencies.

- Follow up with points of intervention in order to identify tactics and actions to engage the key constituencies you’ve identified.

Nadine Bloch is currently Training Director for Beautiful Trouble, as well as an artist, political organizer, direct action trainer, and puppetista. If you have a question for Nadine about this tool you can contact her via the form at the bottom on the Beautiful Uprising Spectrum of Allies article.

This article is published under the Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA license. Small portions of the original article were omitted for clarity.

by DGR News Service | May 1, 2022 | ACTION

Editor’s note: The ability to work with others who we may disagree is fundamental to organizing in a socially fractured, multi-polar world. But doing so is difficult, distasteful, and increasingly rare in our filter-bubble modern experience, where people we disagree with are purged in service of the creation of ideological echo chambers. Today’s essay speaks to the necessity and challenges of such coalition-building.

Before we begin, we would like to share with you some actionable advice for coalitions. Building principled alliances depends on a series of steps that must be undertaken with intelligence and great care:

1. Movement Building. You cannot build an alliance as an individual. Alliances are built between organizations. We will assume here you have already done the work of identifying the core issues you are trying to address, articulating your core values, and bringing together a team/organization to take action.

2. Objectives. Alliances depend on you clearly understanding what you are trying to achieve. Determine your objectives. Ensure they are SMART and practical. You may also wish to sequence objectives along a timeline towards your broader strategic goals.

3. Understand the Political Context. Conduct a spectrum of allies exercise. Identify communities, individuals, and organizations who are involved in the situation or may be swayed to take part, and how sympathetic they are to your perspective.

4. Determine Potential Allies. Determine which organizations you will focus on for alliance building. Usually, this is not the “easy allies” who will work with you regardless of what you do. Instead, pivotal allies are often found among the ranks of those who are ambivalent or opposed to your organization in some way. Focus on key individuals, usually either formal or informal leaders. Research these people and identify areas of overlap, shared values, and how to effectively communicate with them.

5. Build Relationships and Negotiate. Talk with potential allies. Begin to build a relationship. Do not gloss over disagreements, but focus on areas of mutual benefit and overlapping values. Propose specific ways work together towards shared goals. Keep in mind that collaboration can fall along a spectrum from public to private, that political considerations may prevent certain approaches, and that building trust takes time.

By Jaskiran Dhillon / ROAR Magazine

They called it the heat dome.

The hottest temperatures ever recorded in the US Pacific Northwest and far southwest Canada appeared in the summer of 2021 with the force of an invisible, slow-motion siege. Meteorologists tracking the silently rising tidal wave of heat broadcasted maps painted in shades of crimson, alerting a sleeping public to a summer gone blazing red. The headlines said it all: “This Summer Could Change Our Understanding of Extreme Heat,” “Sweltering Temperatures Expected Across U.S. Due to Heat Dome,” and “Western Canada Burns and Deaths Mount After World’s Most Extreme Heat Wave in Modern History.”

Created through a high pressure system that causes the atmosphere to trap very warm air — and precipitated, in part, through heat emerging from increasingly warming oceans — a heat dome produces extreme temperatures at ground level that can persist for days or even weeks. In British Columbia, Canada, thermometers were registering the air at an alarming 49.6 degrees Celsius, with similar highs in the states of Washington and Oregon, immediately south of the border, exposing US and Canadian residents to the type of extreme weather events countries in the Global South have been experiencing for years. But this kind of heat does not just live in the air that we breathe — it envelopes everything it touches, leaving a trail of death, destruction, and urgent questions about the future.

For climate scientists who have been studying the intensification of heat wavesover the last decade, the results of the heat dome were predictably devastating. The British Columbia Coroners Service identified 569 heat related deaths between June 20 to July 29, and 445 of them occurred during the heat dome. A human body exposed to severe and relentless heat is a body under duress, a body working overtime: when subjected to an elevation in air temperatures, our bodies draw additional blood to the skin to dissipate heat — a natural cooling system designed to maintain optimal body temperature. This process becomes more strained when the temperature continues to rise, without the reprieve of cooling; oxygen consumption and metabolism both escalate, leading to a faster heart rate and rapid breathing. Above 42 degrees Celsius, enzyme and energy production fail and the body is in danger of developing a systemic inflammatory response. Eventually, multi-system failure can occur.

And humans were not the only beings impacted. According to an article published in The Atlantic in July 2021, billions of mussels, clams, oysters, barnacles, sea stars and other intertidal species also died. A number of land-based species also fared badly, buckling in the sweltering and suffocating air, creating a dystopic tale of “desperate and dying wildlife.”

To put it plainly: the physiological stress of extreme heat on living organisms is life threatening — in particular for human beings: baking to death is a real possibility if you do not have access to cooling systems, or if you are one of the millions of people who live in parts of the world where climate change has increased your chances of exposure to extreme heat and comprehensive adaptation strategies have yet to be developed.

Our bodies are not meant to work this hard under these kinds of conditions — and neither is the planet.

A Profound Imbalance of Power

So how did we arrive here? A rapid attribution analysis of the heat dome conducted by a global team of scientists revealed that the occurrence of this kind of heat wave was virtually impossible without human-caused climate change. Their results came with a strong warning: “our rapidly warming climate is bringing us into uncharted territory that has significant consequences for health, well-being and livelihoods. Adaptation and mitigation are urgently needed to prepare societies for a very different future.” The situation is only expected to get more dire — three billion people could live in places as hot as the Sahara by 2070 unless we address climate change with radical action and address it now.

The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, released in August 2021, mirrors a similarly grave picture of our current climate reality and forecast of what lies ahead. In a bold, oppositional move against national governments who have edited the findings of such assessments in the past, a group of scientists leaked the third part of the report which reveals, in unequivocal terms, how fossil fuel industries propped up by state governments are some of the largest contributors to our current environmental condition and what needs to be done to shift course.

The report reminds us that human influence has warmed the climate at a rate that is unprecedented in at least the last 2000 years with a near-linear relationship between cumulative anthropogenic CO2 emissions and the global warming they cause. This means that we are no longer waiting for the arrival of climate change — it is here. It lives in the stifling hot air we breathe during unanticipated heat waves. It is the reason droughts are becoming more severe and at the same time flooding is driving millions of peoples’ lives into chaos, precariousness, and displacement. It explains why Arctic ice has reached its lowest levels since at least 1850. Ocean acidification exists because of it. And it is the driver behind environmental conditions that are expected to produce 200 million climate migrants over the next 30 years. We do not need more evidence. The science could not be more clear.

Human influence has warmed the climate at a rate that is unprecedented in at least the last 2000 years.

The answer to how we ended up here, however, cannot be collapsed into a homogenized “all of us are to blame” scenario that does little to differentiate how countries like the United States and other western nations have produced the vast majority of the carbon emissions that have led to this point of immense and disastrous planetary change. The US has contributed more to the problem of excess carbon dioxide than any other country on the planet, with the largest carbon footprints made by wealthy communities — the higher the household income, the greater the emissions. In fact, a Scientific American article explains that the United States, with less than 5 percent of the global population, uses about a quarter of the world’s fossil fuel resources — burning up nearly 23 percent of the coal, 25 percent of the oil, 27 percent of the aluminum and 19 percent of the copper.

A recent Oxfam report, Confronting Carbon Inequality, provides staggering revelations about the way correlations between wealth and carbon emissions extend out to the global context: the richest 1 percent on the planet are responsible for more than double the emissions of the poorest half of humanity, and the richest 10 percent in the world are accountable for over half of all emissions. Wealthy individuals and communities, though, are not the only source of dangerous and excessive carbon emissions — global corporations dedicated to the ongoing development and flourishing of fossil fuel energy infrastructure are also a major, if not the largest, part of the problem.

If we zoom in even further, it becomes apparent that the relationship among racial capitalism, colonialism and climate change lies at the center of a critical understanding of the Anthropocene given that colonialism and capitalism together laid the groundwork for the development of carbon intensive economies that have prioritized capitalist accumulation — in all of its destructive forms — at the expense of everything else. As Potawatomi philosopher Kyle Whyte explains, with respect to the specific experiences of Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island, “the colonial invasion that began centuries ago caused anthropogenic environmental changes that rapidly disrupted many Indigenous peoples, including deforestation, pollution, modification of hydrological cycles, and the amplification of soil-use and terraforming for particular types of farming, grazing, transportation, and residential, commercial and government infrastructure.”

These critiques are not new: Indigenous leaders throughout the world have been sounding the alarm about impending ecocide derived from the never-ending cycle of extraction and consumption for as long as settler colonies like the United States have been in existence. They have also reminded us that other kinds of worlds are possible, worlds that are built on care, reciprocity, interdependence and co-existence as opposed to structural violence, dispossession and domination.

Not surprisingly, then, a social, political and economic arrangement of our world that is anchored to colonialism and imperialism has resulted in massive disparities in terms of disproportionate impact — race, class and gender are deeply woven into the experience and violence of climate catastrophe. In the Global South, the crisis has been producing perilous and deadly climate-related events in numerous countries for over a decade, well preceding the notable arrival of the heat dome in the United States and Canada in the summer of 2021.

In Sudan, for example, temperatures are consistently rising, water is becoming more scarce and severe droughts are commonplace, producing major problems with soil fertility and agriculture. Southern Africa is warming at twice the global rate: 2019 alone saw 1200 climate related deaths. Bangladesh, often referred to as “ground zero for climate change” despite having contributed as little as 0.09 percent to global cumulative CO2 emissions, has experienced a major surge in flooding which has resulted in the destruction of millions of homes, created numerous obstacles in crop production, and caused an alarming escalation in food insecurity.

People all over the globe are living on the front lines of a planet-wide crisis that has been produced far outside the boundaries of their own communities. To make matters worse, climate researchers from the Global South face multiple challenges obtaining funding for their projects and getting their research in front of the global community of scientists — largely from Western states — who are driving the agenda of adaptation. COP26 was illustrative of this problem of access — given the uneven distribution of vaccines, many climate organizers and scientists from the Global South, as well as Indigenous leaders, were unable to attend the conference that had been heralded as the “last chance to save humanity.” Perhaps this was one of the reasons that COP26 was such a catastrophic failure. There is a profound power imbalance within the context of the climate crisis which sits alongside vital questions about social inequality and shared responsibility.

A Framework of Internationalism

In the face of such grim and devastating projections, sidestepping into the hopelessness trap seems like the easiest place to land, but millions of people across the globe do not have the luxury of retreat or denial — and if we consider the long game, none of us do. How do those of us who are determined to act on climate change think about what it means to actualize global solidarity and mass mobilization within the context of this historical moment where everything is at stake? What are some of the political guideposts that should lie at the heart of what it means to be a climate organizer?

One thing that immediately comes to mind is that our mobilizations around climate change and environmental justice must be guided by an internationalist framework that is both anti-colonial and anti-capitalist. A consistent focus on the ways that “here is deeply connected to there and there is deeply connected to here” necessitates that we never lose sight of the fact that the vast majority of people in the world who are staring down the devastation of climate change at this moment have not had a hand in producing it.

We can take our cue from youth climate organizers in this regard. In Philadelphia, as a case in point, activists with Youth Climate Strike have been mobilizing protests in the streets while operating with a direct line to internationalism — linking struggles for environmental justice in the neighborhoods in which they live with the devastation of the climate crisis in the Global South. Their organizing transcends geographical boundaries, demanding that those of us in the Global North open our eyes and act on our responsibility to communities locally and to the rest of the world for a climate catastrophe that is, in large part, made in the United States.

A framework of internationalism, however, must also include foregrounding a critical analysis of the ways that racial capitalism continues to wreak havoc on the planet. Indeed, countries like the US function as part of a much larger constellation of imperial projects that produce great suffering, initiate catastrophic death, and remake ecologies and modes of relationship in order to facilitate the movement of capital. The Zapatistas knew this in 1994 when they made their “First Declaration from the Lacandon Jungle.” The Standing Rock Sioux stood in opposition to this when they launched their epic battle against the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016. And communities in Guyana are pushing back against this as they organize in response to the expansion of Exxon’s oil extraction which expects to send more than two billion metric tons of CO2 into the atmosphere.

A framework of internationalism must also include a critical analysis of the ways that racial capitalism continues to wreak havoc on the planet.

A related reason that an internationalist and anti-colonial framework is so vital in this moment of climate organizing is that imperialism goes hand in hand with environmental destruction. That is to say, imperial projects such as the United States’ 20-year colonial occupation of Afghanistan has not only left countless Afghan citizens in a situation of immense danger and precariousness since the reinstatement of the Taliban, but has also left the country in a state of environmental wreckage. This destruction is evident in rampant deforestation, which proliferated during the turbulence of such a long war, and a rise in toxic air pollutants that were released by US armed forces through trash burning — and other military activities — and are making Afghani people chronically ill because they increase the risk of cancer and other diseases. Defunct military bases also require environmental remediation before the land can be used for life giving instead of life taking purposes.

A recent report from Brown University’s The Cost of War Project confirms that the United States spends more on the military than any other country in the world — substantially more than the combined military spending of Russia and China. The use of military force requires a great deal of energy, and most of it in the form of fossil fuels. As a result of this monstrous commitment to militarization, the US war machine is one of the largest polluters on the planet with this cataclysmic damage extending out to the other colonial projects supported through US tax dollars.

The war-finance nexus ties the United States and Canada to Africa, to the Middle East, to South America, to Asia; in short, to all places where international finance capital moves. The billions of dollars that have gone to support the Israeli military, for example, has enabled immense environmental ruination in Palestine. Bombs and related lethal weaponry are intended to destroy, not to build. And the afterlife of such destruction continues to impact the air, land, water, plants, animals and people who have lived under conditions of war for years, even after a war ostensibly comes to an end or an occupying force ostensibly “withdraws.” This means that a robust climate justice movement must necessarily include demilitarization in order for an internationalist agenda of ecological justice and sustainability to be realized.

Multi-Racial and Anti-Colonial Feminist Coalition Building

In order to make internationalism happen in the spaces and places of climate organizing, however, coalitions must also be part of the answer. Those of us who are the most privileged have a responsibility to do the hard work of building multi-racial and anti-colonial feminist coalitions between different social movements collaborating across political and geographical borders — multi-issue coalitions that foster self-reflexivity and allow us to understand one another better, to decipher the ways that our worlds have become co-constituted through a series of lived experiences and historical material relations.

Racial capitalism, as it is fueled by colonial and imperial projects, works through all of us, it becomes entrenched in even the most seemingly benign social practices and ways of being, it shapes our collective and individual memories about who we are. In essence, it plays with what it means to be human — how we develop relationships to one another and the world around us, how we eat, breath and love — part of the labor we have to commit to doing has to do with understanding how this happens in order to identify the things that bind us together and determine how best to unify in a collective struggle to save the planet.

In this regard, a crucial aspect of the climate justice movement should involve creating platforms where people can engage in debates and dialogues about power and history in their everyday mobilizing efforts. Through these interactions, people can knit together their social positions and experiences of oppression, marginalization and resistance while being attentive to the specificities of particular struggles. This resonates with Afro-Caribbean scholar and activist Jacqui Alexander’s call for feminists of color to become “fluent in each other’s histories” and Black radical feminist Angela Davis’s plea to foster “unlikely coalitions.”

Multi-racial and anti-colonial feminist coalition building of this sort has the ability to speak loudly to a politics of interdependence; to become a powerful counter to political echo chambers. It allows us to set forth a challenge to (re)educate ourselves and confront, head on, blind spots about history and present and to explore how nationality and citizenship status, class, race, gender, sexuality, age, and ability, among other factors, produce social realities and lived experiences that are tied to one another but also very unequal. We can start to see linkages between social issues and communities all over the world that are often positioned as separate and removed from each other and prompt those in the Global North to adjust their organizing efforts, networking, and platform building in a manner that addresses these inequalities in practical ways to begin to shift power dynamics.

Wherever these coalitions come into being, Indigenous leaders must play a fundamental role given global histories of land dispossession and ongoing colonial occupations, and because they offer critical guidance and anti-colonial blueprints for how we can actively shape a decolonizing path moving forward.

Multi-racial and anti-colonial feminist coalition building has the ability to speak loudly to a politics of interdependence.

Put simply: in order to push our politics of solidarity further, we have to refuse the desire to isolate as well as the messiness and limitations of identity politics that will always seek to divide us instead of bringing us together. We need people who are pushing the boundaries of environmental movements to speak across divergent but shared colonial histories, contemporary forms of racial state violence and the ongoing devastation of settler colonialism, colonial gender violence and anti-Black racism in places like the United States. And we also need people who can identify the ways these forms of colonial violence exist as part of a larger imperial web that reaches far beyond national borders. African American composer and activist Bernice Reagan’s oft cited speech, “Coalition Politics: Turning the Century” offers counsel here about why this matters so much: we need coalitions because movements that exist in relation to one another are stronger for it. We need them to ensure survival.

Perhaps what we will gain from multi-racial and anti-colonial feminist coalitions, then, is an emerging architecture of decolonization and practice of solidarity that produces new political ecologies reflective of this historical moment. In turn, this holds the potential to illustrate points of alignment and intersection, thus enabling the identification of common political goals and paving the way for global unification across distinct social and historical geographies. States do their best to carry out projects of colonialism and imperialism, but the people are never conquered. As such, those of us persevering for a better world must also conduct our political organizing around climate change in a way that actively works to bring people together, addressing colonialism at home and abroad.

A Revolutionary Plan of Action

Finally, because organizing against climate change is a future-oriented project, it is one that demands and requires durable and deep relationships. This means that we need to commit to resurrecting the idea and practice of solidarity by pulling it back from the clutches of oversimplification and empty overuse. In the parlance of Palestinian writer Steven Salaita, solidarity requires ethical commitments to function and does not involve appropriation. It is performed in the interest of better human relationships and for a world that allows societies to be organized around justice rather than profit. This is the kind of solidarity we must seek to bring into existence.

We have to ask ourselves, then, to identify the processes and practices that will allow us to build real understanding while centering a common interest of survival that is informed by notions of reciprocity, empathy and humility, reminiscent of the Zapatista’s idea of “caminar preguntando” — asking questions while walking. We have to be able to see one another and to recognize the individual and collective struggles that taken together are threatening the continuation of life itself. We have to be willing to listen and receive a rigorous education and simultaneously be eager to teach, to share, to trust and to invest ourselves in a future that elevates mutual validation and recovers a sense of dignity through resistance. Philosopher Esme Murdock reminds of this (re)alignment so powerfully when she says, “[t]here is a whole, messy, and beautiful place waiting for us where we fuck up and make it right and fuck up and make it right by holding each other responsible in the strength and terror of becoming and making kin.”

A relationality of this type has the power to activate, it moves us towards political organizing and praxis because it reminds us that we are, in fact, capable of crafting relationships with our relatives, human and other-than-human, that are built on mutual respect and interconnection. But to do this, we have to be honest with ourselves about the culpabilities and responsibilities we carry and be open to altering our comprehension of the problems we are facing and in turn, be ready to shift our ideas of “solutions” that will be most effective in the context of a rapidly shrinking timeline. We have to both harness and give up some of our power.

Science alone will not save us, and neither will government policy, UN meetings or climate summits where we expect “world leaders” to stand up and unify around the changes that we so desperately need. We cannot ameliorate this problem by promoting better consumer choices that privilege individual behavioral change or by supporting corporations pedaling “sustainable products.” There is no magical technology that is going to allow things to return to “normal,” the green billionaires do not have the answers, and there is no fantasy island that we can swim to that will offer a climate reset.

We require a revolutionary plan of action that is generated by a global peoples’ movement and guided by a set of shared political commitments and ways of relating to one another that can withstand the immense uncertainty of this moment, a plan that is grounded in the dynamics of the here and now and committed to a just future liberated from the shackles of climate apocalypse. The road forward is not easy, but making the decision to step onto it is perhaps the thing that matters most in this moment because it signals an attachment to the idea that something else is possible, that we have not conceded or given up, that we are willing to keep trying. And in the end, our ability to stand together is one of the greatest weapons of hope and resistance we have.

A version of this article will be included in Jaskiran Dhillon’s latest book Notes on Becoming a Comrade: Solidarity, Relationality, and Future-Making, forthcoming in 2022 with Common Notions Press.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash.

by DGR News Service | Apr 25, 2022 | ACTION, Movement Building & Support, The Solution: Resistance

By Max Wilbert

We are living in an ecological catastrophe. Our world is being killed before our eyes. This hurts. And so for many people, their response is either apathy, complete emotional shutdown, or a nihilistic embrace of powerlessness.

There is another option. While our power to change the course of ecological collapse is indeed limited, limited is different from non-existent. The truth is, we do have power. And we can change the world. No, our power is not limitless. No, the world will not change easily. And no, we cannot fix everything. Some things are broken beyond fixing. But these difficulties do not absolve us of responsibility.

There is an old warrior’s saying that “duty is heavier than a mountain, and death is lighter than a feather.” The duty of humans with moral conscience in this era is heavy indeed. And yet, what would we be if we abandoned this world to its fate? If we abandoned our forests, our oceans, our mountains? If we abandoned our non-human relatives? If we abandoned our communities and future generations of children? What would we be, then?

Some people argue that humanity is simply a cancer. That we will destroy ourselves. That our nature is fundamentally destructive. That our actions have proven us unfit to survive in the long-term, unfit to participate in the community of life, which we are destroying.

But if human destructiveness is one part of our potential, then humans defending the land is another. Those who defend the land are part of the immune system of the world. We are defenders of wholeness. We bring balance. We are the consciousness of the Earth, our bones like mountains, our blood like rivers. We are an evolutionary force, an outgrowth of the planet itself, taking action to defend our community.

And we will not give up, because ultimately, to abandon responsibility is to abandon our own souls. There is only one way we can guarantee the worst possible outcome for the future: if we take no action at all.

And so today, I wish to thank the activists and land defenders of the world. Your hearts are the conscience of our society. Your tears are our prayers. Your dedication is the salvation of life. Your effort is not in vain. You are valuable.

Thank you.

by DGR News Service | Apr 1, 2022 | ACTION, Culture of Resistance, Worker Solidarity

Editor’s note: Luddism is often dismissed as “backwardness,” but it is actually a more advanced, considered, and wise position on technology. To be a Luddite is to stand with workers and the natural world against the death march of technology. This essay is a general introduction to the Luddites.

However, we disagree with the author when he argues that modern technology is neutral and that “it’s how such technology is used” that determines its moral character. This view is fundamentally anthropocentric; it’s only possible when you discount the natural world and believe humans are more important than other species. For a more deeply developed critique of technological escalation (we do not refer to this phenomenon as “progress”), we recommend exploring the work of Lewis Mumford, Vine Deloria Jr., Derrick Jensen, Vandana Shiva, Chellis Glendinning, Ivan Illich, Jack D. Forbes, Langdon Winner, and other critics of technology and civilization.

Here at Deep Green Resistance, we use the tools of industrial civilization (such as computers and the internet) to oppose it. Some accuse us of hypocrisy. But did Crazy Horse and Tecumseh not use firearms to fight European colonization? As Arundhati Roy has said, “Fighting people will choose their own weapons.” We see a place in our movement for both principled rejection of technology and the establishment of counter-cultural spaces and organizations, and for the principled use of the products of empire to dismantle empire. These efforts may seem contradictory, but they are not — they are complementary, and in Deep Green Resistance, many of us practice both at the same time.

By Jathan Sadowski / Originally published in The Conversation

I’m a Luddite. This is not a hesitant confession, but a proud proclamation. I’m also a social scientist who studies how new technologies affect politics, economics and society. For me, Luddism is not a naive feeling, but a considered position.

And once you know what Luddism actually stands for, I’m willing to bet you will be one too — or at least much more sympathetic to the Luddite cause than you think.

Today the term is mostly lobbed as an insult. Take this example from a recent report by global consulting firm Accenture on why the health-care industry should enthusiastically embrace artificial intelligence:

Excessive caution can be detrimental, creating a luddite culture of following the herd instead of forging forward.

To be a Luddite is seen as synonymous with being primitive — backwards in your outlook, ignorant of innovation’s wonders, and fearful of modern society. This all-or-nothing approach to debates about technology and society is based on severe misconceptions of the real history and politics of the original Luddites: English textile workers in the early 19th century who, under the cover of night, destroyed weaving machines in protest to changes in their working conditions.

Our circumstances today are more similar to theirs than it might seem, as new technologies are being used to transform our own working and social conditions — think increases in employee surveillance during lockdowns, or exploitation by gig labour platforms. It’s time we reconsider the lessons of Luddism.

A brief — and accurate — history of Luddism

Even among other social scientists who study these kinds of critical questions about technology, the label of “Luddite” is still largely an ironic one. It’s the kind of self-effacing thing you say when fumbling with screen-sharing on Zoom during a presentation: “Sorry, I’m such a Luddite!”

It wasn’t until I learned the true origins of Luddism that I began sincerely to regard myself as one of them.

The Luddites were a secret organisation of workers who smashed machines in the textile factories of England in the early 1800s, a period of increasing industrialisation, economic hardship due to expensive conflicts with France and the United States, and widespread unrest among the working class. They took their name from the apocryphal tale of Ned Ludd, a weaver’s apprentice who supposedly smashed two knitting machines in a fit of rage.

The contemporary usage of Luddite has the machine-smashing part correct — but that’s about all it gets right.

First, the Luddites were not indiscriminate. They were intentional and purposeful about which machines they smashed. They targeted those owned by manufacturers who were known to pay low wages, disregard workers’ safety, and/or speed up the pace of work. Even within a single factory — which would contain machines owned by different capitalists — some machines were destroyed and others pardoned depending on the business practices of their owners.

Second, the Luddites were not ignorant. Smashing machines was not a kneejerk reaction to new technology, but a tactical response by workers based on their understanding of how owners were using those machines to make labour conditions more exploitative. As historian David Noble puts it, they understood “technology in the present tense”, by analysing its immediate, material impacts and acting accordingly.

Luddism was a working-class movement opposed to the political consequences of industrial capitalism. The Luddites wanted technology to be deployed in ways that made work more humane and gave workers more autonomy. The bosses, on the other hand, wanted to drive down costs and increase productivity.

Third, the Luddites were not against innovation. Many of the technologies they destroyed weren’t even new inventions. As historian Adrian Randall points out, one machine they targeted, the gig mill, had been used for more than a century in textile manufacturing. Similarly, the power loom had been used for decades before the Luddite uprisings.

It wasn’t the invention of these machines that provoked the Luddites to action. They only banded together once factory owners began using these machines to displace and disempower workers.

The factory owners won in the end: they succeeded in convincing the state to make “frame breaking” a treasonous crime punishable by hanging. The army was sent in to break up and hunt down the Luddites.

The Luddite rebellion lasted from 1811 to 1816, and today (as Randall puts it), it has become “a cautionary moral tale”. The story is told to discourage workers from resisting the march of capitalist progress, lest they too end up like the Luddites.

Neo-Luddism

Today, new technologies are being used to alter our lives, societies and working conditions no less profoundly than mechanical looms were used to transform those of the original Luddites. The excesses of big tech companies – Amazon’s inhumane exploitation of workers in warehouses driven by automation and machine vision, Uber’s gig-economy lobbying and disregard for labour law, Facebook’s unchecked extraction of unprecedented amounts of user data – are driving a public backlash that may contain the seeds of a neo-Luddite movement.

As Gavin Mueller writes in his new book on Luddism, our goal in taking up the Luddite banner should be “to study and learn from the history of past struggles, to recover the voices from past movements so that they might inform current ones”.

What would Luddism look like today? It won’t necessarily (or only) be a movement that takes up hammers against smart fridges, data servers and e-commerce warehouses. Instead, it would treat technology as a political and economic phenomenon that deserves to be critically scrutinised and democratically governed, rather than a grab bag of neat apps and gadgets.

In a recent article in Nature, my colleagues and I argued that data must be reclaimed from corporate gatekeepers and managed as a collective good by public institutions. This kind of argument is deeply informed by the Luddite ethos, calling for the hammer of antitrust to break up the tech oligopoly that currently controls how data is created, accessed, and used.

A neo-Luddite movement would understand no technology is sacred in itself, but is only worthwhile insofar as it benefits society. It would confront the harms done by digital capitalism and seek to address them by giving people more power over the technological systems that structure their lives.

This is what it means to be a Luddite today. Two centuries ago, Luddism was a rallying call used by the working class to build solidarity in the battle for their livelihoods and autonomy.

And so too should neo-Luddism be a banner that brings workers together in today’s fight for those same rights. Join me in reclaiming the name of Ludd!

Jathan Sadowski is a Research Fellow at the Emerging Technologies Research Lab and CoE for Automated Decision-Making and Society at Monash University in Australia.