by DGR News Service | Apr 1, 2022 | ACTION, Culture of Resistance, Worker Solidarity

Editor’s note: Luddism is often dismissed as “backwardness,” but it is actually a more advanced, considered, and wise position on technology. To be a Luddite is to stand with workers and the natural world against the death march of technology. This essay is a general introduction to the Luddites.

However, we disagree with the author when he argues that modern technology is neutral and that “it’s how such technology is used” that determines its moral character. This view is fundamentally anthropocentric; it’s only possible when you discount the natural world and believe humans are more important than other species. For a more deeply developed critique of technological escalation (we do not refer to this phenomenon as “progress”), we recommend exploring the work of Lewis Mumford, Vine Deloria Jr., Derrick Jensen, Vandana Shiva, Chellis Glendinning, Ivan Illich, Jack D. Forbes, Langdon Winner, and other critics of technology and civilization.

Here at Deep Green Resistance, we use the tools of industrial civilization (such as computers and the internet) to oppose it. Some accuse us of hypocrisy. But did Crazy Horse and Tecumseh not use firearms to fight European colonization? As Arundhati Roy has said, “Fighting people will choose their own weapons.” We see a place in our movement for both principled rejection of technology and the establishment of counter-cultural spaces and organizations, and for the principled use of the products of empire to dismantle empire. These efforts may seem contradictory, but they are not — they are complementary, and in Deep Green Resistance, many of us practice both at the same time.

By Jathan Sadowski / Originally published in The Conversation

I’m a Luddite. This is not a hesitant confession, but a proud proclamation. I’m also a social scientist who studies how new technologies affect politics, economics and society. For me, Luddism is not a naive feeling, but a considered position.

And once you know what Luddism actually stands for, I’m willing to bet you will be one too — or at least much more sympathetic to the Luddite cause than you think.

Today the term is mostly lobbed as an insult. Take this example from a recent report by global consulting firm Accenture on why the health-care industry should enthusiastically embrace artificial intelligence:

Excessive caution can be detrimental, creating a luddite culture of following the herd instead of forging forward.

To be a Luddite is seen as synonymous with being primitive — backwards in your outlook, ignorant of innovation’s wonders, and fearful of modern society. This all-or-nothing approach to debates about technology and society is based on severe misconceptions of the real history and politics of the original Luddites: English textile workers in the early 19th century who, under the cover of night, destroyed weaving machines in protest to changes in their working conditions.

Our circumstances today are more similar to theirs than it might seem, as new technologies are being used to transform our own working and social conditions — think increases in employee surveillance during lockdowns, or exploitation by gig labour platforms. It’s time we reconsider the lessons of Luddism.

A brief — and accurate — history of Luddism

Even among other social scientists who study these kinds of critical questions about technology, the label of “Luddite” is still largely an ironic one. It’s the kind of self-effacing thing you say when fumbling with screen-sharing on Zoom during a presentation: “Sorry, I’m such a Luddite!”

It wasn’t until I learned the true origins of Luddism that I began sincerely to regard myself as one of them.

The Luddites were a secret organisation of workers who smashed machines in the textile factories of England in the early 1800s, a period of increasing industrialisation, economic hardship due to expensive conflicts with France and the United States, and widespread unrest among the working class. They took their name from the apocryphal tale of Ned Ludd, a weaver’s apprentice who supposedly smashed two knitting machines in a fit of rage.

The contemporary usage of Luddite has the machine-smashing part correct — but that’s about all it gets right.

First, the Luddites were not indiscriminate. They were intentional and purposeful about which machines they smashed. They targeted those owned by manufacturers who were known to pay low wages, disregard workers’ safety, and/or speed up the pace of work. Even within a single factory — which would contain machines owned by different capitalists — some machines were destroyed and others pardoned depending on the business practices of their owners.

Second, the Luddites were not ignorant. Smashing machines was not a kneejerk reaction to new technology, but a tactical response by workers based on their understanding of how owners were using those machines to make labour conditions more exploitative. As historian David Noble puts it, they understood “technology in the present tense”, by analysing its immediate, material impacts and acting accordingly.

Luddism was a working-class movement opposed to the political consequences of industrial capitalism. The Luddites wanted technology to be deployed in ways that made work more humane and gave workers more autonomy. The bosses, on the other hand, wanted to drive down costs and increase productivity.

Third, the Luddites were not against innovation. Many of the technologies they destroyed weren’t even new inventions. As historian Adrian Randall points out, one machine they targeted, the gig mill, had been used for more than a century in textile manufacturing. Similarly, the power loom had been used for decades before the Luddite uprisings.

It wasn’t the invention of these machines that provoked the Luddites to action. They only banded together once factory owners began using these machines to displace and disempower workers.

The factory owners won in the end: they succeeded in convincing the state to make “frame breaking” a treasonous crime punishable by hanging. The army was sent in to break up and hunt down the Luddites.

The Luddite rebellion lasted from 1811 to 1816, and today (as Randall puts it), it has become “a cautionary moral tale”. The story is told to discourage workers from resisting the march of capitalist progress, lest they too end up like the Luddites.

Neo-Luddism

Today, new technologies are being used to alter our lives, societies and working conditions no less profoundly than mechanical looms were used to transform those of the original Luddites. The excesses of big tech companies – Amazon’s inhumane exploitation of workers in warehouses driven by automation and machine vision, Uber’s gig-economy lobbying and disregard for labour law, Facebook’s unchecked extraction of unprecedented amounts of user data – are driving a public backlash that may contain the seeds of a neo-Luddite movement.

As Gavin Mueller writes in his new book on Luddism, our goal in taking up the Luddite banner should be “to study and learn from the history of past struggles, to recover the voices from past movements so that they might inform current ones”.

What would Luddism look like today? It won’t necessarily (or only) be a movement that takes up hammers against smart fridges, data servers and e-commerce warehouses. Instead, it would treat technology as a political and economic phenomenon that deserves to be critically scrutinised and democratically governed, rather than a grab bag of neat apps and gadgets.

In a recent article in Nature, my colleagues and I argued that data must be reclaimed from corporate gatekeepers and managed as a collective good by public institutions. This kind of argument is deeply informed by the Luddite ethos, calling for the hammer of antitrust to break up the tech oligopoly that currently controls how data is created, accessed, and used.

A neo-Luddite movement would understand no technology is sacred in itself, but is only worthwhile insofar as it benefits society. It would confront the harms done by digital capitalism and seek to address them by giving people more power over the technological systems that structure their lives.

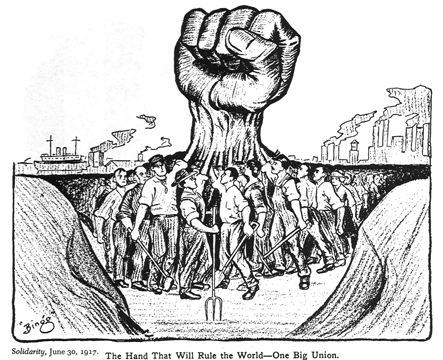

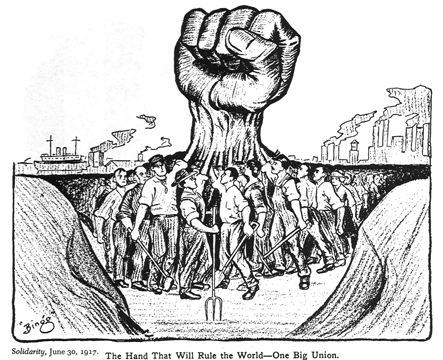

This is what it means to be a Luddite today. Two centuries ago, Luddism was a rallying call used by the working class to build solidarity in the battle for their livelihoods and autonomy.

And so too should neo-Luddism be a banner that brings workers together in today’s fight for those same rights. Join me in reclaiming the name of Ludd!

Jathan Sadowski is a Research Fellow at the Emerging Technologies Research Lab and CoE for Automated Decision-Making and Society at Monash University in Australia.

by DGR News Service | Oct 26, 2021 | Colonialism & Conquest, Repression at Home, The Solution: Resistance

This story first appeared in Building a Revolutionary Movement.

Editor’s note: As a radical environmental and social justice organization, we believe it is important to study the history of capitalism. Only by learning about all the force, the violence, the exploitation, and the class struggle involved can we understand how an insane system like industrial capitalism could eventually succeed and create the worldwide mess we are facing today.

The series about the history of trade unions in Britain has six parts. Interested readers can continue reading here:

History of trade unions in Britain part 2

History of trade unions in Britain part 3

History of trade unions in Britain part 4

History of trade unions in Britain part 5

History of trade unions in Britain part 6

By Adam H

This is a summary of “In Cause of Labour: History of British Trade Unionism” by Rob Sewell. You can find the whole book online here.

It was published in 2003 and gives a radical history of the British trade union movement from the 1700s until 2002. I’m going to summarise this book in four posts. In the fourth post I will summarise from 2002 to 2019. Rob Sewell is a Trotskyist so follows Marx, Lenin and Trotsky. So some of his terminology comes from that tradition and I’ll stick with it as it’s useful. I have left out a lot of Marxist, Leninist and Trotskyist propaganda and focused on the history plus some of Sewell’s excellent analysis. He is highly critical of the Labour Party and trade unions and I think this is a useful analysis. I’ve included links to web pages with more information on the historical events, mostly strikes, unrest, groups, organisations or parties.

In this post, part 1, I will cover the 1700s until the end of the First World War in 1918.

The birth pains 1700s

Sewell describes the Enclosure Acts in the 1700s and early 1800s, forcing large numbers of peasants off the land and into the towns looking for work and provided cheap labour for capitalist factory owners. This process created industrial capitalism and resulted in overcrowding and unsanitary conditions for the workers. There was no clear drinking water, infant mortality was high and the average age of workers in Bolton was 18, Manchester 17 and Liverpool 15.

There was a mass migration from Ireland in the first half of the 1800s. Hundreds of thousands of Irish came to work in English northern towns and cities. Employers used them to undermine wages but the Irish were more likely to make demands, speak out and enforce their demands with bad language and strikes. Many radical union leaders were Irish.

From the age of 7 children and adults worked 12-15 hours a day, 6 days a week. The intensification was increased by the introduction of large machinery. Workers existed to work or rest to recover to start work again the next day. Near Gateshead, children from the age of 7 worked 18-20 hours a day until they could not work any more, life was cheap. There were no legal protections.

Inventions revolutionised the methods of work and transformed the factory system – handlooms to power looms and gaslighting. Work was intensified further – nightshifts, double-shifts, weekend work, 24-hour work, 7 days a week, all to increase the capitalists’ profits, with the workers barely surviving. Workers were seen as old at 40. Attempts to introduce regulations about the conditions met strong resistance from the employers. Any regulations that were introduced were weakly enforced.

Workers were forced to buy what they need from ‘tommy’ shops, the factory store at extortionate prices and inferior quality. Employers paid their workers in beer as well. Many workers would end up in debt to the tommy shops.

During the 1700s workers resisted the conditions with ‘go-slows’ and ‘turn-outs’ against the “starvation wages, excessive hours and insufferable conditions.” Illegal trade clubs were formed and the state responded with anti-union legislation. The trade unions were forced underground to continue their fight to survive in self-defence.

Into the Abyss of Capitalism 1790s-1820s

The French Revolution of 1789-94 popularised the ideals of liberty, fraternity and equality. This caused a lot of fear in the British ruling class. There was also widespread bread riots and a naval mutiny in Newhaven in 1795.

The French Revolution led to the founding of Corresponding Societies from 1792 that shared democratic, radical and Jacobin ideas. Tens of thousands joined them and they were heavily repressed by the government and reactionary mobs. In response to the ongoing uprisings and spread of seditious ideas the state worked to crush them through martial law, imprisonment, public floggings, capital punishment, deportation and the suspension of Habeas Corpus (the right to a free trial). The government came down hard on the printers, publishers and sellers of seditious literature, including a stamp duty to tax newspapers and price them out of reach of the masses. This resulted in a revolt and resistance by the ‘unstamped’ press.

In 1798 there was a failed uprising in Ireland against English rule and naval mutinies in Spithead and Nore. These were severely repressed and the leaders killed.

The Corresponding Societies were driven underground resulting in oath-taking becoming a common practice. Harsh legislation was introduced to punish any form of worker organising to increase wages or decrease hours. The laws were also meant to stop employers’ conspiring together but were never enforced. These laws gave employers unlimited power to reduce wages and make conditions worse.

The British capitalist state used its full force to crush the spirit of revolt in the working class and the trade unions. Soldiers were used to putting down local disturbances. A network of army barracks was created to prevent contact between people and the soldiers. Government spies, agents and informers infiltrated the workers’ groups. Their ‘evidence’ was used to imprison organisers and leaders. A price was paid for every worker found guilty leading to false convictions.

Forcing the trade unions underground resulted in these early illegal unions enforcing iron discipline to keep out informers, which tightly bound their members together.

The Luddite unrest in 1811/12 was a response to the desperate conditions but they knew they couldn’t win. They were named after the mythical ‘General Ned Ludd.’ They destroyed employers machines and property. In response, the state increased the punishment for frame-breaking from 14 years deportation to a capital offence. Those caught in this northern and midlands resistance were dealt with harshly.

Sewell lists strike that took place under these high repressive circumstances: Scottish weavers (1812), Lancashire spinners (1818, 1826, 1830), miners on the NE coast (1810, 1830-1), Scotland (1818) and South Wales (1816, 1831). An underground General Union of Trades formed in 1818 in Manchester bringing 14 trades together. Communication between different underground trade unions across the country was also taking place.

The high levels of state repression from 1800-1815, the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the introduction of the Corn Laws, which kept bread prices artificially high, resulted in high levels of social unrest from 1815 onwards. In 1819 there was a large working-class rally in St Peter’s Field in Manchester of between 50,000 – 60,000 people. They were attacked by cavalry, with 400 being badly wounded. It is known as the Peterloo Massacre. The ‘Cato Street conspiracy’ was stopped by informants, it aimed to overthrow the government.

Trade unions continued to form: the Calico-printers, Ironfounders, the Steam Engine Makers and Papermakers. There was also widespread public agitation for the repeal of the anti-union laws. This was successful in 1824. This was a huge victory for the working class. Those in the ruling class and some workers involved in the repeal process in parliament, did so because they believed it would reduce the conflict. This was a big mistake as it resulted in a flood of strikes. So the new legislation was changed in 1825 to restrict picketing. Legal trade union activity was limited to dealing with wages and hours. Following the legalisation, hundreds of new unions and association were formed and new sections of workers became organised.

Schools of war 1820s-1830s

The 1820’s strike wave over wages mostly resulted in defeat. But it did provide important education for class struggle and lay the foundations for the establishment of the large-scale national trade unions such as the Spinners’ union 1829, Potters’ union 1831 and Builders’ in 1831-2.

Government troops were used to violently break strikes and workers responded by forming ruthless clandestine organisations that hunted down and killing traitors and informers. They also destroyed employers mills.

In 1830 the National Association for the Protection of Labour (NAPL) formed and enrolled 150 local unions in the north and midlands. It also established a weekly journal. It grew to 100,000 members but following the defeat of the Spinners’ union in 1831 and most of the local unions fighting bitter struggles, the NAPL broke up. The General Union of Carpenters and Joiners formed in the years after that with 40,000 members and fought a series of strikes.

Severe poverty and starvation outside the town and cities resulted in the 1830-31 agricultural uprisings. These started in the Southeast rural counties, with threshing machines and hayricks destroyed. They spread to the Southwest and midlands, under the name of the mythical ‘Captain Swing’. Historians have identified 1831 as the year that Britain was most close to revolution since the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Those caught were harshly punished – hangings, transported to Australia, imprisoned, flogged. The British establishment use repression when they could and when faced with mass movements gave some concessions to gain some breathing space.

Sewell describes how the mass agitation for electoral reform resulted in the government increasing the electorate through the Reform Act to those that owned property. This benefited the capitalist business owners by giving them the vote resulting in their dominance over the land aristocracy.

The Grand National Consolidation Trade Union (GNCTU) formed in 1833. It aimed to fight for day-to-day issues and also to abolish capitalist rule and bring about the revolutionary transformation of society. It quickly gained 500,000 members including many women. This led to several strikes nationally across different sectors. The Tolpuddle Martyrs were agriculture labourers that contacted the GNCTU to set up an agricultural union in Dorset. The local magistrate found out and sentenced 6 of them to 7 years transportation to Australia. A national campaign started for their freedom resulting in a 200,000 demonstration in London. The campaign was successful and after 2 years their sentences were cancelled and they returned in 1839. They were involved in the Chartist Movement. Five Glasgow cotton-spinners were transported for 7 years in 1837 resulting in equal national-wide protests to the Whig government, with a national campaign to free them.

Employers were using the ‘Document’, making workers sign it saying they would not engage in union activity, or be sacked. This resulted in many workplace lockouts and by the end of 1837, the GNCTU’s funds were depleted. This combined with differences among the leadership resulted in it breaking apart.

Sewell describes the ‘Hungry Thirties’ when the conditions for the working class were terrible. Factory legislation was introduced in 1833 but only to reduce children’s working hours to 12 and it was not enforced. The New Poor Law of 1834 made things worse, removing the limited government support to be replaced by philanthropy. The failures of the trade union movement drove workers into the ranks for the Chartist Movement.

Breaking the yoke 1830s-1840s

Chartism was a national working-class protest movement for political reform with strong support in the North, Midlands and South Wales. The movement started in 1836/7 and support was greatest in 1839, 42, 48. The Chartist Movement involved a complete spectrum of action: mass petitions, mass demonstrations, lobbies, general strikes and armed insurrection. It presented petitions with millions of signatures to parliament, combined with mass meetings to put pressure on politicians. There were splits in the movement between the old leadership that was more middle class and advocated ‘moral force’, and the new membership from working-class factory areas supported ‘physical force’.

The People’s Charter called for six reforms to make the political system more democratic:

- A vote for every man twenty-one years of age, of sound mind, and not undergoing punishment for a crime.

- The secret ballot to protect the elector in the exercise of his vote.

- No property qualification for Members of Parliament in order to allow the constituencies to return the man of their choice.

- Payment of Members, enabling tradesmen, working men, or other persons of modest means to leave or interrupt their livelihood to attend to the interests of the nation.

- Equal constituencies, securing the same amount of representation for the same number of electors, instead of allowing less populous constituencies to have as much or more weight than larger ones.

- Annual Parliamentary elections, thus presenting the most effectual check to bribery and intimidation, since no purse could buy a constituency under a system of universal manhood suffrage in each twelve-month period.

The Newport Rising of 1839 was the last large-scale armed protest in Great Britain, seeking democracy and the right to vote and a secret ballot. The army was deployed to support the police and fired on the crowd, killing and injuring. The leaders of the uprising we transported to Australia.

In 1840 the Chartist Movement formed the National Charter Association (NCA), the first working-class political party in history. It reached a total of 40,000 members. The 1842 Plug Plot Riots (also known as the 1842 general strike) started with miners in Staffordshire and spread to mills and factories in Yorkshire, Lancashire and coal mines in Dundee, South Wales and Cornwall.

The combination of the pressure from the Chartist Movement and the European revolutionary wave in 1848 forced the state to give some concessions to the working class including repealing the Corn Laws and factory legislation was passed improving the working conditions.

The “Pompous Trades” 1840s-1880s

British capitalism dramatically developed a grew in the 1850s and 1860s so it dominated the world market, with the help of the unchallenged British navy ruling the waves. This changed the unions from the earlier decades from revolutionary unions for the workers as a whole to a focus on skilled craft unions with sectional interests.

The super-profits from Britain’s industrial monopoly in the world, combined with the British Empire, meant that the ruling class could give concessions to the upper layers of the working class. This ‘divide and rule’ tactic had been perfected throughout the British Empire. In 1847 the Ten Hour Act was introduced. Sewell describes how this cultivated an ‘aristocracy of labour’, that are above the majority of workers. This privileged layer were on higher wages than most workers and developed a more conservative disposition that corresponded with their new social position. They were supportive of alliances with ‘the liberal bourgeoisie’ and were against class struggle and class independence. Sewell describes how this privileged layer grouped together in the newly formed craft unions.

An example of the craft unions or ‘new model unions’ was the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (ASE) formed in 1851 from several local craft societies. Sewell describes how these new unions had high contributions and benefits, centralisation of control, and a ‘class-collaborationist policy’ – working with the establishment.

The high dues (regular member payments) meant they could create a strong centralised organisation run by full-time officials. Instead of radical leaders from the previous decades, leaders with different characters to charge – ‘conservative-minded officials and opportunist negotiators’. They asked for a ‘fair share’ of the bosses profiles in the form of ‘friendly benefits’ such as unemployment, sickness, accident and death allowances. Sewell explains that to protect their section of privileged workers they restricted the support labour into the trades and left the rest of the workers to the mercy of the employers. They promoted prudence, temperance, enlightenment and respectability.

The respectable leadership of the new model unions were known as ‘the Junta’. They saw themselves as administrators rather than agitators and took on ‘the social character of a trade union bureaucracy’. These leaders were made to feel very important and respected by the capitalist Establishment to keep them onside.

The biggest industrial struggle since the ‘Plug Riots” of 1842, was the Preston lockout of 1853. Sewell describes the Nine Hours movement and the Nine Hours Strike in Newcastle that was successful in gaining the nine-hour day. This encouraged the movement for shorter working hours elsewhere.

During the 1860s there were many demonstrations in industrial towns demanding the vote. The Tory government introduced the 1867 Reform Act, giving the vote to urban male workers who paid rates. This doubled the size of the electorate. Women and those without property were excluded, which the majority of the working class.

In 1867, Parliament set up a Royal Commission on trade unions and following pressure from the ‘Junta’, legislation was introduced to parliament to give the unions some concessions. At this point there was no legal protection for trade union funds and strikes could be imprisoned for ‘conspiracy’ and ‘intimidation’. The new concessions reduced this slightly but workers could still be imprisoned for ‘aggravated’ breach of contract. Picketing was severely restricted and could result in tough penalties.

In 1871, the revolutionary masses of Paris took control of the city and announced ‘La Commune’ or Paris Commune. This was ruthlessly crushed by the French and German Establishment, with an estimated 20,000 killed. The Tory Prime Minister Disraeli introduced trade union reforms “from above to prevent revolution from below”. These reforms improved the financial status of unions.

Marx and Engles set up the International Workingmen’s Association (IWMA) in 1864, also known as the First International. This new international organisation received support and affiliation from several British trade unions and trade councils. Marx and the IWMA supported the Paris Commune publicly and the new model trade union leaders separated themselves from the IWMA.

During the 1860s local trade councils started forming, which was a new trade union organisation. They brought together different trade unions in a locality to work together. The trade councils had several conferences in different cities in the 1860s. The Manchester and Salford Trade Council called the first official Trades Union Congress (TUC). Sewell explains that the conservative ‘Junta’ new model union leaders were initially wary of the TUC. Following some government anti-union actions, this “forced them to lend their authority to the newly established TUC – the better to keep it under control, than risk it falling into the hands of dangerous agitators.”

Sewell describes how the two Acts in 1871 was a classic case of giving with one hand and taking away with another. The Trade Union Act of 1871 legalised trade unions in Britain for the first time and protected union funds. The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1871 deemed peaceful attempts by workers to encourage them to strike was seen as ‘coercion’ and a criminal offence. Employers of course had no restrictions on what they could do. Judges generally interpreted whatever unions did as in breach. This was threatening unions ability to operate so they decided to fight to repeal the laws and obtains ‘immunity’ for damage in the same way that business have ‘immunity’ in the form of limited liability.

From 1873 a significant campaign developed that forced the Liberal government out of office and repealed the Criminal Law Amendment Act and the Master and Servant Act. Two Acts in 1875 – Employers and Workmen Act 1875 and Conspiracy, and Protection of Property Act 1875 – made peaceful picketing legal, and breaches of contract became a civil matter, no imprisonment or fines. Judges responded by creating the civil law offence of conspiracy, making picketing illegal, and employers used this to claim damages. Sewell makes the point that any gains are always under threat and this is decided by the class balance of forces – do trade union and social movements have more power in workplaces or on the streets or do the ruling class and capitalists have more power in the form of parliamentary legislation, the courts, the police, the army and being supported by general public opinion.

The early 1870s saw the formation of the National Agricultures Labourers’ Union (NALU) to fight for better wages and conditions. This grew quickly to 150,000 members by the end of 1872. The capitalist gentry and landlords, plus the Church of England responded severely with a series of lockouts. By 1874 workers were staved back to work on the employers’ terms and the NALU collapsed.

There was a trade recession in the mid-1870s and several strikes. The pattern makers broke away from the ASE due to the failures of the conservative union leadership.

From a Spark to a Blaze 1880s-1890s

By the 1880s Britain was facing intense international competition from the US and Germany. Britain was still in an important global position and still had its Empire of 370 million people. This resulted in repeated crises for capitalism leading to wages cuts, mass unemployment so the majority of the working-class were extremely insecure and destitute.

The 1880s was a new period of social upheaval and revival of socialist ideas, dormant since the Chartist movement. The Social Democratic Federation (SDF) formed in the 1880s, which focused on socialist propaganda and the unemployed, rather than the trade unions. It was from this party that a new form of militant trade unionism grew to challenge the ‘Old Gang’ of new model trade union leaders. A number left the SDF and set out to reform the old trade union movement. They met resistance from the ‘Old Guard’. This was the start of New Unionism.

The Matchmakers’ strike in 1888 against the terrible conditions the women endured, won several concessions and the Matchmakers’ Unions was formed as a result. This was followed by the 1889 Beckton Gas Works struggle for better conditions and wages, which was successful. In 1889 there was also the dockers strike for better wages that were also successful and received huge support from the trade union movement. A union was established with 30,000 members.

This New Unionism spread to other parts of Britain and into other sectors such as the Railways, Miners, and Printers. Sixty new Trade Councils were established between 1889 and 1891. The first May Day in Britain in 1890 had nearly 200,000 in attendance in Hyde Park.

The ‘Old Guard’ attempted to fight against this new threat to their authority. The 1890 TUC Congress was an open battleground between the two factions, with New Unionism coming out on top.

New Unionism was put to the test with the 1893 5-month lockout/strike in Yorkshire. The army was called in and fired on crowds, with two men dying from their injuries. The 25% wage cut that was demanded by mine owners was resisted.

The 1898 South Wales strike lasted 6 months and although not successful in the wage demands resulted in significant feelings of class solidarity and the formation of the South Wales Minters’ Federation.

Sewell describes how the new unions for the unskilled were created and also the craft unions opened up their ranks to the mass of unorganised workers. He explains that even when traditional working-class organisations are controlled by the conservatives, events can result in them being transformed into organisations of struggle.

The First Giant Step 1890s – 1900s

The Scottish Labour Party was formed in 1892 and Kier Hardie and twelve other workers won seats in the House of Commons, Hardie and two others on independent labour tickets, ten as Liberal candidates. The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was founded in Bradford in 1893. The Social Democratic Federation did not engage with this new political formation. Many militant trade unionists joined the ILP. The ILP ran 28 candidates in the 1895 elections but all were defeated. Sewell explains that the ILP weaknesses were its failure to build a mass base and its rejection of class struggle. The revolutionary socialists in the SDF, had they joined the ILP, could have pushed it to be more radical.

Sewell describes several union defeats in the early 1890s. The newly formed Gasworkers’ union was smashed by employers and the eight-hour day abolished. Shipowners in London, Cardiff and Hull enforced a series of worker lockouts. Employers also used legal means to cripple the trade unions in the 1890s, even though unions had more legal protections at this point. A general employers organisation was formed – the Employers Parliamentary Council – to agitate legal actions against unions by challenging the right of peaceful picketing and the union’s protection from liability for damages. All this showed the necessity for independent working-class political representation in the form of a party.

At the 1899 TUC Congress, a vote went in favour of independent Labour political representation. The Labour Representation Committee (LRC) (later known as the Labour Party) was founded in February 1900. Organisations in attendance were trade unions, ILP, SDF and Fabian Society. Sewell describes three tendencies that were represented at the founding conference of the Labour Party: middle-class Fabian viewpoint of Lib-Lab politics that defended class collaboration; the Kier Hardie and ILP perspective that opposed an alliance with the liberals and advocated a union-socialist federation but did not advocate socialism publicly; and the Harry Quelch and SDF position that called for a fully class conscious Socialist Party that did not collaborate with capitalism or liberals and backed class struggle.

The ILP centrist position won and the SDF left in 1901 so the other two tenancies dominated the new Labour Party. Sewell is critical of the SDF sectarian approach and argues that had they stayed they would have prevailed. Ramsey MacDonald, a liberal, joined the new party. This new party failed to ensure that it was democratically accountable to the trade unions and workers. It was a cause of celebration though as now finally the British working class had its own party and had broken the two-party system of big business.

In the 1900 election, the LCR field on 15 candidate and many trade unions were unsure to back it or not so waited. Two were elected: Kier Hardie and Richard Bell. This was quickly followed by the Taff Vale unofficial strike in South Wales. The employers fought back through the National Free Labour Association and Employers Parliamentary Council with a successful injection. The strike was settled after eleven days but the employers took their case to the House of Lords and won huge compensation. This effectively made strikes illegal undermining the union rights won in the 1870s. The employers’ legal challenge caused a huge response in the labour movement, with 100,000 joining the LCR in 1901-2 and the same amount joining in 1902-3.

At the 1906 general election, the LCR fielded 50 candidates and 29 become MPs. The Miners’ Federation instructed another 11 Lib-Lab MPs to join this group taking the total to 40 MPs. This concerned the ruling class significantly. Sewell describes how this election result was encouraged by the 1905 Russian revolution that became a rallying cause for social democracy everywhere. It was at the 1905 LCR annual conference that the party finally adopted an overtly socialist resolution. He describes how great events can have significant impacts on mass organisations and the consciousness of the working class.

The 1906 election resulted in a Liberal government. To placate the militant nature of the working class, it introduced the Trades Dispute Act (1906) to correct the legal position of trade unions. It absolved the unions of any legal responsibility for civil damages in strikes and ensured the legality of picketing. This government also introduced several reforms on pensions, unemployment and health insurance.

Sewell describes the victory of the uncompromising bold socialist Victor Grayson at the 1908 by-election in Colne Valley, Yorkshire. He was not backed by the Labour Party and once in the House of Commons, made constant interventions and was suspended several times.

The Great Unrest 1900s – 1910s

The early 20th century saw intense rivalry between the European Empires that led to the First World War. In Britain, the Liberal government reforms made little difference to inequality and a 1905 report stated that out of a population of 43 million, 38 million were categorised as poor. The cost of living steadily grew, with wages increasing very little, resulting in real wages declining.

In these conditions, strikes began to take place including the 1907 music hall strike, a seven-month engineers strike and a five-month shipwrights and joiners strike. The 1907 Belfast strike was called after demands for union recognition were refused. The strike spread to other workplaces in Belfast and the police mutinied so the army had to be called in. The docker’s strike was unsuccessful but led to the formation of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union.

Sewell describes the ruling class’s all-out offensive against organised labour. In 1909/10 there was the case of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants union vs Mr Osborne that resulted in workers having to opt-in if they wanted a portion of their wages to go to trade unions. This was followed by injunctions against 22 unions that forbid their political affiliation fees to the Labour Party. The Labour Party fought two elections in 1910 by scrapping together financial donations. In 1913 the Liberal government, under pressure from the working-class, introduced the Trade Union Act of 1913 that allowed Labour Party affiliation but included harsh restrictions on funding. It restricted general union funds being spent on political activities. They “could only come from a special political fund, which could only be set up after a successful ballot of union members.” No such restrictions were put on the Liberals on Conservatives and the funding they received from big business. This is still the situation today.

By 1910, union membership was at 2.5 million. There was growing frustration in the unions among the rank and file at the lack of progress. Syndicalist trade unionism became popular that focused on trade union strategy to change society without working through political parties and parliament.

This was the peak of Britain’s Empire as it was being challenged by Germany and the US. The ruling class started cutting back on the concessions they had given over the last 30 years especially to the top layers of the working class. The period of 1910-14 is known as the ‘Great Unrest” due to the revolutionary nature of the actions of the working class. The number of days lost of strikes increased to 10 million and union membership went from 2.5 million in 1910 to 4 million in 1914.

The first major strike was the South Wales Cambrian strike in 1910-11 in response to the owner’s reduction in wages and worsening conditions. The army was sent in and miners were killed but the strike was unsuccessful. But it did establish the demand for a minimum wage across British coalfields, resulting in a national stoppage in 1912.

Sewell describes dockworker strikes in 1911 in Southampton, Cardiff, Hull, London and Manchester. The government threatened to send troops to the London docks but huge demonstrations in support of the strike resulted in the employers negotiating with the workers.

The 1911 Liverpool general transport strike involved dockers, railway workers and sailers. The scale of the strike causes the government to send in troops and special police. Two warships were rushed to the Mersey with their guns aimed at the centre of Liverpool. A large demonstration was attacked by the police resulting in fighting and the death of two strikers. It ended with the employers giving in on the unions terms. The Dockers’ Union membership increased from 8,000 to 32,000.

There were 2 days of national rail worker strikes in 1911. The army opened fire on strikers in Liverpool and Llanelli, South Wales, killing two strikers. The unions and employers compromised resulting in union-management representation.

The 1912 national coal miners strike last 37 days and secured a minimum wage from the government. 1912 saw a huge dockers strike in London for 80,000 but was unsuccessful. The 1913 Dublin strike or lock-out involved 20,000 strikers and 300 employers with clashes between strikes and the army, resulting in several workers being killed. This led to a formation of an armed Irish Citizen’s Army to defend itself against the violence of the state and employers. There was a lot of support for the strike across Britain and Sewell describes how the TUC’s failure to widen the dispute undermined the resolve of strikers and they were starved back to work with no gains.

Sewell quotes strike data from those years: 1908, averaged 30 strikes a month; 1911, averaged 75 strikes a month; 1913-14, averaged 150 strikes a month. Sewell describes the revolutionary militancy of the labour movement and the fear of the ruling class.

Sewell describes the important contribution of syndicalism. The positive side being its rejection of class collaboration and opportunism from the union leadership, Labour Party and Liberal Party. Its strength came from its focus on industrial unionism, rank-and-file movements and rejection of ‘official’ leadership. The syndicalist ‘Miners Next Step’ was produced in 1912 in South Wales, it argued for placing industrial democracy at the centre of British working-class politics. Sewell praises the syndicalist support for class struggle and for workers to take control of factories. Sewell critiques syndicalism in that it sees unofficial action as a principle, rather than a tactic to respond to official union leadership being a barrier. He states its weakness is a lack of clear understanding of leadership and political parties to overthrow capitalism.

By 1914 there was a London building workers strike. Also in 1914, the Triple Alliance formed with 1,500,000 workers, miners, rail workers, transport unions.

Plans for Irish Home rules caused the Ulster leader to threaten mutiny and the Tory Party leader to threaten civil war. This combined with the revolutionary militancy of the labour movement meant a political crisis was close. This was avoided by the start of the First World War.

War and Revolution 1914-1918

Sewell describes the horrors of the First World War, with 10 million dead by the end and millions more disabled. He explains that the war was caused by a “build up of imperialists contradictions and tensions prior to 1914”, caused by industrial competition between Britain, Germany, France and the US and imperial conflict in Africa and the Far East between Britain, Germany, Belgium and Portugal. There was then the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary, which provided the final excuse for war. Sewell quotes the military historian Clausewitz, that war is a continuation of imperialist rivalry or geopolitics by ‘other means’ – war extends the horrors of capitalism to its extremes.

The Socialist International, with which the Labour Party was affiliated, had promised to oppose the coming war. It recognised that the war was between the different imperialist powers and that the working class in any country had nothing to gain from capitalism in peacetime or war. But instead, each national section supported its own ruling classes and it collapsed.

In response to the outbreak of war, the TUC passed a resolution to end all disputes and if difficulties arise to seriously attempt to reach settlements before further strikes. The brought the huge wave of industrial militancy to a halt. It was believed that the war would be over quickly. Sewell describes the Labour Party and trade union leadership, who either fully supported the war and conscription or those who initially opposed the war, eventually submitting to going along with it in some way. Trade union leaders agreed to ‘industrial peace’, all strikes were suspended, declared all worker organisations.

As the war continued the British soldier’s opposition to it grew, especially their resentment to the generals and their incompetence. In 1916 there was the Irish East Rising against the British government to establish an independent Irish Republic.

The government demanded increased production in engineering and shipbuilding. The owners pushed for continued relaxation of trade practices and restrictions. This resulted in worse working conditions and rights. The cost of living had gone up and unemployment increased. In response engineers in Clydeside (Glasgow) struck for a pay rise to help with rising food prices and rents, and won.

Sewell describes how trade union leaders and officials joined government and joint industrial councils to promote the war. All the unions signed a new agreement, the Treasury Agreement, that for the first time introduced industrial conscription in Britain. A new Coalition government was formed in 2015 including Liberal, Tory and Labour MPs. It brought in new draconian laws that gave the government greater powers over the munitions industry. These included authorising compulsory arbitration of disputes and the suspension of trade practices. “Munitions workers were not allowed to leave their jobs without a ‘Leaving Certificate’. Such measures introduced a virtual militarization of labour, allowing the complete subordination of the working class to the war machine.”

After the introduction of the Munitions Act, miners in South Wales rejected the wages offered by the government arbitration committee. The government responded by making strikes illegal. In response 200,000 miners went on strike, forcing the government to retreat and agree to most of their demands.

At the end of 1915, industrial action continued in Clydeside (Glasgow), with Minister of Munitions Lloyd George attending a meeting where he was shouted down. This was nationally censored in the press but a few local papers reported on it resulting in the government banning them in early 1916. The strike leaders were arrested and imprisoned. Six shop stewards were arrested and deported from Glasgow and banned from returning. By July 1916, over 1,000 workers nationally had been arrested for striking illegally and breaking the Munitions Act.

Due to the inaction of the union leaderships, shop steward committees formed around the country and joined up to form the National Shop Stewards’ and Workers’ Committee Movement. Many of its leaders were members of socialist groups and parties giving it a revolutionary focus.

In 1916, a new Coalition government formed with Lloyd George as Prime Minister. He promoted Labour MPs and trade union leaders into government posts that we responsible for the war effort and so used them to police the workers. Their authority over the workers was effectively exploited by the ruling class to hold back the growing discontent.

1917 was a peak year for strikes with over 300,000 workers in action and 2.5 million working days lost. The new rank-and-file National Shop Stewards Committee was leading strikes in Barrow, Clyde, Tyne, Coventry, London and Sheffield.

February 1917 was the first Russian Revolution. In Britain, a convention was called in Leeds to celebrate the event. It had over 1,000 delegates from the Labour Party and trade unions. The Russian Provisional Government failed to withdraw Russian from the First World War and in October 1917 the Bolshevik Party led an armed insurrection and took over the government in the second revolution of the year. The leaders, Lenin and Trotsky, issued an international appeal to end the war. This was followed by the Labour Party and TUC starting to oppose the war.

The Shop Stewards Movement in Britain was in a powerful position. TUC membership had increased from 2.25 million in 1913 to 4.5 million in 2018. Many of the unions joined together in amalgamations and federations. The Triple Alliance of miners, railway and transport workers was officially ratified, which had been put off in 1914.

There was a lot of support for the Russian revolution at the 1918 Labour Party conference in Nottingham. The Labour Party had a special conference in Westminster in 1918 where it adopted a new socialist constitution. This included the famous Clause Four : “To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.”

1918 saw a wave of unrest. There were large May Day demonstrations in the Clyde, a police strike in London, mutinies on South Coast naval bases, rail strikes, unrest in the South Wales coalfield and Lancashire cotton industry.

In November 1918, the German Revolution helped bring the First World War to an end. This was followed by revolutions in other countries in Europe such a Bavaria, Hungary and more. The European ruling classes felt seriously threatened and that the existing order was a risk. Britain plus twenty other countries sent armies to support the Russian counter-revolutionary White armies. In response protest movement in several countries appeared. Sewell describes how the British labour movement was against the attack on the Russian revolution.

In December 1918 a snap general election was held and Labour Party ran with a very radical manifesto: “Labour and the New Social Order” and called for a new society. Lloyd George’s National Coalition was returned to office was a large majority but this was not an accurate reflection of society with many soldiers yet to be demobilised and the voting registers well out of date. The Labour Party got 2.5 million votes and 57 seats in Parliament. This was a big increase from 1910 when they got 0.5 million votes.

by DGR News Service | Oct 18, 2021 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Colonialism & Conquest, Culture of Resistance, Listening to the Land, The Problem: Civilization

This is an excerpt from the book Bright Green Lies, P. 1-7

By LIERRE KEITH

“Once our authoritarian technics consolidates its powers, with the aid of its new forms of mass control, its panoply of tranquilizers and sedatives and aphrodisiacs, could democracy in any form survive? That question is absurd: Life itself will not survive, except what is funneled through the mechanical collective.”1

LEWIS MUMFORD

There is so little time and even less hope here, in the midst of ruin, at the end of the world. Every biome is in shreds. The green flesh of forests has been stripped to grim sand. The word water has been drained of meaning; the Athabascan River is essentially a planned toxic spill now, oozing from the open wound of the Alberta tar sands. When birds fly over it, they drop dead from the poison. No one believes us when we say that, but it’s true. The Appalachian Mountains are being blown to bits, their dense life of deciduous forests, including their human communities, reduced to a disposal problem called “overburden,” a word that should be considered hate speech: Living creatures—mountain laurels, wood thrush fledglings, somebody’s grandchildren—are not objects to be tossed into gullies. If there is no poetry after Auschwitz, there is no grammar after mountaintop removal. As above, so below. Coral reefs are crumbling under the acid assault of carbon. And the world’s grasslands have been sliced to ribbons, literally, with steel blades fed by fossil fuel. The hunger of those blades would be endless but for the fact that the planet is a bounded sphere: There are no continents left to eat. Every year the average American farm uses the energy equivalent of three to four tons of TNT per acre. And oil burns so easily, once every possibility for self-sustaining cultures has been destroyed. Even the memory of nature is gone, metaphrastic now, something between prehistory and a fairy tale. All that’s left is carbon, accruing into a nightmare from which dawn will not save us. Climate change slipped into climate chaos, which has become a whispered climate holocaust. At least the humans whisper. And the animals? During the 2011 Texas drought, deer abandoned their fawns for lack of milk. That is not a grief that whispers. For living beings like Labrador ducks, Javan rhinos, and Xerces blue butterflies, there is the long silence of extinction.

We have a lot of numbers. They keep us sane, providing a kind of gallows’ comfort against the intransigent sadism of power: We know the world is being murdered, despite the mass denial. The numbers are real. The numbers don’t lie. The species shrink, their extinctions swell, and all their names are other words for kin: bison, wolves, black-footed ferrets. Before me (Lierre) is the text of a talk I’ve given. The original version contains this sentence: “Another 120 species went extinct today.” The 120 is crossed clean through, with 150 written above it. But the 150 is also struck out, with 180 written above. The 180 in its turn has given way to 200. I stare at this progression with a sick sort of awe. How does my small, neat handwriting hold this horror? The numbers keep stacking up, I’m out of space in the margin, and life is running out of time.

Twelve thousand years ago, the war against the earth began. In nine places,2 people started to destroy the world by taking up agriculture. Understand what agriculture is: In blunt terms, you take a piece of land, clear every living thing off it—ultimately, down to the bacteria—and then plant it for human use. Make no mistake: Agriculture is biotic cleansing. That’s not agriculture on a bad day, or agriculture done poorly. That’s what agriculture actually is: the extirpation of living communities for a monocrop for and of humans. There were perhaps five million humans living on earth on the day this started—from this day to the ending of the world, indeed—and there are now well over seven billion. The end is written into the beginning. As earth and space sciences scholar David R. Montgomery points out, agricultural societies “last 800 to 2,000 years … until the soil gives out.”3 Fossil fuel has been a vast accelerant to both the extirpation and the monocrop—the human population has quadrupled under the swell of surplus created by the Green Revolution—but it can only be temporary. Finite quantities have a nasty habit of running out. The name for this diminishment is drawdown, and agriculture is in essence a slow bleed-out of soil, species, biomes, and ultimately the process of life itself. Vertebrate evolution has come to a halt for lack of habitat, with habitat taken by force and kept by force: Iowa alone uses the energy equivalent of 4,000 Nagasaki bombs every year. Agriculture is the original scorched-earth policy, which is why both author and permaculturist Toby Hemenway and environmental writer Richard Manning have written the same sentence: “Sustainable agriculture is an oxymoron.” To quote Manning at length: “No biologist, or anyone else for that matter, could design a system of regulations that would make agriculture sustainable. Sustainable agriculture is an oxymoron. It mostly relies on an unnatural system of annual grasses grown in a mono- culture, a system that nature does not sustain or even recognize as a natural system. We sustain it with plows, petrochemicals, fences, and subsidies, because there is no other way to sustain it.”4

Agriculture is what creates the human pattern called civilization. Civilization is not the same as culture—all humans create culture, which can be defined as the customs, beliefs, arts, cuisine, social organization, and ways of knowing and relating to each other, the land, and the divine within a specific group of people. Civilization is a specific way of life: people living in cities, with cities defined as people living in numbers large enough to require the importation of resources. What that means is that they need more than the land can give. Food, water, and energy have to come from somewhere else. From that point forward, it doesn’t matter what lovely, peaceful values people hold in their hearts. The society is dependent on imperialism and genocide because no one willingly gives up their land, their water, their trees. But since the city has used up its own, it has to go out and get those from somewhere else. That’s the last 10,000 years in a few sentences. Over and over and over, the pattern is the same. There’s a bloated power center surrounded by conquered colonies, from which the center extracts what it wants, until eventually it collapses. The conjoined horrors of militarism and slavery begin with agriculture.

Agricultural societies end up militarized—and they always do—for three reasons. First, agriculture creates a surplus, and if it can be stored, it can be stolen, so, the surplus needs to be protected. The people who do that are called soldiers. Second, the drawdown inherent in this activity means that agriculturalists will always need more land, more soil, and more resources. They need an entire class of people whose job is war, whose job is taking land and resources by force—agriculture makes that possible as well as inevitable. Third, agriculture is backbreaking labor. For anyone to have leisure, they need slaves. By the year 1800, when the fossil fuel age began, three-quarters of the people on this planet were living in conditions of slavery, indenture, or serfdom.5 Force is the only way to get and keep that many people enslaved. We’ve largely forgotten this is because we’ve been using machines—which in turn use fossil fuel—to do that work for us instead of slaves. The symbiosis of technology and culture is what historian, sociologist, and philosopher of technology Lewis Mumford (1895-1990) called a technic. A social milieu creates specific technologies which in turn shape the culture. Mumford writes, “[A] new configuration of technical invention, scientific observation, and centralized political control … gave rise to the peculiar mode of life we may now identify, without eulogy, as civilization… The new authoritarian technology was not limited by village custom or human sentiment: its herculean feats of mechanical organization rested on ruthless physical coercion, forced labor and slavery, which brought into existence machines that were capable of exerting thousands of horsepower centuries before horses were harnessed or wheels invented. This centralized technics … created complex human machines composed of specialized, standardized, replaceable, interdependent parts—the work army, the military army, the bureaucracy. These work armies and military armies raised the ceiling of human achievement: the first in mass construction, the second in mass destruction, both on a scale hitherto inconceivable.”6

Technology is anything but neutral or passive in its effects: Ploughshares require armies of slaves to operate them and soldiers to protect them. The technic that is civilization has required weapons of conquest from the beginning. “Farming spread by genocide,” Richard Manning writes.7 The destruction of Cro-Magnon Europe—the culture that bequeathed us Lascaux, a collection of cave paintings in southwestern France—took farmer-soldiers from the Near East perhaps 300 years to accomplish. The only thing exchanged between the two cultures was violence. “All these artifacts are weapons,” writes archaeologist T. Douglas Price, with his colleagues, “and there is no reason to believe that they were exchanged in a nonviolent manner.”8

Weapons are tools that civilizations will make because civilization itself is a war. Its most basic material activity is a war against the living world, and as life is destroyed, the war must spread. The spread is not just geographic, though that is both inevitable and catastrophic, turning biotic communities into gutted colonies and sovereign people into slaves. Civilization penetrates the culture as well, because the weapons are not just a technology: no tool ever is. Technologies contain the transmutational force of a technic, creating a seamless suite of social institutions and corresponding ideologies. Those ideologies will either be authoritarian or democratic, hierarchical or egalitarian. Technics are never neutral. Or, as ecopsychology pioneer Chellis Glendinning writes with spare eloquence, “All technologies are political.”9

Sources:

- Lewis Mumford, “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics,” Technology and Culture 5, no. 1 (Winter, 1964).

- There exists some debate as to how many places developed agriculture and civilizations. The best current guess seems to be nine: the Fertile Crescent; the Indian sub- continent; the Yangtze and Yellow River basins; the New Guinea Highlands; Central Mexico; Northern South America; sub-Saharan Africa; and eastern North America.

- David R. Montgomery, Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 236.

- Richard Manning, Rewilding the West: Restoration in a Prairie Landscape (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 185.

- Adam Hochschild, Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves (Boston: Mariner Books, 2006), 2.

- Mumford op cit (Winter, 1964), 3.

- Richard Manning, Against the Grain: How Agriculture Has Hijacked Civilization (New York: North Point Press, 2004), 45.

- T. Douglas Price, Anne Birgitte Gebauer, and Lawrence H. Keeley, “The Spread of Farming into Europe North of the Alps,” in Douglas T. Price and Anne Brigitte Gebauer, Last Hunters, First Farmers (Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, 1995).

- Chellis Glendinning, “Notes toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto,” Utne Reader, March- April 1990, 50.

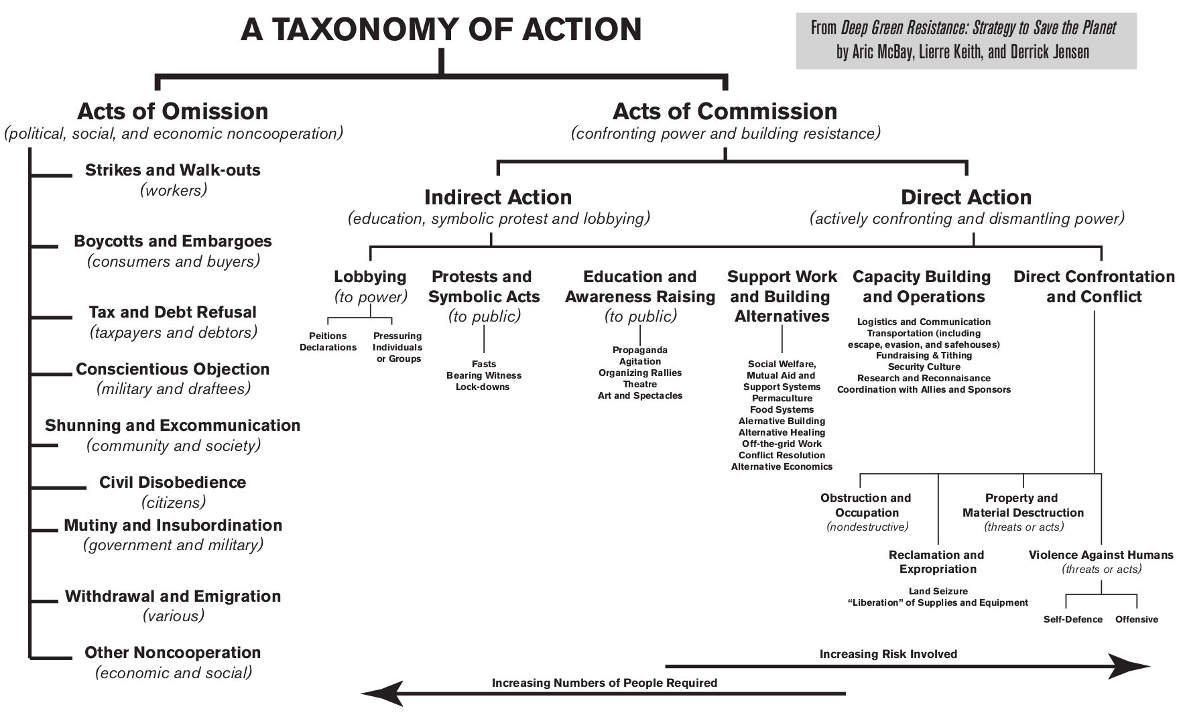

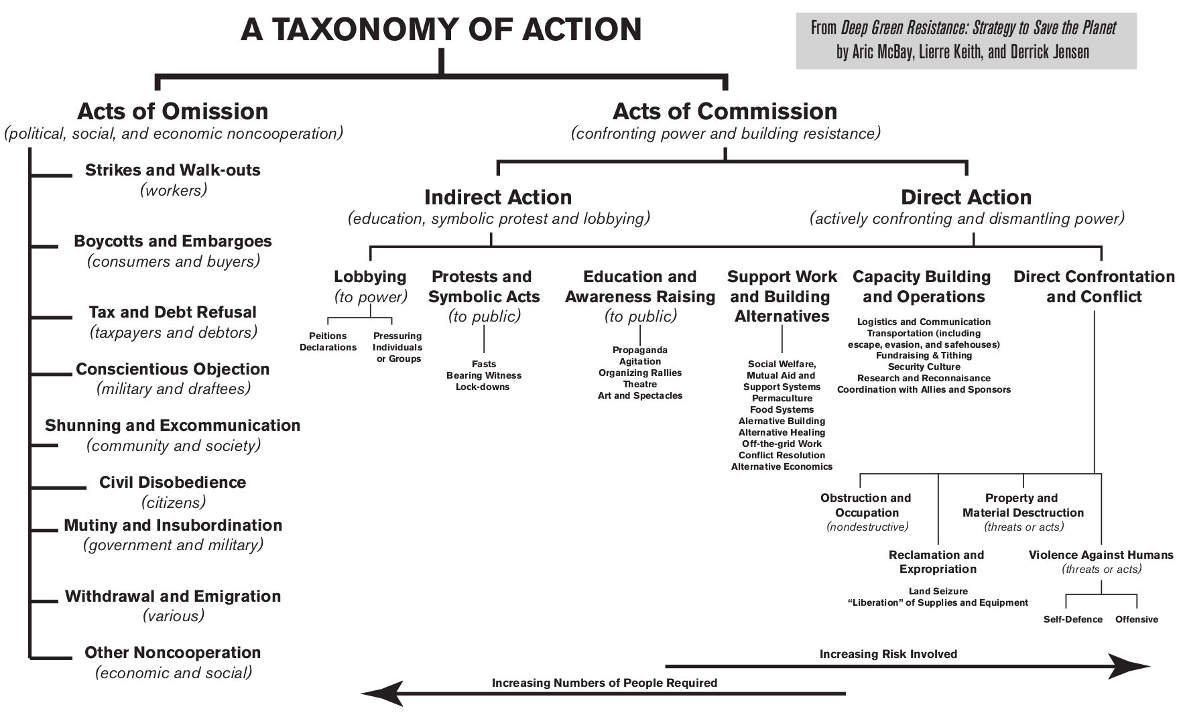

by DGR News Service | Dec 13, 2019 | Direct Action

This post is excerpted from the book, Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. Click here to buy a copy of the book or read it online. The book includes a detailed exploration of the morality of different forms of resistance, and is highly recommended reading. This is part 3 in a series. Part 1 is here, and part 2 is here.

Ultimately, success requires direct confrontation and conflict with power; you can’t win on the defensive. But direct confrontation doesn’t always mean overt confrontation. Disrupting and dismantling systems of power doesn’t require advertising who you are, when and where you are planning to act, or what means you will use.

Back in the heyday of the summit-hopping “anti-globalization” movement, I enjoyed seeing the Black Bloc in action. But I was discomfited when I saw them smash the windows of a Gap storefront, a Starbucks, or even a military recruiting office during a protest. I was not opposed to seeing those windows smashed, just surprised that those in the Black Bloc had deliberately waited until the one day their targets were surrounded by thousands of heavily armed riot police, with countless additional cameras recording their every move and dozens of police buses idling on the corner waiting to take them to jail. It seemed to be the worst possible time and place to act if their objective was to smash windows and escape to smash another day.

Of course, their real aim wasn’t to smash windows—if you wanted to destroy corporate property there are much more effective ways of doing it—but to fight. If they wanted to smash windows, they could have gone out in the middle of the night a few days before the protest and smashed every corporate franchise on the block without anyone stopping them. They wanted to fight power, and they wanted people to see them doing it. But we need to fight to win, and that means fighting smart. Sometimes that means being more covert or oblique, especially if effective resistance is going to trigger a punitive response.

That said, actions can be both effective and draw attention. Anarchist theorist and Russian revolutionary Mikhail Bakunin argued that “we must spread our principles, not with words but with deeds, for this is the most popular, the most potent, and the most irresistible form of propaganda.” The intent of the deed is not to commit a symbolic act to get attention, but to carry out a genuinely meaningful action that will serve as an example to others.

Four Methods of Direct Confrontation

There are four basic ways to directly confront those in power. Three deal with land, property, or infrastructure, and one deals specifically with human beings. They include:

- Obstruction and occupation;

- Reclamation and expropriation;

- Property and material destruction (threats or acts); and

- Violence against humans (threats or acts)

In other words, in a physical confrontation, the resistance has three main options for any (nonhuman) target: block it, take it, or break it.

Nondestructive Obstruction or Occupation

Let’s start with nondestructive obstruction or occupation—block it. This includes the blockade of a highway, a tree sit, a lockdown, or the occupation of a building. These acts prevent those in power from using or physically destroying the places in question. Provided you have enough dedicated people, these actions can be very effective.

But there are challenges. Any prolonged obstruction or occupation requires the same larger support structure as any direct action. If the target is important to those in power, they will retaliate. The more important the site, the stronger the response. In order to maintain the occupation, activists must be willing to fight off that response or suffer the consequences.

An example worth studying for many reasons is the Oka crisis of 1990. Mohawk land, including a burial ground, was taken by the town of Oka, Quebec, for—get ready—a golf course. The only deeper insult would have been a garbage dump. After months of legal protests and negotiations, the Mohawk barricaded the roads to keep the land from being destroyed. This defense of their land (“We are the pines,” one defender said) triggered a full-scale military response by the Canadian government. It also inspired acts of solidarity by other First Nations people, including a blockade of the Mercier Bridge. The bridge connects the Island of Montreal with the southern suburbs of the city—and it also runs through the Mohawk territory of Kahnawake. This was a fantastic use of a strategic resource. Enormous lines of traffic backed up, affecting the entire area for days.

At Kanehsatake, the Mohawk town near Oka, the standoff lasted a total of seventy-eight days. The police gave way to RCMP, who were then replaced by the army, complete with tanks, aircraft, and serious weapons. Every road into Oka was turned into a checkpoint. Within two weeks, there were food shortages.

Until your resistance group has participated in a siege or occupation, you may not appreciate that on top of strategy, training, and stalwart courage—a courage that the Mohawk have displayed for hundreds of years—you need basic supplies and a plan for getting more. If an army marches on its stomach, an occupation lasts as long as its stores. Getting food and supplies into Kanehsatake and then to the people behind the barricades was a constant struggle for the support workers, and gave the police and army plenty of opportunity to harass and humiliate resisters. With the whole world watching, the government couldn’t starve the Mohawk outright, but few indigenous groups engaged in land struggles are lucky enough to garner that level of media interest. Food wasn’t hard to collect: the Quebec Native Women’s Association started a food depot and donations poured in. But the supplies had to be arduously hauled through the woods to circumvent the checkpoints. Trucks of food were kept waiting for hours only to be turned away.31 Women were subjected to strip searches by male soldiers. At least one Mohawk man had a burning cigarette put out on his stomach, then dropped down the front of his pants.32 Human rights observers were harassed by both the police and by angry white mobs.33

The overwhelming threat of force eventually got the blockade on the bridge removed. At Kanehsatake, the army pushed the defenders to one building. Inside, thirteen men, sixteen women, and six children tried to withstand the weight of the Canadian military. No amount of spiritual strength or committed courage could have prevailed.

The siege ended when the defenders decided to disengage. In their history of the crisis, People of the Pines, Geoffrey York and Loreen Pindera write, “Their negotiating prospects were bleak, they were isolated and powerless, and their living conditions were increasingly stressful . . . tempers were flaring and arguments were breaking out. The psychological warfare and the constant noise of military helicopters had worn down their resistance.”34 Without the presence of the media, they could have been raped, hacked to pieces, gunned down, or incinerated to ash, things that routinely happen to indigenous people who fight back. The film Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance documents how viciously they were treated when the military found the retreating group on the road.

One reason small guerilla groups are so effective against larger and better-equipped armies is because they can use their secrecy and mobility to choose when, where, and under what circumstances they fight their enemy. They only engage in it when they reasonably expect to win, and avoid combat the rest of the time. But by engaging in the tactic of obstruction or occupation a resistance group gives up mobility, allowing the enemy to attack when it is favorable to them and giving up the very thing that makes small guerilla groups so effective.

The people at Kanehsatake had no choice but to give up that mobility. They had to defend their land which was under imminent threat. The end was written into the beginning; even 1,000 well-armed warriors could not have held off the Canadian armed forces. The Mohawk should not have been in a position where they had no choice, and the blame here belongs to the white people who claim to be their allies. Why does the defense of the land always fall to the indigenous people? Why do we, with our privileges and resources, leave the dirty and dangerous work of real resistance to the poor and embattled? Some white people did step up, from international observers to local church folks. But the support needs to be overwhelming and it needs to come before a doomed battle is the only option. A Mohawk burial ground should never have been threatened with a golf course. Enough white people standing behind the legal efforts would have stopped this before it escalated into razor wire and strip searches. Oka was ultimately a failure of systematic solidarity.

Reclamation and Expropriation

The second means of direct conflict is reclamation and expropriation—take it. Instead of blocking the use of land or property, the resistance takes it for their own use. For example, the Landless Workers Movement—centered in Brazil, a country renowned for unjust land distribution—occupies “underused” rural farmland (typically owned by wealthy absentee landlords) and sets up farming villages for landless or displaced people. Thanks to a land reform clause in the Brazilian constitution, the occupiers have been able to compel the government to expropriate the land and give them title. The movement has also engaged in direct action like blockades, and has set up its own education and literacy programs, as well as sustainable agriculture initiatives. The Landless Workers Movement is considered the largest social movement in Latin America, with an estimated 1.5 million members.

Expropriation has been a common tactic in various stages of revolution. “Loot the looters!” proclaimed the Bolsheviks during Russia’s October Revolution. Early on, the Bolsheviks staged bank robberies to acquire funds for their cause. Successful revolutionaries, as well as mainstream leftists, have also engaged in more “legitimate” activities, but these are no less likely to trigger reprisals. When the democratically elected government of Iran nationalized an oil company in 1953, the CIA responded by staging a coup. And, of course, guerilla movements commonly “liberate” equipment from occupiers in order to carry out their own activities.

Property and Material Destruction

The third means of direct conflict is property and material destruction—break it. This category includes sabotage. Some say the word sabotage comes from early Luddites tossing wooden shoes (sabots) into machinery, stopping the gears. But the term probably comes from a 1910 French railway strike, when workers destroyed the wooden shoes holding the rails—a good example of moving up the infrastructure. And sabotage can be more than just physical damage to machines; labor activism has long included work slowdowns and deliberate bungling.

Sabotage is an essential part of war and resistance to occupation. This is widely recognized by armed forces, and the US military has published a number of manuals and pamphlets on sabotage for use by occupied people. The Simple Sabotage Field Manual published by the Office of Strategic Services during World War II offers suggestions on how to deploy and motivate saboteurs, and specific means that can be used. “Simple sabotage is more than malicious mischief,” it warns, “and it should always consist of acts whose results will be detrimental to the materials and manpower of the enemy.” It warns that a saboteur should never attack targets beyond his or her capacity, and should try to damage materials in use, or destined for use, by the enemy. “It will be safe for him to assume that almost any product of heavy industry is destined for enemy use, and that the most efficient fuels and lubricants also are destined for enemy use.” It encourages the saboteur to target transportation and communications systems and devices in particular, as well as other critical materials for the functioning of those systems and of the broader occupational apparatus. Its particular instructions range from burning enemy infrastructure to blocking toilets and jamming locks, from working slowly or inefficiently in factories to damaging work tools through deliberate negligence, from spreading false rumors or misleading information to the occupiers to engaging in long and inefficient workplace meetings.

Ever since the industrial revolution, targeting infrastructure has been a highly effective means of engaging in conflict. It may be surprising to some that the end of the American Civil War was brought about in large part by attacks on infrastructure. From its onset in 1861, the Civil War was extremely bloody, killing more American combatants than all other wars before or since, combined. After several years of this, President Lincoln and his chief generals agreed to move from a “limited war” to a “total war” in an attempt to decisively end the war and bring about victory.

Historian Bruce Catton described the 1864 shift, when Union general “[William Tecumseh] Sherman led his army deep into the Confederate heartland of Georgia and South Carolina, destroying their economic infrastructures.” Catton writes that “it was also the nineteenth-century equivalent of the modern bombing raid, a blow at the civilian underpinning of the military machine. Bridges, railroads, machine shops, warehouses—anything of this nature that lay in Sherman’s path was burned or dismantled.” Telegraph lines were targeted as well, but so was the agricultural base. The Union Army selectively burned barns, mills, and cotton gins, and occasionally burned crops or captured livestock. This was partly an attack on agriculture-based slavery, and partly a way of provisioning the Union Army while undermining the Confederates. These attacks did take place with a specific code of conduct, and General Sherman ordered his men to distinguish “between the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor or industrious, usually neutral or friendly.”

Catton argues that military engagements were “incidental” to the overall goal of striking the infrastructure, a goal which was successfully carried out. As historian David J. Eicher wrote, “Sherman had accomplished an amazing task. He had defied military principles by operating deep within enemy territory and without lines of supply or communication. He destroyed much of the South’s potential and psychology to wage war.” The strategy was crucial to the northern victory.

Violence Against Humans