by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 15, 2018 | Alienation & Mental Health

Featured image: JD Lasica, Flickr, c.c. 2.0

by Steven Gorelick / Local Futures

Tucked within the pages of the January issue of the Agriview, a monthly farm publication published by the State of Vermont, was a short survey from the Department of Public Service (DPS). Described as an aid to the Department in drafting their “Ten Year Telecom Plan”, the survey contains eight questions, the first seven of which are simple multiple-choice queries about current internet and cell phone service at the respondent’s farm. The final question is the one that caught my eye:

“In what ways could your agriculture business be improved with better access to cell signal or higher speed internet service?”

Two things are immediately revealed by this question:

(a) The DPS believes that the only possible outcome from faster and better telecommunication access is that things will be “improved.”

(b) If you disagree with the DPS on point (a), they don’t want to hear about it.

A cynic might conclude that the DPS is only looking for survey results that justify decisions they’ve already made, and that’s probably true. But the department’s upbeat, one-dimensional outlook on technological change is actually the accepted norm in America. In his book In the Absence of the Sacred, Jerry Mander points out that new technologies are usually introduced through “best-case scenarios”: “The first waves of description are invariably optimistic, even utopian. This is because in capitalist societies early descriptions of new technologies come from their inventors and the people who stand to gain from their acceptance.” [1]

Silicon Valley entrepreneurs have made an art of utopian hype. Microsoft founder Bill Gates, one of high-tech’s most influential boosters, gave us such platitudes as “personal computers have become the most empowering tool we’ve ever created,”[2] and my favorite, “technology is unlocking the innate compassion we have for our fellow human beings.”[3]Other prognosticators include Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who informs us that social media is “making the world more transparent” and “giving everyone a voice.” Needless to say, Gates, Zuckerberg and many others have become billionaires thanks to the public’s embrace of the technologies they touted.

The DPS survey reveals another shortcoming in how we look at technology: we tend to evaluate technologies solely in terms of their usefulness to us personally. Jerry Mander put it this way: “When we use a computer we don’t ask if computer technology makes nuclear annihilation more or less possible, or if corporate power is increased or decreased thereby. While watching television, we don’t think about the impact upon the tens of millions of people around the world who are absorbing the same images at the same time, nor about how TV homogenizes minds and cultures… If we have criticisms of technology they are usually confined to details of personal dissatisfaction.”

The DPS survey demonstrates this narrow focus: it only asks how faster telecommunications will affect the respondent’s “agriculture business”, while broader impacts – on family and community, on society as a whole and on the natural world – are out of bounds. A narrow focus is especially problematic when it comes to digital technologies, because the benefits they offer us as individuals – ultra-fast communication, the ability to access entertainment and information from all over the world – are so obvious that they can blind us to broader and longer-term impacts.

Recently, though – despite decades of hype and a continuing barrage of advertising –cracks are beginning to appear in the pro-digital consensus. The illusion that technology “unlocks compassion for our fellow human beings” has become harder to maintain in the face of what we now know: digital technologies are the basis for smart bombs, drone warfare and autonomous weaponry; they enable governments to conduct surveillance on virtually everyone, and allow corporations to gather and sell information about our habits and behavior; they permit online retailers to destroy brick-and-mortar businesses that are integral to healthy local economies.

We’ve also learned that social media doesn’t just enable us to connect with family and friends, it also provides a powerful recruitment tool for extremist groups – from neo-Nazis and white supremacists to ISIS. And all but the most die-hard Trump supporters acknowledge that social media was used to disrupt the democratic process in 2016, and that it is effectively used by authoritarian political leaders all over the world – including Mr. Trump – to spread false information and “alternative facts.”

People are even beginning to see that social media is not all that “empowering” for the individual. We recognize the addictive nature of internet use, though most of us don’t yet take it seriously: a friend will say, “I’m totally addicted to Facebook!” and we’ll just laugh. But it’s not a laughing matter: according to The American Journal of Psychiatry, “Internet addiction is resistant to treatment, entails significant risks, and has high relapse rates.”[4]The risks are highest among the young: a study of 14-24 year-olds in the UK found that social media “exacerbate children’s and young people’s body image worries, and worsen bullying, sleep problems and feelings of anxiety, depression and loneliness.”[5] Not surprisingly, a 2017 study in the US found that the suicide rate among teenagers has risen in tandem with their ownership of smartphones.[6]

Little of this should have been surprising within the digital design world. Facebook’s founding president, Sean Parker, now admits that the company knew from the start that they were creating an addictive product, one aimed at “exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.” [7] Nir Eyal, corporate consultant and author of Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, acknowledges that “the technologies we use have turned into compulsions, if not full-fledged addictions… just as their designers intended.”[8]

These addictions have serious consequences not just for the individual, but for society as a whole: “The short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works. No civil discourse, no cooperation, misinformation, mistruth.” This is not the opinion of some left-leaning Luddite, but Facebook’s former vice-president for user growth, Chamath Palihapitiya.[9]

Digital technologies are a threat to democracy in ways that go deeper than even Vladimir Putin might hope. According to former Google strategist James Williams, “The dynamics of the attention economy are structurally set up to undermine the human will. If politics is an expression of our human will… then the attention economy is directly undermining the assumptions that democracy rests on.”[10]

There is also evidence that a child’s use of computers negatively affects their neurological development.[11] Tech insiders like Sean Parker may not know for certain “what it’s doing to our children’s brains,” but Parker isn’t taking any chances: “I can control my kids’ decisions, which is that they’re not allowed to use that shit.”[12] Lots of other Silicon Valley technologists are keeping their children away from screens, in part by sending them to private schools that prohibit the use of smartphones, tablets and laptops.[13] Meanwhile, the companies they work for continue to push their addictive products onto children worldwide: Alphabet, Google’s parent corporation, provides “free” tablets to public elementary schools, while Facebook recently launched a new app called Messenger Kids – aimed specifically at pre-teens.[14]

Much of the “best case scenario” for digital technology rests on its supposed environmental benefits (remember the “paperless society”?) But illusions about “clean” technology are dissolving in the horrific toxic wasteland of Boatou, China, where rare earth metals – needed for almost all digital devices – are mined and processed.[15] Another dirty secret is the cumulative energy demand of all these technologies: it’s estimated that within the next couple of years, internet-connected devices will consume more energy than aviation and shipping; by 2040 they will account for 14% of global greenhouse gas emissions – about the same proportion as the United States today.[16]

What does all this mean for ordinary citizens? For one, we need to begin looking beyond the immediate convenience that technologies offer us as individuals, and consider their broader impacts on community, society and nature. We should remain highly skeptical about the utopian claims of those who stand to profit from new technologies. And, perhaps most importantly, we need to allow our own children to grow up – as long as possible – in nature and community, rather than in a corporate-mediated technosphere of digital screens. Doing so will require us to challenge school boards and administrators who have been sold on the idea that putting elementary school children in front of screens is the best way to “prepare them for the future.”

As for the Department of Public Service, my survey response will say that the costs of improved telecom access would far outweigh the benefits. It would be of no consequence to my farm business, which by design only involves direct sales to nearby shops and individuals. More importantly, our farm is not only an “agriculture business” it is also our home, and that’s where the impact would be greatest. Better digital access would make it easier for me and members of my family to engage in addictive behavior, from online gambling and pornography to compulsive shopping, video games and internet “connectivity” itself. It would consume the attention of my children, leaving them more vulnerable to insecurity and depression, while displacing time better spent in nature or in face-to-face encounters with friends and neighbors. There are broader impacts as well: we would be increasingly tempted to buy our needs online, thus hurting local businesses and draining money out of our local economy. And almost everything we might do online would add a further increment to the growing wealth and influence of a handful of corporations – Amazon, Google, Facebook, Apple, and others – that are already among the most powerful in the world.

These are significant impacts. But the DPS doesn’t want to hear about them.

Notes

[1] Mander, Jerry (1991) In the Absence of the Sacred, Sierra Club: San Francisco.

[2] Speech at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Feb. 24, 2004.

[3] “Bill Gates: Here’s my plan to improve our world – and how you can help”, Wired magazine, November 12, 2013

[4] Konnikova, Maria, “Is Internet Addiction a Real Thing?” The New Yorker, November 26, 2014.

[5] Campbell, Dennis, “Facebook and Twitter ‘harm young people’s mental health’”, The Guardian, May 19, 2017.

[6] “Teen suicide rate suddenly rises with heavy use of smartphones, social media,” Washington Times, Nov. 14, 2017.

[7] Solon, Olivia, “Ex-Facebook president Sean Parker: site made to exploit human ‘vulnerability’”, The Guardian, November 9, 2017.

[8] Lewis, Paul, “’Our minds can be hijacked’: the tech insiders who fear a smartphone dystopia”, The Guardian, October 6, 2017.

[9] Wong, Julia Carrie, “Former Facebook executive: social media is ripping society apart”, The Guardian, December 12, 2017

[10] Lewis, P. op. cit.

[11] Carr, Nicholas (2010) The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, W.W. Norton.

[12] Wong, Julia Carrie, op. cit.

[13] Lewis, P. op. cit.

[14] Kircher, Madison Malone, “Facebook Releases App for Kids Under 13. What Could Possibly Go Wrong Here?” New York Magazine, December 4, 2017.

[15] Maughan, Tim, “The dystopian lake filled by the world’s tech lust”, BBC Future, April 2, 2015.

[16] “’Tsunami of data’ could consume one-fifth of global electricity by 2025”, The Guardian, December 11, 2017.

by DGR News Service | Jun 21, 2014 | Gender, Repression at Home

By Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

Despite the seeming popularity of environmental and social justice work in the modern world, we’re not winning. We’re losing. In fact, we’re losing really badly. [1]

Why is that?

One reason is because few popular strategies pose real threats to power. That’s not an accident: the rules of social change have been clearly defined by those in power. Either you play by the rules — rules which don’t allow you to win — or you break free of the rules, and face the consequences.

Play By The Rules, or Raise the Stakes

We all know the rules: you’re allowed to vote for either one capitalist or the other, vote with your dollars,[2] write petitions (you really should sign this one), you can shop at local businesses, you can eat organic food (if you can afford it), and you can do all kinds of great things!

But if you step outside the box of acceptable activism, you’re asking for trouble. At best, you’ll face ridicule and scorn. But the real heat is reserved for movements that pose real threats. Whether broad-based people’s movements like Occupy or more focused revolutionary threats like the Black Panthers, threats to power break the most important rule they want us to follow: never fight back.

State Tactic #1: Overt Repression

Fighting back – indeed, any real resistance – is sacrilegious to those in power. Their response is often straightforward: a dozen cops slam you to the ground and cuff you; “less-lethal” weapons cover the advance of a line of riot police; the sharp report of SWAT team’s bullets.

This type of overt repression is brutally effective. When faced with jail, serious injury, or even death, most don’t have the courage and the strategy to go on. As we have seen, state violence can behead a movement.

That was the case with Fred Hampton, an up-and-coming Black Panther Party leader in Chicago, Illinois. A talented organizer, Hampton made significant gains for the Panthers in Chicago, working to end violence between rival (mostly black) gangs and building revolutionary alliances with groups like the Young Lords, Students for A Democratic Society, and the Brown Berets. He also contributed to community education work and to the Panther’s free breakfast program.

These activities could not be tolerated by those in power: they knew that a charismatic, strategic thinker like Hampton could be the nucleus of revolution. So, they decided to murder him. On December 4, 1969, an FBI snitch slipped Hampton a sedative. Chicago police and FBI agents entered his home, shot and killed the guard, Mark Clark, and entered Hampton’s room. The cops fired two shots directly into his head as he lay unconscious. He was 21 years old.

The Occupy Movement, at its height, posed a threat to power by making the realities of mass anti-capitalism and discontent visible, and by providing physical focal points for the dissent that spawns revolution. While Occupy had some issues (such as the difficulties of consensus decision-making and generally poor responses to abusive behavior inside camps), the movement was dynamic. It claimed physical space for the messy work of revolution to happen, and represented the locus of a true threat.

The response was predictable: the media assaulted relentlessly, businesses led efforts to change local laws and outlaw encampments, and riot police were called in as the knockout punch. It was a devastating flurry of blows, and the movement hasn’t yet recovered. (Although many of the lessons learned at Occupy may serve us well in the coming years).

State Tactic #2: Covert Repression

Violent repression is glaring. It gets covered in the news, and you can see it on the streets. But other times, repression isn’t so obvious. A recent leaked document from the private security and corporate intelligence firm Strategic Forecasting, Inc. (better known as STRATFOR) contained this illustrative statement:

Most authorities will tolerate a certain amount of activism because it is seen as a way to let off steam. They appease the protesters by letting them think that they are making a difference — as long as the protesters do not pose a threat. But as protest movements grow, authorities will act more aggressively to neutralize the organizers.

The key word is neutralize: it represents a more sophisticated strategy on behalf of power, a set of tactics more insidious than brute force.

Most of us have probably heard about COINTELPRO (shorthand for Counter-Intelligence Program), a covert FBI program officially underway between 1956 and 1971. COINTELPRO mainly targeted socialists and communists, black nationalists, Civil Rights groups, the American Indian Movement, and much of the left, from Quakers to Weathermen. The FBI used four main techniques to undermine, discredit, eliminate, and otherwise neutralize these threats:

- Force

- Harassment (subpoenas, false accusations, discriminatory enforcement of taxation, etc.)

- Infiltration

- Psychological warfare

How can we become resilient to these threats? Perhaps the first step is to understand them; to internalize the consequences of the tactics being used against us.

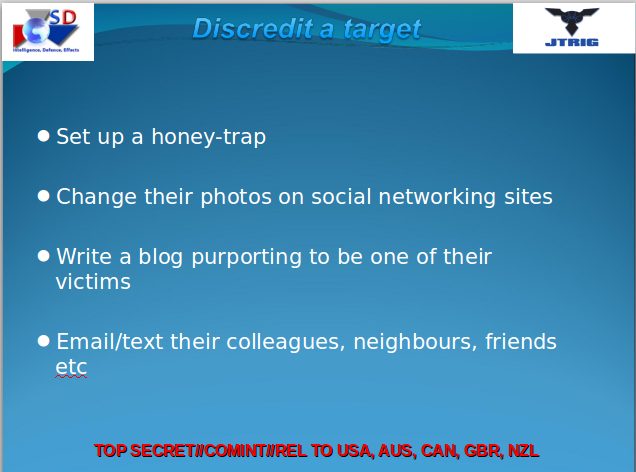

The JTRIG Leaks

On February 24 of this year, Glenn Greenwald released an article detailing a secret National Security Agency (NSA) unit called JTRIG (Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group). The article, which sheds new light on the tactics used to suppress social movements and threats to power, is worth quoting at length:

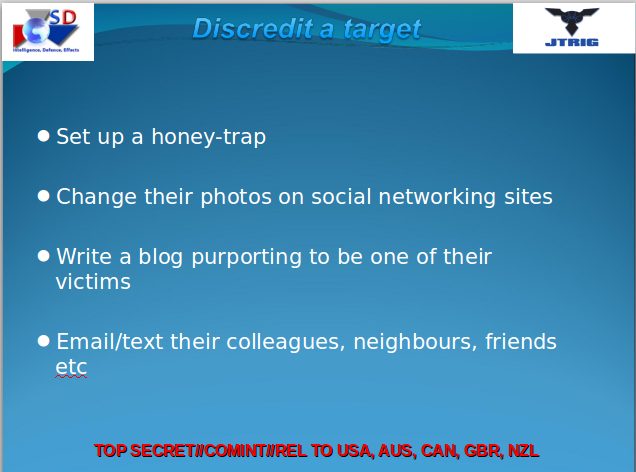

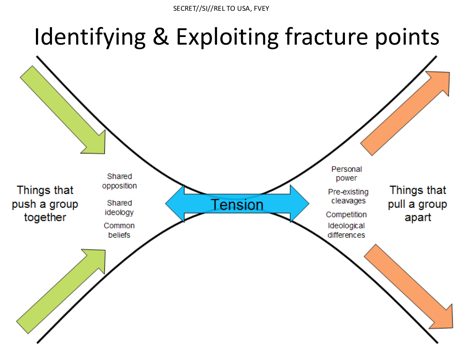

Among the core self-identified purposes of JTRIG are two tactics: (1) to inject all sorts of false material onto the internet in order to destroy the reputation of its targets; and (2) to use social sciences and other techniques to manipulate online discourse and activism to generate outcomes it considers desirable. To see how extremist these programs are, just consider the tactics they boast of using to achieve those ends: “false flag operations” (posting material to the internet and falsely attributing it to someone else), fake victim blog posts (pretending to be a victim of the individual whose reputation they want to destroy), and posting “negative information” on various forums.

It shouldn’t come as a total surprise that those in power use lies, manipulation, false information, fake identities, and “manipulation [of] online discourse” to further their ends. They always fight dirty; it’s what they do. They never fight fair, they can never allow truth to be shown, because to do so would expose their own weakness.

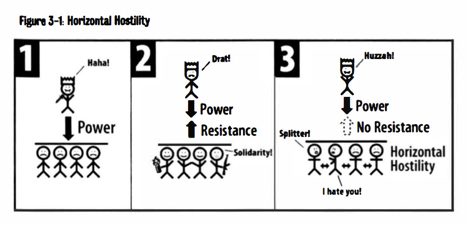

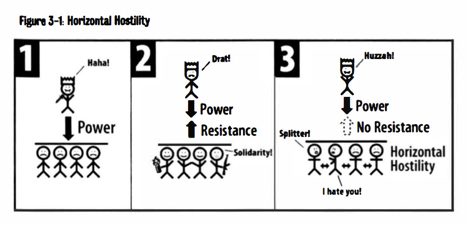

As shown by COINTELPRO, this type of operation is highly effective at neutralizing threats. Snitchjacketing and divisive movement tactics were used widely during the COINTELPRO era, and encouraged activists to break ties, create rivalries, and vie against one another. In many cases, it even led to violence: prominent, good hearted activists would be labeled “snitches” by agents, and would be isolated, shunned, and even killed.

As a friend put it,

“By encouraging horizontal, crowdsourced repression, activists’ focus is shifted safely away from those in power and towards each other.”

Are Activists Targeted?

Some organizations have ideas so revolutionary, so incendiary that they pose a threat all by themselves, simply by existing.

Deep Green Resistance is such a group. If these tactics are being used to neutralize activist groups, then Deep Green Resistance (DGR) seems a prime target. Proudly Luddite in character, DGR believes that the industrial way of life, the soil-destroying process known as agriculture, and the social system called civilization are literally killing the planet – at the rate of 200 species extinctions, 30 million trees, and 100 million tons of CO2 every day. With numbers like that, time is short.

With two key pieces of knowledge, the DGR strategy comes into focus. The first is that global industrial civilization will inevitably collapse under the weight of its own destructiveness. The second is that this collapse isn’t coming soon enough: life on Earth could very well be doomed by the time this collapse stops the accelerating destruction.

With these understandings, DGR advocates for a strategy to pro-actively dismantle industrial civilization. The strategy (which acknowledges that resisters will face fierce opposition from governments, corporations, and those who cling to modern life) calls for direct attacks on critical infrastructure – electric grids, fossil fuel networks, communications, etc. – with one goal: to shut down the global industrial economy. Permanently.

The strategy of direct attacks on infrastructure has been used in countless wars, uprisings, and conflicts because it is extremely effective. The same strategies are taught at military schools and training camps around the planet, and it is for this reason – an effective strategy – that DGR poses a real and serious threat to power. Of course, writing openly about such activities and then taking part in them would be stupid, which is why DGR is an “aboveground” organization. Our work is limited to building a culture of resistance (which is no easy feat: our work spans the range of activities from non-violent resistance to educational campaigns, community organizing, and building alternative systems) and spreading the strategies that we advocate in the hope that clandestine networks can pull off the dirty work in secret.

When I speak to veterans – hard-jawed ex-special forces guys – they say the strategy is good. It’s a real threat.

Threat Met With Backlash

That threat has not gone unanswered. In a somewhat unsurprising twist, given the information we’ve gone over already, DGR’s greatest challenges have not come from the government, at least not overtly. Instead, the biggest challenges have come from radical environmentalists and social justice activists: from those we would expect to be among our supporters and allies. The focal point of the controversy? Gender.

The conflict has a long history and deserves a few hours of discussion and reading, but here is the short version: DGR holds that female-only spaces should be reserved for females. This offends many who believe that male-born individuals (who later come to identify as female) should be allowed access to these spaces. It’s all part of a broader, ongoing disagreement between gender abolitionists (like DGR and others), who see gender as the cultural lattice of women’s oppression, and those who view gender as an identity that is beyond criticism.

(To learn more about the conflict, view Rachel Ivey’s presentation entitled The End of Gender.)

Due to this position, our organization has been blacklisted from speaking at various venues, our organizers have received threats of violence (often sexualized), and our participation in a number of struggles has been blocked – at the expense of the cause at hand.

A Case Study in JTRIG?

Much of the anti-DGR rhetoric has been extraordinary, not for passionate political disagreement, but for misinformation and what appears to be COINTELPRO-style divisiveness. Are we the victims of a JTRIG-style smear campaign?

On February 23 of this year, the Earth First! Newswire released an anonymous article attacking Deep Green Resistance. The main subject of the article was the ongoing debate over gender issues.

(Although perhaps debate is the wrong word in this case: Earth First! Newswire has published half a dozen vitriolic pieces attacking DGR. They seem to have an obsession. On the other hand, DGR has never used organizational resources or platforms to publish a negative comment about Earth First.)

Here are a few of the fabrications contained in the February 23 article:

- “Keith and Jensen [DGR co-founders] do not recognize the validity of traditionally marginalized struggles [like] Black Power.” (a wild, false claim, given the long and public history of anti-racist work and solidarity by those two. [3])

- DGR members have “outed” transgender people by posting naked photos of them. (Completely false not to mention obscene and offensive.[4])

- DGR is “allied with” gay-to-straight conversion camps. (The lies get ever more absurd. DGR has countless lesbian and gay members, including founding members. Lesbian and gay members are involved at every level of decision making in DGR.)

- DGR requires “genital checks” for new members. (I can’t believe we even have to address this – it’s a surreal accusation. It is, of course, a lie.)

If these claims weren’t so serious, they would be laughable. But lies like this are no laughing matter.

Here is one illustrative list of tactics from the JTRIG leaks:

“Crowdsourced Repression”

The timing of these events – the Earth First! Newswire article followed the very next day by Greenwald’s JTRIG article – is ironic. Of course, it made me think: are we the victims of a JTRIG-style character assassination? Or am I drawing conclusions where there are none to be drawn?

The campaigns against DGR do have many of the hallmarks of COINTELPRO-style repression. They are built on a foundation of political differences magnified into divisive hatred through paranoia and the spread of hearsay. In the 1960s and 70s, techniques that seem similar were used to create divisions within groups like the Black Panthers and the American Indian Movement.

Ultimately, these movements tore themselves apart in violence and suspicion; the powerful were laughing all the way to the bank. In many cases, we don’t even know if the FBI was involved; what is certain is that the FBI-style tactics – snitchjacketing, rumormongering, the sowing of division and hatred – were being adopted by paranoid activists.

In some ways, the truth doesn’t really matter. Whether these activists were working for the state or not, they served to destroy movements, alliances, and friendships that took decades or generations to build.

I’ll be clear: I don’t mean to claim that the “Letter Collective” (as the anonymous authors of the February 23 article named themselves) are agents of the state. To do so would be a violation of security culture. [5] Modern activists seem to have largely forgotten the lessons of COINTELPRO, and I am wary of forgetting those lessons myself. Snitchjacketing is a bad behavior, and we should have no tolerance for it unless there is substantive evidence.

But members of the “Letter Collective”, at the very least, have violated security culture by spreading rumors and unsubstantiated claims of serious misconduct. Good security culture practices preclude this behavior. In the face of JTRIG and the modern surveillance and repression state, careful validation of serious claims is the least that activists can do. Didn’t we learn this lesson in the 60s?

Divide and Conquer

By itself, verifying rumors before spreading them is a poor defense against the repression modern activists face. Instead, we must challenge divisiveness itself: one of the biggest threats to our success.

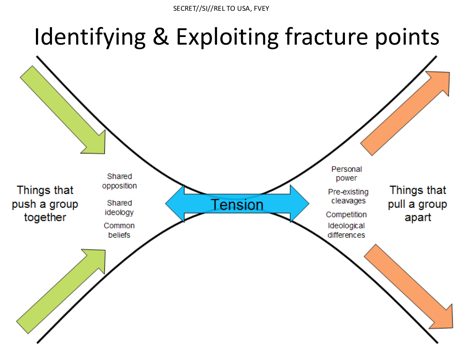

The 2011 STRATFOR leak included information about corporate strategies to neutralize activist and community movements. Essentially, STRATFOR advocates dividing movements into four character types: radicals, idealists, realists, and opportunists. These camps can then be dealt with summarily:

First, isolate the radicals. Second, “cultivate” the idealists and “educate” them into becoming realists. And finally, co-opt the realists into agreeing with industry. [6]

This is how movements are neutralized: those who should be allies are divided, infighting becomes rampant, and paranoia rules the roost. To combat these strategies, we must understand the danger they represent and how to counter them.

Fight Repression With Solidarity

We all want to win. We want to end capitalism, reverse ecological collapse, and build a culture in which social justice is fundamental. Many of us have different specific goals or strategies, but we must find similarities, overlaps, and areas where we can work together.

As Bob Ages, commenting on STRATFOR’s divide-and-conquer tactics, put it in a recent piece:

“Our response has to be the opposite; bridging divides, foster mutual understanding and solidarity, stand together come hell or high water.”

Many people across the left share 80% or more of their politics, and yet constructive criticism and mature discussion of disagreements is the exception, not the rule. We need more thoughtful behavior. Don’t spread rumors, don’t tear down other activists, and don’t forget who the real enemy is. Don’t waste your time fighting those who should be your allies – even if they are only partial allies. Let’s disagree, and let our disagreements help us learn more from each other and build alliances.

In the end, that’s our only chance of winning: together.

References

Max Wilbert lives in the Pacific Northwest, where he works to support indigenous resistance to industrial extraction projects, anti-racist initiatives, and radical feminist struggles as part of Deep Green Resistance. He makes his living as a writer and photographer, and can be contacted at max@maxwilbert.org.

From Dissident Voice

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Dec 19, 2012 | Property & Material Destruction

Wherever there has been oppression, there has been resistance.

Despite the narratives that are drilled and forced into our heads—narratives of the exceptionality and futility of resistance—the history of civilization is chalk full of individuals, groups, movements that stood in the face of subjugation and cruelty to fight for a better world.

This is as true now as it has ever been, whether we’re talking about underground and aboveground groups finding indirect ways to collaborate in defending Russian forests, Ogoni militants attacking pipelines in the Niger Delta, farmers in North Dakota toppling interstate electrical transmission lines, Norwegians sinking whaling ships, Saudi Arabians using computer viruses to attack the world’s largest oil company, Germans sabotaging sport hunting, bombings of nanotechnology labs in Mexico, or road occupations defending forests in Borneo. From the Luddites to the Naxalites, militant action against ecocide has a proud history and is nothing new.

Beyond these—the organizations and groups whose names we know—are an untold number of actions and actors, working on their own or in small groups to strike blows (however small) against the industrial machine. They often receive no recognition, their names and deeds don’t make the news and the glued locks on the slaughterhouse door or slashed tires on the logging truck are attributed to apolitical and trouble-making adolescents.

But they continue—the faceless and the nameless, the mysterious who help to make sure that this war has two sides. Every year, hundreds of brave individuals enact their convictions: thousands of animals are freed from captivity & torture, locks are glued, equipment and vehicles torched, roads torn up, trees spiked, hunting lodges & towers sabotaged, cell phone towers destroyed, and more.

Militant action against the horror of civilization isn’t a mystical idea or lofty concept. Too often, it is made to seem something entirely unreal, impossibly distant from the world we actually live in. It is made out to be the work of mythical figures or shadowy organizations, compared to whom we are nothing of note. Real resistance is something that happens ‘out there’, far away from anything resembling our own lives.

But this is entirely untrue.

While the particular motives and passions of individual actionists inevitably vary, there are no superheroes, just those ordinary people who have moved beyond fear and into action. Similarly, no one is born knowing how to wire explosives or sabotage a train, but that hasn’t stopped pipelines from exploding or trains from being shut off. Despite what the dominant narratives tell us, it is not exceptional or unusual to fight back against brutality.

Tangible acts of resistance take place every day, building on one another slowly gradually. In the last year, there have been at least several hundred actions, and those are just the ones that were reported on websites like ‘Bite Back’ or DGR’s new Underground Action Calendar. And such action is nothing new either; quiet acts of sabotage against development and infrastructure projects—be they dams or railways—are forms of resistance that go back generations; resistance that persists through the silence and the years. Though these individual actions may not be much in and of themselves, they are not alone.

They are in the same spirit as the trees in a city, fighting to become a forest; as the grasses and flowers pushing up cracks through asphalt and concrete; as the crazy raspberry ants that swarm into electrical boxes and chew through wires to short circuit computer systems; as the salmon that throw themselves relentlessly against (excruciatingly) slowly crumbling dams; as the monsoon rains that wash away bridges and rail lines; as the blizzards that topple power lines; as the forest fires that race through McMansion subdivisions.

Life doesn’t just want to live—it fights to live.

And that fight isn’t static; it isn’t an isolated moment in time. It’s a struggle growing, being cultivated by generation after generation of those individuals who say “enough” and take action, and by those who support them and tell their stories, replanting the seeds and watering a maturing culture of resistance.

Resistance is fertile. But we should also remember that it isn’t a stagnant fertility; it is incredibly active and dynamic. It isn’t a passive seed waiting to be planted; it has been in the soil for generations, slowly growing and spreading roots and tendrils and pushing up through cracks in the asphalt that have been decades in the making. With it grows the possibility—and indeed the promise—of that better world for which so many yearn and fight. As Arundhati Roy said, “another world is not only possible, she’s on her way. Maybe many of us won’t be here to greet her, but on a quiet day, if I listen very carefully, I can hear her breathing.”

Time is Short: Reports, Reflections & Analysis on Underground Resistance is a biweekly bulletin dedicated to promoting and normalizing underground resistance, as well as dissecting and studying its forms and implementation, including essays and articles about underground resistance, surveys of current and historical resistance movements, militant theory and praxis, strategic analysis, and more. We welcome you to contact us with comments, questions, or other ideas at undergroundpromotion@deepgreenresistance.org