by DGR News Service | Nov 6, 2019 | The Solution: Resistance

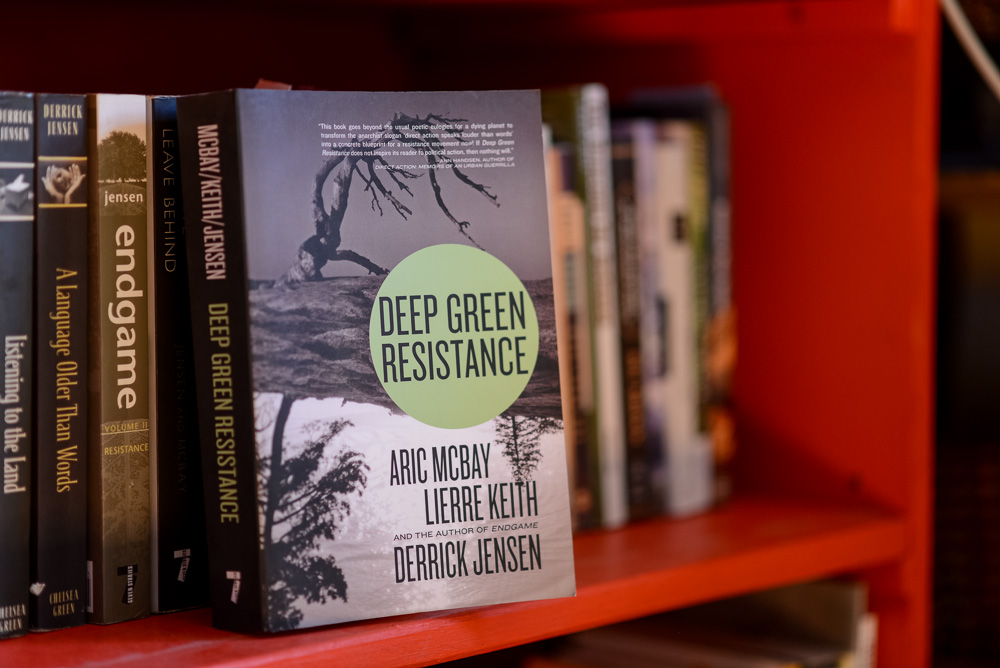

The DGR organization is largely based on the book Deep Green Resistance, which was written by Lierre Keith, Aric McBay, and Derrick Jensen and released in spring 2011.

Synopsis of the Book

Deep Green Resistance< starts where the environmental movement leaves off: industrial civilization is incompatible with life. Technology can’t fix it, and shopping—no matter how green—won’t stop it. To save this planet, we need a serious resistance movement that can bring down the industrial economy. Deep Green Resistance evaluates strategic options for resistance, from nonviolence to guerrilla warfare, and the conditions required for those options to be successful. It provides an exploration of organizational structures, recruitment, security, and target selection for both aboveground and underground action*. Deep Green Resistance also discusses a culture of resistance and the crucial support role that it can play. Deep Green Resistance is a plan of action for anyone determined to fight for this planet—and win

Read the Book

You can read Deep Green Resistance online for free, “name your donation” to download an ebook, or buy a physical copy of the book. We encourage you to buy the book directly from us, and not from Walmart, Amazon, etc. All proceeds from books purchased through the DGR website go directly to support the DGR aboveground organization.

Price $23 — includes free shipping (only within the U.S.). Click here to visit our store and buy the book. The book will ship in one to two weeks. Let us know if you’d like the book signed by Derrick Jensen and/or Lierre Keith.

Book Reviews

Words as Tactical Weapons (Canadian Dimension Magazine, 2012)

Other reviews:

“This book did not give me hope, but it did end my despair. Knowing that there is a subset of the population that, despite the enormity and seeming insurmountable scope of the destruction being wreaked on our planet, is willing to be brave enough to not only name the problems but DO something about it, has solidified a sense of purpose in myself. The mainstream environmental movement has always seemed somehow distracted, enamored with and addicted to the technological spectacle, making excuses for the continuation of our destructive civilization as long as there are impotent reforms and concessions – that ultimately mean nothing in the end. Deep Green Resistance identifies the problem and gives an outline of material solutions to stand up and fight for life, instead of either the magical thinking or nihilistic despair that is so prevalent in today’s environmental movements.”

– NH

“It took me two years to finish this book, because no sentence is wasted, every word written is heavy with meaning and import. I don’t agree with every detail, but I agree with so very much it had me shaking my head and underlining every other sentence. This book says things a lot of us know and think and never dare say: EXACTLY how bad things are, and who the REAL enemy is, with no false hope and no sugarcoating. A should-read for everyone.”

– FE

“This book is important for those who are aware of the many crises on the near horizon brought about by climate change. This book gives an action plan built upon love for the web of life and grounded in awareness that our current social structures (business and government) will not sufficiently change to avoid a cataclysm. The difficulty of it is that after reading, you have less of an excuse to not act.”

– KB

“Jensen, Keith, and McBay have written a clear call to arms for the health and well-being of the planet. They pointedly note the ineffectiveness of mere protest and reveal that only radical direct action has ever resulted in social change. But, more to the point, they note that they are not reforming the system, claiming it is merely flawed and in need of minor tweaks, nor do they envision an alternative consumerist industrialized society. They call for the end to the omnicidal culture that is systemically destroying the world and all of its inhabitants.

The case they make is unassailable if honestly argued. I know that those in thrall to the corporate killing machine will form a defense, but any honest person who carries the equation out to its logical end will come to the same understanding as these three avant garde thinkers.

If you have protested and been frustrated by the lack of results, if you’ve confronted and been ignored, if you’ve used every tactic that incrementalists deem appropriate and still feel as though you are losing ground (because you are), or if you merely want to understand why things are the way they are and seem to be getting worse, get this book. Read it. Read it again. Give it to your friends, your family, your co-workers, to everyone.

Remember, they are few, and we are many. Do it now before it is too late.”

– RD

by DGR News Service | Nov 4, 2019 | Movement Building & Support

At this pivotal moment in history, is nonviolent direct action the most effective tactic for bringing about urgent change? Should we continue to expect governments and corporations to listen and act, or has the time for that already passed? What does radical system change actually mean, in the context of the sixth mass extinction? And how can we work together to the same goals even when our tactics differ?

As the climate crisis worsens daily and governments worldwide fail to take meaningful action, it has never been more imperative to discuss all tactics available for resistance. Time is running out and those in power are not listening to mounting calls for radical change.

This panel discussion followed by audience Q&A aims to address the ways in which the environmental movement can rise to the unprecedented challenge facing humanity and all life on earth.

The panelists

Lierre Keith

Lierre is a writer, small farmer, and radical feminist activist. She is the author of six books, including The Vegetarian Myth: Food, Justice, and Sustainability, which has been called “the most important ecological book of this generation.” She is coauthor, with Derrick Jensen and Aric McBay, of Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. She’s also been arrested six times. You can read more about Lierre at www.lierrekeith.com.

Simon Be

Simon describes himself as a gravedigger, celebrant, pagan and a holy troublemaker. He’s committed to breaking the spells that civilisation has built around the myth of human superiority and exploring what it means to do what love requires in the context of dismantling a toxic system that’s devouring our living systems. He co-founded both Rising Up! and Extinction Rebellion and has been active with Earth First and other organisations.

Shahidah Janjua

Shahidah has been a feminist activist, writer and campaigner for 35 years, campaigning against pornography, prostitution, violence against women and trafficking in women and children. She has been active with feminist organisations including Justice For Women and the Rape Crisis Federation, and she is a founding member of the Women Into Politics project in the North of Ireland and a Refuge for Asian Women (Ashiana) in Sheffield. A writer and poet, her latest book of poetry, ‘Dimensions’, was published in Ireland in 2015. You can find out more about Shahida at www.sjanjua.net.

Nikki Clarke

Nikki has been an active anti-nuclear activist for nearly 20 years, and she is the co-founder of South West Against Nuclear, a direct-action based campaign that has had a specific focus on Hinkley over the last ten years. She has been arrested for non-violent protests on numerous occasions and has had several court cases for her actions against nuclear weapons, nuclear power and fracking in the UK. She gives talks and workshops across the UK about the impacts of radiation on health, and the health of women in particular, as well as nuclear policy.

After short presentations by all speakers on the panel, the floor will be open to audience questions to generate debate and discuss action-focused outcomes. We hope you can join us and be part of the conversation.

Ticket sales are to cover costs. Prices are set on a sliding scale: Concession, General and Solidarity – use the Eventbrite ticket link below to purchase. A limited number of free tickets are available for those unable to pay. Please message the organiser if you need to request a free ticket.

Doors open at 6:30pm for a 7:00pm start.

Conway Hall is a wheelchair accessible venue.

by DGR News Service | Oct 7, 2019 | Agriculture

Editor’s note: people with various diets are involved in Deep Green Resistance. Critical analysis of agriculture is central to our understanding.

By Lierre Keith

Start with a sixteen-year-old girl. She has a conscience, a brain, and two eyes. Her planet is being drawn and quartered, species by species. She knows it even while the adults around her play shell games with carbon trade schemes and ethanol. She’s also found information that leaves her sickened in her soul, the torment of animals that merges sadism with economic rationality to become the US food supply. Their suffering is both detailed and institution- ally distant, and both of those descriptors hold their own horrors.

A friend of mine talks about “the thing that breaks and is never repaired.” Anyone who has faced the truth about willful or socially- sanctioned cruelty knows that experience: in slavery, historic and con- temporary; in the endless sexual sadism of rape, battering, pornography; in the Holocaust and other genocides. You’re never the same after some knowledge gets through with you. But our sixteen-year-old has courage and commitment, and now she wants to do what’s right.

The vegetarians have a complete plan for her. It’s simple. You can create justice for animals, for impoverished humans, and for the earth if you eat grains and beans. That simplicity is part of its appeal, partly because humans have a tendency to like easy rules. But it also speaks to our desire for beauty, that with one act so much that’s wrong can be set right: our health, our compassion, our planet.

The problem is they’re wrong, not in their attempts to save the world, but in their solution. The moral valuing of justice over power, care over cruelty and biophilia over anthropocentrism is a shift in values that must occur if we are to save this planet. I didn’t call this book The Vegetarian Lie. I called it The Vegetarian Myth for a reason. It’s not a lie that animals are sentient beings currently being tortured for our food. It’s not a lie that the rich nations are siphoning off the life of the planet for literally oceans full of endless, empty plastic junk. It’s not a lie that most people refuse to face the systems of domination— their brute scale—that are destroying us and the earth.

But the vegetarians’ solution is a myth based on ignorance, an ignorance as encompassing as any of those dominating systems. Civilization, the life of cities, has broken our identification with the living land and broken the land itself. “The plow is the … the world’s most feared wrecking ball,” writes Steven Stoll. For ten thousand years, the six centers of civilization have waged war against our only home, waged it mostly with axes and plows. Those are weapons, not tools. Never mind reparations or repair: no peace is possible until we lay them down.

Those six centers were each driven by a tight cohort of creatures, at the center of which stand an annual plant or two. And humans have been so useful to corn and rice and potatoes, clever enough to conquer perennial polycultures as vast as forests, as tough as prairies, but not smart enough to see we’ve been destroying the world. The cohort has often included infectious diseases, diseases like smallpox and measles that jumped the species barrier from domesticated animals to humans. Humans who stood in the way of civilization’s hunger have been eradicated by the millions through civilization’s microbes, the first clear-cut preparing the way for the plow.

This is the ignorance where the vegetarian myth dead ends. Life must kill and we are all made possible by the dead body of another. It’s not killing that’s domination: it’s agriculture. The foods the vegetarians say will save us are the foods that destroy the world. The vegetarian attempt to remove humans from a paradigmatical pinnacle is commendable. And it’s crucial. We will never take our true place, one sibling amongst millions, sharing a common journey from carbon to consciousness, sacred and hungry, then back to carbon, without firmly and forever rejecting human dominion.

But in order to save the world we must know it, and the veg- etarians don’t, not any more than the rest of the civilized, especially the industrially so. Hens driven insane in battery cages are visible to vegetarians; both morally and politically that insistent sight is needed. What are invisible are all the other animals that agriculture has driven extinct. Entire continents have been skinned alive, yet that act goes unnoticed to vegetarians, despite the scale. How do they not see it? The answer is they don’t know to look for it. We are all so used to a devastated landscape, covered in asphalt and the same small handful of suburban plants, a biotic coup of its own. The whole east coast should be one slow sigh of wetland, interspersed with marsh meadows and old growth forest. It’s all gone, replaced by a McMonocrop of houses, shackles of asphalt, the brutal weight of cities.

Where the water goes shy, the trees should thin to savanna and prairie, although even there the wetlands should cradle the rivers. But there’s nothing left. The deltas and swamps, bison and black terns, have been turned into soy and wheat and corn. The capitalists say we should turn those into animal units; the vegetarians say we should dump them near the starving; I say we should stop growing them and let the world come back to life. Then we can take our place again, that place that the vegetarians claim to want, our place as participants.

We can dominate or we can participate but there is no way out. That’s what no one is telling that sixteen-year-old. The earth is liter- ally dying for wetlands and forests, rivers and prairies. And if humans would simply step aside, the world would do the work of repairing itself. But that repair involves death. It means letting the beavers eat the trees, letting the wolves eat the beavers, letting the soil eat us all. It means taking down every last dam and letting the salmon come home to lay their eggs and be eaten, and in the eating become the forest. This is the world as it should be, resiliently nourishing itself, the gift both given and received. No one is going to tell that sixteen- year-old girl the truth, because there’s no one left in her world who knows it.

Letting the beavers come back will mean that wetlands may well cover one-third of the land in places. Those wetlands can’t coexist with our roads and suburbs and agriculture. So where does your loyalty lie? Ask yourself that question as if you really mean it. Those wetlands would also feed us forever. To bring the wolves back would require a similar and massive contracture of human activity: they need land, wild land, sturdy with functioning forests and grasslands, not broken by cars, gouged into subdivisions, and coerced into mono- crops. You can’t have it both ways, vegetarians. If you want to save this world, including its animals, you can’t keep destroying it. And your food destroys it.

If you want rules about what to eat, I can give you some principles. They’re slightly more complicated than “Meat Is Murder,” but then the living world is complex, and beholding it should leave us all aching with awe. So start with topsoil, the beginning place. Remember, one million creatures per tablespoon. It’s alive, and it will protect itself if we stop assaulting it. It protects itself with perennial poly- cultures, with lots and lots of plants intertwining their roots, adding carbonaceous leaves, and working together with mycelium, bacteria, protozoa, making a new organism between them, the mycorrhiza that talks and nourishes and directs.

Defend the soil with your life, reader: there is no other organism that can touch the intelligence of what goes on beneath your feet.

So here are the questions you should ask, a new form of grace to say over your food. Does this food build or destroy topsoil? Does it use only ambient sun and rainfall, or does it require fossil soil, fossil fuel, fossil water, and drained wetlands, damaged rivers? Could you walk to where it grows, or does it come to you on a path slick with petroleum?

Everything falls into place with those three questions. Those annual monocrops lose on all three counts, unless you live in Nebraska, where it “only” fails the first two. Animal rights philosopher Peter Singer argues that you should only eat animal products if you can see their origin with your own eyes. While I agree with the impulse—to end the denial and ignorance that protect factory farming—this demand has to be much bigger: you should know where every bite of your food comes from. We need to end the denial and ignorance that protect agriculture. The worldview that gives any and all plant foods an automatic pass is profoundly blind to how those very foods devour living communities. Go look at Nebraska, where the native prairie is 98 percent gone. Even if you’ve never seen an Audubon bighorn or a swift fox, you must surely miss them.

We’ve all built this living world of gift and need, birth and return. To repair this planet, we must take our sustenance as part of those relationships instead of destroying them. We can pull the forest down or we can eat the deer that live there. We can rip up the grass or we can eat the bison that should stretch across the plains. We can dam the rivers or we can eat the fish that could feed us forever. We can turn biologic processes into commodities until the soil is salt and dust, or we can take our place as another hungering member of an ancient tribe, the tribe of carbon. All flesh is grass, wrote someone named Isaiah in a book I don’t usually quote. In Hebrew, the word translated as “flesh” is basar, meaning meat, something one eats. Isaiah understood what is no longer physically visible to us, living at the end of the world: we are all a part of one another, made from grass, become meat.

“But food requires destruction,” a vegan argued with me, in an e-mail exchange that went exactly nowhere. That is the final myth you must face, vegetarians. Because the food I am proposing, the food of our ancestors, whose paleolithic hearts and souls we still inhabit, does not require destruction. At this moment it would in fact require repair and restitution: the forests and grasslands mended, conquered territory ceded back to the earth for her wetlands. Steven Stoll sums up agriculture: “Humans became parasites of the soil.” It’s your food that has brought us to the end of the world.

My food builds topsoil. I’ve watched it happen. The mixture of grasses and trees, cousins in their own right, provides for the animals, who in their turn maintain and nourish by their simple biological functions of eating and excreting. On Joel Salatin’s Polyface Farm— the mecca of sustainable food production—organic matter has increased from 1.5 percent in 1961 to 8 percent today. The average right now in the US is 2-3 percent. In case you don’t understand, let me explain. A 6.5 percent increase in organic matter isn’t a fact for ink and paper: it’s a song for the angels to sing. Remember that pine forest that built one-sixteenth of an inch of soil in fifty years? Cue those angels again: Salatin’s rotating mixture of animals on pasture is building one inch of soil annually.

Peter Bane did some calculations. He estimates that there are a hundred million agricultural acres in the US similar enough to the Salatins’ to count: “about 2/3 of the area east of the Dakotas, roughly from Omaha and Topeka east to the Atlantic and south to the Gulf of Mexico.” Right now, that land is mostly planted to corn and soy. But returned to permanent cover, it would sequester 2.2 billion tons of carbon every year. Bane writes:

That’s equal to present gross US atmospheric releases, not counting the net reduction from the carbon sinks of existing forests and soils … Without expanding farm acreage or removing any existing forests, and even before undertaking changes in consumer lifestyle, reduction in traffic, and increases in industrial and transport fuel efficiencies, which are absolutely imperative, the US could become a net carbon sink by changing cultivating practices and marketing on a million farms. In fact, we could create 5 million new jobs in farming if the land were used as efficiently as the Salatins use theirs.

Understand: agriculture was the beginning of global warming. Ten thousand years of destroying the carbon sinks of perennial polycultures has added almost as much carbon to the atmosphere as industrialization (see Figure 5, opposite), an indictment that you, vegetarians, need to answer. No one has told you this before, but that is what your food—those oh so eco-peaceful grains and beans—has done. Remember the ghost acres and the ghost slaves? What you’re eating in those grains and beans is ghost meat, down to the bare bones of whole species. There is no reconciling civilization and its foods with the needs of our living planet.

To save the world, we must first stop destroying it. Cast your eyes down when you pray, not in fear of some god above, but in recognition: our only hope is in the soil, and in the trees, grasses, and wetlands that are its children and its protectors both.

“And why are we not doing this now?” is the clarion call Bane ends with. For a lot of reasons, most of them having to do with power. But a new populism could spring from this need, a serious political movement combining environmentalists, farm activists, animal rights groups, feminists, indigenous people, anti-globalization and relocalization efforts—all of us who are desperate for a new, and living, world.

That’s the real reason I’ve written this book. The earth, our only home, needs that movement, and she needs it now. The only just economy is a local economy; the only sustainable economy is a local economy. Come at it from whichever angle matches your passion, the answers nest around the same central theme: humans have to draw their sustenance from where they live, without destroying that place.

That means that first we must know that place. I can’t give you a list of what to eat because I don’t know what can live where you do. I can only give you the principles I’ve already laid out. Then you’ll have to ask questions. How much rain falls where you are? What’s the terrain, the temperature, the soil? Dairy cattle, for instance, do great things where I live in cold, wet New England. I wouldn’t suggest them in dry New Mexico.

Understand my point. Farming—the growing of annual mono- crops—will never be sustainable. Our only chance is a judicious and humble human participation in perennial polycultures. We can do that poorly, as demonstrated in the overgrazing due to population pressures that is currently turning grasslands to desert the world over. Or we can do it well, like the Fulani of Africa, with a largely unbroken line reaching back to a pre-human time four million years ago.

How much can we change the landscape before participation becomes destruction? Especially when our impact may not be visible for a thousand years? Should we, for instance, use fire? Fire will drive out some species, both plant and animal, and encourage others. Where I live, sugar maples are iconic. Yet five hundred years ago, they wouldn’t have been here, or not many of them. The burning practices of Native Americans kept the forest here shifted toward fire-resistant and mast-bearing trees. That information was a shock

to my system: don’t mess with my maple trees. But Brian Donahue makes the point that as long as there has been a forest in New Eng- land, there have been humans living in it. We belong here, too, if we would just behave like it. The pristine forest free of human influence has never existed here, so is it the ideal we should be aiming for?

If so, that ideal must presuppose a devastated landscape some- where else and an interstate highway system to transport the foods produced out of it. None of this can last: not the devastation, the fossil fuel, the distance. We need to eat where we live and our food must be part of the repair of our home.

Let’s look at an example. Do dairy cows belong in New Eng- land? In the here and now, as I make my personal and political decisions about breakfast, are cows on the side of good or do they need to be hauled up Mount Doom?

Dairy cattle were brought over from Europe four hundred years ago. Does that rule them out automatically? But if you dig deeper into the past, there were once thirty-three more genera of large mammals on this continent, relatives of horses, cows, elephants, giraffes— and not that long ago, a mere 12,000 years. Their absence has left evolutionary widows, trees like honey locust and osage orange that are in decline because they need large herbivores to help them.9 In that sense, horses and cows were perhaps reintroduced with the spread of Europeans. So dig deeper still. Are these new animals similar enough to the ones that are gone, or do their divergences make them destructive assailants on the land base? There were, for instance, once equids here, but they had cloven hooves and no upper teeth. The result of the solid hooves and incisors is “ecological havoc.”10 The feral horses from Europe destroy desert seeps and springs, smother spawning gravel with silt, and strip grasslands to bare dirt. The most in-depth analysis of nineteen study sites found severe damage to “soils, rodents, reptiles, ants, and plants.” That damage puts species from desert tortoises to the endangered Lahontan cutthroats at risk.

There are clearly brittle landscapes too fragile for cows—especially for dairy cows—as well. Most of the west is more suited to the animals that were already there—buffalo, pronghorns, elk—and that’s what the people there should be eating. So that’s a directive: restore the prairie, long grass and short, and the drylands, and return their animal cohorts. Then think long and hard about other megafauna and their place on this continent. Do the grasslands and savannas want them back, or their relatives that still survive? What about the honey locust and osage orange, who need their large seeds to be di- gested and carried by large herbivores? Is their dying simply evolution at work? If we humans reintroduce some creature that might fulfill that function and restore the range of those trees, is that also evolu- tion? Or is that interference?

And I still need to decide about breakfast.

Cattle on pasture in my climate can easily be sustainable. Joel Salatin is certainly proving that. The model is sound and the climate and rainfall are suitable. But pasture isn’t the natural landscape of New England. Forests, wetlands, and marsh meadows are. The Europeans’ cows first grazed in those meadows and forests. As the beaver were eradicated, the wetlands and marsh meadows disappeared. Meanwhile, in Europe, experimentation with plant admixtures improved the sustainability of pastures dramatically. How does turning some forest land into pasture compare with the habitat shift of burning? Both of these are activities that, done well, will build topsoil and provide for human sustenance essentially forever. So how much impact are we allowed to have? The entire rainforest is a human project. Small patches are burned by the indigenous like the Lacandon Mayan, and then planted in a secession of eighty different crops, including the vines, shrubs, and trees that will take over when the plot has been abandoned—though “abandoned” is not really an accurate description, as the plot will be revisited in a twenty-year rotation, and will meanwhile produce food, fiber, and building materials, as well as a home for the wild animals that serve as protein.

Which brings me to my point. It wasn’t pasture that brought down the northeast forest. It was coal. As long as the human economy was based on wood in this cold climate, people more or less took care of the forest, because they needed it. Coal was what reduced the forest to simply one more commodity, and the land that forests grew on was more profitably used for wool breeds of sheep. What will happen as the price of oil first climbs past what the average household can pay, then past the effort worth retrieving it from the ground? Will New England be cleared from the Atlantic Ocean to the Housatonic River as people freeze to death? Or will the rural areas and private woodlot owners be able to hang onto their parts of this young forest, knowing that without it they, too, will soon freeze? Will we be facing a war not over Middle Eastern oilfields, but over trees in the Berkshires?

And I still need to decide about breakfast.

I can raise these issues, but maybe I can’t answer the questions.

I know that whatever we’re eating has to build soil, and if it doesn’t, it has to be struck forever from the human menu. It has to be part of a self-replicating community, where life and death are inseparable in the process of nourishment. Everyone has to give back, through the labor of their life functions, and then through the nutrients stored in their bodies. Our food can’t be based on fossil fuel, for nitrogen or energy. Nor can it use fossil water, or indeed any water that empties a river.

Dairy cows, where I live, meet those criteria and more. But is the change in species composition wrought by human-set fire on the acceptable side of the line while the change required for pasture placed in the unacceptable column? Then what we will eat instead will be deer and moose. Both of those, along with bison, migrated here from Eurasia not too long ago, maybe 12,000 years. They filled in niches left empty by the megafaunal extinctions. They’re Eurasian trans- plants, too. Do you see how complicated this gets?

And I still need my breakfast.

In the end, I do have my own answers to offer, of course, but they involve a bit more than drinking soy milk. Agriculture has to stop. It’s been a ten thousand year disaster, as life on earth will tell us if we listen. Writes William Catton:

The breakthrough we called industrialization was fundamentally unlike earlier ones. It did not just take over for human use another portion of the web that had previously supported other forms of life. Instead, it went underground to extract carrying capacity supplements from a finite and depletable fund …

As discussed earlier, I think the beginning of the fossil fuel age does mark a new level of human destructiveness, but he’s wrong in his characterization of agriculture as simply taking over more ecological niches. Agriculture is extractive: soil is depletable and “peak soil” was ten thousand years ago, on the day before agriculture began. We’ve been on the down curve ever since.

So agriculture has to stop. It’s about to run out anyway—of soil, of water, of ecosystems—but it would go easier on us all if we faced that collectively, and then developed cultural constraints that would stop us from ever doing it again.

Where I live, the wetlands need to return to cover the land in a soft, slow blanket of water. They will be a home for a lush multitude of species, many of which—waterfowl, moose, fish—could feed us. The rivers need to be undammed. And the suburbs and the roads need to be abandoned. I have no great solutions for how to make that economically feasible: I sincerely doubt it’s possible. I only know it has to happen, no matter how much we resist.

This is an excerpt from “To Save the World” in the book The Vegetarian Myth by Lierre Keith. Click here to order directly from the author.

by DGR News Service | Oct 6, 2019 | Movement Building & Support

We are thrilled & honored to announce that Prairie Protection Colorado and Deep Green Resistance are bringing Derrick Jensen & Lierre Keith to Denver, Colorado on Sunday, Oct 6, 12:30 pm Mountain Time, 18:30 UTC.

The event will be live streamed on the Deep Green Resistance Facebook Page.

Video will be available after the event on our YouTube page as well.

Derrick Jensen

Derrick Jensen is a leading voice of cultural dissent. He explores the nature of injustice, how civilizations devastate the natural world, and how human beings retreat into denial at the destruction of the planet.

Derrick has authored 27 books and counting including The Myth of Human Supremacy, Endgame Volume 1 & 2, The Culture of Make Believe and A Language Older than Words. He co-authored the book, Deep Green Resistance, inspiring people from all over the world to resist the systemic insanity of those who are killing the planet.

derrickjensen.org

Lierre Keith

Lierre Keith is an acclaimed writer, radical feminist, food activist, and environmentalist. Her work centers on civilization’s violence to the earth, male violence against women and the need for serious resistance to both. Her book The Vegetarian Myth: Food, Justice, and Sustainability has been called “the most important ecological book of this generation.” She co-authored the book, Deep Green Resistance, inspiring people from all over the world to resist the systemic insanity of those who are killing the planet.

lierrekeith.com

by DGR News Service | Oct 4, 2019 | The Solution: Resistance

This is excerpted from Chapter 15, “Our Best Hope,” in the book Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. It was written by Lierre Keith.

In our story, the first direct hit to industrial infrastructure is likely to be something more pragmatic and less daring, like the electric grid. Our actionists have planned well. Remember the four criteria for target selection: the grid is accessible, vulnerable, and critical, and while it is recuperable, the abundance of the first three criteria could potentially make that recuperability more theoretical than practical.

The underground networks can hit a few nodes at once, and the unconnected affinity groups, well versed in DEW and the DGR grand strategy, can follow up on the vulnerable targets to which they have access. The first DGR blackout could last days or even weeks.

An instructive event to consider from recent history is the Northeast Blackout of 2003. On August 14, a huge power surge caused a rolling blackout over a large section of northeastern US and Canada, affecting fifty-five million people. This event brought home how very delicate power grids are. Because electricity can’t really be stored, it has to be consumed within a second of being produced or else dumped. Supply and demand have to be matched very precisely or costly infrastructure can be seriously damaged by either too much or too little power. The grid has built-in protective relays to guard against flashovers, which dis- connect any line that has a sudden surge in power. But with such tight correspondences, it’s amazing that any of us have reliable electricity.

August 14 saw a cascading failure that started with electric arcs between a few overhead lines and some trees in northeast Ohio. By the time the grid had finished responding, power plants all across the Northeast had gone offline and a full-fledged blackout was on. A total of 256 electric power plants shut down, and electricity generation dropped by 80 percent.

But the phrase “cascading failure” applies to a lot more than the grid. Oil refineries couldn’t operate and neither could the nine nuclear power plants in the region. Gas stations couldn’t pump gas. Air, rail, and even car traffic halted. The financial centers of Chicago and Manhattan were immobilized, and Wall Street was completely shut down. The Internet only worked for dial-up users, and then only as long as their batteries lasted. Most industries had to stop, and many weren’t running again until August 22. That last includes the auto industry. The major television and cable networks had disruptions in their broadcasts. In New York City, both restaurants and neighbors cooked up everything on hand and gave it away for free as the perishables were just going to have to be thrown out. Meanwhile, the Indigo Girls concert went on as planned in Central Park. And the New Jersey Turnpike stopped collecting tolls.

I don’t know about you, but I’m not seeing any drawbacks here. The cascade was broad and deep, if short. Fossil fuel use was seriously decreased; nuclear power plants rendered useless; oil went unrefined in northern New Jersey, my child’s eyes’ vision of Mordor in that last whisper of wetlands; the rich were kept from draining the poor; and the flood of lies and vicious media images stopped drowning our hearts, our children, and our culture for a brief night. And there were parties with neighbors and music on top of that.

The DEW activists will be soundly condemned, and not just by the mainstream, but by Big Eco, and by many grassroots activists. This is to be expected. Our actionists need to prepare for it emotionally, socially, organizationally. It can’t be helped. Remember the goal: to disrupt and dismantle industrial civilization. Judged by that goal, our actionists’ first attack on the electric grid has been a raging success. And nothing breeds success like success. More groups form, more cells divide in the network. Maybe a whole arm is dedicated to the grid while others go on to other targets. Like the tar sands. The pipelines carrying tar sands oil from Alberta to the coast are 800 miles long; sab- otage is too easy. Meanwhile, the equipment necessary for the massive scale of the tar sands extraction is almost inconceivable: twenty stories high and counting. Some of it has to be carried on trucks with ninety tires on twenty-four axles, weighing a total of 917,000 pounds, which is so heavy that two auxiliary trucks are needed to help push. These trucks need special permits and are only allowed on the highway during daylight hours.

Our story is accelerating. A victory for the Tar Sands Brigade comes on the night the draglines are torched, and a few of the factories that make them are incinerated. Does Suncor get more? Yes. And those are burned as well, somewhere on their vulnerable route between their arrival point in Bellingham, Washington, and their departure point in Fort McMurray, Alberta.

Again, Big Oil, Big Coal, and Big Eco all condemn the activists. The public overwhelmingly hates them. But in the Athabasca River, the northern pike and the tundra swans love them. More equipment is pur- chased. Our actionists respond by sinking the replacements on the boats before they even touch shore and, for added emphasis, a mid- night demolition of a corporate headquarters or two. Native Athabasca Chipewyan and Mikisew Cree elders and more than a few Clan Mothers are smiling all week. The warriors, meanwhile, ask some questions, starting with: kakipewîcîhwin cî? Will you come and join me? It’s up to them to decide whether to move from protecting their community to offensive action. The young, of course, are all “Yes.” When the next DGR blackout rolls through the middle of the continent, a sudden blast blazes across the night as a key bridge comes down on Provincial Route 63. Try getting that million-pound equipment across the river now.

Only a few hundred people are involved at this point. There are three networks, one in the northeast US, one in the Pacific Northwest, and a smaller one in the upper Midwest. There are also affinity groups in Vancouver, Asheville, Burlington, Austin, Guelph, Montreal, and some of the First Nations’ warrior societies are now involved.

And in this story, there are people who want to join, but can’t. They make the decisions they have to make, and do what they can instead. They translate a scaled-down version of this book—the marrow, the soul—into Hindi and Spanish and Mandarin and Sámi. Deep Green Resistance becomes Résistance Verte Profonde and then Molaskaskwi Aod- wagan, slipping south into Resistencia Verde Radical, crossing oceans into Djúpur Grænn Mótspyrna, Dunkelgrüner Widerstand, Mörktgrönt Motstånd, Paglaban Malalim Berde. The question only changes its sound, never its heart: K’widzawidzi nia? Ti unirai a me? Kayo ay sumali sa akin? The question is asked and asked and asked, whispered like a prayer in that moment the heart shifts from petition to thanksgiving: will you join me? Until “me” becomes “us,” because finally a resistance has quickened.

Click here to read the book for free online, or to download an eBook. Click here to purchase a paper copy. The book has now been translated into German, Spanish, and Russian. If you wish to help with additional translation work or get involved with Deep Green Resistance, please contact us.