by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 10, 2018 | Strategy & Analysis

by Max Wilbert / Deep Green Resistance

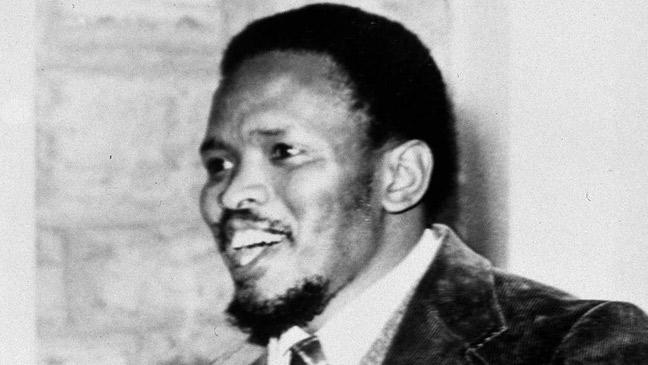

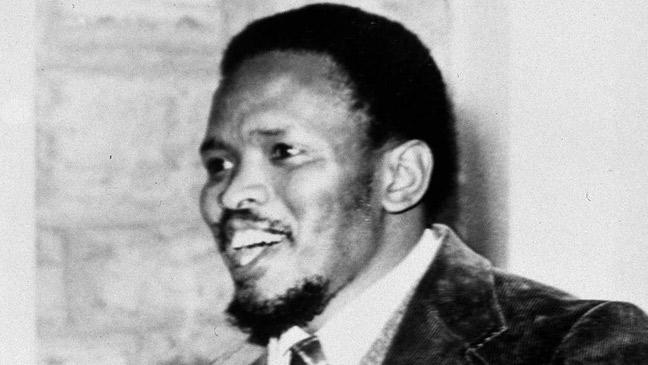

“Deep down, every liberationist is an optimist.” – Steve Biko

Steve Biko was a South African anti-apartheid activist and organizer who was murdered by the secret police in 1978. He was 32 years old when he was tortured and beaten, resulting in his death. “I Write What I Like” is a collection of writing by Biko and includes some commentary.

The collection is defined by radicalism. Biko was a believer in the mantra that freedom cannot be given, only taken. In this idea lies the core of why the liberal solution to South African apartheid remained incomplete, resulting in a highly unequal, racialized capitalist society. This is the difference between “equality” under the law and true liberation.

Biko understood that racism and apartheid were not simply technical problems. “One needs to understand the basics before setting up a remedy,” he writes. “A number of organizations now currently ‘fighting against apartheid’ are working on an oversimplified premise. They have taken a brief look at what is, and have diagnosed the problem incorrectly. They have almost completely forgotten about the side effects and have not even considered the root cause. Hence whatever is improved as a remedy will hardly cure the condition.”

Biko’s philosophy of Black Consciousness was built on undermining both the political structures that upheld apartheid as well as the internalized inferiority and superiority that still characterize race relations in many locations worldwide. He rejected integration for its own sake, recognizing that mainstream integration ideas are “white man’s integration—an integration based on exploitative values. It is an integration in which black will compete with black, using each other as rungs up a step ladder leading them to white values… these are the concepts which the Black Consciousness approach wishes to eradicate from the black man’s [sic] mind before our society is driven to chaos by irresponsible people from Coca-Cola and hamburger cultural backgrounds.”

He aimed to uphold African cultural values as important, writing “The easiness with which Africans communicate with each other is not forced by authority but is inherent in the make-up of African people… this is a manifestation of the interrelationship between man and man [sic] in the black world as opposed to the highly impersonal world in which Whitey lives.”

He understood that oppressive systems maintain their power primarily by the consent of the oppressed, which is gained via coercion, psychological tricks, propaganda, fear, and so on.

This is the reason that Biko was confident in the ability of non-violent aboveground political organizing to liberate South Africa. He was not a pacifist, and spoke in favor of the militant organizations (ANC and the PAC) that operated underground during his most active years.

These organizations had limited effectiveness in that context, but Biko strove to forge multi-generational alliances regardless, recognizing the primacy of shared goals. His approach to other groups was “tough, even aggressive language” tempered “with a basically friendly underlying spirit.”

Biko was a leader, but not an authoritarian. He promoted initiative rather than centralization. This proved to be key when many figures within various resistance movements were banned from participation in public life or sent to prison on the remote Robben Island.

He was a highly effective organizer, as one passage from his friend Aelred Stubbs C.R. makes clear. “Although Steve could hold no office in BPC because of his banning order he was constantly being consulted. It was amazing how much he knew… more than once he warned me not to get too close to certain people, white or black, whose contacts were less than desirable. He was always right. He never spoke against anyone if he could possibly help it. Even when he did, it was always in a particular context… There was this fierce integrity about them all. If you were with them you were in, and everything was given and taken. If in any way you were furthering your own ends, or trying to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds, you were out.”

Biko, like all historical figures, was no saint. His behavior was frequently sexist, and he derided feminism as an irrelevance—not an uncommon attitude at the time (or today), but inexcusable in someone fighting for justice. Like with other historical figures, we can learn from his weaknesses as well as his strength. In 2018, those lessons are still as relevant as ever.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 6, 2018 | Listening to the Land

Featured image: salmon eggs

Editor’s note: This is an edited transcript of Derrick Jensen’s talk, which you can view on Deep Green Video.

by Derrick Jensen / Deep Green Resistance

There are hundreds of ways to kneel and kiss the ground.

There are hundreds of ways to pray. You can walk through a forest. You can sit by a pond. You can watch the air turn into clouds and then slowly dissipate. You can lie on your back and look at the stars.

Those are crucial acts of prayer and sanity.

But with the world being killed, the prayers we really need today are actions.

We need people to not merely walk through the forest, but to defend it from being cut. And we need people to not merely look at the pond, but to make sure that those who live in the pond can survive this culture.

A prayer without actions to work toward protecting whomever you love is not a prayer. It’s not even a wish, but it’s almost a blasphemy.

I often said that I don’t hope that salmon survive, but I’ll do whatever it takes to make sure that salmon survive.

An Anishinaabe woman wrote to me and said: “I hear what you’re saying, and it is an obscenity to hope that salmon survive, or pray that salmon survive, when you’re not doing anything in the real world to help them survive. But after you have taken out the dam, you have to pray that the river accepts your offering of the dam removal, and does its own work then.”

I completely agree.

So we have to do everything that we can, and then we have to pray that the earth accepts our offering and accepts our prayer and that the salmon come home.

“Endangered Redfish Lake sockeye salmon eggs” by NOAA Fisheries West Coast is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 3, 2018 | Listening to the Land

by Boris Forkel / Deep Green Resistance Germany

Call me crazy, but I spent the last evening sitting in my garden and telling the first toad I met this year what I do and why. I told her about Deep Green Resistance, about the destruction of the natural world by our culture, and I asked her to tell me how she and her kind perceive all this.

I don’t know if I understood her correctly, but what I heard was: “Well, too many of us are dying. We know that some of you are trying to help us. That’s not enough. It has to stop.“

It doesn‘t matter if I‘m projecting or not. The toad is right.

She wasn’t shy, she sat quietly right next to me, moved a little bit every now and then and looked at me with beautiful red, serious eyes.

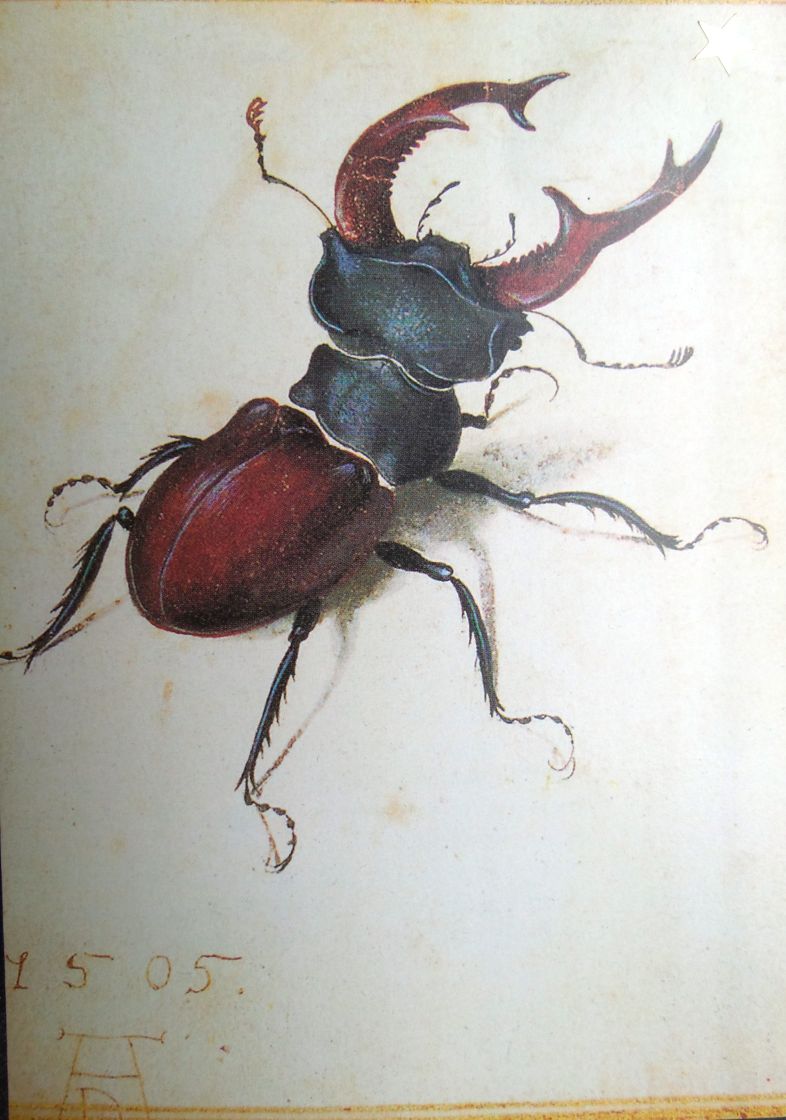

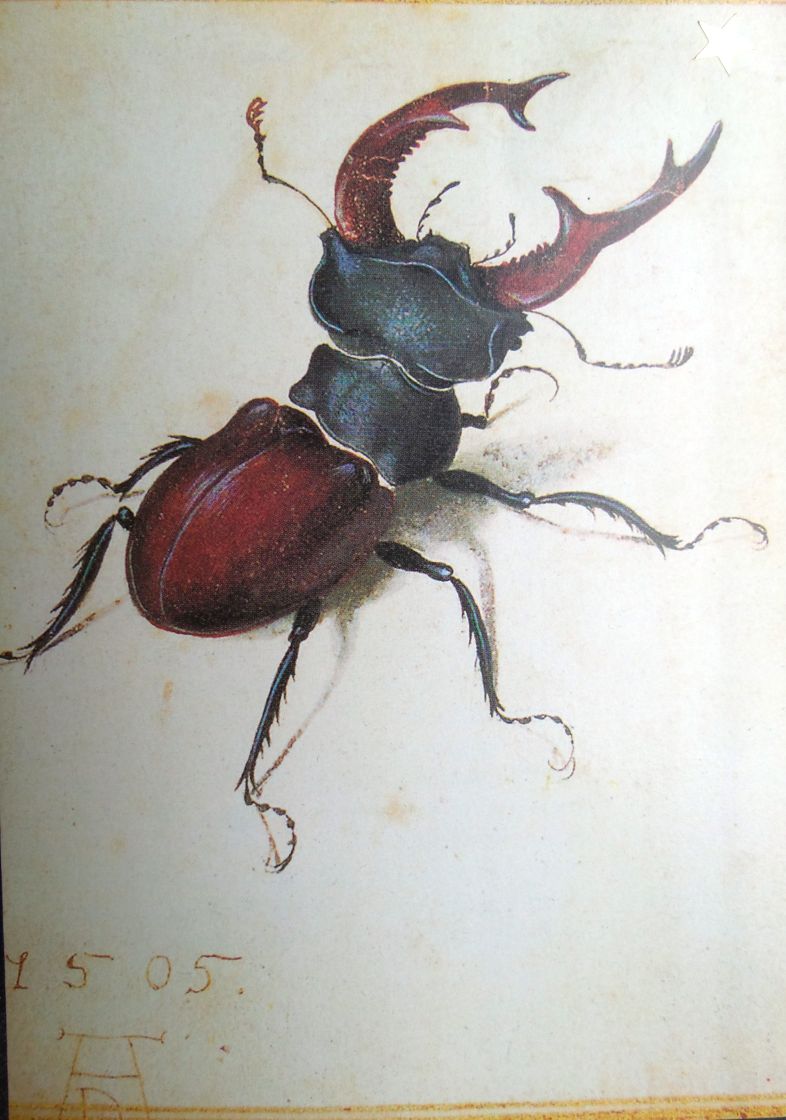

I do this regularly, I go to the wildest places that still exist here and listen to nature. I see different kinds of insects, wild bees, bumblebees, mosquitos, beetles, a few dragonflies. I see – mostly hear – birds, but I can only distinguish about five or six species. I love the call of the codger when it gets dark.

I know that the stag beetles come out of the ground at the beginning of June, where they have lived for three years as increasingly fattening grubs, to fly with a huge hum into the summer forest, where they will live exclusively from the sap of the rare old oaks their females prepare, since the males cannot bite the bark because of their huge antlers. Every June, I wait in my garden to welcome them. Towards the end of the summer they carry out their ecstatic fights and mating rituals, until after spending only three months as Europe‘s most giant beetles, they die and serve hungry birds as autumn delicacy.

I see squirrels, bats, toads, grass frogs and spotted salamanders. Sometimes I meet bigger animals: Wild boars, badgers, foxes, deer, but these are still scared of me and usually flee quickly.

The European bison, or wisent, that used to inhabit this forest, I only know from the zoo. But even the ones that are forced to live in captivity are gigantic, beautiful, trusting and kind. They look at me with loving eyes, each of them asking the same question:

Why?

Twice in my life I‘ve seen a snake. The first encounter was a European adder, many years ago in a village in the Odenwald (the forest where I live), when I was a school kid. The second one was a giant garter snake in my garden a few months ago. She (or he) was enjoying the sun, lying on a large oak tree that recently had been killed by a storm.

After this encounter, I wanted to learn more about them. I read that garter snakes used to be treated as house snakes and were considered holy animals that bring happiness and blessing. The garter snake was worshipped by numerous European peoples until the late Middle Ages, and appears in many myths. People fed garter snakes milk, just as the Indian villagers do in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book with their holy village cobra.

Today, you are very lucky if you see a garter snake once in your life.

It’s getting dark. I look at the stars and the full moon. I speak to them and all the animals, plants and living beings that surround me. I tell them what I do and why, and I say prayers. I declare my loyalty. I tell them that I am one of them, and that I will do everything in my power to help them. They’re my relatives.

I’m asking them to tell me the most important things I can do for them. I tell them that I love them.

The toad is still sitting next to me. She (or he) looks at me, lets me take a foto and politely waits until I’m done talking to her. Then she slowly trots towards the pond I have build for her kind to inhabit.

Like thousands of times before, I walk the way from my garden to my small apartment in the city. Like thousands of times before, I look down over the Neckar River to see Babylon. I fear Babylon. I’m terrified of Babylon.

The Neckar River once was called Germany’s wildest river, but it has been raped for at least 2000 years, since the Roman invaders drained parts of it to build the old bridge that is still in place today. Nowadays, the River essentially serves as a road for the many freighters that are desperately trying to satisfy the insatiable hunger of Babylon. Like the Rhine, it had been full of salmon in the past, but this was so long ago that no human people can remember. I’m sure the trees still know.

During the last two years beavers return, after being absent for about 150 years. There are supposed to be about three thousand of them again in Baden-Württemberg. The state government is considering to kill about half of them because they are allegedly damaging trees.

The natural world is full of wisdom. So often I‘ve sat here or there, listening, speaking, praying. The river, the forest and all the creatures who still live here spreak different languages and have different messages. They have taught me a lot, and I have a lot more to learn. But in one thing they all agree:

It has to stop. Babylon Apocalypse.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 2, 2018 | Pornography

Featured image: Edgar Degas’ “Scène de guerre au Moyen-âge,” 1865, is one of the exhibits said to be inspired by Sade RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) / Gérard Blot

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Culture of Resistance” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance

While the alternative culture “celebrates political disengagement,” what it attacks are conventions, morals, and boundaries. It comes down to a simple question: Are we after shock value or justice? Is the problem a constraining set of values or an oppressive set of material conditions? Remember that one of the cardinal points of liberalism is that reality is made up of values and ideas, not relationships of power and oppression. So not only is shock value an adolescent goal, it’s also a liberal one.

This program of attacking boundaries rather than injustice has had serious consequences on the left, and to the extent that this attack has won, on popular culture as a whole. When men decide to be outlaw rebels, from Bohemians to Hell’s Angels, one primary “freedom” they appropriate is women. The Marquis de Sade, who tortured women, girls, and boys—some of whom he kidnapped, some of whom he bought—was declared “the freest spirit that has yet existed” by Guillaume Apollinaire, the founder of the surrealist movement.63 Women’s physical and sexual boundaries are seen as just one more middle-class convention that men have a right to overcome on their way to freedom. Nowhere is this more apparent—and appalling—than in the way so many on the left have embraced pornography.

The triumph of the pornographers is a victory of power over justice, cruelty over empathy, and profits over human rights. I could make that statement about Walmart or McDonalds and progressives would eagerly agree. We all understand that Walmart destroys local economies, a relentless impoverishing of communities across the US that is now almost complete. It also depends on near-slave conditions for workers in China to produce the mountains of cheap crap that Walmart sells. And ultimately the endless growth model of capitalism is destroying the world. Nobody on the left claims that the cheap crap that Walmart produces equals freedom. Nobody defends Walmart by saying that the workers, American or Chinese, want to work there. Leftists understand that people do what they have to for survival, that any job is better than no job, and that minimum wage and no benefits are cause for a revolution, not a defense of those very conditions. Likewise McDonalds. No one defends what McDonalds does to animals, to the earth, to workers, to human health and human community by pointing out that the people standing over the boiling grease consented to sweat all day or that hog farmers voluntarily signed contracts that barely return a living. The issue does not turn on consent, but on the social impacts of injustice and hierarchy, on how corporations are essentially weapons of mass destruction. Focusing on the moment of individual choice will get us nowhere.

The problem is the material conditions that make going blind in a silicon chip factory in Taiwan the best option for some people. Those people are living beings. Leftists lay claim to human rights as our bedrock and our north star: we know that that Taiwanese woman is not different from us in any way that matters, and if going blind for pennies and no bathroom breaks was our best option, we would be in grim circumstances.

And the woman enduring two penises shoved up her anus? This is not an exaggeration or “focusing on the worst,” as feminists are often accused of doing. “Double-anal” is now standard fare in gonzo porn, the porn made possible by the Internet, the porn with no pretense of a plot, the porn that men overwhelmingly prefer. That woman, just like the woman assembling computers, is likely to suffer permanent physical damage. In fact, the average woman in gonzo porn can only last three months before her body gives out, so punishing are the required sex acts. Anyone with a conscience instead of a hard-on would know that just by looking. If you spend a few minutes looking at it—not masturbating to it, but actually looking at it—you may have to agree with Robert Jensen that pornography is “what the end of the world looks like.”

By that I don’t mean that pornography is going to bring about the end of the world; I don’t have apocalyptic delusions. Nor do I mean that of all the social problems we face, pornography is the most threatening. Instead, I want to suggest that if we have the courage to look honestly at contemporary pornography, we get a glimpse—in a very visceral, powerful fashion—of the consequences of the oppressive systems in which we live. Pornography is what the end will look like if we don’t reverse the pathological course that we are on in this patriarchal, white-supremacist, predatory corporate-capitalist society.… Imagine a world in which empathy, compassion, and solidarity—the things that make decent human society possible—are finally and completely overwhelmed by a self-centered, emotionally detached pleasure-seeking. Imagine those values playing out in a society structured by multiple hierarchies in which a domination/subordination dynamic shapes most relationships and interaction.… [E]very year my sense of despair deepens over the direction in which pornography and our pornographic culture is heading. That despair is rooted not in the reality that lots of people can be cruel, or that some number of them knowingly take pleasure in that cruelty. Humans have always had to deal with that aspect of our psychology. But what happens when people can no longer see the cruelty, when the pleasure in cruelty has been so normalized that it is rendered invisible to so many? And what happens when for some considerable part of the male population of our society, that cruelty becomes a routine part of sexuality, defining the most intimate parts of our lives?64

All leftists need to do is connect the dots, the same way we do in every other instance of oppression. The material conditions that men as a class create (the word is patriarchy) mean that in the US battering is the most commonly committed violent crime: that’s men beating up women. Men rape one in three women and sexually abuse one in four girls before the age of fourteen. The number one perpetrator of childhood sexual abuse is called “Dad.” Andrea Dworkin, one of the bravest women of all time, understood that this was systematic, not personal. She saw that rape, battering, incest, prostitution, and reproductive exploitation all worked together to create a “barricade of sexual terrorism”65 inside which all women are forced to live. Our job as feminists and members of a culture of resistance is not to learn to eroticize those acts; our task is to bring that wall down.

In fact, the right and left together make a cozy little world that entombs women in conditions of subservience and violence. Critiquing male supremacist sexuality will bring charges of being a censor and a right-wing antifun prude. But seen from the perspective of women, the right and the left create a seamless hegemony.

Gail Dines writes, “When I critique McDonalds, no one calls me anti-food.”66 People understand that what is being critiqued is a set of unjust social relations—with economic, political, and ideological components—that create more of the same. McDonalds does not produce generic food. It manufactures an industrial capitalist product for profit. The pornographers are no different. The pornographers have built a $100 billion a year industry, selling not just sex as a commodity, which would be horrible enough for our collective humanity, but sexual cruelty.67 This is the deep heart of patriarchy, the place where leftists fear to tread: male supremacy takes acts of oppression and turns them into sex. Could there be a more powerful reward than orgasm?

And since it feels so visceral, such practices are defended (in the rare instance that a feminist is able to demand a defense) as “natural.” Even when wrapped in racism, many on the left refuse to see the oppression in pornography. Little Latina Sluts or Pimp My Black Teen provoke not outrage, but sexual pleasure for the men consuming such material. A sexuality based on eroticizing dehumanization, domination, and hierarchy will gravitate to other hierarchies, and find a wealth of material in racism. What it will never do is build an egalitarian world of care and respect, the world that the left claims to want.

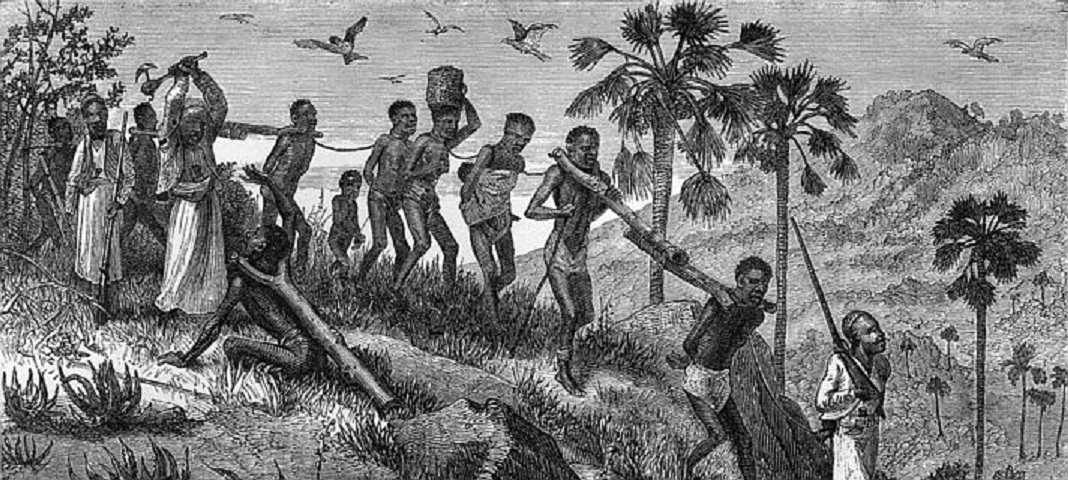

On a global scale, the naked female body—too thin to bear live young and often too young as well—is for sale everywhere, as the defining image of the age, and as a brutal reality: women and girls are now the number one product for sale on the global black market. Indeed, there are entire countries balancing their budgets on the sale of women.68 Is slavery a human rights abuse or a sexual thrill? Of what use is a social change movement that can’t decide?

We need to stake our claim as the people who care about freedom, not the freedom to abuse, exploit, and dehumanize, but freedom from being demeaned and violated, and from a cultural celebration of that violation.

This is the moral bankruptcy of a culture built on violation and its underlying entitlement. It’s a slight variation on the Romantics, substituting sexual desire for emotion as the unmediated, natural, and privileged state. The sexual version is a direct inheritance of the Bohemians, who reveled in public displays of “transgression, excess, sexual outrage.” Much of this ethic can be traced back to the Marquis de Sade, torturer of women and children. Yet he has been claimed as inspiration and foundation by writers such as “Baudelaire, Flaubert, Swinburne, Lautréamont, Dostoevski, Cocteau, and Apollinaire” as well as Camus and Barthes.69 Wrote Camus, “Two centuries ahead of time … Sade extolled totalitarian societies in the name of unbridled freedom.”70 Sade also presents an early formulation of Nietzsche’s will to power. His ethic ultimately provides “the erotic roots of fascism.”71

Once more, it is time to choose. The warnings are out there, and it’s time to listen. College students have 40 percent less empathy than they did twenty years ago.72 If the left wants to mount a true resistance, a resistance against the power that breaks hearts and bones, rivers and species, it will have to hear—and, finally, know—this one brave sentence from poet Adrienne Rich: “Without tenderness, we are in hell.”73

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 29, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

Editor’s note: this is an edited transcript of Derrick Jensen’s talk, which you can listen to here.

What does it mean to decolonize my heart and mind, and how do I go about doing that?

by Derrick Jensen / Deep Green Resistance

Many indigenous people have said to me that the first and most important thing we have to do is decolonize our hearts and minds. Part of what that means is to question every assumption that you ever had about the way life is. Many indigenous people have told me the most important difference between indigenous and western ways of being is that even the most open-minded westerners perceive listening to the natural world as a metaphor rather than a literal action. Indigenous people around the world generally perceive the world as consisting of other beings to enter into relationship with and to whom we have responsibility, as opposed to resources for us to exploit.

“When I look at trees I see dollar bills.”

If you look at trees and see dollar bills, you‘re going to treat them one way. If you look at trees and see trees, you‘ll treat them another way. And if you look at this particular tree and see this particular tree, you‘ll treat them differently still. The same is true of course for women, which is one reason I am so completely opposed to pornography; when I look at women and I see orifices, I‘ll treat them one way; if I look at women and I see women I‘ll treat them another way, and if I look at this particular woman and I see this particular woman I‘ll treat her differently still.

How you perceive the world affects how you behave in the world. So, a lot of the decolonizing is to change unquestioned assumptions that control how you perceive and act in the world.

A young writer approached Anton Tschechow and said he wanted to write a story and he didn’t know what to write. So Tschechow said: “I want you to write a story about a man, who squeezes every drop of slave’s blood out of his body.”

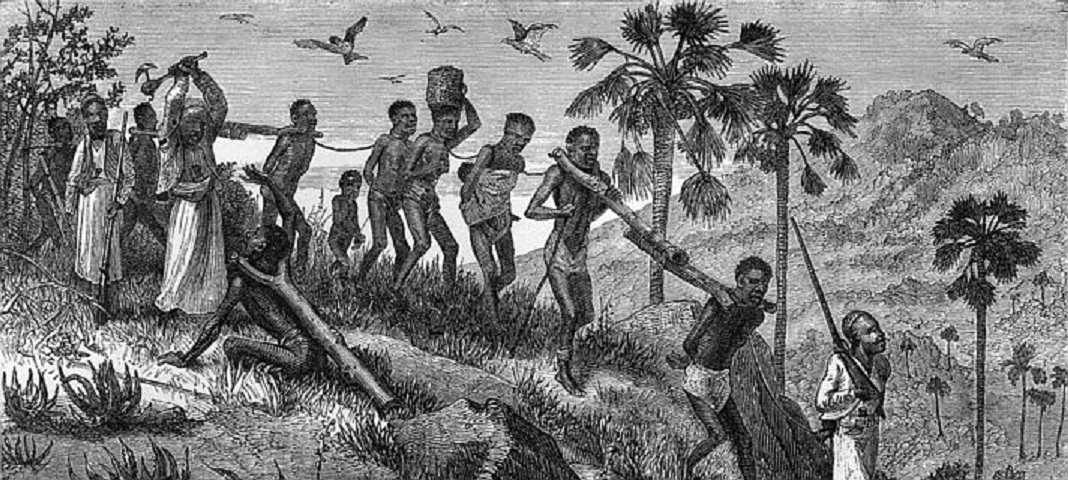

We have been trained since infancy to be slaves to the system. To be addicted to the system. The word “addict” comes from the same root as the word “edict,” and it means “to enslave.” In ancient Rome, a judge would issue an edict, that would addict someone to someone else, that would enslave them.

We are enslaved to the system, and we need to squeeze every drop of slave’s blood out of ourselves. Another way to look at this is to recognize that, as Robert J. Lifton has written about so well, before you can commit any mass atrocity you have to convince yourself that what you‘re doing is not in fact an atrocity, but instead a good thing.

So the Nazis were not committing genocide and mass murder, they were instead purifying the Aryan race. The North American settlers were not committing genocide and mass murder and land theft, they were manifesting their destiny. Today, nobody is killing the planet, they are instead developing natural resources.

I shared a stage with Ward Churchill one time and we were chatting backstage, and I said ”I can‘t believe how stupid the Nazis were to take such careful records of their atrocities, meticulous records of how much gold they pulled from teeth … why would they take such strict records of these terrible actions?” He just looked and me and said, “Derrick, what do you think the GNP is?“ GNP is a very highly detailed description of the conversion of the living to the dead, of the dismemberment of the living planet.

So part of decolonizing is to recognize that things we think are good, like civilization, like industrialism, like developing natural resources, may in fact be quite terrible and atrocious. This is absolutely crucial work. One of the things that happens through this process that is crucial to decolonizing is transfering your loyalty away from the dominant system and toward the landbase. This is pretty much what all of my work is about. Once you transfer your loyalty to the landbase, everything else is just technical, you know, what to do then. But until you do that your loyalty will still be, by definition, with the dominant culture.

When I do resistance radio interviews, I‘m always very clear before the interview that you can be as biocentric and ecocentric as you want. If we‘re talking about the Mississippi River, or talking about the Colorado River, or the Columbia River, I don‘t actually care about agriculture. My loyalty is completely with the river. If the water stays in the Colorado River, I don‘t care if that means that cotton growers will be driven out of business, or that golf courses in Arizona will go dry. Because my loyalty is not with industrial capitalism; my loyalty is with the living planet.

How do we do it? We start to question every assumption. There is a sense in which it‘s very easy and a sense in which it‘s really hard.

The sense in which it‘s very easy is that, like many environmental activists, we begin by wanting to protect a specific piece of ground. But we end up questioning the foundations of western civilization. That‘s because we start to ask questions, and once the questions start they‘ll never stop. So we can ask: why is this land being destroyed? And the answer is usually: because someone is going to make money off of it. Or economic production; it‘s good for the economy. Then you ask: why is most land harmed? Well, it‘s good for the economy.

So then you ask: have all cultures had economies based on destroying their land base? No. And then you ask: what does it mean that you have an economy based on destroying the land base? And then you ask: what is the endpoint of having an economy based on destroying the land base? And of course, the answer is obvious: you destroy the land base, and you destroy the capacity of the earth to support life. As we see.

In that sense decolonizing is really easy. All you have to do is to ask one question. It‘s the same with rape culture. You ask: why was this woman raped? Then you ask: why is any woman raped? Why are so many women raped? Has every culture been a rape culture? And once those questions start, you head back to the roots of the problem. In the case of rape, the patriarchal violation imperative, in the case of civilization, well, civilization’s economic arrangements, and also the patriarchal violation imperative.

In another sense it‘s very hard. You have to give up on everything that brought meaning before. You die, that‘s the point. That‘s a very scary process, and it can be a very painful process, it‘s a process that many of us went through in our twenties. There is that great line by Joseph Campbell: if the signs and symbols of the dominant culture work for you, then there will be a sense of meaning in your life and a sense of accord with the universe. If the signs and the symbols of Catholicism work for you, then you have a 2000 year old path of meaning laid out for you.

If the American Dream works for you, and making money brings you meaning, then you have a couple of hundred years system of meaning set out for you. I would say that meaning is really perverse, but we‘ll leave that. Campbell then says: if those signs and symbols don‘t work for you, then basically you‘ll find your life meaningless, and you‘re set adrift. Then you have to go on what he called a hero journey, and I‘m sorry for the sexism of the language. That‘s the journey, that we all have to find to go through, to find meaning in our own lives.

Life consists of a series of deaths and rebirths. It‘s pretty extraordinary that the central message of the Jesus story is completely missed. It‘s not that Jesus was a real human being who died and then was resurrected; instead it‘s that for a new part of us to be born, an old part of us has to die. This is true in any case. When we are in our late teens and early twenties, we have to die as children to be born as adults. That part is left behind, and a new part emerges. That can be incredibly painful and scary, which is why cultures around the world have had social means by which the young people would be shepherded through that process.

We don‘t have that. We certainly don‘t have any social approval for it. Instead, people are pulled back into the culture at every moment. This culture tries to bring us back through television, through books, through economically forcing you to stay in the system, making you economically dependent upon the system by telling you that you are a consumer, and not a citizen or a human animal who needs habitat. It‘s constantly reinforced. But if you can find another community, a community of people who value living trees over dollars, who value the real world, whose loyalty is with the real world, that can really help this passage.

The really difficult part of decolonizing is that it involves a great definite death and rebirth. A death of faith that the system will work out, a full internalization of the understanding that the dominant culture hates life, and that the dominant culture will kill everything on the planet unless it‘s stopped. That‘s what decolonization feels like; it‘s the death of one‘s loyalty to the system that raised you.

If space aliens had come down from out of space, and were vacuuming the oceans, changing the climate, putting dioxin in every mother‘s breast milk, obliterating the planet and giving us computers, and tomatoes in January, and whatever goodies we want; if space aliens were doing this, most of us would not have a hard time decolonizing because we would see it. But after five, and ten and fifteen generations, people won‘t see it any more.

One of the reasons we‘ve become so stupid about this is because from childhood we pledged allegiance to this culture. We were taught that this culture is more important than a living planet.

Once again, we need to think about this as though it were space aliens who were destroying the planet. Because it doesn’t really matter who is destroying the planet; they are destroying the planet and they need to be stopped.

So for me, the process of decolonizing has, as its very essence, making one‘s loyalty to the real world.