by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Nov 9, 2016 | Culture of Resistance

by Jennifer / Deep Green Resistance

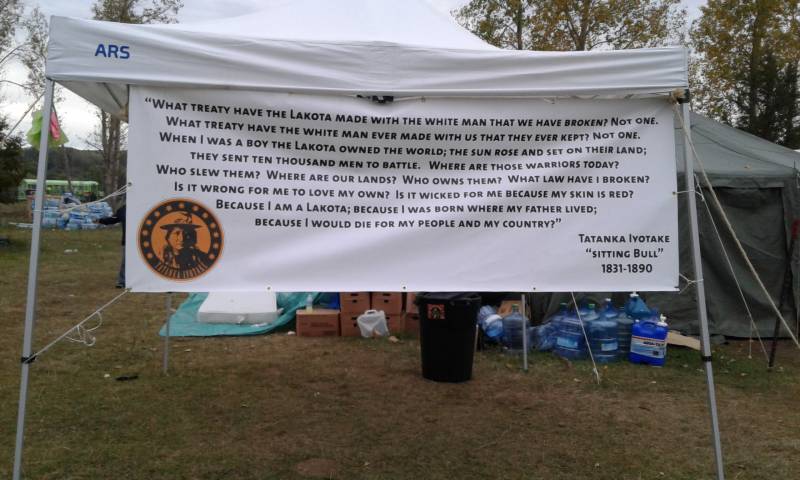

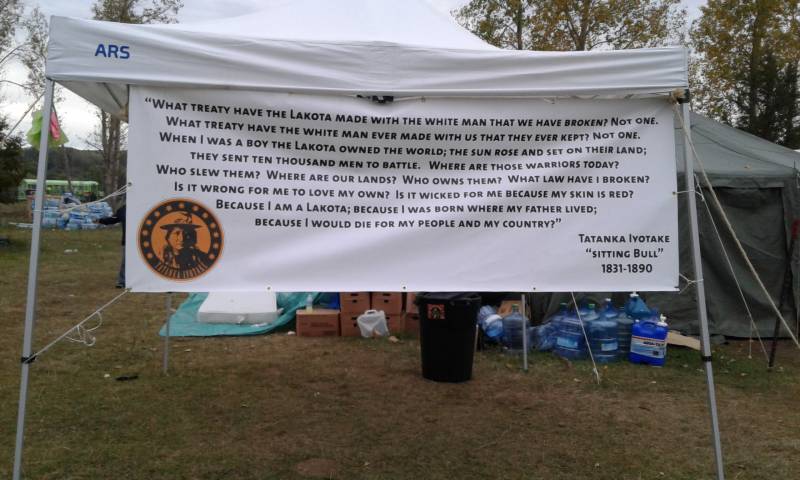

I have traveled to Standing Rock twice now. The first time was on September 16 – 20. On the first trip I went with my mother. We camped at Rosebud and spent a great deal of time in the kitchen preparing food and talking with members of the camp, indigenous and non-indigenous allies. We could hear prayers and drumming in the Oceti Sakown Camp well into the night. The atmosphere was of constant prayer and felt celebratory. There were fireworks on the first night of our stay. I visited Sacred Stone and the “Overflow,” Oceti Sakowan, camps. Between Rosebud and Sacred Stone a women’s lodge was being constructed, with the permission of the elders.

The second trip was on October 29 – November 2. I went with acquaintances and we camped in the Oceti Sakowan. We fed ourselves, and provided our own shelter. The only time I ate outside of our camp was when I went to do dishes at Rosebud. Surveillance was present on the hill overlooking the camp: flood lights, drones, plane helicopter circling. I did not take pictures. The camp itself was much quieter. I attended non violent civil disobedience training, a requirement for all new arrivals. I filled out forms with legal and prepared for the possibility of NVCD action.

I also went to an orientation for the medics. Currently a Medic tent, herbal/alternative remedy, and a body work tent have been established with a mental health group and center in formation. Meetings for the camp are held every morning and in a truly respectful and democratic manner. All voices are heard. From 2-3 hours of work a day are expected to be given to the collective. I participated in water ceremony by invitation. I gave my drum when it was asked for, to be in sweat lodge. I visited Sacred Stone, and spoke with a keeper of the sacred fire who had just returned to camp, having closed down her life a half a continent away to be at Standing Rock.

Building for the winter was well underway. Between Sacred Stone and Rosebud on the Standing Rock Reservation side of the Cannonball, the women who were building the women’s lodge had returned and were well established; the lodge was complete. Rosebud looked the same physically, but many people who I remembered had left while some remained. I had a brief conversation with a Episcopalian Minister letting me know that 300 faith leaders were answering the call to come to Standing Rock. Over 500 arrived the day after our departure.

I was physically cold, in pain, and sleep-deprived during the stay. Monday was particularly difficult and windy. Recent tests indicate I most likely have a severe form of arthritis. Fortunately be were camped by some trees and able to create a bit of a wind break. If you are planning to go, be prepared for harsh conditions and be realistic about your limitations and how to deal with them.

I have attended multiple Wednesday evening updates at Four Winds in Denver. I have learned a great deal about the legal and on-the-ground struggles, not only at Standing Rock but historically, by attending updates. These meetings have also led to engagement with an organizing group of women who coordinated Four Directions March and Prayer in solidarity with Standing Rock and on Indigenous Peoples Day (transforming Columbus Day), prayer and ceremony for Murdered and Missing Sisters, and on election day will be holding a Million Mothers March in Denver. I have been able to engage in support work by request and have been able to offer air time through WomynAir and the AM News Magazine on our local community radio station KGNU to increase awareness and notify the public when it is appropriate for them to attend.

In Conclusion: Standing Rock is a functional, resilient community of resistance. Standing Rock is prayer and ceremony and community. If there is anything that I have gathered from having been at Standing Rock it is this. Prayer and ceremony unite the people to the land, air, and water; to each other, to our ancestors, to community, to action. It is my belief, after my experience of being at Standing Rock, that this foundation gives humans the strength and sanity to face ourselves, our communities, life, and to continue to take action in defense of life. Words fail. I will continue to listen.

by DGR News Service | Oct 16, 2016 | Rape Culture

Society must choose whether women count as human

Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance

Feminism has always been a contested area of politics. Fierce arguments centre on what it is, and why we need it. The best definition I know is from Andrea Dworkin: “Feminism is the political practice of fighting male supremacy on behalf of women as a class.” In one elegant sentence, she names both the problem ― male supremacy ― and the solution ― political action.

Implicit in those 16 words are also the two requirements of the human heart: love and hope. It is an act of love to notice women. Women are on display everywhere of course ― naked, for sale, the coin of the realm in a pornographic culture ― but being an object is the opposite of being human. Noticing the harm that is being done ― insisting that it is harm ― starts from love.

Such noticing tends to have an inverse relationship to hope. When harms against a people are both vicious and everyday, hope becomes a combat discipline. But, whether grim or glad, hope is possible only because change is possible. This is the promise of feminism: as endless as the horrors seem, they could end. We, as a society, could end them.

Armed with love and hope, I travelled to London recently for a conference on male violence and how we might end it. I left the US still braced against the details that had come out of Ohio: three women, one six-year-old girl, a basement strung with chains ten years long.

I arrived in London to news of Mark Bridger’s trial: his catalogue of images of murdered girls, his library of sadistic child-porn, the stalking that escalated from online to real life. This meant real death to a perfect promise of a girl named after spring. Her parents are now condemned to a deep winter of grief; how they will survive is anyone’s guess.

Then there was the long fall of Chevonea Kendall-Bryan, the 13-year-old who fell to her death from the window of her home, having suffered sexual bullying. Longer still was the fall from human to object, through rape, and more rape, landing finally on the unyielding surface of complete public violation. Does it matter whether she jumped or fell? Her life was shattered either way.

This is where we stand or fall as a society. We will have to choose. Right now, our society is choosing to make cruelty normal. We are choosing saturation in sadism. The choice turns on whether women count as human.

A few brute facts will answer. Globally, one in three women will be raped or beaten in her lifetime. Half of all sexual assaults are committed on girls under 16: might as well start the lesson early. In the UK, a woman is raped every nine minutes. There are plenty more numbers, and inside each and every one are the broken shards where body and soul, self and world, once met.

The numbers should speak for themselves, but numbers don’t actually speak, of course. They need human voices to carry them. The result of subordination, though, is always silence. Silence is what happens when people are turned into objects. Violence will do that. Sexual violence especially will do that. Sexual violence against children is a shroud of silence that can take a lifetime to unwind.

Amnesty International reports that rape is the most traumatic form of torture. In fact, women who have survived prostitution have higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder than soldiers who have survived combat, which is to say that the war men are waging against women is in many ways worse than the wars they inflict on each other.

If you need convincing, type the word “rape” into Google images. Or, if you have the stomach and the spiritual stamina, try “torture porn”. What you will see is not entertainment, or sex, or freedom. What you will see is hell. What you will also see is that men by the million have been there before you.

We need feminism because, without it, the realities of women’s lives are unspeakable ― each woman cut adrift in a hostile, chaotic sea. Apply feminism, and that chaos snaps into a sharp pattern of subordination ― from the small, daily insults to body and soul, to the shattering traumas of incest and rape.

The crimes that men commit against women are not done to women as random individuals: they are done because women belong to a subordinate class, and they are done to keep women a subordinate class.

None of this will change unless we face the truth. I wrote above that every nine minutes a woman is raped. That is hard enough, but it is not the truth. This is: every nine minutes a man rapes a woman. And I am left with a human howl of “Why?” After 30 years spent fighting male violence and pornography, I still have no answer.

I am a feminist because I think women count as human. But feminism also insists on the humanity of men: we think that men can do better. The anthropologist Peggy Reeves Sanday studied 95 societies, and found that almost half were rape-free. It is not random. It is actually rather straightforward. Rape-free cultures value co-operation whereas rape-prone cultures reward competition. In the former, political and economic power are shared by the sexes; in the latter, women are dispossessed.

Whereas in the one, the sacred has both female and male aspects, in the other, God is only ever male. And now we come to it: in rape-free cultures, anyone can assume positions of ceremonial importance. In rape-prone cultures, men exclude women from roles of spiritual intercession.

Social subordination is like a set of concentric circles. The innermost is where the worst occurs: the cattle cars, the severed limbs, the missing girls found as bone fragments and blood stains. But every circle in the set helps to constrain the people trapped inside. The outer rings shore up the inner horrors, making them both normal and invisible.

How can such things happen, we ask in anguish? They can happen because each successive circle ― each institution and social practice ― creates the bull’s eye where Chevonea landed and April will never be found.

We have a choice, as individual men and women, and as a society. We can keep other humans barricaded inside such atrocities, or we can bring those barricades down. Either women will finally count as human, or the rancid pleasures of sadism will continue to rot our society and our souis. Choose now, before another girl falls, and another goes missing.

Originally published in the June 28, 2013 issue of Church Times

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 27, 2016 | Obstruction & Occupation

By Deep Green Resistance Seattle

A coal train entering Bellingham, Washington has been blockaded by a fossil fuel resistance group, including members of Deep Green Resistance. This blockade, part of an ongoing regional campaign against fossil fuels, has been standing strong for six hours – with no end in sight.

Beginning at four PM this afternoon, protestors erected a portable tripod structure in the middle of a rail bridge crossing Mud Bay south of Bellingham. One protester has climbed to the top and will stay until removed by police.

The organizers of the blockade say that fossil fuels must be stopped to save the planet from global warming.

When asked about her motivation for joining the resistance movement, one Deep Green Resistance member responded, “We won’t be complicit in a global catastrophe. The government and the capitalists are working together to kill the planet. We’re going to work together to stop them.”

With two refineries sitting north of town and a tar sands pipeline running underneath, Bellingham has been in the sights of the fossil fuel industry for decades. The struggle to keep fossil fuel transportation out of the small city has been ongoing. The Lummi Nation and other local resisters recently defeated plans for a major coal export terminal. However, coal merchants continue to push for the project.

The protest also delayed passenger trains, but organizers aren’t overly concerned. When asked about possible inconveniences to travelers, a protestor responded, “What’s inconvenient is losing your island to rising sea levels, or having your home flooded in Baton Rouge, or digging mass graves in Pakistan in anticipation of heat waves.” She also noted that Amtrak was notified to minimize delays in passenger transportation.

From Deep Green Resistance Seattle: http://deepgreenresistanceseattle.org/resistance/direct-action/activists-stage-coal-train-blockade-bellingham-train-stopped-5-hours-counting/

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 10, 2016 | Strategy & Analysis

Featured image by Vanessa Vanderburgh

By Joanna Pinkiewicz / Deep Green Resistance Australia

Most people in the industrial civilized world will come to a point of crisis, loosely translated from its Greek origin as: “testing time” or “an emergency event.”

An ongoing feeling of pressure, instability or a threat can all bring on such crisis. These events shake our whole being, alarm our physical bodies and rupture our rational mind. The advice for dealing with a crisis that is perceived as “personal” or “individual” often follows a set of clear, practical steps:

- Slow your breath to anchor yourself in the present

- Take a note of your emotions or bodily sensations

- Open up and express your thoughts

- Pursue a valued course of action

The last step is particularly interesting, as it suggests questioning: What do I value the most? What do I stand for? How do I want to see myself respond?

As much as a crisis brings many negatives, such as anxiety and depression, it also brings an opportunity to re-examine our lives and expand our understanding of what is happening in the world or to the world around us. It forces us to examine and to make a choice: are we going to be a bystander or are we going to become courageous in the face of a looming threat?

Research on the psychology of resistance suggests, that access to support and the right type of information is crucial to help those wanting to understand what is really happening to us and the world, as well as, what can be done to address it.

The authors of Courageous Resistance, The Power of Ordinary People list certain factors that contribute to ordinary people becoming resisters in the face of injustice or impending threat. These include a combination of:

- Preconditions: previous attitudes, experiences and internal resources

- Networks: ongoing relationships with people that offered information, resources and assistance and

- The Context itself: political climate, severity of the situation

We understand courageous resistance to be a conscious process of decision making, which is affected not only by who the decision maker is, but where they are and who they know at the particular time they become aware of a grave injustice…

We define “courageous resisters” along three dimensions: First, they are those who voluntarily engage in other-oriented, largely selfless behaviour with significantly high risk or cost to themselves or their associates. Second, their actions are the result of a conscious decision. Third, their efforts are sustained over time. [i]

Humanity today faces ongoing stress from living in the civilized world. By and large, we have managed to adapt to changes that have been imposed on us, such as higher density living and working conditions. However the escalated threat of armed violence and impending effects of climate change bring on new types of crises, which needs not only immediate response, but creation of a completely new culture. The current culture likes us to believe that the crises we are experiencing are “individual,” due to a weakness or an illness. If we choose to believe this, we are more likely to suffer from helplessness and not participate in creating this new culture.

Aric McBay explains this in Deep Green Resistance, Strategy To Save The Planet:

If someone is dissatisfied with the way society works, they say, then it is that individual’s personal emotional problem. Furthermore, the individual traumas perpetuated by those in power on individual people, on groups of people, and on the land, can seem random at first glance. But if we can trace them back to their common roots—in capitalism, in patriarchy, in civilization at large—then we can understand them as manifestations of power imbalance, and we can overcome the learned helplessness…[ii]

To begin to create a culture of resistance individuals must drop loyalty to the oppressive status quo and its systems. Two things may prevent us from fully committing to resistance: fear of punishment or separation from our kin (friends, family). While loss of “belief” in “redeeming” the existing culture is a first step towards resistance, separation from dependency on the existing systems is gradual.

As building an effective resistance culture is a long process involving generations, we must be wise at preserving our health and using our resources.

Listed below are steps that effective groups or communities follow in response to a crisis that is not personal, but wide spread and caused by either natural (earthquake, flood) or man-made circumstances (occupation, oppression, ecocide).

- Prepare: clarify our values, recruit people, gather resources, and devise the strategy

- Respond: assign roles and responsibilities, implement strategy

- Recover: extend support networks, rebuild communities, and establish new organizations

Resilience building will come from commitment and co-operation in all of those stages. After the recovery from a crisis, a group gains valuable experience and is able to refine the “emergency” response plan and train newcomers.

Experience of past resisters demonstrates rise in organisational, strategic and physical skills among individuals as well and rise in strength and independence of a group.

I am thankful for my crisis. Like a loud warning siren it told me that things are not right in the world, that I must increase my awareness and prepare for the future.

My crisis led me to discover techniques and practices that reconnected me with my body. I discovered that reconstruction of mental and physical health goes hand in hand with protecting the environment. By recognising the physical and spiritual nourishment we receive from our forests, rivers, oceans, a commitment to environmental action is born.

Taking responsibility was the first step to my healing and the beginning of an authentic life. Such path does not require perfection, but courage and imagination to create new ways of living and existing. To work as a collective in the name of all nature’s communities is a revolutionary path of resistance we desperately need today.

Deep Green Resistance is a global radical environmental organization with a strategy to address our impending planetary crisis. We have recruited capable and experienced individuals to guide and work together in implementing our strategy and fulfill our vision to dismantle the industrial civilization, assist the planet’s recovery and build sustainable communities with decentralized governance.

Join the many existing chapters or start a new one! Become a conscious resister!

Notes:

[i] Thalhammer, Kristina E.; O’Loughlin, Paula L.; Glazer, Myron Peretz; Glazer, Penina Migdal; McFarland, Sam; Shepela, Sharon Toffey; Stoltzfus, Nathan. Courageous Resistance, The Power of Ordinary People. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

[ii] McBay, Aric; Keith, Lierre; and Jensen, Derrick. Deep Green Resistance: Strategy to Save the Planet. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2011.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 6, 2016 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Education, Lobbying