by DGR News Service | Oct 29, 2017 | Listening to the Land

Featured image by Michelle McCarron

Editor’s note: This is the latest installment from Will Falk as he follows the Colorado River from headwaters to delta, before heading to court to argue for the Colorado River to be recognized as having inherent rights. More details on the lawsuit are here. The index of dispatches is here.

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance Southwest Coalition

To truly understand someone, you must begin at her birth. So, Michelle and I spent the last two days looking for the Colorado River’s headwaters in the cold and snow above La Poudre Pass on the north edge of Rocky Mountain National Park. The pass is accessible by Long Draw Road off of Colorado Highway 14. Long Draw Road is an unpaved, winding, pot-holed trek that takes you fourteen miles through pine and fir forests and past the frigid Long Draw Reservoir before ending abruptly in a willow’d flat.

We found the road covered in an inch of frosty mud which required slow speeds to avoid sliding into roadside ditches. The drive served as a preparatory period in our journey to the Colorado River’s beginnings. The road’s ruggedness and incessant bumps combined with sub-freezing temperatures to ask us if we were serious about seeing the Colorado River’s headwaters. I was worried that Michelle’s ’91 Toyota Previa might struggle up the pass, but the van continued to live up to the Previa model’s cult status.

Long Draw Road foreshadowed the violence we found at the river’s headwaters. Swathes of clearcut forests escorted the road to the pass. The Forest Service must be too lazy to remove single trees from the road as they fall because Forest Service employees had simply chainsawed every tree within fifty-yards to the left and right of the road. About 3 miles from the road’s end, we ran into a long, low dam trapping mountain run-off into Long Draw Reservoir. We expected to find wilderness in La Poudre Pass, so the dam felt like running into a wall in the dark.

The clearcuts, dam, and reservoir are grievous wounds, but none of them are as bad as the Grand Ditch. We walked a quarter-mile from the end of Long Draw Road where we found a sign marking the location of the river’s headwaters. On our way to the sign, we crossed over a 30-feet deep and 30-feet wide ditch pushing water west to east. We were on the west side of the Continental Divide where water naturally flows west. We contemplated what black magic engineers employed to achieve this feat. The ditch was as conspicuous in La Poudre Pass as a scarred-over gouge on a human face.

The Grand Ditch was begun in the late 1880s and dug by mostly Japanese crews armed with hand tools and black powder. It was built to carry water, diverted from the Colorado River’s headwaters, east to growing cities on Colorado’s Front Range. Close to two feet of swift water ran through the ditch. We learned that even before melting snowpack forms the tiny mountain streams identifiable as the Colorado River’s origins, water is stolen from her. Pausing in a half-foot of powder, I wondered whether the water stored here would end up on a Fort Collins golf course or stirred by the fins of a Vaquita porpoise in the Gulf of California.

Study the Colorado River’s birth and you’ll learn she is born from a wild womb formed by heavy winter clouds, tall mountain peaks, and snowpack. But, she emerges from this womb immediately into exploitation. In La Poudre Pass, the young Colorado River tastes the violence that will follow her the rest of her life.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by DGR News Service | Oct 25, 2017 | Listening to the Land

Featured image by Michelle McCarron

Editor’s note: This is the latest installment from Will Falk as he follows the Colorado River from headwaters to delta, before heading to court to argue for the Colorado River to be recognized as having inherent rights. More details on the lawsuit are here. The index of dispatches is here.

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance Southwest Coalition

When I agreed to serve as a “next friend” to the Colorado River in a first-ever federal lawsuit seeking personhood and rights of nature for the river, I agreed to represent the river’s interests in court. On a general level, it’s not difficult to conceptualize the Colorado River’s interests: pollution kills the river’s inhabitants, climate change threatens the snowpack that provides much of the river’s water, and dams prevent the river from flowing to the sea in the Gulf of California.

We seek personhood for the Colorado River, however, and this entails personal relationship with her. Water is one of Life’s first vernaculars and the Colorado River speaks an ancient dialect. Snowpack murmurs in the melting sun. Rare desert rain runs off willow branches to ring across lazy pools. Streams running over dappled stones sing treble while distant falls take the bass.

Personal relationship requires that you learn who the other is. Our first day in court is scheduled for Tuesday, November 14, at 10 AM [you’re invited to attend]. So, I will spend the next few weeks leading up to the court date traveling with the river, sleeping on her banks, and listening. I will ask the Colorado River who she is, and then, if she’ll tell me, I’ll ask her what she needs.

When I arrive at the United States District Court in Denver, I hope to bring the Colorado River’s answer.

(I’ll post notes from the road. And, I’m excited to be meeting up with the brilliant photographer Michelle McCarron soon.)

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Oct 19, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: The first Rights of Nature lawsuit in the US was filed on September 25, 2017, in Denver, Colorado. The full text of the complaint can be found here.

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance Great Basin

In the war for social and environmental justice, even the best lawyers rarely serve as anything more than battlefield medics.

They do what they can to stop the bleeding for the people, places, and causes suffering on the front lines, but they do not possess the weapons to return fire in any serious way. Lawyers lack effective weapons because American law functions to protect those in power from the rest of us; effective legal weapons are, quite literally, outlawed.

Nonetheless, understanding the limits of the law to affect change through my experiences as a public defender, I recently helped the Colorado River sue the State of Colorado in a first-in-the-nation lawsuit — Colorado River v. Colorado — requesting that the United States District Court in Denver recognize the river’s rights of nature. These rights include the rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and naturally evolve. To enforce these rights, the Colorado River also requests that the court grant the river “personhood” and standing to sue in American courts.

Four of my comrades in the international environmental organization Deep Green Resistance (DGR) and I, are listed as “next friends” to the Colorado River. The term “as next friends” is a legal concept that means we have signed on to the lawsuit as fiduciaries or guardians of the river. I also serve, with the brilliant Deanna Meyer, as one of DGR’s media contacts concerning the case.

Several times, I’ve been asked whether I think our case is going to win. We have provided, in the complaint we filed, the arguments the judge needs to do the right thing and rule in our favor. In this sense, I think we can win. And, if we do win, the highly endangered Colorado River will gain better protections while the environmental movement will gain a strong new legal weapon to use in defense of the natural world.

But, when has the American legal system been concerned with doing the right thing? While every ounce of my being hopes we win, if we lose, I want you to know why. I want you to be angry. And, I want you to possess an analysis that enables you to direct your anger at the proper targets.

***

The Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF) does incredible work to demonstrate how the American legal system is stacked against us. CELDF began as a traditional public interest law firm working to protect the environment. They fought against industrial projects like waste incinerators and dumps only to encounter barriers in the legal system put in place by both government and corporations.

According to CELDF, government and corporations “developed a structure of law which – rather than focused on protecting people, workers, communities, and the environment – was instead focused on endless growth, extraction, and development.” This structure is “inherently unsustainable, and has, in fact, made sustainability illegal.”

The current structure of law forces us into what CELDF calls the “Box of Allowable Activism.” The Box is formed by four legal concepts that have so far proven to be unassailable. Those concepts are state preemption, nature as property, corporate privilege, and the regulatory fallacy. State preemption removes authority from local communities by defining the legal relations between a state and its municipalities as that of a parent to a child. Local communities are not allowed to pass laws or regulations that are stricter than state law.

Currently, nature is defined as property in American law. And, anyone with title to property has the right to consume and destroy it.

As CELDF notes, “this allows the actions of a few to impact the entire ecosystem of a community.” To make this worse, corporations – who own vast tracts of nature – are granted, by American courts, corporate rights and “personhood.” Corporate personhood gives corporations the power to request enforcement of rights to free speech, freedom from search and seizure, due process and lost future profits and equal protection under the law.

Finally, CELDF explains that “the permitting process, and the regulations supposedly enforced by regulatory agencies, are intended to create a sense of protection and objective oversight.” But, while water continues to be polluted, air poisoned, and the collapse of every major ecosystem on the continent intensifying, we must conclude that this protection is not happening.

Regulatory agencies give permits. By definition, they provide permission to destructive activities. CELDF states, “When they issue permits, they give cover to the applicant against liability to the community for the legalized harm.”

***

I went to law school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and became a public defender in Kenosha, WI because I thought I could push back against the institutional racism of the American criminal justice system. Just like CELDF learned working through traditional environmental law, I learned quickly that my hands were tied by the legal structure, too.

Something similar to CELDF’s “Box of Allowable Activism” exists in criminal law. Prosecutors overcharge. For example, I represented a single mother of three charged with six counts of theft despite the total value of what she was accused of stealing amounting to less than $30 — one count for the bag of rice, one for the butter, one for the salt, one for the pack of chicken breasts, one for the onion, and one for the garlic.

Then, prosecutors offer plea deals taking advantage of a defendant’s rational self-interest and fear. In my previous example, the prosecutor offered to dismiss four of the six counts of theft and recommend 30 days in jail if my client pled guilty to two counts, the rice and chicken. When the prosecutor made her offer, she reminded my client that not taking the deal meant facing a long trial process while risking conviction on all six counts and being exposed to two years in jail.

Defense attorneys are ethically bound to defer to their clients’ desire to take a plea deal. Meanwhile, public defender offices are woefully underfunded. And, with the majority of criminal defendants so poor they qualify for court-appointed counsel, public defenders are notoriously overworked producing mistakes that lead to their clients’ incarceration.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Deep ecologist, Neil Evernden, connects the problems facing lawyers fighting institutional racism and lawyers fighting ecocide in his book “The Natural Alien: Humankind and Environment.” Evernden asks us to imagine we are lawyers defending a client who is black in apartheid South Africa or the Jim Crow American south.

He asks, “What would you do if faced with a trial judge who denies your client any rights and who, after hearing your case, simply says: ‘So what — is he white?’”

Everndem claims that we only have two options in this situation. We can demand that the judge recognize the rights and dignity of our client and risk condemning our client to execution. Or, we can play by the rules, reinforce problematic law, contribute to its precedence, and detail our client’s genealogical records at length “to try to prove our client white.”

Evernden correctly notes that too often when environmentalists are challenged to justify their declarations on behalf of the living world, they proceed to try to prove their client white. Evernden writes, “Rather than challenge the astonishing assumption that only utility to industrialized society can justify the existence of anything on the planet” the environmentalist “tries to invent uses for everything.” But, “the only defense that can conceivably succeed in the face of this prejudice is one based on the intrinsic worth of life, of human beings, of living beings, ultimately of Being itself.”

We want our lawsuit, specifically, and the rights of nature framework, generally, to be legal arguments for the intrinsic worth of life and of living beings like the Colorado River.

We are attacking two of the walls forming the Box of Allowable Activism. We seek to overturn the concept that nature is only property, and we seek to erode corporate power by giving the source of corporate power (nature) rights to stop corporate exploitation. These arguments are not currently accepted, but neither was the argument that “separate is inherently unequal” when Thurgood Marshall argued this and ended school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education.

This is all well and good, but we are still forced to construct our argument only with currently acceptable legal language. We seek “personhood” for the Colorado River, for example. But, the river is much more than a person. The river is an ancient and magnificent being who carved the Grand Canyon, who braved some of the world’s most arid deserts on her path from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California, and who facilitates countless lives, human and nonhuman.

I am afraid, that in seeking personhood for the Colorado River, people will mistake our arguments as trying to prove the Colorado River a “person” while reinforcing the notion that a being only has value as far as that being resembles a human.

***

Evernden only contemplated two options. We can prove the Colorado River a person, or we can demand recognition of our client’s dignity. But, there is a third option: Dismantle the power stacking the legal system against communities and natural ecosystems.

To fight this power, we must understand how power works. Dr. Gene Sharp, who CNN has called “a dictator’s worst nightmare” and the “father of nonviolent struggle,” is the world’s leading theorist of power.

Sharp identifies two manifestations of power – social and political. Social power is “the totality of all influences and pressures which can be used and applied to groups of people, either to attempt to control the behavior of others directly or indirectly.” Political power is “the total authority, influence, pressure, and coercion which may be applied to achieve or prevent the implementation of the wishes of the power-holder.”

Sharp lists six sources of power: authority, human resources, skills and knowledge, intangible factors, material resources, and sanctions. Interfering with these sources of power is the key to a successful resistance movement.

The powerful know where their power comes from and they protect the sources of their power. It is one thing to protect these sources with brute force. But, why use brute force when you can persuade the oppressed that there is nothing they can do to affect the sources of power? Or, when you can mislead the oppressed about where those sources of power are?

In this spirit, the powerful do everything they can to convince the oppressed that the current arrangement of power is inevitable. They seek to convince us that the legal system exists to protect communities and the environment. They teach us to look back through history to view our few victories as the result of a system devoted to justice.

These few victories are held up as proof that sooner or later the courts always make the right decision. We are pacified with assurances that if our lawyers are clever enough, if they work hard enough, if they articulate the truth eloquently enough, judges will recognize the brilliance of our lawyers’ arguments and justice will be served.

Justice for the natural world has rarely been served. CELDF names the final blockade to justice the “Black Hole of Doubt” and teaches, “We think we’re not smart enough, strong enough, or empowered enough – we literally do not believe we have the inalienable right to govern.” Sharp says, “Power, in reality, is fragile, always dependent for its strength and existence upon a replenishment of its sources by the cooperation of a multitude of institutions and people – cooperation which may or may not continue.”

Any resistance movement aspiring to true success must engage in shrewd target selection to undermine sources of power. Taking Sharp a step further, it is possible to prioritize which sources are more essential to the functioning of power than others. Corporate power is maintained through the exploitation of the natural world. There is no profit without material products. There are no material products without the natural world. If corporations lose access to ecosystems like the Colorado River, they will fail. If corporations fail, they can no longer control our system of law.

We may win in court and corporations will have to respect the Colorado River’s rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and naturally evolve. We will also gain a foothold for other ecosystems to assert their own rights. We may fail in court, but that does not mean the fight is over.

In many ways, our failure would simply confirm what we already know: the legal system protects corporations from the outage of injured citizens and ensures environmental destruction. If we fail, we must remember there are other means — outside the legal system — to stop exploitation.

Regardless of what happens in our case, we encourage others to employ whatever means they possess to protect the natural world who gives us life.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 25, 2017 | Lobbying, Strategy & Analysis

Featured image: Dead Horse Point, Colorado River. (Clément Bardot/Wikimedia/CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Editor’s note: The first Rights of Nature lawsuit in the US was filed on September 25, 2017, in Denver, Colorado. The full text of the complaint can be found here.

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

On Tuesday, September 26, the Colorado River will sue the State of Colorado in a first-in-the-nation lawsuit requesting that the United States District Court in Denver recognize the river’s rights of nature. These rights include the rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and naturally evolve. To enforce these rights, the Colorado River will also request that the court grant the river “personhood” and standing to sue in American courts.

Four of my comrades in the international environmental organization Deep Green Resistance and I, are serving as “next friends” to the Colorado River. We are represented by the noted civil rights attorney Jason Flores-Williams who is based in Denver. Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund is serving as advisors in the case.

The term “as next friends” is a legal concept that means we have signed on to the lawsuit as fiduciaries or guardians of the river. Under current law, the Colorado River is not “legally competent” and, so needs “next friends” to ensure her rights are protected. A “next friend” is someone who appears in court in place of another who is not competent to do so – like a minor or someone with a mental disability. My role, as next friend to the Colorado River, is to protect the river’s rights.

We recently released a press release that has been widely shared on social media. National media outlets are beginning to take notice. And, we’re getting interviews, receiving email inquiries, and responding to online comments. So far, the most common question is: Why does the Colorado River need rights?

************

The most fearless environmental philosophers – thinkers like Susan Griffin, Neil Evernden, Derrick Jensen, and John Livingston – have insisted that we will never be safe so long as the natural world we depend on is objectified and valued only for the way humans use it. Livingston calls the objectification of nature “resourcism” and explains: “A ‘resource’ is anything that can be put to human use … It is the concept of ‘resource’ that allows us to perceive nature as our subsidiary.” Livingston notes that once the nonhuman “is perceived as having some utility – any utility – and is thus perceived as a ‘resource,’ its depletion is only a matter of time.”

Because our legal system currently defines nature as property, “resourcism” is institutionalized in American law. While climate change worsens, water continues to be polluted, and the collapse of every major ecosystem on the continent intensifies, we must conclude that our system of law fails to protect the natural world and fails to protect the human and nonhuman communities who depend on it.

Jensen, while diagnosing widespread ecocide, observes a fundamental psychological principle: “We act according to the way we experience the world. We experience the world according to how we perceive it. We perceive it the way we have been taught.” Jensen quotes a Canadian lumberman who once said, “When I look at trees I see dollar bills.”

The lumberman’s words represent the dominant culture’s view of the natural world. Jensen explains the psychology of this objectification, “If, when you look at trees you see dollar bills, you will act a certain way. If, when you look at trees, you see trees you will act a different way. If, when you look at this tree right here you see this tree right here, you will act differently still.”

Law shapes our experience of the world. Currently, law teaches that nature is property, an object, or a resource to use. This entrenches a worldview that encourages environmental destruction. In other words, when law teaches us to see the Colorado River as dollar bills, as simple gallons of water, as an abstract percentage to be allocated, it is no wonder that corporations like Nestle can gain the right to run plastic bottling operations that drain anywhere from 250 million to 510 million gallons of Colorado River water per year.

The American legal system can take a good step toward protecting us all – human and nonhuman alike – by granting ecosystems like the Colorado River rights and allowing communities to sue on these ecosystems’ behalf. When standing is recognized on behalf of ecosystems themselves, environmental law will reflect a conception of legal “causation” that is more friendly to the natural world than it is to the corporations destroying the natural world. At a time when the effects of technology are outpacing science’s capacity to research these effects, injured individuals and communities often have difficulty proving that corporate actions are the cause of their injuries. When ecosystems, like the Colorado River, are granted the rights to exist, flourish, regenerate, and naturally evolve, the obsolete causation theory, en vogue, will be corrected.

************

American history is haunted by notorious failures to afford rights to those who always deserved them. Americans will forever shudder, for example, at Chief Justice Roger Taney’s words, when the Supreme Court, in 1857, ruled persons of African descent cannot be, nor were never intended to be, citizens under the Constitution in Dred Scott v. Sanford. Justice Taney wrote of African Americans, “They had for more than a century before been regarded as being of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race … and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect…” And, of course, without rights that white, slave-owning men were bound to respect, the horrors of slavery continued.

The most hopeful moments in American history, on the other hand, have occurred when the oppressed have demanded and were granted their rights in American courts. Despite centuries of treating African Americans as less than human while defining them as property, our system of law now gives the same rights to African Americans that American citizens have always enjoyed. Once property, African Americans are now persons under the law. Similarly, despite a centuries-old tradition where women were, in the legal sense, owned by men, our system of law now gives the same rights to women that American citizens have always enjoyed. Once property, women are now a person under the law.

It’s tempting to describe this history as “inevitable progress” or as “the legal system correcting itself” or with some other congratulatory language. But, this glosses over the violent struggles it took for rights to be won. The truth is, and we see this clearly in Justice Taney’s words, the American legal system resisted justice until change was forced upon it. It took four centuries of genocide and the nation’s bloodiest civil war before our system of law recognized the rights of African Americans. While the courts resisted, African Americans were enslaved, exploited, and killed.

Right now, the natural world is struggling violently for its survival. We watch hurricanes, exacerbated by human-induced climate change, rock coastal communities. We choke through wildfires, also exacerbated by human-induced climate change, sweeping across the West. We feel the Colorado River’s thirst as overdraw and drought dries it up. It is the time that American law stop resisting. Our system of law must change to reflect ecological reality.

************

Colorado River between Marble Canyon (Source: Alex Proimos/Flickr/CC-BY-NC-2.0)

This is ecological reality: all life depends on clean water, breathable air, healthy soil, a habitable climate, and complex relationships formed by living creatures in natural communities. Water is life and in the arid American Southwest, no natural community is more responsible for the facilitation of life than the Colorado River. Because so much life depends on her, the needs of the Colorado River are primary. Social morality must emerge from a humble understanding of this reality. Law is integral to any society’s morality, so law must emerge from this understanding, too.

Human language lacks the complexity to adequately describe the Colorado River and any attempt to account for the sheer amount of life she supports will necessarily be arbitrary. Nevertheless, many creatures of feather, fin, and fur rely on the Colorado River. Iconic, and endangered or threatened, birds like the bald eagle, greater sage grouse, Gunnison sage grouse, peregrine falcon, yellow-billed cuckoo, summer tanager, and southwestern willow flycatcher make their homes in the Colorado River watershed. Fourteen endemic fish species swim the river’s currents including four fish that are now endangered: the humpback chub, Colorado pikeminnow, razorback sucker, and bonytail.

Many of the West’s most recognizable mammals depend on the Colorado River for water and to sustain adequate food sources. Gray wolves, grizzly bear, black bear, mountain lions, coyotes, and lynx walk the river’s banks. Elk, mule deer, and bighorn sheep live in her forests. Beavers, river otters, and muskrats live directly in the river’s flow as well as in streams and creeks throughout the Colorado River basin.

The Colorado River provides water for close to 40 million people and irrigates nearly 4 million acres of American and Mexican cropland. Agriculture uses the vast majority of the river’s water. In 2012, 78% of the Colorado’s water was used for agriculture alone. 45% of the water is diverted from the Colorado River basin which spells disaster for basin ecosystems. Major cities that rely on these trans-basin diversions include Denver, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Salt Lake City.

Despite the Colorado River’s importance to life, she is being destroyed. Before the construction of dams and large-scale diversion, the Colorado flowed 1,450 miles into the Pacific Ocean near Sonora, Mexico. The river’s life story is an epic saga of strength, determination, and the will to deliver her waters to the communities who need them. Across those 1,450 miles, she softened mountainsides, carved through red rock, and braved the deserts who sought to exhaust her.

Now, however, the Colorado River suffers under a set of laws, court decrees, and multi-state compacts that are collectively known as the “Law of the River.” The Law of the River allows humans to take more water from the river than actually exists. Granting the river the rights we seek for her would help the courts revise problematic laws.

The regulations set forth in the 1922 Colorado River Compact are the most important and, perhaps, the most problematic. Seven states (Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming) are allotted water under the Compact. When the Compact was enacted, the parties assumed that the river’s flow would remain at a reliable 17 million acre-feet of water per year and divided the water using a 15-million acre feet per year standard. But, hydrologists now know 17 million acre-feet represented an unusually high flow and was a mistake. Records show that the Colorado River’s flow was only 9 million acre-feet in 1902, for example. From 2000-2016, the river’s flow only averaged 12.4 million acre-feet per year. So, for the last 16 years, the Compact states have been legally allowed to use water that isn’t there.

“Use it or lose it” laws are also common throughout the Colorado River basin. These laws threaten ranchers, farmers, and governments holding water rights who use less water than they are legally entitled to with seeing their allotments cut. So, those with water rights are encouraged to trap or use more water than they need.

Since the completion of the Glen Canyon Dam in 1963, the Colorado River has rarely connected with the sea. Stop and let that sink in. Many scientists believe the river is between 4 and 6.5 million years old. The Colorado River is so strong, so determined, she cut out the Grand Canyon. This magnificent being, millions of years old, who formed the Grand Canyon is being strangled to death by dams, climate change, overallocation, and a legal system that refuses to remedy its own insanity.

************

When you contemplate all those who depend on the Colorado River when you know the sheer quantity of life the river sustains, is it possible to mistake her inherent value?

I hate to reduce a being so ancient and so powerful to an argument based in human self-interest. Know this: If you’re one of the 40 million Americans who depend on the Colorado River’s water and you’re hydrated right now, the river is literally part of you. If that water is poisoned, if that water dries up, if corporate rights to steal that water and sell it back to you continue to trump the river’s right to exist, you will be hurt. This is not law. This not rhetoric. This is reality.

This is also why the Colorado River needs rights. Life requires clean water, breathable air, healthy soil and a habitable climate to create healthy ecosystems. Without these ecosystems, life is impossible and the right to life is meaningless. American law fails to protect life’s requirements because it defines nature as property and does not recognize the rights of nature. In a rights-based system of law, to be without rights is to be defenseless. And, after witnessing centuries of the exploitation of the natural world, we know that to be defenseless is to ultimately be destroyed. It’s time we protect those, like the Colorado River, who give us life.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 22, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: This is the third installment in a multi-part series. Browse the New Park City Witness index to read more.

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

Author’s Note: A member of Park City’s city government recently asked me why I write about Park City when Park City is doing so much for the environment, compared to other communities. I hope my respect for this person and the question is reflected in the days I spent contemplating an answer. In order to answer this question, I must answer several related questions. These answers give me a chance to be transparent about my motivations for writing this New Park City Witness series.

Underlying the question “Why do I write about Park City?” is the question “Why do I write at all?”

One reason I write is reflected in an experience I had, a few days ago, in Summit Land Conservancy’s offices. On a shelf, in a conference room, a book’s plain green and white cover grabbed my attention. It was the first edition of Park City Witness, published in 1998. Having recently finished the second edition of Park City Witness, and learning the first was long out of print, I was excited to see an original copy. I asked Summit Land Conservancy executive director Cheryl Fox if I could borrow the book.

Books, as anyone who has read a few knows, have the power to choose their readers. While reading the preface to the first Park City Witness, I knew I had been chosen. Maybe Cheryl knew I needed to read the book, too, because she wrote the preface to the first Park City Witness. In this preface, she quoted author Stephen Trimble who, in 1997 “speaking to a collection of writers and slow-growth activists amid the crowded shelves of Dolly’s Bookstore…explained how important it is for people who can write to write.”

Twenty years later, and Trimble’s words feel like they were spoken directly to me. I can write and because I can write, it is important for me to write.

If it’s important for people who can write to write, it’s even more important for people who can write to write what needs to be read. While nearly two hundred species go extinct daily, while every mother’s breastmilk contains known carcinogens, while every major biosphere on Earth collapses around us, does anything need to be read more than encouragement for stopping the destruction?

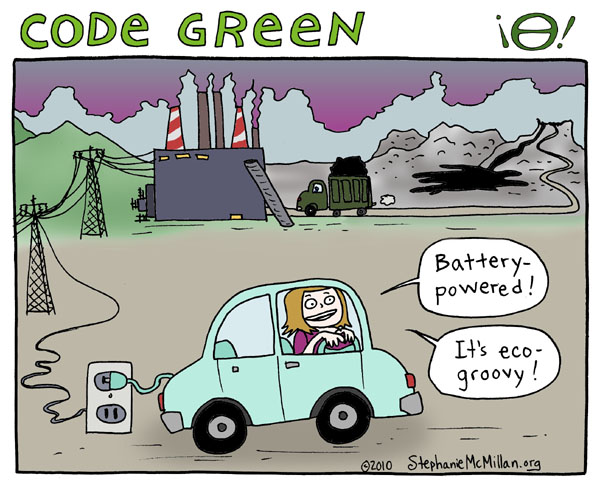

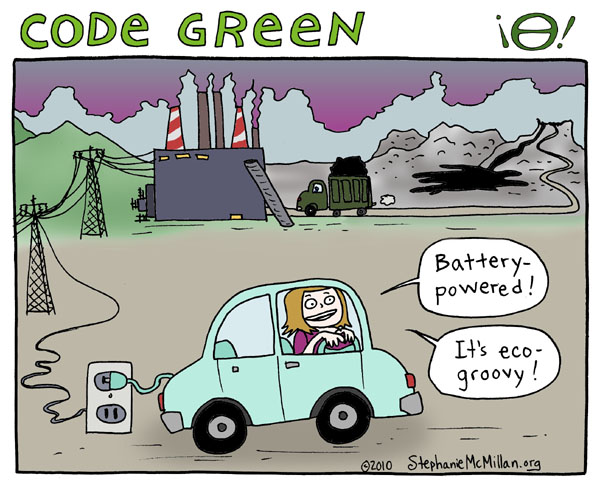

I think the answer is obviously no. Many artists share this feeling. My favorite political cartoonist, Stephanie McMillan, in an essay titled “Artists: Raise Your Weapons” writes “…in times like these, for an artist not to devote her/his talents and energies to creating cultural weapons of resistance is a betrayal of the worst magnitude, a gesture of contempt against life itself. It is unforgivable.”

Derrick Jensen, reflecting on a decades-long writing career with over twenty published books, writes, “…if we judge my work, or anyone’s work, by the most important standard of all, and in fact the only standard that really matters, which is the health of the planet, my work (and everyone else’s) is a complete failure. Because my work hasn’t stopped the murder of the planet.”

***

I write about Park City because of the privilege and power that exist here.

It may or may not be true that Park City does more than other communities to protect the environment. We must remember that Park City’s human population depends on an ecologically unnecessary and problematic industry – tourism – for its continued existence. Ask yourself: Do corporate marketers spend millions of dollars on enticing hundreds of thousands of people to board greenhouse gas emitting planes from around the world to visit… Kamas? Are tons of coal burned to pump hundreds of millions of gallons of water up mountainsides to snow-making machines in…Heber?

There’s a sense in which it really doesn’t matter whether Park City is doing more than other communities. My almost-five-year-old niece is becoming notorious for her sassy one-liners and refusing to let adults get away with their bullshit. I shudder when I think about looking her in the eye when she’s my age. She’s not going to care if Park City did more than other communities to stop the destruction of the world. She’s going to care that she can raise children in a world with clean water, clean air, and a habitable climate. She’s going to care, if she does have a baby, that she can feed her baby without passing carcinogens through her breastmilk to her baby.

I write about Park City because it doesn’t matter which community is more environmentally-friendly. The only thing that matters, while life on earth collapses, is stopping the collapse. Stopping the collapse will require confrontation with those in power and this confrontation will require material resources. Close to 80% of Park City’s population is white and white people benefit the most from the exploitation of the natural world. People of color, around the world, have long formed the frontlines of the environmental movement. Justice demands that white people join them there. Similarly, the median property value in Park City is $868,100, and the median household income is $105,000, which is almost double the national average. Park City has more than most communities, so Park City should give more than most communities.

***

The most important reason I write is because I’m in love. I’m in love with Gambel oak, maple, and aspen. I’m in love with the way they offer one last display of visual ecstasy in their changing colors before sleeping for the winter. I’m in love with rain and snow, the mystical moment rain becomes snow on a northerly autumn wind, and the water both of them bring. I’m in love with my partner, who was born here. I’m in love with her big, gorgeous brown eyes. I’m in love with the way her eyes become even bigger with warmth when she hears joy in her loved ones’ voices.

In short, I’m in love with life – a life made possible by Park City’s natural communities. We may experience life because the water we drink here, the air we breathe here, and the food we eat here combine to give us physical bodies. To love life is to love our bodies and loving our bodies, we must listen to them.

My body tells me to write. If I go more than a few days without pen, notebook, and solitude, the physical symptoms of anxiety affect me. I become fidgety, easily distracted, and slightly sick to my stomach. The longer I go without writing something coherent, the worse these symptoms get.

My body speaks through these symptoms. Through fidgetiness, my body tells me to act; writing, after all, is an action. The troubles with concentration are a warning to use my focus or lose it. Nausea accompanies and symbolizes the writing process, for me. There are times I’ve tried to quit writing, tried to shirk the hours of rumination, research, and drafting. But, the best words are not mine. They are given to me. Unreleased, they pool like bile and there is no relief until they’re written.

I used to be embarrassed to admit that I write to feel better. This seemed selfish to me. It felt impure. But, now I know that I do not create the anxiety anymore than I create the swelling that accompanies rolling an ankle. The swelling is a gift, a gift from my body, from the forces of life creating my body. My body, through swelling, tells me not to walk on the rolled ankle, and tells me to let the ankle heal.

Wherever we look there are bodies swelling, wounded, and scarred. Forests are clearcut, rivers no longer flow to the sea, and canyons are flooded by reservoirs. Life speaks through bodies – ours’, forests’, rivers’, canyons’ and so many more. Life tells us to let these bodies heal.

Before healing can take place, the injury must be stopped. Life, everywhere, is being injured. It does not matter how we stop the injury. But, we must stop it. There are a growing number of us in Park City who are willing to do more than is currently being done. We are willing to place our bodies in front of those destroying the planet – bodies we love as much as you love yours. Many of us are young, lack the wealth of older generations, look at a future growing darker and darker, and say, “This must stop.”

We could use your help.