by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 8, 2017 | Human Supremacy

Featured image: Bonanza Flats

Editor’s note: This is the second installment in a multi-part series. Browse the New Park City Witness index to read more.

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

Before murdering millions during the Holocaust, the Nazis referred to Jews as rats. After murdering 17 people and lobotomizing some of his victims in an attempt to preserve them, alive but in a catatonic state, serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer explained, “…I tried to create living zombies…I just wanted to have the person under my complete control, not having to consider their wishes, being able to keep them there as long as I wanted.” In vivisection labs, scientists commonly cut animals’ vocal cords, so the scientists don’t have to listen to the animals scream.

These examples illustrate a common psychological phenomenon: In order to commit atrocities, humans characterize their victims as sub-human, objectify and silence them. It is, after all, much easier to destroy the less than human and the voiceless.

Civilized humans are currently destroying the natural world. Water continues to be polluted, air is poisoned, soil is lost faster than it can be replaced, and the collapse of every major biosphere across the planet intensifies. This destruction is made possible through the objectification and silencing of the natural world. The American legal system defines nature as property. Capitalism calls nonhumans “natural resources” and only values them as profits. The Abrahamic religions remove the sacred from the natural world and give it to an abstract, patriarchal God who somehow exists beyond the natural world.

It’s no wonder, then, that many in Park City participate in the silencing of nature, too. Many Parkites, for example, celebrate the existence of thousands of acres of land designated as “protected open space.”

There are several problems with this. First, the term “open space” is dishonest and works to objectify nonhumans while silencing the natural world. Objectification and silencing pave the way for exploitation. Second, as long as runaway climate change threatens snowfall, creates droughts, and contributes to wildfire intensity, no natural community in Park City can truly be considered “protected.” To call endangered natural communities protected leads to complacency, and we cannot afford complacency while the world burns.

The “Save Bonanza Flats” Campaign, which raised $38 million to protect 1,350 acres of high-altitude land from development, was a beautiful expression of the community’s love for life. Do not mistake me, I am deeply glad that Bonanza Flats is safe from hotels and multi-million dollar homes. But, Bonanza Flats is not safe, and will never be safe, as long as the dominant culture’s insatiable appetite for destruction is ensured by humans who believe the natural world is nothing more than lifeless matter for humans to use.

***

While working on this essay, I decided to head up Guardsman Pass to ask those who live in Bonanza Flats what they think about “protected open space.” Hiking is contemplative for me. I was asking myself just how, exactly, I thought the nonhumans in Bonanza Flats would express their feelings about being “open space” when I rounded a bend to find myself face to face with a bull and cow moose grazing among the aspen.

The aspen were mature, many of them boasting trunks eighteen and twenty-four inches in diameter. They grew closely together, creating an ancient silvan atmosphere with dappling silvers, golds, and greens. The afternoon sunshine mixed with aspen leaves to give me the slight, pleasant sense of existential vertigo that accompanies the timelessness of life’s original joys.

I met the bull moose’s gaze. My bones recognized their nearness to a greater collection of their kindred. My muscles, observing the moose’s, remembered their first purpose and tingled with excitement. His eyes, browns in brown, reflected all the different woods he’d ever strode through. I’m not sure how long we considered each other, but when he finally looked away, his wisdom was undeniable.

And, I had my first answer: To share an aspen grove with a bull moose in Bonanza Flats, is to know this space is anything but open.

I continued on to find a stone to sit on and watched the lazy orange flutter of butterfly wings. I listened to the soft hum of bees, the breeze through quaking aspen leaves, and the hypnotic click of grasshoppers in flight. I saw mule deer bounding over a fence, a red-tailed hawk riding wind pockets, and squirrels tossing pine cones to the ground, narrowly missing human heads (for the squirrels’ winter caches). All these beings confirmed the lesson the bull moose taught me. Bonanza Flats is not open, it is filled with countless living beings.

An approaching rain cloud brought tidings of the radical interconnectedness of all life and proved that Bonanza Flats is not truly protected. When the cloud arrived to give its water, the rain evaporated well before it reached us. I was reminded that Bonanza Flats, like all communities along the Wasatch Range, depend on snowpack for life-giving water. Simple arithmetic tells us that as long as total snowpack diminishes decade after decade, as it has been since the 1950s, sooner or later there won’t be enough water left.

While Bonanza Flats is safe from the developers’ bulldozers and chainsaws, many threats, just as deadly, still exist. Marssonina fungus spores, aided by climate change, could spread over aspen leaves until they no longer quake. Shorter winters allow the tiny pricks of too many tick bites to suck moose lives away. The worrisome scent of wildfire smoke haunts the wind. And, the asthmatic cough of children brought to the mountains by their parents to escape the Salt Lake Valley’s terrible air quality ring across Bonanza Flats’ trails.

***

Not all humans have objectified and silenced the natural world. For the vast majority of human history, humans lived in balance with the natural world we depend on. We lived in this way, in part, because we developed cultures that taught the sacredness of the natural world.

I’m writing this from the eastern edge of the Great Basin where the Western Shoshone, Paiute, Goshute, Washo and others lived sustainably for millennia. Much of my work in the region has been to protect pinyon-juniper forests from government-sponsored clearcuts. The forests make poor livestock grazing and ranchers make more money when the forests are replaced with grasses, so the forests are demonized. And, just like the demonization of Jews led to the Holocaust, the demonization of pinyon-juniper forests leads to millions of acres of clear-cuts.

Food from pinyon pine nuts and medicine from juniper trees were staples in many of the Great Basin’s traditional cultures. Pine nuts and juniper berries can be harvested without damaging the forests, so native peoples lived on what the land freely gave. In my research, I stumbled upon the transcript of a presentation[1] Glenn E. Wasson, a Western Shoshone man, gave at a pinyon-juniper conference hosted by the University of Nevada-Reno, the United States Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management. His words describe his people’s spirituality and represent a healthy relationship with the natural world.

Wasson said, “Each living entity constitutes a link in the chain of life. All those seen and unseen, all who grow from the ground, all those who crawl, all those who swim, all those who walk on legs, all those who fly, are all intertwined in the chain of life. Each plays a vital role in the keeping of a strong, healthy, and living Mother Earth, who provides each and every entity with all the necessities for life.” Contrast Wasson’s worldview with the dominant culture’s conception of nature as property, as resources, as objects and we begin to see why we’re in the mess we’re in.

While criticizing the Forest Service and BLM’s treatment of pinyon-juniper forests, Wasson described the mindset all of us must embrace. He said “…the cutting down of a single living tree is sacrilegious – the cutting down of a forest – UNTHINKABLE!” Until we begin to see individual nonhumans as sacred and natural communities worthy of our utmost respect, the destruction will continue.

Simply changing our language will not stop the destruction and I am not criticizing anyone’s efforts to protect Bonanza Flats from development. We need much more than better words and any land that stands free of development today, has a chance to stand free of development tomorrow. Land developed today may take decades to recover.

It’s not just Bonanza Flats. Park City boasts 8,000 acres of so-called protected open space. These are not protected open spaces. These are living natural communities where countless nonhumans live with lives as valuable to them as yours is to you. And, their lives are under attack.

I’m not writing anything you don’t already know. Most people in Park City are concerned about the natural world. Unfortunately, it appears that most Parkites are more interested in using the natural world, than in saving it. Why do I say this? Well, ask yourself, do most people in Park City spend more time confronting the forces destroying snow, or more time skiing on it? Do most people spend more time working to protect threatened Canada lynx, or more time mountain biking through Canada lynx’ homes? Do most people spend more time trying to save Colorado Pikeminnows, or more time flying fishing the waters Colorado Pikeminnows swim through?

There’s nothing wrong with enjoying the natural world. But, nonhumans do not exist for human enjoyment, they exist for themselves. It is only through centuries of cultural conditioning, teaching us to see the natural world as full of objects for our use, that some humans find nothing wrong with spending more time riding bikes than fighting for our nonhuman kin.

Life is created by complex collections of relationships formed by living creatures in natural communities. Water, air, soil, climate, and the food we eat depend on natural communities. The needs of these communities are primary; morality, the efforts of our daily lives, and our cultural teachings must emerge from a humble relationship with these natural communities. True sustainability is impossible without this.

Not long ago, all humans lived in humble relationships with natural communities. We developed traditional cultures that were rooted in the connectedness of all living beings. These cultures insisted upon the inherent worth of the natural communities who gave us life. Members of these cultures did not know “open spaces,” they knew places filled with those who grow from the ground, those who crawl, those who swim, those who walk on legs, and those who fly.

The dominance of a culture that objectifies and silences nature and calls natural communities “open space” enables its destruction. This culture has pushed the planet to the verge of total collapse. To avert collapse, the destruction must stop. We must create cultures where the exploitation of individual nonhumans is sacrilegious, and wholesale environmental destruction is unthinkable. We must stand in solidarity with all those – human and nonhuman – who share this living community we call Park City.

[1]Wassen, G.E. 1987. The American Indian response to the pinyon-juniper conference. In: Everett, R.L., comp. Proceedings: Pinyon-juniper conference. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-GTR-215. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: 38-41.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 22, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

Editor’s note: This is the first installment in a multi-part series. Browse the New Park City Witness index to read more.

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

In Park City, the task is clear: Stop climate change, or the snow stops. Snowpack is the region’s freshwater supply and water is life. So, stop climate change or the community will lose life.

This is not news to most Parkites. And, thankfully, many Parkites have taken, at least, some kind of action. Park City Municipal Corporation hopes to achieve carbon neutrality, for the whole community, by 2032. An electric bike program was recently introduced, and electric city busses now run routes through town, in an effort to reduce carbon emissions. In a truly amazing display of community generosity, $38 million was raised to protect Bonanza Flats from development.

Meanwhile, there are a growing number of us in Park City, and across the country, who have lost faith in the traditional tactics employed by the environmental movement for creating change.

We voted. Many of us helped Barack Obama gain the presidency only to see American natural gas production increase by 34% and crude oil production increase by 88% since George W. Bush’s final year in office. Our votes couldn’t stop Donald Trump from gaining the presidency and everyday brings more news of his insanity. The EPA is gutted. The United States pulled out of the Paris Climate Accord. And, climate change deniers occupy many of the federal government’s most powerful positions.

We reduced, reused, and recycled. Then, we learned that the general consensus amongst climate scientists is that developed nations must reduce greenhouse gas emissions 80% below 1990 levels by 2050 to avoid runaway climate change. While it was still funded, the EPA reported that small businesses and homes accounted for 12% of total US greenhouse gas emissions while personal vehicles accounted for less than 26% of total US emissions. Based on these numbers, we realized that even if every small business and home in America reduced its emissions to zero and each American drove cars that emitted no greenhouse gas, the United States wouldn’t even come close to that 80% goal.

We participated in traditional conservation efforts. We helped to save Bonanza Flats from the bulldozers and chainsaws. But, we have not yet saved Bonanza Flats from the droughts, the wildfires, the fungus-killing aspens, and the pine beetles all made worse by climate change.

We are ready for escalation. We are ready for direct action.

**

Beneath the positivity, the small victories, and the feel-good atmosphere characterizing life in a mountain town like Park City, a desperation quietly grows. Climate change worsens, mass extinction intensifies, and natural communities collapse. Parents and grandparents fear for the futures of their children and grandchildren. Older generations approach the end of their lives worrying that they failed the younger generations. Younger generations wonder if they truly are disempowered, or if disempowerment is an illusion ensured by the apathy they’ve been labelled with.

For the most part, the desperation remains unacknowledged, unnamed, and repressed. Removed from the violence producing our material comforts and granting us the ability to live in a place like Park City, many never feel the desperation. Those who do doubt the authenticity of their intuition and wonder if the desperation is a sign of mental illness, proof that something is wrong with them, or a character flaw. When the desperation is expressed, those who point it out are called alarmists, conspiracy theorists, and sensationalists. When the reality described is too obvious to ignore, those who describe it are accused of causing paralysis and depression.

Nevertheless, the planet’s health is critically threatened. And, things are getting worse. We must act urgently and decisively. For those of us who know this, the question becomes, “How do we encourage others to act with the necessary urgency and decisiveness?”

***

In 2012, the Summit Land Conservancy published the second edition of Park City Witness: A Collection of Essays and Artwork Celebrating Open Space. In her introduction, Cheryl Fox – Executive Director of the Summit Land Conservancy – wrote, “Today we face unprecedented challenges to our natural environment. Solving this problem is the moral challenge of our century. The question we must ask is not ‘what can I do?’ but ‘what is the right thing to do?’”

I completely agree with her. Several months before I read her words, I wrote in my essay “Park City is Still Damned,” “Don’t ask, ‘What can I do?’ Instead ask, ‘What needs to be done?’”

So, what is the right thing to do? What needs to be done? Ms. Fox concluded her introduction with, “I encourage you to read this book. Then go out to the trails, the mountains, the creek that you have helped to save. Watch for angels or demons and the messages they send, and then bear witness…”

It’s been five years since Summit Land Conservancy published its celebration of open space in Park City Witness. In that time, the list of the indicators of ecological collapse has only grown longer. Witnesses, testifying in court, take an oath to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. There are angels on the trails, the mountains, and in the creeks. But, there are demons, too. If we only bear witness to beauty, to optimism, and to celebration, we are liars. Telling the whole truth demands that we confront the demons, no matter how horrifying they are.

I have devoted my writing career to two principles: The land speaks. And, I have a responsibility to communicate what the land says as best I can. I hear the land speak of beauty. I also hear the land speak of horror. In Park City, while most writers and most artists focus on stories of beauty, who will confront the stories of horror?

We need new Park City witnesses. I cannot ask anyone to do what I myself am not willing to do. So, I commit, publicly, to being a new Park City witness. One who lives as honestly as possible with two realities. There is beauty and there is horror. The horror will consume the beauty if it is not confronted, described, and resisted.

To give my commitment substance, I have acquired a reliable vehicle, spent weeks researching, cleared my schedule, and formed a plan to visit places in Park City and across Utah where horror threatens to overwhelm beauty. These are places like the planned site for the Treasure Hill development, the Uintah Basin, oil refineries in North Salt Lake, the White Mesa uranium mill, and the coal mines in Price. My experiences will form a place-based series. Each essay will grow organically from the natural community it is written from. I welcome community discussion, comments, and feedback. The Deep Green Resistance News Service has graciously agreed to publish the writing this journey produces and you can follow along here. Please feel free to contact me.

My purpose is simple: In each place, I will search for beauty and I will search for horror. Then I will ask of that place, “What do you need?” I will listen for as long as I need to, knowing that the land rarely speaks in English and rarely observes a time recognizable by common human patience. After this, I will write. I will write as honestly as possible.

I hope to give a voice to those who feel the desperation. I hope to comfort those who feel crazy for the intensity of their concern. I hope to demonstrate that their concern is justified. I hope to catalyze the courage we so desperately need to resist effectively.

I hope to be a new Park City witness.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 8, 2017 | Alienation & Mental Health

One human language is much too small to convey the ever unfolding meanings at play in the world.

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

I am an environmental activist. I have depression. To be an activist with depression places me squarely in an irreconcilable dilemma: The destruction of the natural world creates stress which exacerbates depression. Cessation of the destruction of the natural world would alleviate the stress I feel and, therefore, alleviate the depression. However, acting to stop the destruction of the natural world exposes me to a great deal of stress which, again, exacerbates depression.

Either, the destruction persists, I am exposed to stress, and I remain depressed. Or, I join those resisting the destruction, I am exposed to stress, and I remain depressed.

Depressed if I do, depressed if I don’t. So, I fight back.

I will always struggle with depression. I know it sounds like the typically fatalistic expression of a depressed mind, but accepting this reality releases me from the false hope that I will ever live completely free from the guilt, hopelessness, and emptiness that are depression. Accepting this reality, frees the emotional energy I spent clinging to false hope. Instead of using this energy searching for a cure that never existed, I can devote this energy to activism and to managing depression in realistic ways.

Coming to this realization was not easy. It’s taken me five years since I was first diagnosed with a major depressive disorder, confirmation of the diagnosis from three different doctors in three different cities, two suicide attempts, and more emotional meltdowns than I can count to finally accept my predicament.

***

Uintah Basin drilling at night. Credit: Wikimedia

A recent drive through the oil fields in Utah’s Uintah Basin reminds me why depression will haunt me for the rest of my life.

The drive east on U.S. Highway 40 from Park City, UT to Vernal leaves me nowhere to hide. In my rearview mirror, melting snow sparkles as it dwindles high on the shoulders of the Wasatch Mountains. Climate change threatens Utah’s snowfall and Park City may be bereft of snow in my lifetime. Pulling my gaze from the mirror to look through my windshield, tall thin oil rigs rise from drilling platforms to pierce the sky after they’ve pierced the earth. Next to the platforms, well pumps move lethargically, doggedly up and down. The wells are mechanical vampires, stuck in slow motion, sucking blood from the earth.

While the rigs inject poison and the pumps extract oil, it’s hard not to think of the addict’s needles. Scars form on the basin floor where once-thick pinyon-juniper forests and rolling waves of sagebrush are piled in heaps around the fracking operations. The swathes of destruction betray addiction as surely as track marks.

I pass countless tanker trucks parked next to round, squat oil storage containers. The trucks are filling up with yellow crude before hauling the oil to refineries in Salt Lake. From there, the oil will be shipped all over the West to be burned. Each oil platform, each rig, each well I pass strikes a blow to my peace of mind. Each truckload of oil burned pushes the planet closer to runaway climate change and total collapse.

My intuition is infected with a familiar dread. Looking around me, I am met only with trauma. So, I look to the future. I see sea levels rising, cities drowning, and refugees fleeing. I see oceans acidifying, coral reefs bleaching, and aquatic life collapsing. I see forests burning, species disappearing, and topsoil blowing away.

I don’t see a livable future.

My hands tighten on the steering wheel, the muscles in my face cramp, and I feel nauseous. My left foot is restless. My right foot, though it is busy with the accelerator, is restless, too. I am speeding. My body is confused. It has no evolutionary reference for being trapped in the cab of a car while traveling at highway speeds.

If you could see through my flesh and bone to the organs forming my stress response system, what would you see? You’d see my adrenal glands pumping out stress hormones. You’d see the stress hormones preparing my body and brain to fight or flee. After a few minutes, you’d see my shrunken, damaged hippocampus trying to signal my adrenal glands that the threat has passed and to stop flooding my frontal cortex with stress hormones. You’d see my hippocampus fail, my adrenal glands continue to pump out hormones, and my risk for sinking into a full-blown episode of depression rise.

Oil well in Duchense County, Utah. Credit: Wikimedia

***

Neurobiological research suggests that the highly recurrent nature of depression is, in part, linked to the way stress hormones can produce brain damage. Advances in neuroscience unveil a conception of depression as a vicious cycle in the body’s stress response system. In a healthy system, adrenals produce hormones in response to stress. The stress passes and the hippocampus signals the adrenals to stop hormone production.

When the frontal cortex – especially the hippocampus and amygdala – is exposed to too many stress hormones, for too long, the frontal cortex begins to shrink. A damaged hippocampus fails to stop the adrenals which continue to produce stress hormones which continue to damage the hippocampus. Mood, memory, attention, and concentration are all affected. Problems with mood, memory, attention, and concentration create their own stresses which intensify the cycle.

Recent psychiatric findings paint a bleak picture. The American Psychiatric Association describes depression as “highly recurrent,” with at least 50% of those recovering from a first episode experiencing one or more additional episodes in their lifetime, and approximately 80% of those recovering from two episodes having another recurrence. Someone with three or more episodes has a 90% risk of recurrence. On average, a person with a history of depression will have five to nine separate depressive episodes in his or her lifetime.

I have had four distinct episodes of depression which all but guarantees that depression will continue to recur for me. I do experience periods of remission where I am relatively free of the symptoms of depression. But, even in these times, depression lurks in the shadows forcing me into a perpetual vigilance, struggling to avoid relapse. Depression may fade, but memories of depression’s pain never do. I live in fear, daily, that the next episode is just around the corner.

Mainstream psychology stops the discussion, here, to prescribe avoidance of places that trigger depression, like the Uintah Basin and to conclude that a combination of improving the hippocampus’ ability to switch off stress hormones, eliminating as much stress from the depressed’s life as possible, and coping with the stress that can’t be eliminated is the key to recovery.

I have no reason to believe this wouldn’t work, in another time or another world. But, most of the planet has been turned into places like the Uintah Basin. There are precious few places free from civilized violence. While our homes are on the brink of annihilation, while horror adheres to our daily experience, while protecting life requires facing these horrors, is the elimination of stress possible? Is coping honest?

***

Credit: Gordon Haber, National Park Service

Ecopsychology shows that the elimination of stress is not possible in this ecological moment. Where psychology is the study of the soul and ecology is the study of the natural relationships creating life, ecopsychology insists that the soul cannot be studied apart from these natural relationships and encourages us to contemplate the kinds of relationships the soul requires to be truly healthy. Viewing depression through the lens of ecopsychology, we can explain depression as the result of problems with our relationships with the natural world. Depression cannot be cured until these relationships are fixed.

This explanation begins with stress and the body’s relationship with it. Stress is fundamentally ecological and can be understood as flowing through an animal’s relationship with his or her habitat. The classic example of the ecological nature of an animal’s stress response system involves the relationship between prey and predator. When a moose is beset by wolves, her stress response system produces hormones that help her flee or fight the wolves.

The relationship formed between the wolf, the moose, the moose’s stress hormones, and the moose’s stress response system is one of the countless relationships necessary for the moose’s survival. This is true for everyone. Other relationships animals rely on include air, water, and space, animals of other species, members of the animal’s own species, fungi, flowers, and trees, the cells forming the animal’s own flesh, the bacteria in the animal’s gut, and the yeast on the animal’s skin. Relationships give an animal life, and in the end, relationships bring the animal’s death. In an animal’s death, other beings gain life. The history of Life is the history of these mutually beneficial relationships.

Civilized humans poison air and water, alter space, murder species, destroy fungi, flowers, and trees, infect cells, mutate bacteria, and turn yeast deadly. In short, they threaten the planet’s capacity to support Life. Not only do civilized humans destroy those we need relationships with, they destroy the possibility of these relationships in the future. Every indigenous language lost, every species pushed to extinction, every unique acre of forest clearcut is a relationship foreclosed now and forever.

Living honestly in this reality, we open ourselves to depression. Losing these relationships, and seeing a future devoid of the relationships we need, creates unspeakable stress. Living with this stress every day can flood the frontal cortex with stress hormones, shrink the hippocampus, and push the stress response system past its ability to recover.

If this happens, you may be haunted with depression for the rest of your life.

To experience major depressive disorder is to know consciousness is an involuntary bodily function. Just like your heartbeat, you cannot turn consciousness off without chemicals, a blow to the head, or some other violence to the body and brain. Awareness is a muscle, and perceiving phenomena is how this muscle works. Depression is constant pain accompanying perception. In the civilized world, pain and trauma reflect from countless phenomena. The destruction has become so complete, consciousness finds nowhere to rest in peace, no place free from the reminders of violence.

***

Credit: Lain McGilcrest / Regent College

I know I have described a harsh reality for those of us living with depression. It is, however, the reality. For many of us, depression is a lifelong illness. In the long run, accepting a harsh reality is always better than maintaining denial. I have found that accepting this reality helps me manage my depression daily and enables me to be a more effective activist.

Accepting that I will always struggle with depression does not imply giving up. On the contrary, accepting this struggle requires a commitment to daily discipline. Several of my doctors have compared depression to diabetes. Just like many diabetics have to monitor their blood sugar, avoid certain foods, and regular exercise, depressives must build a daily practice into their lives. For me, this means regular cardiovascular exercise that helps my body deal with stress hormones, getting eight hours of sleep nightly, drinking alcohol sparingly, limiting situations where I am tempted to ruminate, and a consistent investment in my social relationships both human and nonhuman.

Coming to grips with the lifelong nature of depression has also given me firepower against depression’s perpetual guilt. The guilt associated with depression can become so pervasive it builds layers on itself. I feel guilty, for example, when I am tired, when I can’t seem to focus on writing, when I cannot find the mental fortitude to see the tasks I’ve promised to complete through to conclusion. I remind myself that lack of energy and problems with concentration and goal-oriented thinking are symptoms of depression. Then, I feel guilty for forgetting and guilty for letting myself feel guilty.

Accepting that I will always struggle with depression is accepting that I will always struggle with the symptoms of depression like guilt, too. Knowing this, when I find myself mired in cycles of guilt, I stop trying to rationalize my way through the guilt and simply place the guilt in a corner where it doesn’t matter if I should feel guilty or not.

Accepting the lifelong nature of depression relieves me of the search for a cure. The personal search for a cure is quickly converted by depression into pressure to get better. This pressure becomes a sense of failure when depression’s symptoms intensify. While the world burns, the stress causing depression is always present. I may defend myself from this depression effectively for awhile but, the violence is so total and the trauma so obvious, there will be times that the stress overwhelms my defenses. This is not a personal failing and this is not my fault. I fight as hard as I can, but I will not always win.

Most importantly, acceptance makes me a better activist. I cannot separate my experience from the countless humans and nonhumans who make my experience possible. Fortunately, ecopsychology gives me a lexicon to communicate about the relationships creating my experience. Understanding that omnipresent stress, caused by the omnipresent destruction of the relationships that make us human, causes depression frees me from the voice telling me depression is my fault.

Before I could understand this, I had to open myself to the reality of these relationships. These relationships are our greatest vulnerability and our greatest strength. We cannot change this. The ongoing loss of these relationships is incredibly painful. If we want the pain to stop one day, we must fight back. That will be incredibly painful, too.

***

Credit: Pixabay

Life speaks, but rarely in English. One human language is much too small to convey the ever unfolding meanings at play in the world. Wind and water, soil and stone, fin, fur, and feather are only a few of Life’s dialects.

Tectonic plates tell mountains where to form. Blood in the water tells a shark food may be near. Foreign proteins on the surface of dangerous cells, tell your white blood cells to attack. A single chirp, formed in a prairie dog’s throat, lasting a mere tenth of a second, tells an entire colony the species and physical characteristics of an approacher.

You may not hear Life utter the words, “Stop the destruction.” But, Life’s languages are as diverse as the variety of physical experiences. The pain of depression is a physical experience, and it follows that Life speaks through depression. That pain will haunt me for the rest of my life. Life continues to speak. It says, “Fight back.”

Credit: Pixabay

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 11, 2017 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

A windmill blade knocks the head off a Cooper’s hawk interrupting the late afternoon peace in Spring Valley, just outside Ely, Nevada.

The blade tosses the hawk’s body onto yellow gravel the power company spread, over living soil, in circles around their windmills.

The ever-present Great Basin breeze, who usually whispers with a soothing tone through pinyon needles, juniper branches, and sage tops, becomes angry. Grazing cows pause their chewing and look up to consider the scene.

Heads of cheat grass poke through the gravel, only to droop with sorrow for the splayed feathers and twisted wings at their feet. Taller than cheat grass and crowding around the gravel’s edge, crested wheatgrass shakes and shutters with horror in the wind.

The collision’s suddenness and the sickening sound of the blade striking the hawk’s small skull breaks my awareness open with a pop. I seep across the valley floor. I mingle with the wounds on the land and recognize pain in places I previously overlooked. The windmills, the invasive plants, the cows, and the empty scars on the foothills marking pinyon-juniper clearcuts are all evidence of violence.

The gravel at my feet is the remains of stones and boulders that were exploded and crushed, loaded into trucks, and transported to Spring Valley as part of Pattern Energy’s Spring Valley Wind Farm project. Windmill construction means so much involves land clearances, building maintenance roads, and operation of fossil-fuel intensive heavy machinery.

Before the gravel was dumped and the construction project started, the ground I stand on was covered in a complex mosaic of lichens, mosses, microfungi, green algae, and cyanobacteria that biologists call a “biological soil crust.”

Across the Great Basin, biological soil crusts are integral to protecting soil surfaces from erosion. They are also vulnerable to disturbance by construction projects like the one that brought the windmills here. The lichen components of these disturbed crusts can take 245 years to recover. Far worse, soil losses due to erosion following mechanical disturbances can take 5,000 to 10,000 years to naturally reform in arid regions.

The windmills that tower above me fill the air with a buzzing, mechanical sound. Built only four miles from a colony of millions of Mexican free-tailed bats at the Rose Guano Cave, the windmills killed 533 bats in 2013, triple the amount allowed by federal regulations. The majority of these bats are killed by barotrauma. Rapid or excessive air pressure change, produced by windmills, causes internal hemorrhaging. In less abstract language, the bats’ lungs explode.

Both cheatgrass and crested wheatgrass are invasive species. Global shipping routes, which have long been tools of colonialism, brought cheatgrass to North America through contaminated grain seed, straw packing material, and soil used as ballast in ships. Cheatgrass outcompetes native grasses for water and nutrients. It drops seeds in early summer before native grasses and then drys out to become highly flammable.

When wildfires rip through areas cheatgrass has invaded, native grasses are destroyed without seeding. In the fall, after native grasses have burned, cheatgrass seeds germinate and cheatgrass dominance expands. This dominance has been disastrous for the Great Basin. Fire return intervals have gone from between 60-110 years in sagebrush-dominated systems to less than 5 years under cheatgrass dominance.

While cheatgrass was imported by accident, crested wheatgrass was imported from Asia in 1898. By the 1890s, Great Basin rangelands were depleted of water, soil, and economically useful vegetation. Ranchers needed cheap feed for their livestock and crested wheatgrass provided it. It outcompetes native grasses, grows in tight bunches that choke out other species, quickly forms a monoculture, and reduces the variety of plant and wildlife species in places it takes hold. Worst of all, crested wheatgrass supports a destructive ranching industry that should have collapsed decades ago.

Ranching is one of the most ecologically destructive activities in the Great Basin. Livestock grazing depletes water supplies, causes soil erosion, and eliminates the countless trillions of small plants forming the base of the complex food web supporting all life in the region. Ranchers have nearly killed off all the top carnivores on western rangelands and jealously guard their animals against the re-introduction of “unacceptable species” like grizzly bears and wolves.

Ranchers, always searching for new rangeland, encourage government agencies like the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the US Forest Service (USFS) to clear-cut forests and remove sagebrush to encourage the growth of graze for their livestock. In the hills north of the wind farm, pinyon pines and junipers lie in mangled piles where they were “chained.”

Chaining is the preferred method for destroying forests here. To chain a forest is to stretch a US Navy battleship anchor chain between two crawler tractors which are then driven parallel to each other while ripping up every living thing in their path.

Ship chain used to clear forests. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Nevada Highway 893 runs to my left along the west side of the valley. If I followed the road north a few miles, I would run into one of the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s (SNWA) test wells. SNWA installed these wells in the preparation of its Clark, Lincoln, and White Pine Counties Groundwater Development Project that would drain Spring Valley of water and, then, transport the water by pipeline to support Las Vegas’ growing population.

Fortunately, the project has been successfully stalled in court by determined grassroots activists. But, if SNWA eventually prevails, Spring Valley will quickly dry up and little life, endemic or invasive, will survive here.

***

The reminders of violence I encounter in Spring Valley reflect global problems. Windmills are a symptom of the dominant culture’s addiction to energy. The roads here will carry you to highways, highways to interstates, and interstates to airports.

There is virtually nowhere left on Earth that is inaccessible to humans with the privilege, power, and desire to go wherever they will. To gain this accessibility, these humans are so thoroughly poisoning the atmosphere with greenhouse gas emissions global temperatures are rising.

Invasive species – cows, cheat grass, crested wheatgrass, European settlers – are colonizers. They each colonize in their own way. The cows replace elk, pronghorn, wolves, and bears. The grasses eliminate natives by hoarding nutrients and water. They reproduce unsustainably and establish monocultures. When that doesn’t work, they burn the natives out. And, the settlers do the same.

The violence of civilized life becomes too obvious to ignore and the land’s pain threatens to overwhelm me. Despair accompanies these moments. When all I see is violence, it is easy to conclude that violence is all there is, all there ever was, and all there ever will be. Claims I’ve heard repeated countless times echo through my mind.

Humans are selfish. This is just what we do. We will kill ourselves, but the planet will recover…eventually. Humans have been butchering each other for centuries and we’ll butcher each other for centuries more if we don’t destroy the world first.

I stand paralyzed under a windmill, with a decapitated hawk at my feet, struggling through my thoughts for who knows how long, when the blue feathers of a pinyon jay catch my eye. At first, it’s the simple beauty of her color that attracts my attention. But, it’s the strangeness of the phenomenon that keeps my attention.

Rows of windmills form the wind farm. I stand under the northernmost row and about one hundred yards separate the rows. The jay lands on a barbed wire fence post about halfway between the row I’m standing under and the first row south of me. Her presence is strange for two reasons. First, pinyon jays prefer to live in pinyon-juniper forests and there are no trees for a mile in either direction. Second, pinyon jays are very intelligent, and she must have known that to brave the circling windmill blades is to brave the same death the Cooper’s hawk just experienced or the barotrauma so many bats experience.

The despair I felt a few moments ago is fading. As I approach the jay I see her picking through a pinyon pine cone. She picks deftly at it before she pulls a pine nut from the brown folds of the cone. It’s not until she lifts her head, with the pine nut in her beak, that I understand.

She flew down from the forests, through dangerous windmill blades, to show me a pine nut.

Pinion Jay – Photo: Wikimedia Commons

***

Pine nuts represent the friendship humans and pinyon-juniper forests have shared for thousands of years. Pinyon charcoal and seed coats have been found in the 6,000-year-old Gatecliff Shelter in central Nevada. Pinyon seed coats have been found with 3,000-year-old artifacts in Hogup Cave in northwestern Utah. Many of the Fremont culture’s ruins (circa 1000 AD) in eastern Utah also show pinyon use.

Pine nuts are symbols of true sustainability. I’ve heard many traditional, indigenous people explain that sustainability requires making decisions with the succeeding seven generations in mind. When the health of the seventh future generation guides your relationship with the land, overpopulation, drawdown, pollution, and most forms of extraction become unthinkable. European settlers arrived to find indigenous peoples in the Great Basin, like so many indigenous peoples around the world, living in cultures that existed for centuries in balance with the land.

And, the pine nut made these cultures possible.

The Washoe, Paiute, and Shoshone all developed cultures centered on pine nuts. Pinyon pine expert, Ronald Lanner notes, “Just as life on the plains was fitted to the habits of the buffalo, life in the Great Basin was fitted to the homely, thin-shelled nut of the singleleaf pinyon.” Pinyons give their nuts freely and harvesting them involves no damage to the trees. In fact, pine nuts are seeds. Animals who collect and gather the seeds – like pinyon jays, rats, mice, and humans – help the trees reproduce.

It’s a beautiful relationship: pinyon pines offer animals food, and animals offer pinyon pines regeneration. At a time when the survival of life on Earth depends upon humans embracing their role as animals, the relationship the Washoe, Paiute, and Shoshone built with pinyon pines serves as a model for the world.

Relying on the research of American Museum of Natural History archaeologist David Hurst Thomas, Lanner describes the central role the annual pinyon festival played in Western Shoshone life. He writes, “…when pinyon harvest time arrived, Shoshone bands would come together at a prearranged site. There they would harvest nuts, conduct communal rabbit drives, and hold an annual festival. The pinyon festival was the social highlight of the year and was often attended by several hundred people. At night…there was dancing…There was gambling among men and courting among the young. Marriages were arranged and sexual liaisons conducted.”

Pine nut crops, like all natural processes, are subject to variation. There are good yields and bad yields. Human cultures dependent on the land are constantly confronted with a choice. Either humans can tighten their belts and reduce their populations voluntarily. Or, they can exploit the land, stealing resources from the future to meet the needs of the present.

Lanner describes how Western Shoshone sustainability was maintained, “…the pinyon festival was used as an opportunity for regulating the future size and distribution of Shoshone populations. If at the festival the intelligence from all areas foretold a failure of next year’s crop, then measures could be taken to avoid mass starvation…Births could be limited by sexual abstinence or abortion. One or more twins could be killed at birth, as could illegitimate children…The sick and the old could be abandoned. A widow might be killed and buried beside her husband.”

Some of these measures may seem harsh to us today. But, when we consider the violence necessary to sustain today’s civilized, human populations, we will realize that some of these difficult decisions are what true sustainability looks like. Killing a twin or abandoning the sick is small violence compared to the mass violence of deforestation, anthropogenic desertification, and climate change.

***

The pinyon jay in Spring Valley shows me both a pine nut and the history of human sustainability. Even though Spring Valley, with the rest of the world, currently reflects too much human violence, the vast majority of human history reflects true sustainability. Modern humans have existed for 200,000 years. For the vast majority of that time, most of us lived in cultures similar to the Western Shoshone. We must not forget where we come from.

Meanwhile, ecological collapse intensifies. Violence against the natural world is so pervasive it must be considered a war. Perceiving this war hurts. The pain offers us two choices: endurance or cure. Either the pain is inevitable, an unavoidable fact of life that must be endured. Or, the cause of the pain can be treated and healed.

The pervasiveness of violence tempts us to conclude that it is inevitable. When everywhere we look, we are met with human destruction, it is easy to believe that humans are inherently destructive. This is one reason why the dominant culture destroys the natural world so zealously. If violence is inevitable, there is no reason to stop it.

This is also why the dominant culture works to destroy those non-humans we’ve formed ancient friendships with. If the dominant culture eradicates bison, it destroys our memory of how to live sustainably on the Great Plains. If the dominant culture eradicates salmon, it destroys our memory of how to live sustainably in the Pacific Northwest. If the dominant culture eradicates pinyon-juniper forests, it destroys our memory of how to live sustainably in the Great Basin.

There is a war being waged on the natural world and wars are fought with weapons. The pinyon jay brings me a weapon against the despair I feel recognizing pervasive violence in Spring Valley. She shows me that the violence is not inevitable. She shows me the path to true sustainability, and in doing so, shows me the path to peace.

To learn more about the effort to protect pinyon-juniper forests, go to Pinyon Juniper Alliance. You can contact the Alliance here.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 21, 2017 | Strategy & Analysis

by Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

In my essay, Park City is Damned: A Case Study in Civilization, I described the vicious cycle Park City, Utah is caught in and explained how the city cannot exist for much longer.

There are far more humans in Park City than the land can support, so the necessities of life must be imported. Importing these necessities costs money and requires an industrial infrastructure. Park City makes its money through a tourist industry that relies on snow, but climate change, produced by the same industrial infrastructure bringing the necessities of life, is destroying the snow. The industrial infrastructure must be dismantled to stop climate change so the snow may survive. Either the snow or the industrial infrastructure will fail.

And, Park City will, too.

Not long after the essay was published, I attended a gathering for an emerging group PCAN! or Park City Action Network. The gathering’s goals included to “create a network for young professionals and build community, to learn what’s going on in local politics, and to find other like-minded individuals to create a strong collective voice.”

I think I’m still young (turned 30 in March), I have a law degree and license (in Wisconsin), and I’m interested in finding like-minded individuals to create a strong collective voice, so I went.

A man approached me, and said. “You’re Will Falk, right? You wrote that article?”

I was embarrassed and nervous people were going to hate me for what I wrote. But, his eyes and body language were sincere, so I told the truth. He asked, “So, you think Park City won’t last?

“Can’t physically last,” I clarified.

“ Right. And, solar power isn’t the answer? Wind power, either?”

“No,” I responded. He looked at me earnestly for a few seconds, looked around at the room of concerned, young professionals, and said, more to himself than to me, “Park City is still damned huh?”

“Still damned,” I said. He sighed and asked,“What the hell have we been working on all this time?”

I shrugged. I wasn’t sure what to say, but I could see acceptance in his face. I simply tried to meet his gaze. Finally, he asked, “What can I do?”

***

Park City’s vicious cycle is a reflection of the vicious cycle the global human population is caught in. There are far more humans than the planet can support sustainably, so the necessities of life must be stolen from non-humans and the future. This theft is managed through an industrial infrastructure powered by fossil fuels and the operation of this infrastructure is destroying the planet’s total life-supporting capacity. It is pushing the climate to temperatures too warm for most species, pushing oceanic life perilously close to total collapse, and contaminating, with toxins and carcinogens, the bodies of every civilized individual.

Unfortunately, with more than half the global human population now living in cities, most humans depend on this system for food, for clean water, and for shelter. Humans have backed themselves into a corner. If this system collapses, huge, urban populations of humans will be left without the necessities of life. But the system must collapse for the planet to survive. Ignorance of physical reality cannot save us from it; either the planet or the industrial infrastructure will fail.

Basic ecology gives us another way to understand this. In ecologic terms, humans have overshot the planet’s carrying capacity through dependence on a drawdown method of temporarily extending carrying capacity. Crash is inevitable, and the longer drawdown occurs, the smaller Earth’s total carrying capacity will be after the crash.

Humans are animals and, as animals, require habitat. Every habitat has a total life-supporting capacity, or carrying capacity. Carrying capacity is the maximum population of a given species which can be supported by a particular habitat indefinitely. Earth, even as the largest habitat, is finite with a specific carrying capacity.

In his ecological classic Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change, Dr. William R. Catton Jr. explains that civilized humans “have several times succeeded in taking over additional portions of the earth’s total life-supporting capacity, at the expense of other creatures.”

Catton’s phrase “at the expense of other creatures” is a nice way of describing extermination. Using 1970 population totals and current trends, the World Wildlife Fund recently published a prediction that by 2020 two-thirds of the Earth’s total vertebrate population (mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles) will have been killed by human activities. Biologist Paul Ehrlich, who studies population at Stanford University, says that half of all individual life forms humans are now aware of have already disappeared.

Civilized humans have learned to rely on technologies that augment human carrying capacity in temporary ways. These augmentations are necessarily temporary because the finiteness of every habitat places physical limits on population growth. In other words, you can’t steal more than everything.

The latest and deadliest of the technologies humans have used to augment carrying capacity revolve around the exploitation of the “planet’s energy savings deposits, fossil fuels.” Through these exploitative technologies powered by fossil fuels, Catton argues, civilized humans are now engaged in a “drawdown method of extending carrying capacity.” This method is “an inherently temporary expedient by which life opportunities for a species are temporarily increased by extracting from the environment for use by that species some significant fraction of an accumulate resource that is not being replaced as it is drawn down.”

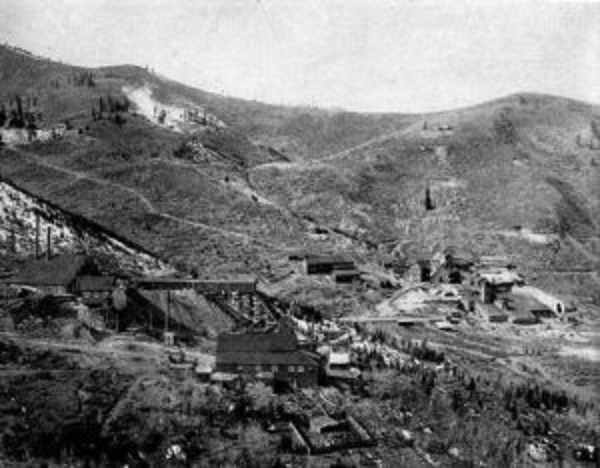

Daly West and Quincy Mines in Park City (circa 1911) / Wikimedia

This drawdown has allowed humans to overshoot the planet’s carrying capacity. Overshoot leads to a situation where a portion, or even all, of a population cannot be supported when temporarily available, and finite, resources are exhausted. When these resources run out, crash inevitably follows.Civilized humans are destroying countless so-called “resources” that are not being replaced as they are murdered. The extraction of fossil fuels is an easy example. But, civilized humans are also cutting forests and plowing grasslands faster than they can grow back, they’re stripping topsoil faster than it rebuilds, and they’re heating the planet more intensely than life can evolve to keep pace.

Richard Heinberg, Senior Fellow at the Post Carbon Institute, describes what is happening as the ecological phenomenon known as “population bloom” in his book The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality. When a species finds an abundant, easily acceptable energy source (in our case, fossil fuels), its numbers increase while taking advantage of the surplus energy. Speaking to the inevitability of crash, Heinberg writes, “In nature, growth always slams up against non-negotiable constraints sooner or later…Population blooms (or periods of rapid growth) are always followed by crashes and die-offs. Always.”

Crash following overshoot is bad enough, but the problem doesn’t end there. If a population exists in overshoot for too long, drawing down too many of its habitat’s necessities of life, the habitat’s carrying capacity can be permanently reduced. To use simple numbers, start with a carrying capacity of 1000 humans. What happens if 1200 humans, then 1500 humans, then 2000 humans live on the land for too long? Or those original 1000 humans steal other creatures’ carrying capacity and convert it to human use?

That land base’s carrying capacity can be permanently reduced to 800 humans, 400, and so on, over time, all the way to zero. Eventually, the population will crash and that land base will never be capable of supporting humans, or any other life, again. This is as true for the carrying capacity of a small locale like Park City as it is for the carrying capacity of the whole planet.

The horror we live with comes into focus. Most human lives are made possible by a system that will collapse, and the longer that system operates, literally eating Earth’s total carrying capacity, the less chance other lives – human and non-human – have to continue existing.

We have two choices. We can live in denial, even as the evidence of the planet’s murder piles around us. We can anesthetize ourselves with the comforts produced by this insane arrangement of power. We can pray for our own death before the worst of the collapse happens. In short, we can do nothing.

Or, accepting responsibility as people who love each other, love our non-human kin, and love life, we can stop the industrial system from destroying our beloveds.

Once you’ve decided to stand on the side of life, the question becomes, How? How do ensure as much life as possible will survive the coming crash? How do we stop industrial civilization from permanently reducing the planet’s carrying capacity to nil?

***

Longtime environmental activists and writers Derrick Jensen, Lierre Keith, and Aric McBay created a concrete strategy for an effective resistance movement in their book Deep Green Resistance. They named that strategy “Decisive Ecological Warfare (DEW).”

Before you object to the term “warfare,” consider this: In the past, wars killed humans. Today, with human activities killing 200 species daily, we are engaged in a war where whole species are exterminated. We readily recognize the chemical warfare characterizing so many conflicts of the last century and, today, industrial processes create a reality where every mother on the planet now has dioxin, a known carcinogen,in her breast milk.

This is a war. And, we are losing. Badly. If we’re going to win this war, we need to act like a serious resistance movement.

DEW gives us a comprehensive strategy. It is centered on two primary goals. Goal 1 is “to disrupt and dismantle industrial civilization; to thereby remove the ability of the powerful to exploit the marginalized and destroy the planet.” Goal 2 is “to defend and rebuild just, sustainable, and autonomous human communities, and, as part of that, to assist in the recovery of the land.”

Disrupting and dismantling industrial civilization is primary. If industrial civilization is not stopped, then the second goal will be impossible. The land will be pushed past its ability to recover and there will be too few necessities of life left to support autonomous human communities.

Accomplishing these goals will involve five smaller strategies. First, resisters will “engage in direct militant actions against industrial infrastructure.” This may frighten some people and others may feel physically incapable of actions like these. If you can’t engage in these kinds of actions, the people who can will need your material support. In a place like Park City, steeped in privilege, the most obvious form of support the community could offer is money. Those in power are incredibly well-funded. We’ll never match them dollar for dollar. But, that doesn’t mean money can’t be put to good use.

Second, they will “aid and participate in ongoing social and ecological justice struggles; promote equality and undermine exploitation by those in power.” My friend Rachel Ivey, a brilliant feminist writer and organizer, often connects social and ecological justice with the truth that, “Oppression is always tied to resource extraction.” This means that industrial civilization has been built on the backs of people of color, indigenous peoples, the poor, and women. These groups are often on the movement’s front lines, fighting for survival. We must join them in true solidarity.

Third, they will “defend the land and prevent expansion of industrial logging, mining, construction, and so on, such that more intact land and species will remain when civilization does collapse.” Pipeline and port blockades, tree sits, and other forms of non-violent direct action aimed at physically preventing those in power from destroying more of the land is an essential piece of the puzzle. There are roles in the resistance for pacifists and others personally and philosophically unwilling to engage in more militant actions.

Fourth, they will “build and mobilize resistance organizations that will support the above activities, including decentralized training, recruitment, logistical support, and so on.” A serious resistance movement needs artists, writers, and those skilled in marketing and mass media communications. It also needs quartermasters, organizational psychologists, and others trained in logistical thinking.

Finally, resisters will “rebuild a sustainable subsistence base for human societies (including perennial polycultures for food) and localized, democratic communities that uphold human rights.” As collapse intensifies, we are going to need permaculturists, gardeners, and urban farmers to produce food when the industrial networks, currently transporting food, fail.

All kinds of skills will be necessary to stop industrial civilization, but the most important thing is that industrial civilization is actually stopped. All of our efforts must support this primary goal. Right now, the dominant system is barreling down a path that ends in total ecological collapse. Not only is the human species endangered with extinction, but every species – save, maybe a few microscopic species of bacteria – is threatened with annihilation. Before anything else, we must knock the dominant system off that path.

***

I return to answering the question, “What can I do?”

This is the wrong question. Don’t ask, “What can I do?” Instead ask, “What needs to be done?”

Go outside. Look around. Take a deep breath. Feel the oxygen, exhaled by trees, seep into your lungs. Let your breath go, and listen as the trees inhale the carbon dioxide your breath releases. Ask those trees what they need.

Climb to the top of the nearest hill. Find a boulder to sit on and wait. Match the land’s patience. Let gravity pull your bones closer to their ancestors, the bones of the earth. Watch the ants march, dutifully performing work for their community. Listen to the geese arriving for the spring, celebrating their return. Ask the stones, the ants, and the geese what they need. Ask them what needs to be done.

They’ll tell you they need to live.

The trees will tell you that warming temperatures cause cavitation, or bubbles, in the water flowing from their roots to their topmost leaves and that these bubbles kill them as surely as artery blockages kill humans.

The stones will tell you how quickly everything has changed. They will tell you how species they used to watch disappeared faster than stones, who exist on geologic time, can contemplate. They will tell you about mountain top removal, open-pit mining, and earthquakes caused by fracking.

The ants will tell you how they’ve long been involved in planetary cooling processes. They’ll show you how they’re working as hard as they can to build limestone by freeing calcium carbonate from minerals in the soil. And, in the process, trapping as much carbon dioxide as they can.

The geese will tell you of frantic searches for disappearing wetlands, of once wild rivers dammed, drying, and no longer flowing to the sea.

When you stop asking “what can I do?” to begin asking “what needs to be done?” it is true, you may expose yourself to a world in pain. But, you’ll also find countless allies asking the same questions you are. You may rip the scar tissue of denial that has been shielding your eyes from the near-blinding truth. But, once you let the sunlight in, once you step outside into the real world, you’ll open yourself to a world fighting like hell to survive.

We’ve been waiting for you.

Will Falk moved to the West Coast from Milwaukee, WI where he was a public defender. His first passion is poetry and his work is an effort to record the way the land is speaking. He feels the largest and most pressing issue confronting us today is the destruction of natural communities. He received a Society of Professional Journalists, San Diego Chapter, 2016 Journalism award. He is currently living in Utah.

To repost this or other DGR original writings, please contact newsservice@deepgreenresistance.org