by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 9, 2018 | Culture of Resistance

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Culture of Resistance” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance

The final difference between the alternative culture and a culture of resistance is the issue of spirituality. Remember that the Romantic Movement, arising as it did in opposition to industrialization, upheld Nature as an ideal and mourned a lost “state of nature” for humans. Emotions were privileged as unmediated and authentic. Nonindustrialized peoples were cast as living in that pure state of nature. The Wandervogel idealized medieval peasants, developing a penchant for tunics, folk music, and castles. Writes Keith Melville,

Predictably, this attraction to the peasantry never developed into a firm alliance. For all their vague notions of solidarity with the folk, the German youths did not remain for long among the peasants, nor did they take up political issues on their behalf. What the peasants provided was both an example and a symbol which sharpened the German Youth Movement’s dissent against the mainstream society, against modernity, the industrialized city, and “progress.”86

When the subculture was transplanted to the US, there were no peasants on which the new Nature Boys could model themselves. Peasant blouses and folkwear patterns found a role, but the real exploitation was saved for Native Americans and African Americans. Primitivism, an offshoot of Romanticism, constructs an image of indigenous people as timeless and ahistoric. As I discussed in the beginning of the chapter, this stance denies the indigenous their humanity by ignoring that they, too, make culture. Primitivism sees the indigenous as childlike, sexually unfettered, and at one with the natural world. The indigenous could be either naturally peaceful or uninhibited in their violence, depending on the proclivities of the white viewer. Hence, Jack Kerouac could write:

At lilac evening I walked with every muscle aching among the lights of 27th and Welton in the Denver colored section, wishing I were a Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough music, not enough night.87

He’d rather be black? Really? Would he rather have a better chance of going to jail than going to college? Would he rather have only one thirty-eighth the wealth of whites? Would he really want to face fire hoses and lynching for daring to struggle for the right to vote? This is Romanticism at its most offensive, a complete erasure of the painful realities that an oppressed community must endure in favor of the projections of the entitled. And depressingly, it’s all too common across the alternative culture.

The appropriation of Native American religious practices has become so widespread that in 1993 elders issued a statement, “The Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality.” The Declaration was unanimously passed by 500 representatives from forty Lakota tribes and bands. The statement could not be clearer: white people helping themselves to Native American religious practices is destructive enough to be called genocide by the Lakotas. The elders have spoken loud and clear and, indeed, even reaffirmed their statement. We should have learned this in kindergarten: don’t take what’s not yours. Other people’s cultures are not a shopping mall from which the privileged get to pick and choose.

Americans are living on stolen land. The land belongs to people who are still, right now, trying to survive an ongoing genocide. Those people are not relics of some far distant, mythic natural state before history. They live here, and they are very much under assault. Native Americans have the highest alcoholism rate, highest suicide rate, poorest housing, and lowest life expectancy in the United States. From every direction, they’re being pulled apart.

Let’s learn from the mistakes of the Wandervogel. Their interest in peasants had nothing to do with the actual conditions of peasants, nor with the solidarity and loyalty that the rural poor could have used; it had everything to do with their own privileged desires. Judging from my many years of experience with the current alternative culture, nothing has changed. The people who adopt the sacred symbols or religious forms of Native Americans—the pipe ceremony, inipi—do it to fulfill their own perceived needs, even over the Native Americans’ clear protests. These Euro-Americans may sometimes go a step further and try to claim their actions are somehow antiracist, a stunning reversal of reality. It doesn’t matter how much people feel drawn to their own version of Native American spirituality or how much a sweat lodge (in all probability led by a plastic shaman) means to them. No perceived need outweighs the wishes of the culture’s owners. They have said no. Respect starts in hearing no—in fact, it cannot exist without it. Just because something moves you deeply, or even speaks to a painful absence in your life, does not give you permission. As with the Wandervogel, the current alternative culture’s approach is never a call for solidarity and political work with Native Americans. Instead, it’s always about what white people want and feel they have a right to take. They want to have a sweat lodge “experience.” They don’t want to do the hard, often boring, work of reparation and justice. If, in doing that work, the elders invite you to participate in their religion, that’s their call.

Many people have longings for a spiritual practice and a spiritual community. There aren’t any obvious, honorable answers for Euro-Americans. The majority of radicals are repulsed by the authoritarian, militaristic misogyny of the Abrahmic religions. The leftist edges of those religions are where the radicals often congregate, and that’s one option; you don’t have to check your brain at the door, and you usually get a functioning community. But for many of us, the framework is still too alienating, and feels frankly unreformable. These religions have had centuries to prove what kind of culture they can create, and the results don’t inspire confidence.

Next up are the pagans and the Goddess people. Unlike the Abrahmists, they often offer a vision of the cosmos that’s a better fit for radicals. Some of them believe in a pantheon of supernaturals, and show an almost alarming degree of interest in the minutia of the believers’ lives. Other pagans believe in an animist life force: everything is alive, sentient, and sacred. But if the theology is a better fit, the practice is where these religions often fall apart. They may be based on ancient images, but the spiritual practices of paganism are new, created by urban people in a modern context. The rituals often feel awkward, and even embarrassing. We shouldn’t give up on the project; ultimately, we need a new cosmic story and religious practices that will keep people linked to it. But new practices don’t have the depth of tradition or the functioning communities that develop over time.

In order to understand where the pagans have gone astray, it may be helpful to discuss the function of a spiritual tradition. Three elements that seem central are a connection to the divine, communal bonding, and reinforcement of the culture’s ethic. What forms of the sacred are sought by the subculture, and by what paths does it intend to reach them? Obviously a community broad enough to encompass everything from crystal healing to “Celtic Wicca” will have a multitude of specific answers. But taken as a whole, the spiritual impulse has been rerouted to the realm of the psychological—the exact opposite of a religious experience.

By whatever name you wish to call it, the sacred is a realm beyond human description, what William James rightly describes as “ineffable.” The religious experience is one of “overcoming all the usual barriers between the individual and the Absolute … In mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness.”88 He describes this experience as one of “enlargement, union, and emancipation.”89 James offers a startlingly accurate description of that ineffable experience. But spiritual enlargement, union, and emancipation do not emerge from a focus on our psychology. We experience them when we leave the prisons of our personal pains and joys by connecting to that mystery that animates everything. The arrow—the spiritual journey—leads out, not in. But like everything else that might lend our lives strength and meaning, spiritual life—and the communities it both needs and creates—has been destroyed by the dictates of capitalism. The single-pointed focus on ourselves as some kind of project is not just predictably narcissistic, but at odds with every religion worth the name. The whole point of a spiritual practice is to experience something beyond our own needs, pains, and desires.

Ten years ago, I attended a weekend workshop called “The Great Goddess Returns.” I was already leery of these events back then, but there was one scholar I wanted to hear. The description, in so many words, offered what many people long to find: support, community, empowerment, relief from pain and isolation, and connection to ourselves, each other, the cosmos. These are valid longings and I don’t mean to dismiss anyone’s struggle with loneliness, alienation, or trauma. My criticism is directed instead at the standard form of the faux solutions into which neopaganism has fallen.

Drumming from a CD thumped softly through the darkened room. A hundred people were told to shut their eyes and imagine a journey back through time to an ancient foremother in a cave. I wasn’t actually sure what the point was, but I didn’t want to cultivate a spiritual Attitude Problem so early in the day, so I visualized. We were then handed a small piece of clay. No talking was allowed to break the sacrosanct if technological drumming. We were told to make something with the clay. Okay. It being March, and I being a gardener, I formed a peapod. Time ticked on. The drumming was more baffling than meaningful. And how long could it take people to mold a brownie size bit of clay? I kept waiting, the drumming kept drumming. Finally we were told to crumble up what we had made. All right. I smooshed up my peapod, and went back to waiting and my internal struggle against the demons of attitude. Boredom is annoying. It’s also really boring. I didn’t want to look around—everyone was hunched over with a gravitas that left me bewildered—but I was starting to feel confused on top of bored. Had I missed the part where they said, “Destroy your sculpture one mote at a time”? Finally, the rapture descended: further instructions. “Make your sculpture again,” came the hushed voice. What? Why? I hadn’t particularly wanted the first peapod. Did I have to make another one? Meanwhile, the drums banged on and on, emphasizing my growing ennui, and again, heads all around me bent to the work of clay like it was Day Six in the Garden. I reformed my peapod, which took about sixty seconds, then waited another eternity. I was ready to have a Serious Talk with whoever invented the drum.

Then the lights were slowly raised, a dawn to this long night of the bored soul. We were quietly divided into groups of ten and given the following instructions: “Talk about what you just experienced.”

Talk about … what? I made a pea pod. I crushed a pea pod. I remade a pea pod. For dramatic tension, I tried not to get bored.

Luckily, I was the seventh person in the circle, which gave me time to recognize the pattern and understand the rules. Because everyone else already understood. Being dwellers in the Land of Psychological Ritual, they knew too well what was expected. First up was a woman in her fifties. I don’t remember what she made with her clay. I do remember what she said. Crumbling up her sculpture brought her back to the worst loss of life, the death of her infant daughter. She cried over her clay, and she cried again while telling us, a group of complete strangers.

The next one up said it was her divorce, that crumbling the clay was the end of marriage. She cried, too.

For the third, the destruction of her clay was the destruction of her child-self when her brother raped her when she was five. She trembled, but didn’t cry.

The fourth woman’s clay was her struggle with cancer.

I had to stop paying attention right about then because I had to figure out what I was going to say.90 But I was also reaching overload. Not because of the pain in these stories—after years as an activist against male violence, I have the emotional skills to handle secondary trauma—but because the pain in their stories deserved respect that this workshop culture actively destroyed. This was a performance of pain, a cheapening of grief and loss that I found repulsive. How authentic to their experiences could these women have been when their response was almost Pavlovian, with tears instead of saliva? Smoosh clay, feel grief. Not knowing the expectation—not having trained myself to produce emotion on demand—I felt very little, beyond annoyance, during the exercise, and a mixture of unease, pity, and repugnance during the “sharing circle.” I had no business hearing such stories. We were strangers. I did not ask for their vulnerability nor did I deserve it. To be told the worst griefs of their lives was a violation both of the dignity such pain deserves and of the natural bonds of human community. This was not a factual disclosure—“I lost my first child when she was an infant”—but a full monty of grief. And it was wrong.

A true intimacy with ourselves and with others will die beneath that exposure. Intimacy requires a slow, cumulative build of safety between people who agree to a relationship, an ongoing connection of care and concern. The performance of pain is essentially a form of bonding over trauma, and people can get addicted to their endorphins. But whatever else it is, it’s not a spiritual practice. It’s not even good psychotherapy, divorced as it is from reflection and guidance. If you’re going to explore the shaping of your past and its impact on the present, that’s what friends are for, and probably what licensed professionals are for.

This “ritual” was, once more, a product of the adolescent brain and the alterna-culture of the ’60s, which imprinted itself unbroken across the self-help workshop culture it stimulated. No amount of background drumming will turn self-obsession and emotional intensity into an experience of what Rudolph Otto named “the numinous.” It will not build a functioning community. “Instant community” is a contradictory as “fast food,” and about as nourishing.

I have done grocery shopping after someone’s surgery, picked up a 2:00 am call to help keep a friend’s first, bottomless drink at bay, and taken friends into my home to die. I’ve also celebrated everything from weddings to Harry Potter releases. True community requires time, respect, and participation; it means, most simply, caring for the people to whom we are committed. A performative ethic is ultimately about self-narration and narcissism, which are the opposite of a communal ethic, and its scripted intensity is an emotional sugar rush. Why would anyone try to make this a religious practice?

I have way too many examples of this ethos to leave me with much hope. Some of the worst instances still make me cringe (white people got invited to an inipi and all I got was this lousy embarrassment?). I’ve been included in indigenous rituals and watched the white neopagans and other alterna-culturites behave abominably. Pretend you got invited to a Catholic Mass: would you start rolling on the floor screaming for your mother as the Catholics approached the rail for communion? And would you later defend this behavior as a self-evidently necessary “catharsis,” “discharge,” or “release of power”? When did pop psychology get elevated to a universal component of religious practice? Meanwhile, do I even need to say, the traditional people would never behave that way either at their own or anyone else’s sacred ceremonies. And they’d rather die than do it naked. Their dignity, the long stretches of quiet, the humility before the mystery, all build toward an active receptivity to the spiritual realm and whatever dwells there. The performative endorphin rush is a grasping at empty intensity that will never lead out of the self and into the all. Nor will it strengthen interpersonal bonds or reinforce the community’s ethics, unless those ethics are a self-indulgent and increasingly pornified hedonism, in which case it’s doomed to failure anyway.

So we’re stuck with some primary human needs and, as yet, no way to fill them. Many of us have traveled a continuum of spiritual communities and practices and found that none of them fit. My attempts to name cultural appropriation in the alternative culture have been largely met with hostility. For me, grief has given way to acceptance. The forces misdirecting attempts to “indigenize” Euro-Americans and other settlers/immigrants have been in motion since the Wandervogel. I will not be able to find or create an authentic and honorable spiritual practice or community in my lifetime. All I can do is lay out the problems as I see them and perhaps some guidelines and hope that, over time, something better emerges. It will take generations, but it’s not a project we can abandon.

Humans are hard-wired for spiritual ecstasy. We are hungry animals who need to be taught how to participate, respectfully and humbly, in the cycles of death and rebirth on which our lives depend. We’re social creatures who need behavioral norms to form and guide us if our cultures are to be decent places to live. We’re suffering individuals, faced with the human condition of loss and mortality, who will look for solace and grace. We also look for beauty. Soaring music produces an endorphin release in most people. And you don’t even need to believe in anything beyond the physical plane to agree with most of the above.

Some white people say they want to “reindigenize,” that they want a spiritual connection to the land where they live. That requires building a relationship to that place. That place is actually millions of creatures, the vast majority too small for us to see, all working together to create more life. Some of them create oxygen; many more create soil; some create habitat, like beavers making wetlands. To indigenize means offering friendship to all of them. That means getting to know them, their histories, their needs, their joys and sorrows. It means respecting their boundaries and committing to their care. It means learning to listen, which requires turning off the chatter and static of the self. Maybe then they will speak to you or even offer you help. All of them are under assault right now: every biome, each living community is being pulled to pieces, 200 species at a time. It’s a thirty-year mystery to me how the neopagans can claim to worship the earth and, with few exceptions, be indifferent to fighting for it. There’s a vague liberalism but no clarion call to action. That needs to change if this fledgling religion wants to make any reasonable claim to a moral framework that sacrilizes the earth. If the sacred doesn’t deserve defense, then what ever will?

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 5, 2018 | Lobbying

by Center for Biological Diversity

WASHINGTON— Defenders of Wildlife, along with the Center for Biological Diversity and Patagonia Area Resource Alliance, today filed a notice of intent to sue the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect the Patagonia eyed silkmoth under the Endangered Species Act.

The rare Patagonia eyed silkmoth is clinging to survival in only three isolated locations in Arizona and Mexico. The groups previously petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Service to list the moth under the Endangered Species Act and designate critical habitat for the species.

“The Patagonia eyed silkmoth is hanging by a thread. With the only U.S. population existing in an Arizona cemetery, where its only remaining food source could be wiped out by cattle, this species clearly needs federal protection to save it from extinction,” said Lindsay Dofelmier, legal fellow at Defenders of Wildlife. “The Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision to dismiss evidence supporting listing the Patagonia eyed silkmoth was arbitrary. By failing to provide adequate explanation for the decision and not allowing for a 12-month status review, the Fish and Wildlife Service put the species at risk. Listing the silkmoth and designating critical habitat provides the best chance for recovery.”

The Patagonia eyed silkmoth exists in a single U.S. location, in an Arizona cemetery less than half an acre in size. In Sonora, Mexico, it lives on two sky islands, higher elevation areas that are ecologically different from the lowlands surrounding them.

“The Patagonia eyed silkmoth needs endangered species protection now, so we can start the work of recovering this beautiful animal,” said Brian Segee, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. “The Endangered Species Act has saved more than 99 percent of plants and animals with its protection from extinction, and it can do the same for this rare moth.”

Cattle grazing was the primary historic cause of habitat loss for the moth and continues to play a major role in the precarious situation of the species. Mining and climate change also threaten to destroy the last vestiges of potential silkmoth habitat on both sides of the border. A catastrophic fire at critical times of the year, when the adults, eggs or larvae are out, could completely erase the moth from any of these remaining localities. Listing the silkmoth and designating critical habitat for the species offers its best chance of survival and recovery.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 1, 2018 | Indigenous Autonomy

by Laura Hobson Herlihy / Cultural Survival

The Miskitu Yatama (Yapti Tasba Masraka Nanih Aslatakanka/Children of the Mother Earth) organization remained silent during last week’s violent protests in Nicaragua, ignited by the government’s April 16, 2018 approval of social security reforms. Many Miskitu people on the Nicaraguan Caribbean coast claimed the Instituto Nicaragüense de Seguridad Social (INSS) reform was not their fight, as Miskitu fisherman and lobster divers were excluded from the national system of social security and would not retire with pensions. Yet, they were supportive of the larger issue of the protests — the end of the Ortega dictatorship.

The Yatama Youth Organization released a statement on April 25, 2018, a week after the protests began, affirming their solidarity with the Nicaraguan university students now calling for President Ortega to step down. That evening by phone, the long-term Yatama Director and Nicaraguan congressman Brooklyn Rivera framed Yatama’s fight solely within the framework of Indigenous rights. Rivera stated, “We are still fighting for the same rights we have always fought for.” The Miskitu leader mentioned their right to saneamiento (the removal of mestizo colonists from Indian lands), as stipulated by Nicaraguan law 445; elections by ley consuetudinaria (customary law) in the autonomous regions, as ruled by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights; and fortification of the autonomy process (law 28).

Like an elderly statesman, Brooklyn Rivera sounded hopeful that he could use his position as an opposition congressman in the National Assembly to advance Indigenous rights during the up-coming dialogue for peace with Ortega’s Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) government, to be mediated this Sunday by the Catholic Church and headed by Cardinal Leopoldo Brenes. The interviewer suggested that Yatama is well-positioned as an opposition party to the FSLN in the up-coming regional elections in November 2018. Rivera insisted, “Yatama will not enter any elections if there is not electoral reform first.”

Fraudulent Elections: A History of Violence

Yatama broke their alliance (2006-2014) with the Sandinistas, partially due to alleged electoral fraud during the 2014 regional elections. Indeed, Yatama claimed the FSLN stole the last three elections–the 2014 regional, the 2016 general, and the 2017 municipal elections. After each election, Yatama held peaceful marches but were met with force and attacked by the police, antimotines (riot police) sent from Managua, and the Juventud Sandinista (armed Sandinista youth gangs).

In the 2017 municipal elections, Yatama lost control of its remaining municipalities in the North (RACN) and South (RACS) Caribbean Autonomous Regions. Violence erupted in three towns along the coast. In Bilwi, the capital of the RACN, the police and riot police (antimotines) stood by watching as paramilitary Sandinista turbas (youth gangs) burned Yatama headquarters and radio Yapti Tasba to the ground, toppled the Indian statue in the town center, subverted the green Yatama flag with a black and red FSLN flag, and attempted to shoot Yatama leader Brooklyn Rivera, who escaped.

Police arrested one-hundred Yatama members and detained them in jail for more than a month. Like the university students recently persecuted by the FSLN in Managua, Yatama peaceful protestors were called ‘delincuentes’ and accused of looting stores and setting fires to public property. The state criminalized both groups of protestors–Yatama sympathizers and university students– to justify using force against them. Similarly, the state attacked, detained, disappeared, and murdered university students last week in Nicaragua. Captured and shared through social media, the vivid videos of government repression served to vindicate, support, and liberate the formerly criminalized Yatama protestors.

Yatama Reaction to Protests

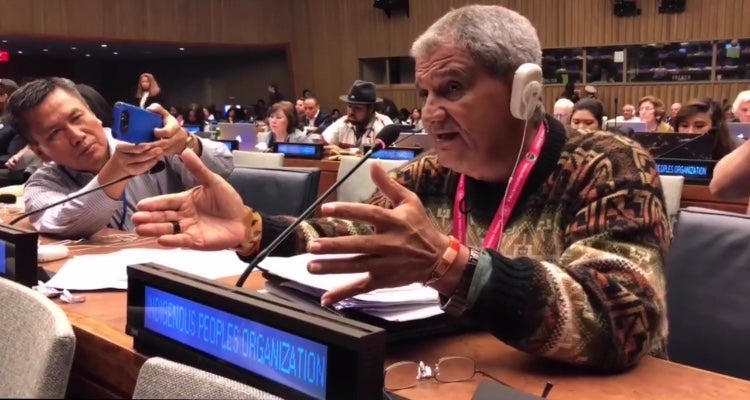

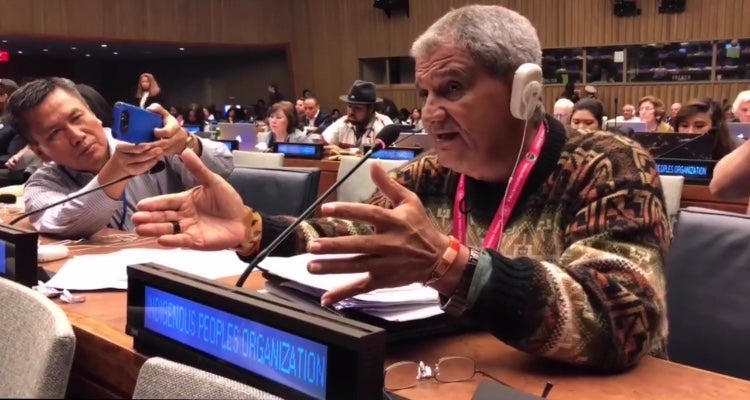

Yatama Director and Nicaraguan Congressman Brooklyn Rivera giving an intervention at the 2018 UNPFII

Yatama members remained glued to their smart phones and social media all week, watching university students fight and broader society organize massive protest marches in Managua. They replayed the video up-loads of the fall of Chayopalos, the metal trees of life placed across the capital that have come to symbolize the First Lady/Vice President Rosario Murillo’s overreaching power and the government’s wasteful spending of scarce resources. Like a dream come true, they envisioned the Ortega-Murillos stepping down from power.

Rivera was busy fighting for Indigenous and Afro-descendant rights at the 2018 United Nations Permanent Forum of Indigenous Issues in New York, when the protests began in Nicaragua. He commented in retrospect, “I was not surprised by the protests. The Nicaraguan people are tired of the Ortega regime.”

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 30, 2018 | Protests & Symbolic Acts

by Survival International

Thousands of indigenous people gathered in Brazil’s capital this week, to protest against plans to destroy their lands and lives.

The Indians, from tribes across the country, painted the streets with “blood,” marched through the city, demonstrated at government buildings, and called for their rights to be respected.

Sonia Guajajara, an indigenous leader and candidate for the Vice-Presidency in Brazil’s upcoming general election, said: “We are denouncing the genocide of our people…This is the most suffering we’ve experienced since the dictatorship. By staining the streets red, we are showing how much blood has been shed in our fight for the protection of indigenous lands… The fight goes on!”

The protest marks Brazil’s “Indigenous April” and follows the annual “Day of the Indian,” 19 April, when the country’s President often announces some progress in the protection of indigenous peoples’ ancestral lands. This year, no such announcements were made. Instead, it was reported that the head of the government’s Indigenous Affairs Department would be replaced, as he was not fulfilling the demands of anti-indigenous politicians and ranchers.

Politicians linked to the powerful agribusiness lobby are pushing through a series of laws and proposals which would make it easier for outsiders to steal indigenous peoples’ lands and exploit their resources.

This would be disastrous for tribes across the country, including the Guarani, who suffer one of the highest suicide rates in the world, as most of their land has been stolen for cattle ranching and soya, corn and sugarcane plantations.

Adalto Guarani told Survival International of the politicians’ plan: “Please help us destroy this! It’s like a bomb waiting to explode, and if it explodes, it will put an end to our very existence. Please give us a chance to survive.”

And uncontacted tribes, the most vulnerable peoples on the planet, could be wiped out if their lands are opened up. Tribes like the uncontacted Kawahiva and Awá are on the brink of extinction as they live on the run, fleeing violence from outsiders. But if their land is protected, they can thrive.

Survival International and its supporters in over 100 countries are working in partnership with tribes across Brazil to prevent their annihilation and the extinction of their uncontacted relatives.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 18, 2018 | Culture of Resistance

Editor’s note: The following is from the chapter “Culture of Resistance” of the book Deep Green Resistance: A Strategy to Save the Planet. This book is now available for free online.

by Lierre Keith / Deep Green Resistance

The alternative culture of the ’60s offered a generalized revolt against structure, responsibility, and morals. Being a youth culture, and following out of the Bohemian and the Beatniks, this was predictable. But a rejection of all structure and responsibility ends ultimately in atomized individuals motivated only by self interests, which looks rather exactly like capitalism’s fabled Economic Man. And a flat out refusal of the concept of morality is the province of sociopaths. This is not a plan with a future.

Take the pull of the alternative culture across the left. Now add the ugliness and the authoritarianism of the right’s “family values.” It’s no surprise that the left has ceded all claim to morality. But it’s also a mistake. We have values, too. War is a moral issue. Poverty is a moral issue. Two hundred species driven extinct every day is a moral issue. Underneath every instance of injustice is a violation of what we know is right. Unrestricted personal license in a context that abandons morals to celebrate outrage will not inspire a movement for justice, nor will it build a culture worth living in. It will grant the powerful more entitlements—for instance, the rich will get richer, and the poor will be conceptually nonexistent, except as a resource. “If it feels good, do it” isn’t even the province of adolescence; it’s the morality of a toddler. For the entitled individual, in whatever version—Homo economicus, Homo bohemicus, or Homo sadeus—pleasure is reduced to cheap thrills, while the deepest human joys—intimacy, belonging, participation from community to cosmos—are impossible. This is because those joys depend on a realization that we need other people and other beings, ultimately a whole web of existence, all of whom deserve our protection and respect. In return we get rewards, rewards that can accrue into profound satisfaction: from the contented joy of communal well-being to the animal ecstasy of sex to the grace of participation in the mystery.

Currently, the right places the blame for the destruction of both family and community at the feet of liberalism. The real culprit, of course, is capitalism, especially the corporate and mass media versions. But as long as the left refuses to fight for our values as values—and to enact those values in our lives and our movements—the right will be partially correct. They will also have recruitment potential that we’re squandering: people know that civic life and basic social norms have degenerated.

It is a triumph for capitalism that the right is winning the US culture war by pinning this decay of family and community on the left. But the right is willing to take a moral stance, even though the man behind the curtain isn’t Sodom or Gomorrah, it’s corporate capitalism. Meanwhile the left might identify capitalism as the problem, but by and large refuses a moral stance.

The US is dominated by corporate rule. The Democrats and Republicans are really the two wings of the Capitalist Party. Neither is going to critique the masters. It is up to us, the people who hold human rights and our living planet dear above all things, to speak the truth. We need to rise above individualism and live in the knowledge that we are the only people who are going to defend what is good in human possibility against the destructive overlapping power-grab of capitalism, patriarchy, and industrialization.

We can begin by picking up the pieces of community and civic life in the US. People of my parent’s generation are correct to mourn the loss of the community trust and participation that they once experienced. And as Robert Putnam makes clear in his book on the subject, Bowling Alone, social trust is linked to both civic and political participation in ways that are mutually reinforcing—or mutually reducing. My mother and her friends have the addresses of their state and federal congress-people memorized. Twenty years behind them, I at least know their names. And the current college-aged generation? They explain earnestly how the government works: “The President tells Congress what to do, and Congress tells the Supreme Court what to do.” In two generations, there goes every advance since Magna Carta.

We’re getting stupider, crueler, and more depressed by the minute. Oliver James calls the values of the corporate media “Affluenza,” likening it to a virus that spreads across societies. He points out that anxiety, depression, and addiction rise in direct proportion to the inequity in a country. The values required to institutionalize inequality are values that are destructive to human happiness and human community. Injustice requires reducing people—including ourselves—to “manipulable commodities.”74 James writes, “Intimacy is destroyed if you regard another person as an object to be manipulated to serve your ends, whether at work or at play.… This leaves you feeling lonely and craving emotional contact, vulnerable to depression.”75

How did this happen? When did people stop caring? One insight of Marxist cultural theorists like Antonio Gramsci is that in order for oppression to function smoothly, ideology must be transferred from the oppressors to the oppressed. They can’t stand over us all with guns twenty-four hours a day. This transfer must be consensual and actively embraced to work on a society-wide scale. If the dominant class can make the ideology pleasurable, so much the better. Nothing could have done the job better than the passivity-inducing, addictive, and isolating technologies of first television and then the Internet.

Corporations have managed to coerce a huge percentage of the population into abandoning the values and behaviors that make people happy—to act against our own interests by instilling in us a new mythos and a set of compulsive behaviors. There is no question that television and other mass media are addictive, leading to “habituation, desensitization, satiation, and an increasing level of arousal … required to maintain satisfaction.”76 Clearly, there is an intense short-term pleasure capturing people, because the long-term losses are tremendous. Literally thousands of studies have documented television’s damage to children; indeed, a coalition of professional groups, including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, put out a joint report in 2000 declaring media violence a serious public health issue to children, with effects that are “measurable and long-lasting.”77 The American Academy of Pediatrics reports, “Extensive research evidence indicates that media violence can contribute to aggressive behavior, desensitization to violence, nightmares, and fear of being harmed.”78 The most chilling studies link television to teen depression, eating disorders, and suicide. If the destruction of our young isn’t enough to get us to fight back, what will be? As a culture, we are actively handing over the young to be socialized by corporate America in a set of values that are essentially amoral. The average child will spend 2,000 hours with her parents and 40,000 hours with the mass media. Why even bother to have children?

If culture is a set of stories we collectively tell, the stories have now been reduced to the sound bites of profit, offered up in a tantalizing, addictive flash that barricades access to our selves, if not our souls. Writes Maggie Jackson, “The way we live is eroding our capacity for deep, sustained, perceptive attention—the building blocks of intimacy, wisdom, and cultural progress.”79 For the young, those barricades may be permanent. Children need to experience bonding or they will end up with personality disorders, living as narcissists, borderlines, and sociopaths. They must learn basic values like compassion, generosity, and duty to become functioning members of society. They must have brains that can learn, contemplate, and question in order to have both a rich internal life and to have something to offer as participants in a democracy. For the developing child, bonding, values, and expectations create neurologic patterns that last a lifetime. Their absence leaves voids that can never be filled. The brain gets one opportunity to build itself, and only one.

The job of a parent is to socialize the young. Until recently, parents and children were nestled inside a larger social system with the same basic values taught at home. Now, parents are being told to “protect” their kids from the culture at large—a task that cannot be done. Society is where we all live, unless you want to move to Antarctica. Even if you managed to keep the worst excesses of consumerist, violent, and misogynist elements out of your child’s immediate environment, the child still has to leave the house. If the culture is so toxic that we can’t entrust our children to it, we need to change the culture.

The values taught by the mass media encourage the worst in human beings. If people are objects, neither intimacy nor community are possible. If image is all we are, we will always need to be on display. Social invisibility is a kind of death to social creatures. We buy more and more, whether higher-status cars or lower-cut jeans, so that we can have a better shot at being noticed as the object du jour. People surrounded by a culture of mass images experience themselves and the world as depersonalized, distant, and fractured. This is the psychological profile of PTSD. Add to that the sexual objectification and degradation of those images, and you have girls presenting with PTSD symptoms with no history of abuse.80 The culture itself has become the perpetrator.

Yes, we can try to inoculate ourselves and our children against the mass media, both its messages and its processes. But why should anyone need to be protected from the culture in which they live? And what good are all your heartfelt conversations and empowering feminist fairy tales when your girl child is surrounded by people who are not fans of Gaia Girls, but Girls Gone Wild?

As Pat Murphy bravely writes,

Suggesting that media is in general harmful and should be eliminated (or a dramatic reduction in the time spent imbibing it) at first seems absurd. But it is no more absurd than suggesting the age of oil and other fossil fuels is over. Media, energy and corporate control have evolved together. We need different concepts and new world views to transition away from fossil fuels and its infrastructure of corporations (including those of the media).81

Again, the right does not have a monopoly on values. We can reject authoritarianism, conformity, social hierarchy, anti-intellectualism, and religious fundamentalism. We can defend equality, justice, compassion, intellectual engagement, civic responsibility, and even love against the corporate jihad. We have to.