by DGR News Service | Apr 8, 2021 | Alienation & Mental Health, Male Violence, Pornography, Women & Radical Feminism

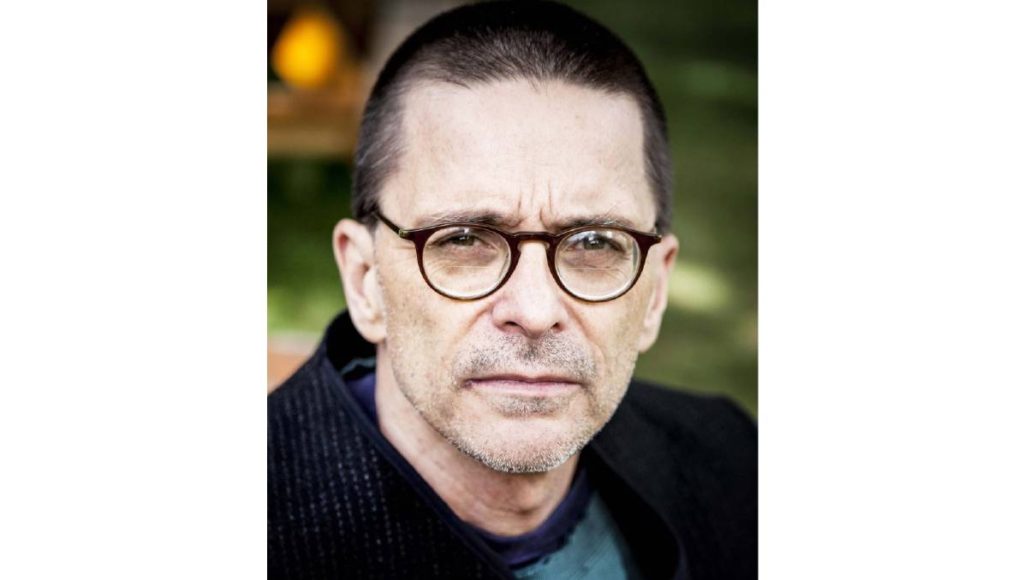

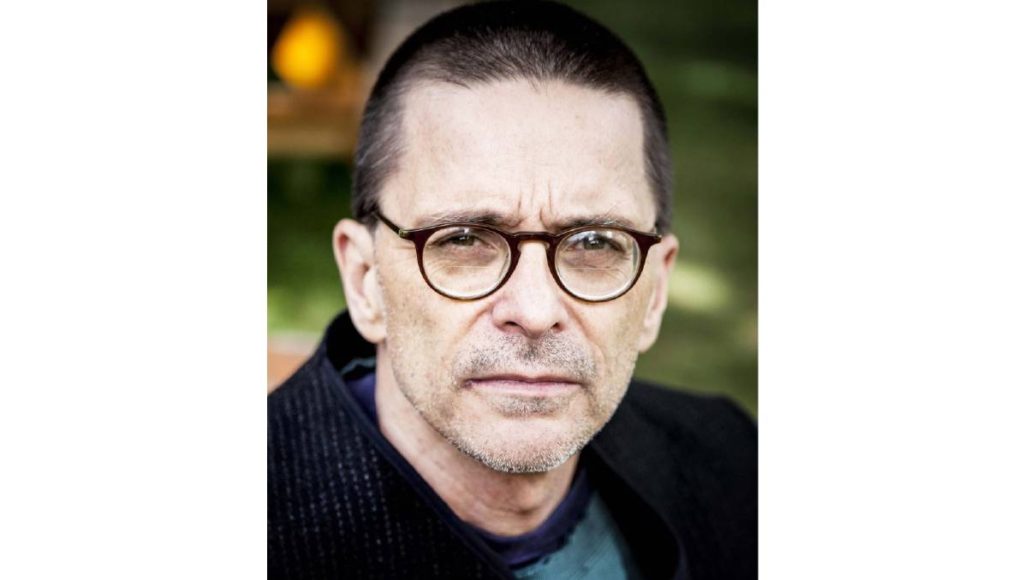

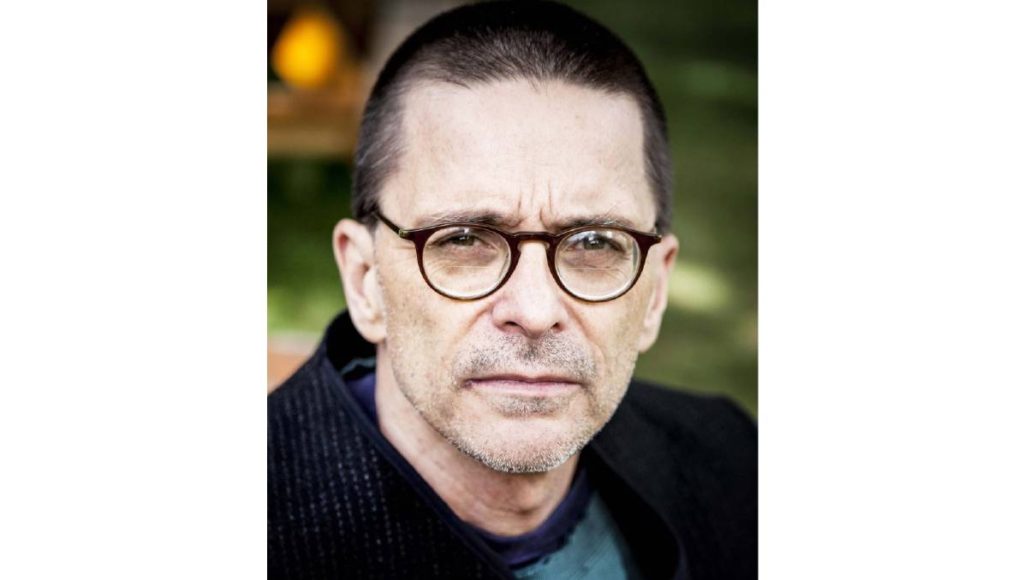

Robert Jensen is a rare and important example of a man embracing radical feministm. As radical feminist organisation, DGR encourages men to step up against patriarchy (and this neither means to be a man-hater nor a sexual prude). As Robert Jensen states below, “Our goal is the end of patriarchy by challenging the patriarchal practices that do so much damage to so many of us.”

This certainly includes pornography.

This article originally appeared on feministcurrent.

by Robert Jensen

Let’s start with the world according to pornographers:

Sex is natural. Pornography is just sex on film. Therefore, pornography is natural.

If you do not accept the obvious “logic” of that argument, you are a prude who is sex-negative.

Any questions?

But what about the intense misogyny in pornography?

You’re a prude.

But what about the explicit racism in pornography?

You’re sex-negative.

What about the physical and psychological injuries routinely suffered by women used in pornography?

You’re prudishly sex-negative.

What about the consequences of conditioning so many men’s arousal and experience of sexual pleasure to these sexist and racist images?

You’re sex-negatively prudish.

If your concerns about pornography flow from spirituality, you must be a religious nut.

If your concerns about pornography are based in feminism, you must be a man-hater.

Sadly, this is often how attempts to discuss the social problems flowing from the production and consumption of contemporary sexually explicit media play out—especially in conversations with liberal, progressive, and leftist men, and with some feminists who describe themselves as pro-porn or “sex positive.”

My goal is to mark those responses as diversions; focus on the content of pornography and its underlying ideology; examine why such material is so prevalent; and discuss why this matters for our attempts to create a truly sex-positive society that fosters meaningful autonomy for girls and women.

So, “pornographic distortions,” refers both to the ways in which pornography distorts human sexuality, and the way in which pornography’s defenders distort the views of critics. Let’s start with the latter.

Pornography’s critics

For the record, I am not a religious nut nor a man-hater.

I am a secular progressive Christian. By that, I mean that I was raised in a predominantly Christian culture, and the narratives and ethics of Christianity remain relevant in my life, even though I don’t accept all Christian doctrines and I long ago rejected the supernatural claims associated with a conventional interpretation of the faith tradition (i.e., a virgin birth and resurrection as historical facts, the possibility of miracles, the existence of a divine entity). But those stories and moral frameworks have influenced how I see the world, in conversation with many other philosophical and political traditions that I find helpful. I see no reason to ignore this aspect of my life.

I work from a radical feminist analysis of patriarchy. By that, I mean that I recognize institutionalized male dominance as morally unjust and not only an impediment to women’s freedom but to social justice more generally (that’s feminism), and central to patriarchy are men’s attempts to own or control women’s reproductive power and sexuality (that’s radical feminism). I see no reason to be afraid of that analysis.

In more than three decades of work in the feminist anti-pornography movement and the larger struggle against men’s violence and exploitation of women, I have worked with a wide range of people motivated by religion and/or feminism. I have met many lovely people, from a variety of backgrounds and with a wide range of experiences, who reject the pornography industry’s cynical approach to human sexuality and are committed to challenging the routine abuse of women in the sexual-exploitation industries. I have yet to meet someone who is a prude or sex-negative. Such people exist, of course, but they aren’t a part of the movement I am part of. Most of us in the anti-pornography movement struggle to understand the complexity of sexuality, which is true of most people I meet. Some of us in the movement have sexual histories marked by trauma, which also makes us pretty “normal,” given how routine sexual violence is in patriarchal cultures. Our goal is the end of patriarchy by challenging the patriarchal practices that do so much damage to so many of us. We struggle to make a truly sex-positive culture possible.

That’s as much time as I am willing to spend trying to persuade people that I’m not crazy or hateful. Let’s move on to the more important task of understanding how and why the pornography industry offers such a destructive picture of human sexuality.

The pornography industry

Let’s start with terminology. I used the term “sexual-exploitation industries” to include prostitution, strip clubs, massage parlors, and escort services, along with pornography and other mediated forms of commercial sex. Applying a feminist analysis, all of these enterprises are ways that men buy and sell objectified female bodies for sexual pleasure. Boys and vulnerable men are also exploited in these industries, but the majority of these businesses offer men the opportunity to buy women and girls.

Pornography is also a form of mass media. Applying a media analysis, we examine the production process, the stories being told, and audience reception. How is pornography made and who profits? What are the patterns and themes in pornographic images and stories? How do the consumers of pornography use the material in their lives and with what effects?

I’ll focus here on the content of pornography, but first let’s recognize the importance of understanding production and reception.

How is pornography made? Andrea Dworkin, the writer/activist so central to the feminist critique, always emphasized that what you see in pornography is not simulated sex. The sex acts being performed on a woman that appear to be uncomfortable or painful were done to a real woman. Did that woman choose that? In some sense yes, but under what conditions and with what other choices available? What constraints did she face in her life and what opportunities did she have? And whatever level of choice she made doesn’t change the nature of the injuries that women sustain. Before we even ask about women’s choices, we should focus on men: Why do men choose to use pornography that exploits women?

There are many different genres in pornography, but the bulk of the market is heterosexual sex marketed to heterosexual men, who use it as a masturbation facilitator. There is a long debate about the relationship of pornography use and sexual violence, a question with no simple answer. But, as advertisers have long observed, exposure to media messages can affect attitudes and attitudes shape behavior. We know that people, especially young people, are prone to imitating behaviors they see in mass media that are presented as fashionable or exciting. Consider the advice a university sex researcher offers to male students: “If you’re with somebody for the first time, don’t choke them, don’t ejaculate on their face, don’t try to have anal sex with them. These are all things that are just unlikely to go over well.” Why would such advice be necessary? Those acts are routine in pornography, and pornography is the de facto sex education for many boys and young men.

Pornographic images

My focus here is on pornographic images, specifically those produced by the heterosexual pornography industry. We’ll use a simple definition for pornography: Graphic sexually explicit material that is designed to produce sexual arousal, with a focus on material produced for men, who are the majority of the consumers. While women’s use of pornography has increased in recent years, the industry still produces material that reflects the male sexual imagination in patriarchy.

A bit of history is useful in understanding these images. The pornography industry operated largely underground until the 1960s and ‘70s, when it began being more accepted in mainstream society. That led to a sharp increase in the amount of pornography produced, a trend that expanded dramatically with new media technologies, such as VCRs, DVDs, and the internet.

The industry’s desire to increase profits drove the development of new products, in this case a wider variety of sexual acts in pornographic films. The standard sexual script in pornography — little or no foreplay, oral sex (primarily performed by women on men), vaginal intercourse, and occasionally anal intercourse — expanded to keep viewers from becoming satiated and drifting away. In capitalism, competition for market share produces “innovation,” though more often than not innovation means a slightly different version of products we didn’t need in the first place. In that sense, pornography is a quintessentially capitalist business.

The first of those changes was the more routine presentation of men penetrating women anally, in increasingly rough fashion. Why anal? One longtime pornography producer whom I interviewed at an industry trade show explained it to me in explicit language, which I’ll paraphrase. Men know that most women don’t want anal sex, he said. So, when men get angry at their wives and girlfriends, they think to themselves, “I’d like to fuck her in the ass.” Because they can’t necessarily do that in real life, he said, they love it in pornography.

That man didn’t realize he was articulating, in his own crude fashion, a radical feminist critique: pornography is not just sex on film but rather sex in the context of male domination and female subordination, the central dynamic of patriarchy. The sexual experience in pornography is made more intense with sex acts that men find pleasurable but women may not want.

Where did the industry go from there? As pornographers sought to expand market share and profit, they continued to innovate. Here are several pornographic sex practices — acts that are typically not part of most people’s real-world sex lives but are common in pornography — that followed the normalizing of anal sex:

- double penetration (two men penetrating a woman vaginally and anally at the same time);

- double vag (two men penetrating a woman vaginally at the same time);

- double anal (two men penetrating a woman anally at the same time);

- gagging (oral penetration of a woman so aggressive that it makes her gag);

- choking (men forcefully grasping a woman’s throat during intercourse, sometimes choking the woman); and

- ATM (industry slang for ass-to-mouth, when a man removes his penis from the anus of a woman and, without visible cleaning, inserts his penis into her mouth or the mouth of another woman).

Other routine acts in pornography include slapping and spitting on women, pulling women’s hair, and ejaculating on women’s bodies (long called “the money shot”), especially on their faces (what has come to be called a “facial”).

Even pornographers acknowledge that they can’t imagine what comes after all this. One industry veteran told me that everything that could be done to a woman’s body had been filmed. “After all, how many dicks can you stick in a girl at one time?” he said. A director I interviewed echoed that, wondering “Where can it go besides [multiple penetrations]? Every hole is filled.” Another director worried that pornography was going too far and that porn sex increasingly resembled “circus acts.” “The thing about it is,” he told me, “there’s only but so many holes, only but so many different types of penetration that can be executed upon a woman.”

One pornographic genre that explores other forms of degradation is called “interracial,” which has expanded in the past two decades. Films in this category can feature any combination of racial groups, but virtually all employ racist stereotypes (the hot-blooded Latina, sexually animalistic black women, demure Asian “geishas” who live to serve white men, immigrant women who are easily exploited) and racist language (I’ll spare you examples of that). One of the most common interracial scenes is a white woman being penetrated by one or more black men, who are presented as being rougher and more aggressive, drawing on the racist stereotype of black men as a threat to the purity of white women, while at the same time revealing the white woman to be nothing but a slut who seeks such defilement. This racism would be denounced in any other mass media form but continues in pornography with little or no objection from most progressives.

Finally, in recent years there has been an increase in what my friend Gail Dines calls “pseudo-child pornography.” Sexually explicit material using minors is illegal and is vigorously prosecuted, and so mainstream pornography stays away from actual child pornography. But the industry uses young-looking adult women in childlike settings (the classic image is a petite woman, almost always white, in a girls’ school uniform) to create the impression that an adult man can have the high school cheerleader of his fantasy. Another popular version features stepfathers having sex with a teenage stepdaughters. This material is not marketed specifically to pedophiles but is part of the mainstream pornography market for “ordinary” guys.

Dines’ summary of contemporary pornography captures these trends: “Today’s mainstream Internet porn is brutal and cruel, with body-punishing sex acts that debase and dehumanize women.”

Radical feminist critique

For those familiar with the radical feminist critique of pornography, these trends are not surprising. If the pornography is not just the presentation of explicit sex but rather sex in the patriarchal domination/subordination dynamic, then pornographers will find it profitable to sexualize any and all forms of inequality.

This analysis, developed within the larger feminist project of challenging men’s violence against women, was first articulated clearly by Andrea Dworkin, who identified what we can call the elements of the pornographic:

- Objectification: when “a human being, through social means, is made less than human, turned into a thing or commodity, bought and sold.”

- Hierarchy: “a group on top (men) and a group on the bottom (women).”

- Submission: when acts of obedience and compliance become necessary for survival, members of oppressed groups learn to anticipate the orders and desires of those who have power over them, and their compliance is then used by the dominant group to justify its dominance.

- Violence: “systematic, endemic enough to be unremarkable and normative, usually taken as an implicit right of the one committing the violence.”

Although there is variation in the thousands of commercial pornographic films produced over the years, the main themes have remained consistent: (1) All women always want sex from men; (2) women like all the sexual acts that men perform or demand, and; (3) any woman who resists can be aroused by force, which is rarely necessary because most of the women in pornography are the “nymphomaniacs” of men’s fantasies. While both men and women are portrayed as hypersexual, men typically are the sexual subjects, who control the action and dictate the terms of the sex. Women are the sexual objects fulfilling male desire.

The radical feminist critique demonstrates not only that almost all sexually explicit material is pornographic, in the sense of reflecting and reinforcing patriarchy’s domination/subordination dynamic, but that pop culture is increasingly pornified. Pornography is a specific genre, but those elements of the pornographic also are present in other media, including Hollywood movies, television shows, video games, and advertising.

Intimacy

Let’s ask a simple question the pornographers would prefer we ignore: What kind of intimacy is possible in a pornographic world? I don’t mean just in pornography, but in a world in which this kind of pornography is widely used and widely accepted. Let’s go back to the connection between media use and behavior, which is complex. Does repeated exposure to advertising lead us to buy products we would not otherwise buy? Do violent scenes in movies or video games lead to increased rates of violence in people with a predisposition for violence? Definitive judgments are difficult, but we know that stories have the power to shape attitudes and attitudes effect behavior. We know that orgasm is a powerful reinforcer. We have plenty of reasons to be concerned about how the sexist and racist messages in pornography might influence the attitudes and behavior of pornography consumers. And we have plenty of reasons to be concerned about how the normalizing of pornographic images throughout the culture might shape how we all relate to our own bodies and understand sexuality in ways we aren’t aware of.

That all seems obvious, but industry defenders continue to assert that pornography is just fantasy and we shouldn’t police people’s fantasies. They want us to believe that in this one realm of human life — the use of sexually explicit media as a masturbation facilitator, primarily for men — people are unaffected by the power of stories and images. Even if that implausible claim were true, we still should ask, why are these particular fantasies so popular? When pornographers entered the mainstream and faced fewer restrictions, why did they create so many fantasies around male domination and female subordination? Why did they sexualize racist fantasies? Why did they encourage adult men to fantasize about having sex with teenagers? Why are pornography’s fantasies so routinely cruel and degrading to women?

There isn’t a neat and clean separation of our imaginations and our actions, between what goes on in our heads and what we do in the world. Even if we don’t know exactly how mass-mediated stories and images — what the pornographers and their supporters want to label as “just fantasy” — affect attitudes and behavior, we have reasons to be concerned about contemporary pornography.

And following Andrea Dworkin, let’s also not forget the women used in pornography. For men to masturbate to a double-anal scene, a woman must be penetrated anally by two men at the same time. Do we care about that woman? Do we care about what ideas those men carry around in their head? Think back to the advice the sex educator gives to young men, counseling them to stop behaving the way that pornography taught them to behave. Do we care about the female partners of those men?

These are not problems of a few individuals. I’ve talked to many young women who have told me that when they were in middle school and high school, they conformed to boys’ pornographic notions of sex without realizing what was happening to them. Some of those same women have told me that they would prefer to date men who don’t use pornography but they’ve given up because such men are so hard to find. I’ve talked to many adult women who don’t want to ask their boyfriends or husbands whether they use pornography, or inquire about what kind of pornography they might use, because they are afraid of the answer. I’ve talked to gay men who say that some of the same problems exist in their community.

I’ve talked to a lot of men who defend their pornography use and are unwilling to stop. But in recent years I’ve talked with more men who realize the negative effects of using this pornography but find it hard to stop. They report compulsive, addictive-like use of pornography, sometimes to the point of being unable to function sexually with a partner. These men feel profoundly alienated from themselves, from their own bodies.

Heat and light

The radical feminist critique of the misogyny and racism in pornography isn’t about denying humans’ sexual nature. It is not about imposing a single set of sexual norms on everyone. It’s not about hatred of men. The critique of the domination/subordination dynamic in pornography is about the struggle to transcend the patriarchal sexuality of contemporary culture in search of a sexuality that connects people rather than alienates us from each other and from our own bodies.

I have no simple prescriptions for how to move forward, though I see no way forward without a radical feminist critique. We struggle for intimacy, for connection, for something that feels more authentic than the pornographic script. We can start by recognizing how we have all been socialized, whether through traditional religion or secular society or both, into patriarchal values. That’s bound to be painful — for men when we realize we’ve been trained to dominate sexually, and for women when they realize they have been trained to accept sexual subordination.

I will end with an idea I first articulated 25 years ago and continue to ponder. A common way people talk about sex in the dominant culture is in terms of heat: She’s hot, he’s a hottie, we had hot sex. In a world obsessed with hotness, we focus on appearances and technique — whether someone looks the way we are socialized to believe attractive people should look, and the mechanics of sex acts. We hope that the right look and the right moves will produce heat. Sex is all bump-and-grind — the friction produces the heat, and the heat makes the sex good.

But we should remember a phrase commonly used to describe an argument that is intense but which doesn’t really advance our understanding—we say that such an argument “produced more heat than light.”

Heat is part of life, but what if in our sexual activity, our search for intimacy and connection, we obsessed less about heat and thought more about light? What if instead of desperately seeking hot sex, we searched for a way to produce light when we touch? What if that touch could be about finding a way to generate light between people so that we could see ourselves and each other better?

If the goal is knowing ourselves and each other like that, then what we need is not really heat but light to illuminate the path. How do we touch and talk to each other to shine that light? I am hesitant to suggest strategies; there isn’t a recipe book for that, no list of sexual positions to work through so that we may reach sexual bliss. There is only the ongoing quest to touch and be touched, to be truly alive. James Baldwin, as he so often did, got to the heart of this in a comment that is often quoted and a good place to conclude:

“I think the inability to love is the central problem, because the inability masks a certain terror, and that terror is the terror of being touched. And, if you can’t be touched, you can’t be changed. And, if you can’t be changed, you can’t be alive.”

An edited version of this essay was recorded for presentation at the online Canadian Sexual Exploitation Summit hosted by Defend Dignity, May 6-7, 2021.

Robert Jensen is Emeritus Professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin and a founding board member of the Third Coast Activist Resource Center. He collaborates with the Ecosphere Studies program at The Land Institute in Salina, KS. Jensen is the author of The Restless and Relentless Mind of Wes Jackson: Searching for Sustainability; The End of Patriarchy: Radical Feminism for Men; Plain Radical: Living, Loving, and Learning to Leave the Planet Gracefully; Arguing for Our Lives: A User’s Guide to Constructive Dialogue; All My Bones Shake: Seeking a Progressive Path to the Prophetic Voice; Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity; The Heart of Whiteness: Confronting Race, Racism and White Privilege; Citizens of the Empire: The Struggle to Claim Our Humanity; and Writing Dissent: Taking Radical Ideas from the Margins to the Mainstream.

Jensen is host of “Podcast from the Prairie” with Wes Jackson and associate producer of the forthcoming documentary film Prairie Prophecy: The Restless and Relentless Mind of Wes Jackson.

Jensen can be reached at rjensen@austin.utexas.edu. Follow him on Twitter: @jensenrobertw

by DGR News Service | Feb 17, 2021 | Male Supremacy, Male Violence, Pornography

Robert Jensen (no relation to Derrick Jensen) is a very important and rare example of a man embracing radical feminism. Originally published in feminist current, you can read the original here!

When a European graduate student emailed to ask if I would participate in an assignment to “do an interview with one of my favourite authors,” I said yes. My books have not exactly been best-sellers, and so I was an easy target for anyone describing me as a “favourite author.”

But beyond my gratitude for someone noticing my writing, I was intrigued by the questions. And when I suggested we might publish the interview, I was even more intrigued by the student’s request to stay anonymous. She wrote that she was “extremely unsure of having my name on anything online. I know I am very strange (probably the strangest person I’ve ever met), but I’m not on Facebook or social media. I actually like the fact that googling my name gets no results about me. I don’t know if I’m ready yet to give up my blissful online non-existence. Is that crazy?”

It didn’t seem crazy to me, but I asked if she might want to describe herself for readers. Here is her self-description:

“I am a classically trained musician (more comfortable playing an instrument than talking in front of people), specializing in linguistics and interested in the meaning and the realities behind words and actions. Born and raised in a communist country, clandestinely listening to Radio Free Europe while growing up, having all civil liberties seriously infringed, yet being raised free by amazing parents (with the help of books and music) who knew how to help us find our identity independently of society’s impositions. I have always been profoundly enraged by any form of injustice or lie, and from a very young age I would routinely get in trouble for standing up for and defending my beliefs and people who were being abused in some way or another (something that has always been puzzling to adults and authority figures, since I am extremely shy and well behaved). I got myself almost expelled in high school for refusing to participate in an event which contradicted who I am. And I do not work on Sundays.

Seeing how the world keeps collapsing and becoming more insane, I began to think that maybe I am insane for wanting a better world than the one that’s become so normalized. Stumbling upon Robert Jensen’s books made me realize I am not the only ‘insane’ person in the world. It takes courage to pursue a path that others ignore or deny, to talk about things that others so politically correctly sweep under the rug, to want to face your fears and the pain that comes with admitting the truth, and to give a voice to the pain, fear, and humiliation of those dehumanized by our lack of humanity.”

Here is the interview, conducted over email, last month:

~~~

Who is Robert Jensen? How would you describe yourself?

Robert Jensen: I’m a simple boy from the prairie. That’s how I started describing myself when I found myself in so many places that I would have never imagined when I was growing up. I was born and raised in North Dakota with modest aspirations. I was a good student, in that well-behaved, diligent, and just slightly above average way that made teachers happy. I did what I was told and never caused trouble. I didn’t come from an intellectual or political background, and I wasn’t gifted. So, when I found myself with a Ph.D., teaching at a big university, publishing books, and politically active in feminism and the left — which involved a lot of traveling, including internationally for the first time in my life — it was all a bit hard to comprehend. I used to call a friend when I was on the road and ask, “How did a boy from Fargo, ND, end up here?” I continue to think that “I’m a simple boy from the prairie” is a pretty accurate description of me.

What was your childhood like? Were you a happy child? What are your best and worst memories from that time?

RJ: I am still searching for the words to use in public to describe my childhood. My family life was defined by the trauma of abuse and alcoholism. I spent my early years perpetually terrified and was pretty much alone in dealing with that terror. So, no, I was not a happy child. I don’t have a lot of clear memories of that time, which is one way the human mind deals with trauma, to repress conscious memories of it. I think one reason that a radical feminist critique of men’s violence and sexual exploitation resonated with me was that it provided a coherent framework to understand not only society but also my own experience. I came to see that what happened in my family was not an aberration from an otherwise healthy society but one predictable outcome of a very unhealthy society.

Which authors have been important in helping you understand that?

RJ: I gave a lecture once in which I identified the most important writers in my intellectual and political development: Andrea Dworkin (feminism), James Baldwin (critiques of white supremacy), Noam Chomsky (critiques of capitalism and imperialism), and Wes Jackson (ecological analysis). There are countless other writers who have been crucial in my development, but those are my anchors, the people who first opened up new ways of thinking about the world for me. They helped me understand not only specific issues they wrote about but how it all fits together, a coherent critique of domination.

Radical feminism is central in your writing. What is radical feminism?

RJ: Feminism is both an intellectual and a political enterprise — that is, it is an analysis and critique of patriarchy, and a movement to challenge the illegitimate authority that flows from patriarchy. Most feminist work focuses on men’s domination and exploitation of women, but feminism also should be a consistent rejection of the domination/subordination dynamic that exists in many other realms of life, most notably in white supremacy, capitalism, and imperialism. I think radical feminism accomplishes that most fully. Radical feminism identifies the centrality of men’s claim to own or control women’s reproductive power and women’s sexuality, whether through violence or cultural coercion. Radical feminism helped me understand how deeply patriarchy is woven into the fabric of everyday life and how central it is to the domination/subordination that defines the world. Here’s how I put it in a recent article:

“For thousands of years — longer than other systems of oppression have existed—men have claimed the right to own or control women. That does not mean patriarchy creates more suffering today than those other systems — indeed, there is so much suffering that trying to quantify it is impossible — but only that patriarchy has been part of human experience longer. Here is another way to say this: White supremacy has never existed without patriarchy. Capitalism has never existed without patriarchy. Imperialism has never existed without patriarchy.”

What is it like being a male radical feminist in a world dominated by the idea that “men rule,” standing up in front of men and telling them that they should stop being men?

RJ: My message isn’t that men should stop being men. A male human can’t stop being a male human, of course. But we can reject the concept of masculinity in patriarchy, which trains us to seek dominance. When people critique “toxic masculinity,” a popular phrase in the United States these days, I suggest that “masculinity in patriarchy” is more accurate. The most overtly abusive and toxic forms of masculinity should be eliminated, obviously, but so should the “benevolent sexism” that also is prevalent in patriarchy. My argument to men is simple: If we struggle to transcend masculinity in patriarchy, we can shift the obsessive focus on “how to be a man” to the more useful question of how we can be decent human beings.

What is your definition for “human being”? What about “woman,” and “man” (not as constructed by patriarchy)?

RJ: I would say that we all have to struggle to become fully human in societies that so often reward inhumanity. I don’t have a definition so much as a list of things that most of us want — a deep sense of connection to others that doesn’t undermine the exploration of our individuality; outlets for the creativity that is part of being human, which takes many different forms depending on the individual; a secure community that doesn’t demand that we suppress what makes each of us different. In other words, being human is balancing the need for commitment to a community in which we can feel safe and loved, and the equally important need for individual expression. I think that’s pretty much the same for women and men. But in patriarchy, all of that hardens into the categories of masculine (dominant) and feminine (subordinate). In that system, it’s hard for anyone to become fully human.

You speak of the advantages of being a “white man in a heterosexual relationship, holding a job that pays more than a living wage for work I enjoy, living in the United States.” What are the disadvantages of all that?

RJ: I don’t know that I would call it a disadvantage, but I think most of us who have unearned privilege and power — whether we acknowledge it or not — know we don’t deserve it, which generates in many of us a fear that whatever success we’ve had is a sham. And when we fail, the sense of entitlement leads us too often to blame that failure on others. But on the scale of troubles in this world, that doesn’t rate very high. There’s a reactionary argument in the United States that in an age of multiculturalism, somehow it is white men who are the real oppressed minority, which is just silly. My whole life I have had subtle advantages that came because the people who ran the world I lived and worked in typically looked like me and cut me breaks, often in ways I wasn’t even aware of. I have listened to a lot of mediocre white guys whine about how tough it is for them. My response is, “As a mediocre white guy myself, I can testify to how easy we have it.” When I say that I’m mediocre, I’m not being glib. Like anyone, I have various skills, but I am not exceptional in anything. I think by accepting that fact about myself, that I’m pretty average, I have been able to develop the skills I have to the fullest rather than constantly trying to prove that I’m exceptional. I used to tell students that the secret to my success was that I was mediocre, and I knew it, and so I could make the best of it. That makes it easy to be grateful for all the opportunities I’ve had.

Lately I have come across the term “ethical porn,” described as “ethical, stylish and elegant sexual adult entertainment” (“female and couple focused online porn”). Is there such a thing as pornography that is ethical? The descriptions on one of those sites state: “beautiful tasteful… very naughty photographic collections” which “show much more focus on the pleasure of passion and hot-blooded sex. The desire for sensual female arousal, with a balanced and more realistic approach to sexual gratification with more equal pleasure… porn for women that provided real meaningful and beautiful relatable sex.” Yet the whole idea, the action, and the actual techniques are exactly the same as “classic porn.” Isn’t pornography just pornography, anti-human, no matter how you do it?

RJ: We can start by recognizing that pornography produced without abusing women is better than pornography in which such abuse is routine. Pornography that doesn’t present women being degraded for men’s pleasure is better than the mainstream pornography that eroticizes men’s domination of women. But lots of questions remain, as you point out. Why does so much of the so-called ethical or feminist pornography look so similar to mainstream pornography? And, even more important, is it healthy to embrace a patriarchal culture’s obsession with getting sexual pleasure through the mediated objectification of others? In other words, one question is, “What is on the screen in pornography?” and the other is, “Why is the sexuality of so many people so focused on screens?” If through sexuality we seek not only pleasure but intimacy and connection to another person, why do we think explicit pictures will help? Do those images provide the kind of pleasure that we really want? For me, the answer is no. I don’t think graphic sexually explicit images would enhance the kind of connection my partner and I value. I realize other people come to other conclusions, but I think everyone would benefit from reflecting on what we lose when so much of life — including intimacy — is mediated, coming to us through a screen.

What are the most important qualities (virtues) of a human being? What are a person’s flaws/failings that can make you run away as far and fast as possible?

RJ: I think that when we see our own flaws in others, we are the most critical of them. So, I can’t stand people who come to judgment quickly without listening to another person long enough. In other words, I am acutely aware of how often I lack patience. The thing I value most in others, which is probably true for almost all of us, is the capacity for empathy. The older I get, the easier it has been to understand my own failings, and I hope that makes me more empathetic toward others.

What advice would you give children, especially boys, not just about masculinity and femininity but about life more generally today?

RJ: I would start by recognizing that what we do is usually more important than what we say. Adults can tell children what we believe, but kids watch us to see if we act in a way consistent with those statements. For example, I would suggest that kids experience the world directly as often as possible and be wary of letting screens — computers, video games, television — define their lives. That advice is meaningful only if I model the same behavior. It’s important to tell children not to be limited by patriarchal gender norms, but it’s even more important to avoid reinforcing those norms in everyday life.

What advice would you give young adults, or for that matter, any adult?

RJ: When I was teaching, I found myself repeating, over and over again, three things: “Both things are true;” “Reasonable people can disagree;” and “We’re all the same, and there’s a lot of individual variation in the human species.” The first is about recognizing complexity. In my media law class, for example, I would point out that an expansive conception of freedom of speech is essential to democracy, and at the same time it’s crucial that we punish some kinds of speech (libel, harassing speech in certain circumstances, threats) because speech can cause tangible harms that we want to prevent. Both things are true. The second recognizes that in assessing the complexity, we are bound to come to different conclusions and should work to understand why and not assume the other person is an idiot. The third is a reminder that we are one species and all pretty much the same, yet no two of us are exactly alike. None of those three observations are particularly deep; they’re really just truisms. But we need to be reminded of them often.

With all that has happened these past months — all those lives and livelihoods wasted to hate, racism, injustice, COVID-19, with the elections and the surrounding events — does it seem that people have learnt something from all this? Is there more empathy, more understanding, more humanity? Because from everything I see around the world, it looks like we are even more numb, asleep, and unaware, less caring, even more selfish and superficial than before.

RJ: Like always, there’s good news and bad news on that front. It’s not hard to find examples of people turning away from our shared humanity and seeking a sense of superiority and dominance, examples of greed intensifying in the face of so much deprivation. It’s also easy to find people doing exactly the opposite, taking risks to try to bring into existence a society in which empathy is the norm and resources are shared equitably. That’s just a reminder that human nature is variable and plastic — there’s a wide range of expressions of our nature, and individuals can change over time. But at this moment in the United States, it’s hard to be upbeat. Politicians routinely say two things that indicate how deeply in denial as a society we are about all this. One is, in response to the latest horror, “this is not who we are as a nation,” when it is of course a part of who we are as a nation, though some want to ignore that. The other is “there’s nothing we can’t accomplish when we work together,” which is just plain stupid. There are biophysical limits that no society can ignore indefinitely, though the modern consumer capitalist economy encourages us to ignore that reality. The ecological crises we face, including but not limited to rapid climate change, are a result of the species ignoring those limits, with the United States leading the way.

What does the future look like for our planet, for humanity? Is there any hope for us?

RJ: Let’s start with what’s fairly clear: There is no hope that a population of eight billion people with the current level of aggregate consumption today can continue indefinitely. It’s important to recognize that this consumption isn’t equally distributed, and that injustice has to be corrected. But we have to face the reality that high-energy/high-technology societies are unsustainable no matter how things are distributed. The end of the current economic and political systems will likely be in this century, maybe a lot sooner than we expect, and no one knows what will come after that. My summary of the future is “fewer and less.” There will be fewer people consuming a lot less energy and resources, and planning should focus on how to make such a future as humane as possible. Most people — even on the left or in the environmental movement — do not want to face that, at least in part because no one has a plan for how to get from where we are today to a sustainable human population with a sustainable level of consumption. But that’s the challenge. As a species, we likely will fail. But that doesn’t mean we stop trying to figure it out. We’re not going to save the world as we know it, but the intensity of human suffering and ecological destruction can be reduced.

Are the arts important for you in this struggle? Do you have a favourite musician(s)? Movies? Novels?

RJ: For a lot of people, the arts are important in coping with these realities. I am not very artistically inclined, either in talent or interests. I like to watch movies and read novels now and then, and I listen to music. But as I got older, I gravitated toward a focus on more straight-forward political and intellectual work. That said, I have two favourite singer/songwriters. One is John Gorka, whom I first heard decades ago, and I immediately fell in love with the stories in his songs. I own everything he has recorded. The second is Eliza Gilkyson. I heard one of her records in the mid-1980s and liked it but didn’t follow her career. In 2005, I met her at a political event in Austin, TX, where we both lived, and we got to be friends. I started listening to her CDs and was especially struck by the quality of her songwriting, as well as her voice. The friendship turned into a romantic relationship and we’re married now. It turned out that she and John were friends, and lately they have been teaching songwriting workshops together. I’m in the enviable position of knowing my two favourite musicians, both of whom have an incredible gift with words, of making the human experience — both the political and personal sides of life — come alive in songs.

Anything you would like to talk about, but people do not usually ask or do not want to hear.

RJ: In interviews, we tend to focus on what makes us look good. We tell a story that sounds coherent, but real life is messy. I like it when people ask me about mistakes I’ve made, stupid things I’ve done, ideas I once believed in that I now reject. There are lots of examples of that in my personal life, of course. But I’m thinking specifically of how long it took me to come to the critical analysis of the domination/subordination dynamic. In my mid-20s, I had a period of several years in which I was a harsh libertarian and a fan of the writing of Ayn Rand. At one point, I think I owned every book she had written. Looking back, I think I understand why. There’s a lot of attention, positive and negative, paid to Rand’s celebration of greed and wealth, but that was never my attraction to her books. I never wanted to be rich or find a justification for being greedy. I think she’s popular with lots of disaffected young people — the kind of person I was in my 20s — because she promises a life without emotional complexity. Rand constructs the perfect individual as a creature who chooses all relationships rationally, which describes no one who has ever lived, herself included. It’s just not the kind of animals we are. We are born into community and cannot make sense of ourselves as individuals outside of community. Her books offer the illusion that we can, by force of individual will, escape all the messiness of living with others. It’s interesting that Rand’s personal life was a train wreck, I suspect because she believed in those illusions and never really accepted the kind of creatures we human beings are. My assumption is that she was so scared of some aspects of the real world — perhaps the pain of loss and rejection — that she took refuge in the fantasy world she created. I think that’s a good reminder of how fear can drive us all to an irrational place if we let it. Anyway, when I started to understand that, I drifted away from Rand’s writing and started constructing a worldview that allowed me to face not only my own fears but also the collective fears of the culture, instead of running from them.

~~~

Robert Jensen is Emeritus Professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin and a founding board member of the Third Coast Activist Resource Center. He collaborates with the Ecosphere Studies program at The Land Institute in Salina, KS.

Jensen can be reached at rjensen@austin.utexas.edu. To join an email list to receive articles by Jensen, go to http://www.thirdcoastactivist.org/jensenupdates-info.html. Follow him on Twitter: @jensenrobertw

by DGR News Service | Nov 5, 2020 | Education, Gender

In this article, Robert Jensen shares a straight-forward view of Cancel Culture and how critique of a political position is not necessarily directed to mock the people who hold it but rather an invitation to become accountable to one’s obligation to participate in democratic dialogue.

Originally published on Feminist Current.

Being Canceled

In the current squabble on the liberal/progressive/left side of the fence over so-called “cancel culture,” in which one open letter in favor of freedom of expression led to a rebuttal open letter in favor of a different approach to freedom of expression, I can offer a report on the experience of being canceled.

Several times over the past few years I’ve been asked to speak by university or community groups, only to see those events canceled by organizers after someone complained that I am “transphobic.” At a couple of events that drew complaints but were not canceled, including one in a church, critics tried to disrupt my talk. None of the events was actually a talk on transgender issues. The complaint was that I should not be allowed to speak in progressive settings — about other feminist issues, the ecological crises, or anything else — because what I’ve written about the ideology of the transgender movement is said to be bigoted. A local radical bookstore that denounced me publicly went so far as to no longer carry my books, which I had given them free copies of for years.

If I were, in fact, a bigot, these cancellations would be easy to understand. I have never invited a bigot to speak in a class I taught or at an event I helped organize. I have invited people to speak who held some political views with which I did not agree (after all, if I only invited people who agreed with me on everything, I would be bored and lonely), but I have no interest in giving bigots a public platform.

The curious thing about these canceled/disrupted events is that no one ever pointed to anything I have written or said in public that is, in fact, bigoted. If transphobia is the fear or hatred of people who identify as transgender, nothing I have written or said is transphobic. Most of my critics simply assert that because I support the radical feminist critique of transgender ideology, I am by definition a bigot and transphobe.

For the Sake of Clarity

Let me be clear: I’m not whining or asking for sympathy. I am a white man and a retired university professor with a stable income and a network of friends and comrades who offer support. I continue to do political and intellectual work I find rewarding and can find places to publish my work. While I don’t enjoy being insulted, these verbal attacks don’t have much effect on my life. I’m not concerned about myself but about the progressive community’s capacity for critical thinking and respectful debate.

In that spirit, here is my contribution to that debate on transgenderism and the value of open discussion:

One of the basic points that feminists — along with many other writers — have made is that biological sex categories are real and exist outside of any particular cultural understanding of those categories. The terms “male” and “female” refer to those biological sex categories, while social norms about “masculinity” and “femininity” reflect how any particular society expects males and females to behave. That may seem obvious to many readers, but in some progressive and feminist circles it’s routine for people to say that those sex categories themselves are a “social construction.” I have been told that because I assert that biological sex categories are immutable, I am transphobic.

Is that claim defensible? Are sex categories a social construction?

About Reproduction & Respiration

Let’s think about reproduction. Some creatures reproduce asexually, through such processes as fission and budding, and some animals lay eggs. Most mammals, including all humans, reproduce sexually through the combination of a sperm and an egg (the two types of gamete cells) that leads to live birth.

Now, let’s think about respiration. Most aquatic creatures (whales and dolphins, which are mammals, are an exception) take in oxygen through gills. Mammals, including all humans, get oxygen by taking air into our lungs.

These descriptions of creatures’ reproduction and respiration are the result of a social process we call science, but they are not social constructions. We describe the world with human language, but what we describe doesn’t change just because we might change the language we use.

The term “social construction” implies that a reality can change through social processes. An example is marriage. What is a marriage? That depends on how a particular society constructs the concept. Change the definition — to include same-sex couples, for example — and the reality of who can get married changes.

Cannot Be Changed by Human Action

But again, at the risk of seeming simplistic, these descriptions of reproduction and respiration systems cannot be changed by human action. We cannot socially construct ourselves into reproducing asexually or by laying eggs instead of reproducing sexually through fertilization of egg by sperm, any more than we could socially construct ourselves into breathing through gills instead of lungs.

When it comes to respiration, no one suggests that “lung-based respiration is a social construction.” If someone made such a claim most of us would say, “I’m sorry, but that doesn’t make any sense to me.” Yet when it comes to reproduction, some people argue that “biological sex is a social construction,” which makes no more sense than claiming respiration is a social construction.

To be clear: Humans do create cultural meaning about sex differences. Humans who have a genetic makeup to produce sperm (males) and humans who have a genetic makeup to produce eggs (females) are treated differently in a variety of ways that go beyond roles in reproduction. [Note: A small percentage of the human population is born “intersex,” a term to mark those who do not fit clearly into male/female categories in terms of reproductive systems, secondary sexual characteristics, and chromosomal structure. But the existence of intersex people does not change the realities of sexual reproduction, and they are not a third sex.]

The Radical Change

In the struggle for women’s liberation, feminists in the 1970s began to use the term “gender” to describe the social construction of meaning around the differences in biological sex. When men would say, “Women are just not suited for political leadership,” for example, feminists would point out that this was not a biological fact to be accepted but a cultural norm to be resisted.

To state the obvious: Biological sex categories exist outside of human action. Social gender categories are a product of human action.

This observation leads to reasonable questions, which are not bigoted or transphobic: When those in the transgender movement assert that “trans women are women,” what do they mean? If they mean that a male human can somehow transform into a female human, the claim is incoherent because humans cannot change biological sex categories. If they mean that a male human can feel uncomfortable in the social gender category of “man” and prefer to live in a society’s gender category of “woman,” that is easy to understand. But it begs a question: Is the problem that one is assigned to the wrong category? Or is the problem that society has imposed gender categories that are rigid, repressive, and reactionary on everyone? And if the problem is in society’s gender categories, then is not the solution to analyze the system of patriarchy — institutionalized male dominance — that generates those rigid categories? Should we not seek to dismantle that system? Radical feminists argue for such a radical change in society.

These are the kinds of questions I have asked and the kinds of arguments I have made in writing and speaking. If I am wrong, then critics should point out mistakes and inaccuracies in my work. But if this radical feminist analysis is a strong one, then how can an accurate description of biological realities be evidence of bigotry or transphobia?

An Approach, Not An Attack

When I challenge the ideology of the transgender movement from a radical feminist perspective, which is sometimes referred to as “gender-critical” (critical of the way our culture socially constructs gender norms), I am not attacking people who identify as transgender. Instead, I am offering an alternative approach — one rooted in a collective struggle against patriarchal ideologies, institutions, and practices, rather than a medicalized approach rooted in liberal individualism.

That’s why the label “TERF” (trans-exclusionary radical feminism) is inaccurate. Radical feminists don’t exclude people who identify as transgender but rather offer what we believe is a more productive way to deal with the distress that people feel about gender norms that are rigid, repressive, and reactionary. That is not bigotry, but politics. Our arguments are relevant to the ongoing debate about public policies, such as who is granted access to female-only spaces or who can compete in girls’ and women’s sports. They are relevant to concerns about the safety of puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgical interventions. And radical feminism is grounded in compassion for those who experience gender dysphoria — instead of turning away from reality, we are suggesting ways to cope that we believe to be more productive for everyone.

Now, a final prediction. I expect that some people in the transgender movement will suggest that my reproduction/respiration analogy mocks people who identify as transgender by suggesting that they are ignorant. Let me state clearly: I do not think that. The analogy is offered to point out that an argument relevant to public policy doesn’t hold up. To critique a political position in good faith is not to mock the people who hold it but rather to take seriously one’s obligation to participate in democratic dialogue.

In a cancel culture, people who disagree with me may find it easy to ignore the argument and simply label me a bigot, on the reasoning that because I think the ideology of the transgender movement is open to critique, I obviously am transphobic.

But I want to make one final plea that people not do that, with two questions: If my argument is cogent — and there certainly are good reasons to reach that conclusion — why is it in the interests of anyone — including people who identify as transgender — to ignore such an argument? And how can people determine whether my argument is cogent if it is not part of the public conversation?

You can find the original article here.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Mar 2, 2019 | Agriculture

by Fred Iutzi and Robert Jensen / Resilience.org

Propelled by the energy of progressive legislators elected in the 2018 midterms elections, a “Green New Deal” has become part of the political conversation in the United States, culminating in a resolution in the U.S. House with 67 cosponsors and a number of prominent senators lining up to join them. Decades of activism by groups working on climate change and other ecological crises, along with a surge of support in recent years for democratic socialism, has opened up new political opportunities for serious discussion of the intersection of social justice and sustainability.The Green New Deal proposal—which is a resolution, not a bill, that offers only a broad outline of goals and requires more detailed legislative proposals—will not be successful right out of the gate; many centrist Democrats are lukewarm, and most Republicans are hostile. This gives supporters plenty of time to consider crucial questions embedded in the term: (1) how “Green” will we have to get to create a truly sustainable society, and (2) is a “New Deal” a sufficient response to the multiple, cascading economic/ecological crises we face?

In strategic terms: Should a Green New Deal limit itself to a reformist agenda that proposes programs that can be passed as soon as possible, or should it advance a more revolutionary agenda aimed at challenging our economic system? Should those of us concerned about economic justice and ecological sustainability be realistic or radical?

Our answer—yes to all—does not avoid tough choices. The false dichotomies of reform v. revolution and realistic v. radical too often encourage self-marginalizing squabbles among people working for change. Philosophical and strategic differences exist among critics of the existing systems of power, of course, but collaborative work is possible—if all parties can agree not to ignore the potentially catastrophic long-term threats while trying to enact limited policies that are possible in the short term. Reforms can take us beyond a reformist agenda when pursued with revolutionary ideals. Radical proposals are often more realistic than policies crafted out of fear of going to the root of a problem.

Our proposal for an agricultural component for a Green New Deal offers an example of this approach. Humans need a revolutionary new way of producing food, which must go forward with a radical critique of capitalism’s ideology and the industrial worldview. Reforms can begin to bring those revolutionary ideas to life, and realistic proposals can be radical in helping to change worldviews.

We focus here on two proposals for a Green New Deal that are politically viable today but also point us toward the deeper long-term change needed: (1) job training that could help repopulate the countryside and change how farmers work, and (2) research on perennial grain crops that could change how we farm. Two existing organizations, the Land Stewardship Project in Minnesota and The Land Institute in Kansas, offer models for successful work in these areas.

Philosophy and Politics

We begin by foregrounding our critique of capitalism and the industrial worldview. All policy proposals are based on a vision of the future that we seek, and an assessment of the existing systems that create impediments to moving toward that vision. In a politically healthy and intellectually vibrant democracy, policy debates should start with articulations of those visions and assessments. “Pragmatists”—those who appoint themselves as guardians of common sense—are quick to warn against getting bogged down in ideological debates and/or talk of the future, advising that we must focus on what works today within existing systems. But accepting that barely camouflaged defense of the status quo guarantees that people with power today will remain in power, in the same institutions serving the same interests. It is more productive to debate big ideas as we move toward compromise on policy. Compromise without vision is capitulation.

Green New Deal proposals should not only offer a set of specific policy proposals but also articulate a new way of seeing humans and our place in the ecosphere. At the core of our worldview is the belief that:

- People are not merely labor-machines in the production process or customers in a mass-consumption economy. Economic systems must create meaningful work (along with an equitable distribution of wealth) and healthy communities (along with fulfilled individuals).

- The more-than-human world (what we typically call “nature”) cannot be treated as if the planet is nothing more than a mine for extraction and a dump for wastes. Economic systems must make possible a sustainable human presence on the planet.

These two statements of values are a direct challenge to capitalism and the industrial worldview that currently define the global economy. Fueled by the dense energy in coal, oil, and natural gas, industrial capitalism has been the most wildly productive economic system in human history, but it routinely fails to produce meaning in people’s lives and it draws down the ecological capital of the planet at a rate well beyond replacement levels. Most of the contemporary U.S. political establishment assumes these systems will continue in perpetuity, but Green New Deal advocates can challenge that by speaking to how their proposals meet human needs for meaning-in-community and challenge the illusion of infinite growth on a finite planet.

The Countryside

In an urban society and industrial economy dominated by finance, many people do not think of agriculture as either a significant economic sector or a threat to ecological sustainability. With less than two percent of the population employed in agriculture, farming is “out of sight, out of mind” for most of the population. To deal effectively with both economic and ecological crises, a Green New Deal should include agricultural policies that (1) support smaller farms with more farmers, living in viable rural economies and communities, and (2) advance alternatives to annual monoculture industrial farming, which is a major contributor to global warming and the degradation of ecosystems.

These concerns for the declining health of rural communities and ecosystems are connected. Economic and cultural forces have made farming increasingly unprofitable for small family operations and encouraged young people to view education as a vehicle to escape the farm. The command from the industrial worldview was “get big or get out,” and the not-so-subtle hint to young people has been that social status comes with managerial, technical, and intellectual careers in cities. The economic drivers have encouraged increasingly industrialized agriculture, adding to soil erosion and land degradation in the pursuit of short-term yield increases. The dominant culture tells us that markets know best and advanced technology is always better than traditional methods.

Today one hears of how rural America and its people are ignored, but a more accurate term would be exploited—an “economic colonization of rural America.” Agricultural land is exploited, as are below-ground mineral and water resources, typically in ecologically destructive fashion. Meanwhile, recreation areas are “preserved,” largely for use by city people. The damage done to land and people are, in economists’ vocabulary, externalities—rural people, the land, and its creatures pay costs that are not factored into economic transactions. Responding to the crises in rural America is crucial in any program aimed at building a just and sustainable society.

Farmer Training

Much of the discussion about job training/retraining for a Green Economy focuses on technical skills needed for solar-panel installation, weatherizing homes, etc.—important projects that are politically realistic, culturally palatable, and technologically mature today. But a sustainable future with dramatic reductions in fossil-fuel consumption also requires a redesigned agricultural system, which requires more people on the land. We need the appropriate “eyes-to-acres ratio” that makes it possible to farm in an ecologically responsibly manner, according to Wes Jackson, co-founder of The Land Institute and a leader in the sustainable agriculture movement.

A visionary Green New Deal proposal would, as a first step, provide support for programs to expand farming and farm-related occupations in rural areas, part of a long-term project to repopulate the countryside in preparation for the more labor-intensive sustainable agriculture that we would like to see today and will be necessary for a future with “land-conserving communities and healthy regional economies,” to borrow from The Berry Center. The dominant culture equates urban with the progressive and modern, and rural with the unsophisticated and backward, a prejudice that must be challenged not only in the world of ideas but also on the ground.

The Land Stewardship Project offers a template, with three successful training programs. A four-hour Farm Dreams workshop helps people clarify their motivations to farm and begins a process of identifying resources and needs, with help from an experienced farmer. In farmer-led classroom sessions, on-farm tours, and an extensive farmer network, the Farm Beginnings course is a one-year program designed for prospective farmers with some experience who are ready to start a farm, whether or not they currently own land. The two-year Journeyperson course supports people who have been managing their own farm and need guidance to improve or expand their operation for long-term success.

There are, of course, many other farm-training programs from non-profits, governmental agencies, and educational institutions. We highlight LSP, which was founded in 1982, because of its track record and flexibility in responding to political conditions and community needs, particularly its willingness to engage critiques of white supremacy. Support for such programs is not only sensible policy but, in blunt political terms, a signal that progressives backing a Green New Deal recognize the need to revitalize rural areas, where people often feel forgotten by urban legislators and their constituents.

Perennial Polycultures

There has been growing interest in community-supported agriculture, urban farms, and backyard gardening, all of which are components of a healthy food system and healthy communities but do not address the central challenges in the production of the grains (cereals, oilseeds, and pulses) that are the main staples of the human diet. Natural Systems Agriculture research at The Land Institute—which focuses on perennial polycultures (grain crops grown in mixtures of plants) to replace annual monoculture grain farming—offers a model for the long-term commitment to research and outreach necessary for large-scale sustainable agriculture.

Annual plants are alive for only part of the year and are weakly rooted even then, which leads to the loss of precious soil, nutrients, and water that perennial plants do a better job of holding. Monoculture approaches in some ways simplify farming, but those fields have only one kind of root architecture, which exacerbates the problem of wasted nutrients and water. Current industrial farming techniques (use of fossil-fuel based fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides, with increasingly expensive and complex farm implements) that are dominant in the developed world, and spreading beyond, also are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. Less disturbance of soil carbon, in tandem with reduced fossil fuel use in production, reduces the contribution of agriculture to global warming.

Founded in 1976, TLI’s long-term research program has developed Kernza, an intermediate wheatgrass now in limited commercial production, and is working on rice, wheat, sorghum, oilseeds, and legumes, in collaborations with people at 16 universities in the United States and in 18 other countries. Through this combination of perennial species in a diverse community of plants, “ecological intensification” can enhance fertility and reduce weeds, pests, and pathogens, supplanting commercial inputs and maintaining food production while reducing environmental impacts of agriculture.

A visionary Green New Deal could fund additional research into perennial polycultures and other projects that come under the heading of agro-ecology, an umbrella term for farming that rejects the reliance on the pesticides, herbicides, and chemical fertilizers that poison ecosystems all over the world.

Revolution in the Air?

Expanding the number of farmers with the skills needed to leave industrial agriculture behind, and developing crops for a low-energy world are crucial if we are to achieve an ecologically sustainable agriculture. But those changes are of little value without land on which those new farmers can raise those new crops. There is no avoiding the question of land ownership and the need for land reform.

We have no expertise in this area and no specific proposals to offer, but we recognize the importance of the question and the challenge it presents to achieving sustainability in the contemporary United States, as well as around the world. Today, land ownership patterns are at odds with our stated commitment to justice and sustainability—too few people own too much of the agricultural land, and women and people of color are particularly vulnerable to what a Food First report described as, “the disastrous effects of widespread land grabbing and land concentration.”

In somewhat tamer language, the USDA-supported Farmland Information Center reports what is common knowledge in the countryside: “Finding affordable land for purchase or long-term lease is often cited by beginning and expanding farmers and ranchers as their most significant challenge.” Adding to the problem is the loss of farmland to development; in a 2018 report, the American Farmland Trust reported that almost 31 million acres of agricultural land was “converted” between 1992 and 2012.

No one expects any bill introduced in today’s Congress to endorse government action to protect agricultural land from development and redistribute that land to prospective farmers who are currently landless—growing support for democratic socialism does not a revolution make. But any serious long-term planning will have to address land reform, for as the agrarian writer Wendell Berry points out, “There’s a fundamental incompatibility between industrial capitalism and both the ecological and the social principles of good agriculture.”

A vision of rural communities based on family farms is often mistakenly dismissed as mere nostalgia for a romanticized past. We can take stock of the past failures not only of the capitalist farm economy but also of farmers—small family farms are no guarantee of good farming, and rural communities do not guarantee social justice—and still realize that repopulating the countryside is an essential part of a sustainable future.

Conclusion

We began with a faith that people with shared values might disagree about strategies yet still work together. People working on a wide variety of other projects—for example, worker/producer/consumer cooperatives and land trusts—can find reasons to support our ideas, just as we support those projects. But we also recognize that real-world proposals have to prioritize, and so we want to be clear about differences.

For example, the Green New Deal resolution calls for “100 percent of the power demand in the United States through clean, renewable, and zero-emission energy sources.” One of the key groups backing the plan, the Sunrise Movement, calls this one of the three pillars of its program. We believe this is unrealistic. No combination of renewable energy sources can power the United States in its current form. To talk about renewable energy as a solution without highlighting the need for a dramatic decrease in consumption in the developed world is disingenuous. Pretending that we can maintain First World affluence and achieve sustainability will lead to failed projects and waste limited resources.

Many advocates of a Green New Deal focus on renewable energy technologies and other technological responses to rapid climate disruption and ecological crises. These technologies are only part of the solution. We should reject the dominant culture’s “technological fundamentalism”—the illusion that high-energy/high-technology can magically produce sustainability at current levels of human population and consumption. A Green New Deal should support technological innovations, but only those that help us move to a low-energy world in which human flourishing is redefined by improving the quality of relationships rather than maintaining the capacity for consumption.

We understand that short-term policy proposals must be “reasonable”—that is, they must connect to people’s concerns and be articulated in terms that can be widely understood. But they also must help move us toward a system that many today find impossible to imagine: An economy that not only (1) transcends capitalism and its wealth inequality but also (2) rejects the industrial worldview and its obsession with production. Today’s policy proposals should advance egalitarian goals for the economy but also embrace an ecological worldview for society, without turning from the difficulty posed by the dramatic changes that lie ahead.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 17, 2018 | Gender

For radical feminists, gender is understood as not merely a subjective internal sense of self; patriarchal gender norms are a product of culture, imposed on people and limiting everyone’s humanity.

by Robert Jensen / Feminist Current

I am routinely described as cisgender (defined as people whose internal sense of gender identity matches their biological sex). Because I have critiqued the ideology of the transgender movement, I also am often labeled a TERF (trans-exclusionary radical feminist). But neither term is accurate — I don’t self-identify as cisgender or as exclusionary.

Instead, I identify as an adult male who rejects the rigid, repressive, and reactionary gender norms of patriarchy, and I believe that radical feminism offers the most compelling analysis of a patriarchal sex/gender system. The feminist critique I embrace is not an attack on, nor an exclusion of, anyone who suffers from gender dysphoria or identifies as transgender, but rather offers an alternative framework for understanding patriarchy’s sex/gender system and challenging those patriarchal gender norms.

I used “patriarchy/patriarchal” four times in the last paragraph for emphasis: From a radical feminist perspective, nothing in sex/gender politics makes sense except in the light of patriarchy. (I borrow that formulation from the late evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky, who said, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”)

“Patriarchy,” from Greek meaning “rule of the father,” can be narrowly understood as the organization of a human community (from a family to a larger society) that gives a male ruler dominance over other men, and overall gives men control over women. More generally, the term marks various systems of institutionalized male dominance.

In her 1986 book, The Creation of Patriarchy, the late historian Gerda Lerner defined patriarchy as “the manifestation and institutionalization of male dominance over women and children in the family and the extension of male dominance over women in the society in general.” Patriarchy implies, she continued, “that men hold power in all the important institutions of society and that women are deprived of access to such power. It does not imply that women are either totally powerless or totally deprived of rights, influence and resources.” The specific forms patriarchy takes differ depending on time and place, “but the essence remains: some men control property and hold power over other men and over most women; men or male-dominated institutions control the sexuality and reproduction of females; most of the powerful institutions in society are dominated by men.”

In today’s world, patriarchy comes in forms both deeply conservative (such as Saudi Arabia) and superficially liberal (the United States), and the laws and customs of patriarchal societies vary. But at the core of patriarchy is men’s claim to control — sometimes even to own—women’s reproductive power and sexuality. In patriarchy, men make claims on, and about, women’s bodies that are at the core of assigning women lesser value in society.

Radical feminists, therefore, focus on the fight for women’s reproductive rights, and against men’s violence and sexual exploitation of women. As feminists from various traditions have long argued, it’s crucial to distinguish between biological sex categories and cultural gender norms.