by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Apr 21, 2013 | ANALYSIS, Mining & Drilling

By Joshua Headley / Deep Green Resistance New York

We ought not at least to delay dispersing a set of plausible fallacies about the economy of fuel, and the discovery of substitutes [for coal], which at present obscure the critical nature of the question, and are eagerly passed about among those who like to believe that we have an indefinite period of prosperity before us. –William Stanley Jevons, The Coal Question (1865)

There are, at present, many myths about green energy and its efficiency to address the demands and needs of our burgeoning industrial civilization, the least of which is that a switch to “renewable” energy will significantly reduce our dependency on, and consumption of, fossil fuels.

The opposite is true. If we study the actual productive processes required for current “renewable” energies (solar, wind, biofuel, etc.) we see that fossil fuels and their infrastructure are not only crucial but are also wholly fundamental to their development. To continue to use the words “renewable” and “clean” to describe such energy processes does a great disservice for generating the type of informed and rational decision-making required at our current junction.

To take one example – the production of turbines and the allocation of land necessary for the development, processing, distribution and storage of “renewable” wind energy. From the mining of rare metals, to the production of the turbines, to the transportation of various parts (weighing thousands of tons) to a central location, all the way up to the continued maintenance of the structure after its completion – wind energy requires industrial infrastructure (i.e. fossil fuels) in every step of the process.

If the conception of wind energy only involves the pristine image of wind turbines spinning, ever so wonderfully, along a beautiful coast or grassland, it’s not too hard to understand why so many of us hold green energy so highly as an alternative to fossil fuels. Noticeably absent in this conception, though, are the images of everything it took to get to that endpoint (which aren’t beautiful images to see at all and is largely the reason why wind energy isn’t marketed that way).

Because of the rapid growth and expansion of industrial civilization in the last two centuries, we are long past the days of easy accessible resources. If you take a look at the type of mining operations and drilling operations currently sustaining our way of life you will readily see degradation and devastation on unconscionable scales. This is our reality and these processes will not change no matter what our ends are – these processes are the degree with which “basic” extraction of all of the fundamental metals, minerals, and resources we are familiar with currently take place.

In much the same way that the absurdities of tar sands extraction, mountaintop removal, and hydraulic fracturing are plainly obvious, so too are the continued mining operations and refining processes of copper, silver, aluminum, zinc, etc. (all essential to the development of solar panels and wind turbines).

It is not enough – given our current situation and its dire implications – to just look at the pretty pictures and ignore everything else. All this does, as wonderfully reaffirming and uplifting as it may be, is keep us bound in delusions and false hopes. As Jevons affirms, the questions we have before us are of such overwhelming importance that it does no good to continue to delay dispersing plausible fallacies. If we wish to go anywhere from here, we absolutely need uncompromising (and often brutal) truth.

A common argument among proponents of supposed “green” energy – often prevalent among those who do understand the inherent destructive processes of fuels, mining and industry – is that by simply putting an end to capitalism and its profit motive, we will have the capacity to plan for the efficient and proper management of remaining fossil fuels.

However, the efficient use of a resource does not actually result in its decreased consumption, and we owe evidence of that to William Stanley Jevons’ work The Coal Question. Written in 1865 (during a time of such great progress that criticisms were unfathomable to most), Jevons devoted his study to questioning Britain’s heavy reliance on coal and how the implication of reaching its limits could threaten the empire. Many covered topics in this text have influenced the way in which many of us today discuss the issues of peak oil and sustainability – he wrote on the limits to growth, overshoot, energy return on energy input, taxation of resources and resource alternatives.

In the chapter, “Of the economy of fuel,” Jevons addresses the idea of efficiency directly. Prevalent at the time was the thought that the failing supply of coal would be met with new modes of using it, therefore leading to a stationary or diminished consumption. Making sure to distinguish between private consumption of coal (which accounted for less than one-third of total coal consumption) and the economy of coal in manufactures (the remaining two-thirds), he explained that we can see how new modes of economy lead to an increase of consumption according to parallel instances. He writes:

The economy of labor effected by the introduction of new machinery throws laborers out of employment for the moment. But such is the increased demand for the cheapened products, that eventually the sphere of employment is greatly widened. Often the very laborers whose labor is saved find their more efficient labor more demanded than before.

The same principle applies to the use of coal (and in our case, the use of fossil fuels more generally) – it is the very economy of their use that leads to their extensive consumption. This is known as the Jevons Paradox, and as it can be applied to coal and fossil fuels, it so rightfully can be (and should be) applied in our discussions of “green” and “renewable” energies – noting again that fossil fuels are never completely absent in the productive processes of these energy sources.

We can try to assert, given the general care we all wish to take in moving forward to avert catastrophic climate change, that much diligence will be taken for the efficient use of remaining resources but without the direct questioning of consumption our attempts are meaningless. Historically, in many varying industries and circumstances, efficiency does not solve the problem of consumption – it exasperates it. There is no guarantee that “green” energies will keep consumption levels stationary let alone result in a reduction of consumption (an obvious necessity if we are planning for a sustainable future).

Jevons continues, “Suppose our progress to be checked within half a century, yet by that time our consumption will probably be three or four times what it now is; there is nothing impossible or improbable in this; it is a moderate supposition, considering that our consumption has increased eight-fold in the last sixty years. But how shortened and darkened will the prospects of the country appear, with mines already deep, fuel dear, and yet a high rate of consumption to keep up if we are not to retrograde.”

Writing in 1865, Jevons could not have fathomed the level of growth that we have attained today but that doesn’t mean his early warnings of Britain’s use of coal should be wholly discarded. If anything, the continued rise and dominance of industrial civilization over nearly all of the earth’s land and people makes his arguments ever more pertinent to our present situation.

Based on current emissions of carbon alone (not factoring in the reaching of tipping points and various feedback loops) and the best science readily available, our time frame for action to avert catastrophic climate change is anywhere between 15-28 years. However, as has been true with every scientific estimate up to this point, it is impossible to predict that rate at which these various processes will occur and largely our estimates fall extremely short. It is quite probable that we are likely to reach the point of irreversible runaway warming sooner rather than later.

Suppose our progress and industrial capitalism could be checked within the next ten years, yet by that time our consumption could double and the state of the climate could be exponentially more unfavorable than it is now – what would be the capacity for which we could meaningfully engage in any amount of industrial production? Would it even be in the realm of possibility to implement large-scale overhauls towards “green” energy? Without a meaningful and drastic decrease in consumption habits (remembering most of this occurs in industry and not personal lifestyles) and a subsequent decrease in dependency on industrial infrastructure, the prospects of our future are severely shortened and darkened.

BREAKDOWN is a biweekly column by Joshua Headley, a writer and activist in New York City, exploring the intricacies of collapse and the inadequacy of prevalent ideologies, strategies, and solutions to the problems of industrial civilization.

Photo by Andreas Gücklhorn on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 10, 2012 | ANALYSIS, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change

By Mongabay

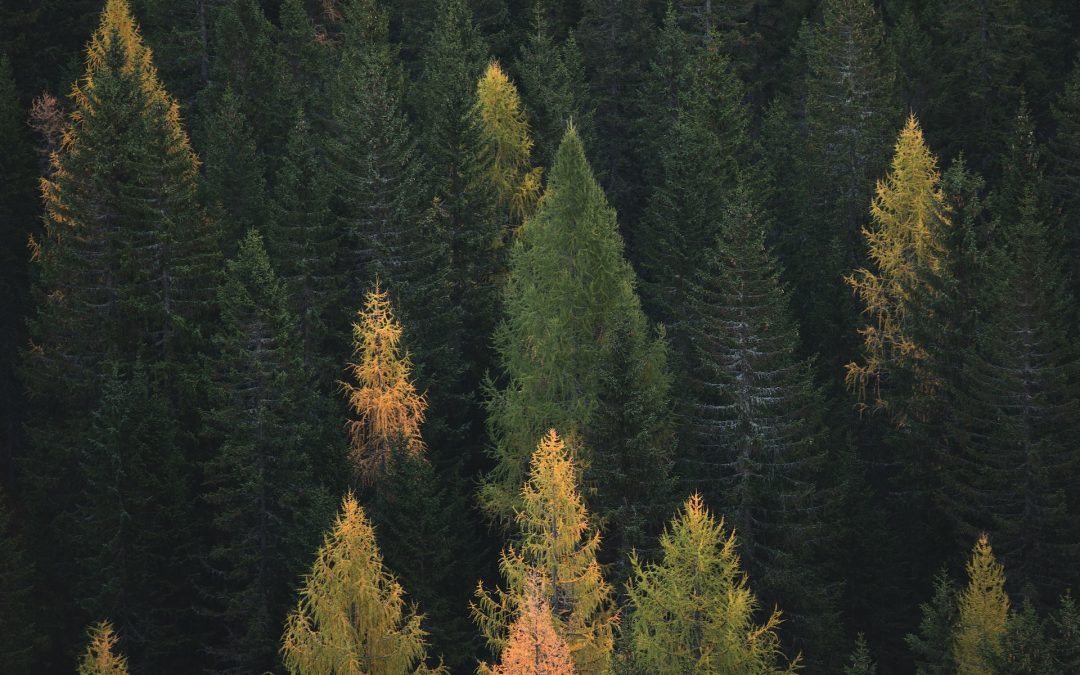

Already facing an onslaught of threats from logging and conversion for agriculture, forests worldwide are increasingly impacted by the effects of climate change, including drought, heightened fire risk, and disease, putting the ecological services they afford in jeopardy, warns a new paper published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The study, authored by William Anderegg of Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford University and Jeffrey Kane and Leander Anderegg of Northern Arizona University, reviews dozens of scientific papers dealing with the ecological impacts of climate change. They find widespread cases of forest die-off from drought and elevated temperatures, which can increase the incidence of fire and pest infestations like pine beetles. These effects have the potential to trigger transitions to other ecosystems, including scrubland and savanna. But the impacts vary from forest to forest and the authors say more research is needed to fully understand the effects of climate change on forest ecosystems.

However it is not only forests that are affected by climate change — they themselves impact climate. Forests store 45 percent of the carbon found in terrestrial ecosystems and sequester as much as 25 percent of annual carbon emissions from human activities, helping mitigate a key driver of climate change. Yet they also raise local temperate by absorbing sunlight. Clearing forests in polar regions has the paradoxical effect of increasing the reflectivity of Earth’s surface, reducing local temperatures. Yet clear-cutting of forests in the tropics accounts for 8-15 percent of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

The authors say that the research gaps make it difficult to forecast the economic and ecological impacts of climate change on forests, which cover cover some 42 million square kilometers or 30 percent of Earth’s land surface and underpin hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars a year in economic activity.

“The varied nature of the consequences of forest mortality means that we need a multidisciplinary approach going forward, including ecologists, biogeochemists, hydrologists, economists, social scientists, and climate scientists,” said William Anderegg in a statement. “A better understanding of forest die-off in response to climate change can inform forest management, business decisions, and policy.”

From Mongabay: “Climate change causing forest die-off globally”

Photo by Federico Bottos on Unsplash

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 22, 2012 | ANALYSIS, Mining & Drilling

By Dahr Jamail, Al Jazeera

Oil touches nearly every single aspect of the lives of those in the industrialised world. Most of our food, clothing, electronics, hygiene products and transportation simply would not exist without this resource.

There is a reason why oil giants such as ExxonMobile, BP, Total and Royal Dutch Shell, year in and year out, generate more profit than most other companies on the planet.

Our current global economy is based on continual growth, and that growth depends on cheap energy.

“Fossil fuels are roughly 84 per cent of what we use, and oil is 35 per cent of the world’s primary consumption energy,” says David Hughes, a geoscientist who studied Canada’s energy resources for nearly four decades.

Given that oil plays such a critical role in the world’s economy, one would deduce it would be important to know how much is left. Otherwise, the world’s stock markets would be exposed to fossil fuels, which would pose a grave risk to investors facing down a so-called carbon bubble, which could potentially dwarf the housing bubble and current debt crisis.

But acquiring accurate figures on the oil reserves of many of the member states of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is currently impossible, as this remains one of their most highly guarded state secrets.

OPEC, which currently has 12 member countries, established a quota system 25 years ago, so that the size of a country’s oil production quota was based on the size of its reserves.

This caused most Gulf countries to announce that their reserves were much larger than previously, and other OPEC members followed suit, according to Tom Whipple, an energy expert and former CIA analyst.

“Most outside observers believe that the ‘official’ reserves of OPEC members are way overstated,” Whipple, who is also a Post Carbon Institute fellow, told Al Jazeera. “Remember the last increase was in response to the OPEC quota agreement which allowed members to sell oil in proportion to their reserves – the bigger your reserves, the bigger your quota.”

“There have been many scandals over the years from people overstating reserves to make them look richer and more important than they are,” added Whipple.

“The biggest fuss I can recall was in Kuwait about five years ago, when somebody leaked a secret government study that said Kuwait’s reserves were less than half what they had been saying. After much fuss, the government made the whole issue even more secret and refused to answer further questions about the report.”

Oil giant BP produces an annual statistical review containing a spreadsheet that has reported world oil reserves back to 1980.

“I’ve tracked that review for the world and for specific OPEC countries,” geoscientist Hughes told Al Jazeera. “Six countries account for more than 80 per cent of OPEC oil; Saudi [Arabia], Kuwait, Iraq, Iran, United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela, and all six of them jacked up their reserves by nearly 100 per cent between 1984 and 1988.”

According to Hughes, this occurred at roughly the same time these countries changed how they set their production quotas.

“Since then, using Saudi [Arabia] as an example, their reported reserves have been flatlined since 1988, so they’ve not changed their reserves at all, but they produced 96 billion barrels of oil between 1980 and 2010.”

Both Hughes and Whipple, along with other energy experts, believe several OPEC countries are intentionally underreporting their reserves – a situation that will, sooner or later, lead to an economic crash.

State secrets

According to OPEC, “more than 80 per cent of the world’s proven oil reserves are located in OPEC member countries, with the bulk of OPEC oil reserves in the Middle East, amounting to 65 per cent of the OPEC total”.

The group’s website states:

“According to current estimates, OPEC member countries have made significant additions to their oil reserves in recent years … As a result, OPEC’s proven oil reserves currently stand at well above 1,190 billion barrels.”

According to OPEC, its member countries have added 347.2 billion barrels to their total proven crude oil reserves.

OPEC claims to maintain the ability to meet forecasted demand growth “for decades to come” and estimates their “ultimately recoverable reserves (URR)” have increased over time due to technological advances, enhanced recovery methods and new reservoir development.

But according to Hughes, key OPEC oil producers such as Iraq, Kuwait, UAE, and Iran have all likely hit their production peaks, and have been producing at the same levels ever since.

“Iraq[‘s production] is nearly flatline since 1988, and its peak production year was 1979. Kuwait has largely flatlined since 1988 and its peak production was 1972,” he said.

Hughes said that UAE had largely maintained the same level of production since 1988, while having a recent peak in 2006. Iran had a flat production level from 1988 to 2000, with just a slight increase in their reserves, albeit having reached peak production in 1974.

Venezuela, in contrast, nearly doubled its reserves in 2008, and increased them further in 2009, but, like the aforementioned, reached a production peak in 1970 that has not been attained since.

Hence, the leading OPEC countries, which account for two-thirds of the world’s oil reserves, have all passed their peak production points.

“Even Saudi [Arabia] peaked in 2005,” added Hughes, “What that tells you is their rate of production is a lot more important than what they report as their reserves. How can you produce nearly 100bn barrels, like Saudi, and your reserves don’t change at all?”

Hughes then added what he feels is the bottom-line.

“It’s likely those reserves are far lower than they are reporting.”

Dr Ali Samsam Bahktiari, a former official at the National Iranian Oil Company, said in 2006 – just a year before his death – that all the countries in the Middle East vastly overestimated or overstated their reserves.

Complicating matters, demand for oil is forecast to increase dramatically in coming decades.

Dr Fatih Birol, Chief Economist of the International Energy Agency, told The Independent on August 3, 2009:

“Even if demand remained steady, the world would have to find the equivalent of four Saudi Arabias to maintain production, and six Saudi Arabias if it is to keep up with the expected increase in demand between now and 2030. It’s a big challenge in terms of the geology, in terms of the investment and in terms of the geopolitics “

Furthermore, Whipple believes OPEC quotas are no longer relevant.

“Everybody just produces as much oil as they can or [that] is prudent to extract without damaging their oil fields,” he said. “The Saudi and Iranian fields are getting really old and should start to decline in the next decade. The Saudis just announced that they will not be increasing their capacity, except for natural gas. A lot of people are starting to lump in their natural gas production along with their conventional oil. It is called ‘barrels of oil equivalent’. Exxon has been doing this for years, as they pretend their output is increasing.”

Like Whipple, Hughes believes the true oil reserve totals for many OPEC members “are state secrets”.

The mirage of unconventional oil

OPEC also claims: “Technology continues to blur the distinction between conventional and non-conventional oil, of which there is also abundance, as well as with other fossil fuels. We expect the world’s URR [ultimately recoverable resources] to continue to increase in the future. Therefore, the real issue is not reserve availability, but timely deliverability.”

BP refers to URR as “an estimate of the total amount of oil that will ever be recovered and produced”, hence the Canadian tar sands are included.

The tar sands have become infamous due to how dirty the oil is and how energy-intensive it is to extract, along with the massive environmental devastation required in the process of extraction.

Scientific and environmental critics of tar sand extraction also argue that oil companies’ glowing forecasts of how much oil is there, along with how long it will take to extract are fantastic, in a literal sense of the term.

Hughes, whose expertise includes 32 years with the Geological Survey of Canada as both a scientist and research manager, calls the forecasts “exuberant”.

“They were at 1.5 million barrels per day (bpd) in 2010. Industry has tripled the forecasts in 25 years, which would put them at about 4.5mbpd. It’s taken 40 years to get the tar sands to 1.5 million bpd and the surface scar is incredible. I can’t imagine what that would look like if you tripled it.”

Hughes explained the government of Alberta reports 143bn barrels of oil, but “90 per cent of those are too deep to be surface minable. Huge energy inputs are required to get to that. So energy return on investment is going to go down a lot as the tar sands progress. I’ll believe they triple it when I see it … frankly I don’t think it’s possible. This is industry hype they are talking to their shareholders.”

The oil in the tar sands also requires time-consuming construction of more infrastructure to support its extraction and delivery, which, along with the aforementioned factors, lead Hughes to believe the tar sands “can’t be ramped up enough to offset declines of conventional oil”.

Read more from Al Jazeera: http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2012/02/201222051514575294.html

Photo by Akil Imran on Unsplash