- Antarctic krill are one of the most abundant species in the world in terms of biomass, but scientists and conservationists are concerned about the future of the species due to overfishing, climate change impacts and other human activities.

- Krill fishing has increased year over year as demand rises for the tiny crustaceans, which are used as feed additives for global aquaculture and processed for krill oil.

- Experts have called on the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), the group responsible for protecting krill, to update its rules to better protect krill; others are calling for a moratorium on krill fishing.

- Antarctic krill play a critical role in maintaining the health of our planet by storing carbon and providing food for numerous species.

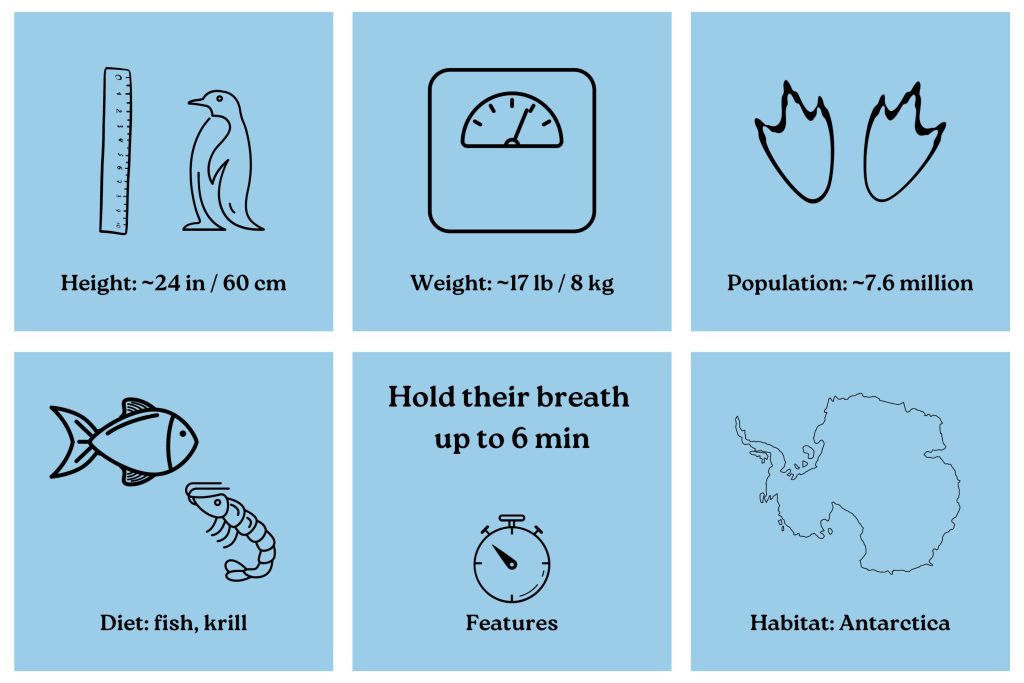

Antarctic krill — tiny, filter-feeding crustaceans that live in the Southern Ocean — have long existed in mind-boggling numbers. A 2009 study estimated that the species has a biomass of between 300 million and 500 million metric tons, which is more than any other multicellular wild animal in the world. Not only are these teensy animals great in number, but they’re known to lock away large quantities of carbon through their feeding and excrement cycles. One study estimates that krill remove 23 million metric tons of carbon each year — about the amount of carbon produced by 35 million combustion-engine cars — while another suggests that krill take away 39 million metric tons each year. Krill are also a main food source for many animals for which Antarctica is famous: whales, seals, fish, penguins, and a range of other seabirds.

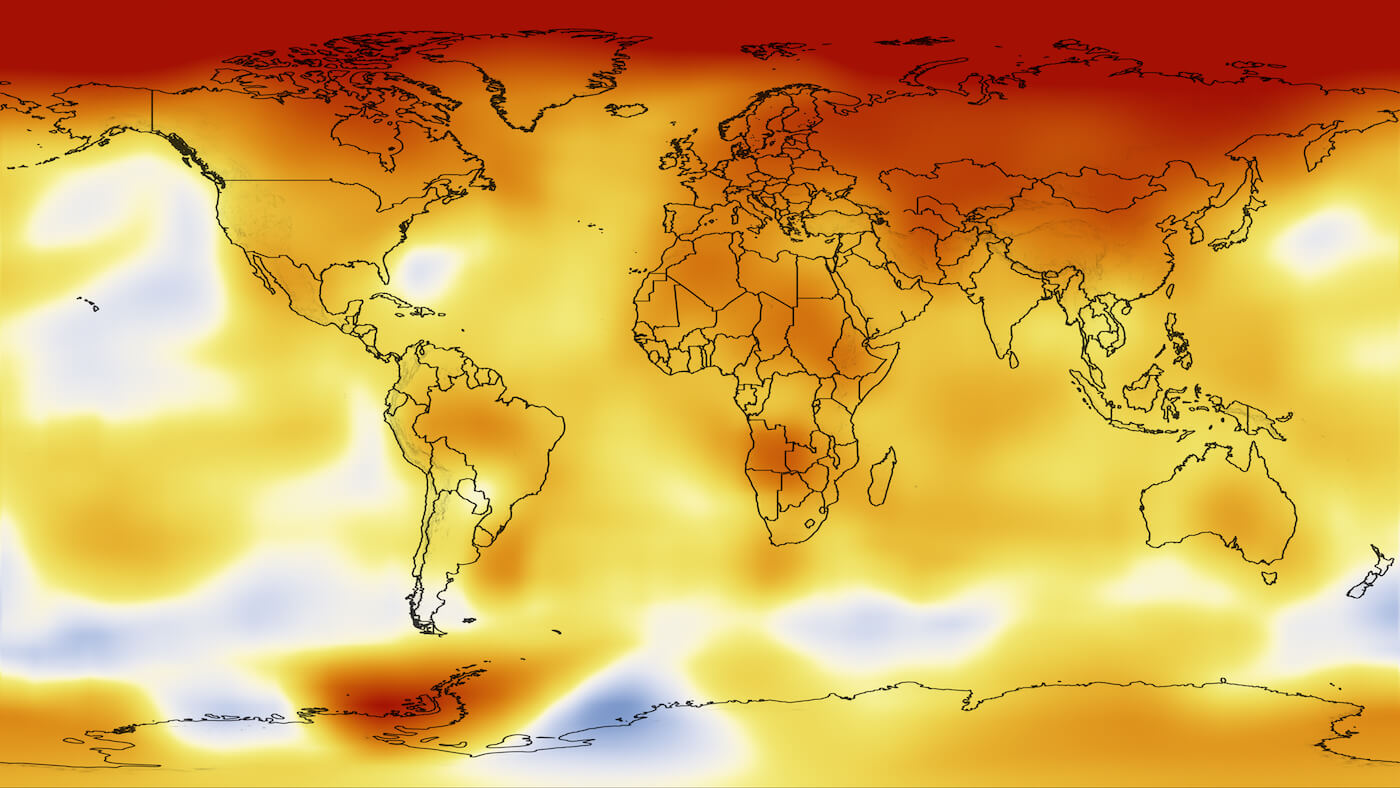

But Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) are not “limitless,” as they were once described in the 1960s; they’re a finite resource under an increasing amount of pressure due to overfishing, pollution, and climate change impacts like the loss of sea ice and ocean acidification. While krill are nowhere close to being threatened with extinction, the 2022 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change indicated that there’s a high likelihood that climate-induced stressors would present considerable risks for the global supply of krill.

“Warming that is occurring along the Antarctic Peninsula and Scotia Sea has caused the krill stocks in those areas to shrink and the center of that population has moved southwards,” Kim Bernard, a marine ecologist at Oregon State University, wrote to Mongabay via email while stationed in the Antarctic Peninsula. “This tells us already that krill numbers aren’t endless.”

Concerns are amassing around one place in particular: a krill hotspot and nursery at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula known as “Area 48,” which harbors about 60 million metric tons of krill. Not only has this area become a key foraging ground for many species that rely on krill, but it also attracts about a dozen industrial fishing vessels each year. The amount of krill they catch has been steadily increasing over the years. In 2007, vessels caught 104,728 metric tons in Area 48; in 2020, they caught 450,781 metric tons.

The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), the group responsible for protecting krill, has imposed rules to try and regulate krill fishing in the Southern Ocean, but many conservationists and scientists say the rules need to be updated to reflect the changing dynamics of the marine environment. That said, many experts argue that the Antarctic krill fishery can be sustainable if managed correctly.

Antarctic krill are under pressure due to overfishing, pollution, and climate change impacts like the loss of sea ice and ocean acidification. Image courtesy of Dan Costa.

Approaching krill ‘trigger level’

Fishing nations started casting their nets for Antarctic krill in the 1970s, believing these small crustaceans could provide a valuable source of animal protein that would alleviate world hunger. But in the 1980s, interest in krill fishing waned, partly because no one was sure how to remove the high levels of fluoride in their exoskeletons. It was also generally difficult to process krill into food fit for human consumption and to successfully sell these foods to consumers.

But krill fishing never really stopped. In fact, it’s been gaining momentum ever since krill was identified as a suitable animal feed. Now krill is mainly used as a feed additive in the global aquaculture industry, as well as to produce krill oil that goes into omega-3 dietary supplements.

In 1982, the CCAMLR was established to address concerns that the Antarctic krill fishery could have a substantial impact on the marine ecosystem of the Southern Ocean. In 2010, the CCAMLR established a rule limiting catches to 5.61 million metric tons across four subsections of Area 48 where krill fishing was concentrated. The rule also dictated that krill fishing in these areas must stop if the total combined catch reached a “trigger level” of 620,000 metric tons.

So far, total catches have not exceeded this boundary. But krill fishing nations, which currently include Norway, China, South Korea, Ukraine and Chile, are inching closer to it as they expand their operations.

“As long as catches were significantly below the trigger level, I think people felt like, ‘Oh, we don’t need to be too worried,’” Claire Christian, executive director of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC), told Mongabay. “They’re still not there yet, but as they’ve been getting closer, there’s been more pressure on CCAMLR scientists and policymakers to look at the fishery and develop a more comprehensive management system.”

Stuart Corney, an Antarctic krill expert at the University of Tasmania, said a primary concern is that most krill fishing is concentrated at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, where krill are known to spawn, creating “localized depletion.”

“If we overexploit the krill in that region, it can have significant implications for the population in a greater area of Antarctica … so it needs to be carefully managed efficiently,” Corney told Mongabay.

Another issue with the current catch limits is that they don’t consider the impacts of climate change, according to Bernard.

“This is particularly important at the Antarctic Peninsula where the fishing effort is greatest because the Antarctic Peninsula is one of the most rapidly warming regions on the planet,” Bernard said. “There is also evidence that areas along the Antarctic Peninsula such as the Gerlache Strait are important overwintering grounds for Antarctic krill, particularly for the juveniles and larvae that shelter in the bays and fjords along the Peninsula at that time of year. There is no seasonal closure on the krill fishery and because of delayed sea ice formation in the region around the Gerlache Strait the fishery can extend into winter. When that happens, the fishery could remove massive numbers from the next reproductive cohort of the population.”

Krill are known to lock away large amounts of carbon through their feeding and excrement cycles. Image courtesy of Aker.

Not only will global heating deplete the sea ice that krill depend upon, but research has suggested that warming waters will impact krill growth, possibly leading to a 40% decline in the mass of individual krill by the end of the century. Other research has argued that ocean acidification, another impact of climate change, will reduce krill development and hatchling rate and lead to an eventual collapse in 2300.

Progress and setbacks

In 2019, CCAMLR members agreed on a scientific work plan with the view of adopting new conservation measures based on it in 2021. This process was delayed due to COVID-19, but CCAMLR members are expected to reinvigorate these discussions at the next meeting in October, said Nicole Bransome, a marine ecologist at Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy.

“Hopefully, the scientists will have been able to put all of the science together … and come up with a new measure that spreads the catch out in space to reduce the impacts on predators,” Bransome told Mongabay. However, she said she’s concerned about a possible move to increase krill catch limits, which was discussed at last year’s meeting.

“Preliminary analysis suggests that the overall catch level could go up, but as of last year’s meeting, there were still a lot of uncertainties with that model and the parameters used in that model,” she said. “We would rather see that if the catch limits change, they’re based on a robust model and good science.”

While many experts say krill fishing can be sustainable if managed correctly, others call for stronger measures to protect krill.

Over the past decade, conservationists and scientists have been proposing the establishment of three new marine protected areas (MPAs) in East Antarctica, the Antarctic Peninsula and the Weddell Sea, ranging over 4 million square kilometers (1.5 million square miles) of the Southern Ocean, which would help protect krill with no-take zones.

“There is now strong scientific evidence that we need strict protection of at least 30% of the global ocean to effectively protect it,” said Christian of ASOC.

Yet the CCAMLR, which makes decisions based on consensus, has rejected the MPA proposal year after year.

Sophie Nodzenski, a senior campaigner at the Changing Markets Foundation, an NGO that works to expose irresponsible corporate practices and to foster sustainability, said the CCAMLR’s continued rejection of the MPAs had led her organization to call for a moratorium on krill fishing. (The Bob Brown Foundation, an Australian NGO that works to protect the natural world, has previously called for a similar ban on krill fishing to be put in place.)

“We are aware it’s a strong stand,” Nodzenski told Mongabay. “But there is a climate emergency, and there is a worry about how krill fishing is exacerbating the threats from climate change. So why don’t we just put a moratorium in place?”

In a report released Aug. 11 — for the first World Krill Day — the Changing Market Foundation details concerns for the planned expansion of the krill industry, which could push catch limits past the current trigger points. It also reveals how Norwegian company Aker Biomarine dominates the industry, supplying krill feed for farmed salmon operations around the world.

Consumers could alleviate pressure on krill “by pushing for a change in the way we are harvesting krill,” Nodzenski said. “If there’s less demand for products, eventually you could see a knock-on effect on the krill harvesting.”

Krill is fished so it can be used as a feed additive in the global aquaculture industry, as well as to produce krill oil that goes into omega-3 dietary supplements. Image courtesy of Pete Harmsen.

Is change coming?

The report also casts doubt on the CCAMLR’s ability to make timely decisions to protect krill.

“This is because CCAMLR’s decision-making process is based on consensus; as long as some members oppose changes to the status quo (in this regard, China and Russia), decisions cannot go ahead,” the authors write. “This means that, for the foreseeable future, it is difficult to envisage how management measures regarding krill can evolve and adapt to our rapidly changing climate.”

Yet other experts say the CCAMLR has the capacity to authorize effective changes.

“CCAMLR has a range of mechanisms it can use to further ecosystem protection,” Bransome of Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy said. “Lots of progress has been made … and we are looking to CCAMLR to achieve additional protections at the upcoming CCAMLR meeting.”

Corney from the University of Tasmania said he believes it’s important for fishing nations to continue working together through the CCAMLR to protect the Southern Ocean.

“If some nations started pulling out of CCAMLR … they’re not bound by the rules [and] they can do their thing,” Corney said. “We want all nations to remain in CCAMLR. We want them to sign up for the agreements that are reached. That means we have to accept the structure that is there.”

While opinions differ about how to manage the krill fishery, experts tend to agree on one thing: krill are too valuable to lose in this moment of climate crisis.

Antarctic krill are also a main food source for many animals, including whales, seals, fish, penguins, and a range of other seabirds. Image by Brett Wilks /Australian Antarctic Division.

“Even though Antarctic krill are seemingly far removed from our lives, some of that excess carbon dioxide we’ve pumped into the air is exported to the sea floor by krill, where it will remain for thousands of years,” Bernard said. “Without Antarctic krill, Earth would be even hotter than it already is.”

Citations:

Atkinson, A., Siegel, V., Pakhomov, E. A., Jessopp, M. J., & Loeb, V. (2009). A re-appraisal of the total biomass and annual production of Antarctic krill. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 56(5), 727-740. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2008.12.007

Tarling, G. A., & Thorpe, S. E. (2017). Oceanic swarms of Antarctic krill perform satiation sinking. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1869), 20172015. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.2015

Belcher, A., Henson, S. A., Manno, C., Hill, S. L., Atkinson, A., Thorpe, S. E., … Tarling, G. A. (2019). Krill faecal pellets drive hidden pulses of particulate organic carbon in the marginal ice zone. Nature Communications, 10(1). doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08847-1

Spiller, J. (2016). Frontiers for the American century: Outer space, Antarctica, and cold war nationalism. Springer.

Pörtner, H., Roberts, D. C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E. S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., … Rama, B. (Eds.) (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Retrieved from IPCC website: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

Klein, E. S., Hill, S. L., Hinke, J. T., Phillips, T., & Watters, G. M. (2018). Impacts of rising sea temperature on krill increase risks for predators in the Scotia Sea. PLOS ONE, 13(1), e0191011. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191011

Kawaguchi, S., Ishida, A., King, R., Raymond, B., Waller, N., Constable, A., … Ishimatsu, A. (2013). Risk maps for Antarctic krill under projected Southern Ocean acidification. Nature Climate Change, 3(9), 843-847. doi:10.1038/nclimate1937

Changing Markets Foundation. (2022). Krill, Baby, Krill: The corporations profiting from plundering Antarctica. Retrieved from https://changingmarkets.org/portfolio/fishing-the-feed/

Banner image caption: Antarctic krill. Image courtesy of Dan Costa.

Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a staff writer for Mongabay. Follow her on Twitter @ECAlberts.

![Adélie Penguins [Fight for Who We Love]](https://dgrnewsservice.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2023/04/Adelie-penguins-on-ice-980x695-1-980x675.jpg)