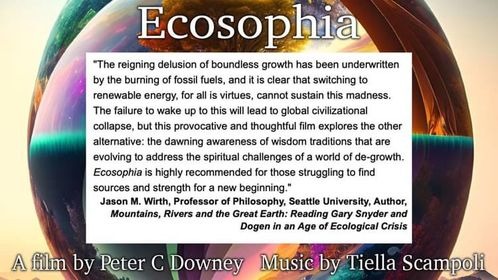

Ecosophia by Peter Charles Downey – Film Review

The film Ecosophia is a tour through many of the issues facing humanity: our addiction to growth, energy, and materials, and our devastating use of “surplus energy” to extract and consume—and thus destroy—the very system that sustains us. The narrative of the film is told through a series of short interviews, interspersed with reflections by the filmmaker, Peter Charles Downey.

Each interviewee brings a slightly different perspective on the predicament we are in: a completely unsustainable industrial civilization that is causing ongoing collapse of the living Earth; a global civilization that will soon collapse under its own weight.

The film begins by describing the fundamental problem: infinite growth on a finite planet. Tim Garrett describes what exponential growth means—the doubling over the next 30 years of the total energy and raw materials used by humanity in the past 10,000 years. Sid Smith explains that, no, renewables will not save us. Ian Lowe reminds us that we are right on track to match the predictions of the Limits To Growth—that is, collapse somewhere between 2030-2050 of civilization as we know it now. Climate change is highlighted but correctly understood and described as just one symptom of the overarching problem we’ve created for ourselves.

A little history: as soon as we learned how to store surplus, we were in trouble. This “storing of surplus” is often associated with the beginning of agriculture, but as John Gowdy describes, it actually happened before agriculture. Just one example: Pacific Northwest Native Americans learned how to smoke salmon and store it over the winter. This led to hierarchy and inequality, the inevitable outcomes of stored surplus, as the tribe who could best store salmon would gain priority over the best salmon runs, just like kings and emperors created hierarchy and inequality by storing surplus grain, thus creating slavery and the need for soldiers to protect the grain. The ability to store surplus is what allowed us to grow far beyond the carrying capacity of Earth to sustain us.

We are torn between Stone Age instincts and space age technology and we don’t know how to cope. As Bill Rees describes, we now have the capacity via fossil fuels and technology to grow exponentially, breaking the bounds of the constraints most species face—disease, resource shortages, etc.— which kept our population in control until about 10,000 years ago.

We learn about one third of the way into the film that Ecosophia means the passing on of knowledge over many generations about the specifics of place; of how to live well in a place, deeply understanding the climate, soil, and natural communities of that place. This localized knowledge is what allowed us to live sustainably on the land as a species for thousands of years before we went astray.

From here, the film moves from describing the problem into describing how we got here: a fundamental disconnection with ourselves, with the natural world, with that localized knowledge and respect for place. The interviews cover this disconnection well; Stuart Hill, a permaculturist, describes how our theistic religions come with spiritual beliefs that are limitless, but that nature has limits, and this spiritual disconnection from the reality of the natural world is a crisis for us as a species because we are utterly dependent on that natural world.

My favorite part of the film is perhaps the interview with Stephen Jenkinson, who is known for his work on Orphan Wisdom. “Exercising dominion is a surrogate for belonging,” he says, which is such a wonderfully concise and precise way to describe what we are doing to the Earth. We are orphans from the natural world, he says, not in the sense that our parents are dead, but rather that we cannot get to our parents (the natural world), and so, we don’t know how to belong. He says, “This is not a recipe for shame or class action guilt, despite the regime for social justice.” I strongly resonated with this, because of the extreme shame and guilt that are so pervasive in the critical social justice movement that is currently sweeping the Western world, and which seems so wrong-headed.

We orphans—and all of us who watch the film and read this review are orphans—will have to do the work to reconnect because we no longer inherit belonging through our ancestors, the ones who knew how to live well in a place. We are orphans because we can no longer access that generational knowledge in a modern culture that has all but destroyed it; we must do the work to recreate it ourselves. That is a multi-generational task. Are we up to it? As Stephen asks in the film, “How bad does it have to get before we question the utility of persisting?”

It’s clear in the film that the filmmaker recognizes the narcissism of focusing on self-improvement over taking responsibility for what we have done, what we are doing. Interviewee Alnoor Ladha describes this as “retreat consciousness.” He identifies that our loss of belonging makes us feel victimized, because we are “brought into a world that doesn’t belong to us” and our coping mechanism is to try to get as much as we can “on the sinking ship, to have a first-class cabin on the Titanic.”

Yet the message we are left with at the end of the film is profoundly disempowering. The last interviewee, John Seed, who is in the deep ecology movement, concludes that if we—humanity—are destroying the Earth, then we are the Earth destroying herself, because there is no separation between us and the Earth.

On the one hand, yes, that is true. We humans are nature. And on the other hand, to describe the cruelty and psychopathy of what humans are doing to the Earth as “the Earth destroying herself” is to utterly misunderstand the Earth and at once assign too much, and too little agency to the natural world.

The film has laid out the problem of the physical and spiritual crises we face, encouraged us to do the first steps—the work on ourselves to understand the problem and cultivate the desire to do something about it, and to relearn and recreate the wisdom for how to live well in a place—and then completely diffuses any energy and passion this might have inspired in the viewer by giving us an out.

At the very end of the film, the filmmaker moves into full-on human supremacy mode, saying that we humans are perhaps “special” and “unique,” because we haven’t found evidence of “any other intelligent life-form in the universe.” He says that what makes us special is that we evolved a passion to learn about ourselves, and that if we are indeed unique in the universe, that we might want to “keep this going.”

What’s shocking about this conclusion—that we are unique and rare and special, that we are the only “intelligent life-form in the universe”—is that it is so obviously untrue. Throughout the film, I enjoyed the many wonderful clips of animals and natural communities. Why is the filmmaker not able to see that this is the intelligence he thinks is missing out there in the Universe? It’s right here with us.

The Earth may indeed be unique in all of the universe in her capacity to support life, but we humans are not alone: we are surrounded by intelligence and love in the ecosystems and many species with whom we share this amazing planet. To listen to all of these interviews, to be able to appreciate the many life-forms on Earth, and yet conclude that humanity’s utter destruction of what might be the only planet capable of sustaining life in the entire universe is “the Earth destroying herself” and that this is part of nature is disappointing, to say the least.

In conclusion, I recommend the film, but caution viewers: there is another, better ending to envision. Yes, we must understand the problem. Yes, we must do the work on ourselves. Yes, we must listen to people who still understand ecosophia: that living well in a place with humility and respect for the natural world is the only way for us to live sustainably on the Earth.

And then we can take action. We can fight back against the forces that push us further into disconnection from reality each and every day. This is what the Earth herself wants us to do, if we’d only listen. Fight back!

Thank you to Peter Charles Downey for access to the preview of the film Ecosophia.

Photo by Ray Hennessy on Unsplash

I’ve mentioned this before – that the term “climate change” should be changed to “pollution” because then we will easily see what the cause of the problems are. We pollute. But why do we humans pollute? The answer is because of the money system. The money system provides “profits” and this is the holy grail of our modern lives. The money system is the fountainhead for pollution or climate change if you like. We need to strike at the root. It disappoints me that some scientists still don’t seem to have heard that fossil fuels are plentiful. Decades ago we were told we would run out by the 2000’s but that didn’t happen. We probably use more fossil fuels today than ever before with all our electronics. Why is this major piece of information or theory, never admitted by “climate change scientists” hmm? Perhaps there’s money to be made from the killing of our earth too?

Oh and I nearly forgot – how about they stop poisoning us in the skies, water and soil? Why are these assaults never mentioned in “climate change” discourse They are “geoengineering” the weather, what are they spraying in the skies? Where does it go? What affect does it have on the water, soil, animals, humans? Why are no scientists asking this or even acknowledging it? Do you think that planes make this mess in the sky in the 21st century when they didn’t last century? Do you think aviation technology has become more polluting over the decades? Why is nobody talking about this?

Thank you for this review, Elisabeth. I had not heard of this film before. I noticed that all of the interviewees from the film that you named have names that sound both male and European. Are those the only types of voices that speak in this film? Even if such voices make up 70 or 80 percent of the film’s speakers, that would make it highly suspect to me of likely being a misleading, gap-filled presentation, and therefore not worth watching. We need more feminine and Indigenous voices being heard on this most important of issues. Their voices are much more likely to lead us back to connection with our original Earthways than members of the dominant types of humans who were most responsible for bring us colonialism, the industrial revolution and Earth overshoot. I realize that humans began to fall out of harmonious relations with Earth systems long before there were civilizations in a place called “Europe,” but I just hope that other voices were included, like maybe Robin Wall Kimmerer, Riane Eisler, or Vandana Shiva, or you!

Also, on the notion that storing surplus food was some sort of major wrong turn by our species, or the beginning of all our trouble, I just have to say no, not really. Whoever said that probably has no idea what it takes to survive living in nature’s ways in a place that has actual freezing winters. The reason that the indigenous peoples of such places smoke fish and meat and dry mashed berries into the original “fruit leather,” and do many other things to have a stash of food at hand in the long months when nothing grows and many of our non-human relations hibernate, is because if we didn’t do that we would starve to death. Not only do the humans do that, but so do the squirrels, the chipmunks and many rodents and species of birds. Maybe it all depends on how you define “surplus,” but our ancestors who lived in the old ways had a good understanding of what was excessive, what was necessary, and what was good enough, as well as the limits and laws of their particular homelands, taking into account the needs of all species with whom we share place.

Totally disagree with you.

First, you exhibit identity politics, which means you have no valid counterargument. It’s not where you’re from, it’s where you’re at. Anyone who tries to convince you otherwise is full of it. My ancestry is European, and I’m more Earth-oriented and more of an advocate for the natural world than a Native friend who was raised in a city by white foster parents. Your claim about this is ludicrous. I’ll put my environmental credentials up against anyone, including Natives. That said, my American Indian Movement and International Indian Treaty Council friends and I never disagreed on environmental issues when I was an Earth First! campaigner, so I suspect that you’re not a traditional Native.

Second, as to your claim about how hard it is for humans to live as hunter-gatherers outside the tropics, that’s correct. However, your conclusion is wrong: it just means that humans should stay in the tropics where we belong. I have no opinion regarding the surplus food issue as it’s presented here; as you say, some non-humans store food for winter too, so I don’t see that as a problem. The problem with humans living outside the tropics is that they have to do unnatural and harmful things to live there, like creating artificial sources of heat and much more extensive shelters. We are tropical animals, and should get back to living there.

Fully agree about John Seed, very disappointing comments. I met John at an Earth First! rendezvous about 40 years ago, and he was totally cool then. Don’t know what idiocy led him to this conclusion, but it’s utter nonsense. Humans have separated themselves from nature and the natural world, so it’s irrelevant that we came from them. Starting at least from the use of agriculture, and possibly going back to when we started leaving Africa and caused extinctions wherever we went, humans fit the medical definition of being a cancerous tumor on the Earth. The only exceptions are aesthetic monks and hunter-gatherers, who together comprise only a tiny fraction of 1% of humans. While these people should be our guiding lights and they are not part of the cancer, they are so few and far between that they’re not worth mentioning except as examples of how humans should live and act.

As Elisabeth Robson wrote, John Seed’s comment is nothing but a BS copout, a lame excuse for the destruction of the Earth and massive killing of native life that humans are doing. This is not the Earth killing itself, humans are not a part of nature and haven’t been for a very long time, and we need to reverse all this, starting with admitting what we’re doing and taking responsibility for it. Anything less is totally unacceptable.