by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Sep 29, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

by Jo Woodman and Alicia Kroemer / Intercontinental Cry

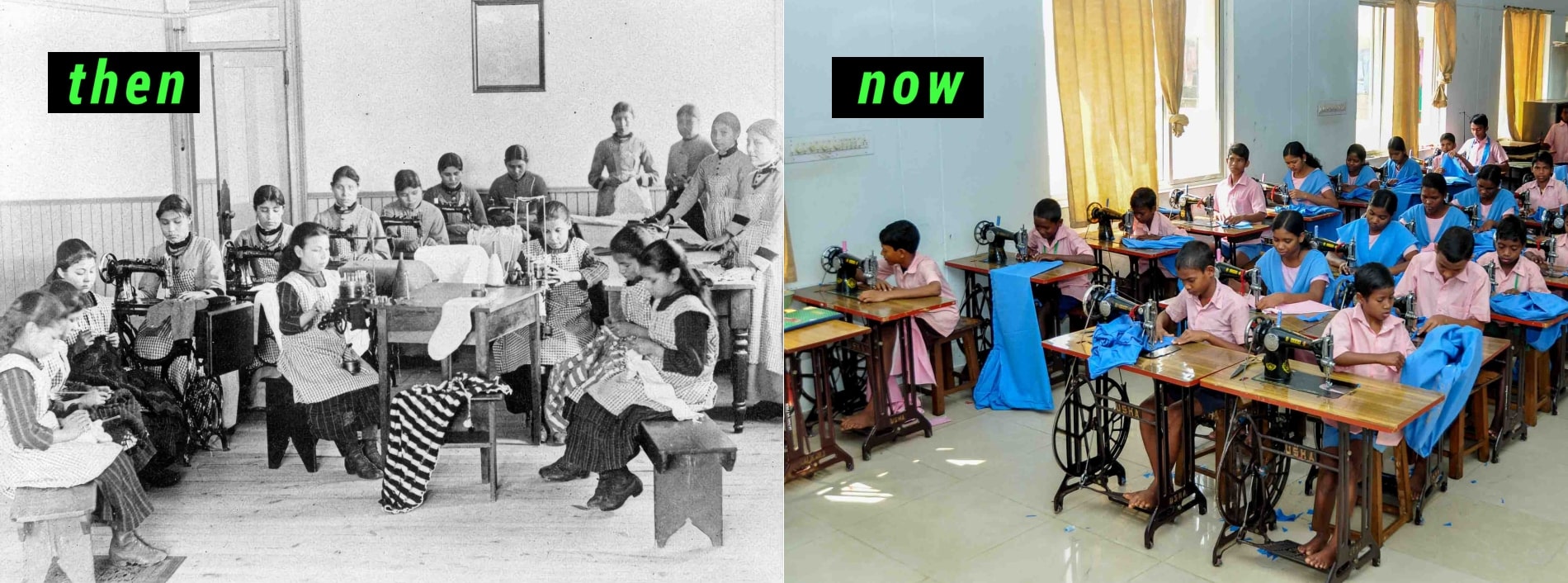

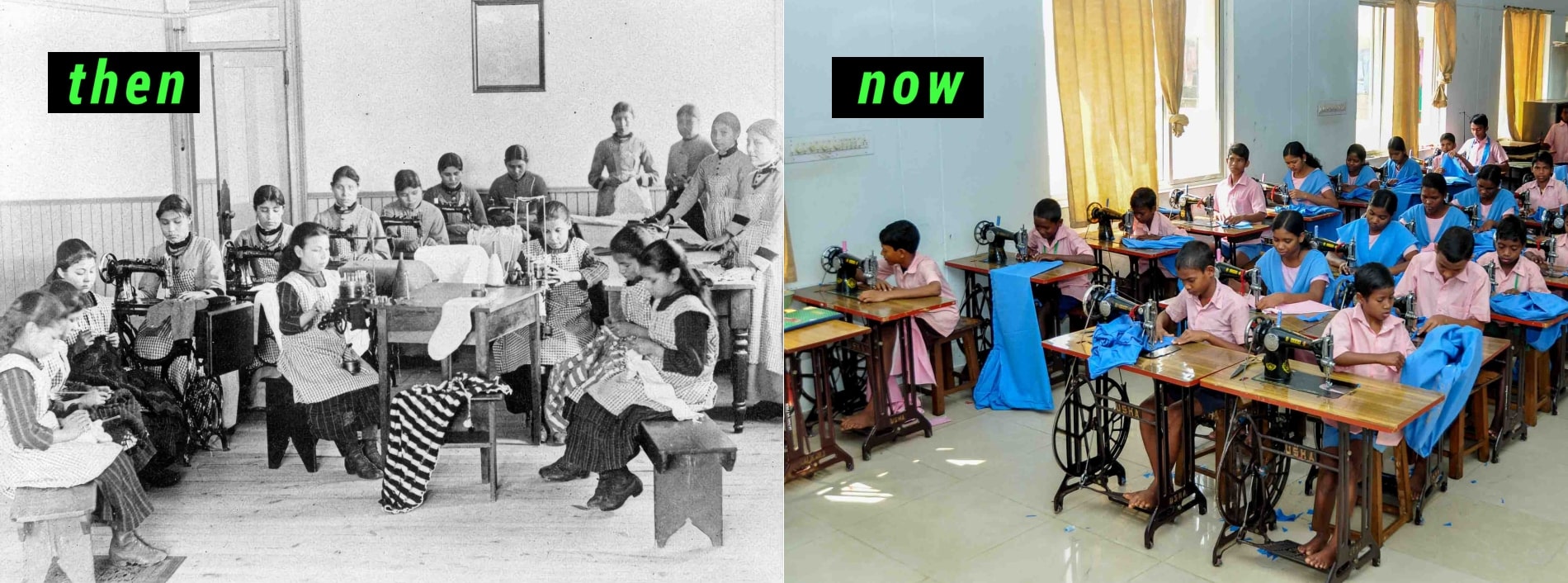

On September 30, communities across Canada will be commemorating ‘Orange Shirt Day’, an annual event that is helping Canadians remember the thousands of Indigenous children who died in Residential Schools, and to reflect on the intergenerational trauma that was caused by the Residential school system. Similar school systems were also run in the US, New Zealand and Australia with terrible consequences for Indigenous children and communities.

Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation elder Phyllis Jack Webstad founded Orange Shirt Day in 2013, after she shared her childhood experience at the St. Joseph’s Mission residential school in William’s lake, British Columbia.

Residential school staff stripped her of her favourite orange shirt the day she was taken from her family. As Residential school survivor Vivian Timmins said today, “The orange day shirt is a commonality for all Native Residential School Survivors because we had our personal items taken away which was a tactic to erase our personal identity. Maybe it was a piece of clothing, but it represented our memory that connected us to families. Today is a time to honour the children and youth that didn’t make it home. It’s a time to remember Canada’s dark history, to educate and ensure such history is never repeated.”

Alarmingly, that history is being repeated in many parts of the world. According to Survival International, there are nearly one million tribal and Indigenous children across Asia, Africa, and South America who are currently attending institutions that bear a striking resemblance to Canada’s residential schools.

Indigenous artist RG Miller’s haunting autobiographical painting recalls the horrific abuse he experienced at residential school. Photo Courtesy RG Miller

A horrifying legacy lives on

The horrifying legacy of residential schools is being repeated, on a massive scale, because the attitudes and intentions underlying Canada’s residential school system live on.

Tribal and Indigenous children around the world are being coerced from their families and sent to schools that strip them of their identity and often impose upon them alien names, religions, and languages.

Extractive industries and fundamentalist religious organizations are frequently pulling the strings behind these institutions.

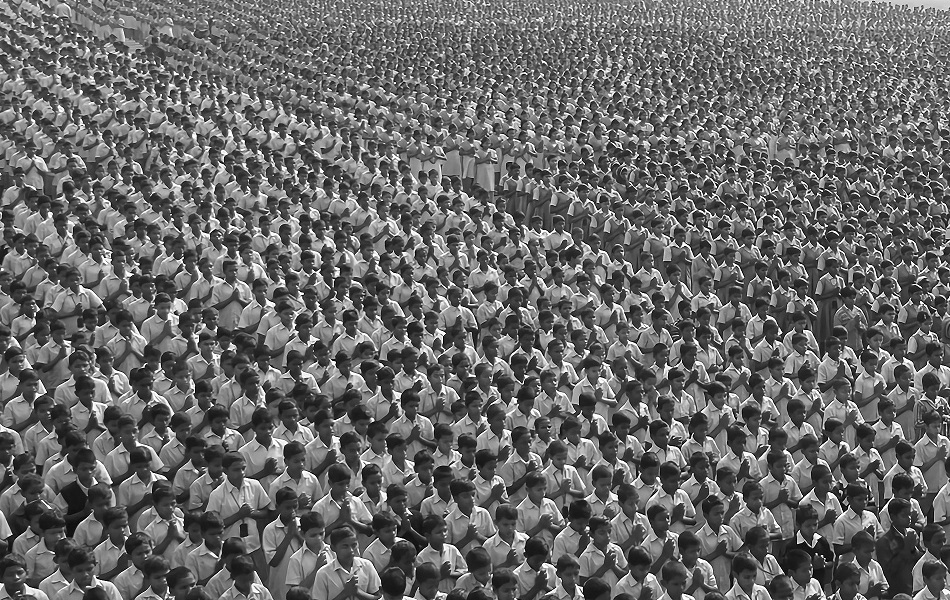

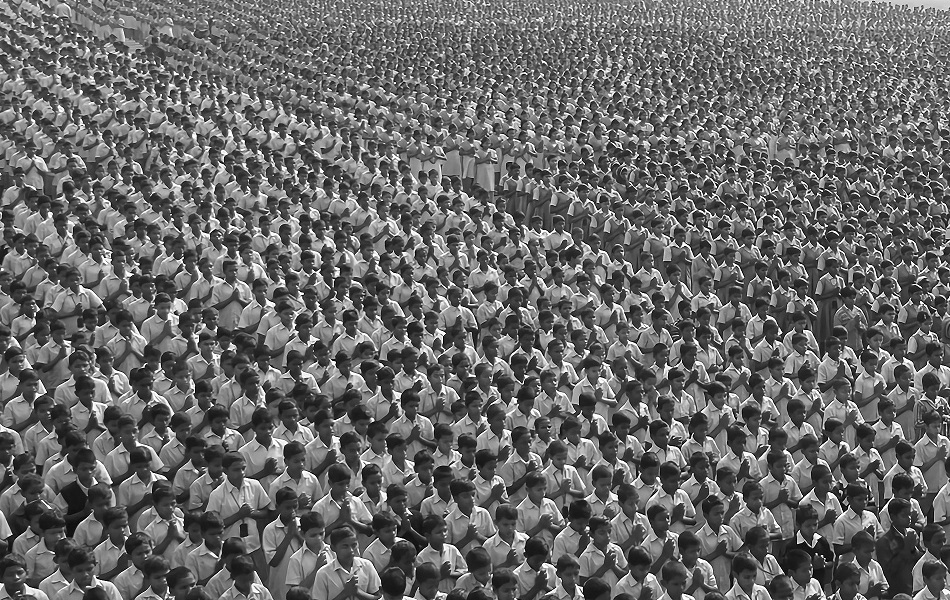

One residential mega-school in India—which boasts it is “home” to 27,000 Indigenous children—states publicly that it aims to turn “primitive” tribal children from “liabilities into assets, tax consumers into tax payers.”

Its partners include the very mining companies that are trying to wrest control of the lands these children truly call home.

Parents have described the school as a “chicken farm” where children feel like “prisoners.”

An expert on Adivasi education told us, “Their whole minds have been brainwashed by a kind of education that says, ‘Mining is good’, ‘Consumerism is good’, ‘Your culture is bad.’ Tribal residential schools are institutions which are erasing the autobiography of each child to replace it with what fits the ‘mainstream’. Isn’t it a crime in the name of schooling?”

Without urgent change, many distinct peoples could be wiped out in just a few generations, because the the youth in these schools are taught to see their families and traditions as ‘primitive’, ‘backward’ and inferior to ‘mainstream’ society so that they turn their backs on their languages, religions and lands.

Survivors of Canada’s residential schools are beginning to speak out against these culture-destroying institutions.

“What’s happening right now at these residential schools in India and beyond is very similar to what happened with the residential schools in Canada”, says Roberta Hill

Roberta Hill is a survivor of the Mohawk Institute in Brantford, Canada, where she was abused by the pastor and school staff in the 1950s and 60s. She sees the strong parallels between her experience and that of Indigenous children in these modern culture destroying schools: “What’s happening right now at these residential schools in India and beyond is very similar to what happened with the residential schools in Canada – this separation of Indigenous children from their family, language, and culture is a very destructive force. My experience at residential school was traumatizing. I was taken from my family at the age of six and put in the school where I experienced a lot of abuse and isolation. If this is happening again now, then there needs to be international attention. It needs to stop or else they are going to go through the same thing that we went through. It will cause irreparable damage – not only to the Indigenous children attending, but to the future generations of that community.”

RG Miller, a prominent Indigenous artist from Canada states: “My horrific experience at Native residential school destroyed my connection with community, family, and my culture. The abuses I suffered there completely broke any sense of trust or intimacy with anyone or anything including God, spouses, and children for the rest of my life.”

Over the past two decades, thousands of residential school survivors have shared their stories of abuse; but there are thousands of other children who will never be able to tell their own stories because they passed away while they were in a residential school. Other children, like Chanie Wenjack, died while trying to escape. The young Ojibwe boy ran away from his residential school in Ontario, trying desperately to reach home, 600 km away. He died of hunger and exposure at the age of 12 in 1966.

Half a century later—and 12,000km away—Norieen Yaakob, her brother Haikal and five of their friends, fled their residential school in Malaysia. The children, who belong to the Temiar—one of the Orang Asli tribes of central Malaysia—ran away to avoid a beating from their teacher. 47 days later, Norieen and one other little girl were found, starving but alive. The other five children died, including Haikal and seven-year-old Juvina.

Juvina’s father, David, told us, “The police said, “Why are you bothering us with this problem?” We felt hopeless. It was only on the sixth day that the authorities began their search and rescue mission for the children. But they told us parents to stay behind. They said if we went in it would just be to secretly give food to the missing children that we were supposedly hiding. They accused us of faking the whole incident to gain attention and force the government to help us more. That was what they thought of us… [Finally] they found a child’s skull and we could not identify immediately whose child it was. We had to wait for the post-mortem. I could not recognize my own child.” The families are currently taking the authorities to court in a case that the world should be watching.

Norieen Yaakob of the Temiar tribe of Malaysia barely survived running away from her residential school. She was found 47 days after fleeing her school; five other children died.

The terrible truth is that Indigenous children are dying in these schools. In tribal residential schools in Maharashtra state in India, over one thousand deaths have been recorded since 2000, including many suicides. With echoes of the traumas experienced in Canada, many parents never learn that their children are ill until it is too late, and they often never know the cause of death.

There are also a frightening number of cases of physical and sexual abuse, very few of which reach the justice system. Government schools across Asia and Africa are often staffed by teachers who have no connection to, or respect for, the communities they serve. Teacher absences are common, and abuse goes unseen and unreported. The potential for devastating damage is extremely high.

Survival International will soon launch a campaign to expose and oppose these culture destroying schools and to demand greater Indigenous control of education, before it is too late for these children, their communities, and their futures.

There is certainly a need for it. These schools endanger lives and strip away identities, but they also deny children the right to choose a tribal future.

The ability of Indigenous Peoples to live well and sustainably on their lands depends on their intricate knowledge, which takes generations to develop and a lifetime to master. To survive and thrive in the Kalahari Desert or to herd reindeer across the Arctic tundra cannot be learnt in residential schools, or on occasional school vacations.

What’s more, in this current age of severe environmental degradation, climate change and mass extinctions, Indigenous Peoples play a crucial role in preserving the world’s ecosystems. They are the best guardians of their lands and they should be respected and listened to if we have any hope of survival for future generations.

Rather than erasing their knowledge, skills, languages, and wisdom through culture-destroying residential schools, we must allow them to be the authors of their own destinies as stewards and protectors of their own lands.

Tribal children in Indonesia learning on their land, in their language. Photo: Sokola Rimba

Dr. Jo Woodman is running Survival International’s upcoming Indigenous Education campaign. She has spent two decades researching and campaigning on Indigenous rights issues, focused on the impacts of forced ‘development’, conservation and schooling on tribal communities.

Alicia Kroemer holds a PhD in political science from the university of Vienna on collective memory and residential schools in Canada, with publications, films, and lectures on the topic. She serves on the board of Indigenous rights NGO Incomindios in Zurich, where she is a human rights educator and UN representative. She also works as a research consultant for Minority Rights Group and Survival International in London, UK. She is interested in allyship, advocating and promoting human rights, with a special focus on Indigenous rights globally.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Aug 15, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: The Guardians of the Amazon recently destroyed a logging truck they discovered in their territory. © Guardians of the Amazon

by Survival International

Warning: some people may find the details and image below disturbing

A leader of an Amazon tribe acclaimed for its environmental defenders has been killed, the latest in a series of deaths among the tribe.

The body of Jorginho Guajajara was found near a river in the Brazilian state of Maranhão. He was a leader of the Guajajara people, acclaimed internationally for their work as the ‘Guardians of the Amazon’ in the most threatened region in the entire Amazon.

It is not yet clear who killed him, but a powerful logging mafia has repeatedly targeted the tribe for its work protecting both its rainforest home, and the uncontacted members of a neighboring tribe, the Awá, who also live there, and face catastrophe unless their land is protected.

Jorginho Guajajara’s body was found near a river in the eastern Brazilian Amazon.

Confronted with official inaction, the tribe formed an environmental protection team named the Guardians of the Amazon to expel the loggers. Some estimates suggest up to 80 members of the tribe have been killed since 2000.

The murder of Jorginho Guajajara is further indication of the increasing volatility in this area. In May this year, a team from Ibama (Brazil’s environmental protection agency) and environmental military police were dispatched to the Guajajara’s Arariboia reserve, a rare move from the authorities.The Guajajara say: “Our uncontacted Awá relatives cannot survive if their forest is destroyed. As long as we live, we will fight for the uncontacted Indians, for all of us, and for nature.”

Survival International has protested to the Brazilian authorities about the wave of violence against the Guajajara, which has gone almost entirely unpunished.

Survival International Director Stephen Corry said today: “The Guardians of the Amazon face an urgent humanitarian crisis, and are fighting for their very survival. This small tribe of Amazon Indians are confronting an aggressive, powerful and armed logging mafia with close ties to local and national politicians. And they’re paying with their lives for standing up to them. They urgently need public support to make sure they survive.”

The Guardians of the Amazon

– The “Guardians of the Amazon” are men from the Guajajara tribe in Brazil’s Maranhão state who have taken it upon themselves to protect what remains of this eastern edge of the Amazon rainforest.

– They want to save the land for the hundreds of Guajajara families who call it home, and their far less numerous neighbors: the uncontacted Awá Indians.

– The Guardians say of their work: “We patrol, we find the loggers, we destroy their equipment and we send them away. We’ve stopped many loggers. It’s working.”

– The Guardians recently released video and images of a rare encounter with the uncontacted Awá living in Arariboia. Watch the footage here

– You can see videos of several of the Guardians talking about their work on Survival’s Tribal Voice site.

Arariboia

– The Arariboia indigenous territory comprises a unique biome in the transition area between the savannah and the Amazon rainforest.

– There are species here not found elsewhere in the Amazon.

– The land inside the indigenous territory is under threat from illegal loggers

– Brutal cuts in government funding to its indigenous affairs department FUNAI and tribal land protection mean the dangers are now even greater, as the area is not properly monitored or defended by the authorities.

– A powerful and violent logging mafia operates in the region, supported by some local politicians.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 20, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: Dakota Access Pipeline Resistance Camp, October 12, 2016. Photo: Irina Groushevaia/flickr.

by Rebecca Pilar Buckwalter Poza / Intercontinental Cry

Standing Rock protesters faced below-freezing conditions, water cannons, sponge rounds, bean bag rounds, stinger rounds, teargas grenades, pepper spray, Mace, Tasers, and even a sound weapon. Officers carried weapons openly and threatened protesters constantly, by many accounts. Hundreds of protesters were injured, and more than two dozen were hospitalized.

As of November 2016, 76 local, county, and state agencies had deployed officers to Standing Rock. Between August 2016 and February 2017, authorities made 761 arrests. One protester was arrested and slammed to the ground during a prayer ceremony; another described being put in “actual dog kennels” with “photos of the types of dogs on the walls and piss stains on the floor” in lieu of jail. She wasn’t told she was under arrest; she wasn’t read her rights. Once detained, protesters were strip searched and denied medical care. Belongings and money were confiscated, the latter never returned.

Law enforcement officers razed the camp in February 2017. The protest may have ended, but aggression against protesters did not. Law enforcement and prosecutors’ efforts to charge protesters with as serious a crime as possible have become battles to convict them and obtain the maximum sentence possible.

During a Oct. 27, 2016, roadblock protest of the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock, several fires were set. By whom, no one knew. Prosecutors charged Little Feather of the Chumash Nation, also known as Michael Giron, and Rattler of the Oglala Lakota, Michael Markus, with “use of fire to commit a felony” as well as civil disorder, anyway. The charging documents cite knowledge of “several fires … set by unidentified protesters.”

Police tactics on Oct. 27, by the way, included the use of pepper spray and armored vehicles. Law enforcement and prosecutors only became more aggressive after President Trump assumed office, at his direction.

Both Little Feather and Rattler opted to plead guilty, not because there was adequate evidence against them but because the mandatory minimum sentence would be 10 years if they were convicted at trial. That was a risk not worth taking: The Guardian has reported that surveys found 84 to 94 percent of the jury pool has prejudged Standing Rock protesters. Little Feather was sentenced to three years in prison. Rattler is expected to receive the same or a similar sentence.

A third protester, Red Fawn Fallis, pleaded guilty to charges of civil disorder and illegal possession of a firearm by a convicted felon. She was accused of firing a gun during the protest, though she said she doesn’t remember doing so. The gun in question was owned by an informant who allegedly seduced Fallis. Despite these obvious flaws, she and her attorneys opted not to risk trial, citing both anti-protester sentiment and lacking disclosure by the prosecution. She received a 57-month sentence.

The ongoing experiences of Standing Rock protesters are all the more horrifying in contrast with the recent pardon of Dwight and Steven Hammond. Trump pardoned the pair, who’ve long “clashed” with the federal government, at the behest of a “tycoon” friend of Vice President Mike Pence. Both had been convicted of setting fires on federal land for a 2001 fire, while only Steven was convicted of a 2006 fire. When the mandatory minimum sentence for the pair—who originally benefited from pro-rancher bias—was imposed on appeal, it sparked an armed standoff led by another famous family of anti-government extremists, the Bundys.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jul 14, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: The Shipibo-Konibo people rely on forests for hunting, fishing and natural resources. Photo by Juan Carlos Huayllapuma/CIFOR

by World Resources Institute via Intercontinental Cry

The Santa Clara de Uchunya community has lived in a remote section of the Peruvian Amazon for generations. Like many indigenous groups, this community of the Shipibo-Konibo people have traditionally managed and relied on forests for hunting, fishing and natural resources.

But in 2014, someone started cutting down large sections of the community’s ancestral forests.

Without community members’ knowledge or consent, the regional government had given away 200 parcels of land, which were then bought by palm oil company Plantaciones de Pucallpa, part of a foreign group of companies with known environmental and legal troubles.

Community members turned to indigenous organization FECONAU for help, but there was a problem: Santa Clara de Uchunya only had formal legal title to a small sliver of their ancestral lands — about 218 hectares (539 acres) out of some 8,000 hectares (19,800 acres) they occupied.

So in 2015, the community requested an extension of their title to their full ancestral lands. The Regional Government responded bymaking vague promises and implying that the existence of competing claims to the land made any action impossible. Faced with administrative inaction, the community filed a lawsuit to compel the government to recognize their constitutional rights to their ancestral land.

The lawsuit remains stuck in the courts, and the community has only been able to obtain a government commitment to a small 750-hectare extension. When officials and community members tried to complete the necessary mapping for this extension, a large crowd, presumably affiliated with the palm oil operations, blocked their path.

Community members continue to advocate, but they’ve been met with intensifying violence. Unknown armed men came to their homes, making threats like “we are ready to kill.” They beat a community member who refused to leave his land and opened fire on a community delegation trying to gather evidence of deforestation.

Meanwhile, palm oil operations continue, despite multiple injunctions ordering a halt to the company’s operations for failing to obtain proper permits and for illegally deforesting at least 5,300 hectares (13,000 acres).

“We never thought that we would have such problems with transnational companies,” said Carlos Hoyos Soria, leader of the Santa Clara de Uchunya community. “We live from hunting, fishing — from the resources that the forest has to offer. Indigenous people without land are nothing.”

Santa Clara de Uchunya’s Struggle for Land Rights Is a Global One

The story of Santa Clara de Uchunya is all too familiar. New WRI research finds that across 15 countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia, rural communities and Indigenous Peoples face steep challenges to formalizing their land rights. While they wait decades for legal titles that may never come, companies acquire land or begin operations in as little as 30 days (experience the difference in processes through our interactive infographic). The resulting conflicts over the contested land can last years, displacing communities and creating significant legal and economic risks for companies.

Indigenous Peoples and rural communities occupy more than half of the world’s land, but they legally own just 10 percent of land globally. Obtaining formal land rights is one of many tools they use to try and protect their land, but our research finds clear inequities in these procedures:

Communities face an uphill battle when trying to obtain formal rights to their land. Many communities do not realize that their customary forms of land ownership lack legal protection; those that do often lack the legal knowledge and resources to begin the process of applying for formal rights. While laws differ by country, land formalization procedures often involve difficult steps like writing technical reports or legal documents. In practice, most communities need help from an outside non-profit organization. Furthermore, as seen with Santa Clara de Uchunya, when conflicts or overlapping land rights and concessions exist, communities may be unable to title their lands at all. We found this to be a key challenge not only in Peru, but also in countries like Indonesia, Tanzania, Guyana and Mozambique.

Even when communities do obtain titles, these documents exclude ancestral lands and natural resources. Santa Clara de Uchunya’s original title was a tiny sliver of their total territory. Many communities similarly have ancestral lands excluded from their titles, with government authorities imposing arbitrary caps on the size of land they grant to communities. Elsewhere, certain types of land cannot be included in titles: in Peru, communities must complete a separate procedure if the government classifies the land as “forestland.” Even then, they can only get a contract to use their land (a cesión en uso), not ownership rights. In practice, only a few communities have been able to obtain this contract.

Some companies take shortcuts when acquiring land, with serious social and environmental consequences. Laws and policies regulating how companies obtain land are sometimes conflicting or inconsistent, leaving loopholes that companies can exploit to acquire land more quickly. Like Plantaciones de Pucallpa, which did not properly complete social and environmental licensing before beginning its operations, some companies take advantage of governments’ limited abilities to monitor for misconduct. This not only hurts communities, but also sets companies that do carefully screen for environmental and social risks at a competitive disadvantage compared to those taking shortcuts.

Getting to the Root of the Land Rights Problem

Investigating environmental crimes and problematic land transactions after they occur comes too late, and is expensive and time-consuming. A far better solution is to solve the land issues at the root of these problems. Governments should recognize indigenous and community land rights, engage in better monitoring of company misconduct during land acquisitions, and ensure that businesses secure the free, prior and informed consent of the people who live on the land before they begin operations.

LEARN MORE: Read the full report, The Scramble for Land Rights: Reducing Inequity Between Communities and Companies

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jun 29, 2018 | Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: The Yanomami are the largest relatively isolated indigenous people in the Amazon. © Fiona Watson/Survival

by Survival International

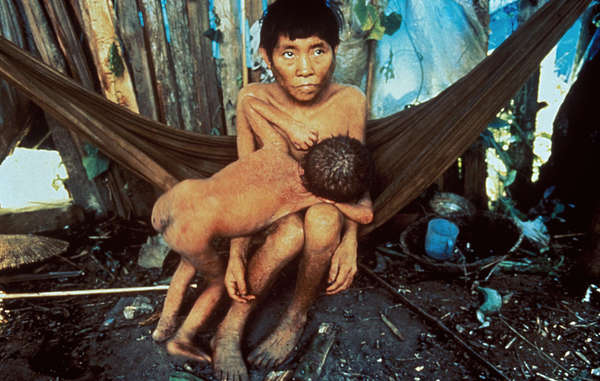

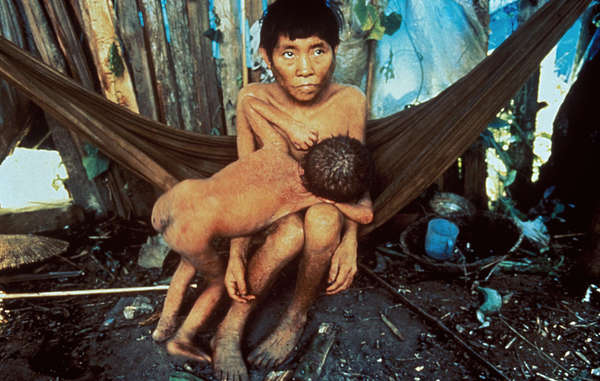

A measles epidemic has hit an isolated Amazon tribe on the Brazil-Venezuela border which has very little immunity to the disease.

The devastating outbreak has the potential to kill hundreds of tribespeople unless emergency action is taken.

Pictures of Yanomami affected by the current measles outbreak. © Wataniba

The Yanomami communities where the outbreak has occurred are some of the most isolated in the Amazon.

The Yanomami have previously been ravaged by outbreaks of deadly diseases following invasions of their territory by gold miners. © Antonio Ribeiro/Survival

But thousands of gold miners have invaded the region, and they are a likely source of the epidemic. Despite repeated warnings, the authorities have taken little effective action to remove them.

In Brazil, at least 23 Indians have visited a hospital, but most of those affected are far from medical care.

Previous disease outbreaks killed 20% of the Yanomami in Brazil. © Antonio Ribeiro/Survival

Survival International is calling for authorities in Venezuela to provide immediate medical assistance to these remote communities.

Survival’s Director Stephen Corry said today: “When tribal people experience common diseases like measles or flu which they’ve never known before many of them die, and whole populations can be wiped out. These tribes are the most vulnerable peoples on the planet. Urgent medical care is the only thing standing between these communities and utter devastation.”

The Venezuelan NGO Wataniba has released further details on the outbreak (in Spanish).

by DGR News Service | Jun 28, 2018 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change, Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy, Obstruction & Occupation

For Immediate Release

June 28, 2018

Activist risks arrest in front of Minnesota Public Utilities Commission Office during its final hearings to permit the Line 3 tar sands pipeline

Contact: Ethan Nuss, (218) 380-9047, stopline3mpls@gmail.com

ST PAUL, MN – A water protector ascended a 25-foot steel tripod structure erected in the street in front of the Public Utility Commission (PUC) office to demonstrate ongoing resistance against Enbridge’s proposed Line 3 tar sands pipeline. Today marks one of the final public hearings held by the PUC on its decision to grant a certificate of need to the controversial pipeline.

All five of the directly affected Objibwe Tribal Nations in Minnesota oppose the dangerous project because of the threat it poses to their fresh water, culturally significant wild rice lakes, and tribal sovereignty. Line 3 will accelerate climate change by bringing carbon-intensive tar sands bitumen from Alberta to refineries in the Midwest. Climate change disproportionately impacts Indigenous and frontline communities across the world. This deadly infrastructure project is another example of the genocidal legacy of colonialism faced by Native peoples and the ecological destruction caused by corporate greed. Water protectors, climate justice advocates, landowners, and faith leaders stand united alongside Native communities against this dangerous pipeline.

At around 7AM CST water protectors blockaded traffic by erecting 25-foot steel poles in a tripod structure on 7th Pl. in front of the PUC offices in downtown Saint Paul, MN. Ben, a 30-year-old Minneapolis resident, ascended the structure and unfurled a banner that reads, “Expect Resistance,” a clear message to Enbridge and the PUC that fierce opposition to this pipeline will continue to grow at every stage.

“If the PUC doesn’t stop Line 3, then we will,” said Ben, suspended from the 25-foot structure in the street in front the PUC. “Today’s action isn’t about me but is a demonstration of the growing resistance to Line 3. ” Ben continued, “We’re taking action in solidarity with Native people, who continue to fight for their existence on occupied land and with people all over the world who resist the desecration of nature by extractive industries.”

For photos and live updates go to: twitter.com/ResistLine3

(Update: the tripod was occupied for three years before being vacated)