By Will Falk / Deep Green Resistance

Featured image: Flag of the San Patricios, or “Saint Patrick’s Battalion.”

I do not know if my blood took sides. I do not know if I descend from those brave enough to fight back. I do not know, but the memories come easily enough.

I search, so I may claim the unbroken chains, stretching far into the past, that bind us to resistance.

I find Pádraig Pearse dressing himself in the early morning hours of Monday, April 24, 1916.

I see him struggling with the buttons on his shirt as his fingers shake with nerves. I hear him anxiously muttering the opening to the speech he would give on the grey steps of the General Post Office in Dublin just a few hours later, “Irishmen and Irishwomen! In the name of God and of the dead generations from which she receives her old tradition of nationhood…”

I assume he probably knew that in a few days a firing squad would add his body, his brother Willie’s body, and the bodies of his compatriots to the heaps of dead generations that formed Ireland’s centuries-old resistance to colonization. His eyes might have paused for a moment on his left breast pocket wondering if they’d even bother to pin a target there for the riflemen in Kilmainham Jail.

I see young Tommy Woods, a 17 year-old boy, who left Dublin to volunteer with a contingent of Irish fighters known as the Connolly Column resisting Franco with Spanish Republicans. I am with Woods as he presses his hands over his wounds trying to hold his pumping blood in. I listen as the last sound he hears are the engines of Franco’s bombers overhead.

I wonder if that’s what Guernica sounded like.

I feel the sun rise hot and sticky over Chapultepec in September, 1847. I watch as 29 Irishmen, members of the Mexican Army’s St. Patrick’s Brigade, stand on gallows with hands tied behind their backs waiting for the Mexican flag to be taken from the top of Chapultepec Castle, so they can be hanged as deserters at the precise moment the American flag is raised.

I grimace as an army surgeon informs Colonel William Harney that the 30th member of St. Patrick’s Brigade to be hanged, Francis O’Connor, had his legs amputated the day before. I hear Harney scream, what he was later quoted as screaming, “Bring the damned son of a bitch out! My orders were to hang 30 and by God I’ll do it!”

Some of the men roll their heads against the scratchy hemp of the nooses rubbing on their ruddy, sunburnt necks. Some of the men hold rosary beads. Some of the men are telling jokes. One man has already pissed his pants.

All of the men cheer when Mexican cadet Juan Escutia rips the Mexican flag from it’s pole atop Chapultepec Castle and leaps to his death on the battlements below depriving the Yankees of capturing the Mexican flag for themselves.

I am Irish. I am white. I recall Cambridge historian Charles Kingsley’s letter to his wife in 1860 when he wrote of the people he encountered in Ireland, “I am haunted by the human chimpanzees I saw along that hundred miles of horrible country…to see white chimpanzees is dreadful; if they were black one would not see it so much, but their skins, except where tanned by exposure, are as white as ours.”

Or, the statement from Queen Victoria’s economist, Nassau Senior, when he stated in 1848 at the height of the Great Famine, that existing policies, “will not kill more than one million Irish in 1848 and that will scarcely be enough to do much good.”

On the campus of the University of Notre Dame, where my father went to college, there is a statue depicting Father William Corby, one hand over his heart, one hand pointing at God, as he gives a sermon to the Union’s Irish Brigade of July 2, 1863. In the sermon, Father Corby warned troops that the Catholic Church forbade last rites and burial to soldiers who turned in the face of the slavers – enemy, Confederate soldiers – at Gettysburg. Father Corby, surviving the war, became the President of the University of Notre Dame.

Notre Dame students, forgetting Corby’s meaning and focused more on football, refer to the statue as “Faircatch Corby.”

A few years ago on St. Patrick’s Day, Subcomandante Marcos wrote, “When Mexico was fighting, in the last century, against the empire of the bars and crooked stars, there was a group of soldiers who fought on the side of the Mexicans and this group was called ‘St. Patrick’s Battalion’. And so I am writing you in the name of all of my companeros and companeras, because just as with the ‘Saint Patrick’s Battalion’, we now see clearly that there are foreigners who love Mexico more than some natives who are now in the government.”

I strive to remember the old alliances.

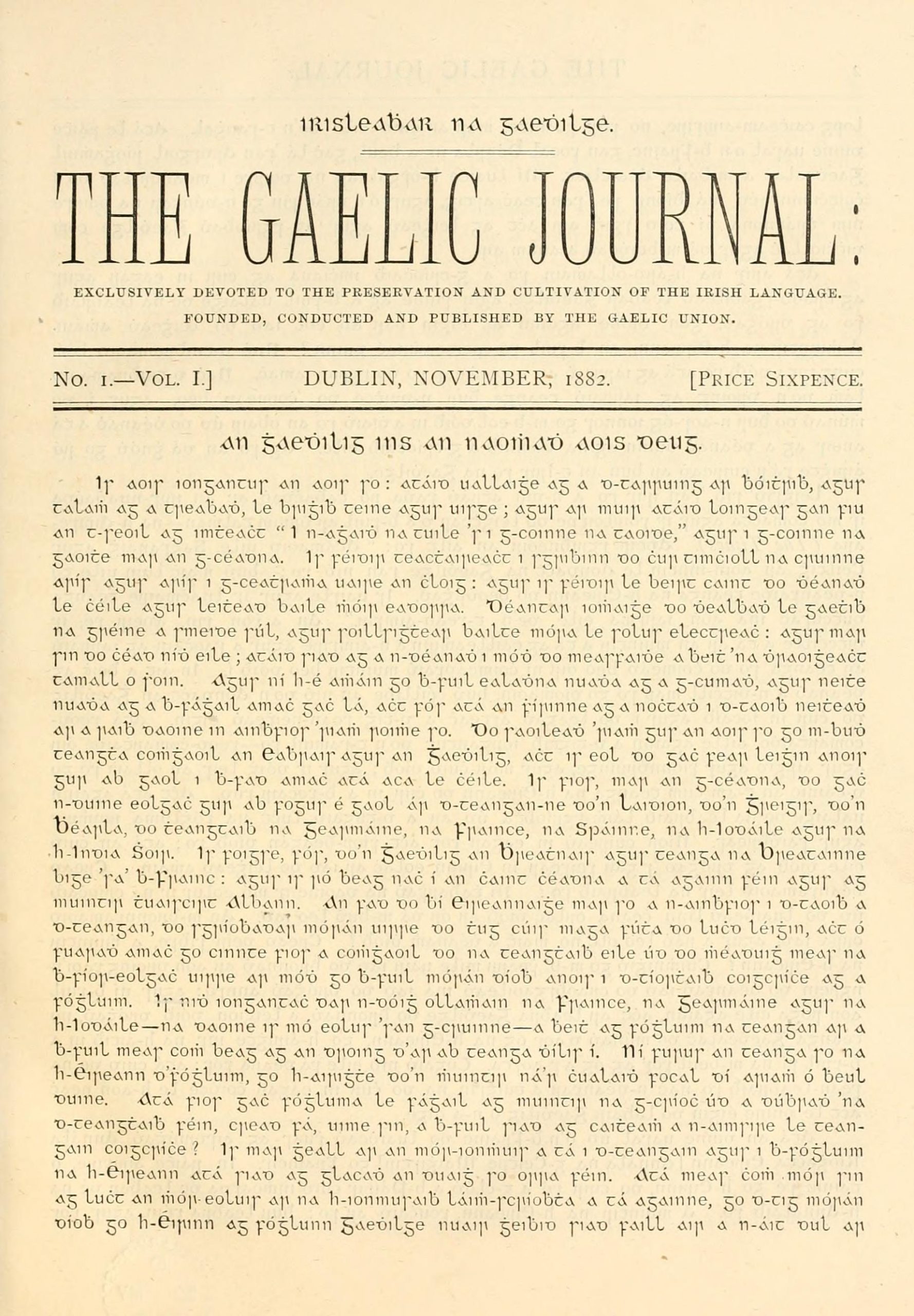

Edition of The Gaelic Journal published in 1882, part of the “Gaelic Revival.”

Author Bio

Will Falk is a writer, lawyer, and environmental activist. The natural world speaks and Will’s work is how he listens. He believes the ongoing destruction of the natural world is the most pressing issue confronting us today. For Will, writing is a tool to be used in resistance.

Will graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School and practiced as a public defender in Kenosha, WI. He left the public defender office to pursue frontline environmental activism. So far, activism has taken him to the Unist’ot’en Camp – an indigenous cultural center and pipeline blockade on unceded Wet’suwet’en territory in so-called British Columbia, Canada, to a construction blockade on Mauna Kea in Hawai’i, and to endangered pinyon-juniper forests in the Great Basin.

His writing has been published by CounterPunch, Earth Island Journal, CATALYST Magazine, Whole Terrain, Dark Mountain Project, the San Diego Free Press, and Deep Green Resistance News Service among others. His first book How Dams Fall: Stories the Colorado River Told Me was published in August, 2019 by Homebound Publications.

He lives in Castle Rock, Colorado.

I see the Irish troopers of the Horse Calvary, the wonderful 11 hand high hunters they rode! — massacering First Nations members after the Civl War. I see them fighting for and against slavery, I see them killinge each other. I see them as cops who areenemies of the working class and saving kids from drowning.

Many Irish did, and do, participate in genocide and colonization. This is unforgivable and I’m not trying to ignore them. My point with this piece was to point out that there were those who resisted, those who fought against evil. Milan Kundera said, “The struggle against oppression is the struggle of memory against forgetting.” If that’s true, then we can’t forget those of our ancestors who showed bravery and made sacrifices for the right causes.