by Deep Green Resistance News Service | May 31, 2016 | Agriculture, Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: Combine harvesters crop soybeans during a demonstration for the press, in Campo Novo do Parecis, Brazil, on March 27, 2012. By Phys.org.

By Manuela Picq / Intercontinental Cry

Soy has become quite fashionable as a “wonder food.” Praised for its nutritional values, soy has the highest protein content of any bean making it a favorite among vegans, animal defenders and even young hipsters who swear by their morning soy latte. For many, however, soy is an ethical and political choice. By switching to soy, we get to spare our bodies and the planet from the harmful effects of the meat and dairy industry, its extensive use of antibiotics and its heavy contribution to the ever-growing climate crisis.

The problem is, soy production is a veritable criminal enterprise. The impressive bean that so many of us love is grown by multinational corporations that poison soil and water with toxic agrochemicals. What’s more, the bean is a Monsanto genetically modified crop the full impacts of which are still unknown. Soy is also used extensively by livestock producers alongside genetically modified corn as a base for animal feed. On top of this toxic burden, the soy agribusiness industry expropriates Indigenous Peoples. Also it destroys forests. And, like the meat and dairy industry, it’s fueling the climate crisis.

Let’s take a closer look at these four interrelated reasons why we need to move away from soy, in its many forms.

1) THE EXPANSION OF SOY MONOCULTURE IS RESPONSIBLE FOR MASSIVE DEFORESTATION AND CLIMATE CHANGE

Growing soy requires vast extensions of land. In fact, it requires so much land that soy monoculture a leading factor in the destruction of the world’s biodiversity. Soy farms now cover more than one million square kilometers of the world – the total combined area of France, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands. The soy agriculture industry is having an especially devastating impact in Amazonia but also in the Cerrado and the Chaco. Almost 4 million hectares of forests are destroyed every year, 2.6 million in Brazil alone, the world’s leading soy producer.

Compounding this rampant devastation, when forests are transformed into farmland, soil quality deteriorates, leading to increased pollution, increased flooding and increased sedimentation that can clog waterways. This can cause a significant decline in fish populations and other life. Agrochemical residues degrade soil even further, along with the local water table and natural processes such as pollination. Such loss of biodiversity is a key factor of climate change.

2) THE GLOBAL SOY INDUSTRY HAS INDIGENOUS BLOOD ON ITS HANDS

The expansion of soy is made possible through land grabbing and by provoking land conflicts. Indigenous Peoples are often the main victims of this expropriation and dispossession and are often forced into urban poverty as a result. Indigenous resistance, however, is brutally repressed.

In Brazil, the Kaiowá-Guarani peoples have denounced over three hundred assassinations. Indigenous peoples defending their land are being killed by private militias hired by large soy corporations like Raizen, Breyfuss, Bunge, Syngenta and the French-Swiss Louis Dreyfus Commodities. “The soy you consume is stained with Guarani Kaiowá blood,” said Valdelice Veron, the daughter of cacique killed by a soy producer in 2003.

One emblematic case was the brutal homicide of a young leader in the state of Mato Grosso in 2014. Marinalva Kaiowá was stabbed 35 times only two weeks after defending the demarcation of Guyraroká lands in a court ruling at the federal Supreme Court in Brasilia. Her killing is, unfortunately, no exception. It is emblematic of a larger massacre. The Kaiowá-Guarani have a homicide rate nearly 500 times higher than the Brazilian average, exceeding that of countries at war.

One in two assassinations of Indigenous peoples in Brazil is related to the expansion of soy. The state of Mato Grosso do Sul, the world’s largest producer of soy, concentrates nearly 55 % of indigenous homicides in Brazil. Historian Marcelo Zelic told a special parliamentary commission that the state accounted for 377 of the 687 recorded cases of Indigenous peoples killed between 2003 and 2014. In other words, the state at the heart of soy’s agribusiness has a rate of Indigenous homicides three times higher than all other Brazilian states together.

Soy expansion is also forcing Indigenous peoples into smaller territories. There are 24 Indigenous territories in Mato Grosso do Sul, but lands for non-Indigenous peoples is 4 inhabitants per sq kilometers, 96 per sq/km for Terena Indians, and 34 per sq/km for the Guarani-Kaiowá.

The expansion of soy on Indigenous territories is feeding a devastating death toll and governments are often accomplice. In Brazil, Congress pleased the soy sector with a new bill (PEC 215) facilitating the redefinition of previously demarcated Indigenous territories into farmland. The law, accused of being unconstitutional, was designed to pursue an even more aggressive expropriation of Indigenous lands in Amazonia.

3) SOY IS A BILLION DOLLAR INDUSTRY THAT CONCENTRATES LAND AND ACCENTUATES INEQUALITY

Make no mistake. Soy is a massive commercial enterprise that is controlled by a few major landowners and corporations that don’t have our best interests at heart. In Brazil, many farms average 1,000 ha and some reach 50,000 ha (for the soccer aficionados out there, that is about 70,000 soccer fields). In Argentina, the world’s third producer after the USA, soy has replaced small farming, provoking rural migration to the cities and the disappearance of small towns in the Chaco region.

There are no labor benefits either. Since land is concentrated into the hands of few, mechanization drastically reduces farm jobs. When there is labor, it is prone to abuse. For instance, Greenpeace has documented workers being duped into coming to ranches where their papers are taken away and they are forced to work in soy farms.

4) SOY IS PLAIN BAD FOR YOUR HEALTH

Most soybeans are genetically modified to tolerate agrochemical farming, which means they are not only nutritionally inferior but also contain toxic chemicals. While there is little scientific data available on the physiological impacts of GMOs on the human body, GMO soy production is dependent on the heavy use of chemicals that poison our bodies and the environment. A study in Brazil’s Mato Grosso, for example, tested 62 samples of breast milk and found traces of one or more toxic agrochemicals in each and every sample. Not surprisingly, a documentary investigating the impacts of growing soy in South America to feed factory farms in Europe is called Killing Fields.

Monsanto crops have poisoned Argentina. The country’s entire soy crop is genetically modified which has skyrocketed the need for agrochemicals. Today, Argentine farmers apply an estimated 4.3 pounds of agrochemical concentrate per acre, more than twice what farmers in the U.S. rely on. The arrival of Monsanto crops brought birth defects and high rates of cancer among the rural population. But it doesn’t end there. Argentina exports most of its soy to Europe. If you live in Europe, chances are your morning soy latte and that tasty slice of in-house tofu cheesecake you had at lunch is made with Monsanto crops farmed in Argentina.

It’s almost impossible to avoid GM soy these days. Since it was first introduced in 1996, GM soy now dominates the industry comprising some 90% of all soy production. Countries like Argentina and the United States rely almost entirely on GM soy. More than a few local organic soybean businesses have collapsed because their soybeans were allegedly accidentally contaminated with patented strains of GM soy. Some claim that just 0.1% of world production is certified organic soy.

Soy is everywhere and we often eat it without our knowledge or consent. The overwhelming majority of the global soy production (80%) goes to feed animals, especially chickens and pigs, which means we are eating it too. The same goes for dairy products, since soy is also used in cattle feed. Soy is also the second most consumed oil in the world (after palm oil). If you check the labels in your kitchen cupboards you’re bound to find it.

It’s laudable to boycott the global cattle industry for its many harms to the earth, but we cannot reject one contaminating industry to endorse another. That is, unless our goal is to perpetrate a fraud at the expense of Indigenous Peoples, ecosystems and our own bodies.

If that’s not the sort of thing you can stomach we have no choice but to go conflict free. It’s not easy; but, then, nothing good in life ever is.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Feb 1, 2016 | Agriculture, Colonialism & Conquest

Featured image: Two Anuak women in the Gambella Province of Ethiopia. By Julio Garcia on March 18, 2007.

By Cultural Survival

On December 28, 2015 Ethiopia’s Agricultural Ministry revoked their contract with Karuturi Global Limited, an Indian company who in 2010 won a concession for 100,000 hectares of land to be developed for industrial agriculture for export in the Gambella region of southern Ethiopia, home to the Indigenous Anuak, Mezenger, Nuer, Opo, and Komo peoples. The Agricultural Ministry’s land investment agency cancelled the concession on the grounds that by 2012 Karuturi had developed only 1,200 hectares of land within the initial two year period of the contract.

Since 2013 the company began spiraling out of control, when it was found guilty of tax evasion in in a similar land grab venture in Kenya, and the following year had its operations was taken over by Stanbic Bank.

Karaturi’s Managing Director Sai Ramakrishna has challenged the Agricultural Ministry’s project termination in Ethiopia, telling Bloomberg Business, “I don’t recognize this cancellation,” and is seeking arbitration. If international arbitration is granted, Karuturi will advocate for the continuation of the company’s commercial agriculture plan. Ethiopian officials have dismissed their claims.

Karuturi Global’s project failure resembles that of many foreign investors who have purchased land under the Ethiopian government’s push to lease Indigenous lands to foreign investors, in what many term “land grabbing.” According to Bloomberg, none of these farms in Ethiopia have reported any success in exporting crops.

Ethiopia’s land leasing plans were described as a roadmap to development. Called “villagisation,” the plan involved removing the Indigenous Peoples who sustain themselves from their lands practising farming, hunting, gathering, and pastoralism, and grouping them into established villages, with the idea that the land would be used to produce large scale industrial agriculture to sustain the population’s food needs. Jobs would be created, turning Indigenous Peoples into wage workers who could then buy foods. But Karaturi’s plans were different–aiming to export grains for sale abroad rather than selling them locally, despite Ethiopia’s ban on the export of cereal crops.

The socio-economic transformation promised by the regional government was never realized. Rather, villagisation has meant the forced removal of Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral lands and the creation of an aid-dependant food source. Obang Metho, Anuak human rights activist from Gambella, explained in a video with local media Ethiopian Satellite Television, “This was not empty land. People have been living on this land for generations. When I grew up we didn’t have an office job to earn wages, people depend on land. Our supermarket is going to the field. The field was our bank. When you take away our lands, you are taking away our livelihood, our futures.”

An aerial view of the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya where many Anuak people turned to for shelter after forced removal from Gambella. Photograph taken on November 1, 2011 by Oxfam International

On a morning in late 2010 the Anuak peoples living in the province of Gambella were met by regional government officials and soldiers. Without their knowledge or consent the Ethiopian government had sold an estimated 42% of Anuak land to foreign investors. The Anuak people were forced to leave their only known livelihoods, including essential food sources, and move to government sponsored “villages” which soon turned into refugee camps. In 2012, Human Rights Watch published its report, “’Waiting Here for Death’ Forced Displacement and “Villagization” in Ethiopia’s Gambella Region” documenting the “forcible moving tens of thousands of indigenous people in the western Gambella region from their homes to new villages under a ‘villagization’ program.”

“In their old village there was a school under a mango tree. In the new village, donor money had paid for a new school building. The children, however, were too hungry to attend, roaming instead in the forest looking for food… but now the government can show the world there is a ‘school’” –Anuak refugee displaced to the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya (from The Guardian’s article, Ethiopia’s rights abuses ‘being ignored by US and UK aid agencies’.)

Since their displacement in 2010 the Anuak have become refugees – many having turned to the crowded refugee camps in South Sudan and Kenya. As a result of their forced displacement many of the Anuak, and other Indigenous Peoples of the southwest, have endured scores of human rights violations including documented cases of rape, torture, extrajudicial imprisonment and famine, while these conditions were ignored by donor agencies USAID and DfiD.

Now, Ethiopia, USAID and Dfid have a chance to right their wrongs, and return the lands to the Indigenous Peoples turned into development refugees. But the Agriculture Ministry has said that the rest of the land will return to a “land bank” for future re-investment.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples clearly states in Article 28.1

Indigenous peoples have the right to redress, by means that can include restitution or, when this is not possible, just, fair and equitable compensation, for the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned or otherwise occupied or used, and which have been confiscated, taken, occupied, used or damaged without their free, prior and informed consent.

For the survival of the Indigenous Peoples of Gambella, International aid agencies must take an active role to bring these displaced communities access to lands and a means of sustainable livelihoods.

by Deep Green Resistance News Service | Jan 10, 2016 | Agriculture, Colonialism & Conquest

By Mary Louisa Cappelli, PhD, JD / Globalmother.org

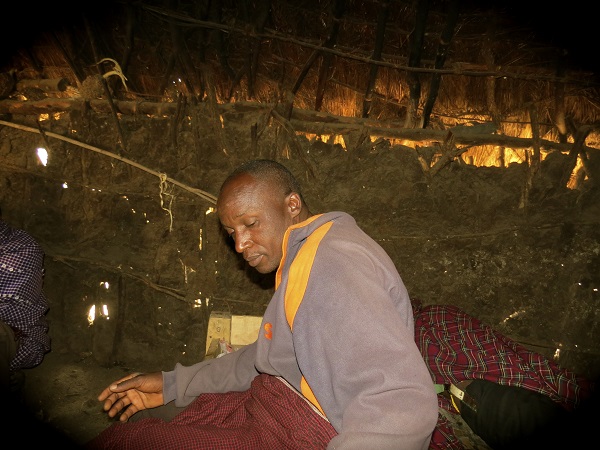

Featured image: Barabaig pastoralist

Katesh — After a fifty-year struggle against land grabbing by foreign agribusiness corporations, nomadic pastoralists in the Hanang District of Eastern Tanzania have finally won Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy pursuant to the 1999 Land Act No. 5. With legal assistance from The Ujamaa Community Resource Team, The Barabaig and Masai in the villages of Mureru, Mogitu, Dirma, Gehandu and Miyng’enyi now have much needed access to approximately 5,500 hectares of grazing land for their cattle.

While several villages have benefited from the decision to enforce the 1990 Land Act No. 5, the Barabaig of the Basuto Plains have not been recognized in the latest issuance of Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy. The Barabaig have been engaged in a fifty-year struggle to maintain their cultural integrity against the jurisprudent land policies of privatization and villagization, which have systematically suspended their constitutional rights and legal protections. The powerful infiltration of neoliberal forces culminating in land and resource grabbing has fashioned a geographical landscape of displaced indigenous peoples struggling to restructure their lives in uninhabitable terrain that supports relatively few life forms. While recording mythohistories amongst the Barabaig women, I have had the opportunity to witness first hand how the Barabaig have resisted globalizing forces that have pushed them to the farthest regions of the Basuto Plains.

Barabaig drinking from what remains of sole water source

Land Policy

The restructuring of socio-geographic areas in the interest of globalization has been most visible in the legal system in regards to land policy jurisprudence and administration, demonstrating how global discourse circulates in such a powerful system as to suspend constitutional rights and protections of the Barabaig Peoples. For many years, first President of the United Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere’s philosophy on land holdings has shaped Tanzanian land policy. Rejecting the commoditization of land, Nyerere believed land was God’s gift to humanity and therefore could not be privatized. In his discussion of land holdings, he argues:

This land is not mine, but the efforts made by me in clearing that land enable me to lay claim of ownership over the cleared piece of ground. But it is not really the land itself that belongs to me but only the cleared ground, which will remain mine as long as I continue to work on it. By clearing that ground I have actually added to its value and have enabled it to be used to satisfy a human need. Whoever then takes this piece of ground must pay me for adding value to it through clearing it by my own labour. (Nyerere 1966)

This philosophy treats land as a fundamental right of human needs and not as commodity. This sentiment is further expressed in “The Nyerere Doctrine of Land Value” in the case of Attorney- General v. Lohay Akonaay and Another (Sabine 1964). [i] Accordingly, it is the public who possess land rights and an individual has a right to occupancy to use the common land belonging to the public. The duration of the Right to Occupancy can last from anywhere between 33 to 99 years depending on location and usage. The 1923 Land Ordinance of 1923 to 1999 referred to this title as a Deemed Right of Occupancy, based on occupation to confer ownership. “The majority of the people living in the rural areas—and who form more that 80% of the population of Tanzania hold their land under this system” (Peter 2007).

Today, President John Magufuli is the trustee of Tanzanian public lands and it is Magufuli who has the power and authority to decide what is in the public’s interest in terms of land decisions. Magufuli holds the power to “repossess land on behalf of the public for construction of roads, schools, hospitals etc.” (Peter 2007). Land can and has been taken from indigenous peoples without compensation for the land. In return the occupier is compensated for unexhausted improvements to the land, including houses, structures, crops; however, the occupier is not compensated for the land itself.

Legal Decisions Support Agribusiness Ventures

The implementation of the commoditization of land and resources can be seen in the 1960 decision to cultivate wheat in the Arusha Region of Hanang District. The United Republic of Tanzania along with the Canadian Food Aid Programme launched the Basotu Wheat Complex securing ten thousand acres of Barabaig land for wheat farming. In 1970, the National Agriculture and Food Corporation (NAFCO) expanded the project developing several large scale wheat farms securing 120,000 hectares of Barabaig pasture land, including homesteads, water sources, sacred burial grounds, and wild life.

Sadly, many Barabaig were unaware of the legal maneuvering for their land and first found out about it when tractors ploughed through their homesteads. According to reports and interviews, NAFCO failed to give due process to people living on their land at the time and were deemed to be trespassers on their own property. Chief Daniel recalls how he was jostled from sleep and ordered to leave. “We were forced off our own land by gunpoint,” he said.

A girgwagedgademga (council of women) with Chief Daniel

In the 1981 Case of National Agricultural and Food Corporation v. Mulbadaw Village Council and Others, the Barabaig sought legal protection and sued the National Agricultural and Food Corporation (NAFCO) for trespass on their land at the High Court of Tanzania in Arusha. While the High Court of Tanzania (D`Souza, Ag. J.) ruled in favor of the Barabaig Plaintiffs, stating that the Barabaig occupied land under customary title, the Court of Appeal of Tanzania overturned the decision and ruled in favor of NAFCO stating that, “The Plaintiffs/Respondents – Mulbadaw Village Council did not own the land in dispute or part of it because they did not produce any evidence to the effect of any allocation of the said land in dispute by the District Development Council as required by the Villages and Ujamaa Villages Act of 1975” (Peter 2007). In effect, the Village Council had trespassed by entering their own traditional lands, the Court of Appeals ruling that the villagers failed to meet the burden of proof that they were natives within the meaning of the law.

Legal analysis of case precedence is evidence that the Tanzanian government discounted Barabaig collective customary rights, discounted Barabaig tripartite land holding practices, ignored detrimental ecological effects derived from alienation of pastoral lands, and moreover privileged the privatization and commodification of land and foreign and national interests over local indigenous rights. Political power backed by powerful interest groups proved in this case study that power is not the same as law and that in the world of nation-states, placelessness and dispossession is a political byproduct of globalization.

In 1987, Tanzania, submitting to pressure to follow “global norms of behaviour,” decreed the Extinction of Customary Land Right Order. This extinguished land occupation under customary law, precluding Barabaig from exercising customary land rights protection (Larson and Aminzade 2009). Subsequently, when the Barabaig migrated during dry seasons, they left their lands with little evidence of occupancy, resulting in encroachment by external forces. The government began the process of Villagization, whereby the Barabaig were given portions of unused land deemed unsuitable for commercial purposes with little water resources. The Barabaig were subsequently settled (land-locked) in villages. The Villagization of the Barabaig drastically interfered with customary land practices, nomadic land use patterns, and livestock herding traditions.

According to Shivjii Chairman of the Presidential Commission of Enquiry into Land Matters, the movement of people into villages was achieved with “little regard to existing land tenure systems and the culture and custom in which they are rooted” (2007). The Barabaig surrendered their traditional migratory herding strategies and were forced to graze their cattle in a migratory cycle marked by a restricted one-day distance from their homestead. The concentration of livestock on this pattern of limited grazing has adversely impacted its ecosystems resulting in a “decline of levels of pastoral production and welfare” (Peter 2007).

Mama Paulina and widow

The Land Tenure reform is based on the premise that indigenous land tenure systems act as an obstruction to development and that more formal registered land title will encourage rural land users to make investments to improve their land investments through the provision of credit. The Tanzanian administrative structure grants each village a statutory title to land and further argues that granting titles and providing credit for land improvements will thwart encroachment by external forces; however, under the Customary Land Ordinance this has led to the holding of double titles leading to further complications of legality of ownership. The Barabaig case provides contrary evidence demonstrating that both objectives have failed to ward off encroachment by outsiders to enclose land for crop cultivation.

In addition, Land Use Appropriation by Foreign interests have interfered with traditional migratory patterns to water sources, denying Barabaig access to water during the dry seasons. Traditionally, Barabaig herders migrated eastward out of the village in the dry season to gain access to permanent water sources on the shores of Lake Balangda Lelu. The land allocation plans fail to recognize the indigenous needs of water sources; moreover, these allocations do not take into account the complexity of the traditional land use patterns in and beyond village boundaries. Because the Barabaig follow an animistic belief system that recognizes the interdependency and reverence of all life forms, displacement from their land and ancestral gravesites disrupts their sacred patterns of worship and traditional ways of being and living in the world.

The Barabaig were unaware of the Land Use Planning Provisions at the time and hence did not object to them because they did not realize how it would limit their migratory grazing patterns and obstruct their traditional livelihoods. According to Barabaig Chief Leader Daniel, plans were purposefully “ambiguous” and unclear with little account taken of their pastoral economy. Facing starvation, many pastoralists experienced a sense of cultural, spiritual and economic placelessness, and have been forced to give up their livelihood and migrate to squatter settlement areas in Arusha or Dar es Salam. “They fill the perio-urban shanties to eke out a living as best they can in the informal economy or become burdens of the state as the industrial and commercial sectors have no capacity to absorb more workers” (Lane 1990).

The issuance of Certificates of Customary Right of Occupancy provides a temporary legal tourniquet against the inhumane assault on indigenous livelihoods. According to Attorney Edward Ole Lekaita from The Ujamaa Community Resource Team in the Arusha District, efforts have begun once again to take up the legal gamut to secure customary title deeds for the Barabaig of the Basuto plains.

About the author: An interdisciplinary ethnographer, Mary Louisa Cappelli is a graduate of USC, UCLA, and Loyola Law School whose research focuses on how indigenous peoples of the global South struggle to hold onto their cultural traditions and ways of life amidst encroaching capital and globalizing forces. She previously taught in the Interdisciplinary Program at Emerson College and is the director of Globalmother.org, a Tanzanian WNGO, which engages in participatory action research and legislative advocacy in Africa and Central America.

References:

Aminzade, R. and Larson, E. “Nation-building in post-colonial nation-states: the cases of Tanzania and Fiji.” International Social Science Journal Vl. 59: (2009):1468-2451.

Lane, R. Charles. “Barabaig Natural Resource Management: Sustainable Land use under Threat of Destruction.” United Nations Research Institute for Social Development Discussion. Discussion Paper (1990): No 12.

Nyerere, J. K. Freedom and Unity: A Selection from Writings and Speeches

1952-1965. London: Oxford University Press, 1966.

Peter, Maina, Chris. “Human Rights of Indigenous Minorities in Tanzania and the Court of Law.” Journal of Group and Minority Rights, 2007.

Sabine, G. H. A History of Political Theory, London: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd, (1964): 527-528.

by DGR Colorado Plateau | Oct 23, 2015 | Agriculture

Biotech and Food Industries Stack Hearing on H.R. 1599 with Pro-GMO Witnesses

By Organic Consumers Association

FINLAND, Minn. – The Organic Consumers Association (OCA) issued this statement today, following a hearing by the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition & Forestry on H.R. 1599, a bill that would preempt state and federal rights to enact laws requiring mandatory labeling of genetically engineered foods or foods containing genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Ronnie Cummins, international director, said:

Today’s hearing on H.R. 1599 made a total mockery of democracy. Of the eight witnesses allowed to testify, only one could be remotely considered as someone who represents the interests of consumers and public health. The other seven have ties to the biotech and corporate food industries, and were there to represent the interests of corporations, not people.

Today, we call on millions of American consumers to contact their elected officials with this message: If you vote against states’ rights, if you vote against truth and transparency in labeling, if you vote against the more than 90 percent of Americans who want mandatory, not voluntary, labeling of GMO foods, we will vote against you.

The OCA was not invited to testify at today’s hearing. Here is the list of witnesses, and their affiliations.

• Michael Gregoire, associate administrator, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

Gregoire helped Monsanto by cutting in half the time it takes for the USDA to rubber-stamp a new GMO crop.

• William Jordan, deputy director, Office of Pesticide Programs, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Jordan oversaw the EPA’s reaction to the infamous StarLink GMO contamination scandal in 2000. The StarLink corn variety, engineered to produce a Bt toxin, was supposed to be limited to animal feed and industrial use out of fear it might cause severe allergic reactions. But it turned up in taco shells, and people started getting sick. Jordan refused to punish StarLink producer Aventis with even so much as a fine.

• Susan Mayne, director, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, FDA

Mayne leads the FDA division that has the power to require labeling of genetically engineered foods (as long as the DARK Act doesn’t pass), but we don’t know where she stands on consumers’ right to know. Mayne came to the FDA just this year from the Yale Cancer Center. As the associate director of the Yale Cancer Center, Mayne was critical of research showing an 87-percent higher pancreatic cancer risk among regular soda drinkers. Mayne published her own research that disputed links between soda consumption and esophageal cancer. Most soda contains high fructose corn syrup made from GMO corn.

• Joanna Lidback, producer, The Farm at Wheeler Mountain, Barton, Vt.

Lidback is a graduate of the American Farm Bureau’s Monsanto-funded Partners in Agricultural Leadership program. Lidback has an MBA and works full-time as a business consultant to Yankee Farm Credit. She is the first vice president of the Orleans County Farm Bureau. She’s on the board of directors of the Truth About Trade & Technology. Lidback also represents Agri-Mark, the National Council of Farmer Cooperatives, and the National Milk Producers Federation, as a dairy farmer producing milk for Cabot Cheese. Vermont’s GMO labeling law won’t impact Lidback’s farm because it doesn’t cover the products of animals fed genetically engineered feed, but Lidback is expected to falsely claim that the law will put her farm out of business.

• Daryl E. Thomas, senior vice president, Herr Foods, Inc., Nottingham, Pa.

Herr Foods represents the typical food company that wants to make money from the market for non-GMO foods, while keeping consumers in the dark about which foods contain GMO ingredients. On Herr’s website, the company explains its twisted position this way: “We know that food safety is paramount to everyone. So while we continue to explore opportunities to offer the latest developments in non-GMO ingredients, we remain committed to delivering to you the safest and best tasting snacks possible.” Herr’s recently began marketing a non-GMO popcorn called Go-Lite! Herr’s has been lobbying against mandatory GMO labels with the Snack Foods Association.

• Gary Hirshberg, chairman and co-founder, Stonyfield Farm Inc., Concord, N.H.

Hirshberg is the only witness from “our side.”

• Gregory Jaffe, project director, Biotechnology, Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI)

CSPI opposes GMO labels and safety testing. CSPI supports legislation introduced by Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) in 2004 which was intended to permanently change the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act so that it “does not subject most genetically engineered foods to the lengthy food additive approval process.” Sen. Durbin’s bill is a tacit acknowledgement that GMOs are supposed to go through the food additive approval process, and an admission that in order to exempt Monsanto from that requirement, the law must change. As Steven Druker explains in his book, “Altered Genes, Twisted Truth,” in 1992, the FDA illegally exempted GMOs from the food additive approval process which requires new additives to food be demonstrated safe before they are marketed to the public. H.R. 1599 would enshrine in permanent law the FDA’s 1992 Guidance to Industry for Foods Derived from New Plant Varieties, which allows companies to go through a consultation process that the agency admits doesn’t determine the safety of new GMOs.

• Ronald E. Kleinman, physician in chief, MassGeneral Hospital for Children, Boston, Mass.

Michele Simon exposed Kleinman in 2012 when he worked for the GMO junk food industry during the Prop 37 campaign to label GMOs in California. Kleinman presents webinars on children’s health, forCoca-Cola. Among the “most common misperceptions among parents” Dr. Kleinman promises to clear up on behalf of the soda giant are “the safety … of sugar, artificial colors and nonnutritive sweeteners in children’s diets.” His bio on the Massachusetts General Hospital webpage says he consults for the Grain Food Foundation, Beech Nut, Burger King, and General Mills. According to CSPI, (which is good on everything but GMOs), Kleinman served as a paid expert witness for Gerber when the company was sued for deceptive advertising, and he contributed to a children’s brochure entitled “Variety’s Mountain” produced by the Sugar Association.

The Organic Consumers Association (OCA) is an online and grassroots non-profit 501(c)3 public interest organization campaigning for health, justice, and sustainability. The Organic Consumers Fund is a 501(c)4 allied organization of the Organic Consumers Association, focused on grassroots lobbying and legislative action.

by DGR Editor | Sep 27, 2015 | Agriculture, Indigenous Autonomy

by Kim Hill, Deep Green Resistance Australia

Why did the Australian aborigines never develop agriculture?

This question was posed in the process of designing an indigenous food garden, and I could hear the underlying assumptions of the enquirer in his tone. Our culture teaches that agriculture is a more desirable way to live than hunting and gathering, and agriculturalist is more intelligent and more highly evolved than a hunter gatherer.

These assumptions can only be made by someone indoctrinated by civilization. It’s a limited way to look at the world.

I was annoyed by question, and judged the person asking it as ignorant of history and other cultures, and unimaginative. Since many would fit this label, I figured I’m better off answering the question.

This only takes some basic logic and imagination, I have no background in anthropology or whatever it is that would qualify someone to claim authority on this subject. You could probably formulate an explanation by asking yourself: How and why would anyone develop agriculture?

First consider the practicalities of a transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture.

What plants would be domesticated? What animals? What tools would they use? How would they irrigate?

Why would anyone bother domesticating anything that is plentiful in the wild?

To domesticate a plant takes many generations (plant generations, and human generations) of selecting the strongest specimens, propagating them in one place, caring for them, protecting them from animals and people, from the rain and wind and sun, keeping the seeds safe. This would be incredibly difficult to do, it would take a lot of dedication, not just from one person but a whole tribe for generations. If your lifestyle is nomadic, because food is available in different places in different seasons, there is no reason to make the effort to domesticate a plant.

Agriculture is high-risk. There are a lot of things that could destroy a whole crop, and your whole food supply for the year, as well as your seed stock for the next. A storm, flood, fire, plague of insects, browsing mammals, neighbouring tribes, lack of rain, disease, and no doubt many other factors. A huge amount of work is invested in something that is likely to fail, which would then cause a whole community to starve, if there isn’t a back-up of plentiful food in the wild.

Agriculture is insecure. People in agricultural societies live in fear of crop failure, as this is their only source of food. The crops must be defended. The tools, food storage, water supply and houses must also be defended, and maintained. Defended from people, animals, and insects. Growing and storing all your food in one place would attract all of these. Defence requires weapons, and work.

Agriculture requires settlement. The tribe must stay in one place. They cannot leave, even briefly, as there is constant maintenance and defending to do. Settlements then need their own infrastructure: toilets, water supply, houses, trading routes as not all the food needs can be met from within the settlement. Diseases spread in settled areas.

Aboriginal people travel often, and for long periods of time. Agriculture is not compatible with this way of life.

Agriculture is a lot of work. The farmers must check on the crop regularly, destroy diseased plants, remove weeds, irrigate, replant, harvest, save seeds, and store the crop. Crops generally are harvested for only a few weeks or months in the year, and if they are a staple, must be stored safely and be accessible for the rest of the year.

Domesticated animals require fencing, or tethering, or taming. They would be selectively bred for docility, which is a weakness not a strength, so a domesticated animal would be less healthy than a wild animal.

The people too become domesticated and lose strength with the introduction of agriculture. The wild intelligence needed to hunt and gather would be lost, as would the relationships with the land and other beings.

Agriculture requires a belief in personal property, boundaries, and land ownership. Australian aborigines knew that the land owned the people, not the other way around, so would never have treated the land in this way.

Agriculture needs a social hierarchy, where some people must work for others, who have more power by having more wealth. The landowner would have the power to supply or withhold food. Living as tribal groups, aborigines probably wouldn’t have desired this social structure.

Cultivated food has less nutrition than wild food. Agriculturalists limit their diet to plants and animals that can easily be domesticated, so lose the diversity of tastes and nutrients that make for an ideal human diet. Fenced or caged animals can only eat what is fed to them, rather than forage on a variety of foods, according to their nutritional needs. Domesticated plants only access the nutrients from the soil in the field, which becomes more depleted with every season’s crop. Irrigation causes plants to not send out long roots to find water, so domesticated plants are weaker than wild plants.

Agriculture suggests a belief that the world is not good enough as it is, and humans need to change it. A land populated with gods, spirits or ancestors may not want to be damaged, dug, ploughed and irrigated.

Another thought is that agriculture may develop from a belief in scarcity – that there is not enough food and it is a resource that needs to be secured. Indigenous belief systems value food plants and animals as kin to be in relationship with, rather than resources to exploit.

Agriculture isn’t an all-or-nothing thing. Indigenous tribes engage with the landscape in ways that encourage growth of food plants. People gather seeds of food plants and scatter them in places they are likely to grow. Streams are diverted to encourage plant growth. Early explorers witnessed aboriginal groups planting and irrigating wild rice. Tribes in North Queensland were in contact with Torres Strait Islanders who practiced gardening, but chose not to take this up on a large scale themselves.

A few paragraphs from Tim Low’s Wild Food Plants of Australia:

The evidence from the Torres Strait begs the question of why aborigines did not adopt agriculture. Why should they? The farming life can be one of dull routine, a monotonous grind of back-breaking labour as new fields are cleared, weeds pulled and earth upturned. The farmer’s diet is usually less varied, and not always reliable, and the risk of infectious disease is higher…It is not surprising that throughout the world many cultures spurned agriculture.

Explorer Major Mitchell wrote in 1848: ‘Such health and exemption from disease; such intensity of existence, in short, must be far beyond the enjoyments of civilized men, with all that art can do for them; and the proof of this is to be found in the failure of all attempts to persuade these free denizens of uncivilized earth to forsake it for tilled soil.’

After all this, I’m amazed that anyone ever developed agriculture. The question of why Australian aborigines never developed agriculture is easily answered and not as interesting as the question it brings up for me: why did twentieth century westerners never develop hunter-gatherer lifestyles?

From Stories of Creative Ecology January 5, 2013

by DGR Editor | Aug 25, 2015 | Agriculture, Listening to the Land, Male Supremacy, Male Violence, Rape Culture, Women & Radical Feminism

Captured in a test tube, blood may look like a static liquid, but it’s alive, as animate and intelligent as the rest of you. It also makes up a great deal of you: of your 50 trillion cells, one-quarter are red blood cells. Two million are born every second. On their way to maturation, red blood cells jettison their nuclei―their DNA, their capacity to divide and repair. They have no future, only a task: to carry the hemoglobin that will hold your oxygen. They don’t use the oxygen themselves–they only transport it. This they do with exquisite precision, completing a cycle of circulation through your body every twenty seconds for a hundred days. Then they die.

The core of hemoglobin is a molecule of iron. It’s the iron that grasps the oxygen at the surface of your lungs, hangs on through the rush of blood, then releases it to wanting cells. If iron goes missing, the body, as ever, has a fallback plan. It adds more water to increase blood volume; thin blood travels faster through the fine capillaries. Do more with less.

All good except there’s less and less oxygen offered to the cells. Another plan kicks in: increased cardiac output. The heart ups its stroke volume and its rate. To keep you from exploding, the brain joins in, sending signals to the muscles enfolding each blood vessel, telling them to relax. Now blood volume can increase with blood pressure stable.

But still no iron arrives. At this point, the other organs have to cooperate, giving up blood flow to protect the brain and heart. The skin makes major sacrifices, which is why anemics are known for their pallor. Symptoms perceived by the person―you―will probably increase as your tissues, and then organs, begin to starve.

If there is no relief, ultimately all the plans will fail. Even a strong heart can only strain for so long. Blood backs up into the capillaries. Under the pressure, liquid seeps out into surrounding tissues. You are now swelling and you don’t know why. Then the lungs are breached. The alveoli, the tiny sacs that await the promise of air, stiffen from the gathering flood. It doesn’t take much. The sacs fill with fluid. Your body is drowning itself. This is called pulmonary edema, and you are in big trouble.

I know this because it happened to me. Uterine fibroids wrung a murder scene from me every month; the surgery to remove them pushed me across the red cell Rubicon. I knew nothing: my body understood and responded. My eyes swelled, then my ankles, my calves. Then I couldn’t breathe. Then it hurt to breathe. I finally stopped taking advice from my dog―Take a nap! With me!–and dragged myself to the ER, where, eventually, all was revealed.

Two weeks later, the flood had subsided, absorbed back into some wetland tissue of my body, and I felt the absence of pain as a positive. Breathing was exquisite, the sweetest thing I could imagine. Every moment of effortless air was all I could ever want. I knew it would fade and I would forget. But for a few days, I was alive. And it was good.

Our bodies are both all we have and everything we could want. We are alive and we get to be alive. There is joy on the surface of the skin waiting for sunlight and soft things (both of which produce endorphins, so yes: joy). There is the constant, stalwart sound of our hearts. Babies who are carried against their mothers’ hearts learn to breathe better than those who aren’t. There is the strength of bone and the stretch of muscle and their complex coordination. We are a set of electrical impulses inside a watery environment: how? Well, the nerves that conduct the impulses are sheathed by a fatty substance called myelin―they’re insulated. This permits “agile communication between distant body parts.” Understand this: it’s all alive, it all communicates, it makes decisions, and it knows what it’s doing. You can’t possibly fathom its intricacies. To start to explore the filigree of brain, synapse, nerve, and muscle is to know that even the blink of your eyes is a miracle.

Our brains were two million years in the making. That long, slow accretion doubled our cranial capacity. And the first thing we did with it was say thank you. We drew the megafauna and the megafemales, sculpted and carved them. The oldest known figurative sculpture is the Goddes of Hohle Fels, and 40,000 years ago someone spent hundreds of hours carving Her. There is no mystery here, not to me: the animals and the women gave us life. Of course they were our first, endless art project. Awe and thanksgiving are built into us, body and brain. Once upon a time , we knew we were alive. And it was good.

__________

And now we leave the realm of miracles and enter hell.

Patriarchy is the ruling religion of the planet. It comes in variations―some old, some new, some ecclesiastical, some secular. But at bottom, they are all necrophilic. Erich Fromm describes necrophilia as “the passion to transform that which is alive into something unalive; to destroy for the sake of destruction; the exclusive interest in all that is purely mechanical.” In this religion, the worst sin is being alive, and the carriers of that sin are female. Under patriarchy, the female body is loathsome; its life-giving fat-cells vilified; its generative organs despised. Its natural condition is always ridiculed: normal feet must be turned into four-inch stubs; rib cages must be crushed into collapse; breasts are varyingly too big or too small or excised entirely. That this inflicts pain―if not constant agony―is not peripheral to these practices. It’s central. When she suffers, she is made obedient.

Necrophilia is the end point of sadism. The sadistic urge is about control–“the passion to have absolute and unrestricted control over a living being,” as Fromm defined it. The objective of inflicting pain and degradation is to break a human being. Pain is always degrading; victimization humiliates; eventually, everyone breaks. The power to do that is the sadist’s dream. And who could be more broken to your control than a woman who can’t walk?

Some nouns: glass, scissors, razors, acid. Some verbs: cut, scrape, cauterize, burn. These nouns and verbs create unspeakable sentences when the object is a seven-year-old girl with her legs forced open. The clitoris, with its 8,000 nerve endings, is always sliced up. In the most extreme forms of FGM, the labia are cut off and the vagina sewn shut. On her wedding night, the girl’s husband will penetrate her with a knife before his penis.

You don’t do this to a human being. You do it to an object. That much is true. But there is more. Because the world is full of actual objects—cardboard boxes and abandoned cars—and men don’t spend their time torturing those. They know we aren’t objects, that we have nerves that feel and flesh that bruises. They know we have nowhere else to go when they lay claim to our bodies. That’s where the sadist finds his pleasure: pain produces suffering, humiliation perhaps more, and if he can inflict that on her, it’s absolute proof of his control.

Behind the sadists are the institutions, the condensations of power, that hand us to him. Every time a judge rules that women have no right to bodily integrity—that upskirt photos are legal, that miscarriages are murder, that women should expect to be beaten—he wins. Every time the Fashion Masters make heels higher and clothes smaller, he smiles. Every time an entire class of women—the poorest and most desperate, at the bottom of every conceivable hierarchy—are declared legal commodities for sex, he gets a collective hard-on. Whether he personally uses any such women is beside the point. Society has ruled they are there for him, other men have ensured their compliance, and they will comply. He can kill one—the ultimate sex act for the sadist—and no one will notice. And no one does.

There is no stop to this, no natural endpoint. There is always another sentient, self-willed being to inflame his desire to control, so the addiction is forever fed. With other addictions, the addict bottoms out, his life becomes unmanageable, and the stark choice is stop or die. But the sadist isn’t hurting himself. There’s no looming bottom to hit, only an endless choice of victims, served up by the culture. Women are the feast at our own funeral, and he is happy to feed.

_____

If feminism was reduced to one word, it would be this: no. “No” is a boundary, spoken only by a self who claims one. Objects have neither; subjects begin at no. Feminists said no and we meant it.

The boundary of “no” extended outward, an insult to one being an injury to all: “we” is the word of political movements. Without it, women are cast adrift in a hostile, chaotic sea, holding our breath against the next Bad Thing. With the lens of feminism, the chaos snaps into sharp focus. We gave words to the Bad Things, then faced down denial and despair to see the pattern. That’s called theory. Then we demanded remedies. That’s what subjects, especially political subjects, do. Emmeline Pankhurst, leader of the British suffragettes, worked at the Census Office as a birth registrar. Every day, young girls came in with their newborns. Every day, she had to ask who the father was, and every day the girls wept in humiliation and rage. Reader, you know who the fathers were. That’s why Pankhurst never gave up.

To say no to the sadist is to assert those girls as political subjects, as human beings with the standing that comes from inalienable rights. Each and every life is self-willed and sovereign; each life can only be lived in a body. Not an object to be broken down for parts: a living body. Child sexual abuse is especially designed to turn the body into a cage. The bars may start as terror and pain but they will harden to self-loathing. Instilling shame is the best method to ensure compliance: we are ashamed—sexual violation is very good at that—and for the rest of our lives we will comply. Our compliance is, of course, his control. His power is his pleasure, and another generation of girls will grow up in bodies they will surely hate, to be women who comply.

_______

What has been done to our bodies has been done to our planet. The sadist exerts his control; the necrophiliac turns the living into the dead. The self-willed and the wild are their targets and their necrotic project is almost complete.

Taken one by one, the facts are appalling. In my lifetime, the earth has lost half her wildlife. Every day, two hundred species slip into that longest night of extinction. “Ocean” is synonymous with the words abundance and plenty. Fullness is on the list, as well as infinity. And by 2048, the oceans will be empty of fish. Crustaceans are experiencing “complete reproductive failure.” In plain terms, their babies are dying. Plankton are also disappearing. Maybe plankton are too small and green for anyone to care about, but know this: two out of three animal breaths are made possible by the oxygen plankton produce. If the oceans go down, we go down with them.

How could it be otherwise? See the pattern, not just the facts. There were so many bison on the Great Plains, you could sit and watch for days as a herd thundered by. In the central valley of California, the flocks of waterbirds were so thick they blocked out the sun. One-quarter of Indiana was a wetland, lush with life and the promise of more. Now it’s a desert of corn. Where I live in the pacific northwest, ten million fish have been reduced to ten thousand. People would hear them coming for a whole day. This is not a story: there are people alive who remember it. And I have never once heard the sound that water makes when forty million years of persistence finds it way home. Am I allowed to use the word “apocalypse” yet?

The necrophiliac insists we are mechanical components, that rivers are an engineering project, and genes can be sliced up and arranged at whim. He believes we are all machines, despite the obvious: a machine can be taken apart and put back together. A living being can’t. May I add: neither can a living planet.

Understand where the war against the world began. In seven places around the globe, humans took up the activity called agriculture. In very brute terms, you take a piece of land, you clear every living thing off it, and then you plant it to human use. Instead of sharing that land with the other million creatures who need to live there, you’re only growing humans on it. It’s biotic cleansing. The human population grows to huge numbers; everyone else is driven into extinction.

Agriculture creates a way of life called civilization. Civilization means people living in cities. What that means is: they need more than the land can give. Food, water, energy have to come from someplace else. It doesn’t matter what lovely, peaceful values people hold in their hearts. The society is dependent on imperialism and genocide. Because no one willing gives up their land, their water, their trees. But since the city has used up its own, it has to go out and get those from somewhere else. That’s the last 10,000 years in a few sentences.

The end of every civilization is written into the beginning. Agriculture destroys the world. That’s not agriculture on a bad day. That’s what agriculture is. You pull down the forest, you plow up the prairie, you drain the wetland. Especially, you destroy the soil. Civilizations last between 800 and maybe 2,000 years—they last until the soil gives out.

What could be more sadistic then control of entire continents? He turns mountains into rubble, and rivers must do as they are told. The basic unit of life is violated with genetic engineering. The basic unit of matter as well, to make bombs that kill millions. This is his passion, turning the living into the dead. It’s not just individual deaths and not even the deaths of species. The process of life itself is now under assault and it is losing badly. Vertebrate evolution has long since come to a halt—there isn’t enough habitat left. There are areas in China where there are no flowering plants. Why? Because the pollinators are all dead. That’s five hundred million years of evolution: gone.

He wants it all dead. That’s his biggest thrill and the only way he can control it. According to him it was never alive. There is no self-willed community, no truly wild land. It’s all inanimate components he can arrange to this liking, a garden he can manage. Never mind that every land so managed has been lessened into desert. The essential integrity of life has been breached, and now he claims it never existed. He can do whatever he wants. And no one stops him.

__________

Can we stop him?

I say yes, but then I have no intention of giving up. The facts as they stand are unbearable, but it’s only in facing them that pattern comes clear. Civilization is based on drawdown. It props itself up with imperialism, conquering its neighbors and stripping their land, but eventually even the colonies wear out. Fossil fuel has been an accelerant, as has capitalism, but the underlying problem is much bigger than either. Civilization requires agriculture, and agriculture is a war against the living world. Whatever good was in the culture before, ten thousand years of that war has turned it necrotic.

But what humans do they can stop doing. Granted every institution is headed in the wrong direction, there’s no material reason the destruction must continue. The reason is political: the sadist is rewarded, and rewarded well. Most leftists and environmentalists see that. What they don’t see is the central insight of radical feminism: his pleasure in domination.

The real brilliance of patriarchy is right here: it doesn’t just naturalize oppression, it sexualizes acts of oppression. It eroticizes domination and subordination and then institutionalizes them into masculinity and femininity. Men become real men by breaking boundaries—the sexual boundaries of women and children, the cultural and political boundaries of indigenous people, the biological boundaries of rivers and forests, the genetic boundaries of other species, and the physical boundaries of the atom itself. The sadist is rewarded with money and power, but he also gets a sexual thrill from dominating. And the end of the world is a mass circle jerk of autoerotic asphyxiation.

The real brilliance of feminism is that we figured that out.

What has to happen to save our planet is simple: stop the war. If we just get out of the way, life will return because life wants to live. The forests and prairies will find their way back. Every dam will fail, every cement channel, and the rivers will ease their sorrows and meet the ocean again. The fish will know what to do. In being eaten, they feed the forest, which protects the rivers, which makes a home for more salmon. This is not the death of destruction but the death of participation that makes the world whole.

Sometimes there are facts that require all the courage we have in our hearts. Here is one. Carbon has breached 400 ppm. For life to continue, that carbon needs to get back into the ground. And so we come to grasses.

Where the world is wet, trees make forests. Where it’s dry, the grasses grow. Grasslands endure extreme heat in summer and vicious cold in winter. Grasses survive by keeping 80 percent of their bodies underground, in the form of roots. Those roots are crucial to the community of life. They provide physical channels for rain to enter the soil. They can reach down fifteen feet and bring up minerals from the rocks below, minerals that every living creature needs. They can build soil at an extraordinary rate. The base material they use to make soil is carbon. Which means the grasses are our only hope to get that carbon out of the sky.

And they will do it if we let them. If we could repair 75 percent of the world’s grasslands—destroyed by the war of agriculture—in under fifteen years, the grasses would sequester all the carbon that’s been released since the beginning of the industrial age. Read that again if you need to. Then take it with you wherever you go. Tell it to anyone who will listen. There is still a chance.

The grasses can’t do it alone. No creature exists independent of all others. Repairing the grasslands means restoring the ruminants. In the hot, dry summer, life goes dormant on the surface of the soil. It’s the ruminants who keep the nutrient cycle moving. They carry an ecosystem inside themselves, especially the bacteria that digests cellulose. When a bison grazes, she’s not actually eating the grass. She’s feeding it to her bacteria. The bacteria eat the grass and then she eats the bacteria. Her wastes then water and fertilize the grasses. And the circle is complete.

The grasslands have been eradicated for agriculture, to grow cereal grains for people. Because I want to restore the grasses, I get accused of wanting to kill six billion people. That’s not a random number. In 1800, at the beginning of the Industrial Age, there were one billion people. Now there are seven billion. Six billion are only here because of fossil fuel. Eating a non-renewable resource was never a plan with a future. Yet pointing that out somehow makes me a mass murderer.

Start with the obvious. Nothing we do at these numbers is sustainable. Ninety-eight percent of the old-growth forests and 99 percent of the grasslands are gone, and gone with them was most of the soil they built. There’s nothing left to take. The planet has been skinned alive.

Add to that: all civilizations end in collapse. All of them. How could it be otherwise if your way of life relies on destroying the place you live? The soil is gone and the oil is running out. By avoiding the facts, we are ensuring it will end in the worst possible way.

We can do better than mass starvation, failed states, ethnic strife, misogyny, petty warlords, and the dystopian scenarios that collapse brings. It’s very simple: reproduce at less than replacement numbers. The problem will take care of itself. And now we come to the girls.

What drops the birthrate universally is raising the status of women. Very specifically, the action with the greatest impact is teaching a girl to read. When women and girls have even that tiny bit of power over their lives, they choose to have fewer children. Yes, women need birth control, but what we really need is liberty. Around the world, women have very little control over how men use our bodies. Close to half of all pregnancies are unplanned or unwanted. Pregnancy is the second leading cause of death for girls age 15-19. Not much has changed since Emmeline Pankhurst refused to give up.

We should be defending the human rights of girls because girls matter. As it turns out, the basic rights of girls are crucial to the survival of the planet.

Can we stop him?

Yes, but only if we understand what we’re up against.

He wants the world dead. Anything alive must be replaced by something mechanical. He prefers gears, pistons, circuits to soft animal bodies, even his own. He hopes to upload himself into a computer some day.

He wants the world dead. He enjoys making it submit. He’s erected giant cities where once were forests. Concrete and asphalt tame the unruly.

He wants the world dead. Anything female must be punished, permanently. The younger they are, the sooner they break. So he starts early.

A war against your body is a war against your life. If he can get us to fight the war for him, we’ll never be free. But we said every woman’s body was sacred. And we meant it, too. Every creature has her own physical integrity, an inviolable whole. It’s a whole too complex to understand, even as we live inside it. I had no idea why my eyes were swelling and my lungs were aching. The complexities of keeping me alive could never be left to me.

One teaspoon of soil contains a million living creatures. One tiny scoop of life and it’s already more complex than we could ever understand. And he thinks he can manage oceans?

We’re going to have to match his contempt with our courage. We’re going to have to match his brute power with our fierce and fragile dreams. And we’re going to have to match his bottomless sadism with a determination that will not bend and will not break and will not stop.

And if we can’t do it for ourselves, we have to do it for the girls.

Whatever you love, it is under assault. Love is a verb. May that love call us to action.

Lierre Keith is the author of six books. Visit her website at www.lierrekeith.com

Editor’s note: This essay first appeared August 8, 2015 on RadFem Repost.