by DGR News Service | Sep 15, 2020 | Climate Change, Mining & Drilling, The Problem: Civilization

This is the fourth part in the series. In the previous essays, we have explored the need for a collapse, the relationship between a Dyson sphere and overcomsumption, and our blind pursuit for ‘progress.’ In this piece, Elisabeth describes how the Dyson sphere is an extension of the drive for so-called “green energy.”

By Elisabeth Robson

Techno-utopians imagine the human population on Earth can be saved from collapse using energy collected with a Dyson Sphere–a vast solar array surrounding the sun and funneling energy back to Earth–to build and power space ships. In these ships, we’ll leave the polluted and devastated Earth behind to venture into space and populate the solar system. Such a fantasy is outlined in “Deforestation and world population sustainability: a quantitative analysis” and is a story worthy of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. It says, in so many words: we’ve trashed this planet, so let’s go find another one.

In their report, Mauro Bologna and Gerardo Aquino present a model that shows, with continued population growth and deforestation at current rates, we have a less than 10% chance of avoiding catastrophic collapse of civilization within the next few decades. Some argue that a deliberate and well-managed collapse would be better than the alternatives. Bologna and Aquino present two potential solutions to this situation. One is to develop the Dyson Sphere technology we can use to escape the bonds of our home planet and populate the solar system. The other is to change the way we (that is, those of us living in industrial and consumer society) live on this planet into a ‘cultural society’, one not driven primarily by economy and consumption, in order to sustain the population here on Earth.

The authors acknowledge that the idea of using a Dyson Sphere to provide all the energy we need to populate the solar system is unrealistic, especially in the timeframe to avoid collapse that’s demonstrated by their own work. They suggest that any attempt to develop such technology, whether to “live in extraterrestrial space or develop any other way to sustain population of the planet” will take too long given current rates of deforestation. As Salonika describes in an earlier article in this series, “A Dyson Sphere will not stop collapse“, any attempt to create such a fantastical technology would only increase the exploitation of the environment.

Technology makes things worse

The authors rightly acknowledge this point, noting that “higher technological level leads to growing population and higher forest consumption.” Attempts to develop the more advanced technology humanity believes is required to prevent collapse will simply speed up the timeframe to collapse. However, the authors then contradict themselves and veer back into fantasy land when they suggest that higher technological levels can enable “more effective use of resources” and can therefore lead, in principle, to “technological solutions to prevent the ecological collapse of the planet.”

Techno-utopians often fail to notice that we have the population we do on Earth precisely because we have used technology to increase the effectiveness (and efficiency) of fossil fuels and other resources* (forests, metals, minerals, water, land, fish, etc.). Each time we increase ‘effective use’ of these resources by developing new technology, the result is an increase in resource use that drives an increase in population and development, along with the pollution and ecocide that accompanies that development. The agricultural ‘green revolution’ is a perfect example of this: advances in technology enabled new high-yield cereals as well as new fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, irrigation, and mechanization, all of which prevented widespread famine, but also contributed to an ongoing explosion in population, development, chemical use, deforestation, land degradation and salinization, water pollution, top soil loss, and biodiversity loss around the world.

As economist William Stanley Jevons predicted in 1865, increasing energy efficiency with advances in technology leads to more energy use. Extrapolating from his well-proved prediction, it should be obvious that new technology will not prevent ecological collapse; in fact, such technology is much more likely to exacerbate it.

This mistaken belief that new technology can save us from collapse pervades the policies and projects of governments around the world.

Projects like the Green New Deal, the Democrat Party’s recently published climate plan, and the UN’s sustainable development goals and IPCC recommendations. All these projects advocate for global development and adoption of ‘clean technology’ and ‘clean industry’ (I’m not sure what those terms mean, myself); ’emissions-free’ energy technologies like solar, wind, nuclear and hydropower; and climate change mitigation technologies like carbon capture and storage, smart grids, artificial intelligence, and geo-engineering. They tout massive growth in renewable energy production from wind and solar, and boast about how efficient and inexpensive these technologies have become, implying that all will be well if we just keep innovating new technologies on our well worn path of progress.

Miles and miles of solar panels, twinkling like artificial lakes in the middle of deserts and fields; row upon row of wind turbines, huge white metal beasts turning wind into electricity, and mountain tops and prairies into wasteland; massive concrete dams choking rivers to death to store what we used to call water, now mere embodied energy stored to create electrons when we need them–the techno-utopians claim these so-called clean’ technologies can replace the black gold of our present fantasies–fossil fuels–and save us from ourselves with futuristic electric fantasies instead.

All these visions are equally implausible in their capacity to save us from collapse.

And while solar panels, wind turbines, and dams are real, in the sense that they exist–unlike the Dyson Sphere–all equally embody the utter failure of imagination we humans seem unable to transcend. Some will scoff at my dismissal of these electric visions, and say that imagining and inventing new technologies is the pinnacle of human achievement. With such framing, the techno-utopians have convinced themselves that creating new technologies to solve the problems of old technologies is progress. This time it will be different, they promise.

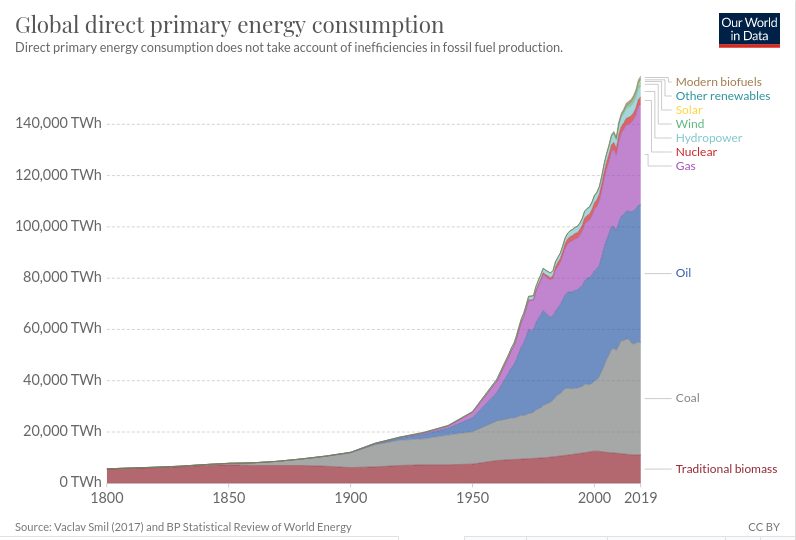

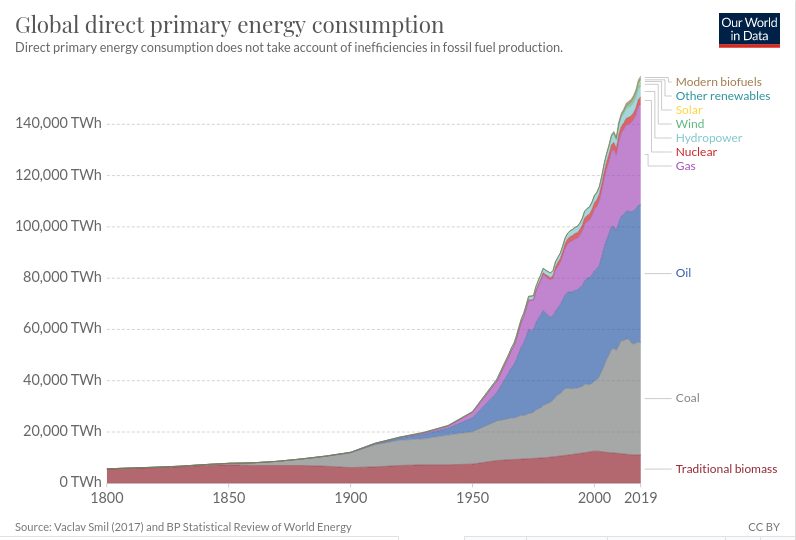

And yet if you look at the graph of global primary energy consumption:

it should be obvious to any sensible person that new, so-called ‘clean’ energy-producing technologies are only adding to that upward curve of the graph, and are not replacing fossil fuels in any meaningful way. Previous research has shown that “total national [US] energy use from non-fossil-fuel sources displaced less than one-quarter of a unit of fossil-fuel energy use and, focussing specifically on electricity, each unit of electricity generated by non-fossil-fuel sources displaced less than one-tenth of a unit of fossil-fuel-generated electricity.”

In part, this is due to the fossil fuel energy required to mine, refine, manufacture, install, maintain, and properly dispose of materials used to make renewable and climate mitigation technologies. Mining is the most destructive human activity on the planet, and a recent University of Queensland study found that mining the minerals and metals required for renewable energy technology could threaten biodiversity more than climate change. However, those who use the word “clean” to describe these technologies conveniently forget to mention these problems.

Wind turbines and solar arrays are getting so cheap; they are being built to reduce the cost of the energy required to frack gas: thus, the black snake eats its own tail. “Solar panels are starting to die, leaving behind toxic trash”, a recent headline blares, above an article that makes no suggestion that perhaps it’s time to cut back a little on energy use. Because they cannot be recycled, most wind turbine blades end up in landfill, where they will contaminate the soil and ground water long after humanity is a distant memory. Forests in the southeast and northwest of the United States are being decimated for high-tech biomass production because of a loophole in EU carbon budget policy that counts biomass as renewable and emissions free. Dams have killed the rivers in the US Pacific Northwest, and salmon populations are collapsing as a result. I could go on.

The lies we tell ourselves

Just like the Dyson Sphere, these and other technologies we fantasize will save our way of life from collapse are delusions on a grand scale. The governor of my own US state of Washington boasts about how this state’s abundant “clean” hydropower energy will help us create a “clean” economy, while at the same time he fusses about the imminent extinction of the salmon-dependent Southern Resident Orca whales. I wonder: does he not see the contradiction, or is he willfully blind to his own hypocrisy?

The face of the Earth is a record of human sins (1), a ledger written in concrete and steel; the Earth twisted into skyscrapers and bridges, plows and combines, solar panels and wind turbines, mines and missing mountains; with ink made from chemical waste and nuclear contamination, plastic and the dead bodies of trees. The skies, too, tell our most recent story. Once source of inspiration and mythic tales, in the skies we now see airplanes and contrails, space junk and satellites we might once have mistaken for shooting stars, but can no longer because there are so many; with vision obscured by layers of too much PM2.5 and CO2 and NOx and SO2 and ozone and benzene. In the dreams of techno-utopians, we see space ships leaving a rotting, smoking Earth behind.

One of many tales of our Earthly sins is deforestation.

As the saying goes, forests precede us, and deserts follow; Mauro Bologna and Gerardo Aquino chose a good metric for understanding and measuring our time left on Earth. Without forests, there is no rain and the middles of continents become deserts. It is said the Middle East, a vast area we now think of as primarily desert, used to be covered in forests so thick and vast the sunlight never touched the ground (2). Without forests, there is no home for species we’ve long since forgotten we are connected to in that web of life we imagine ourselves separate from, looking down from above as techno-gods on that dirty, inconvenient thing we call nature, protected by our bubble of plastic and steel. Without forests, there is no life.

One part of one sentence in the middle of the report gives away man’s original sin: it is when the authors write, “our model does not specify the technological mechanism by which the successful trajectories are able to find an alternative to forests and avoid collapse“. Do they fail to understand that there is no alternative to forests? That no amount of technology, no matter how advanced–no Dyson Sphere; no deserts full of solar panels; no denuded mountain ridges lined with wind turbines; no dam, no matter how wide or high; no amount of chemicals injected into the atmosphere to reflect the sun–will ever serve as an “alternative to forests”? Or are they willfully blind to this fundamental fact of this once fecund and now dying planet that is our only home?

A different vision

I’d like to give the authors the benefit of the doubt, as they end their report with a tantalizing reference to another way of being for humans, when they write, “we suggest that only civilisations capable of a switch from an economical society to a sort of ‘cultural’ society in a timely manner, may survive.” They do not expand on this idea at all. As physicists, perhaps the authors didn’t feel like they had the freedom to do so in a prestigious journal like Nature, where, one presumes, scientists are expected to stay firmly in their own lanes.

Having clearly made their case that civilized humanity can expect a change of life circumstance fairly soon, perhaps they felt it best to leave to others the responsibility and imagination for this vision. Such a vision will require not just remembering who we are: bi-pedal apes utterly dependent on the natural world for our existence. It will require a deep listening to the forests, the rivers, the sky, the rain, the salmon, the frogs, the birds… in short, to all the pulsing, breathing, flowing, speaking communities we live among but ignore in our rush to cover the world with our innovations in new technology.

Paul Kingsnorth wrote: “Spiritual teachers throughout history have all taught that the divine is reached through simplicity, humility, and self-denial: through the negation of the ego and respect for life. To put it mildly, these are not qualities that our culture encourages. But that doesn’t mean they are antiquated; only that we have forgotten why they matter.”

New technologies, real or imagined, and the profits they bring is what our culture reveres.

Building dams, solar arrays, and wind turbines; experimenting with machines to capture CO2 from the air and inject SO2 into the troposphere to reflect the sun; imagining Dyson Spheres powering spaceships carrying humanity to new frontiers–these efforts are all exciting; they appeal to our sense of adventure, and align perfectly with a culture of progress that demands always more. But such pursuits destroy our souls along with the living Earth just a little bit more with each new technology we invent.

This constant push for progress through the development of new technologies and new ways of generating energy is the opposite of simplicity, humility, and self-denial. So, the question becomes: how can we remember the pleasures of a simple, humble, spare life? How can we rewrite our stories to create a cultural society based on those values instead? We have little time left to find an answer.

* I dislike the word resources to refer to the natural world; I’m using it here because it’s a handy word, and it’s how most techno-utopians refer to mountains, rivers, rocks, forests, and life in general.

(1) Susan Griffin, Woman and Nature

(2) Derrick Jensen, Deep Green Resistance

In the final part of this series, we will discuss what the cultural shift (as described by the authors) would look like.

Featured image: e-waste in Bangalore, India at a “recycling” facility. Photo by Victor Grigas, CC BY SA 3.0.

by DGR News Service | Aug 31, 2020 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change

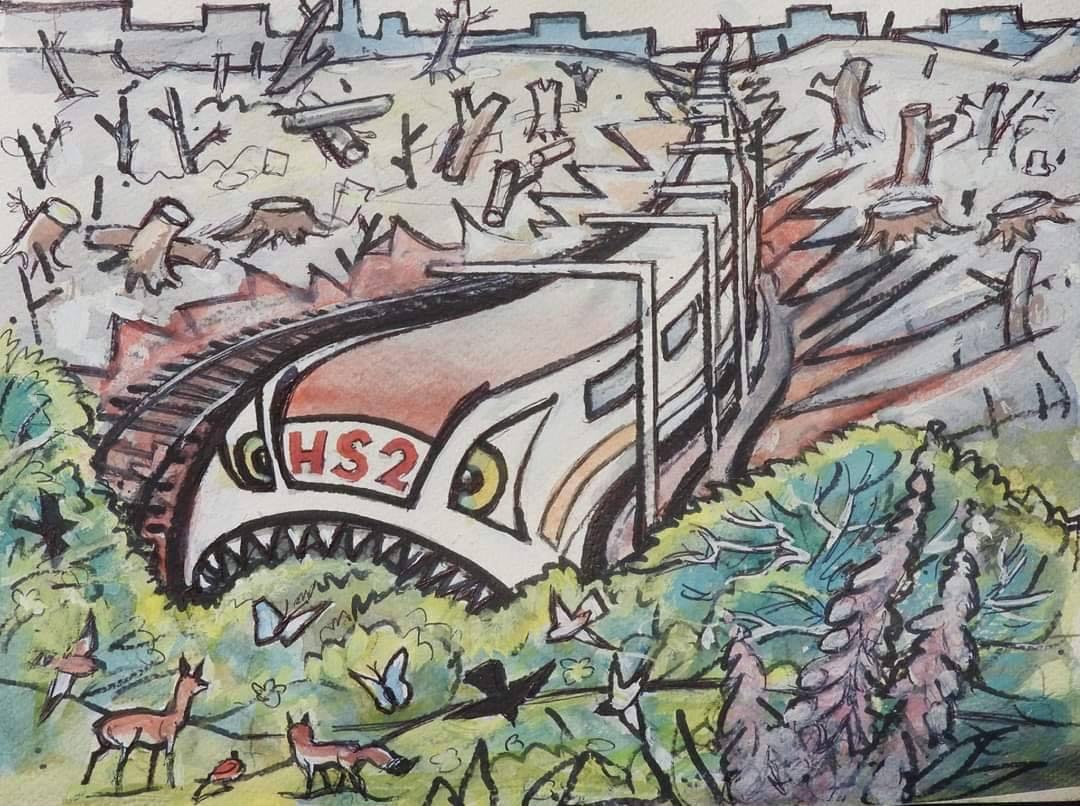

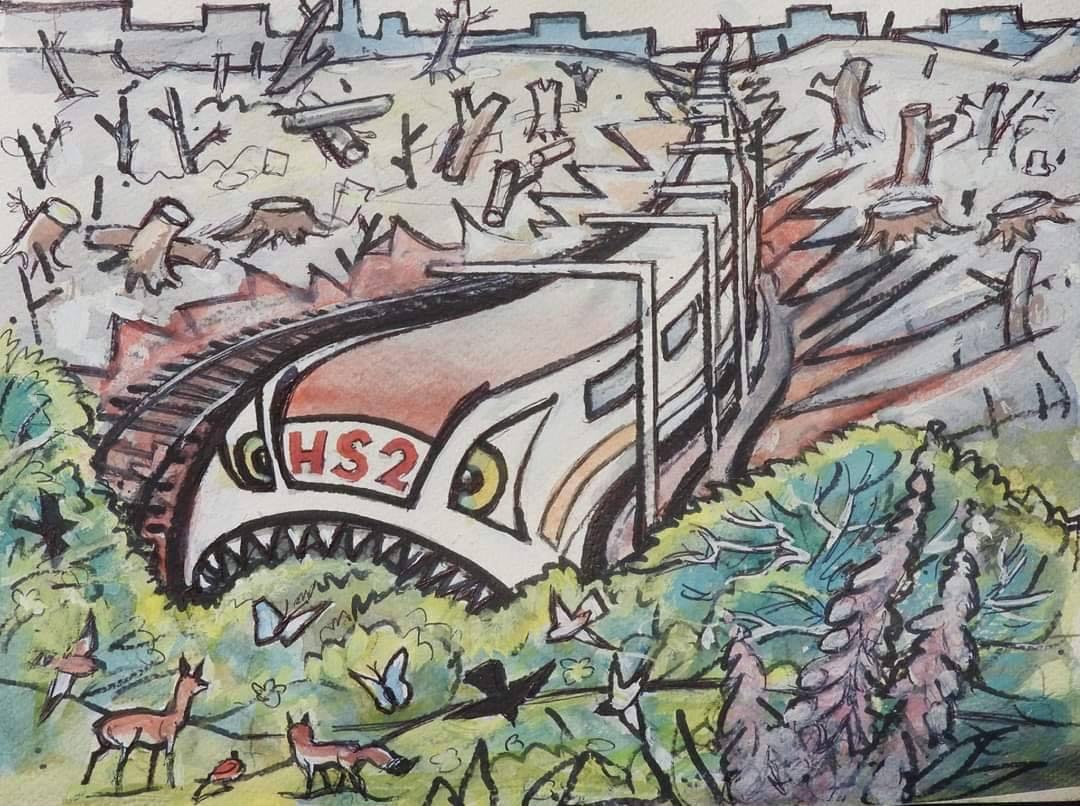

In this writing Ben asks questions about a rail development that is destroying the natural world. He asks what it would take to stop the development and why we are not all talking about it.

Is high speed rail the pinnacle of civilisations’ insanity?

By Ben Warner

Probably not, unfortunately, but it is an excellent example. Standing in the same place for centuries should mean something. The men must have made a mistake. They have destroyed a National Asset. The National Heritage has a list of criteria for granting protected status that includes being in the same place for centuries. Why have they just demolished a possible candidate for the National Heritage List for England? The answer is, it was a tree who was razed to the ground and not a building. The tree was in the way of “progress” and those who get in the way are often crushed.<

Imagine a country so insane it would spend £100 billion during a pandemic and one of the worst recessions in human history, just to speed up a journey by 20 minutes. That’s 5 billion a minute. Imagine the same project would destroy over 700 wildlife sites including sites designated by that same culture as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSI) and not be carbon ‘friendly’ for at least a hundred years.

Imagine it would simultaneously threaten the water supply of its biggest city and use between 6 and 10 million liters of water during its construction. Now imagine the same project has been made obsolete by a virus that has stopped people travelling for business. Of course you do not have to imagine it. The country is the UK and it is as insane as the culture it is part of Industrial civilisation.

High Speed Rail (HS2)

The first stage of HS2 will make the rail journey from the UK’s London to Birmingham 1200 seconds quicker. That is for people who can afford the tickets, which are likely to be in the region of £50. What are people going to do with these 20 minutes? If they were commuting there is probably little they can do at work that they could not have done on the train.

The rational arguments for HS2 do not exist. There are none. But the project will continue. Why? Because it has already started, too much money has been spent and too much embarrassment will be caused, if it stopped. For a culture that prides itself on its rationality, this is baffling. Even when the evidence is so strong, it is hard to accept that our own culture is insane.

Right now there are brave people occupying woods and sleeping in tree houses attempting to slow down the HS2 project and the pointless destruction it is causing. Their efforts are courageous and valuable. Their resistance probably won’t stop HS2, but their actions will not be in vain because the morality of what they are doing is clear for all beings who care to learn about it.

What would it take to stop HS2?

The people in the camps are above ground and peaceful. But what if there was another, completely separate, group of militant underground activists using the hit and run tactics of successful resistance groups? Would sabotage stop HS2? Would sand or water or bleach in the engines of their destructive machines stop them? Would constant, relentless physical intimidation of the workers make the project impossible to complete?

What would a truly effective campaign look like and why are we not talking about it?

Ben Warner is a longtime guardian with DGR, a teacher, and an activist.

Featured image artist unknown via Stop HS2 campaign. There are suggestions of how you can help resist the destruction on their website: stophs2.org.

by DGR News Service | Aug 28, 2020 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change

Godwin Vasanth Bosco reports on extreme precipitation that has fallen on the Nilgiri plateau of southern India the last few years. These extreme and unprecedented rain events have led to massive landslides and other ecological damage. Little has been done to address the crisis.

Featured image: A massive landslide in one of the largest sholas in the Avalanche region of the Nilgiris, with hundreds of native trees and the stream ecology washed away.

Crumbling Ancient Mountain Ecology

Written and photographed by Godwin Vasanth Bosco / Down to Earth

Thousands of trees lay dead and strewn around the western parts of the Nilgiri Plateau in southern India.

Deep gashes scar ancient mountains slopes, standing a stark contrast to the lush green vegetation that they otherwise support. As conservationists, activists, and concerned people in various parts of India are fighting to protect forests and wilderness areas from being deforested, mined, and diverted to `developmental’ projects, there is another level of destruction that is happening to our last remaining wild spaces. Climate change is causing the widespread collapse of ecosystems.

Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have just hit record-breaking levels of 417 ppm in May 2020. It has never been so high in the last 3 million years. Along with global warming caused sea-level rise and the melting of polar ice caps and glaciers, the steep increase in greenhouse gas concentrations has led to a surge in the frequency of extreme climate events. A region of the earth where climate change caused weather extremities are exceedingly apparent are the coastal plains and the Western Ghats regions of southern India. In the last four years, this region has been affected by eight tropical cyclones and consecutive extreme rainfall events during the southwest monsoon periods of the last two years.

These bouts of intense storms have been interspersed with periods of severe droughts, heatwaves, deficient, and failed monsoons.

On August 8, 2019, the Avalanche and Emerald valley regions, which are part of the Kundha watershed, received an unprecedented amount of over 900 mm [2.9 feet] of rainfall in 24 hours.

It broke the record for the highest rainfall ever recorded in Tamil Nadu, by nearly twice the amount. Over four days, this region experienced close to 2500 mm [8.2 feet] of rainfall. To put this in perspective, the nearest city (100 km east) in the plains of Tamil Nadu, Coimbatore, receives around 600 mm of rain annually. The Kundha watershed bore a deluge that was four times the annual rainfall amount, over just four days.

The upper watershed of the Kundha River is a complex of several peaks above 2400 meters and broad deep valleys. The Kundha River, which is a primary tributary to the Bhavani that feeds into the Cauvery, is fed by numerous streams and rivulets at the headwater sections.

With the barraging downpour, nearly every stream and rivulet burst its course. Vast tracts of precious soil and shola ecology slipped away on either side of the watercourses. Gone are the rich black soil layers topped with spongy humus that line the streams; washed away are dark moss and wild balsam covered rocks that shaped the flow of every stream; lost are the thousands of shola trees, dwarf bamboo and forest kurinji that guarded the streams, saplings, ferns and orchids of the forest floor. In place of these are deep cuts of gauged out the earth, revealing the red underlying lateritic soil layers, and lightly shaded freshly exposed rocks.

Numerous large landslides have occurred on intact grassland slopes too.

Uprooted and washed away trees, and dead Rhododendron arboreum ssp nilagiricum trees in a broad valley near the Avalanche region.

Native shola trees and stream ecology completely washed away on either side of tributaries of the Kundha River

Shola-grassland mosaic in danger

The cloud forest ecology, known as sholas, is specialized in growing along the folds and valleys of these mountains. They are old-growth vegetation and harbour several endemic and rare species of flora and fauna. These naturally confined forests are already some of the most endangered forest types, because of habitat loss and destruction.

The recent episode of extreme precipitation caused landslides, have dealt a telling blow on these last remaining forest tracts. What is even more shocking is that montane grassland stretches have also experienced large landslides.

The montane grasslands occur over larger portions of the mountains here, covering all the other areas that sholas do not grow in. Together, the shola-grassland mosaic is the most adept at absorbing high rainfall amounts and releasing it slowly throughout the year, giving rise to perennial streams. Over a year they can experience an upwards of 2500 to 5500 mm of rainfall, which is intricately sequestered by complex hydrological anatomy that carefully lets down most of this water, using what is needed to support the ecology upstream.

The native tussock grasses especially are highly adapted to hold the soil strongly together on steep slopes. However, even this ecology is now giving way under pressure from extreme weather events. The shola-grassland mosaic ecology cannot withstand the tremendously high amounts of rainfall (over 2400 mm) that occur in significantly short periods (over 4 days). Worsening climate change is driving the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, resulting in a level of ecosystem collapse, never witnessed before.

An example of intact shola-grassland mosaic in the hills of the Nilgiri plateau, with the sholas growing in valleys and grasslands covering the slopes.

In the southwest monsoon season of 2018, similar events of unusually high rainfall occurred over the highland districts of Idukki, Wayanad, and Coorg, causing hundreds of landslides. A predominant view was that this was primarily because of the indiscriminate construction of roads and proliferating concretization of the hills.

However, even within the highly stable shola-grassland ecology, a large number of landslides have occurred in spots with no apparent forms of disturbance such as roads and pathways cut through them. This signifies that climate-change has reached a level that is beyond the capacity of the ecosystem and land resilience.

What is causing the collapse of the last remaining wild spaces is the culmination of every action that has contributed to the climate crisis.

These actions invariably stem from places that have long lost their plant ecological cover—urban-industrial-agricultural complex. There is fatally no time to keep ignoring this primary cause. Even if we ignore this and look to safeguard the last remain wilderness areas from being deforested or `developed’, they are vulnerable to climate change-related destruction.

Threats closer to the last remaining ecological spaces must be also curtailed. For instance, despite the consecutive years of extreme precipitation over short periods, in the Nilgiri Biosphere region, there are hardly any steps being taken to address ecological security. Building regulations stand to get eased and road expansion works continue in full swing.

However, worryingly similar to what happened in the last two years when much of the annual rainfall was concentrated over a few days later in the monsoon period, this year too, 2020 has be no different. The onset of the monsoon was delayed, and large parts of peninsula experienced a significant deficiency well into the monsoon period. This year’s monsoon has brought intense, short bursts of extreme rainfall, not only in the Western Ghats regions and southern India, but all across the Indian subcontinent.

Destruction by dams and tunnels

Neela-Kurinji or Strobilanthes kunthiana flowering in the grassland habitats of the Nilgiris. This spectacle takes place only once in 12 years

The Kundha watershed region can be broadly divided into two sections – the higher slopes and the descending valleys. Hundreds of landslides occurred in both these sections, with shola-grassland ecology dominating in the higher slopes, and various types of land-uses such as tea cultivation, vegetable farming, villages and non-native tree plantations dominating the descending valleys. The descending valleys are also studded with several dams and hydroelectric structures.

The Kundha Hydro-Electric Power Scheme is one of the largest hydropower generating installations in Tamil Nadu-with 10 dams, several kilometers of underground tunnels, and a capacity of 585 MW. In addition to this, this system is now getting two more dams and a series of tunnels, to set up large pumped storage hydropower facilities. The claim is to generate 1500 MW, of electricity during peak demand hours, but while using almost 1800 MW in the process.

With the level of destruction that extreme precipitation events are bringing to the Kundha watershed, it is disastrous to add more large dams and tunnels. The intensity of floods has turned so strong that even the largest dam complexes in the world, face threats of being breached.

An Aerides ringens orchid growing on a shola tree.

Safeguarding the last remaining zones of ecology and biodiversity from threats of direct destruction is crucial. Concurrently, the larger world-wide urban-industrial-agricultural complex, from where the climate crisis stems from needs drastic change. The constant incursions into more and more ecological spaces in the form of new dams, roads, and buildings, are also connected to this complex.

Whether it is the landslides in the grasslands of the high elevation plateaus in southern India; the melting glaciers of the Himalayas in northern India; the dying coral and rising sea levels elsewhere in the planet; the global coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic that has brought about unimaginable changes – we have to understand the interconnectedness of these dire effects and learn from nature.

Godwin Vasanth Bosco is an ecologist working to restore shola and grassland ecology in the Nilgiri Biosphere. He is the author of the book Voice of a Sentient Highland on the Nilgiri Biosphere.

This piece was first published on Down to Earth. All the photographs were taken by the author himself.

by DGR News Service | Aug 20, 2020 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, Climate Change

This is the first in a series of articles reflecting on a recent study which predicts collapse of industrial society within a few decades. By destroying the ecological foundation on which all life depends, civilization makes collapse inevitable. Max Wilbert describes the destruction caused by the industrial civilization, and what we can do for a just transition to a more sustainable way of life.

by Max Wilbert

A new study published in Scientific Reports finds that there is a 90% chance of civilization collapsing irreversibly within the next 20 to 40 years.

The report, published on May 6th by Dr. Gerardo Aquino, a research associate at the Alan Turing Institute in London, and Professor Mauro Bologna of the Depratment of Electronic Engineering at the University of Tarapacá in Chile, uses statistical and logistical modeling to look at destruction of the planet, and specifically focuses on deforestation and population growth.

By plugging in statistics and trends in resource consumption and running thousands of model-runs with different assumptions, Aquio and Bologna predict the most likely course of future human society.

The researchers conclude that civilization has a “very low probability, less than 10% in the optimistic estimate, to survive without facing a catastrophic collapse.”

This should not be a surprise. The form of social organization we call civilization (a way of life based on the growth of cities) began around 10,000 years ago, and since then this form of society has reduced the number of trees around the world by at least 46 percent—and those who do remain are, on average, much smaller and younger. At current rates of deforestation, nearly every tree on the planet will be gone within the next 100-200 years.

On top of this, civilization (and it’s modern form, industrial civilization) is causing a global mass extinction event, changing the composition of the atmosphere and instigating global climate change, polluting the highest mountains and deepest ocean trenches with industrial chemicals and plastics, desertifying and eroding vast portions of the planet’s soils via agriculture, and fragmenting and shattering what habitat does remain intact via networks of roads and urbanization.

Most people perceive collapse as a terrible thing, and indeed a global collapse will result in a great deal of suffering, disease, and death. But the reality is, a vast amount of suffering is happening now, caused by the continued functioning of industrial civilization. A full forty percent of all human deaths are caused by air, water, and soil pollution according to Cornell research. The CoViD-19 pandemic is a direct result of civilization and the destruction of forests.

On top of this, collapse at this point may be inevitable. As the book Deep Green Resistance explains, “We are in overshoot as a species. A significant portion of the people now alive may have to die before we are back under carrying capacity, and that disparity is growing. Every day carrying capacity is driven down by hundreds of thousands of humans, and every day the human population increases by more than 200,000. The people added to the overshoot each day are needless, pointless deaths. Delaying collapse, they argue, is itself a form of mass murder.”

If you are concerned about this, as I am, as we all should be, you should be working to relocalize food production and smooth the transition away from industrial agriculture. Collapse has both positive aspects (declines in pollution, reduction in logging, end of international shipping, reduction in energy consumption, etc.) and negative aspects (collapse of social structures, medical systems, increased demands on local forests, etc.). These need to be managed and prepared for.

In the long-term, collapse will benefit both humans and nature by stopping industrial civilization and its pollution, global warming, desertification, and so on. Another physicist, Tim Garrett from the University of Utah, has conducted research into global warming and concluded that “only complete economic collapse will prevent runaway global climate change.”

There are over 400 oceanic dead zones created by fertilizer and nutrient runoff from industrial farms. Only one has recovered: the dead zone in the Black Sea, which healed after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the crash of industrial farming in the area. The area is now home to healthy wildlife and fish populations which support a stronger local economy.

Ultimately, our health and success as human beings is inseparable from the health of the planet. To destroy the Earth for temporary enrichment a slow form of suicide. But deeper than that, it is matricide, patricide, fratricide. It is the murder of one’s own family. We will only thrive when the natural world, our kin, are thriving as well. Human beings are not doomed to destroy the planet. We can live in other ways, and indeed, that is our only hope.

Featured image by the author.

Our next piece will discuss how a Dyson sphere (one of the proposed “solutions” in the original article) will not save us from a collapse.

by DGR News Service | Aug 8, 2020 | Climate Change, Human Supremacy, The Problem: Civilization

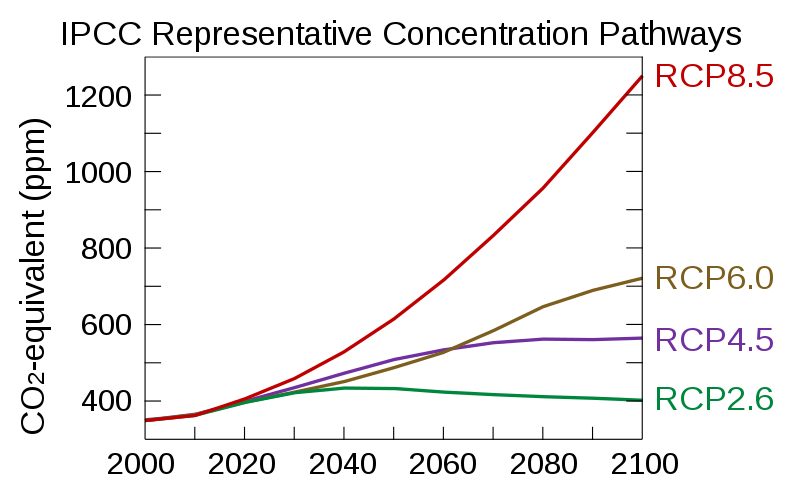

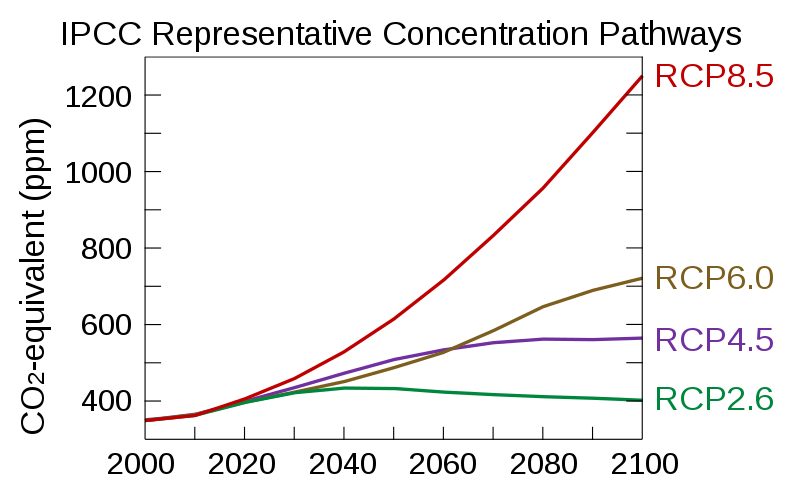

This article, originally posted by the Woods Hole Research Centre on August 3rd 2020, states that the “Worst case” for CO2 emissions scenario is actually the best match for assessing the climate risk, impact by 2050.

The RCP 8.5 CO2 emissions pathway, long considered a “worst case scenario” by the international science community, is the most appropriate for conducting assessments of climate change impacts by 2050, according to a new article published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The work was authored by Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC) Risk Program Director Dr. Christopher Schwalm, Dr. Spencer Glendon, a Senior Fellow at WHRC and founder of Probable Futures, and by WHRC President Dr. Philip Duffy.

Long dismissed as alarmist or misleading, the paper argues that is actually the closest approximation of both historical emissions and anticipated outcomes of current global climate policies, tracking within 1% of actual emissions. “Not only are the emissions consistent with RCP 8.5 in close agreement with historical total cumulative CO2 emissions (within 1%), but RCP8.5 is also the best match out to mid-century under current and stated policies with still highly plausible levels of CO2 emissions in 2100,” the authors wrote. “…Not using RCP8.5 to describe the previous 15 years assumes a level of mitigation that did not occur, thereby skewing subsequent assessments by lessening the severity of warming and associated physical climate risk.”

Four scenarios known as Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) were developed in 2005 for the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Report (AR5). The RCP scenarios are used in global climate models, and include historical greenhouse gas emissions until 2005, and projected emissions subsequently. RCP 8.5 assumes the greatest fossil fuel use, and a resulting additional 8.5 watts per square meter of radiative forcing by 2100. The commentary also emphasizes that while there are signs of progress on bending the global emissions curve and that our emissions picture may change significantly by 2100, focusing on the unknowable, distant future may distort the current debate on these issues. “For purposes of informing societal decisions, shorter time horizons are highly relevant, and it is important to have scenarios which are useful on those horizons. Looking at mid-century and sooner, RCP8.5 is clearly the most useful choice,” they wrote.The article also notes that RCP 8.5 would not be significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, adding that “we note that the usefulness of RCP 8.5 is not changed due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Assuming pandemic restrictions remain in place until the end of 2020 would entail a reduction in emissions of -4.7 Gt CO2. This represents less than 1% of total cumulative CO2 emissions since 2005 for all RCPs and observations.”

“Given the agreement of 2005-2020 historical and RCP8.5 total CO2 emissions and the congruence between current policies and RCP8.5 emission levels to mid-century, RCP8.5 has continued utility, both as an instrument to explore mean outcomes as well as risk,” they concluded. “Indeed, if RCP8.5 did not exist, we’d have to create it.”

You can access the original article here:

https://whrc.org/worst-case-co2-emissions-scenario-is-best-match-for-assessing-climate-risk-impact-by-2050/

Featured image: Efbrazil / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

by DGR News Service | Jul 23, 2020 | Climate Change

Siberian heat drives Arctic ice extent to record low for early July

by Gloria Dickie / Mongabay

- On June 17, 2020, a Siberian town registered a temperature of 100 degrees Fahrenheit, the highest ever recorded above the Arctic Circle. High temps across the region are driving impacts of great concern to scientists, firefighters, and those who maintain vulnerable Arctic infrastructure, including pipelines, roads, and buildings.

- The Siberian heat flowed over the adjacent Arctic Ocean where it triggered record early sea ice melt in the Laptev Sea, and record low Arctic sea ice extent for this time of year. While 2020 is well positioned to set a new low extent record over 2012, variations in summer weather could change that.

- The heat has also triggered wildfires in Siberia, releasing 59 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in June and drying out the region’s tundra. Some blazes are known as “zombie fires” possibly having smoldered underground all winter between 2019 and 2020.

- Also at risk from the rapid rise in warmth is civil and military infrastructure, built atop thawing permafrost. As Siberia heated up this year, a fuel tank at a Russian power plant collapsed, leaking 21,000 tons of diesel into the Ambarnaya and Dadylkan rivers, a major Arctic disaster. Worse could come as the world continues warming.

The record-setting heat wave that swept through Arctic Siberia in June has yielded a wide-range of deleterious effects in the expansive polar and sub-polar region, triggering raging wildfires, thawing permafrost, and now, spurring the rapid melt-out of Arctic sea ice.

Last month, Siberian temperatures spiked, reaching a record average more than 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees Fahrenheit) hotter than normal, according to recently released data from the European Union. The remote town of Verkhoyansk in northeast Siberia recorded a reading of more than 38 degrees Celsius (100 degrees Fahrenheit) on June 17, the highest temperature ever recorded north of the Arctic Circle.

Under this metaphorical blow torch, ice extent in the seas that border Siberia has plummeted in recent days, pushing the Arctic region as a whole into the record books. Between July 2 and July 7, sea ice extent across the Arctic Ocean went from being at its fifth lowest extent for this time of year since satellite record-keeping began in 1979, melting into first place, slightly below even the calamitous year of 2012 which eventually saw sea ice hit a record low at the end of the summer melt season in September.

As of July 9, sea ice extent in the global Arctic sits at just 8.310 million square kilometers (3.2 million square miles). If that melting momentum carries forward (and nobody knows if it will), 2020 could nab the title of the lowest ice extent year come September — with unknown long-term ramifications for the Arctic and the global climate.

An exceedingly abnormal spring and early summer in Siberia is thought to be largely responsible for 2020’s sudden surge downward. “The ice is opening up quite quickly and dramatically. It’s now at a record low in the Laptev Sea off northern Siberia,” says Walt Meier, a senior research scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC).

Published by

Gloria Dickie on 10 July 2020. You can read the full article and images here: