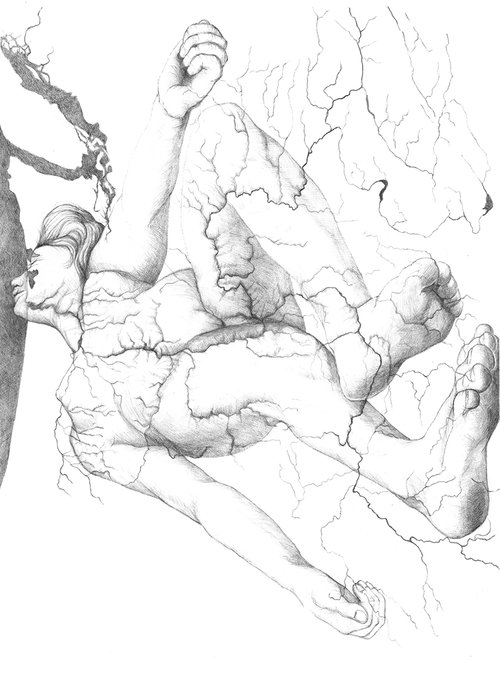

This is an edited transcript of this Deep Green episode. Featured image: “Watershed” by Nell Parker.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about aquifers.

As we know, this culture is drawing down aquifers around the world. Aquifers are underground rivers, lakes, seeps – it’s underground water and they can be anywhere from just six inches below the surface down to about 10,000 feet and they are being drawn down around the world.

We’ve heard of the Ogallala aquifer – it’s is an absolutely huge aquifer that has been used for irrigation for the last hundred years – it’s being drawn down terribly. Aquifers can recharge but it’s very slow. The other thing that’s happening to aquifers around the world is that they’re being poisoned – sometimes unintentionally as people pollute the ground and it leaches down into the groundwater and sometimes intentionally as in fracking or fracking for geothermal. The latter are “green”; where they put chemicals down and then explode the rocks into a billion pieces so they can frack out the oil or they can then allow the heated water to escape to the surface which they use to generate electricity. When you poison an aquifer – if recharging an aquifer takes a long, long, long, long, long time – detoxifying an aquifer takes that same amount of time, longer. I don’t even know how long it takes before an aquifer would become detoxified. It’s all a very, very, very stupid idea.

I’ve said many times that my environmentalism – I love the natural world, I love bears, I love salmon and I love trees – but my environmentalism also emerges from a fundamental conservatism, that I think it’s really, really, stupid to create a mess that you can’t fix. You know, if you drive salmon extinct that’s a mess you can’t fix because you can’t bring them back, and if you toxify an aquifer you’ve created a mess that you can’t fix. This is something I learned very young from my mom. If you make a mess you clean it up and if you cannot clean up that mess you don’t make it in the first place.

None of that is the point on why I want to bring this up. There are a lot of studies that have been done about who lives in these aquifers. They make up about 40% of the microbial habitat on the planet and account for I think 20% of the microbial population on the planet – viruses, archaea, bacteria and also fungi down to maybe a hundred feet; fungi don’t go much lower in the aquifer. Without bacteria we would all die almost instantly. Bacteria do the real work of life on this planet.

There have been a fair number of studies done on who lives down there;

and I have seen a fair number of people express concern over the drawdown of aquifers; and this concern is always expressed in terms of if “we keep drawing it down we can’t draw down more”. “If we empty the Ogallala aquifer how are we going to irrigate?” It’s always self-centered. The same with toxification; “if we toxify this water then when we put in a well our water is going to catch on fire or we won’t be able to drink the water.”

They may exist but I have yet to see one person, one person, in the entire world express concern for the aquifer communities as communities themselves. That person may exist but I’ve never heard of them and if that person does care about those communities as communities, as biomes – I mean there are people who say “gosh I love the grasslands” and “I wish the grasslands were there because I love buffalo and I love buffalo for their own sake”; “I love beavers for their own sake”; “I love old growth forests for their own sake.” I’ve never heard anybody say the Ogallala aquifer should not be drained because it is a biome, a community, of its own and has the right to exist for its own sake without us drawing it down and without us toxifying it. If anybody does care about them and works on these issues, I would love to interview you; but this is not an ad for that. I want to raise the issue.

It took me years of thinking about aquifers before it occurred to me that they’re their own communities

and now I’m the only person I know who thinks about this – that when they’re drawn out that’s harming those communities. I want for that to start to become part of the public conversation about aquifers – that not only do aquifers provide water for us and for everybody else; not only do aquifers provide hugely – here’s one thing, when an aquifer collapses the soil subsides above it and I just read an article a few days ago about how that that causes tremendous harm to infrastructure; it’s like and..? AND..? And how about the ecological infrastructure? How about the communities who live down there? How about the surface native communities? I want to make it part of the public conversation that aquifers exist for their own sake. They have their own beingness and their own communities and those communities are just as important to them as your community is to you and my community is to me.

Great perspective. Actually I am only commenting because I want to read the other comments 🙂

Aquifers in at least 20 countries are on the verge of collapse, including those in the world’s top 3 grain producers — the U.S., China, and India.

The Ogallala (extending from Nebraska to Texas) is the world’s largest aquifer. And its overuse has already forced agriculture to be drastically reduced in the southern part of the Texas panhandle. The constant lowering of the water table has caused the ground level above the Ogallala to drop more than 10 feet since the 1930s.

Land above parts of California’s Central Valley has subsided even more, and in far less time. This is due in part to almond farming, which puts a huge demand on water. Drive through some of these almond growing areas in mid-summer, and you’ll see orchards in 2 inches of standing water, as it rapidly evaporates in 100° heat. Almond farming in California has expanded by close to 1000% since the 1960s, and it isn’t because Californians are addicted to almonds. The growth is largely driven by absentee profiteers, utterly indifferent to the fact that they are now producing over 80% of the world’s almonds in a notoriously dry region. Cattle ranching — also driven by overseas markets — is another major contributor to groundwater loss, which is likewise driven by greed. At this rate, the aquifer will soon be dry, and half of the state that currently produces most of America’s vegetables will, in effect, become semi-desert or desert.

The situation is even worse in Arizona, where owners have leased or sold much of the land to Saudi investors. Because Saudi Arabia idiotically began growing and even exporting wheat and alfalfa in the 1960s, the Saudi aquifer was completely drained in 50 years. So now Arizona’s aquifer is beinf destroyed, too, simply to feed the camels and horses of a corrupt desert monarchy, halfway around the world.

You might ask why the government of Arizona hasn’t put a stop to this. And the answer would explain all you need to know about the insanity of capitalism. Though the Arizona aquifer is expected to run dry by around 2030, the state hasn’t stepped in because Arizona’s politicians and landowners would rather make profits today than have any agriculture at all, 10 years from now.

The same mentality is racing toward bankruptcy and starvation all over the world, with the possible exceptions of a handful of small nations (Bhutan, Suriname, Norway, Switzerland, and New Zealand pretty much cover it) who take conservation and the future somewhat seriously.

I grew up wondering what would happen when the world ran out of industrial resources like oil, gold, and steel. And while those are on pace to be effectively exhausted in this century, as well, I could not have imagined that the resources most likely to bring about the collapse of civilization are fresh water, topsoil, and sand. (Desert sand lacks the binding qualities of ocean and riverbed sand, so the planet’s beaches and estuaries are rapidly being destroyed for the sake of more pavement, new skyscrapers, land expansion in places like Singapore and the Persian Gulf, and China’s recent fetish for “island building.”)

Around 270 years ago, population growth and the Industrial Revolution forced us to begin relying on fossil fuels. That spurred the massive growth of cities, while industrial agriculture and the conquest of childhood diseases brought about a sharp decline in infant mortality. And now we’ve painted ourselves into a corner. Common sense demands that we live in balance with nature. But there are too many of us to live without industry, which demands that nature be replaced by dams, factories, farms, landfills, and toxic dumps.

Technological advances have given people in half of the world luxuries and conveniences that were unknown to kings, 2 centuries ago. And a 1000% population increase since 1750 has made us dependent on industry for food and water. We’re now so addicted to texhnology, we have become deluded into believing it will somehow solve all the problems it has caused. And because capitalism’s profit motive demands perpetual growth, we’re too blinded by hubris even to see that constant growth on a finite planet is suicide.

And so we lie to ourselves. “Surely science will think of something,” we say. But we’re listening to the wrong scientists. We embrace the good news, and dismiss the bad. We listen to techies like Elon Musk, who believe in myths like “green energy,” mining the asteroids, and living on Mars. We go on congratulating ourselves for having babies, while science tells us that much of our current population will die in misery, as rivers and aquifers run dry, the tropics become unlivable, forests become farms, farms become deserts, and coastlines are swallowed up by acidified oceans, full of plastic instead of fish.

Civilization is all about profit. This year’s financial statements are infinitely more important to business than a future decade’s viability. And politicians are concerned with the next election cycle, not the next generation of voters.

We’re like those periodic generations of lemmings and locusts, that outrun their food supplies, and die en masse. The only differnce is that we know better, but do it anyway. And when we die, we take the world down with us.

Growing alfalfa for cattle uses far more water than growing almonds. But neither should be grown in an arid or semi-arid climate, which are the only two climates that exist in the Valley, and California shouldn’t be destroying the Valley and the Delta to grow food for people outside of California. (For those who don’t know, California’s San Joaquin valley was largely a seasonal marshland teeming with elk and other wildlife before the colonizers got here. It’s now totally ruined with agriculture, from killing the native plants & animals for agriculture to sucking the Delta dry to poisoning everything with pesticides, the latter so badly that people are warned to keep their windows up and the air conditioner on “recirculate” when the drive there.) As usual, cattle are the big problem. Beef is by far the most environmentally and ecologically harmful food you can eat.

Am I to understand you dont know by heart Wes Jacksons New Roots for Agriculture in which his 1970’s book warns us about the drawing down of the aquifers?

Well, among other things I’m a deep ecologist, which means that I strongly feel and I think that all life has a right to exist FOR ITS OWN SAKE. Human concerns about things like whether well water — which BTW only exists due to human overpopulation — is poisoned are minor details compared to the lives of the aquifers themselves and everyone living there. (I’m trying to stop calling nonhumans “things,” it’s a disgusting and immoral way to talk or think about them.)

So while Derrick has never heard me talk about caring about aquifers for their own sake, that in fact is the only reason that I care about them.

The company here is great, I look forward to more conversation. Yes, an aquifer deserves to continue for its own sake. It’s just one of those things we’re not “allowed” to talk about.

You deleted my critique of your narcissism when I quoted you saying: “…now I’m the only person I know who thinks about this – that when they’re drawn out that’s harming those communities.” This is not factual; indeed, many have thought this.

Not able to accept the criticism, eh? I have heard first-hand accounts of your pride; it’s too bad because we need people in this movement who play well with others.

Derrick is not a narcissist and he is working very well with so many people. We are able to accept critisism but in a polite and factual way. I don’t know what you want, but if you continue agitating we will continue blocking your comments.

“We are able to accept critisism(sic) but in a polite and factual way.”

No movement, especially movements that require solidarity, can survive attitudes such as “…now I’m the only person I know who thinks about this…” when discussing obvious facts that entire schools of science are aware of. This applies to almost all knowledge, and most diligent college students learn early on “If you think you have an original idea, then go do some research.”

It has been well-known since the past century that soil and water are entire ecosystems unto themselves, just as all living creatures are ecosystems unto themselves; the whole world is teeming with microbes and creatures who have lived on earth in their own unique way: yes, it is a great pity to destroy the ecosystem of the aquifers.