Editor’s note: Deep-sea mining is a sign of addiction. Only a culture driven by a death urge masquerading as a profit-production-motive could contemplate destroying some of the largest and most intact remaining habitats on Earth and call it “green.” One of the first companies that may begin deep sea mining is The Metals Company, headquartered in Vancouver, Canada. TMC plans to extract nickel, cobalt, copper, and manganese from “polymetallic nodules” dredged from the deep seafloor in an area of international waters called the Clarion Clipperton Zone southwest of San Diego. The company claims that mining the oceans is less harmful to the environment. Nothing could be further from the truth.

As a biocentric organization, Deep Green Resistance is opposed to deep-sea mining — and indeed, all industrial mining. Mining is the one of the most destructive industries on the planet in terms of habitat destruction, pollution, and social injustice. Modern industrial civilization is fully dependent on mining, and as an organization dedicated to dismantling industrial civilization, we oppose and will fight all industrial mining activities. We put the planet first.

by Elizabeth Claire Alberts / Mongabay

- This week, the International Seabed Authority, the intergovernmental body tasked with overseeing deep-sea mining in international waters, concluded its recent set of meetings, which ran from July 4 to Aug. 4, 2022.

- The purpose of these meetings was to progress with negotiations of mining regulations, with a view that deep-sea mining will start in July 2023 after the Pacific island nation of Nauru triggered a rule that could obligate this to happen.

- While many countries appear to support the rapid development of these regulations, an increasing number of other countries have expressed concern with this deadline, indicating a possible turn of events.

It starts with tiny deep-sea fragments — shark’s teeth or slivers of shell. Then, in a process thought to span millions of years, they get coated in layers of liquidized metal, eventually becoming solid, lumpy rocks that resemble burnt potatoes. These formations, known as polymetallic nodules, have caught the attention of international mining companies because of what they harbor: rich deposits of commercially sought-after minerals like cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese — the very metals that go into the batteries for renewable technologies like electric cars, wind turbines, and solar panels.

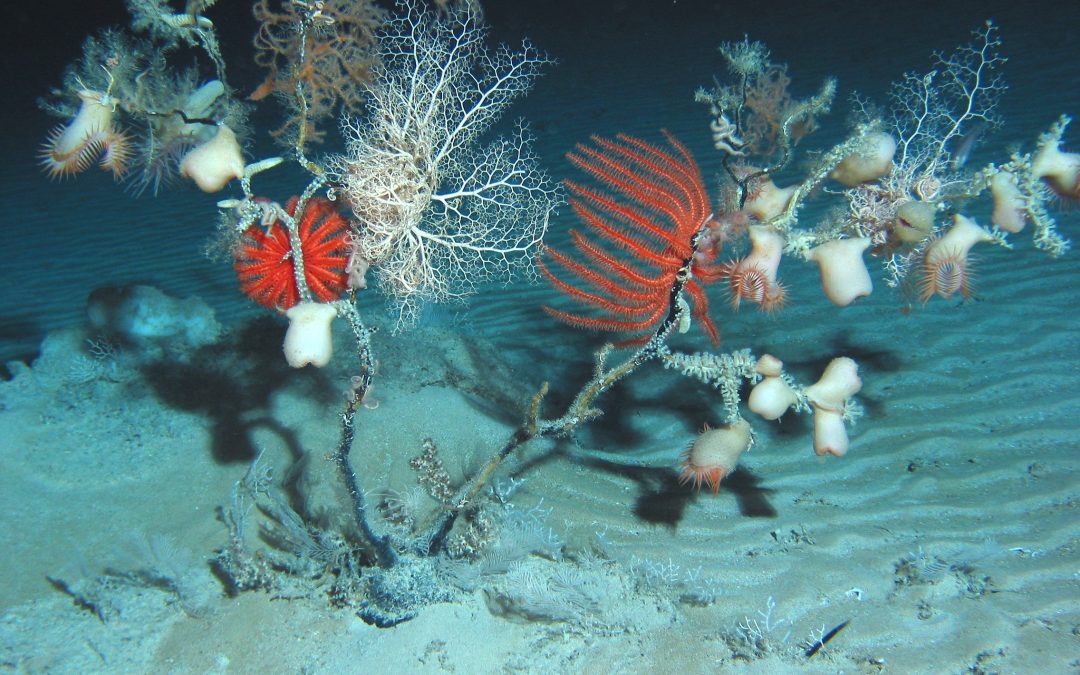

But while some experts say we must mine the deep sea to combat climate change, others warn against it, saying we know too little about the damage that seabed mining would cause to the ocean’s life-sustaining properties.

Actual extraction has yet to begin, but in June 2021, the small Pacific island country of Nauru pushed the world closer to this possibility by notifying the International Seabed Authority — the intergovernmental body that oversees mining in international waters — that it had triggered a two-year rule in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This rule would theoretically allow it to start mining in June 2023 under whatever mining rules are in place by then. Nauru itself doesn’t have a mining company with this interest, but it sponsors a subsidiary of Canada-based and U.S.-listed The Metals Company.

Since then, the ISA has been working to negotiate a set of regulations that would allow it to follow the two-year rule. But at the latest set of meetings that took place between July 4 and Aug. 4 in Kingston, Jamaica, progress on the mining code appears to have stalled, observers reported.

“Overall, the feeling in the room is that there’s now a majority of states that are recognizing that it’s unrealistic, unachievable, and would be highly irresponsible,” Emma Wilson, a conservation expert who attended the recent ISA meetings as a representative of the NGO OceanCare, told Mongabay.

Representatives from several countries, including Spain, Chile, New Zealand, Ecuador, Costa Rica, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Trinidad and Tobago, made the case that the mining regulations shouldn’t be rushed to meet the obligations of the two-year rule. Spain’s representative, for instance, said that “as a precaution, the time has come to take a break,” while Costa Rica’s representative said “because we are responsible for the Common Heritage of Humankind, for our peoples and for future generations, we must act with caution.” (The UNCLOS defines the seabed and its resources as “the common heritage of mankind.”)

However, other countries, such Australia, the U.K., Tonga, and Nauru itself, took the position that regulations should be approved without delay. Tonga’s representative said the nation stood “ready to support work of Authority and relevant bodies especially for completion of regulatory frameworks in [a] timely fashion while assuring due diligence where appropriate.” Even France stated that it was committed to adopting “a legal framework with rigorous environmental protections to ensure that harm to ecosystems in the marine environment is minimized.” This position seemed to be in contrast to President Emmanuel Macron’s statement at the U.N. Ocean Conference in Lisbon at the end of June that “we have to create the legal framework to stop high seas mining and not to allow new activities that endanger ecosystems.”

On July 25, Chile’s delegation presented a letter to the ISA Secretariat, requesting that a discussion about the two-year rule become an agenda item at the assembly portion of the meetings, which began on Aug. 1. But this request was ignored, OceanCare’s Wilson said. Instead, the ISA Secretariat relegated it to the end of the meeting in the “any other business” category, which “undermined it,” and the ISA Secretariat even closed the meetings a day early, she added.

“One thing that became very, very evident this week is that the ISA Secretariat is doing everything that it can to brush the conversation under the carpet about [whether] there is another possibility of not adopting the regulation,” Wilson said.

Mongabay previously reported on concerns about transparency at the recently concluded ISA meetings, including accusations that the ISA had restricted access to key information and hampered interactions between member states and civil society.

Despite the many setbacks, Matt Gianni, a political and policy adviser for the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition (DSCC), told Mongabay that he was observing a change happening in the negotiations.

“There’s a broad recognition that unless something really surprising happens, these regulations are not only unlikely to be adopted by July 2023, but they’re probably not likely to be adopted for several years at least,” said Gianni, who attended the meetings as a representative of EarthWorks, an NGO that works to shield communities and the environment from the negative impacts of extractive activities.

Gianni added that the ISA council has also yet to agree upon the financial mechanisms under which mining could operate, which need to be put into place, in addition to the regulations, before the ISA can issue exploitation licenses. However, he said it’s still unclear whether deep-sea mining will officially be stalled.

“It’s a bit like the Titanic,” Gianni said. “We’re starting to see the rivets popping and the thing is slowly starting to turn. But is it going to miss the iceberg and head in the direction of protecting the marine environment? That’s still an open question.”

Elizabeth Claire Alberts is a staff writer for Mongabay. Follow her on Twitter @ECAlberts.

It’s still shocking to me that deep sea mining is considered at all, yet not without precedent. Brazil allows the destruction of the Amazon. The Soviets drained the Aral Sea. “Settlers” in what is today the US hunted rival predetors like wolves to near extinction (which is yet another reason why I don’t see anything in my European colonist heritage worth being proud of). Civilization, especially in its industrial form, seems to always desecrate the rest of nature and kill or subjugate anyone in their way. Deep sea mining will inevitably continue that pattern if allowed to occur anywhere.

“…lumpy rocks that resemble burnt potatoes.” THERE’S an idea! We could burn potatoes, and call it “renewable energy”!

As for mining anywhere, they’re lying to us. Last year, I went to a couple of steel industry websites, looked up “annual consumption” and “estimated global reserves,” and divided the latter by the former. The quotient indicated that we’d run out of steel in about 60 years.

Just one problem: The industry’s figures on “annual consumption” are nowhere near annual production averages for the last 50 years. Using those real world numbers, civilization will exhaust its ability to produce steel in 2036.

So, either our perpetual growth economy has hidden plans to shrink by 75%, beginning now, or the industrial world grinds to a halt before today’s toddlers finish high school.

That’s how organized industrial civilization is: Tell “consumers” there’s nothing to worry about, and hope they’re too stupid to do the arithmetic!

Around 1980, I read a chemical industry memo that said that since we’ve destroyed the Earth, we need to start mining asteroids. That was around 40 years ago, so they must feel more strongly about this now.

The human misconception that we can just continue consuming the Earth indefinitely causes humans to continue this kind of behavior. Obviously, at some point everything will be used up. Then what? This is a perfect example of why I say that our battle is for hearts & minds, not a physical or legal battle (though sometimes the latter must also be fought to combat immediate problems). Nothing lasts forever, but the Earth should be able to exist and thrive for another 4.5 billion years or so until the sun starts to burn out. Neither the Earth, its ecosystems, its habitats, nor the life here, should be brought to a premature death because of the wrongful lifestyles, actions, and behaviors of humans.

While I agree that cultivating new ecologically sound ideological and spiritual paths is an important component of puttingvour species back on the right path, the physical and legal battles are simply the most pressing now. If we don’t fight back now, less of the planet and ecosystems will remain when civilization colkapses under its own weight and the wrath of Gaia. I envision cultivating spirituality as part of the “home front”. It’s purpose should be to prepare our species for the coming chaos and motivate them to fight ti protect the Earth and stop injustice.

Cultivating and expanding ecologically sound spirituality and battling for hearts and minds are only a small part of whst needs to be done. The role of cultivating spirituality should currently be focused on preparing people for the coming upheaval and motivating them to fight to protect the Earth and stop injustice. If we win the physical and legal battles then there will be more lrft when civilization collapses under its own weight and the weath of Gaia, the natural disasters it helped create.

Hmm, now my old comment posts

Great news we should support as much warming as possible so mining companies can mine more areas. have the mning companies thought about what happens ad islands go under water they probably have. Below is an except about this possibility. This could lead to even more dangers to the ocean. Excerpt begins* The effects of sea-level rise on islands themselves are widely recognized, but the effects on the islands’ sea areas have received surprisingly little attention, perhaps because the impact is not readily visible. In addition to their land area, islands have territorial seas and continental shelves, and they can also have exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and contiguous zones. These EEZs and continental shelves in some cases cover huge areas of the sea. In the case of islands belonging to a coastal state, the state has sovereign rights to the natural resources of these sea areas; a sea-level rise, by causing a change in the baselines for measurement of the sea areas in question, can have a major impact on the extent of the state’s claims. And if the rise causes an island to submerge below the surface of the water, the baselines will cease to exist; this will raise the new issue of the legal status of the sea areas that the state has claimed. In the worst-case scenario, an entire island state might end up submerged under the rising waters or so extensively flooded that it becomes uninhabitable or incapable of sustaining its own economic life; such a development would raise the serious issues of the legal status of not only the sea areas it claimed but also the island state itself. The effects of sea-level rise on islands themselves are widely recognized, but the effects on the islands’ sea areas have received surprisingly little attention, perhaps because the impact is not readily visible. In addition to their land area, islands have territorial seas and continental shelves, and they can also have exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and contiguous zones. These EEZs and continental shelves in some cases cover huge areas of the sea. In the case of islands belonging to a coastal state, the state has sovereign rights to the natural resources of these sea areas; a sea-level rise, by causing a change in the baselines for measurement of the sea areas in question, can have a major impact on the extent of the state’s claims. And if the rise causes an island to submerge below the surface of the water, the baselines will cease to exist; this will raise the new issue of the legal status of the sea areas that the state has claimed. In the worst-case scenario, an entire island state might end up submerged under the rising waters or so extensively flooded that it becomes uninhabitable or incapable of sustaining its own economic life; such a development would raise the serious issues of the legal status of not only the sea areas it claimed but also the island state itself. Islands’ Sea Areas: Effects of a Rising Sea Level

HAYASHI Moritaka. https://www.spf.org/https://www.spf.org/