Featured image: Simon Eeman / shutterstock

by Anna Pigott, Swansea University / The Conversation

The latest Living Planet report from the WWF makes for grim reading: a 60% decline in wild animal populations since 1970, collapsing ecosystems, and a distinct possibility that the human species will not be far behind. The report repeatedly stresses that humanity’s consumption is to blame for this mass extinction, and journalists have been quick to amplify the message. The Guardian headline reads “Humanity has wiped out 60% of animal populations”, while the BBC runs with “Mass wildlife loss caused by human consumption”. No wonder: in the 148-page report, the word “humanity” appears 14 times, and “consumption” an impressive 54 times.

There is one word, however, that fails to make a single appearance: capitalism. It might seem, when 83% of the world’s freshwater ecosystems are collapsing (another horrifying statistic from the report), that this is no time to quibble over semantics. And yet, as the ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer has written, “finding the words is another step in learning to see”.

Although the WWF report comes close to finding the words by identifying culture, economics, and unsustainable production models as the key problems, it fails to name capitalism as the crucial (and often causal) link between these things. It therefore prevents us from seeing the true nature of the problem. If we don’t name it, we can’t tackle it: it’s like aiming at an invisible target.

Why capitalism?

The WWF report is right to highlight “exploding human consumption”, not population growth, as the main cause of mass extinction, and it goes to great lengths to illustrate the link between levels of consumption and biodiversity loss. But it stops short of pointing out that capitalism is what compels such reckless consumption. Capitalism – particularly in its neoliberal form – is an ideology founded on a principle of endless economic growth driven by consumption, a proposition that is simply impossible.

Industrial agriculture, an activity that the report identifies as the biggest single contributor to species loss, is profoundly shaped by capitalism, not least because only a handful of “commodity” species are deemed to have any value, and because, in the sole pursuit of profit and growth, “externalities” such as pollution and biodiversity loss are ignored. And yet instead of calling the irrationality of capitalism out for the ways in which it renders most of life worthless, the WWF report actually extends a capitalist logic by using terms such as “natural assets” and “ecosystem services” to refer to the living world.

By obscuring capitalism with a term that is merely one of its symptoms – “consumption” – there is also a risk that blame and responsibility for species loss is disproportionately shifted onto individual lifestyle choices, while the larger and more powerful systems and institutions that are compelling individuals to consume are, worryingly, let off the hook.

Who is ‘humanity,’ anyway?

The WWF report chooses “humanity” as its unit of analysis, and this totalising language is eagerly picked up by the press. The Guardian, for example, reports that “the global population is destroying the web of life”. This is grossly misleading. The WWF report itself illustrates that it is far from all of humanity doing the consuming, but it does not go as far as revealing that only a small minority of the human population are causing the vast majority of the damage.

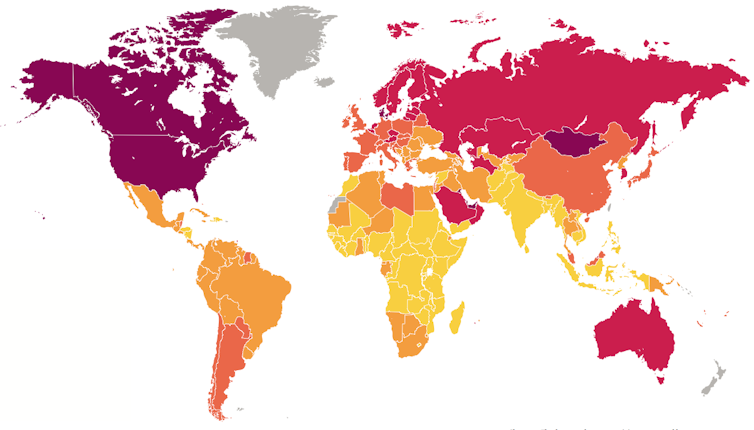

From carbon emissions to ecological footprints, the richest 10% of people are having the greatest impact. Furthermore, there is no recognition that the effects of climate and biodiversity collapse are overwhelming felt by the poorest people first – the very people who are contributing least to the problem. Identifying these inequalities matters because it is this – not “humanity” per se – that is the problem, and because inequality is endemic to, you guessed it, capitalist systems (and particularly their racist and colonial legacies).

The catch-all word “humanity” papers over all of these cracks, preventing us from seeing the situation as it is. It also perpetuates a sense that humans are inherently “bad”, and that it is somehow “in our nature” to consume until there is nothing left. One tweet, posted in response to the WWF publication, retorted that “we are a virus with shoes”, an attitude that hints at growing public apathy.

But what would it mean to redirect such self-loathing towards capitalism? Not only would this be a more accurate target, but it might also empower us to see our humanity as a force for good.

Breaking the story

Words do so much more than simply assign blame to different causes. Words are makers and breakers of the deep stories that we construct about the world, and these stories are especially important for helping us to navigate environmental crises. Using generalised references to “humanity” and “consumption” as drivers of ecological loss is not only inaccurate, it also perpetuates a distorted view of who we are and what we are capable of becoming.

By naming capitalism as a root cause, on the other hand, we identify a particular set of practices and ideas that are by no means permanent nor inherent to the condition of being human. In doing so, we learn to see that things could be otherwise. There is a power to naming something in order to expose it. As the writer and environmentalist Rebecca Solnit puts it:

Calling things by their true names cuts through the lies that excuse, buffer, muddle, disguise, avoid, or encourage inaction, indifference, obliviousness. It’s not all there is to changing the world, but it’s a key step.

The WWF report urges that a “collective voice is crucial if we are to reverse the trend of biodiversity loss”, but a collective voice is useless if it cannot find the right words. As long as we – and influential organisations such as the WWF, in particular – fail to name capitalism as a key cause of mass extinction, we will remain powerless to break its tragic story.![]()

Anna Pigott, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Environmental Humanities, Swansea University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks