by Doug Pollock / Friends of OSU Old Growth

In a recent, eloquent defense of a “no-compromise” approach to protecting our dwindling wild areas, author George Wuerthner quotes Bob Marshall, founder of the Wilderness Society:

“We do not want those whose first impulse is to compromise. We want no straddlers, for, in the past, they have surrendered too much good wilderness and primeval areas which should never have been lost.“

Mr. Wuerthner provides a long list of key conservation victories, including the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), Yellowstone, Grand Teton, and Olympic National Park – all of which were protected because heroic people refused to compromise. He cites notable failures, as well, writing:

“Pragmatists, in the end, leave messes for future generations to clean up. Capitulating to local interests with half-baked compromises in the interest of expediency typically produces uneven results. Either they do not adequately protect the land or create enormous headaches for future conservationists to undue often at a significant political and economic expense.“

The National Forests system was originally set up by President Theodore Roosevelt to protect forests from commercial activity – not log them. Compromises made by Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the Forest Service, resulted in mining companies (and later timber companies) gaining access to our National Forests. In the early 1900’s, almost no one could imagine that the seemingly limitless supply of virgin timber on private lands would one day be exhausted. They could not conceive that in a few generations’ time, timber companies and their partners in government agencies would be fighting tooth and nail to log the dwindling amount of old growth in our national forests – our collective natural heritage.

Lessons for the Elliott Mr. Wuerthner’s impassioned writing has left me wondering what lessons future generations will glean from the current process surrounding the Elliott State Forest (likely to be handed over to OSU with their timber-centric “research design” in the coming weeks). How will they see the unusually short public outreach/comment period and the rush to complete the OSU plan in time for the Land Board’s approval? How will they judge our mainstream environmental groups who seem afraid to openly criticize the egregious shortcomings of the plan and process? Will future Oregonians accept that compromise was the best we could hope for with the Elliott State Forest?

Insight from the Advisory Committee: In a recent email, Bob Sallinger (Portland Audubon member serving on the Advisory Committee) clarified the current situation with OSU’s draft plan for the Elliott:

“The draft plan calls for cutting up to 3287 acres of mature forest (between 65 and 152 years of age) over a period of a couple or two decades using selective harvest (20%-80% retention). Several hundred acres within this 3287 acres are on the younger side (65-100 years old) but the majority is in 100-152 year range…

I don’t think there is anybody in the conservation community that thinks it is a good idea to cut these older stands or that the research benefits outweigh the benefits of preserving 100% of the older stands…Ultimately the question the conservation community will need to decide is whether they can live with the tradeoffs in this plan…

Pretty much 100% of the changes and concessions over the past year have been made to address conservation concerns. Despite that fact, if conservation interests sign-off, it looks like we will have consensus among all stakeholders including tribes, timber, counties, hunters and rec, and schools…

So bottom line is that there are definitely tradeoffs in this plan. There would be under any management scenario. In a perfect world we would lock up the entire Elliott as a carbon/ biodiversity reserve. However the same issues that have necessitated a decades long battle over the Elliott are still in play today.

Folks will have to decide whether the inclusion of things like clearcuts in about 14,000 acres of existing plantations (under 65 years of age) or selective harvest in a limited number of stands >65 are deal breakers or not. In doing so, I would encourage folks to think carefully about the other pathways that are available to us.“

I have great respect for Bob. He has been a true conservation hero on the Advisory Committee. But the 12-member committee was compromised at the outset by the inclusion of hardliners with vested economic interests (Douglas County Commissioner Chris Boice is a great example). When Bob writes about the need to live with tradeoffs and reach consensus among all stakeholders, I wonder what happened to the broader group of stakeholders – the citizens of Oregon. I also wonder why experts in forest ecology and carbon were not included on the committee – while timber interests were.

When it comes to the fate of the Elliott, surveys show Oregonians overwhelmingly support conservation. When I see DSL and the Land Board showing such great deference to OSU, I wonder, “Where’s the deference to Oregonians?” When it comes to this state forest, one ought to defer to the citizens of this state. And when it comes to compromise and tradeoffs, one has only to look at the millions of acres of clearcuts in our state and federal forests to understand that we’ve already compromised our natural heritage.

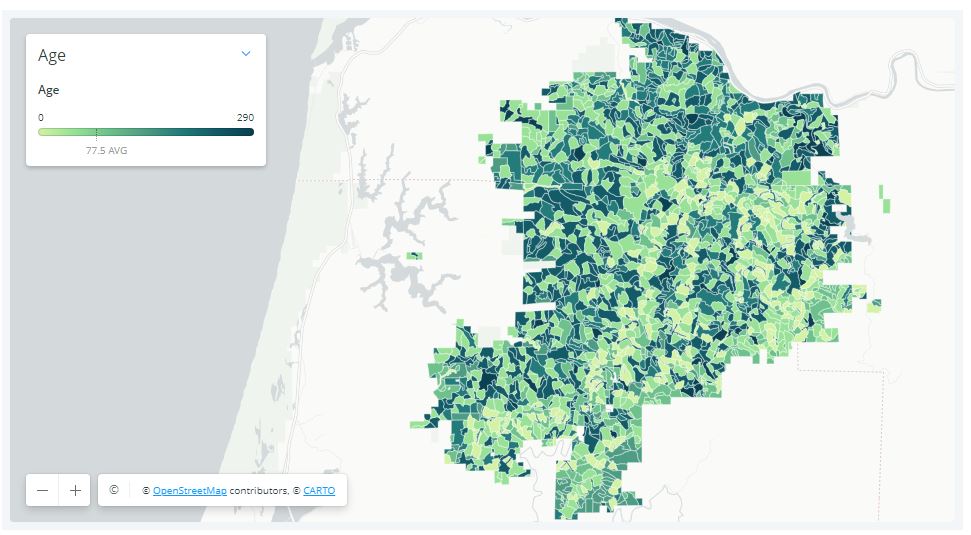

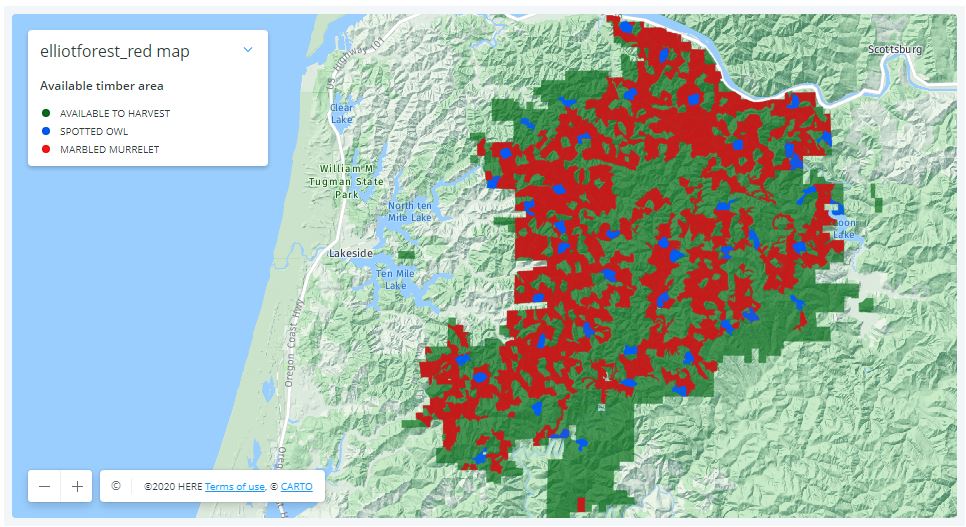

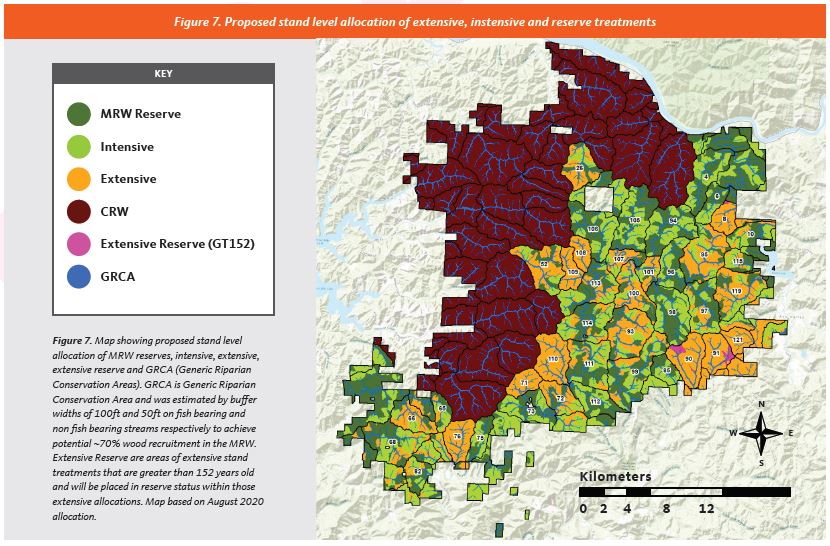

Pictures Tell the Story: OSU’s latest draft plan for the Elliott State Research Forest (ESRF) is an unwieldy mix of contradictions, obfuscation, and technical jargon put together by folks who clearly are not adept at communicating with a broader audience. When it comes to understanding this fundamental issue of compromise in the Elliott, pictures are the key.

The map below shows the locations of older trees (indicated by darker shades of green) in the Elliott State Forest. It is important to note that significant quantities of older trees are scattered across vast stretches of the Forest.

This next map shows the habitat of threatened birds (marbled murrelet in red and northern spotted owls in blue) in the Elliott. Predictably, the habitat is closely aligned with the older stands.

This final map shows how the OSU would divide the forest. The purple areas (denoted as “CRW”) would be “conservation research watersheds”, with limited logging allowed. The dark green areas (labeled as “MRW Reserve”) will be subject to experimental treatments (= logging) in the coming decades. The orange areas (labeled “Extensive”) will undergo thinning in which 20-80% of the trees are to be cut (including thousands of acres of older trees). The light green areas (labeled “Intensive”) are composed of trees less than 65 years of age, and will be subject to clearcutting.

Viewed from the perspective of older trees and habit for our threatened birds, OSU’s plan for the Elliott is a complete disconnect. As the maps clearly show, it would sacrifice a majority of the Forest to continued clearcutting and fragmentation.

George Wuerthner’s eloquent words could not be more applicable to the Elliott:

“In far too many cases, there is a tendency to believe that it is necessary to appease local interests typically by agreeing to weakened protections or resource giveaways to garner the required political support for a successful conservation effort. However, this fails to consider that in nearly all cases where effective protective measures are enacted, it has been done over almost uniform local opposition.

In those instances where local opposition to a conservation measure is mild or does not exist, it probably means the proposal will be ineffective or worse—even set real conservation backward…Nevertheless, many environmentalists now believe that due to regional parochialism and lack of historical context, significant compromises are necessary to win approval for new conservation initiatives.“

The Elliott State Forest has already been heavily compromised – OSU’s plan would perpetuate the mistakes of the past.

Featured image: Lewis and Clark River 2148s.JPG, ©2013 Walter Siegmund, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en.

There’s also some overlap between personality and values. For instance, introverts are more likely to enjoy quiet 7197 hanging around the homestead, whereas extroverts are more apt to want to be out meeting and greeting. Some issues are amenable to finding a middle road, but as it gets more into personality differences, core values, and identity, the tension rises. As the feelings grow that our needs are not getting met and our partner isn’t hearing us, the polarization can get exaggerated. We can even end up even thinking that our person doesn’t care or doesn’t like us! And how do you compromise on that!