In this latest video from Thacker Pass, Max explains why he is protesting against lithium mining for the so called green energy.

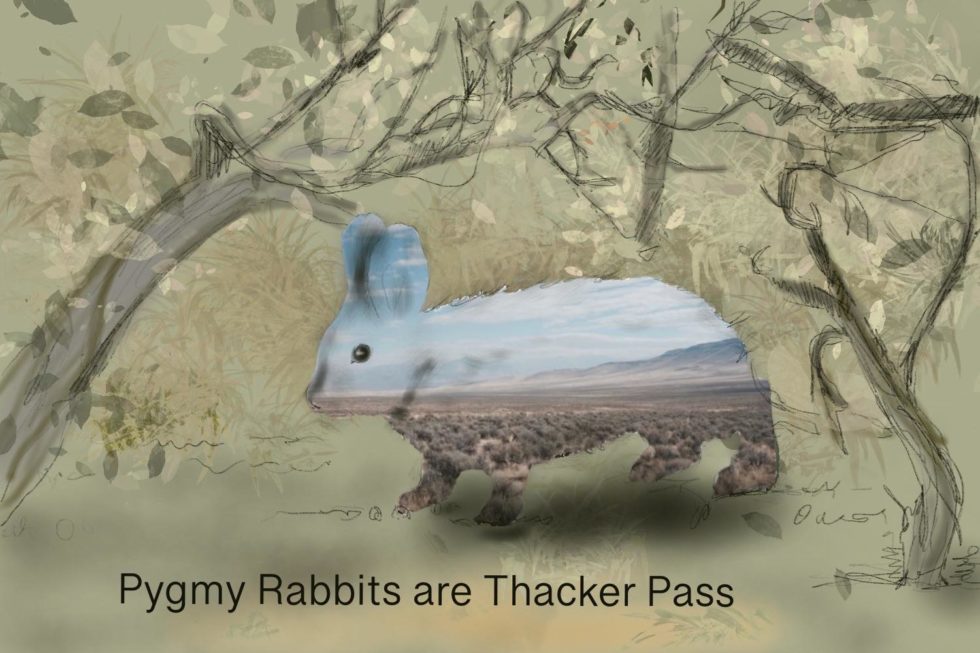

Featured image: Pygmy rabbit by Travis London

The small Pygmy rabbit is Thacker pass and Thacker Pass is Pygmy rabbits. This small rabbit is a target of many predators at Thacker Pass. The rabbits find their refuge in the form of the sagebrush plant or in the burrows that it makes in deep, soft soil. Much like the sage grouse, the pygmy rabbit relies on sagebrush not only for protection but for more than 90%. of its diet. The pygmy rabbit requires large expanses of uninterrupted shrub-steppe habitat. Unfortunately, right now the pygmy rabbit faces many threats. Conversion of indispensable sagebrush meadows for agriculture and development for oil and natural gas extraction, and now the lithium boom, are depleting an already fragile ecosystem. One more reason to resist.

For the past 25 days, there has been a protest camp set up behind me, right out here. This place is called Thacker Pass, in Northern Nevada, traditional territory of the Northern Paiute and Western Shoshoni.

This area here is the proposed site of an open pit lithium mine, a massive strip mine that will turn everything into a heavily industrialized zone.

This site, right now, is an incredibly biodiverse Sagebrush habitat. There are Sagebrush plants over a hundred years olds, cause it’s oldgrowth Sage. There’s Sage-Grouse. This is part of the most important Sage-Grouse population left in the entire state, Around 5-8 percent of the entire global population of Sage-Grouse live right here.

This is a migratory corridor of Pronghorn. One of the members of the occupation saw about 55 Pronghorns in an area that would be destroyed for the open pit mine.

There are Golden Eagles here, multiple nesting pairs. We’ve seen them circling over head. We’ve seen their mating flights, getting ready to lay their eggs in the spring.

There are Pygmy Rabbits here. There are Burrowing Owls. There are Gopher Snakes and Rattle Snakes. There’s Rabbit Brush. There’s Jack Rabbit.

There’s Paragon Falcon, or actually the desert variant of the Paragon Falcon, what’s known as the Prairie Falcon.

There are Mule Deer. We see them feeding up on these hills. There are Ringtail living behind this cliff behind me. There are Red Foxes. There are Kangaroo Mice. There are an incredible variety of creatures that live here. Many of whom I don’t know their names.

All this is under threat to create to create an open pit mine for lithium. To mine lithium for electric car batteries, and for grid energy storage to power these “green energy” transitions.

I’m not a fan of fossil fuels.

I’m not a promoter of fossil fuels. I’ve taken direct action for many years against fossil fuels. I’ve fought tarsands in Canada. I’ve fought tarsands pipelines in the US. I’ve fought natural gas pipelines, methane pipelines. I’ve stood on front of heavy equipment to block tar sands and fossil fuel mining in Utah. I’ve stood in front of coal trains to stop them from moving forward, to try and blockade the industry. I’ve fought the fossil fuel industry for many many years and will continue to do so.

What we need to recognize that the so called green energy transition that is being promoted is not a real solution. That’s why we’re out on the land. This is the place that is at stake right now. This is the place that is up to be sacrificed for the sake of this so-called green energy.

It was about a 175 years ago that the colonization of this region really began in earnest. That was when the first European settlers started coming across in Nevada. really setting up shops out here, in the mid-1800s. They mostly came for mineral wealth. They came for the gold, the silver. They came for mining. Nevada has been a mining state from the very beginning, and mining still controls the state.

I’ve spoken with some of my Shoshoni friends, my Goshute friends about the history of this: the invasion for mining. What happened was, the settlers came and they forced the indigenous population onto reservation. And they cut down the Juniper trees and the Pinyon pine trees. These were the main sources of medicine and food for many of the Great Basin Indigenous Peoples. I’ve heard it said that the Pinyon pines were like the Buffaloes to the Indigenous People out here.

Just like in the Great Plains, the settlers destroyed the food supply of the indigenous people. They forced them to participate into colonial economy using this violence. They forced them to participate in the capitalist system, in the mining system, in the ranching system. People were going to starve otherwise.

What happened in the mid 1800s was that men with guns came for the mountains. They started digging them out, blowing them up, turning mountains into money, carding that money away, and leaving behind a wasteland. That’s what’s been happening in Nevada ever since. It hasn’t stopped. That’s what we’re gonna see here unless it’s stopped.

The Lithium Americas Corporation, Canadian mining company that wants to build this mine: they raised 400 million dollars in one day a few weeks ago to try and build this mine.

Meanwhile the grassroots struggles to raise a few hundred dollars to help support people coming out here, camping, getting supplies, getting things we need, the travel to get people here. The camp is about a mile or mile and a half from here. There’s about seven or eight people out there.

We need more people to come out to camp. We need people to join us, to draw the line, to hold the line against this mining project.

It’s not just about this project here. I was at a panel discussion recently with some folks from the Andean Altiplano, what’s called the lithium triangle in South America. Argentina, Bolivia and Chile have this high desert region where the three countries meet. It contains about half the world’s lithium reserves. Lithium mining has been going on there for decades and it’s left behind a wasteland.

Indigenous People have been kicked out of their land. They’ve been dispossessed. Their lands have been poisoned. Their water has been taken.

Water usage is one of the major issues there, because it’s an extremely dry place, just like here. Nevada is the driest state in the US. And they wanna pump 1.4 billion gallons of water and use it to refine the lithium into its final product. 1.4 billion gallons a year.

The Queen River in the valley is already dry. The water’s already being overused.

You go back 200 years and there would be water there. There would be beaver dams. There would be fish. There would be wildlife in abundance.

This land is already in an degraded state compared to where it used to be, compared to where it needs to be.

The atrocities associated with this mine go on and on. This is an important cultural site for the Indigenous People of this region. This has been a travel corridor, through what’s now called Thacker Pass for thousands and thousands of years, an important gathering side. If you walk across this land, there’s obsidian everywhere across the ground. There’s all kind of flakes on the other sides of valleys, where indigenous people would gather obsidian and use it to make tools

This has been an important place for thousands of years.

Shoshoni signed a treaty, but they never ceded their land to the United States.

This is unceded land.

The Western Shoshoni never gave away their land. The US does not have legal title to this land. And the US government rejects that. They have appropriated something like a 175 million dollars, and set it aside to give it to the Western Shoshoni, if they will agree that the land was given to the United States. The Western Shoshoni has said “No. We won’t take your money. We want the land.” They have been fighting this fight for decades.

This is unceded territory. This land does not belong to the Bureau of Land Management. This land does not belong to the federal government.

This land belongs to the inhabitants of this land, people whose ancestors are in the soil. I don’t just mean humans. This land belongs to the Sagebrush, and the Pygmy Rabbits, and all those who have

Why don’t their voices get a say? Why don’t we take their preferences into account? What do you think they would say if we ask them, “Can we blow this place up?”

If Lithium America showed up and sincerely asked the Burrowing Owls, and the Sage-Grouse, and the Coyotes, and the Pronghorn Antelopes, “Can we blow up your home? Can we blow it up? Can we turn it into dust? Can we bathe the ground in sulfuric acid to extract this lithium which we’ll take away and make people rich, leaving behind a wasteland? Do we have your permission to do this?”

What do you think the land will say? What do you think the inhabitants will say? Do you think they will say it’s green? Do you think they’ll say:

“This is how you save the planet, by destroying our home?”

I think this is an important issue, not just because of what’s happening here, but because of what it means. Because of what it symbolizes.

When I was a young person, I was very concerned about what was happening to the planet. I was very concerned about the ecological crisis: the rainforest being chopped down, global warming, ocean acidification, the hole in the ozone layer.

I care about these things. I’ve cared about them ever since I was a little kid.

It’s hard to be a human being and have a heart, and not care about it unless you’re broken in some way.

I wanted to figure out what could be done. So I started reading about these issues. And of course what I was taught from a very young age was that solar panels and electric cars were going to save the world. That’s what I learned. That’s what the green media taught me. They taught me implicitly it’s okay to sacrifice places like this. They taught me it’s okay to sacrifice places like this if it means we can have electric cars instead of fossil fuel cars.

We don’t need cars at all. That’s the thing. And this is a hard message for people to hear because people don’t want to be told No. We’re not used to being told No in this culture. You can’t have that. It’s not okay for us to continue in this way.

We’re not used to this message. We’re used to getting whatever we want, whenever we want it.

That’s for the most part across the board. The average person in the American society lives with the energy equivalent of a hundred slaves. We live a life of luxury, like we had a hundred slaves working for us for twenty four hours.

That’s what the fossil fuel has brought to the modern era. That’s what this energy glut has brought to us. This mindset that we could have whatever we want, whenever we want. That’s something we need to get over. That’s something we need to change.

For the past five or six years, I was working on a book called Bright Green Lies: How the Environmental Movement Lost It’s Way and What We Can Do About It. My co-authors and I, in this book, really dive into these problems with details of the so-called green technology in great details. Things like solar panels, wind turbines, electric cars, energy storage, batteries.

Not only these things, but a lots of the other “solutions” that are accepted as dogma in the environmental movement, like dense urbanization. We debunk these things in the book. These things are not going to save this planet. We can’t get around the problems we have found ourselves in.

We’re in a conundrum. This culture has dug itself into a very deep hole.

A lot is going to need to change, before we find ourselves in any resemblance of sustainability, of sanity, of justice, of living in a good way.

Earlier, I came around the corner in the mountains, and it felt like a punch in the gut because I had the premonition of no longer seeing this swab, this rolling expanse of old-growth Sagebrush, but of seeing an open pit. Seeing a mountain of tailings, of minewaste, of toxified soil. I had the premonition of seeing a gigantic sulfuric acid plant and processing facilities all through what is now wild. Where the Foxes run, where the Snakes slither between the Sagebrush, where the Golden Eagles wheel overhead.

That’s why I’m here to fight. I don’t want to see this turn into an industrial wasteland.

I don’t think many of us do. I think a lot of people are befuddled and confused by all these bright green lies. A lot of people buy into this crap. But a lot of people don’t. A lot of people understand that we need to scale down. A lot of people understand that we need to reduce our energy consumption, that we need to degrow the economy. That the latest and greatest industrial technology isn’t going to save us, magically.

This isn’t a tooth fairy situation, where electric cars will appear under our pillows and save the day. A lot of people understand this. That’s why for me, a big part of the battle is not education. A big part of the battle is power. A big part of the battle is actually stopping them.

For more on the issue:

New rule for living in America: We need to ask ourselves, every morning, “What am I going to do today to speed up the collapse of civilization?” And every night before we go to sleep, “What was done today — by anyone, anywhere — to speed up the collapse of civilization? And what can I do to help?”

The morning and evening questions aren’t exactly the same, because some days we might have a chance that just appears in front of us, unplanned and unexpected.

Among the few things I’m personally proud of was just doing what any one of thousands of people could have done one day, but didn’t. It didn’t change the world, and it only saved one life. But I hope some of the people I pissed off that day thought about it later, and possibly changed their views on life, death, and priorities.

I worked for a courier company at the time, and was making my morning run from Silicon Valley toward San Francisco, around 11:00 in the morning, in heavy traffic on 101. It was clear and warm, and I noticed something small and oblong, slowly moving north in the shadow of the center divider. At first I thought it was a paper bag, being moved along by air turbulence from the traffic.

Then I did a doubletake. The moving object wasn’t a piece of trash at all. It was a young adult possum, stranded in the middle of the freeway, hopelessly looking for a way out. Since possums are nocturnal, this little guy had been stuck there since at least since dawn, and had somehow survived.

None of the other drivers seemed to notice. Or, if they did, they dismissed it with the usual rationale: “It’s just an animal.” “It’s Animal Control’s problem.” “It’s just a matter or time before it gets killed.” Or, at best, “I don’t know what I could do. And I could cause a 12-car pileup if I stopped.”

I didn’t know what to do, either. But I knew that if it were a toddler, EVERYONE would have stopped, and at least one in ten if it had been a lost dog. But this was no time to play the superior species card.

By the time I confirmed that it was a live, healthy animal, it was already too late to stop. So I hurried to the next exit and doubled back, hoping the possum would still be alive when I got there.

When I found it again, I slowed to possum speed dor a closer look. It looked at me briefly and showed its teeth, but kept walking. With horns blaring behind me and middle fingers waving hello from the side, I stopped. Knowing that possums are not aggressive, I was prepared to throw my jacket over it, and hope it would “play possum,” instead of giving me a nasty bite.

But nothing that dramatic was necessary. I had a mail tub on the floorboard, dumped its contents, and flipped it over to cover the possum. I slid a large piece of cardboard under the mail tub, gently turned it over, and put it on the passenger seat next to me.

I took a peek, and saw that the animal was unhurt. Its only souvenir from a long brush with death was a scrape along its right side, about an inch wide and four inches long, where I guessed a speeding vehicle with a sharp edge had just grazed it, shaving off a patch of fur, and reminding my new passenger to stay as close as possible to the freeway divider.

Knowing there was a nature preserve a few miles back, I made my delivery, headed south again, walked my new friend a quarter-mile down a hiking trail, and released it into some tall grass beside a tree. It showed me its teeth again, examined and licked the scrape on its side, and waddled away.

But what made me so proud of that morning wasn’t what I did, which was nothing but what thousands of other drivers should have done — and surely would have done, it it had been a child or a dog. What I was so proud of was the possum, its will to live, its determination to survive, and one of nature’s rare and small victories against the onslaughts of civilization, pavement, cars, and our self-important rush to be somewhere we shouldn’t be.

And if you’re thinking, “Fine for him, but not for me,” don’t. Some of the most fun I’ve ever had was in my few animal rescue adventures, which have included a deer, four possums, several ducks, a seagull, a cormorant, a snake, a tortoise, two rays (left to suffocate with fishhooks in their mouths), a small shark in a similar predicament, a few pigeons, several dogs, and countless cats. And the only injuries I have to report were a bite on the nose from the seagull, and a few red marks on my hand fro the cormorant.

But while individual rescues are gratifying, we have to do more, and take actions that really disable industrial enterprise. Look for openings. With a civilization that chews up almost 200 million tons of Earth a day, the opportunities literally are endless.