by DGR News Service | Oct 1, 2019 | Alienation & Mental Health, Culture of Resistance

by Liam Campbell

“Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, whereas all of Los Angeles and the America that surrounds it are no longer real, but belong to the hyperreal order and to the order of simulation.” — Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

Reality prevailed on Earth for untold millions of years. Base elements, microbes, algae, fungi, animals, and plants, they existed in complex and changing configurations; these variations of life were deeply rooted in an objective, singular reality. For our ancestors, an apple was an apple, it existed independently and without symbolic constraints or meaning. Then we invented language, possibly the first true simulation, which allowed us to invoke the idea of an apple without the presence of one. This abstract concept of an apple became an amalgamation of all of our individual and cultural experiences of a thing, and the idea of an apple could only exist in relationship to other concepts of “not apple.” Baudrillard called this phenomenon a “simulacrum,” which is a representation or an imitation of a thing.

For a long time, our simulacra were rudimentary and poor imitations of reality. No matter how many words we invented to describe an apple, our simulation remained unconvincing and easily distinguishable from the real thing. As our skill at painting progressed we managed to produce visually convincing simulacra of apples, but they still smelled like paint and were inedible. As our understanding of chemistry advanced we discovered chemicals which smell like our shared conception of an apple, allowing us to convince both our eyes and noses, but the simulacrum of the apple remained unconvincing to our other senses. Now, through genetic engineering, we have reached the point where we can create a simulation of an apple which is not a “real” apple, it is an imitation based on our idealistic conception of the idea of an apple. This is hyperreality, an inability to distinguish between reality and a simulation, and it permeates almost every aspect of our postmodern experience.

In his seminal work, Simulacra and Simulation, Baudrillard proposes that hyperreality unfolds in four stages:

- Reasonably accurate images or copies of reality. For example: photography used to faithfully document real scenes from a war.

- Perversion of reality where images or copies of reality appear to be the real thing, but actually create a false impression of reality. For example: a photograph which accidentally appears to make an innocent person look guilty.

- Obstruction of reality where images or copies intentionally mask or obscure reality. For example: a photograph where a government intentionally fabricates an event in order to manufacture consent.

- Complete simulacrum where it becomes impossible to differentiate between reality and simulation because the simulacra are absolutely convincing and permeate every aspect of life. At this stage, it is unnecessary to intentionally obscure reality because people give up the pursuit of objective reality as an overly sentimental notion and an exercise in futility.

Baudrillard argues that most of us have entered into the last stage, that of complete simulacrum, because we are indoctrinated from birth to perceive things as more than they are. Upon seeing an apple, we immediately think of the asbtract concept of “apples,” we think of our cultural relationships with that concept, and then we relate that concept to all similar or dissimilar concepts. Moreover, many of us have only experienced genetically modified apples, so even our sensory comprehension of “apples” is based on simulacra.

From this perspective, we have become profoundly and potentially irrevocably detached from objective reality. Although we can make decisions which will lead us closer to, or farther away from, objective reality, we can never return to a state of complete alignment. Our current trajectory is leading us into an extreme form of simulacrum where our experiences detach entirely from any connection to reality — even our most intimate personal relationships are increasingly shaped through lenses of reality television, consumerism, counseling, and commodification. How will we know when we have fully detached from the real? Baudrillard, even in the 1980s, made a strong case for the argument that we long ago crossed that threshold.

Today, objective reality is forcing itself back into our consciousness in the form of climate and ecological collapse. Our collective decisions to manufacture and inhabit hyperreality have detached us from the systems which are cannibalised to sustain our fantasies. Today’s children are as likely to believe that eggs come from grocery stores as chickens, and even the average adult has no conception whatsoever that their favourite chocolate spread is produced from the charred bones of orangutans. Baudrillard points out that, in previous cultures, animals were often ritualistically killed before being eaten; although this act may seem cruel, on the surface, it reminds people that the animal was a living thing and that some degree of cruelty was involved in converting that life into meat. By contrast, most industrialised humans are so far removed from the realities of their consumerism that they view meat as an asbtraction, little more than a commodity which has no history before having been selected among other pieces of plastic-wrapped meat from a refrigerator. Indeed, hyperreality has advanced so far that there are now convincing simulacra of meat, made up of the same material, but having never lived at all. Does this avert the suffering and absolve us of cruelty, or does it merely obscure the cruelty under increasingly abstract layers of exploitative farming, native species annihilation, and habitat destruction?

At some point these increasingly sophisticated delusions will crash down around us; possibly as a result of ecosystem collapse, or maybe we will become so dehumanised that we will simply choose to cease to exist for lack of any sense of meaning. It does seem like the further we depart from our basis in objective reality, the more dissatisfied we become with our own existence. For the time being we fill that growing void with additional consumption, but it’s inclear whether we’re motivated more by an amibition to achieve some fantastical outcome, or if we’re simply afraid to die and willing to abandon any sense of meaning in exchange for delaying death or physical by a few more years. What’s evident, at least to me, is that our lives are technologically advanced but culturally backward.

by DGR News Service | Sep 25, 2019 | Climate Change

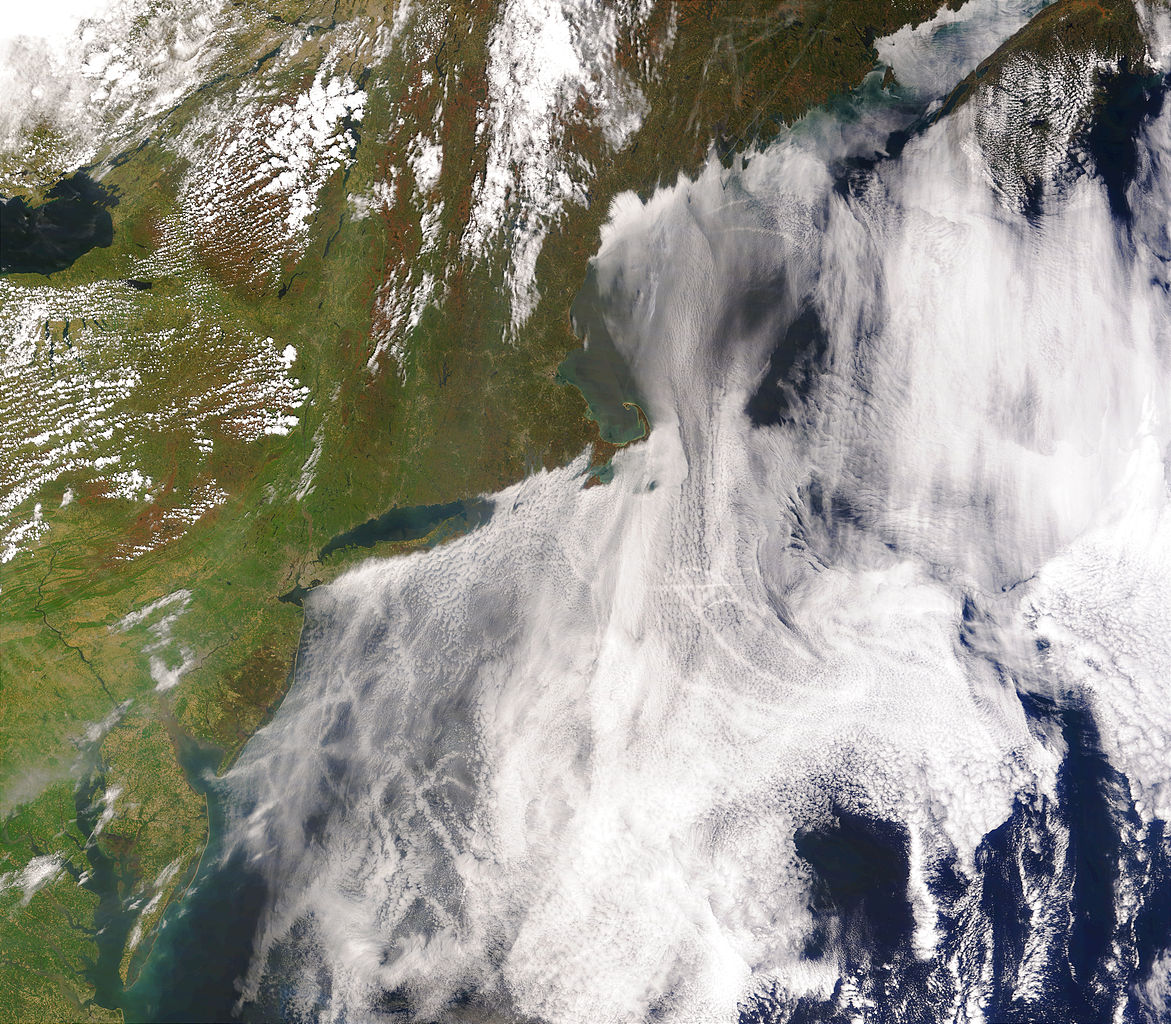

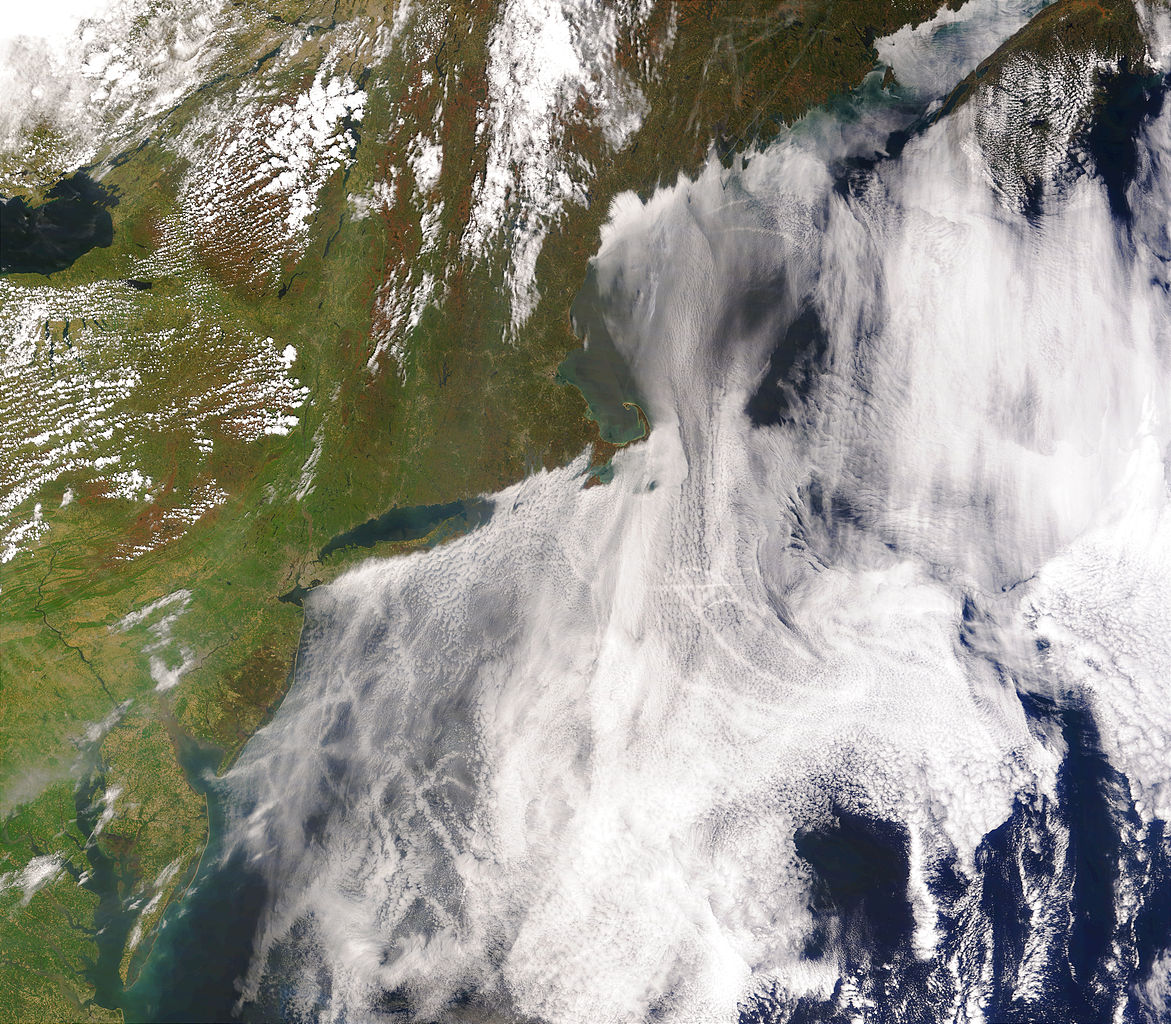

Featured image: Linear clouds in this satellite photo show the path of large ships. Exhaust from the extremely polluting bunker fuel these ships burn acts as a nucleus for condensing water vapor, forming clouds. One container ship releases as much pollution as 50 million cars. Public domain photo.

By Max Wilbert

The Global Climate System

Global climate can be understood as a simple energy balance equation. When climate is stable, energy inputs (sunlight hitting the Earth) matches the amount of energy lost to space through radiation. Industrial civilization has upset this balance by destroying forests, plowing grasslands, damming rivers, and digging up and burning coal, oil, and gas. These processes all release greenhouse gases, which trap additional heat inside the atmosphere. This is called radiative forcing.

This has gradually changed the energy balance of the entire planet. Since 1998, these greenhouse gases have caused an amount of energy equivalent to nearly 2.8 billion Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs to be captured inside the Earth’s atmosphere. Most of this heat has been absorbed by the oceans.

We know the consequences of this: ocean acidification, glaciers melting, droughts, heat waves, floods, stronger hurricanes, crop failures, migration, and so on. The ramifications of global warming are catastrophic and pervasive to essentially every aspect of human and non-human life. But some of the details of global warming are less often discussed.

What Are Aerosols?

One of these rarely-discussed issues is the aerosol masking effect. “Aerosols” in climate science are defined as collections of airborne solid or liquid particles, with a typical size between 0.01 and 10 µm (micrometers) that reside in the atmosphere for at least several hours. Aerosols may be of either natural or anthropogenic origin. Aerosols may influence climate in several ways: directly through scattering and absorbing radiation, and indirectly by acting as cloud condensation nuclei or modifying the optical properties and lifetime of clouds (see Indirect aerosol effect). Examples of aerosols include dust, volcanic ash, pollen, soot, sulphates, even bacteria.

Some of the most common aerosols come from coal, driving cars, and fire for land clearance. When entering the lungs, these particles are extremely hazardous to health of all creatures, and are estimated to kill about 5.5 million people per year. This is one reason that pollution is estimated to be responsible for roughly 40% of all human deaths.

Aerosols also cool the planet by reflecting incoming solar radiation back into space. In the past, researchers have estimated this blocked as much as half of the warming caused to this point. As Dan Bailed wrote online, “It has long been conjectured that an immediate cessation of the burning of fossil fuels would be swiftly accompanied by a spike in surface temperatures (warming rates might spike from 0.2 C per decade to as much as 0.4 to 0.8 C per decade).”

Does Aerosol Masking Make Resistance Counterproductive?

This has been a common question for us here at Deep Green Resistance:

“What’s your take on the aerosol masking effect? Some people believe it is actually protecting the Earth from runaway climate change. If industrial collapse happens, wouldn’t this cause a decrease in aerosols and result in rapid warming? Wouldn’t this mean that life on earth is doomed even faster? Won’t reducing industrial emissions just result in faster warming?”

We have for years regarded this as a false double-bind, or an example of a legitimate concern twisted into an excuse for inaction. Using aerosol masking as an excuse for not shutting down fossil fuel infrastructure is an exercise in cowardice, in holding change hostage, in a sort of blackmail: damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

As you know, the only way out of a double-bind is to smash it.

New Science Reduces Concerns Over Aerosol Masking

But even legitimate concerns may be laid to rest by new science published in Nature this month. In the paper, two researchers Shindell and Smith note that reductions in fossil fuel burning, and thus in aerosols, “do not produce a substantial near-term increase in either the magnitude or the rate of warming.” This warming, they explain, would be negligible “at essentially all decadal to centennial timescales.”

Their conclusion: “We find that any climate penalty associated with the rapid phase-out of fossil-fuel usage… is likely to be at most 0.29 °C.” While climate science is complex and new findings could always change the situation, our conclusion is straightforward as well.

The medicine is not worse than the disease. There is only one clear path to a livable planet: stopping the fossil fuel economy as soon as possible. The sooner civilization crashes, the better.

by DGR News Service | Sep 23, 2019 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

By Derrick Jensen

This article was originally published in the Fair Observer, and is republished here with the authors permission. Featured image by NaveenNkadalaveni, CC BY-SA 4.0.

The Amazon is burning. This is what the end of the world looks like. Oh, and there’ll be more forests burned, more forests felled by chainsaws, more wetlands drained, more rivers dammed, more grasslands plowed, oceans further toxified and emptied of fish.

And each of these is what the end of the world looks like.

The end of the world looks like factory trawlers pulling in net after net full to bursting with fish — the fish’s eyes popping out from the pressure of all those bodies squeezed together. It looks like puffins starving to death. It looks like emaciated polar bears. It looks like whales washing up on shore and walruses not finding ice on which to rest.

The end of the world looks like plows digging into grasslands, turning over soil and killing all who live there, even down to bacteria. It looks like rows of monocrops, as far as the eye can see.

The end of the world looks like humans staring at screens, clucking their tongues at the destruction of forests far away, never noticing that they themselves — whether they’re in London, New York, Paris, Rome, Athens, Beirut, Beijing or Baghdad — are standing in clear-cuts.

The end of the world looks like cities, with most of their residents never giving a thought to who and what was killed to build that city, never giving a thought to who and what was killed to mine, manufacture and move everything they consider necessary to their lives, and never thinking about what is necessary to life and what is not.

The end of the world looks like humans turning the planet to human use. Or rather attempting to, because it’s not possible to turn this wild and fecund Earth totally to human use, and this attempting is itself what is causing the end of the world.

From the beginning of this culture, it has been so. When you think of Iraq, is the first thing you think of cedar forests so thick that sunlight never touches the ground? That’s what it was like, prior to the beginning of this culture. The first written myth of Western civilization is Gilgamesh deforesting the hills and valleys of Iraq to make a great city.

Have you heard of Mesopotamian elephants? Most of us haven’t. They were exterminated to make way for this culture. And when you think of the Arabian Peninsula, do you think of oak savannas? These forests were cut for export to fuel the economy, to build cities.

The Near East was heavily forested. We’ve all heard of the cedars of Lebanon. They still have one on their flag. The great forests of North Africa were felled to make the Phoenician and Egyptian navies. Greece was heavily forested. So was Italy. So was France. The great forests of Britain came down to make the navy that allowed the sun never to set on the British Empire.

This is what this culture does. Forests precede us and deserts dog our heels.

The end of the world was not written into human existence. For most of our species’ time on Earth, we’ve lived sustainably. The Tolowa Indians lived where I live now for at least 12,500 years, and when the dominant culture arrived, salmon still ran so thick they turned entire rivers “black and roiling” with their bodies. There was no such thing as “ancient redwood forests.” There was only “home” — a home filled with trees thousands of years old, a home filled with nonhumans in abundance most of us literally cannot conceptualize.

Can you imagine — and this moves us across the continent — flocks of passenger pigeons so large they darken the sky for days at a time, flying 60 miles per hour and sounding like rolling thunder? Can you imagine so many whales that the air looks foggy, just from their breath? Can you imagine fish in such abundance that they slow the passage of ships? Can you imagine entire islands so full of great auks that one European explorer said they could load every ship in France and it would not make a dent? Well, they did, and it did, and the last great auk was killed in the 19th century.

How did the world get to be so full of life in the first place? By each creature making the world richer by living and dying. Salmon make forests stronger by their lives and deaths. Redwood trees do the same. Buffalo make grasslands stronger by their lives and deaths. Wolves do the same. And humans can do the same. But not living the way we do.

The Tolowa were not alone in their sustainability. There have been sustainable cultures the world over. The San of southern Africa, for example, evolved in place. They have lived there, in human terms, forever.

And how have humans lived sustainably in place? Simple. By not destroying the places where they lived, and by not destroying other places either. By improving the habitat on its own terms by their presence. The Tolowa made land-use decisions, just as all other beings on the land do, and just as we make land-use decisions. But the Tolowa made these land-use decisions on the assumption they would be living in a place for the next 500 years. That assumption changes everything about how you make decisions and how you live. It is the difference between life and death, between sustainability and the end of the world.

The end of the world was not written into human existence. It was, however, written into the story of Gilgamesh. The end of the world is written into this way of life of converting the Earth solely to human use. It was written into existence with the plow, and with the cities the plow makes possible.

The logic is simple and inescapable. If you convert the land that previously grew bushes and trees that fed elephants into wheat that feeds humans, you can grow more humans per hectare. Many of these humans can become a standing army. And you can use those trees you cut down to build ships of war. You now have a competitive military advantage over those who live sustainably, over those who do not destroy their land base. Further, because you’ve degraded your own land base, you must expand into other land bases. But fortunately for you, you’ve got a standing military.

This is the last 6,000 years of history. This is the story of the end of the world.

More than 90% of forests on the planet have been destroyed. The same is true for wetlands, grasslands, seagrass beds, large schools of fish, wildlife populations in general.

This culture is killing the planet. It doesn’t have to be this way. Not every culture has lived this way. Not every culture has killed the planet.

Recently, more and more people are talking about the possibility of human extinction. That possibility has entered our consciousness enough that, in December 2018, The New York Times published an op-ed asking whether it would be better for the Earth if humans went extinct.

As the Amazon burns, here’s the thing that haunts me. How is it that this culture can contemplate the end of the Amazon rainforest, contemplate the end of elephants, great apes, insects, fish in the oceans? How is it that it can blithely destroy life on Earth? How is it that it can with not much horror contemplate human extinction, but cannot contemplate stopping this way of life?

If aliens came from outer space and did to Earth what this culture is doing — change the climate; burn the Amazon; deforest the planet; vacuum the oceans and put dioxin in every mother’s breastmilk; and bathe the world in plastics, endocrine disrupters and neurotoxin — we would know exactly what to do. We would resist. We would fight as though our lives depend on it. We would destroy the aliens’ infrastructure that allows them to wage war on the planet that is our only home.

Or, put another way, if the Amazon could take on human manifestation, what would it do? If salmon could take on human manifestation, how long would dams stand? If humans from the future could come to our time, how would they act?

As the writer Lierre Keith often says, “If there are any humans left 100 years from now, they are going to ask what the fuck was wrong with us that we didn’t fight like hell when the world was going down.”

Many of us who know history might have fantasies of how we would have acted were we alive under German occupation in World War II or under British colonial rule. Right now, we are facing the end of the world. We have the opportunity and the honor to protect the planet that gave us our lives.

The time is now. Roll up your sleeves and get to work. Life on this planet needs you.

by DGR News Service | Sep 19, 2019 | Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction, The Problem: Civilization

by Liam Campbell

Skies in North America are falling silent. No, airplanes haven’t been grounded yet, unfortunately. It’s the birds who are missing. Since 1970 bird populations in the United States and Canada have collapsed by 29% (that’s 2.9 billion fewer birds), according to a recent report published in the journal Science. David Yarnold, president and chief executive of the National Audobon Society has declared a “full-blown crisis.” The results surveyed over 500 species and revealed that even historically abundant birds like robins and sparrows have begun to disappear at an alarming rate.

Healthy bird populations are critical. Without them, ecosystems become unbalanced, pollination rates diminish, seeds are not spread effectively, and forests become unhealthy. Although the public has focused on a few saving a few icononic species, like bald eagles and spotted owls, less popular species like sparrows can actually have a bigger impact; their disappearance may cause a cascade of devastating ecological failures. What’s staggering about this research is that it revealed that almost all bird populations, across the board, are plummeting at an alarming rate. Even starlings, an invasive species which are historically abundant and reproduce rapidly, have experienced a 49% decline.

These losses are not limited to North America. Europe is witnessing similar declines and, like in America, grasslands are worst hit. Modern agricultural practices and human development are the leading causes of plummeting populations, with neonicontinoid pesticides causing particular harm. In 1962 Rachel Carson predicted many of these outcomes in her book Silent Spring. When you step back and look at the situation, it’s obvious what’s really killing these birds: human overconsumption. The only way to save these birds, and the ecosystems which rely on them, is to protect their remaining habitats, stop the use of toxic chemicals, and reduce the footprint of humanity on the world.

by DGR News Service | Sep 17, 2019 | Agriculture, Biodiversity & Habitat Destruction

by Liam Campbell

In 1997, forest fires in Indonesia grew so large that they accounted for 40% of global emissions during that period. The Borneo rainforest is the most ancient in the world, having taken 120 million years to evolve into its current state of rich diversity. Indonesia is also home to some of the world’s largest tropic peat bogs, deep and vast stockpiles of carbon which have formed over millennia. When these peat bogs ignite they are almost impossible to extinguish because they burn deeply into the Earth and smoulder for weeks or even months, and they can also release millions of years worth of stored carbon into the atmosphere very suddenly. Although seasonal fires are common in the Borneo, climate collapse has made the rainforest more susceptible, and the magnitude of this year’s fires are already unfathomable.

Many of the fires we’re seeing right now are caused by exploitative agriculturalists who are burning the rainforest to open land up for human crops and livestock. In doing so, they are destroying 120 million years of evolution and rapidly annihilating one of the Earth’s most diverse and ancient living ecosystems. Although Indonesia claims to be doing “everything in their power” to extinguish the fires, they are not doing nearly enough to prevent them from happening in the first place. Only about 200 suspects have been arrested in relation to the arsons, and it is likely that many of them will be released without charges or consequences. It is understandable that individual farmers may be tempted by the prospect of opening more land for profitable exploitation, but the act of burning such an ancient ecosystem is among the worst crimes a human can commit; it not only endangers the rest of the planet’s climate, it destroys one of the most ancient living systems on this planet.

Most of the fires were started by palm oil plantations, which are often owned by large corporations. Officials estimate that about 80% of the fires were set intentionally and they now number in the thousands, with 2,900 especially bad hot spots. In all, only about two dozen palm oil plantations have been temporarily shut down in connection to arsons, they are primarily owned by Malaysian and Singaporean companies. These companies are unlikely to face significant charges or repercussions, and will likely return to increasingly profitable business after paying fines.

by DGR News Service | Sep 16, 2019 | Colonialism & Conquest, Indigenous Autonomy

At the base of Mauna Kea, the world’s tallest mountain and the first point on earth where raindrops touch the earth, the largest land defense action in modern Hawaiian history is currently in taking place and the entire movement is being guided by love.

For Indigenous Hawaiians, it could not be any other way. In Hawaiian cosmology, Mauna Kea is the origin place of the Hawaiian people. The Hawaiian genealogy teaches that the summit of the mountain is the meeting place of Earth Mother, Papahānaumoku, and Sky Father, Wākea and that the Hawaiian people are directly descended from this union. Therefore, Mauna Kea is utmost sacred ground; it is the piko (umbilical cord) of Native Hawaiian existence.

The mountain is home to innumerable lepa (altars), akua (gods and goddesses) burials and ceremonial sites that have been in use since the existence of the Hawaiian people. Holidays and ceremonial traditions are carried out on the mountain, with families maintaining and visiting their specific lepa generation after generation. For some families, newborn babies umbilical cords are brought to the aquifer at the summit of the mountain, to ground them in their homelands just as their ancestors had done.

Like Christians in church or Muslims in a mosque, being on the Mauna necessitates acting in one’s highest state of being. In the Native Hawaiian language, this is referred to as “kapu aloha” or state of love. Although there are currently innumerable Indigenous land rights and sovereignty frontlines around the world, Mauna Kea is distinct in that every action being taken for the protection of the mountain is being guided entirely by love for the land, for the community and for all of creation.

Understanding the TMT

Although Mauna Kea is both crown land (lands belonging to the former king of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kamehameha) and is zoned as a conservation area, there are already 13 telescopes constructed on the summit of the mountain dating back to 1968. Many of these were built without proper permits and against the wishes of the local community. While some remain in use, others have been abandoned and left dormant. In fact, the Thirty Metre Telescope (TMT) was initially slated to be built in 2015 but following island-wide protests, 31 arrests and global pressure was forced back into the Hawaiian courts.

The mountain is not only spiritually significant but also ecologically fragile, with unique biogeoclimatic zones and a freshwater aquifer that is the source of freshwater for the Big Island. For decades there has been concern over mismanagement of the observatories; including waste management and mercury spills. Despite these issues remaining unaddressed, the proposal to build the world’s largest telescope – led by the University of California and partner institutions from Canada, China, India, and Japan, as well as the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation – it was approved in the Hawaiian courts. The granting of the building permits came despite years of oppositional testimony from Native Hawaiian elders, knowledge keepers, professors, legal scholars, and local residents.

Plans for the Thirty Meter Telescope would see it constructed 18 stories high, 9 stories down and 5 acres wide. The design for the 1.4 billion dollar project was created in Port Coquitlam by Guy Nelson, CEO of Empire Industries which owns Dynamic Structures. Although there has been an environmental impact statement carried out by the University of Hawai’i at Hilo (one of the invested parties for the TMT), there is deep mistrust amongst the Mauna Protectors about the depth and accuracy of the report relating to previous mismanagement of telescopes in the area as well as potential ulterior economic motives driving the construction of the TMT from politicians.

While the TMT project manager has stated that they would be happy to build the project at an alternative location in the Canary Islands, Hawaiian politicians have taken desperate action to push it through, including declaring a state of emergency in order to bring in the National Guard. In addition to the cultural impact of the TMT, there remain many questions regarding the environmental impacts a structure of this size would have in a time of extreme climate change. Mauna Kea is a storm barrier for the rest of the Hawaiian archipelago that has repeatedly shielded the other islands from storm systems, as well as provided an essential freshwater source for the Big Island.

An occupied kingdom

In order to understand the uprising of land and cultural defense that is currently unfolding on Mauna Kea, a certain level of historical context is necessary.

Although many outsiders have been programmed to see Hawai’i as an American State, the majority of Indigenous Hawaiians understand themselves to be living under the occupation of the US government and military, as Hawai’i was a sovereign kingdom and internationally recognized as an independent nation. On January 16, 1893 the nation was invaded by United States marines which led to an illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government the following day. Nearly a year later in his message to Congress, President Grover Cleveland acknowledged that this was an unlawful act and advised it’s a reversal. Although this advice was never heeded, in 1993 – one hundred years later- President Bill Clinton signed legislation apologizing for the U.S. role in the 1893 overthrow but the apology did not provide federal recognition to Native Hawaiians like the federal laws provided to Native American tribes.

Although much of the world does not know this history, the Native Hawaiian people have never forgotten the injustice. And like most other Indigenous nations whose lands are being occupied by colonial states, the grievance of land theft and unlawful occupation was just the first in an endless list of human rights breaches and transgressions. In Hawai’i, this includes the military occupation on many of the islands, where land is often used for target practice for uncontained bombing. The Disney-fication and gentrification of the Islands have also led to Native Hawaiians being pushed out of their original communities and away from traditional ways of life. The rising cost of housing and economic incentive to develop land for vacation and retirement housing has meant that homelessness is a significant issue for the Original Peoples of the Islands. Additionally, the overdevelopment, ecological mismanagement and use of the territory as a military testing sacrifice zone have created species and habitat endangerment that has led to the Department of Lands and Resources policing Native Hawaiian peoples from being able to carry out traditional forms of sustenance such as fishing and trapping. After 126 years of fighting for basic rights and recognition as Indigenous people, Mauna Kea has become a turning point and united Native Hawaiians to come together in aloha ‘aina (love of the land) and say – no more.

Pu’uhonua o Pu’uhuluhulu: A new kind of frontline

Following the July 10th, 2019 announcement that construction would begin the following week, a small group of 33 Native Hawaiian kupuna (elders), kumu (knowledge keepers), and kia’i (land protectors) drove to the base of Mauna Kea to set up camp. When they arrived on the evening of July 12th, there were just 13 cars.

Camille Kalama, a lawyer who is part of HULI (Hawaiian Unity and Liberation Institute) and one of the first to arrive at the mountain, shared that upon their arrival there was no formal plan or sense of whether others would join them. But by the end of that first weekend, the group had grown to 500.

Under the authority of the Royal Order of Kamehameha (an order of knighthood established by King Kamehameha V that dates back to 1865) and guided by Native Hawaiian ceremonial protocol the camp at the base of Mauna was deemed a Pu’u Honua (sanctuary) wherein kapu aloha (a state of love and respect) was put into effect. Under kapu aloha protocols, everyone is welcome as long as they act with aloha ‘aina (love of the land), treat others with kindness and respect, refrain from swearing and do not bring in drugs, alcohol or cigarettes. As one of the leaders of the movement, Pua Case repeatedly stated, “We shall not leave one grain of rice on this land”.

Early in the week, in anticipation for the arrival of construction trucks and state police, a frontline was established under the guidance of the kupuna who insisted they be the first line of defense. Behind them, a group of protectors chained themselves to the road on a cattle grate. From the inception of this frontline, kupuna have remained day after day blocking the main access road.

On Wednesday, July 17th, construction vehicles arrived escorted by local police. Within hours, 35 kupuna in their 70s and 80s were arrested. Many of whom needed walkers to make it to the police vans and others who had to be pushed in their wheelchairs; their younger counterparts wept, sang and prayed as they walked behind each individual who was escorted away by law enforcement. By the middle of the day the police had retreated, while the footage and images of elderly Mauna protectors streamed around the world. By mid-week, thousands were on the mountain and a small self-sustaining community had been created, named Pu’uhonua o Pu’uhuluhulu (roughly translated to Fuzzy Mountain Sanctuary after the hill facing Mauna Kea). Dozens of solidarity actions began popping up across the Hawaiian Islands, as well as in mainland USA, Canada, Aotearoa, and Japan, among others.

Why We Should All Be Paying Attention

While Mauna Kea has certainly been receiving ample international media attention, what many of the news reports are not describing how kapu aloha has remained the guiding principle of everything that is occurring from the Mauna protectors.

What has been created at Pu’u Honua o Pu’uhuluhulu in a few short weeks is nothing short of extraordinary. Every morning begins with prayer, oli (chanting), mo`olelo (story) and cultural activities including hula; kupuna set the tone for the day with reminders of what it means to be in a state of kapu aloha and provide necessary information for all those staying at the pu’uhonua. Every evening ends in much the same way.

All-day long, rain or shine, storytellers, dancers or musicians perform for the kupuna and anyone else who wants to witness and learn. The Pu’uhonua feeds three warms meals to anywhere from hundreds to thousands of people a day. There are dozens of latrines set up that are regularly cleaned, pumped out and fully stocked. There is a medical station, childcare, legal advisors and an area where masseurs and healers provide bodywork to anyone who seeks it. A free university has been set-up that runs four sessions a day, with five distinct classes in each session from 9:30 am to 3:30 pm; as one of my instructors there said, “its a place where tuition is free, everyone is welcome and the bathrooms are gender inclusive”. There is daily non-violent direct action training, which is mandatory for anyone planning to stay on the mountain. There is even a designated team of crossing guards who ensure the safe crossing of pedestrians, highway traffic, and delivery vehicles all day every day. While crossing, it is common for both pedestrians and crossing guards to be calling mahalo (thank you), aloha (love) and ku kia’i mauna (guardians of the mountain).

All of this is being run entirely by layers of volunteer leadership. The people who have come to protect the mountain have also begun to embody the principle of carrying deeply for one another, and it is working. Other than love and service, there is no currency on the mountain and yet everyone from small children, teens, families, and elders are fully cared for. As soon as you enter the pu’uhonua you can feel this shift, as though a doorway to another way of being has been created at the base of the world’s tallest mountain.

Although I was not present for the arrests, while I was on the Mauna I was told that as the kupuna where being taken away by police, they were praying for them, telling them they were not angry with them, that they understood. As is stated in Mathew 5:44, “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you”, what the kapu aloha embodied at Mauna Kea is so powerful that not even those who have come to destroy the mountain itself can break that way of being.

I wish the world could understand that the Mauna is a church; and what is taking place there now is sacred, people are living in harmony and ceremony with one another and the land, and showing us all that another world is possible.

Global Significance

In the three weeks, Pu’uhonua o Pu’uhuluhulu has become a beacon for Indigenous land-based direct action and cultural revitalization. It is reframing a narrative from one in which Indigenous land defense and human rights struggles vie amongst one another for external support to one in which each action exists in solidarity with and strengthens one another. It is refuting the notion that scientific progress is inherently antithetical to Indigenous knowledge paradigms and offering alternative, decolonized ways forward. In an interview with Democracy Now, Mauna protector Pua Case explained, “We are making a stand as not just Native people and not just the local community, but really a worldwide community, because there are so many similarities… there are Native people everywhere around the world standing for their mountaintops, for their waters, for their land bases, their oceans, and their lifeways. We are no different than them.” Mauna Kea is proving not only to other Indigenous frontline communities, but to all of us that another world is possible, another way of being with one another and the earth grounded in love and the wisdom of our ancestors is viable and attainable not only in our lifetimes, but in this moment. The kia’i on the Mauna are living, breathing, thriving examples of this everyday.

During my time there not only did delegations of support arrive from Aotearoa, Tahiti, and Tonga, but so did high profile visitors such as The Rock, Damien Marley and Jason Mamoa. One of these visitors was the founder of the Sacred Stone Camp at Standing Rock, LaDonna Bravebull Allard who came to support Mauna leader Pua Case- the two refer to one another as sisters. When she arrived on the Mauna, Bravebull Allard expressed that she had come to “give her sister a hug” and shared stories of how it was Case’s phone calls that got her through even the hardest days of Standing Rock. During her stay, she accepted requests to teach a session at University Pu’uhuluhulu. In which she shared that witnessing what is occurring at Mauna Kea helped her to understand her role in Standing Rock, “it was a seed we planted”, and look what has emerged, “the Mauna is bringing families together, it is bringing nations together, this Mauna is bringing the world together.”

What you can do

Further Reading

Environmental Impact Statement / TMT Alternate Site Statement / State of Emergency / Sovereign Kingdom / Annexation of Hawai’i / Pu’u Honua Pu’uhuluhulu / Pua Case on Democracy Now / Gordon and Betty Moore Divestment Petition / ACURA divestment petition / ACURA Member list / Donate Airmiles / Hawaii Community Bail Fund / HULI Paypal / KAHEA Site / Pu’uhuluhulu Instagram / Whose Land / Decolonization is for Everyone

Nikki Sanchez is a Pipil/Maya and Irish/Scottish academic, Indigenous media maker and environmental educator. Nikki holds a master’s degree in Indigenous Governance and is presently completing a PhD with a research focus on emergent Indigenous media. She presented her first TEDx presentation, entitled “Decolonization is for Everyone” this year. Nikki was the acting David Suzuki Foundation “Queen of Green” from 2016-2018 where her work centered on digital media creation to provide sustainable solutions for a healthy planet, as well as content creation to bring more racial inclusivity into the environmental movement. Her most recent media project was the VICELAND series RISE which focused on global Indigenous resurgence. RISE debuted at Sundance in February 2017 and has received global critical acclaim, recently winning the Canadian Screen Guild Award for Best Documentary series. For the past decade, Nikki has also worked as an Indigenous environmental educator, curriculum developer, and media consultant. She started and runs Decolonize Together, an independent consulting company which specializes in decolonial and equity training for businesses and institutions. She is a keynote speaker with Keynote Canada and a contributor to TEDx, Looselips and ROAR Magazine.